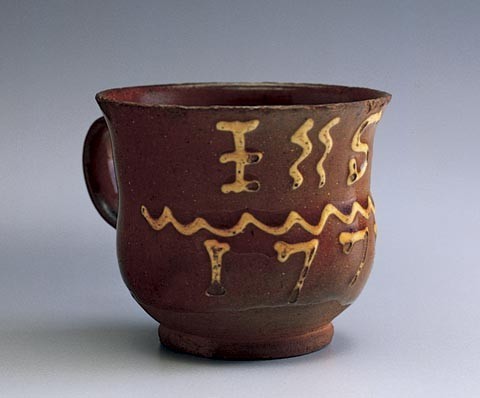

Three-handled cup, possibly Staffordshire, 1640–1660. Black lead-glazed earthenware. H. 3 1/2". (All objects from the Troy D. Chappell Collection; photos, Gavin Ashworth.) This multihandled cup is a remnant of medieval communal drinking vessels made by localized potteries throughout England. Fragments of similar cups have been found on early-seventeenth-century settlements in the Chesapeake region.

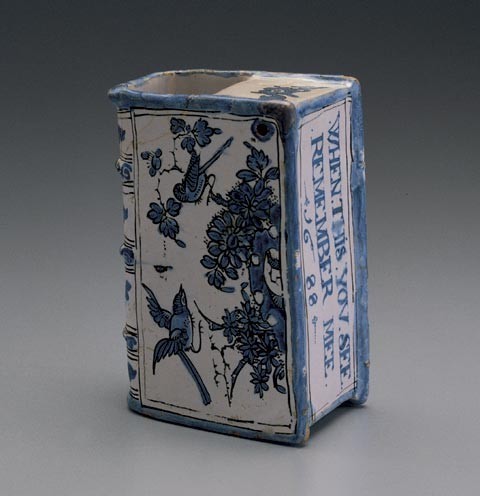

Hand warmer, probably London, dated 1688. Delftware (tin-glazed earthenware). H. 4 7/8". Molded in the style of a book, this object was thought to hold hot water. Inscribed “when this yov see / remember mee / 1688.”

Dish, probably London, ca. 1690. Delftware. D. 8 3/4". This press-molded dish is of a type made in England and on the Continent. No foot ring is present, often an English feature.

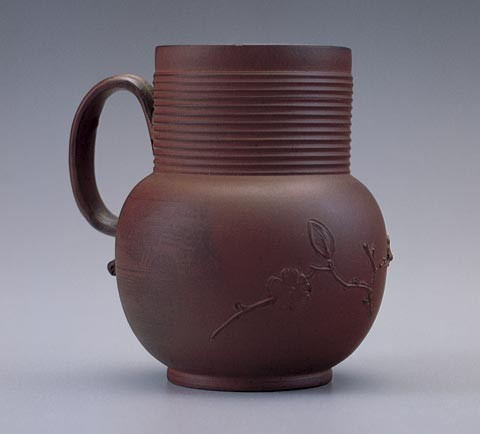

Mug, attributed to David and John Philip Elers, probably Staffordshire, ca. 1695. Unglazed red stoneware. H. 3 5/8". The mug was slip cast and subsequently turned on a lathe. The branch and leaf sprigs were mold applied.

Cup, probably Staffordshire, 1690–1700. Slipware, combed or feathered. H. 4". The potter added the unusual “S” pattern in the decoration.

Dish or charger, probably London, 1702–1714. Delftware. D. 14". Inscribed “A R” for Anna Regina or Queen Anne. The back of this charger has a lead glaze over the tin glaze and a low pedestal foot.

Plate, London, 1740–1760. Delftware. D. 8 5/8". (Ex-collection: Dennis J. Cockell.)

Mug, Staffordshire, 1720–1730. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 3 1/8". Stoneware clay covered in a white slip and iron oxide applied to rim.

Sugar basin and cover, probably Bristol or Brislington, 1720–1730. Delftware. H. 6".

Figure of bird, Staffordshire, 1725–1730. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5 1/8". Slip and incised decoration. (Ex-collection: Major Cyril Earle.)

