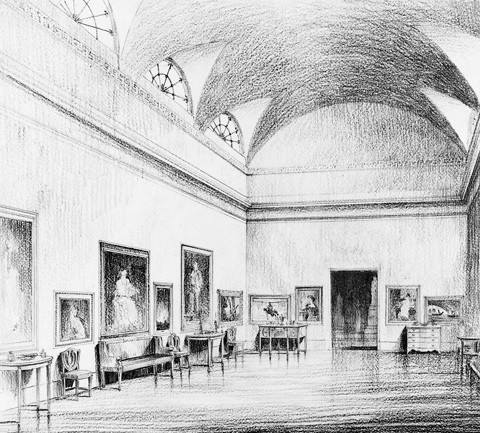

American furniture and decorative arts installation, Hudson-Fulton Celebration, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1909. (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

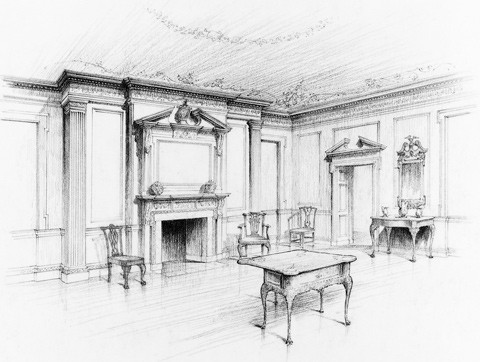

Parlor from Marmion (Prince George County, Virginia) installed in the American Wing, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, photograph ca. 1925. (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Gallery 283, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1934. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

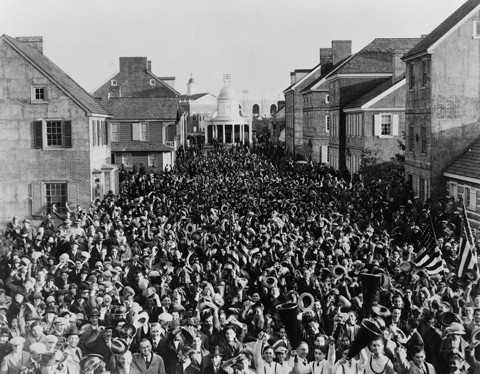

High Street, Sesquicentennial of Independence, Philadelphia, 1926. (Courtesy, Library Company of Philadelphia.)

Chippendale Room, Girl Scouts Loan Exhibition, American Art Association Galleries, New York, 1929. (Courtesy, Girl Scouts of the U.S.A.; photo, Lawrence X. Champeau.)

Plan for reinstallation of the drawing room for the Samuel Powell House (ca. 1768–1772), Philadelphia, ca. 1927. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

American furniture and decorative arts installation, Hudson-Fulton Celebration, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1909. (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

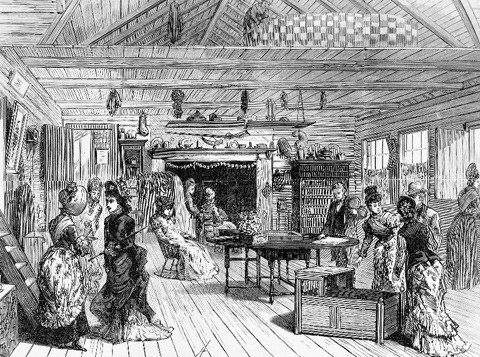

“The New England Kitchen in the Old Log Cabin,” Philadelphia Centennial, 1876. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) This image appeared in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper on June 10, 1876.

American decorative arts installation, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut, ca. 1928. (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery.)

American decorative arts gallery, Art Institute of Chicago, 2002. (Courtesy, Art Institute of Chicago.)

American Collections Gallery, Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, ca. 1999. (Courtesy, Milwaukee Art Museum.)

View of “An American Vision: Henry Francis du Pont’s Winterthur Museum,” National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., May 5–October 6, 2002. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum and the National Gallery of Art.)

American Collections Gallery, Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, ca. 1976. (Courtesy, Milwaukee Art Museum.)

Albert Sack, The Fine Points of Furniture, Early American: Good, Better, Best, Superior, Masterpiece (New York: Crown Publishers, 1993), p. 185. (Courtesy, Sack Heritage Group.)

Sideboard, American, ca. 1853. Walnut with tulip poplar and white pine; marble. H. 106", W. 69", D. 28". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; museum purchase with funds provided by Anaruth and Aron S. Gordon.)

Furniture installation from “Mining the Museum,” Maryland Historical Society, April 1992–February 1993. (Courtesy, Maryland Historical Society.)

Armchair attributed to Charles- Honore Lannuier, New York, ca. 1812. Mahogany and rosewood; brass inlay. H. 35". (Courtesy, Christie’s.)

