Slat-back armchair, Delaware Valley, 1750–1780. Maple and hickory (microanalysis). H. 43", W. 24 7/8", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Banister-back side chair, attributed to Andrew Durand, probably Milford, Connecticut, 1740–1760. Maple and ash. H. 45 5/8", W. 19 1/8", D. 14". (Courtesy, New Haven Colony Historical Society, New Haven, Connecticut; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Fiddle-back armchair, eastern Connecticut, possibly New London County, 1765–1795. Maple and ash. H. 43 1/8", W. 23", D. 17". (Courtesy, Museum of Our National Heritage, Lexington, Massachusetts; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

High-back Windsor armchair, Philadelphia, ca. 1765. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple, oak, and hickory. H. 44 5/8", W. 25 3/8", D. 16". (Mr. and Mrs. James Palmer Flowers collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Low-back Windsor armchair, Philadelphia, ca. 1755–1762. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple, oak, and hickory. H. 28 1/8", W. 28", D. 16 5/8". (Mr. and Mrs. Joseph A. McFalls collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

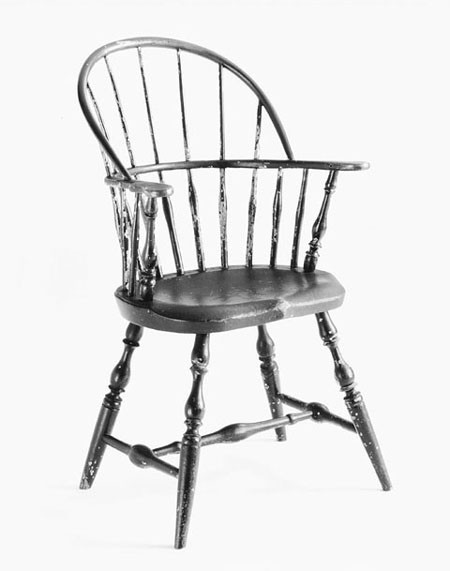

Sack-back Windsor armchair, Amos Denison Allen, South Windham, Connecticut, ca. 1796–1800. Chestnut (seat) with maple and oak (microanalysis). H. 36 1/8", W. 22 3/4", D. 15 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Fan-back Windsor side chair, Francis Trumble, Philadelphia, ca. 1778–1785. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple, black walnut, oak, and hickory (microanalysis). H. 35 3/4", W. 23 1/2", D. 19 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail of right crest terminal of the chair illustrated in fig. 7.

Bow-back Windsor armchair and side chair, Joseph Henzey, Philadelphia, 1785–1790. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple, oak, hickory, and ash (microanalysis). (Left to right) H. 37 5/8", 36 7/8"; W. 20 1/2", 17 5/8"; D. 17 3/4", 16". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Continuous-bow Windsor armchair, Walter MacBride, New York City, ca. 1792–1796. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple and oak (microanalysis). H. 37 5/8", W. 25 1/2", D. 17 3/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

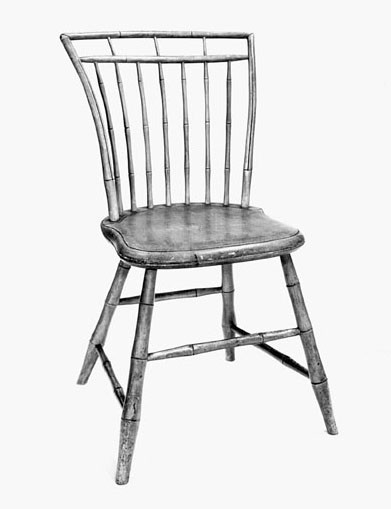

Square-back Windsor side chair with double bows, Jared Chesnut, Wilmington, Delaware, ca. 1804–1810. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple, walnut, oak, and hickory (microanalysis). H. 33 7/8", W. 18 1/4", D. 16 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Square-back Windsor side chair with double bows, Daniel Abbot and Company, Newburyport, Massachusetts, ca. 1809–1811. White pine (seat). H. 33", W. 19 3/8", D. 17 3/8". (Courtesy, Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, gift of Mrs. Arthur M. Merriam.)

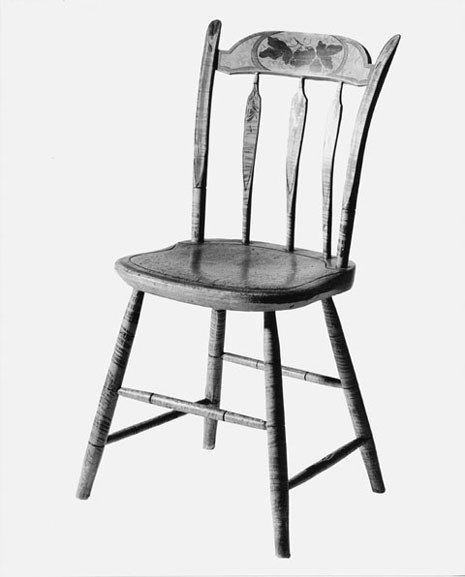

Slat-back Windsor side chair, New York City, ca. 1809–1815. Yellow poplar (seat). H. 34 3/4", W. 16 3/8", D. 14 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Slat-back Windsor side chair, eastern Massachusetts, possibly Worcester County, 1820–1830. White pine (seat). H. 34", W. 17 1/2", D. 16 1/4". (Courtesy, New Hampshire Historical Society, Concord; photo, Heritage Plantation of Sandwich, Sandwich, Massachusetts.)

