View of the archaeological excavations at the Mansion Pottery site. (Photo, Jonathan Glenn.)

East Liverpool, Ohio. Lithograph, Albert Ruger and J. J. Stoner, 1886. Arrow indicates city block on which the Mansion Pottery site was located. (Courtesy, East Liverpool Museum of Ceramics.)

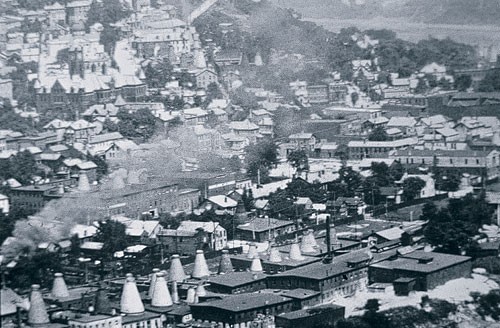

Photograph of East Liverpool, Ohio. Undated. (Courtesy, East Liverpool Museum of Ceramics.)

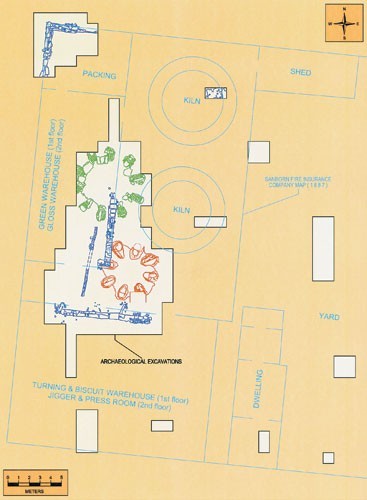

1887 Sanborn Fire Insurance Company Map superimposed on a drawing of the Mansion Pottery excavation site. (Drawing, Thomas G. Whitley and Jonathan Glenn.)

Spittoon, James Salt and Frederick Mear, East Liverpool, 1842–1853. Yellow ware. H. 8 1/4". One of the few whole vessels attributable to the Salt and Mear ownership of the Mansion Pottery. (Courtesy, East Liverpool Museum of Ceramics and William C. Gates Jr.)

Mansion House Hotel building, undated photograph. Note the mold board, with several pots on it, that extends from a second-story window. (Courtesy, East Liverpool Museum of Ceramics.)

Overhead view of the first kiln, illustrated in fig. 1, showing the fireboxes. (Photo, Jonathan Glenn.)

Chamber pot fragments, Mansion Pottery, East Liverpool, Ohio, 1842–1860s. Bisque yellow ware. Decorated with dark brown and pumpkin bands, and slip-trailed pumpkin lines. (Photo, Melinda McNaugher.)

Teapot and jug fragments, Mansion Pottery, East Liverpool, Ohio, 1851–1860s. Rockingham-glazed yellow ware. These relief-molded vessels illustrate the Minister/Apostle motif (at left) and the “Rebekah at the Well” motif (at right). (Photo, Melinda McNaugher.)

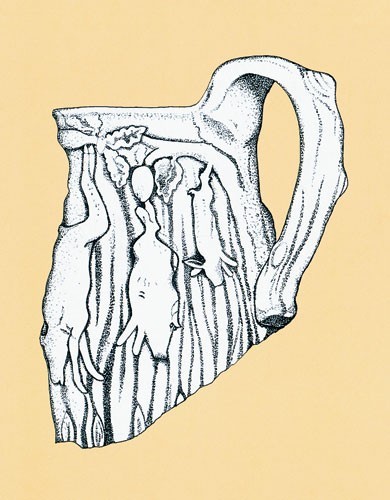

Drawing of a Rockingham-glazed yellow ware pitcher fragment with hanging game motif. (Drawing, Martin T. Fuess.)

Yellow ware stilt with the name “Robert” inscribed into the clay while the clay was wet. The name is partially obscured by Rockingham glaze drips. (Photo, Melinda McNaugher.)

Hollow ware fragments, Mansion Pottery, East Liverpool, Ohio, 1842–1860s. Bisque yellow ware. Decorated with dark brown and pumpkin bands, pumpkin slip trails, and cat’s-eye motif showing slip imperfections. (Photo, Melinda McNaugher.)

Teapot lid, Mansion Pottery, East Liverpool, Ohio, 1842–1912. Bisque yellow ware. (Photo, Melinda McNaugher.)

Colorless glazed yellow ware vessel fragments showing glaze imperfections. (Photo, Melinda McNaugher.)

View showing the fireboxes of the second kiln. (Photo, Jonathan Glenn.)

Spittoon fragments, Mansion Pottery, East Liverpool, Ohio, 1842–1860s. Yellow ware. An example of Rockingham glaze (left); an example of bisque (right). (Photo, Melinda McNaugher.)

Mugs, Mansion Pottery, East Liverpool, Ohio. Yellow ware, 1842–1860s. An example of bisque with slip bands (left); bisque with relief molding (center); slip-banded with colorless glaze (right). (Photo, Melinda McNaugher.)

Bowl, Mansion Pottery, East Liverpool, Ohio, 1842–1860s. Partially reconstructed London-shape bowl with dark brown and pumpkin bands and slip-trailed pumpkin lines. (Photo, Melinda McNaugher.)

Bowl and jug fragments, Mansion Pottery, East Liverpool, Ohio, 1842–1860s. Yellow ware bisque vessels with bands, cat’s-eye, and earthworm slip motifs showing slip imperfections. (Photo, Melinda McNaugher.)

Yellow ware kiln furniture, including stilts and spurs. (Photo, Melinda McNaugher.)

Photograph of a sagger in fill of biscuit warehouse. (Photo, Barbara Gundy.)