Cream jug, Staffordshire, ca. 1740.

Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 3 1/8". Mold-applied blue clay sprigs and tripod-footed base after a silver shape. (Ex-collections: Major Cyril Earle, Mrs. Catherine Collins.)

Mug, attributed to Samuel Bell, Staffordshire (Newcastle-under-Lyme), ca. 1740. Agateware. H. 4 1/2". Thrown on the wheel, this mug is composed of different-colored earthenware clays.

Dish, Bristol, ca. 1740. Delftware. D. 12 7/8". Decorated in a stamped circle technique. This large dish has a trimmed foot ring.

Plate, Bristol, 1740–1760. Delftware. D. 9".

Plate, London, 1745–1750. Delftware. D. 9". The card motifs are painted in the reserve area of a dense cobalt “powder” ground.

Jug, Staffordshire, 1750–1765. Slipware. H. 5 1/2". The checkerboard slip decoration is highlighted with cobalt blue.

Teapot, Staffordshire, 1750–1760. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 4 1/8". (Ex-collection: Mrs. Eugenia Cary Stoller.)

Bowl, Staffordshire, 1750–1760. Cream-colored earthenware. D. 4 1/2". Mold-applied sprig decoration and underglaze oxide colors. (Ex-collection: Sir Victor and Lady Gollancz.)

Sauceboat, Staffordshire, 1750–1760. Salt-glazed stoneware. L. 6 5/8". After a silver shape, this sauceboat was slip cast and highlighted with dabbed cobalt blue.

Teapot, Staffordshire, 1755–1760. Colored-body earthenware. H. 4 3/4"

Teapot, Staffordshire, 1755–1765. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 4 7/8". The polychrome decoration was enameled over the salt glaze and refired to set the colors.

Teapot, Staffordshire, 1755–1765. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 3 7/8". (Ex-collection: Mrs. Russell S. Carter.)

Chimney vase, probably Liverpool, ca. 1755. Delftware. H. 5 3/8". This type of decoration is generally referred to as the Fazackerly colors.

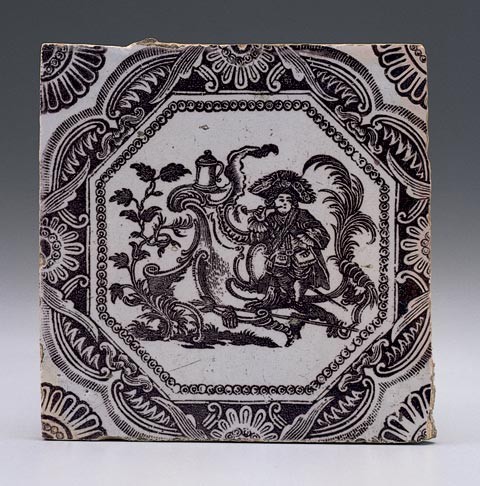

Wall tile, attributed to John Sadler printshop, Liverpool, 1756–1757. Delftware. W. 5". Woodblock print after Nilson of Augsburg.

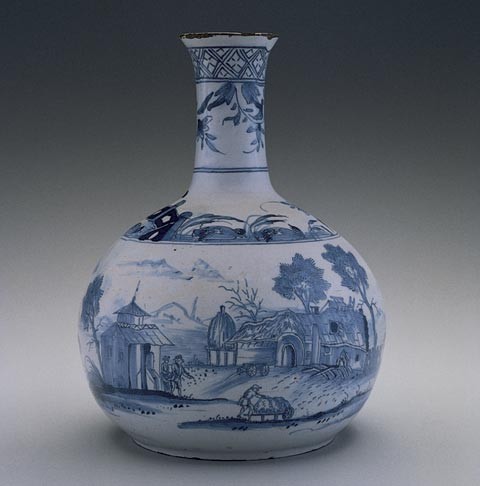

Water bottle, probably Liverpool, ca. 1760. Delftware. H. 8 1/4". The painted scenes include both Western and chinoiserie images.

Teapot, probably Staffordshire, ca. 1760. Cream-colored earthenware. H. 4 3/4". A very unusual teapot with mold-applied brown clay and underglaze oxide colors.