Armchair, possibly by John Hemings, Monticello joinery, Albemarle County, Virginia, 1790–1815. Cherry; original under-upholstery and leather cover. H. 34 7/8", W. 23 1/4", D. 19 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

“Reinventing the Past,” American Collections Gallery, Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2001. (Courtesy, Milwaukee Art Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

“Classical Chaos,” American Collections Gallery, Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2001. (Courtesy, Milwaukee Art Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

“Sign Language,” American Collections Gallery, Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2001. (Courtesy, Milwaukee Art Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

“Of the Maker, By the Maker, and For the Maker,” American Collections Gallery, Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2001. (Courtesy, Milwaukee Art Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

High chest of drawers, Colchester, Connecticut, ca. 1785. Cherry with white pine. H. 82 1/2", W. 41 3/4", D. 21 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Sumpter Priddy, III.)

High chest of drawers, Boston or Salem, Massachusetts, 1755–1775. Mahogany with white pine with brass hardware. H. 85 1/2", W. 40 1/2", D. 20 3/4" "Gift of Friends of Art M1969.13". (Courtesy, Milwaukee Art Museum.)

The history of the cabinet-maker's art is the record of the unconscious struggle toward an ideal which, when finally attained, destroyed all further inspiration. This ideal persisted from one age to another, never retrograding, and each succeeding age saw it more clearly, until, at the close of the eighteenth century, it was found this limitation had been reached.

—Luke Vincent Lockwood, 1913

History has to be rewritten in every generation because, although the past does not change, the present does; each generation asks new questions of the past, and finds new areas of sympathy as it re-lives different aspects of the experiences of its predecessors.

—Sir Christopher Hill, 1972

The symposium "American Art Worlds and Material Culture," held at the Winterthur Museum in November 2001, explored the scholarly intersections of art historical, decorative arts, and material culture studies. Participants were asked to focus on "the divisions that continue to limit inquiry and to celebrate the points of conjunction that hold the potential for expansive approaches to the universe of art, artifacts, and performance." This essay, which is drawn from comments presented at the Winterthur symposium, suggests the need for greater critical consideration of American furniture scholarship and the long-standing cultural, intellectual, and institutional forces that inform its character.

While American museums of all stripes have begun to experiment with innovative ways of interpreting and presenting the past in order to engage today's audiences, the display of early American furniture - and the scholarship on which it is based - remains largely dependent on a specialized interpretive model crafted over a century ago. Rooted in the efforts of nineteenth-century museum leaders to elevate and Americanize the working class and immigrant "masses" by teaching them good taste, this orthodoxy continues to promote standards of decoration associated with the most ornate or expensive artifacts owned by prominent early Americans - a narrow reading ultimately more about the retention of cultural authority than the exploration of educational and intellectual potential. The following essay examines the origins, ideological foundations, and limitations of conventional interpretive methods and is intended to spark thoughtful discussion about the ways in which early American scholarship and display may benefit from exploring interpretive strategies that may be more relevant and engaging to today's museum visitors.[1]

The 1924 opening of the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art stands as a defining moment in the historiography of American decorative arts interpretation. The event formally codified a wide range of post-Victorian historical, aesthetic, and cultural beliefs that would become central to the evolution of subsequent American furniture scholarship. Opened fifteen years after the pioneering Hudson-Fulton Celebration (fig. 1) and the gift of the Bolles collection, which for the first time brought the "domestic arts" into the Metropolitan, the American Wing presented the arts in North America over a two century span linking specific stylistic changes with the progressive civilizing of the people with whom the art was associated. The nineteenth-century "curiosities of the past" approach to decorative arts display - with its anthropological interest in relics and its more democratic aesthetic - was replaced by installations such as the colonial Virginia parlor (fig. 2). In that vignette, artfully arranged high-style objects functioned as symbolic representations of the elevated tastes and values associated with the founding fathers and other elites. In short, the American Wing's storyline, crafted by R.T.H. Halsey and Charles Over Cornelius, celebrated the nation's historic inheritance, its craft ingenuity, and its "most beautiful" objects. In this way the Wing helped establish the self-sustaining aesthetic and ideological hierarchies that continue to inform decorative arts installations and publications today.[2]

On the most obvious level, the American Wing and other formative decorative arts installations sought to expose the public to the refined tastes and lofty principles of colonial elites (fig. 3). But as a number of scholars have noted, beneath the surface lay a more complex agenda preoccupied with cultural literacy, ethnic identity, class distinctions, and changing ideas about race and gender. Early twentieth-century museum professionals and social and political leaders relied on the objects and apocryphal histories associated with the nation's past as a means to "civilize" the working classes and school immigrants in the ideals of American culture. Colonial era antiques were, according to Elizabeth Stillinger, understood as "appropriate vehicles for informing foreigners and less enlightened natives as to American traditions and values" and as "educational tools" that could encourage assimilation.[3]

Museum catalogues and auctions of several important collections also played a crucial role in promoting the evolution of this more select, elitist canon of American decorative arts objects. So too did the emergence of new publications aimed at the general public. Homer Eaton Keyes, the first editor of The Magazine Antiques, envisioned a journal devoted to "recording and interpreting those significant souvenirs of man's creative genius" and that could serve as the foundation upon which to build a "superstructure of steadily increasing beauty, power, and usefulness." Antiques provided a forum that effectively supported the mutually beneficial scholarly and financial agendas of influential collectors, dealers, and curators and reinforced the same lofty themes that underlay the formative decorative arts displays of the 1920s.[4]