Baker fragment, Mansion Pottery, East Liverpool, Ohio, 1842–1912. Yellow ware with Rockingham glaze. (Photo, Melinda McNaugher.)

Bottle stoppers, Mansion Pottery, East Liverpool, Ohio, 1842–1853. Yellow ware with Rockingham glaze. (Photo, Melinda McNaugher.)

Chamber pot fragment, Mansion Pottery, East Liverpool, Ohio, 1842–1912. Colorless glazed chamber pot fragment with reddish brown and white slip bands, with common cable or earthworm motifs. (Photo, Melinda McNaugher.)

Molded jug fragments, Mansion Pottery, East Liverpool, Ohio, 1842–1912. Yellow ware bisque relief-molded jug fragments, with an example of a floral motif (left) and a thistle motif (right). (Photo, Melinda McNaugher.)

Yellow ware bisque sherds. Mansion Pottery, East Liverpool, Ohio, 1842–1912. An example of relief molding and dark brown and pumpkin slip bands (top left), a baker with relief-molded beading (top right), lathe-turned bands (bottom left), and dark brown and pumpkin bands with pumpkin slip-trailed lines and dots (bottom right). (Photo, Melinda McNaugher.)

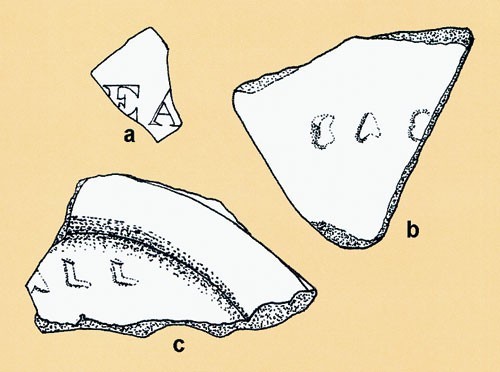

Illustration of three partial maker’s marks found on ceramic sherds at the archaeological excavation of the Mansion Pottery. (a) “. . . EA . . .” from the Salt and Mear operation; (b) an unidentifiable mark; and (c) “. . . ALL . . .” from the Croxall operation. (Drawing, Martin T. Fuess)

In 1991 archaeological investigations sponsored by the Ohio Historical Society and funded by the Route 30 Extension Project of the Ohio Department of Transportation were conducted at the Mansion Pottery site, the location of the third pottery established in East Liverpool, Ohio (fig. 1). James Salt, Frederick Mear, John Hancock, and James Ogden’s pottery was preceded only by James Bennett’s 1839/1840 pottery and George Harker’s 1840 Etruria Pottery and operated, under various ownerships and names, virtually uninterrupted until 1912. For clarity, the pottery is referred throughout this article as the Mansion Pottery, with references to its various owners where appropriate.

The Mansion Pottery was located two blocks north of the Ohio River in the south-central section of East Liverpool, on a block that included city lots 22, 28, and 34. The boundaries of these three lots were formed by Cherry Alley on the east, Washington Street on the west, Centre Alley on the north, and Second Street on the south (fig. 2). Historic documents indicate that the majority of the Mansion Pottery operations were located within lots 28 and 34, the westernmost two; therefore, archaeological investigations at the site were limited to these two lots.

East Liverpool, also called “Crockery City,” was the nation’s largest and most important production center for ceramic table and toilet wares during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, even surpassing Trenton, New Jersey (fig. 3).[1] Specifically, it was the major production center for Rockingham and yellow ware during the 1840s and 1850s. The operation of the Mansion Pottery from 1842 to 1912 spans virtually the entire period of East Liverpool’s dominance in ceramic manufacturing, although only Rockingham and yellow ware were produced there.

History of East Liverpool

East Liverpool was founded shortly after 1799 when Thomas Fawcett, his wife, Isabella, and their eight children emigrated from western Pennsylvania and purchased 1,100 acres of land there.[2] Fawcett platted the town on a portion of his land tract, using the New England-based grid system to create the pattern of rectangular blocks and lots on which the Mansion Pottery was sited. He called the town St. Clair—after Arthur St. Clair, the governor of the Northwest Territory—although the residents called it Fawcettstown, after its founder.[3] In 1803 Fawcettstown became part of Columbiana County in Ohio, which on March 1 had become the country’s seventeenth state.[4] During its early years Fawcettstown grew very slowly, having only five or six houses; a ferry is mentioned in an 1807 travel diary entry.[5] By 1816 the town, renamed Liverpool, still consisted of only a few dwellings, a grist mill, and a tavern, which doubled as the ferry house.[6] Despite its location on the Ohio River, the town was not an early manufacturing center, outcompeted by business centers in nearby West Union or Foulkstown (Calcutta) and Wellsville, and, in Pennsylvania, Little Beaver River, Little Yellow Creek, and Georgetown.[7] During the 1830s the town, incorporated as East Liverpool in 1834,[8] began to emerge as a local commercial center for agricultural products and boat building. It was not until the production of earthenwares began in 1839, however, that the town became established in an industrial niche that it would dominate over the next seven decades.