Slat-back Windsor side chair, eastern Massachusetts, possibly Worcester County, 1820–1830. White pine (seat). H. 34 1/8", W. 17 3/8", D. 15 1/4". (Courtesy, John Tarrant Kenny Hitchcock Museum, Riverton, Connecticut; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

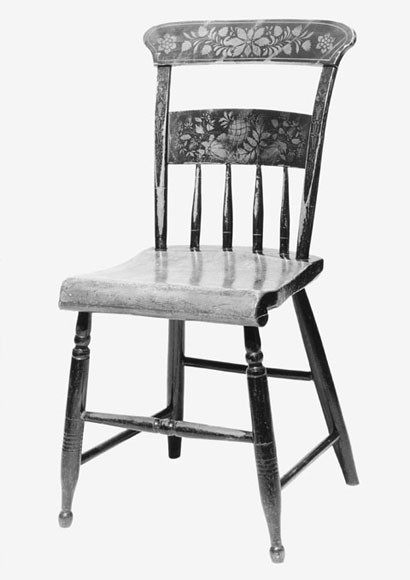

Triple-back Windsor side chair, Joel Pratt, Jr., Sterling, Massachusetts, 1820–1835. White pine (seat). H. 33 3/8", W. 17", D. 15 7/8". (Courtesy, Old Sturbridge Village, Sturbridge, Massachusetts; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Roll-top Windsor side chair with raised seat, John D. Pratt, Lunenburg, Massachusetts, ca. 1835–1840. White pine (seat). H. 34 5/8", W. 16 7/8", D. 15 1/2". (Carrie and Raymond Ruggles collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Tablet-top Windsor side chair with scroll seat, central Vermont, 1840–1850. White pine (seat). H. 33", W. 17 7/8", D. 14 5/8". (Courtesy, State of Vermont, Division for Historic Preservation, Old Constitution House, Windsor; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

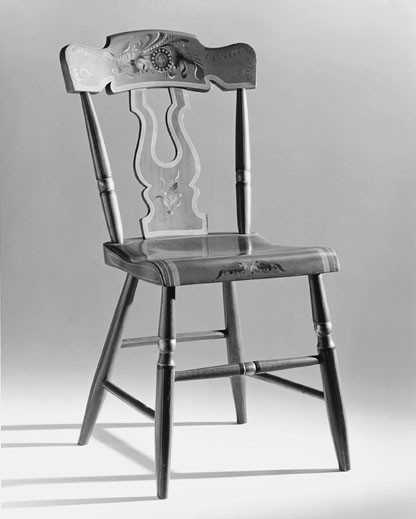

Tablet-top Windsor side chair with banister, central Pennsylvania, 1850–1860. Yellow poplar (seat). H. 34 1/8", W. 18 1/4", D. 15 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

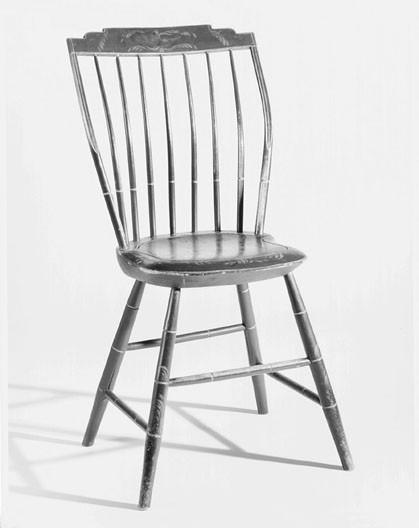

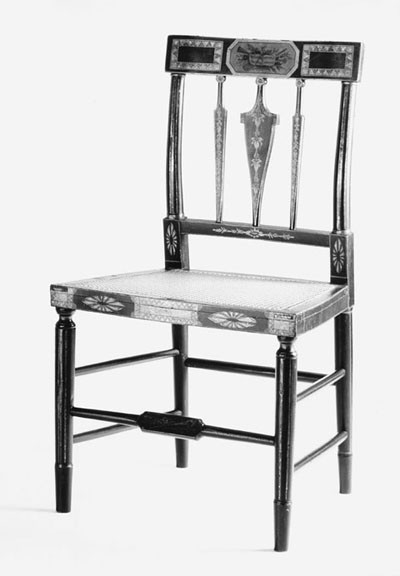

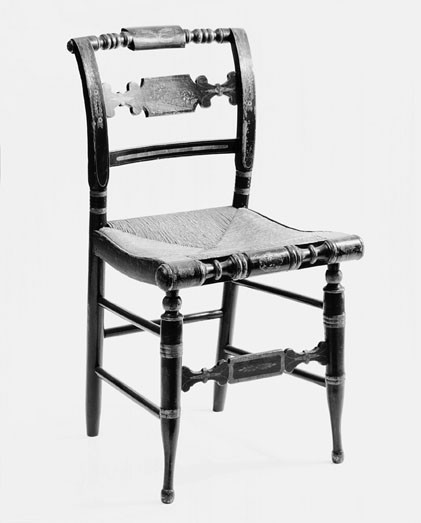

Tablet-top fancy side chair, Baltimore, Maryland, 1804–1814. Maple, yellow poplar, and mahogany (microanalysis). H. 33 3/4", W. 19", D. 15". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