Other pivotal events included the 1926 Philadelphia Sesquicentennial Fair, which initiated visitors to the colonial revival ethos at its most potent. The aptly named "High Street" exhibition celebrated the nation's political and cultural legacy and glorified the beauty, productivity, and domestic virtues embodied in early American shops and homes (fig. 4). As the authors of the 1929 Girl Scouts Loan Exhibition catalogue explained, the objects owned by early Americans revealed them as a people who were both "cultured and courageous," capable of creating an "atmosphere of comfort, of beauty, and of culture" in even the most humble of circumstances (fig. 5).[5]

The Girl Scouts Loan Exhibition and other shows and publications of the era helped codify what social historian Steven Conn refers to as an "emerging twentieth-century fantasy of what life was like in the eighteenth century" - a fantasy rooted equally in nostalgia and didacticism. Conn recounts the story of the opening of High Street, where a hostess at the Stephen Girard House told a reporter that the purpose of the exhibition was "to reveal the fine heritage of beauty and dignity in ordinary everyday life which our ancestors have passed on to us. It proves that our beginnings were not chaotic, lawless, cheap or tawdry, but essentially noble and dignified." Early decorative arts displays and publications created a vision of the past that offered the so-called cultured classes symbolic refuge from the intrusions of mass culture in all its vulgarity. At the same time, they provided immigrant and working classes with a model of the accessories and associated ideals that could help them achieve middle-class status and become literate in core American values.[6]

A similar agenda informed pioneering decorative arts installations at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (fig. 6), the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and Colonial Williamsburg - institutions whose ideological orientation echoed that of the celebrated 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, with its pointed division between the Midway Plaisance and the fittingly named White City. The former venue was exciting, crowded, and meant to entertain the masses; the latter sought to expose them to the most ennobling art and ideals of western culture. As historian Lawrence Levine suggests, the White City encouraged and helped maintain the division between "highbrow" and "lowbrow." American art museums, concert halls, and department stores likewise functioned to make public audiences more cognizant of the divide between high and low culture and, simultaneously, to render museum visitors more docile. Art gradually became a one-way process, with the artist and the curator giving and the museum audience receiving.[7]

One of the main messages early twentieth-century museum leaders promoted was the idea that America's artistic traditions, most fully expressed in the material culture of the elite, had descended directly from England. "To study artistic development in its relation to nationality," explained Charles Over Cornelius, "the opportunity for expression of personal taste must be sought in the homes of the rich or well-to-do," the segment of society most likely to display the "sophistication of taste" characteristic of a nation's best and most refined art, including furniture and other craft traditions. As the authors of the catalogue to the Hudson-Fulton Celebration explained, the "history of American furniture is comprehended in the history of English furniture," while the contributions of "Dutch, French, Spanish, and Swedish" and other ethnic groups were, at best, negligible. By the start of the twentieth century, scholars and curators of American decorative arts had forged an aesthetic whose ideological underpinnings were based on a yearning for the cultural stability and ethnic homogeneity of an imagined past, where Anglo-American craftsmen transformed utilitarian objects into art forms that were used by and expressed the values of an enlightened and educated clientele (fig. 7).[8]

As ideas about ethnicity and race began to change in the decades that followed, American decorative arts scholars developed a more nuanced understanding of the role that non-English immigrants played in contributing to America's artistic heritage. In Early American Furniture Makers (1930), Thomas Ormsbee described a colonial America whose relatively diverse craft traditions reflected the contributions not just of the English but of the "Scotch, Welsh, Irish, Hollander, and French Huguenots" along with a "few Germans, Swiss, Swedes, and Spanish and Portugese Jews," whose presence added "cosmopolitan variety." Underlying the seemingly more democratic characterization of colonial America, however, was an increasingly polarized definition of race, as the "alien" ethnic identity of certain groups - such as Germans, Irish, and, to a lesser extent, Jews - was gradually subsumed under a new racial identity defined as "white." This more expansive definition of Anglo-American identity and tradition coincided with and depended upon the deliberate erasure of blackness in American decorative arts scholarship and remains evident today in the conspicuous placement of African-American, Native American, and Latino craft traditions in the categories of "folk" and "outsider" art.[9]

The emerging construct of an American decorative arts tradition based in the primacy of white, Anglo-American culture depended not just on the erasure of the non-white but on the marginalization of the female as well. As historian Patricia West has documented, the rise of large metropolitan museums in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was led by a class of professional men who implemented a new aesthetic based on a notion of connoisseurship defined in opposition to the "ladies auxiliary" aesthetic at work in the largely female-dominated house museums, fairs, and historic monuments (fig. 8). Newer, more rigidly ordered, and masculinized displays (fig. 9) promoted a "slick, professional exhibitry" that reinforced "a growing element of elitism and connoisseurship" in museums generally and resulted in diminished leadership roles for women.[10]

