The base of Tildon Easton’s stoneware kiln in Alexandria, Virginia, excavated in 1984 by the city archaeologists. The updraft kiln, built in 1841, measures 12' across. Volunteers are excavating the waster dump, lower right. The adjacent well (at bottom) is of a later date. (Photo, courtesy Alexandria Archaeology Museum.)

Milk pan, Tildon Easton, Alexandria, Virginia, 1841–1843. Salt-glazed stoneware. D. 10". This milk pan shows the typical squared rim, pouring spout, and lug handle. A version of the three-petal tulip is seen under the spout. Also under the spout is the mark “TILDON EASTON” stamped with 16-point metallic type. (All objects courtesy Alexandria Archaeology; photos by Gavin Ashworth unless otherwise noted.)

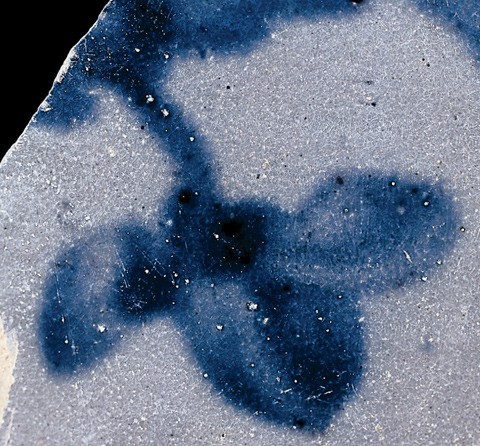

Detail of milk pan illustrated in fig. 4. This three-petal stylized tulip is a typical element of decoration on Easton’s pottery.

Milk pan, Tildon Easton, Alexandria, Virginia, 1841–1843. Salt-glazed stoneware. D. 11". The placement of the fiowers, alternating above and below an undulating vine, is a common design.

Jar, Tildon Easton, Alexandria, Virginia, 1841–1843. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10". The placement of the flowers in line with the foliage is less common.

Jar, Tildon Easton, Alexandria, Virginia, 1841–1843. Salt-glazed stoneware. D. (of rim) 7". This example shows the typical squared rim and lug handle. Leaves surround the ends of the lug handle springing from a garland of leaves, and the typical Easton flower appears on the front and sides.

Milk pan, Tildon Easton, Alexandria, Virginia, 1841–1843. Salt-glazed stoneware. D. 8". The five-petal flower has been found on only two vessels.

Milk pan, Tildon Easton, Alexandria, Virginia, 1841–1843. Salt-glazed stoneware. D. 11". Flowers appear at the ends of the side branches in this forward-facing design.

Jar or vase, Tildon Easton, Alexandria, Virginia, 1841–1843. Salt-glazed stoneware. D. (of base) 3 1/2". This unusual vessel has the typical Easton flower but an ovoid shape and flared base.

Tildon Easton’s pottery kiln was excavated in 1984, but recent information from a descendant of the potter and the Alexandria Archaeology Museum’s revived focus on locally produced pottery have led to a new look at Easton and his wares. In particular, we have begun to look at ways in which Easton’s pottery might be differentiated from other Alexandria stoneware.

Easton manufactured both earthenware and salt-glazed stoneware for a very short period of time, between 1841 and 1843. One of the few surviving references to his business is an announcement in the Alexandria Gazette on June 10, 1841, for the opening of his “New Stone and Earthen Ware Manufactory.” He claims that he “has on hand, and is constantly manufacturing, STONE AND EARTHEN WARE, of every description, and of the best quality. . . .”

Tildon Easton came to Alexandria from Maryland by 1832.[1] In order to operate a pottery, he would have needed experience. He may have worked or apprenticed at the Wilkes Street pottery, which was the only one in Alexandria in the 1830s. If so, Easton would have learned his skill from Alexandria’s best-known stoneware potter, B. C. Milburn, who managed the pottery for H. Smith & Co. before purchasing it in 1841. This would help to explain the similarities between Easton’s cobalt-decorated stoneware and stoneware with the impressed mark of H. Smith & Co.[2]

Easton’s stoneware kiln was discovered on a construction site under four feet of fill (fig. 1). All but the lowest four courses of brick had been removed in the twentieth century. The kiln base was still surrounded by the lower levels of an extensive waster dump containing kiln furniture and more than 5,000 sherds of Easton’s pottery, representing at least 677 distinct vessels.

More than half of these sherds were of salt-glazed stoneware. The impressed mark “TILDON WASTON” appears on twenty vessels from the waster pile, including an ovoid flask, three jugs, two bottles, two smaller bottles, and eight cobalt-decorated milk pans (fig. 2). Four milk pans have one-and-one-half-gallon capacity marks. The same mark appears on two earthenware milk pans.

Earthenware includes over fifty flowerpots; most are unglazed but a few exhibit spots of green glaze and crimped flanges and rims. Milk pans and utilitarian pots with glaze on the interior are also common. More unusual earthenware forms are small banks and a glazed bowl like those made by Alexandria potter Henry Piercy at the turn of the nineteenth century.

Undecorated stoneware includes straight-sided bottles, small ink bottles with a greenish glazed interior, and ovoid flasks. Some of these vessels are a light buff color, which appears to be deliberate rather than an accident of firing.