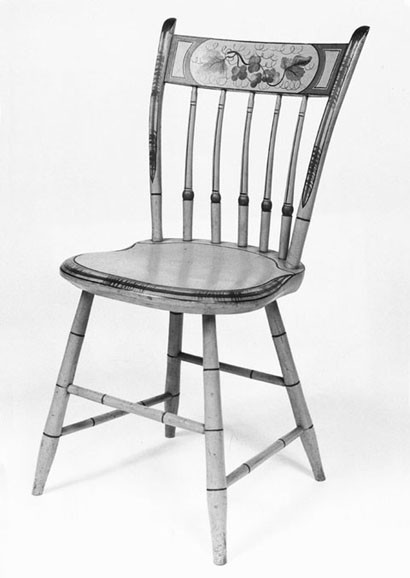

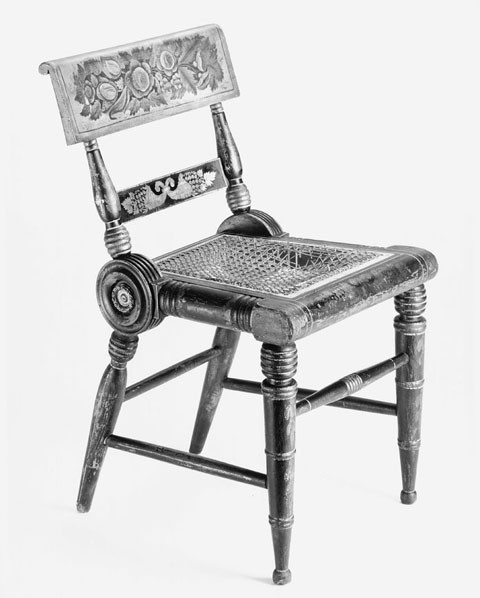

Spindle-back fancy side chair with Cumberland spindles, New York City, 1800–1815. Maple, birch, and yellow poplar (microanalysis). H. 35", W. 19", D. 15 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Spindle-back fancy armchair and side chair with organ spindles, New York City, 1810–1822. Woods and dimensions unknown. (Courtesy, Old Sturbridge Village; photo, Henry E. Peach.)

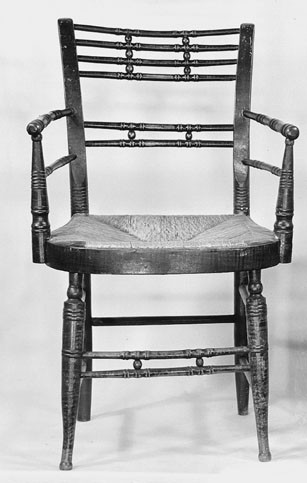

Ball-back bamboo fancy armchair, New York City, 1810–1820. Woods and dimensions unknown. (Courtesy, Old Sturbridge Village; photo, Henry E. Peach.)

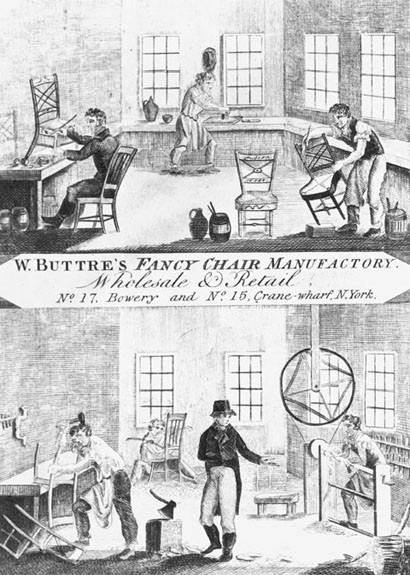

Detail of tradecard, William Buttre, New York City, ca. 1813. Engraving. 5 7/8" x 4 1/4" (overall image). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.)

Three-stick fancy side chair, Boston, Massachusetts, 1810–1822. Woods unknown. H. 33 1/4", W. 18 1/4", D. 16 1/8". (Courtesy, Collection of The American Folk Art Museum, New York, gift of the Historical Society of Early American Decoration; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

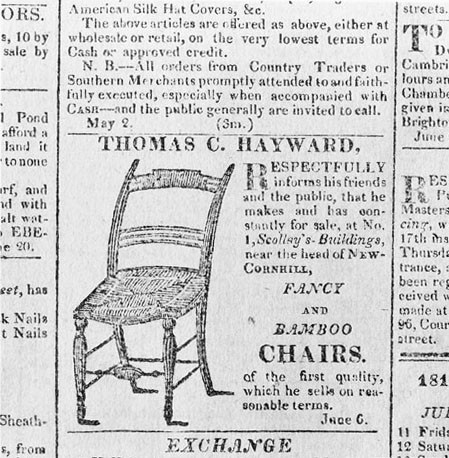

Advertisement, Thomas Cotton Hayward, New England Palladium and Commercial Advertiser, Boston, Massachusetts, July 11, 1819. (Courtesy, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

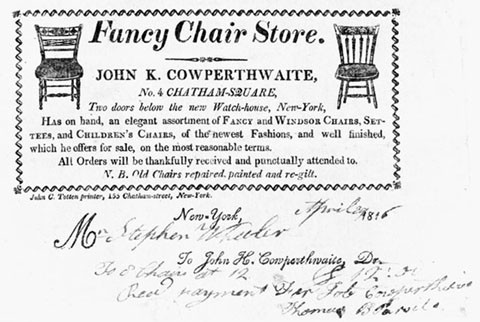

Billhead and bill, John Knox Cowperthwaite, New York City, printed ca. 1810–1812, inscribed 1816. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.)