An emphasis on the implicitly masculine virtues of early American furniture was also exemplified in written histories through the transformation of the cabinetmaker into an iconic figure. "Where formerly the joiner had built not only furniture but also wainscoting and the great wood roofs of halls and rooms," noted Charles Over Cornelius in 1930, "his place was taken by the man who made furniture only." The result of this transformation was the emergence of a figure who was not only an artisan but an artist as well. The colonial cabinetmaker was increasingly depicted as a heroic figure who, like the founding fathers, embodied such masculine ideals as individualism, independence, self-determination, and creative ingenuity. In 1928, Edward Stratton Holloway wrote that early American furniture "was made not by machines but by men: and man when he works individually is invariably possessed by the itch to create, to develop his own idea, to express himself, and not literally to copy." Reflecting antimodernist concerns regarding the emasculating threat posed by the machine age, twentieth-century furniture scholars envisioned the cabinetmaker as a figure who embodied the manly "vigour" that lay at the heart of America's national character and its craft traditions.[11]

Today, too many displays of early American furniture continue to rely on interpretive approaches that were born out of the nineteenth century and shaped by the era's particular cultural concerns regarding gender, race, ethnicity, and class. Pioneering decorative arts exhibitions such as the American Wing can and should be celebrated for their contributions to preserving and understanding early American art and history. But there remains a pressing need for today's curators to recognize what cultural historian Paul Dimaggio terms "the cognitive and institutional barriers" that stifle the consideration of alternative modes of interpretation more attuned to contemporary sensibilities. In an essay on museum ethics, David Carr contends that the central failing in many institutions is their tendency to leave the visitor feeling powerless and disengaged. Too often decorative arts displays do just that by relying on a time-worn presentation of early American material culture that is communicated to the public via jargon-filled labels and presumed aesthetic hierarchies. Generally only the most discerning or highly trained viewer can distinguish one exhibition of early American chairs, tables, and chests from another (figs. 10-12). One promising strategy involves greater critical consideration of the exhibits themselves, "which may be artifacts of a higher order and which require important and serious analysis." This process necessarily involves a transdisciplinary approach built on theoretical advancements in other areas of cultural studies.[12]

Early American furniture scholarship and display could benefit from incorporating advanced interpretive models in fields such as history and art history. Literary studies, which like the study of decorative arts emerged as a formal academic discipline in the nineteenth century, offer another promising source. The intellectual and aesthetic preoccupations of both fields were shaped by the same early twentieth-century cultural anxieties, which were largely fueled by industrialization, urbanization, the rise of mass culture, the growing influence of the market, and other sweeping changes associated with modernization. As each discipline evolved into a profession practiced within institutional settings, literary and decorative arts scholars embraced formal analysis based on subjective evaluation and presumed aesthetic hierarchies. This interpretive strategy encouraged the development of a canon of objects and texts grounded in Anglo-American culture and largely produced by educated, affluent, native-born white men.

Literary and decorative arts scholarship continued to follow parallel paths until the mid-twentieth century, when female and minority scholars of literature, who had previously been underrepresented in the field, began to expand the study of what had traditionally been considered non-canonical works. Newer, student-centered pedagogies emerged that encouraged the teaching and interpretation of texts more broadly reflective of the diversity of American society and the growing diversity of its universities. Scholars gradually abandoned formalist aesthetic hierarchies in favor of a greater consideration of a wider range of interpretive strategies. The result of these changes was not, as some feared, the widespread rejection of such authors as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, or William Faulkner, but the emergence of spirited and less formulaic scholarship on canonical writers generally. At the same time, the newer interpretive approaches helped uncover the literary, cultural, and historical richness in the work of previously neglected authors such as Frederick Douglass, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Zora Neale Hurston.[13]

The study and teaching of American history experienced a similar evolution, as the "great men" and "great events" paradigm was expanded to include the histories of women, minority and non-western cultures, and non-elites. Historians have largely accepted what historian Gary Nash terms the "pragmatic revolt in American history" and, like literary scholars, have recognized the ways in which embracing diversity, utilizing multiple interpretive strategies, and accepting the subjective nature of interpretation itself can only enrich scholarship in their field.[14]

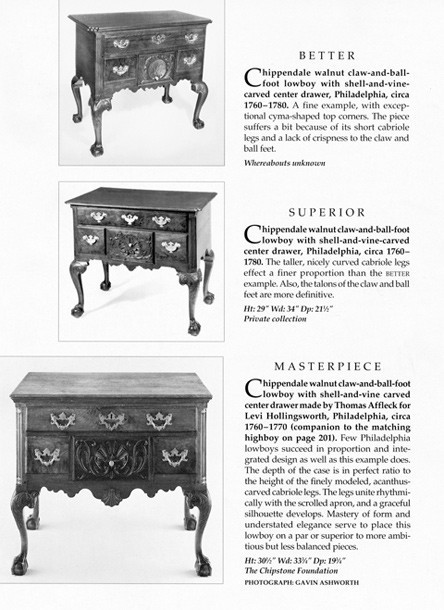

By contrast, scholars of American furniture have yet to formally acknowledge the existence of a canon, let alone engage in critical discourse about its origins, contents, or functions. Decorative arts historian Edward S. Cooke argues that the canonization of a select group of American furniture makers, such as Benjamin Randolph and Duncan Phyfe, "permits little understanding of the individual's relation to other furniture makers or to his society." The canonization of specific regional designs and forms - Newport blockfront furniture, Boston bombé case pieces, and Philadelphia high chests, to cite just a few - similarly limits understanding of interrelationships among objects and results in a narrow interpretive model in which the discrete object is held above and apart from the cultural and historical contexts in which it was produced (fig. 13).[15]