Into a community that had had four separate and distinct names in as many decades; that had been trice platted into inviting home lots; that had lost a shipping roadway from Cleveland to Wellsville; that had been beaten out of the county seat by New Lisbon; that had lost a decidedly needed railway to the lake by way of Warren and Ashtabula; that had had its commercial activities constantly circumscribed by Georgetown, Pa., Calcutta, Little Beaver Creek and Wells Landing down the river; that had suffered the losses of the devastating flood of 1832 and the resulting frequent withdraw of outside capital and capitalists to say nothing of the debilitating effects of the panic of 1837, from which it was then acutely suffering, came James Bennett, 28 years old, to build the first Crockery City Ware Plant and insure for it a future that even his effervescing, optimistic vision at the moment could not foresee.[9]

James Bennett, a yellow ware packer/apprentice at Newhall near Woodville, Derbyshire, England, emigrated to the United States in May 1834.[10] From 1837 to 1839 he traveled in the northeast and midwest, working at potteries in Jersey City, New Jersey, and Troy, Indiana.[11] Due to his ailing health and failing pottery, Bennett left Indiana in 1839 and headed toward Pittsburgh,[12] but after meeting with a local businessman in East Liverpool, Bennett decided to attempt to establish a pottery there.[13] Recognizing the clays in the area as good raw material for the production of yellow ware, the availability of coal for fuel, and the location of the town on the river as beneficial for market transportation, Bennett established East Liverpool’s first pottery in 1839 and fired his first kiln of yellow ware, consisting mainly of mugs, in 1840.[14] Bennett was successful in distributing and selling his first wares at a profit, thus establishing himself—and a potting industry—in East Liverpool. In 1841 Bennett encouraged his brothers to join him, and upon their arrival from England the Bennett Brothers Pottery began to produce the mottled, brown-glazed “Rockingham” ware in addition to yellow earthenwares.[15]

History of the Mansion Pottery

The Mansion Pottery was established in 1842, near the beginning of the potting industry in East Liverpool (fig. 4). Few of the general historic documents available contain detailed or extensive information about the Mansion Pottery, perhaps because two other commercial potteries had already been established in East Liverpool. The results of the archaeological investigations combined with the sparse historic documentation, however, provide a more detailed picture of the pottery, its owners and workers, the physical plant, methods of manufacturing, the products produced, and the markets in which they were sold. There is general consensus regarding the chain of ownership of the pottery, although specific dates and reasons for ownership changes vary.

The Mansion Pottery location was originally the site of a hotel. In 1832 one E. Carroll of New Lisbon, Ohio, erected a two-story, frame-and-hewn-timber building on the northeast corner at Second and Washington Streets that he called the Mansion House, believed to be named after a noted inn of the same name in Liverpool, England. Carroll built the hotel in anticipation that a proposed railroad would link East Liverpool with Lake Erie, providing a source of patrons for his hotel.[16] In 1833 Carroll opened his hotel and store. The railroad project collapsed when the economic Panic of 1837 occurred, Carroll’s investment failed, and the hotel building went idle.[17]

In 1842, at the lowest point of the severe 1839–1842 recession, four British emigrants—James Salt, Frederick Mear, John Hancock, and James Ogden—formed a pottery company and took over the idle Mansion House building.[18] Not much personal information is known about Salt or Mear prior to their establishment of the Mansion Pottery and, despite their involvement with the pottery over eight years, not many references to their partnership exist. James Salt was born in England in 1813; Frederick Mear was born in Burslem, England, in 1822.[19] One obscure reference to Salt and Mear comes in a letter written by Sarah Nixon Vodrey of East Liverpool to her son John Vodrey, who was then serving in the 46th Pennsylvania Volunteers:

so now, my dear boy i think i must draw to a close but i must tell Mr. Salt is very sick. he has the typhoid fever and they sent for fred mear. he came and has sold the pottery to Cartwright and company for the sum of 9 thousand and 500 Dollars. i think if Salt should get better they will leave town.[20]

The letter indicates that Frederick Mear had left East Liverpool prior to 1863 or 1864, which is confirmed by additional information: the Boston Directory places Mear as residing in Boston in 1852, and with a factory by 1853. Mear’s wares were advertised for sale in the Boston store of William F. Homer and Co. and Mear is listed as the agent.[21] His business relationship with the Homer general store lasted until at least 1857, when he is last recorded as an agent for his pottery. In 1858 Mear is listed as a potter residing at 79 Trenton Street, East Boston, but there is no mention of a pottery works. Mear’s obituary, which appeared in the East Liverpool Tribune on March 25, 1876, indicates that he was residing in Philadelphia just prior to his death.

John Hancock was born in Hanley, Staffordshire, England, and emigrated to the United States in 1828.[22] He erected a pottery in South Amboy, New Jersey, and the following year sent for his wife and son.[23] He then traveled with his son, Frederick, to Kentucky and worked in the stoneware pottery of George W. Doane before going to East Liverpool, where he joined with Salt, Mear, and Ogden to establish the Mansion Pottery.[24] He died the year that the Mansion Pottery was established.

As with Salt and Mear, little is known about James Ogden, other than that he retired from the Mansion Pottery partnership in 1842 or 1843, shortly after it was established.[25]

Salt, Mear, Hancock, and Ogden rented the empty hotel building for $75 per year and converted the structure into a working pottery building.[26] “Work benches were erected in the spacious rooms, the basement was turned into a sliphouse, an outside oven was built and the new firm . . . began production of yellow and Rockingham ware”[27] (fig. 5). Among the structural remains identified at the archaeological site are those of the original Mansion House Hotel and the original bottle kiln.

The hotel building served a variety of functions as the pottery operations expanded. The long axis of the building was oriented east to west and measured approximately 59 feet by 44 feet, according to the 1897 Sanborn Fire Insurance Company map. Documentation of the hotel building indicates that it was a two-story structure (fig. 6).[28]

Archaeological evidence adds that it had a foundation made of cut sandstone block and a basement with a brick floor. The cut sandstone blocks are ill-fitted and vary in size and shape; most are rectangular and measure at least twelve inches by ten inches by eight inches. Sand and clay are present in some of the foundation wall interstices, but these appear to be unintentional fillings of the spaces that occurred when the walls were buried, rather than intentional mortar. The preserved height of the foundation walls ranges from five feet to seven feet.