Fret-back fancy armchair, New York City, 1816. Hickory, yellow poplar, maple, and ash. H. 33 7/8", W. 19 3/4", D. 16 1/8". (Courtesy, Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, gift of Gerrit van der Woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

Fret-back fancy armchair, Connecticut, 1815–1830. Woods unknown. H. 33 1/2", W. 18 3/4", D. 15 1/4". (Courtesy, Rhode Island Historical Society; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Fret-back fancy side chair, New York City, 1815–1830. Woods unknown. H. 33", W. 18", D. 15 1/2". (Former collection of I. M. Wiese; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Tablet-top fancy side chair (also “Circle Chair”), John R. Robinson, Baltimore, Maryland, 1829–1835. Woods unknown. H. 32 1/8", W. 19 1/2", D. 17". (Private collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Crown-top fancy side chair with frog back and turkey legs, Connecticut, 1830–1840. Woods unknown. H. 35 3/4", W. 17 3/4", D. 14 7/8". (Courtesy, Rhode Island Historical Society; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

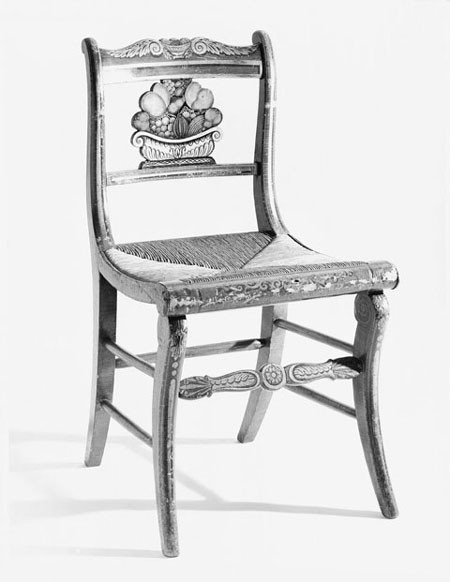

Grecian (or scroll-back) fancy side chair with scalloped top, possibly John W. Patterson, Philadelphia, 1830–1840. Yellow poplar, maple, and basswood (microanalysis). H. 32 1/2", W. 17 7/8", D. 16 3/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Terminology associated with vernacular seating furniture in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries can be variable, obscure, misleading, and above all confusing. Nomenclature changed with time, distance, and document. This study, based on an analysis of more than two hundred documents—account books and sheets, estate and insolvency records, family papers, shipping records, court records, and advertisements—explores the vocabulary of vernacular seating furniture in four categories: common woven-bottom chairs, Windsor chairs, fancy chairs, and chair stock. A certain amount of overlap occurs between and within the groups. During the period covered by this study, vernacular seating furniture was part of every American household as well as many businesses and institutions.

Common woven-bottom chairs were already a market fixture when colonial artisans at Philadelphia introduced the Windsor chair during the mid-1740s. By the 1780s the new form was on its way to dominating the vernacular market. The same decade marked the introduction of another seating form, the fancy chair. This elegant seat, which offered the customer variety in surface color and decoration, soon occupied a position at the high end of the trade and had a marked impact on the Windsor. Until then, verdigris green surfaces prevailed in Windsor seating. The fancy chair provided new directions in market appeal to which the Windsor chairmakers quickly responded. As a rule of thumb in identifying vernacular seating furniture in middle-class households of the 1790s, common chairs furnished the kitchen, Windsors occupied the dining room, and fancy chairs brightened the parlor.

This study draws heavily on New England craft records, because they survive in greater number than those of other regions. Samplings from Middle Atlantic locations, although fewer, adequately represent the work of craftsmen from New York to Maryland. Craft documents produced by southern craftsmen are uncommon.

Common Woven-Bottom Chairs

Common, kitchen, and slat-back chairs generally had similar elements (fig. 1). The difference lay in structure—number of back slats, extent of turned work—and surface embellishment, which ranged from the absence of finish to stained, colored (pigment in resin), and painted surfaces. A limited number of great chairs, or chairs with arms, and children’s chairs were also constructed with slats. The cross members in the back, often graduated in size from top to bottom, varied in profile from straight to arched, double-arched, elliptic, and truncated form. For purposes of reference and pricing, craftsmen frequently identified slat-back chairs by the number of cross members in the back. The price increased with the number of slats.

Solomon Fussell (d. 1762), a Philadelphia chairmaker, charged 4s apiece for “half doz 3 Slat Coloured Chairs” in 1738. His “best Six Slat Chairs” were priced at 6s 6d (1745). Armchairs cost more. The example illustrated in figure 1 has another feature that would have added to the price, a “turnd frunt,” or fancy stretcher. Fussell frequently purchased ready-formed chair parts from turning specialists. Itemized among this stock are chair lists, the shaved sticks that form the framework for weaving the rush seat. The chairmaker also recorded “Checkt bottoms” on occasion, identifying a woven material referred to today as splint.[1]

John Gaines II (1677–1748) and his son Thomas (1712–1761) of Ipswich, Massachusetts, were in business earlier than Fussell. They also made “slatted” chairs, which they sometimes referred to as “splatted” chairs. Color choices included black and brown. Another common term describing the slat-back chair appears in the accounts of David Haven (d. 1800/1801), who made and sold “three Back” and “Common 4 Back” chairs at Framingham, Massachusetts, at the end of the eighteenth century. Haven sold some of his chairs without the woven seats. Many chairs were stained or stained and varnished. References to “White Chairs” identify seating that was unpainted, or “in the wood” as they were often described in the trade. The “Chair stuff” Haven received from suppliers to frame his chairs consisted of “Long Posts” (vertical back members), “short Posts” (front legs with or without arm supports), “Backs” (slats), “Rounds” (stretchers), and “seatlists.”[2]