Monkey figure, Staffordshire, ca. 1760. Cream-colored earthenware. H. 41/2". This press-molded figure is highlighted in underglaze oxide colors.

Plate, Staffordshire, ca. 1760. Cream-colored earthenware. D. 9 1/2". A very unusual press-molded plate with underglaze oxide colors.

Plate, Liverpool, ca. 1760–1765. Delftware. D. 8 5/8". (Ex-collection: Frederic H. Garner, Moorwood Collection.)

Plate, possibly Liverpool or Staffordshire, 1760–1765. Salt-glazed stoneware. D. 8 1/2". Three-color transfer print of Aesop’s The Fox and the Goat. (Ex-collection: Joseph E. Lowy.)

Teapot, Staffordshire, ca. 1765. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 3 3/4". The colors on this pot appear to have been added over the saltglaze and refired with a lead glaze.

Milk jug, Staffordshire, ca. 1765. Cream-colored earthenware. H. 3 1/2". This press-molded pineapple jug is highlighted with underglaze oxide colors. Similar fragments have been excavated in Williamsburg, Virginia.

Wall tile, attributed to John Sadler and/or Guy Green printshop, Liverpool, 1764–1775. Delftware. W. 5 1/8". Transfer printed after an engraving depicting a Turkish merchant. (Ex-collection: Louis L. Lipski.)

Teapot, attributed to William Greatbatch, Staffordshire (Fenton), 1770–1782. Creamware. H. 5 1/2". Gilding and enamel decoration of Cybele and Bacchus as satyrs.

Dish, probably Staffordshire, 1770–1775. Creamware. L. 9 3/8 ". Transfer-print decoration of Blindman’s Buff. The rim border elements are very unusual as each is nonrepeating. Smooth bottom.

Plate, London, dated 1776. Delftware. D. 9". Inscribed “stephen dell” on front and “1776” on back.

Cup, possibly Yorkshire (Swinton), dated 1777. Slipware. H. 3". Slip-trailed decoration includes the initials “I– S.”

Bowl, London, 1780–1790. Delftware. D. 5 7/8". A late example of English delftware. Similar neoclassical decoration was also used on creamware and pearlware

Basket and stand, probably Yorkshire, 1780–1790. Creamware. L. 6 3/8". Intended for confectionery or dessert. The detachable stand has a smooth bottom.

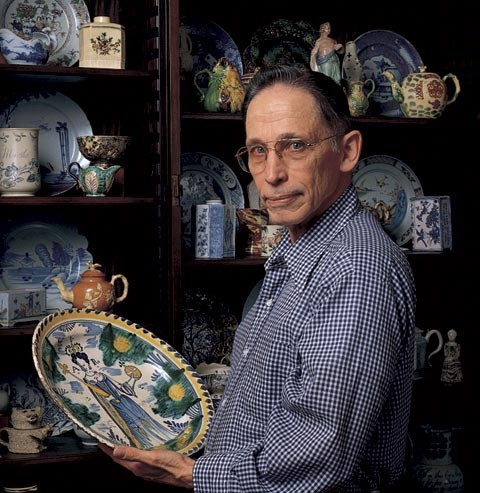

Troy D. Chappell.

As a collector, I am essentially curious, eager to discover, acquire, and learn. I was introduced to American and British decorative arts through the Colonial Williamsburg collections more than fifty years ago. Although evolving in several directions, my interest in English pottery began in earnest about 1969.[1]

After organizing my thoughts, the goal was to assemble and contrast pieces to demonstrate most of the manufacturing materials and forming techniques, manners of shaped and colored decorations, and progression of styles that dominated English trade and perceptions through the period of about 1630 to 1780. The mock eighteenth-century newspaper notice included in this article summarizes the breadth of my collecting project.

English pottery can be divided into two general categories: (1) earthenware, composed of low-fired clays that are usually covered in a lead glaze to reduce porosity and (2) higher-fired stoneware, its semivitrified composition providing an equivalent imperviousness to liquids. Within these two groups there are many distinct types of English pottery, including delftware or tin-glazed earthenware, slipware, redware, agateware, salt-glazed stoneware, and cream-colored ware.