The quantity of publications and symposia in the field each year gives the impression that early American furniture scholarship is robust, but these forums often fail to reflect or incorporate creative theoretical models that have advanced scholarship in other fields within the humanities. Certainly the best known new methodology in the area of artifact interpretation is material culture studies, which promotes the inclusion of a wide range of scholarship, encourages cooperation between academic and museum-based scholars, and allows for the merging of inductive and deductive modes of reasoning. Despite the potential of this innovative and inclusive approach, too many museum installations rely on the same interpretive strategies that informed the pioneering decorative arts displays and that are exemplified in the "good-better-best" formula (fig. 14) first articulated half a century ago in dealer Albert Sack's Fine Points of Furniture, Early American. In 1985, Perspectives on American Furniture, a published collection of papers presented at a Winterthur Museum conference, proclaimed a generational shift in furniture studies. The new approach promised to incorporate a specific "emphasis on furniture as a cultural index to human behavior and on the wide-ranging approach that takes in stride all manner of furniture regardless of aesthetic merit." While articles in American Furniture and other publications over the past decade suggest a wide range of topics, progress has been relatively slow. As Henry Glassie and others have noted, scholars in both museums and the academy have failed to fulfill material culture's potential as "a new transdisciplinary practice, at once scientific and humanistic." Decorative arts displays and publications continue to devote approximately ninety percent of their interpretation to "material" and only ten percent to "culture," which becomes all the more significant in light of the fact that more than ninety percent of the objects shown were owned by less than ten percent of early Americans.[16]

To be sure, contemporary curators bring to their analyses unprecedented object literacy, which has resulted in a better understanding of regional furniture making and individual shop traditions. But museum displays in particular have generally neglected to build on the work of innovative scholars and curators who have explored alternative modes of interpretation that forward, challenge, or even invert basic decorative arts assumptions. Laurel Thatcher Ulrich and Amanda Carson Banks have, for example, used theory on gender and material culture to develop new readings of familiar objects like the Hannah Barnard cupboard and to shed light on birth chairs and other previously neglected furniture forms. Museum installations could benefit from incorporating these and other innovative approaches, including decorative arts scholar Kenneth Ames' study of Victorian furniture titled Death in the Dining Room. Ames demonstrates the ways in which both the design and the thematic complexity of Victorian furniture reflect the larger social, moral, and economic complexities of late nineteenth-century America. Ambiguity and contradiction, Ames argues, lie at the heart of the material culture of the intensely materialistic Victorians and necessitate an artifactual interpretation that is "appropriately and consciously broad and general." For instance, he contextualizes the immense and ornate sideboards of the era (fig. 15) within the "iconography of dining." These monumental forms - covered with carved depictions of hunting paraphernalia, dead animals, and symbolic hunters - literally and figuratively brought death into Victorian dining rooms in a manner that today seems disturbingly graphic and violent. Sideboards functioned as the ritualized products of an "undeniably romantic and self-conscious age" whose intensely realistic imagery suggests an acknowledgment of "the earthly origins" of food and "the relationship of humankind to the rest of the animal kingdom." Ames' interpretive model is highly adaptable and offers access to cultural concepts that conventional, more deductive forms of artifact analysis would necessarily overlook.[17]

Equally creative are the museum installations of exhibit curator and designer Fred Wilson, who deliberately subverts traditional decorative arts standards by taking the most celebrated museum pieces and juxtaposing or positioning them in unexpected ways. By focusing on the deeply entrenched cultural imbalances that influence much decorative arts scholarship, he challenges both the canon and the canonizers. "Mining the Museum," a 1992 exhibition at the Maryland Historical Society, featured expensive silver teapots and wrought-iron slave shackles side-by-side in a display of early American metals. Similarly he arranged high style chairs - seating associated with wealthy, educated elites - around a whipping post that he had "mined" from the museum's own storerooms (fig. 16). As Wilson explains, such juxtapositions "disrupt the standard way of looking at museums" by directly confronting the fiction that they are objective or removed from specific political, historical, or aesthetic points of view. Wilson's installation - what he terms an "intervention" - exposed a shameful historical practice. At the same time, it challenged the very character of the museum and, as Hilde S. Hein elaborates, in effect charged the institution "with a deception, witting or unwitting, that belies its dedication to authenticity."[18]