The hotel’s northern foundation wall appears to have served as the southern wall for the kiln hovel surrounding the southernmost and earliest bottle kiln located on the site. The hovel connecting the hotel building with the kiln would have protected the workers and the wares from rain and snow, allowing production to continue during inclement weather. The hotel’s basement floor was constructed of red brick and soft lime-sand mortar, the bricks laid face down in two vertical courses generally oriented north to south. The basement floor was only partially exposed, so whether brick covered the entire basement area is not known. The brick floor was laid directly on the subsoil. A depression containing an unstratified sandy matrix mixed with a large number of small oyster shell fragments was identified. In addition, a large area of potter’s clay abutted the eastern edge of the floor, which suggests that clay was being stored, processed, or discarded in the basement.

The excavation of the Mansion House Hotel, used as the biscuit warehouse, determined that the basement fill was comprised of materials resulting from the razing of the building and the in-filling and grading of the site by heavy machinery. Since the basement fill could not be directly related to the site’s pottery operations, only a sample was collected.

The earliest bottle kiln and its associated hovel were identified by foundation remains during the archaeological investigations. Bottle kilns with associated kiln hovels were present in Britain by the end of the seventeenth century.[29] Bernard Leach describes the bottle kiln form: “The bottle-neck kiln proper is made simply by heightening the wall and rounding it into a dome with a chimney above it. The packing is done through a doorway which is sealed with firebrick and clay before each firing.”[30]

In the northeastern United States the two predominant early kiln shapes, bottle and beehive, followed traditional British and Germanic forms that were transplanted to America. Since the East Liverpool potters were British immigrants, it is reasonable to assume that they would bring their kiln technology to their new environment, and, indeed, the bottle kilns shown in photographs of early East Liverpool potteries very closely resemble British kilns.

The earliest bottle kiln identified at the Mansion Pottery site was operated during Salt, Mear, Hancock, and Ogden’s ownership and is located directly north of the original Mansion House Hotel building. The remains of the circular kiln base include eight fireboxes constructed on top of the subsoil. From firebox exterior to firebox exterior, the kiln base diameter measures nineteen feet. The interior diameter of the kiln base, from interior firebox opening to interior firebox opening, measures approximately nine feet. Documentation indicates that the kiln built was ten feet in height and used for both biscuit and gloss firings.[31]

The fireboxes associated with this earliest bottle kiln were ovoid in plan and basin-shaped in profile (fig. 7). The smaller end of each firebox was oriented toward the center of the kiln. They were unlined and simple, shallow basins dug into the subsoil. The subsoil in and around the fireboxes was thermally altered by the intense heat of the fire in the kiln. The fireboxes’ fill was unstratified and consisted of masses of congealed cinder, ash, and slag. The presence of coal, cinder, ash, and slag indicates that coal was used to fuel the kilns. Small amounts of sand and silt were also present in some of the firebox fill but appear to have been deposited after operation of the kiln had ceased.

The only artifacts in direct association with the earliest kiln are ceramic sherds found in the firebox fill. A variety of forms, including colanders, bowls, nappies, chamber pots, teapots, pie pans, handles, and unidentifiable flatware and hollow ware vessels with colorless and Rockingham glazes, are represented in the recovered assemblage. Decorative techniques include slip-applied annular bands, slip-trailed designs (fig. 8), cat’s-eye, dendritic mocha, and relief-molded motifs. The colors of the slipped wares are dark brown, white, pumpkin, and blue, with the dendritic mocha motif in blue. Relief-molded motifs include ribs, braids, unidentifiable patterns, and the “Rebekah at the Well” motif (fig. 9). “The ‘Rebekah’ teapot design was regular and constant and became so popular that nearly all other potteries in the United States copied it.”[32] John Hancock has been mentioned as the original modeler of the Rebekah teapot, “which gave to East Liverpool a reputation through a dozen States.”[33] John Ramsay, however, firmly credits Charles Coxon, a modeler for Edwin Bennett in 1851, who is also credited with modeling Daniel Boone, hunting, wild boar, and hanging game motifs for pitchers (fig. 10).[34] It is unlikely that John Hancock designed the “Rebekah at the Well” pitcher that was manufactured at the Mansion Pottery, as his untimely death in 1842 occurred nine years prior to Charles Coxon’s original design. Kiln furniture, including fragments of sagger, sagger wad, stilts, and spurs, was also recovered from the southern kiln (fig. 11).

Many of the recovered ceramic artifacts exhibit a variety of flaws, ranging from surface and glaze loss, rough surfaces, warping, adhesions, and slip and glaze imperfections to burned or over-fired pieces. The quantity of defective sherds represented in the recovered artifact assemblage is not unexpected since any whole, unflawed vessels would have been packaged and sold, not discarded at the site.

Surrounding the bottle kiln on the east and west were brick foundation walls that appear to have supported a wooden kiln hovel. The kiln hovel walls were constructed of two courses of red brick laid on the subsoil, with their stretchers, or headers, placed parallel to the long axis of the wall but forming no specific bond pattern. No bricks were preserved along a portion of the eastern hovel wall foundation; however, there was a dark linear stain aligned with the brick portion of the wall, indicating the location of brick wall before it was removed. The southern hovel wall appears to have been the northern wall of the bisque warehouse, as previously discussed.