Seventeenth-century slipware and delftware anchor the collection since the offhand medieval and earlier pottery was made for restricted local or personal needs as the occasion demanded and does not seem to have been well organized for distribution. At the other end of the time spectrum, products introduced later than 1780 creamware are curtailed because my scope seeks to reveal the sensibilities or amplifications of independent workers before the advent of absolute duplications through improved power machinery.

Some collectors focus on dated or unusual specimens, while others care for handsome objects. I try to emphasize the diverse and sometimes subtle ways by which potters and decorators produced their wares. For example, delft artisans painted quickly on porous tin-glazed surfaces with tinted solutions that did not show great distinctions of color; yet they achieved shaded perspectives, balanced polychrome coloration, and incredible fine-line imagery, much as would miniaturists. Notwithstanding this, my favorite delft piece shows how a few brushstrokes can convey the tranquility and beauty of a swan beside a ruined column (fig. 14). Another major interest for me lies in the fabrication of molds for slip casting or press molding. The carving of models to make these molds indicates tremendous proficiency with the materials at hand and in dirty work environments. Subsequently, complex multipart master and working molds are made from the models. These molds were critical to the potter’s need to produce many items quickly and efficiently and to sell wares promptly for a profit. Commerce, after all, not patronage or artistic exploration, drove the daily operations of the English potter.

Assembling an instructive collection of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century English pottery is a fascinating experience in light of the diversity of technical innovations and style transitions. Among the period manufacturing techniques represented by the collection are hand modeling, wheel throwing, lathe turning, slip casting and press molding. The judicious study of this body of work can provide many insights into the origins of the patterns and shapes that correspond to technological capabilities and social fashion.

The objects illustrated in this article represent an overview of the collection that at present numbers approximately 240 pieces. Several infrequently encountered forms and patterns of English pottery were chosen in the winnowing process. In addition, many of these pieces have never been illustrated elsewhere; most of the rest are shown for the first time in almost thirty years. Taken as a group, the choices promote the charm of handwork that was especially fluent during the middle part of the eighteenth century.

My favorite in the collection to date is a salt-glazed stoneware cream pot that presents a graceful, silver shape with sweeping tripod having one “tapping” foot (fig. 11). The body is highlighted with an added accent of blue applied relief, a technologically difficult use of colored clay. The circumstance of its coming into the fold is a classic story of collector patience. Initially, I had seen this piece illustrated and I sensed that it was archetypal. Over a twenty-year period, I passed over two other related pieces that did not measure up as well in my mind. One day, an American ceramic dealer’s brochure appeared in the mail and amazingly the same little jug was there. I was able to obtain the very pot I had seen published years before. I hope that kind of magic will come again!

Development of the Collection

The idea of forming a collection began inadvertently with the purchase of an attractive white salt-glazed deep dish. Within a year, my interests had grown to encompass a fuller array of useful and ornamental pottery. From the outset I perceived that a comprehensive collection might not be possible. Instead, I sought to assemble a representative grouping. If I were to begin today, I would concentrate on English delftware regardless of period. I find delftware refreshing because of its variety of designs, colors, and shapes in a medium easily reflecting the touch of an individual potter or decorator.

Starting off I ran into the ordinary bumps and bungles. An early visit to a dealer was less than successful when I asked for the wrong thing based on a limited knowledge of the distinction among specific pottery types. After this blunder, the importance of seeing and understanding the subtleties of English pottery wares became one of my lifelong learning experiences. Many dealers and curators were very helpful with the reliable information they passed on to me. The generosity of these dealers led to my acquaintance with specialty libraries in their New York antique shops and I acquired many of the same books for my reference library. Although many volumes written in the early twentieth century are fanciful or outdated, they still contain many unique illustrations that provide important reference material.