The exploration of cultural diversity and multiple scholarly perspectives - what Lawrence Levine calls the "opening of the American mind" - has become increasingly common throughout many American institutions, including schools and universities, government organizations, public museums, and libraries. Decorative arts scholarship and, in particular, the museum displays that draw from it can only benefit from a more widespread incorporation of interpretive possibilities that offer new ways of looking at old things. The conventional decorative arts paradigm, for example, would justify the inclusion of a French-influenced New York neoclassical armchair (fig. 17) in the canon of furniture on the basis of aesthetics alone, just as it would justify the exclusion of a Virginia, French style armchair on the same grounds (fig. 18). Indeed, only the fact that the latter chair was made for Thomas Jefferson might allow for a special exemption. But a more nuanced and ultimately more fruitful interpretive approach to these two chairs would also consider other forces that shaped their creation. The Virginia chair was made in the slave joinery shop at Monticello where Jefferson obsessively managed craft production by controlling the design of furniture produced there and by altering the design of furniture imported from other places. Jefferson had little use for the highly sculpted or carved colonial forms so valued by today's curators, collectors, and dealers. Instead, like many other affluent southerners, he preferred what was commonly known as "neat and plain" style, the only difference being that he favored furniture that spoke with a French rather than an English accent. Like so many other pieces at Monticello, the chair reflects Jefferson's regionally influenced and somewhat idiosyncratic aesthetic sensibilities and speaks as well to issues concerning race, slavery, and the canonization process. An interpretive approach more fully grounded in contemporary cultural studies might, for example, explore the relationship between the non-canonical status of this chair and its maker - most likely John Hemings, who as a slave could never embody the qualities of self-determination, independence, individualism and artistic freedom associated with the iconic figure of the American craftsman. Viewed through the lens of traditional decorative arts interpretation, the New York chair stands as a fine example of sophisticated, early American design. But viewed from a transdisciplinary perspective more fully grounded in cultural studies, the Jefferson chair arguably tells a more complex and, for many modern viewers, a more meaningful and distinctly American story.[19]

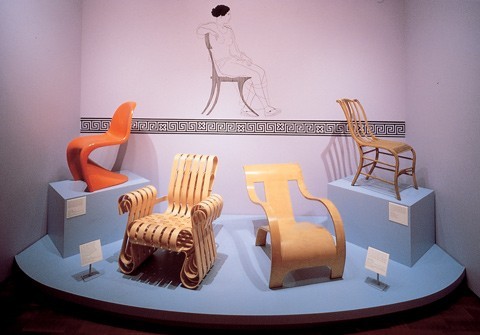

These kinds of interdisciplinary, culturally grounded modes of artifact analysis - as well as an interest in the novel methods of interpretation and presentation found in other kinds of museums - are explored in the recent reinstallation of the decorative arts galleries at the Milwaukee Art Museum, which merges the museum's collection with those of the Chipstone Foundation and the Layton Art Collection. Created by a team of curators with diverse scholarly interests, the Milwaukee galleries largely abandon the specialized categories of art historical difference that are the essence of conventional decorative arts interpretation - the time-honored strategy of teaching the distinctive stylistic, structural, and regional features that distinguish one piece or group of early American furniture from another. Instead, the aim is to more broadly consider ideological and stylistic continuities, an interpretive strategy that characterizes much of the newer scholarship in other fields. The value of an interpretive method grounded in "continuities rather than ruptures," argues literary critic Jane Tompkins, lies in the potential it offers for "tapping into a storehouse of commonly held assumptions" not typically found in the more exceptional or canonical works. By employing an interpretive method that looks for value not in difference but in a text or object's "embrace of what is most widely shared," it becomes possible to find much of scholarly interest in the non-canonical as well as to find new ways of understanding the canonical (fig. 19).[20]

The Milwaukee exhibitions ask new questions of the canonical objects that comprise the majority of the three collections, an approach that in turn reveals alternative interpretive strategies. The focus on cultural and stylistic continuities, for example, shows how a "William and Mary" kast, a "Victorian" parlor chair, and a "Chippendale" desk-and-bookcase all share a fundamental allegiance to the precepts of classical order and geometry, or how a Philadelphia rococo side chair and Eero Saarinan's contemporary "Womb Chair" both are linked to decidedly more chaotic themes found in classical literature and art (fig. 20). This interpretive process also leads to an expanded understanding of the complex symbolic interactions between people and artifacts and the ways in which, for instance, signatures on furniture may simultaneously reflect and shape the identities of owners and makers alike (fig. 21).

In considering other issues, such as to what extent early American furniture was genuinely "American," the curatorial team drew from the work of a range of scholars to look beyond the traditional decorative arts aesthetic. Edward S. Cooke's methodological analysis of chair making in rural New England, particularly his emphasis on the distinctive web of relations "that inseparably linked the furniture maker's craft decisions to the unique social and economic contexts in which they were made," offered a useful interpretive model. For example, the earliest furniture makers, including immigrant joiners such as Ralph Mason and Henry Messinger, were able to replicate familiar British furniture designs for use in relatively insulated cultural settings. Later American furniture makers - including members of the famed Townsend and Goddard families of Newport - faced ever more complex social economies in which uneven access to cosmopolitan fashion systems and varying degrees of artifact and artisan movement led to the increased diversity of American furniture designs (fig. 22). According to traditional decorative arts standards, a Colchester high chest (fig. 23) is eccentric, "rural," and stylistically derivative of forms produced in urban centers such as Boston or Salem (fig. 24). Understood as the product of a specific social economy, however, the piece emerges as a distinctively American object whose meaning and form were shaped by a "web of relations and activities" unique to its locale. Milwaukee's decorative arts galleries seek to move beyond a presentation of the evolution of form, style, and construction - as is the decorative arts norm - and set aside the rigid cultural hierarchies and specialized art historical jargon found in so many museum displays. Rather, these spaces explore alternative interpretive possibilities that may more effectively engage contemporary museum visitors, especially those who may arrive thinking that, beyond stylistic evolution, "a chair is a chair is a chair."[21]