Banister-back chairs, like those with slat backs, were in the American furniture market early in the eighteenth century. Considerably more work marked their construction, and the price was proportionally higher. A number of New England examples have uncarved, intricately sawed crown tops. The example illustrated in figure 2 has been attributed to Andrew Durand (1702–1791) of Milford, Connecticut, whose sons John (1735–1780) and Samuel I (1738–1829) followed him in business. A chair attributed to the sons is close in form, aside from substituting an embowed slat for a crown. From an analysis of John’s accounts, it appears that this frame is what he described as a “black” chair. References to seating furniture by color rather than pattern are reasonably common in craftsmen’s records. The banister-back chair was a popular style in Connecticut and Rhode Island; but it was also made as far north as New Hampshire, where James Chase (1737–1812) of Gilmanton had a few lingering calls for the pattern at the turn of

the century.[3]

The terms york chair and fiddle-back chair seem in most instances to have identified the same pattern in the records of producers and consumers (fig. 3). When both words appear in the same record, as they do in the memorandum (order) book of Amos Denison Allen (1774–1855) and the account book of Samuel Durand I (both craftsmen from eastern Connecticut), they represent different periods of recordkeeping by each man. Because Durand’s entries record furniture sales, they are priced. The cost of york chairs and fiddle-back chairs was the same—6s apiece, or $1 in the new currency of the post-revolutionary period. Other records show that within either category the price could fluctuate, indicating that options were available in terms of structural and surface embellishment. At the shop of Elisha Hawley (1759–1850) in Ridgefield, Connecticut, “fiddle Back Chairs” cost anywhere from 5s to 7s 10d apiece. One group of 7s chairs identified as “green” appears to have been painted instead of colored, stained, or coated with cheaper paint colors, such as black or brown. Half a dozen chairs constituted a set.[4]

Although the term york chair is found in coastal Connecticut and Rhode Island records, its use there is less frequent than fiddle-back chair. A distinctive rush-seat chair, framed with a yoke crest, splat back, and front legs of conical form ending in pad feet, was popular in New York City and its satellite regions (northern New Jersey, Long Island, and the Hudson Valley) from the 1750s through the end of the century. Several are documented with makers’ stamps. This New York pattern seems to have given rise to the sobriquet york chair along the northern coast of Long Island Sound. A few yoke-top Connecticut chairs are made with heavy New York pad-foot legs, but more are turned with embellished cylindrical legs (fig. 3). In New York fiddle-back is presumed to have been the common term for yoke-top, splat-back seating, in view of James Chestney’s (d. 1862) use of this term in 1797 at Albany in a newspaper advertisement that illustrates this type of chair.[5]

Windsor Chairs: The 1740s to 1799

The nomenclature of eighteenth-century Windsor furniture is relatively straightforward, because the number of patterns introduced to the market was limited in contrast to the activity in the nineteenth century. Windsor chair was the generic name for all patterns of this construction, although the term often specifically distinguished the armchair from the side chair in references itemizing mixed forms.

The first pattern in the market was designated a high-back chair because of its tall structure (fig. 4). Today that term has been obscured by the popularity of the late nineteenth-century appellation comb-back chair, which refers to the top piece. The high-back Windsor was anything but a poor man’s chair. Priced between 14s and 18s at Philadelphia in the quarter century before the Revolution, the cost equaled that of about three-days’ wages for an average tradesman. Many of the purchasers were merchants who retained some chairs for personal use and shipped others to clients. An important coastal market was Charleston, South Carolina, where merchants Sheed and White advertised “high backed” Windsors among their stock in 1766. New York was another prewar market. When the wealthy Quaker merchant Walter Franklin died about 1780, his executors listed five high-back Windsors in the household.[6]

Newport, Rhode Island, chairmakers also produced tall Windsor chairs before and after the Revolution. Some were for domestic use; others furnished public institutions, such as the green chairs purchased for the Newport County courthouse in 1784, among which was one described as “Large with high back.” Green high-back Windsors comprised part of the furniture cargoes that Aaron Lopez, a Newport merchant, shipped regularly to southern coastal and tropical markets during the 1760s. Verdigris green was, in fact, the common color of all American Windsor seating until after the Revolution, giving rise everywhere to the appellation green chairs. Stephen Girard, a merchant prince of Philadelphia, included a category in his accounting system for “Green Chairs” as late as 1787. Philadelphia chair was a term that recognized the principal center of Windsor production in the eighteenth century. The estate of Isaac Smith, a Boston merchant, contained a “large Philadelphia Chair” in 1787.[7]

By the 1780s the high-back chair had been in the market for three decades. A slimmer version with a circular seat introduced at Philadelphia in the 1760s is sometimes referred to in documents as a small high-back chair. After the Revolution, chairmakers substituted an oval seat and exchanged the ball feet for tapered legs. By then tall chairs were being made in New England. A type particularly sought today by collectors is one associated with Nantucket Island that has a decided cant to the back and is frequently fitted with braces—a pair of spindles mounted in an extension at the seat back. Island inventories describe the nomenclature: “Large Green Chair,” “high Back Green Chair,” “Great Green Chair,” “Mans high Back Chair,” and “high wooden bottom Chair.” The last phrase focuses on the critical unit of construction in the Windsor, the plank seat.[8]

Sheed and White also offered Philadelphia low-back chairs for sale at Charleston in 1766 (fig. 5). A rare document dated in 1762 and acknowledging the receipt of £4.10 for six chairs of this pattern from Philadelphia businessman Garrett Meade is signed by Thomas Gilpin (fl. 1752–1767). Gilpin, who first made Windsor chairs in the 1750s, produced the earliest known documented examples (branded). Aaron Lopez of Newport recorded an alternative term for the low-back Windsor when he shipped “12 Round Green Chairs” to a tropical port in 1767. The term round is significant yet ambiguous. Clarification occurs a year later in an invoice regarding furniture shipped to Maryland, which lists “10 round back straw bottom’d Chairs” and “4 round back wooden bottom Green Chairs.” The straw- or rush-bottom chairs were roundabouts, produced as either vernacular or joined seating in the eighteenth century. The low Windsor duplicates the circular profile of the arm rail.[9]