To the northeast of the earliest bottle kiln and hovel was a shallow, basin-shaped depression containing a concentration of ceramic sherds surrounded by a mixture of coarse silt, clay, ash, and a few small fragments of reddened sandstone. This feature appears to represent intentional dumping associated with the cleaning out of the kiln and fireboxes. Yellow ware, Rockingham, whiteware, and yellow bisque sherds; kiln furniture; and sagger and sagger wad fragments were recovered during the excavation of the depression. Vessels represented by the sherds include unidentifiable hollow ware, a mug, and a nappie. Relief molding and slip banding decorate some of these fragments. Many of these ceramics have flaws that include gouges, dragging, and smudging of the slip (fig. 12), adhesions (fig. 13), and glaze imperfections, among them a dark metallic residue that appears to be pulled glaze from the surface of the vessel (fig. 14). In addition to the ceramic sherds, other materials—brick, clay, coal, and sandstone fragments—were recovered from the depression.

The Mansion Pottery owners eventually purchased the hotel building, as well as additional structures, including a second kiln, which made it one of the largest potteries in East Liverpool by 1848.[35] The 1853 Sanborn Fire Insurance Company map clearly shows the hotel building and two bottle kilns located directly north of it, and the archaeological analysis also identified the second Mansion Pottery bottle kiln. The second kiln’s circular base included the remains of ten fireboxes. From firebox exterior to firebox exterior, the diameter of the second kiln base measured almost 23 feet north to south and a little over 21 feet east to west. The interior diameter of the second kiln base, from interior firebox opening to interior firebox opening, measured approximately 15 feet north to south and almost 16 feet east to west. Documentation cites the kiln size as 12 1/2 feet and constructed completely of firebrick.[36]

The second kiln’s fireboxes were rectangular in plan with their long axes oriented perpendicular to the perimeter of the kiln (fig. 15). Each of the fireboxes exhibited a prepared red and refractory brick infrastructure, including side, back, and bag walls and floors, laid on the subsoil, that sloped downward toward the kiln interior. Large sandstone slabs separated the fireboxes and provided the foundation for the inner kiln chamber. The subsoil in and around the fireboxes was thermally altered by the intense heat of repeated kiln firings. The average length of the fireboxes was slightly more than 41 inches and the average width was slightly more than 27 inches.

Numerous artifacts, most of which represent fill not associated with the Mansion Pottery, were recovered from the subsoil around the fireboxes: a ceramic smoking pipe stem, glass, metal, nails, shell, lithic materials, bone, and sherds of whiteware, pearlware, redware, stoneware, and white bisque. In addition to these artifacts, raw and partially fired clay, burned firebox residue, red and refractory brick, mortar, cement, and cinders were observed in the subsoil surrounding the fireboxes. The firebox fill—stratified bands of loose, coarse cinders, slag and ash, plus small amounts of sand and silt—yielded such artifacts as redware and pearlware sherds, small amounts of potter’s clay, fragments of glass, coal, and brick, as well as cinders and mortar.

The yellow ware and Rockingham ceramic artifacts recovered from the second kiln, which were similar to those recovered from the first, include a soap dish with drainer, colanders, spittoons (fig. 16), mugs (fig. 17), teapots, bowls (including the London shape [fig. 18]), unidentifiable hollow ware vessels, and handles with both colorless and Rockingham glazes. In addition to undecorated vessels, sherds with slip, relief-mold, and coggle-wheel decoration are present. The slip decorations include bands, cat’s-eye, and multiple trails in colored slip of white, dark brown, reddish brown, pumpkin, and blue. There are also mocha dendritic motifs in blue. Relief-molded motifs include scallops, plants, ribs, scrolls, bands, and unidentifiable patterns. One of the floral patterns appears to be the leaves of a tulip or corn plant.

As expected, the ceramic fragments recovered from the second kiln have imperfections such as rough surfaces, slip irregularities (fig. 19), and surface adhesions. Several fragments appear to be underfired, whereas others were so overfired that the yellow clay body now ranges from buff to reddish to gray in color. Similar to excavations at the first kiln, this kiln also yielded fragments of kiln furniture and saggers (fig. 20).

Historical and archaeological documents confirm that the original hotel building and two kilns were the site’s primary physical plant features during Salt and Mear’s ownership of the pottery. With limited interior space, Salt and Mear would have performed all of the various potting tasks in and around the hotel building. We know that Mrs. Salt sold the wares: “This energetic woman, with her voluminous skirts pinned high around her waist and balancing a basket of ware on her head, would tramp through town and along country roads selling or bartering.”[37] This firm secured skilled potters from England to work at the operation.[38] The Mansion Pottery operated under the ownership of James Salt, Frederick Mear, John Hancock, and James Ogden (Salt, Mear, Hancock, and Ogden) from 1842 to 1843, and under Salt and Mear until about 1850–1853. In 1851 or 1852 Mear moved from East Liverpool to Boston, and from 1852 to 1857 Salt and Mear leased the pottery to William G. Smith and Benjamin Harker.[39]

After the original ownership of the pottery failed, the pottery was acquired by Benjamin Harker Jr. and William Smith in about 1852[40] and became known as Harker and Smith. Smith was at that time a commission merchant and induced Harker, James Foster, and his son Daniel J. Smith to join him in the pottery operations.[41] During the period of Harker and Smith’s ownership, the pottery employed perhaps thirty workers and produced both yellow ware and Rockingham ware.[42] “Joseph Webber sifted slip in the basement, James Larkins, the town’s fastest thrower, would ‘catch’ work there occasionally and Enoch Lear was employed at the bench. The little plant seemed destined for success. Then came the flood of 1852, followed by the Black Year of 1854.”[43] The 1850 Federal Census, Industry Schedules of Ohio, indicates that the Mansion Pottery employed 32 workers, used 312 tons of clay, 10,000 pounds of lead, and 5,200 bushels of coal to produce 18,000 dozen pieces of Rockingham and yellow ware that were valued at $12,600. The schedule goes on to describe the use of horse and hand power at the pottery.