Ultimately, museums that exhibit and, in the process, interpret American decorative arts need to more critically assess traditional modes of artifact analysis and to draw more directly from scholarship in other areas of cultural studies and exhibition innovations in other museums. "Themed" displays, which invariably claim to offer a new perspective, need to do more than just re-order or re-describe conventional interpretive paradigms. In a process literary critic Henry Louis Gates, Jr., terms the "reconstruction of instruction," the American furniture canon - like the literary canon - must either be expanded, dismissed altogether, or thoughtfully reconfigured into entirely new canons that reflect a perspective markedly different from the received tradition. Just as the pioneering museum displays were distinctive expressions of late nineteenth-century America, contemporary decorative arts installations need to reflect the issues and concerns relevant to early twenty-first century America.[22]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Glenn Adamson, Luke Beckerdite, Edward S. Cooke, and Gerald W. R. Ward for their critical comments on this work and Robert F. Trent for his research on the formative American furniture histories and installations.

Scholars and curators of decorative arts have long debated the value of aesthetic evaluation and cultural hierarchies. Michael J. Ettema, "Forum—History, Nostalgia, and American Furniture," Winterthur Portfolio 17, nos. 2/3 (summer/fall 1982): 135—44. Ettema argued that the antiquarian approach should be abandoned in favor of interpretive methods that placed history and culture, not objects and aesthetics, at the center. The essay provoked a wide range of responses. Some scholars acknowledged Ettema's conclusion that the field was not living up to its potential, some voiced concerns that he was not offering new directions that were in accord with the traditional mission of art museums, whereas others rejected his argument that interpretive strategies based in aesthetics were necessarily more limited than methods grounded in cultural history (see Winterthur Portfolio 17, no. 4 [winter 1982]: 259—68, and Winterthur Portfolio 18, no. 1 [spring 1983]: 80—90.) Wendy Kaplan, "R. T. H. Halsey: An Ideology of Collecting American Decorative Arts," Winterthur Portfolio 17, no. 1 (spring 1982): 43—53. For a discussion of the divide between curators and scholars, see Jules D. Prown, "Can the Farmer and the Cowman Still Be Friends" in Learning From Things: Method and Theory of Material Culture Studies, edited by W. David Kingery (Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1996), pp.19—27.

R. T. H. Halsey and Charles O. Cornelius, A Handbook of the American Wing, 4th ed. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1928), p. xv. Notable examples of earlier scholarship, much of it well researched, include Irving Whitehall Lyon, The Colonial Furniture of New England (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1891); Esther Singleton, The Furniture of our Forefathers (New York: Doubleday, Page and Co., 1908); Luke Vincent Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1913); and Frances Clary Morse, Furniture of the Olden Time (New York: MacMillan Co., 1917). For a thoughtful overview of early decorative arts installations, see Elizabeth Stillinger, The Antiquers: The Lives and Careers, The Deals, The Finds, The Collections of the Men and Women Who Were Responsible for the Changing Taste in American Antiques, 1850—1930 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980).

Stillinger, The Antiquers, p. 124.

"The Editor's Attic," Antiques 16, no. 2 (August 1929): 101.

Girl Scouts Loan Exhibition of Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Century Furniture and Glass (New York: Girl Scouts, Inc., 1929), preface.

Quoted in Stephen Conn, Museums and American Intellectual Life, 1876—1926 (Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press, 1998), p. 241.

See Lawrence Levine, Highbrow/Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1988), pp. 185—208. Neil Harris, "Museum, Merchandising, and Popular Taste: The Struggle for Influence," in Material Culture and the Study of American Life, edited by Ian M. G. Quimby (Winterthur, Del.: Winterthur Museum, 1978), p. 142.

Charles Over Cornelius, Early American Furniture (New York: Century Co., 1926), p. 16. Henry Watson West and Florence N. Levy, Catalogue of an Exhibition of American Paintings, Furniture, Silver and Other Objects of Art (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1909), p. 29.

Thomas Hamilton Ormsbee, Early American Furniture Makers: A Social and Biographical Study (New York: Tudor Publishing Co., 1930), pp. 37—38. On the formation of white racial identity and its dependence on the marginalization of the non-white, see Matthew Frye Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1998).

Patricia West, Domesticating History: The Political Origins of America's House Museums (Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1999), pp. 48—50. On the influence of gender in twentieth-century decorative arts studies, see Catherine L. Whalen, "American Decorative Arts Studies at Yale and Winterthur: The Politics of Gender, Gentility, and Academia," Decorative Arts 9, no.1 (fall/winter 2001—2002): 108—44. The emergence of a more masculinized period room aesthetic and an increasing emphasis on the manliness of American craft traditions were associated, as West argues, with the diminished status of female museum professionals throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Yet women, including Helen Comstock and Alice Winchester, played prominent roles as the authors of popular histories and publications of American furniture. Future scholarship on the gender politics of early decorative arts might benefit by examining the connections between the relative prominence of women as authors of decorative arts publications and female dominance of the literary marketplace more generally.