Although the low-back chair is the rarest of all Windsor patterns, probate records identify its broad distribution in households of Boston, Nantucket, Newport, New York, and Philadelphia. In 1779 appraisers at Newport identified “green round about Chairs” in Nicholas Lechmere’s confiscated Tory estate. Six low-back Windsors complemented the five high ones in Walter Franklin’s household at New York, and at Philadelphia, widow Rebecca Seaton enjoyed the comfort of a cushion with her low-back Windsor.[10]

Philadelphia chairmakers introduced the sack-back chair to the market during the early 1760s. Although craftsmen eventually made this chair in greater numbers than high-back and low-back chairs, the pattern never achieved the popularity in Philadelphia or the Middle Atlantic region that it attained in New England (fig. 6).

The first mention of the pattern appears to be in a notice by Andrew Gautier, a New York shopkeeper who imported and sold Philadelphia Windsor chairs as early as 1765. By the 1770s several terms supplemented sack-back to identify the armchair framed with a bow enclosing the spindle tops.[11]

Francis Trumble (ca. 1716–1798) of Philadelphia described “arch top” chairs in 1770 priced at 15s apiece. A year later he delivered a dozen similarly priced chairs to John Cadwalader, identifying them as “round top” Windsors. The term appeared again a few years later when Uriah Woolman shipped twenty-four chairs and other cargo to Charleston, South Carolina, where dealers were already advertising chairs of this description. Trumble provided further insights into nomenclature when he billed Isaac Hazlehurst and Company in 1789 for a large order of eight dozen chairs, placed on board the ship Canton bound for the Far East. Among the patterns listed are “Scroled Arm [Chairs]” and “Plain Armed D[itt]o.” The prices were somewhat lower than earlier. A sack-back, or round-top, chair with plain arms is illustrated in figure 6. The scroll arms are terminated by small, carved knuckles, formed by attaching extra pieces of shaped wood to the lower surface of the tips.[12]

The nomenclature for the sack-back chair took a different turn in eastern Connecticut, where the work of Amos Denison Allen is identified by branded examples (fig. 6) and by orders recorded in his memorandum book. Only careful analysis of the orders and prior knowledge of Allen’s production, however, identify his “armed Chairs @ 9/4 each” as sack-back Windsors. The term Windsor never appears in his records. In neighboring Scotland, Connecticut, Judge Ebenezer Devotion acquired “arm Chairs” from nearby chairmakers Theodosius Parsons (fl. 1784–1799) and Ebenezer Tracy, Sr. (1744–1803). The records of Solomon Cole (1772–1870), who worked in Glastonbury, south of Hartford, are somewhat more comprehensive than those of Allen. The price range for his “arm d Chair,” which he produced from 1795 to 1807, was broad, ranging from 6s to 10s 6d. Cole framed one chair with rockers and charged 11s. Yellow and green are mentioned as finish colors.[13]

Production of the fan-back Windsor, the first side chair in the market, reached its stride following the Revolution (fig. 7). Market acceptance of the chair can be measured in the proliferation of Windsor records in the postwar period and their initial focus on this pattern. The Windsor side chair offered consumers greater flexibility in furnishing and more attractive prices. Philadelphia customers had two options: a “plain” (also “common”) pattern or a “Scrowl top” one. Carved crest terminals embellished the second pattern (fig. 8), and about one shilling separated the two in price. Fan-back Windsors were available from the leading Philadelphia chairmakers—William Cox (d. 1811), Joseph Henzey, Sr. (1743–1796), and Francis Trumble—as well as from “workmen whose names [were] less up.” At his untimely death in 1793, John Lambert owned a supply of chair parts used in constructing fan-back Windsors: “Chair Bottoms made” (finished seats), “Stretchers,” “Sticks” (spindles), and “30 Fan Back top Rails bent.” A decade later, “50 fan back Chairs partly finished” stood in the shop of Ansel Goodrich (ca. 1773–1803) at Northampton, Massachusetts, when the chairmaker died suddenly at age thirty.[14]

The fan-back Windsor was the first in a long line of plank-seat side chairs employed for dining. In 1785 when a member of the Coates family of Philadelphia purchased “Six Scrowl Top Dining Chairs” from Joseph Henzey, the practice was already established. The word dining serves a dual role here as a synonym for Windsor and as a window on function. Outside the dining room, fan-back chairs furnished ships’ cabins, inns, resort hotels, a theater in Boston, and the premises of a dancing master in Portland, Maine. The chair remained a salable product well into the nineteenth century, especially in New England. In 1811 appraisers itemized seven fan-back chairs with the contents of Ebenezer Knowlton’s (ca. 1769–1810) woodworking shop in Boston. Connecticut chairmakers Oliver Avery (1757–1842) of North Stonington and Samuel Douglas (d. 1845) of Canton recorded sales of fan-back chairs in 1813 and 1816, respectively.[15]

About 1785 the chairmaking community at Philadelphia introduced a second Windsor side chair to the American furniture market, this one with a rounded back (fig. 9). Evidence of its early fabrication in city shops occurs in the receipt book of Robert Blackwell, who purchased “8 ovel-back Chairs” for £4 from John Letchworth (1759–1843) in 1787. Outside Philadelphia the chair was better known as a bow-back Windsor. For the first time a Windsor side chair and a companion armchair were designed en suite. A substantial change in the turned work of the base introduced simulated bamboo elements at Philadelphia (the baluster leg was retained some years longer in other locations). The average local price of the side chair at 11s 3d, up several shillings from the cost of the fan-back chair, reflected the newly fashionable status of the pattern in the urban center.[16]