In 1854 East Liverpool experienced acute financial depression; banks and moneylenders failed, potteries went into bankruptcy, and private fortunes collapsed.[44] During these hard times the Harker and Smith ownership turned to paying their workforce in ware instead of currency.[45] Harker left the pottery in 1855 but remained in East Liverpool. He rejoined the Etruria Pottery and, in 1877, formed the Wedgewood Pottery with his sons.[46] When their financial backing failed, the Harker and Smith Pottery collapsed.

Historic accounts of the pottery trade in East Liverpool reveal that after running the place for several years Smith re-leased the pottery for the unexpired term of the lease to George Garner and James Foster.[47] Due to legalities surrounding the lease, Smith was taken in by Garner and Foster as a partner and the firm became known as Smith, Foster and Co. At the expiration of the lease, Foster and Garner returned the pottery to Salt and Mear.[48] Salt and Mear continued owning the pottery until April 22, 1863, when they sold the pottery to John Croxall and Joseph Cartwright for $9,500,[49] a real estate transaction that was described as one of the largest transactions in the area.[50]

Croxall was a member of a distinguished family of British potters, the first of whom, Thomas Croxall, came to East Liverpool in 1844. It was the Croxalls who purchased the Bennett Pottery when the Bennetts left for Pittsburgh. Croxall and Cartwright owned not only the Mansion Pottery but also the Union Pottery, which they acquired from Ball and Morris. The Union Pottery stood near the Mansion Pottery, across Second Street to the south. The joint output of both potteries, which once employed 100 workers, amounted to some $50,000 to $60,000 worth of yellow ware and Rockingham-glazed ware per year.[51] In 1876 the East Liverpool Tribune reported: “[A]ll the clay used at both factories is made at the ‘Union’ and carted to the ‘Mansion’, while all the saggers are made at the ‘Mansion’ and transferred to the ‘Union.’”[52]

The Mansion Pottery under Croxall and Cartwright’s ownership flourished and they built a new kiln, lined and topped another, and built a new two-story brick building which was used as a warehouse, greenhouse, and packing house. Croxall and Cartwright increased the capacity of the pottery works, and the “Mansion,” in connection with the “Union” pottery, was described as one of the best used potteries in East Liverpool.[53] At the close of the Civil War the pottery business boomed and the Mansion Pottery operation saw a number of years of continuous operation.

Sometime between 1853 and 1887 Croxall and Cartwright made major modifications to the physical plant at the site. The original Mansion House Hotel building remained in use for turning, jiggering, and pressing tasks as well as the biscuit warehouse; however, the two original kilns used by Salt and Mear were razed and a large building, which was to be used as a packing and gloss warehouse, was erected in their place.[54] Two new bottle kilns were then built to the north of the hotel building and east of the newly built packing and gloss warehouse, which was located on the northwest corner of the block, bounded by Washington Street on the west and Centre Alley on the north. According to the 1897 Sanborn Fire Insurance Company map, the building’s gable roof was oriented north to south and measured approximately 69 feet by 25 feet. The building appears to have been separated into two distinct activity areas: the northern portion served as the straw and packing warehouse and the southern portion served as the gloss warehouse.

Portions of all four basement walls of the packing and gloss warehouse building have been uncovered. The north and west walls were dry-laid cut sandstone block, each having an associated builder’s trench. The south and east walls exhibited two types of construction; one was cut sandstone block that was overlain by split tabular sandstone slabs, perhaps indicating that there were at least two construction phases for the wall. All four basement walls were dry laid without prepared mortar joints, and the blocks and slabs were ill-fitted. Some unintentional in-filling of the wall interstices by clay and sand had occurred. As the location of the building partially covers the area of the site’s two earlier kilns, the warehouse could not have been built or utilized until these kilns had been razed. Excavation shows that portions of the south and east basement walls were built directly on top of the second kiln’s two fireboxes, thus confirming the succession of construction for the warehouse as shown on the Sanborn maps.

The preserved height of the basement walls varies from 8 inches to nearly 5 feet, with an average width of 25 inches. The size and configuration of the walls indicate that they could have supported a substantial stable load, such as the two-story packing and gloss warehouse superstructure. The fill inside the basement was composed of discontinuous alternating bands of coarse compact sands and friable fine-grained ash/silt mixes. A chrome-wire-and-pipe shopping cart was noted at the lowest levels of this fill. Other artifacts associated with the fill include yellow ware, white ware, ceramic doorknobs, brick, sagger, metal, plastic, paper, screw-top bottles, rock, and machine parts. Doorknobs were never produced at the Mansion Pottery site, so their presence indicates that the fill had been brought in from other potteries or waster sites.[55] The wide range of artifacts highlights the mixed chronology of the fill, signifying that it probably was simply what was available when the ground surface was leveled after the gloss warehouse was razed, sometime between 1903 and 1913.

Excavations associated with the basement’s north wall yielded only fragments of saggers that can be associated with the pottery operation. These fragments represent at least seven saggers, some of which have interior glaze residue (fig. 21). Most of them represent thicker-walled vessels in a wide cylindrical form, but one is a short-sided box with a wall height of six inches and a base thickness of less than an inch. This small box sagger may have held some specialty item manufactured at the pottery.