Today, archaeologists and researchers provide new discoveries in journals and independent volumes. And the largesse of museum donors and private collectors has made it possible to share treasures in stunning detail with wonderful illustrated books. Great progress has been made in understanding the production, distribution, and use of early English pottery. These clarifications, though, also bring dilemmas to long-term students who are particularly freighted about choosing between old and new mind-sets for attributing or dating pottery. So, we now tend to jot down things with pencils having erasers.

I have written a personal-use catalog of the collection that serves as a guide to new acquisitions, records discoveries such as provenance, and integrates findings from recent research. Only this year, a teapot on my initial want list has made it to my cabinet. When the time comes for me to relinquish my stewardship over these wares, there will remain a memory book showing a record of why and how well one collector, on a compressed scale, was able to represent the history and workmanship of a nascent industry.

My collecting project aims at a total of three hundred or so items. Because of the large variety of delftware decoration, there is necessarily a large number of plates. However, I consciously try to acquire a diverse number of forms among all wares whenever there are options in the market.

Deaccession from my collection has happened but twice. This low number may result from luck, studied selection, or simply stubbornness. In one case, it took nearly fifteen years to finally let go of a desirable object even though it did not fit into my collecting framework. I do admit that other candidates for removal may exist. In certain instances, I should like to trade up marginally to improve condition, but scarcity has precluded my doing it. And, so it goes for others and myself.

Personal Sentiments

The matter of discipline in collecting is important to me. A study collection benefits from the formation of well-defined objectives for acquiring examples that logically express the breadth and depth of a subject. These goals, of course, have to be attainable in light of a collector’s resources. Numerical growth in lieu of quality is only a passing satisfaction. That is not to say that each purchase need be rare, but additions should increase the merits of the assemblage as a whole. I try to follow guide points without being overly parochial. Therefore, along the way there always can be space for that unexpected, particularly compelling piece to be found by serendipity.

Collecting also produces profound experiences when studies and related acquisitions are mutually stimulating. Expansion without insight is a sterile exercise. In this regard, it is advisable to be a wary reader and observer because in recent years folklore and earlier beliefs have been challenged by new archival research and clear archaeological findings.

New evidence is being gleaned from merchant accounts, bills, petitions and patents, parish registers, and probate inventories; the earth is yielding clues in the guise of unfinished potsherds from waste dumps and actual factory sites. The net assessment is that, despite the identification of hundreds of potters in the historical record, extant pots cannot be easily linked to those specific persons. Estimating the age and origin of pottery is still a challenge in spite of nearly a century of research.

It seems worrisome at times that the secrets of ancient worlds are more discernible than events from our western culture within the last four hundred years. Theories regarding regional origins, especially for tin-glazed earthenware, have collapsed when confronted with the truths that many potters and painters were itinerant as well as eager to pirate most commercially successful improvements. Thus, reliance on retrieved oven wasters instead of fragments from completed samples is a preferred safeguard before assigning a provenance.

Observations on Collecting

The inordinate expense of collecting antiques is sadly too well known, and the extensive holdings in some museums and certain large, private collections will never be duplicated. Even so, there are still opportunities to gather worthy objects in specialized areas. Careful selection and formulation of collecting themes can be as meaningful for major museums as they are for individual collectors.

Collecting slipware according to the methods of manufacture, for either body or surface, can provide a primary focus. In the family of delftware there is such a diversity of patterns and forms that many subsets can be constructed. For example, studying the way trees have been depicted, whether creatively or realistically drawn, can provide a lively collection that cuts across both time and stylistic considerations. One could simply focus on the large variety of plate rim decorations or shaped edges. Many directions are open.

Under the heading of deliberately modified colored wares, the range of colors, or even their arrangement on a single piece, recommends groups for further identification and study. Salt-glazed stoneware invites great exploration. Consider the use of a single decorative color like cobalt blue. This gamut ranges from splashes and dabs, filling for cast or incised relief, mold-applied blue clay, color dips, and enamel highlights. Enameled scenes and colored ground wares open the door to other opportunities. Later pottery, especially creamware, lends itself to a variety of factory and decorator assignments. The whole realm of parallel designs makes fruitful study, as do regional and site-specific characteristics.