The redesigned turnings of the bow-back Windsor gave rise to another name frequently associated with this pattern, that of bamboo chair, although the term was more common after 1800 to describe a later style. One of the popular painted surfaces for the bow-back chair was pale yellow, or “straw” color, one that simulated the natural material. White, green, and mahogany were other color choices, and purchasers of armchairs had the option of choosing real or painted mahogany arms, as indicated in Stephen Girard’s order to Joseph Henzey for “Bamboo windsor Chairs with mohogny arms” priced at 18s 9d apiece. Short resting pieces attached to the back frame of the chair were referred to as “elbows.” Thirty-three were enumerated in John Lambert’s shop inventory (1793), along with modish “Turned Bamboo Feet” and “Turnd Bamboo Sticks.” Together the Lambert and Trumble (1798) inventories describe the primary element of the rounded chair back in three stages of production: “Bowes for Chairs (in the Ruff)” (Trumble), “Long Bows cleaned up,” and “Long Bows bent” (Lambert).[17]

Other variations in nomenclature relative to the bow-back chair can be noted outside Pennsylvania. Amos Denison Allen of Connecticut consistently identified the bow-back form as a “Dining Chair” in his memorandum book, again providing a focus on function rather than form. Of the two styles of eighteenth-century Windsor side chairs, the bow-back chair was the more satisfactory design for use around a table because it had no protruding top piece.[18]

Given the profile of the bow-back Windsor, the word round again figures in descriptions, although records do not always distinguish clearly between this chair and the sack-back chair. Cost and numbers can provide clues. The unit price of six “Round Chairs” (bow-backs) framed in 1790 at Salem, Massachusetts, by Josiah Austin (1746–1825) was 7s 6d. Another local shop priced two “round top,” or sack-back, armchairs at 10s a few years later. In upstate New York, Elihu Alvord (1775–1863) of Ballston Springs supplied “101 round back windsor Chairs” for Nicholas Low’s Sans Souci Hotel in 1804, charging 7s 6d apiece, the same as Austin. A year later Hector Sanford (1780–1837) offered round-back chairs and newer eastern styles to customers in Chillicothe, Ohio.[19]

The most elusive Windsor pattern to track in records is the one developed about 1790 in New York City and known today as a continuous-bow chair (fig. 10). Although New York moved rapidly during the 1790s toward premier status among American seaports, and her chairmakers engaged in a productive commerce in seating furniture, few local craft records exist for this period. A 1792 bill from chairmaker Peter Tillou (fl. 1765-1798) to a Mrs. Montgomery lists “12 New Fashion Painted chairs” priced at 9s 6d apiece. The price may identify armchairs, but the bow-back chair was also a relatively new pattern in the market at this date. More positive evidence of the chair exists outside the city.[20]

Following New York’s lead, craftsmen in Connecticut and Rhode Island also produced continuous-bow chairs. A notation dated 1793 in the account book of Elisha Hawley of Ridgefield, Connecticut, appears to identify this pattern: “To Winsor Chair three boss [bows].” An uncommon triple-back chair seems implied, but in fact the bows probably were bends—one at the top and two forming the arms. The price was 9s. Continuous-bow chairs with family histories are still owned locally.[21]

The best information about production of the continuous-bow chair comes from the shop records of Amos Denison Allen of South Windham, Connecticut. Again, only careful analysis of Allen’s memorandum book and knowledge of his documented Windsor work permits identification of his “fancy” chair as the pattern in question. The price was about the same as that for his sack-back chair; Windsor side chairs were one to two shillings cheaper. When Allen started making continuous-bow chairs in 1797, the backs were strengthened with a pair of extra spindles anchored in a rear extension of the seat, as illustrated in figure 10. Only later did the craftsman make special note of “Fancy Chs without braces.” Customers chose green, yellow, blue, or red (brownish) painted surfaces. A few chairs, probably those in the bamboo style only, were ornamented with narrow stripes. Based on recorded orders, Allen’s customers paired their continuous-bow chairs with both fan-back and bow-back side chairs.[22]

Windsor Chairs: 1800 to 1850

When Robert Taylor and Daniel King (fl. 1799–1800) of Philadelphia billed Stephen Girard for “1 Doz Newfashiond Wite Dining Chairs” at $2 apiece on May 21, 1799, the chairmakers identified a second bamboo-framed Windsor pattern introduced to the American chairmaking community at Philadelphia (fig. 11). Local artisans fitted the new chair with a squared back in place of the round one that had been in the market for over a decade. The new design was commonly referred to everywhere as a bamboo Windsor, and it was still a marketable product in 1810 when Joseph Burden (fl. 1791–1837) supplied a dozen chairs to Girard for his flourishing export trade. At Wilmington, Delaware, a short distance down the Delaware River from Philadelphia, merchant James Brobson shipped “Six doz’n Bamboo Chairs” to Barbados in 1804. Jared Chesnut (fl. 1800–1837), a local chairmaker, could have been the supplier (fig. 11).[23]

As early as 1801 David Alling (1773–1855) purchased “Bamboo Stuff” from suppliers for his nascent, although already flourishing, chairmaking enterprise at Newark, New Jersey, across the bay from New York City. He finished some chair seats with rush, and others with cane, but his wood-seat “Windsor Bamboo” was also a viable product for more than a decade. Allen Holcomb (1782–1860), a New Englander who migrated to upstate New York via Troy in the early nineteenth century, produced sets of “Bamboo Dining Chairs,” a reminder that the Windsor side chair in its successive patterns through the mid-nineteenth century occupied a principal position in the American dining room.[24]