Also identified was a builder’s trench located along the north basement wall that yielded such artifacts as sherds of yellow ware, Rockingham, whiteware, pearlware, redware and stoneware fragments, and yellow bisque, as well as kiln furniture, sagger, and sagger wad fragments, glass, metal, wood, bone, a metal hinge, and nails. The yellow ware forms include chamber pots, pitchers, spittoons, teapots, nappies, bakers (fig. 22), pie pans, bowls and cups in the London shape, handles, and other unidentifiable hollow ware, and flatware vessels. Two Rockingham-glazed bottle stoppers (fig. 23) complete the identified forms; they are octagonal in-shape and taper to a narrow neck with an unglazed inset flange. Slip designs represented in the builder’s trench artifacts include bands, common cable or earthworm (fig. 24), trailed, and dots in blue, white, dark brown, pumpkin, and reddish brown, as well as mocha dendritic in blue. Relief motifs are scallops, floral including tulip or corn (fig. 25), fleurs-de-lis, beads (fig. 26), vine, flutes, and darts. In addition, there is an ornate jug with the Minister/Apostle motif, with arched windows that each contain a saint or religious figure (fig. 9). This design was registered in March 1842 by Charles Meigh of the Old Hall Works in Hanley, England.[56] Again, manufacturing flaws such as glaze and slip imperfections, adhesions, warping, and cracking of the clay body appear on a number of the ceramics recovered from the builder’s trench. Cinders and brick fragments were also observed in the trench.

The 1897 Sanborn Fire Insurance Company map shows the location of two kilns built at the site by Croxall and Cartwright. Brick rubble is the only archaeological evidence for the locations of these kilns and confirms the Sanborn map locations. Both red and refractory brick fragments, a portion of which form an arc, were present. Neither the fireboxes nor the superstructure of these two later kilns was preserved, although there were associated artifacts: sherds of yellow ware, Rockingham, white ware, and pearlware; sherds of yellow ware and whiteware bisque; a piece of partially fired clay; kiln furniture; sagger and sagger wad fragments; glass; and modern historic artifacts. The presence of the latter indicates that these deposits represent fill.

John Croxall bought out his partner’s interest in the firm in 1888 and brought his two sons, George and Joseph, into the business (fig. 27).[57] Under the name J. W. Croxall and Sons (although popularly known as the Union-Mansion Pottery), the firm produced Rockingham spittoons, bedpans, foot warmers, pitchers, teapots, nappies, bowls, and mugs, as well as yellow ware butterpots, mugs, bowls pie plates, pitchers, and covered chamber pots.[58] In January 1898 the firm changed its name to Croxall Pottery Company. Despite numerous ownership changes after 1887, the physical plant and tasks associated with the buildings remained essentially unchanged until the cessation of potting at the site circa 1908. The original Mansion House Hotel building continued in use as the turning, jiggering, and biscuit warehouse and press room. The second building constructed at the site continued to be used as a packing, greenware, and gloss warehouse, and the two later kilns remained in operation. By 1913, however, all traces of the pottery’s physical plant had been erased, and the land on which the Mansion Pottery had operated for some seventy years was acquired shortly thereafter by the City of East Liverpool. The location then served as the site of a “tabernacle” for the famous evangelist Billy Sunday and, by 1923, as a public playground.

The Mansion Pottery is one of only two potteries that have been excavated in East Liverpool, a city that once produced half of all the ceramics in the country. Today the Mansion Pottery site is under a highway, the construction of which was the catalyst for uncovering the history of the pottery.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank the following individuals and groups for their contributions to and participation in the preparation of this article: The Ohio Department of Transportation and Paul Graham, Assistant Administrator, Office of Environmental Services, for their permission to use the excavation data; the Ohio Historical Society and Martha Otto, Curator of Archaeology, for permission to photograph the collections and use the images; Timothy Brookes, President, East Liverpool Historical Society; The East Liverpool Museum of Ceramics, Phil Rickerd, Caretaker, and Sarah Vodrey, Historic Site Manager, for access to their collections and permission to use historic map images; Melinda McNaugher for photographing the artifacts; Thomas Whitley and Jonathan Glenn for generating and manipulating the site mapping; Martin Fuess for illustrating the artifacts; Verna Cowin, William Gates, J. Garrison Stradling, Jonathan Glenn, and Chris Espenshade for editorial and review expertise; Skelly and Loy, Inc.; and Michael Baker Jr., Inc.

William C. Gates and Dana Ormerod, “The East Liverpool Pottery District: Identification of Manufacturers and Marks,” Historical Archaeology: Journal of the Society for Historical Archaeology16, nos. 1–2 (1982), p. 3.

William B. McCord, History of Columbiana County, Ohio, and Representative Citizens (Chicago: Biographical Publishing Co., 1905), pp. 286–87.

Ibid., p. 287.

William C. Gates Jr., The City of Hills and Kilns (East Liverpool, Ohio: The East Liverpool Historical Society, 1984), pp. 10–11.

Ibid., p.11. The travel diary refers to the diary of Fortesque Cuming, who passed through the town in 1807. Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., Early Western Travels, 1748–1846, 32 vols. (Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Co., 1904), vol. 4 (1807–9), Cuming’s Tour to the Western Country, by F. Cuming, p. 96.

Gates and Ormerod, “The East Liverpool Pottery District,” p. 3.

Gates, City of Hills and Kilns, pp. 12–13.

Ibid., p. 19.

Harold B. Barth, History of Columbiana County, Ohio (Topeka and Indianapolis: Historical Publishing Company, 1926), pp. 196–97.

Edwin Atlee Barber, Pottery and Porcelain of the United States: An Historical Review of American Ceramic Art with a New Introduction and Bibliography (Watkins Glen, N.Y.: Century House Americana, 1971), p. 192.

Ibid., p. 192; Loretta M. Riles, “James Bennett, Pioneer Potter 1812–1862” (unpublished manuscript, East Liverpool Museum of Ceramics, 1980), pp. 2–5.

Riles, “James Bennett, Pioneer Potter 1812–1862,” p. 1.

Ibid., pp. 5–6.

McCord, History of Columbiana County, Ohio and Representative Citizens, p. 150; Riles, “James Bennett, Pioneer Potter 1812–1862,” p. 7.