Around 150 gray salt-glazed stoneware vessels have brushed cobalt decoration in rather florid floral and foliate patterns. Most are milk pans, followed by jars. All of the milk pans have a slightly sloping profile, a narrow squared rim, a pour spout, and plain lug handles. The shape is similar to some found at the Wilkes Street pottery bearing the marks of H. Smith & Co. and B. C. Milburn, although most examples from Wilkes Street have a rounder rim. Easton’s jars are straight-sided, curving in below a narrow squared rim, usually with plain lug handles just below the rim. Most jars from Wilkes Street are ovoid. Straight-sided jars marked Smith or Milburn usually have no handles and either a rounded rim or a ridge below a squared rim. One pitcher rim was found, with a shape similar to those from Wilkes Street. Easton’s small flowerpots have no parallels at the Wilkes Street pottery.

The decoration on Easton’s stoneware shares similarities with the Wilkes Street pottery, but several differences are also evident, as noted below:

Flowers: Three-petal flowers (fig. 3) are found on twenty-four examples of Easton’s stoneware. These most likely depict tulips, a common theme on both stoneware and earthenware since many potters were of German origin. Easton’s tulips, with outward-turned petals, closely resemble the so-called trinity tulip motif seen on Pennsylvania Dutch folk art. Several of these flowers appear on one milk pan, alternating above and below undulating foliage (fig. 4). Sometimes the flowers are in line with the foliage (fig. 5). These flowers spring from a narrow curving stem and are made up of seven brushstrokes: one at the base, and two for each petal. Sometimes there is a space within the central petal (figs. 5, 6), but there is a continuum and no clear indication that more than one decorator was employed. A three-petal tulip is seen on a few examples of Milburn’s pottery, but his petals turn inward.

Five-petal flowers (fig. 7) are found on only two vessels. On the example shown, this flower is centrally placed on the front of the milk pan, with branches on either side. The second flower’s petals are closer together and more tuliplike, but the flower’s placement cannot be determined from the small fragment. One fragment from the Wilkes Street pottery has a four-petal flower similar to this.

Foliage: The foliage ranges from well-executed rounded leaves (figs. 8, 9) to quickly drawn pointed leaves (fig. 7). While at first these may appear to be drawn by two different hands, there is a continuum from one style to the other.

Handles: Easton places a cobalt leaf above and below the ends of his lug handles (fig. 6). The leaves are sometimes attached to a vine and are sometimes separate. At Wilkes Street, similar treatment is found on some handles. Other Wilkes Street handles have a blue stripe above the entire handle or surrounding the handle, or sometimes the handle is undecorated.

Placement: On most of Easton’s pots, lavish decoration winds around the pot (fig. 5). While a few examples have forward-facing designs with a central flower or foliate branch (figs. 7, 8), the foliage continues on the back of the pot. In contrast, most of the pots from Wilkes Street have forward-facing designs, with a central flower and only small sprigs of leaves or other small decorative elements appearing on the reverse. Even when foliage wraps around a Wilkes Street pot, there is generally a beginning and an end, with a blank area on the reverse.

Tildon Easton’s wares are known almost exclusively from the archaeological finds at his kiln site. Even though some of the vessels are stamped with his name, only one surviving antique pot is known. An antique dealer discovered the marked milk pan, decorated with the typical pendant flower and large leaves, on a porch in Red Hill, Pennsylvania, in the early 1990s. He sold it to the current owners at Renninger’s Antiques Market. They only just learned, through an Internet search, that this pot was from Alexandria. Perhaps the information provided here will lead to more discoveries.

Less than two years after his manufactory opened, a notice in the Alexandria Gazette announced that Easton was bankrupt.[3] One might speculate that he was unable to compete with Milburn’s successful Wilkes Street Pottery, which had been operating under different owners for thirty years.

The last Alexandria reference to Easton is in tax records for 1846. His wife, Rebecca, continued to be listed in church records until 1849, and she and their children were listed in the 1850 census. After leaving Alexandria, Easton had a surprising change in careers: he studied the new field of dentistry at the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery. Founded in 1840, this was the first school of dentistry in the United States. Easton is listed in a Baltimore directory from 1858–1859 as “Dr. Tildon Easton, dental surgeon.” By 1860 Tildon and Rebecca were living in West Virginia; they both died in 1885. Tildon’s legacy lives on in the stoneware collection of the Alexandria Archaeology Museum.[4]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to thank the staff and volunteers at the Alexandria Archaeology Museum for their assistance with the excavation and processing of the artifacts. Volunteer Vivienne Mitchell and genealogist Joy Talburt Biddison provided historical information about Easton.

Barbara H. Magid

Assistant Director

Alexandria Archaeology Museum

<barbara.magid@ci.Alexandria.va.us>

Records of the Trinity United Methodist Church, Class Membership Lists, 1802–1849.

Barbara H. Magid, “An Archaeological Perspective on Alexandria’s Pottery Tradition,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 21, no. 2 (winter 1995): 41–82; Suzita C. Myers, The Potters’ Art: Salt-Glazed Stoneware of 19th-Century Alexandria, Alexandria Papers in Urban Archaeology, Museum Series, no. 1 (Alexandria, Va.: Alexandria Urban Archaeology Program, 1983).

Alexandria Gazette, February 20, 1843. He was to go to court on May 8 to discharge his debts, but the court records for that day are missing.

Easton’s fate and more of his family history were elucidated by Joy Talburt Biddison, whose husband is a direct descendant.