After all is said and done, why pursue collecting? There are several admirable reasons ranging from preservation to education, but from a simple perspective I find it is fun to converge along multiple critical paths reaching a project goal. In other words, it is like connect-the-dots to complete a picture.

I also collect for pleasure, for the aesthetics, and to assuage an inner challenge to piece together a historical puzzle in industrial development. This is done with an eye to studying and finding quality items of many forms and patterns while insuring they are true and fair representatives of the time. Ultimately, I guess, all is rooted in my engineering proclivity.

I must be careful, however, not to become caught up seeking just those unusually designed or nearly perfectly formed items that are not representative of the period’s more typical household objects. The exceptions are those objects associated with marriage, avocation, trade, or political commemoration. It should be remembered that the bulk of the production was probably unadorned and therefore more frequently discarded through passing years. Pristine and/or commissioned works were specialties often destined, like silverware, for ostentatious display in upper-strata homes.

One can read, study pictures, and view objects behind glass. Yet the most significant insights come from lifting and handling many items yourself. Avail yourself of occasions to do so with a compatriot at shops, auctions, and museum reserve areas. You will need to use several of the senses for comparison judgments.

Today, ceramic repair borders on complete re-creation of the object, making handling the wares essential. I can accept mild blemishes, but not eyesores. Small imperfections, however, can reveal insights into technological processes not otherwise detectable. Small chips or uncovered spots, for example, can show the succession of glaze or slip applications.

The acquisition phase of collecting is perhaps the most daunting. Availability and price in the markets can cause serious consternation about whether or not to purchase at the moment. This is surely a longstanding lament among collectors. Through the years there has been only one instance when I felt I found a real bargain. We all hope to repeat similar exciting situations!

All collectors usually have a haunting memory of the missed chance. Early on, these lost opportunities happened more frequently to me because initially I was annoyed by chips and hairlines. Later it can be sobering to find one’s unrealized purchase in some museum storage area.

One disadvantage of developing an American collection of English pottery is that much of the current research is based on archaeological finds associated with factory sites, which of course are in England. From our once-colonial shores, however, there are now notable revelations about this same microcosm of household ceramics. In fact a considerable profusion of imported examples has been identified from historical records and from items recovered at early domestic American sites.

Finally, I have gathered some advice for newcomers collecting English pottery; namely: (1) refrain from using personal generic names (Astbury, Whieldon, Bowen), (2) use archaeological finds and marked specimens to assign source attributions, because many potters made similar goods, (3) remember that ground color is often more the function of cleanliness of materials and firing conditions than age or origin, (4) develop and hold, within reason, your own assessments of dating variations among scholars in order to bridge unexplained time gaps, (5) remember that the field is not closed since exciting authentic items do appear, (6) minimize the use of subjective word evaluations (rare, unique, fine), and (7) follow your instincts and be patient in reaching your goals.

Continued Journey of Thoughts

Have you ever wondered who has held the very same piece that you now own? Between the maker and the last collector those persons are usually anonymous. I try to update provenance on every item, and I keep note card guides to similar examples. Perhaps such searches for satisfying associations are a subtle spur onward for everyone, beyond the value of any newly discovered information about history.

Apart from limited bequests, my accumulated wares will eventually filter down to future ceramic hunters. To record my ownership in the larger chain of the collecting continuum, I have affixed my personal label to those objects in my care. Its design was adapted from the incised border of a salt-glazed stoneware mug.

Because I prefer a variety of different wares, I have chosen to mingle them radically while they are on private display at home. Aside from space considerations, I like the banked effect of mixed textures, colors, and reflections. In imagining a public exhibition of my wares I would add supplementary texts, drawings, and miniature dioramas that would explain potting site layouts, materials preparations, transportation of wares, and differentiation of constructions and functions among firing ovens and kilns. Samples of pot-working tools would also be at hand.

As remarked, there are many approaches and satisfactions when collecting ceramics. I earnestly invite readers to find their own path. In doing so they may develop an enthusiasm as great as my own.

Adapted from the definitive, on-going manuscript catalog of the Troy Dawson Chappell Collection, An English Pottery Heritage—A Survey of Earthenware and Stoneware 1630–1780.