Gates and Ormerod, “The East Liverpool Pottery District,” p. 4. Bennett claimed in his later life that his was the first Rockingham ware in the United States, although the honor more likely goes to the Jersey City Pottery. John Ramsay, American Potters and Pottery (New York, N.Y.: Tudor Publishing Co., 1947), pp. 74–75.

McCord, History of Columbiana County, Ohio and Representative Citizens, pp. 150–51.

Ibid., p. 151.

Douglass C. North, The Economic Growth of the United States, 1790–1860 (New York and London: W.W. Norton and Company, 1966), pp. 202–4; Barth, History of Columbiana County, Ohio, p. 199.

Lura Woodside Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1950), p. 260.

Letter from Sarah Vodrey to John Vodrey, April 27 (private collection). The year is not given, but since John Vodrey died in May 1864 the letter probably was written in late 1863 or early 1864.

Burton Noble Gates, Boston Earthenware: Frederick Mear, Potter. Notes written for www.booklook.com/antref/ant25a.jpg (accessed May 1, 2004); John Gallo, Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Yellow Ware (Oneonta, N.Y.: J. Gallo, 1985), p. 32.

Barber, Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, p. 156.

Ibid.

W.A. Calhoun, “Early Clay Industries of the Upper Ohio Valley,” n.d., p. 36; manuscript on file at the Library of the Ohio Historical Society, Columbus, Ohio.

Barth, History of Columbiana County, Ohio, p. 199; Calhoun, “Early Clay Industries of the Upper Ohio Valley,” p. 37; Donna Juszczak, “The Legacy of the Mansion House” (manuscript on file at the East Liverpool Museum of Ceramics, n.d.), p. 1 ; East Liverpool Tribune, “Mansion and Union,” April 1, 1876, pp. 1–5.

Lucille T. Cox, “Early Inn Became Site of Local Potteries,” East Liverpool Review, October 27, 1938; “Mansion and Union,” East Liverpool Tribune, April 1, 1876, p. 1.

Cox, “Early Inn Became Site of Local Potteries.”

McCord, History of Columbiana County, Ohio and Representative Citizens, p. 151.

David Seekers, The Potteries (Merlins Bridge, Haverfordwest, England: C. I. Thomas and Son, 1981), p. 16.

Bernard Leach, A Potter’s Book (London: Faber and Faber Ltd., 1945), pp. 183–84.

“Mansion and Union,” April 1, 1876, p. 1.

Barber, Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, pp. 195–96.

McCord, History of Columbiana County, Ohio and Representative Citizens, p. 151.

Ramsay, American Potters and Pottery, pp. 31–52.

Gates, The City of Hills and Kilns, p. 40.

“Mansion and Union,” April 1, 1876, p. 2.

Cox, “Early Inn Became Site of Local Potteries.”

Calhoun, “Early Clay Industries of the Upper Ohio Valley,” p. 37.

“Mansion and Union,” April 1, 1876, p. 2.

Barth, History of Columbiana County, Ohio, p. 199; Calhoun, “Early Clay Industries of the Upper Ohio Valley,” p. 199; Cox, “Early Inn Became Site of Local Potteries.”

Barth, History of Columbiana County, Ohio, p. 199; Calhoun, “Early Clay Industries of the Upper Ohio Valley,” p. 37.

Gates and Ormerod, “The East Liverpool Pottery District,” p. 79.

Cox, “Early Inn Became Site of Local Potteries.”

Lucille T. Cox, “Talk of Depression, City Had Real One in ’54,” East Liverpool Review, March 6, 1939.

Ibid. Vouchers from the potteries were issued to pottery workers in lieu of wages. The pottery workers then cashed the vouchers at local stores for food and goods. The local store merchants accepted the pottery vouchers from the workers and in turn traveled to Pittsburgh where they stocked up on merchandise for their stores from wholesalers who accepted the pottery vouchers. The wholesalers then traveled to the potteries in East Liverpool where they cashed the vouchers for wares to wholesale in Pittsburgh. In this scenario, no cash transactions took place and still the workers got paid, the local stores and wholesalers made sales, and the potteries sustained their workforces in order to keep the market supplied with wares.

Gates and Ormerod, “The East Liverpool Pottery District,” p. 79.

“Mansion and Union,” April 1, 1876, p. 2.

Ibid.

Columbiana County Deed, Salt and Mear to Croxall and Cartwright, Deedbook 68, p. 230, on file at the Columbiana County Archives, Lisbon, Ohio.

Gates and Ormerod, “The East Liverpool Pottery District,” p. 38.

Ibid.

“Mansion and Union,” April 1, 1876, p. 5.

Ibid.

Croxall and Cartwright were rumored to have introduced the use of slate roofs for pottery buildings since slate was safer and could be had for the same price as wood. However, it cannot be confirmed that any of the buildings on the Mansion Pottery site had a slate roof, or that this building technique was reserved for the new buildings erected on their Union Pottery site located across Second Street. No slate was identified during the archaeological excavations at the Mansion Pottery, which suggests that it was not used there.

There were several East Liverpool potteries that produced doorknobs over the years: Godwin Pottery Company, from 1845 to 1849; Brunt Associations from 1850 to the 1930s; Harker Associations from 1848 to 1851; and Thomas China Company from 1873 to 1878. Gates and Ormerod, “The East Liverpool Pottery District,” pp. 18, 52, 79, 287.

Geoffrey A. Godden, British Pottery and Porcelain 1780–1850 (New York: A.S. Barnes and Company, 1939), pp. 43, 107.

Cox, “Early Inn Became Site of Local Potteries.”

Gates and Ormerod, “The East Liverpool Pottery District,” p. 38; Cox, “Early Inn Became Site of Local Potteries.”