Cornelius, Early American Furniture, p. 105. On the "elevation of the craftsman" and the link to the founding fathers, see Kaplan, "R. T. H. Halsey," p. 51. Edmund Stratton Holloway, American Furniture and Decoration Colonial and Federal (Philadelphia, Pa.: J. B. Lippincott, 1928), pp. 8—9.

Paul Dimaggio, "Cultural Boundaries and Structural Change: The Extension of the High Culture Model to Theater, Opera, and the Dance, 1900—1940," in Cultivating Differences: Symbolic Boundaries and the Making of Inequality, edited by Michèle Lamont and Marcel Fournier (Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press, 1992), p. 47. David Carr, "Balancing Act: Ethics, Mission, and the Public Trust," in Museum News 80, no. 5 (September/October 2001): 29—31. Harold K. Skramstad, Jr., "Interpreting Material Culture: A View from the Other Side of the Glass," in Quimby, ed., Material Culture and the Study of American Life, p. 181.

For an overview and analysis of the key developments and issues in twentieth-century literary studies, see Paul Lauter, Canons and Contexts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991).

Gary B. Nash, Charlotte Crabtree, and Ross E. Dunn, History on Trial: Culture Wars and The Teaching of the Past (New York: Vintage Books, 1997), p. 40. As Robert F. Trent has suggested, furniture scholarship could be enriched by incorporating post-colonial theory that considers American art and culture as the products of a broader, international colonial context (correspondence with the authors, June 10, 2002).

Edward S. Cooke, "Study from the Perspective of the Maker," in Perspectives on American Furniture, edited by Gerald W. R. Ward (Newark: University of Delaware for the Winterthur Museum, 1985), pp. 115—16.

Albert Sack, Fine Points of Furniture, Early American (New York: Crown Publishers, 1950). This formula has since been augmented to include "superior" and "masterpiece." Scholarship in the field could benefit from greater consideration of the role played by the antiques market in the emergence of the American decorative arts canon. A number of the most influential dealers were first or second generation immigrants who sold American antiques to a growing market composed of clients hoping to become part of the cultured classes. Analysis of the emerging market in American antiques might, for example, incorporate recent scholarship on the early film industry, which was in many ways influenced by similar cultural dynamics and desires, or pay closer attention to the broader relationship between the market and the preoccupation in the culture at large with issues related to class, ethnicity, and assimilation. Henry Glassie, Material Culture (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999), pp. 1—3. Jules D. Prown, "Can the Farmer and the Cowman Still Be Friends?" p. 20. Glassie, Material Culture, pp. 1—3.

Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, "Furniture as Social History: Gender, Property, and Memory in the Decorative Arts," in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N. H.: University of New England Press for the Chipstone Foundation, 1995), pp. 39—69; Amanda Carson Banks, Birth Chairs, Midwives, and Medicine (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1999). Kenneth L. Ames, Death in the Dining Room (Philadelphia, Pa.: Temple University Press, 1992), pp. 2—6 and passim.

Steven C. Dubin, Displays of Power: Controversy in the American Museum from the Enola Gay to Sensation (New York: New York University Press, 1999), p. 14. Hilde S. Hein, The Museum in Transition: A Philosophical Perspective (Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2000), p. 105. One particularly innovative example of re-thinking museum exhibits is the Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles, a fascinating and, at times, surrealistic place that "deploys all the traditional signs of a museum's institutional authority—meticulous presentation, exhaustive captions, hushed lighting, and state-of-the-art armature—all to subvert the notions of the authoritative as it applies not only to itself but to any museum" (Lawrence Weschler, Mr. Wilson's Cabinet of Wonder: Pronged Ants, Horned Humans, Mice on Toast, and Other Marvels of Jurassic Technology [New York: Vintage Books, 1995], p. 40).

Lawrence Levine, The Opening of the American Mind (Boston, Mass.: Beacon Press, 1996). This book was written as a direct response to the politically and culturally conservative interpretation in Allan Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987). Ronald L. Hurst and Jonathan Prown, Southern Furniture, 1680—1830: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1997), pp.142—46. The widely held belief in the non-canonical status of southern furniture makers from the American furniture canon is epitomized in Carl Bridenbaugh, The Colonial Craftsman (New York: New York University Press, 1950).

Jane Tompkins, Sensational Designs: The Cultural Work of American Fiction, 1790—1860 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), p. xvi.

Edward S. Cooke, Jr., "The Social Economy of the Preindustrial Joiner in Western Connecticut, 1750—1800," in Beckerdite, ed., American Furniture (1995), pp. 113—14; and Edward S. Cooke, Jr., Making Furniture in Preindustrial America: The Social Economy of Newtown and Woodbury, Connecticut (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), pp. 3—12.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Loose Canons: Notes on the Culture Wars (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), p. 9; Lauter, Canons and Contexts, pp. 256—70; and Lillian Robinson, "Canons to the Left of Them," in In The Canon's Mouth (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997), pp. 120—V23.