Craftsmen throughout New England framed bamboo chairs, a term that remained common into the 1820s, although alternative names describe similar products. Square-back, or square-top, chair is a generic appellation that identifies most Windsor styles from 1800 to 1850. When used by Solomon Cole of Connecticut in 1806–1807, “square top” described chairs “with double bows” much like that in figure 12. The pattern is a variation of figure 11, with alternate spindles piercing the lower cross rod (“bow”) of the crest. Cole’s side chairs were priced at 9s equaling $1.50. Silas E. Cheney’s (1776–1821) comparable “square Back Chairs” cost $1.33 if “plain” and $1.50 when “ornimented.” He also framed a companion armchair at his shop in Litchfield, Connecticut.[25]

The identification of slim top pieces as “bows” was also common practice outside New England. Charles C. Robinson (d. 1825) of Philadelphia made chairs with “Double Bows” and “Single Bows.” The word bow derives from the lateral bend of the cross rods, which complements the curve at the back of the seat. When distinguishing between back pieces for square-back chairs and oval-back chairs, appraisers of Henry Prall’s (d. 1802) estate identified “Longe Bows” and “short Bows.” Thomas Adams’s (fl. 1797–1855) bill for furniture made for the U.S. War Department at Washington in 1814 lists a variant of the term as “1 Dozen Chairs Single Tops” priced at $1.50 apiece.[26]

Early nineteenth-century craftsmen also distinguished between chairs with straight backs (fig. 11) and bent backs (fig. 12), a practice that continued well into the century. The nomenclature differentiates straight back posts socketed into the seat at a slight cant from posts steamed and bent before socketing, although neither term identifies the actual crest pattern. Both back forms had a broad geographic distribution. Straight-back chairs appear in the records of craftsmen as widely separated as Thomas Boynton (1786–1849) of Windsor, Vermont, William Beesley (1797–1842) of Salem, New Jersey, and Caleb Gallup (d. 1827) of Norwalk, Ohio.[27]

Bent-back chairs are mentioned more frequently in records than straight-back chairs, probably because they represent a variation from standard framing practice. The added labor of bending the backs also made them more costly. In 1819 David Alling of Newark, New Jersey, shipped two dozen each of yellow and green “winsor bent backs” to New Orleans. In upstate New York bent-back chairs and bedstead posts were part of a barter arrangement in which Allen Holcomb of Otsego County received a clock case in exchange. In New England Thomas Boynton made bent-back chairs in Boston before he relocated to Hartland–Windsor, Vermont, in 1811–1812. In Vermont his bent-back production included, appropriately, “single top” and “Double top” Windsors. Elizur Barnes (1780–1825) of Middletown, Connecticut, framed “Bent Back Wood Seat” chairs a few years later. Eastern patterns were available at many “western” locations shortly after their introduction. In 1816 Henry May and Thomas S. Renshaw (fl. 1816 to ca. 1818) advertised bent-back chairs at Chillicothe, Ohio.[28]

Other terms also describe the bent-back chair. Spring-back (or “sprung-back”) was used by Bernard Foot (fl. 1813–1818) at Newburyport, Massachusetts, and by David Pritchard (1775–1838) and Silas Cheney in Connecticut. A receipted bill signed by Isaac Stone (b. 1767) at Salem, Massachusetts, in 1811 identifies “Fallback Bamboo Chairs.” The records of David Pritchard focus on a term that describes another feature of the early nineteenth-century bamboo chair. Between 1804 and 1807 he sold sets of “miter-top” chairs from his Waterbury, Connecticut, shop. The side chair shown in figure 12 has the “miter,” or diagonal groove, at the junctures of the top rail and back posts. The joints are actually round tenons and mortises located below the miters. The grooves in bamboo-style chairs are aptly described as “creases” in the shop inventory of Anthony Steel (d. 1817) of Philadelphia. The 1817 document lists “creased” stock consisting of “sticks” (spindles), “elbows” (arms), “feet” (legs), and “stretchers.”[29]

A crest pattern that was extraordinarily popular in New England during the 1810s is difficult to track in contemporary records (fig. 13). The profile of the top piece imitates that of joined chairs introduced by cabinetmakers in Boston about the turn of the century. A paucity of records by local craftsmen during this period may account for the lack of good information, and the pattern also may have been known by more than one name.

A document that appears to throw light on the subject is the probate inventory of cabinetmaker Benjamin Bass (fl. 1798–1819), who died at Boston in 1819. The enumeration, which lists both formal and vernacular seating furniture, names several patterns, among them “Tablet Chairs wooden bottoms.” Prices are in the same range as Bass’s “Bamboo Chairs” at $1.25 to $1.50 apiece. Tablet-top chairs were framed with the crest tenoned to the top of the back posts. With its bulging uprights flanking the spindles, the chair illustrated in figure 13 may be a variant type that Henry Beck (1787–1837) of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, called a “swell back;” or, that term may simply describe a bent-back chair. Between 1812 and 1814, Thomas Boynton, who had only recently removed from Boston to Vermont, identified one of the chairs he produced at his “manufactory” at Hartland-Windsor as a “fancy top Bb [bent back] Chair.” He priced it at $2. The term “fancy” was a general one used throughout the early nineteenth century to describe several top pieces, each uncommon, or special, in its pattern or variation.[30]

The alternative in nineteenth-century Windsor construction to framing the crest on top of the back posts was to place the back piece between the posts (fig. 14). The basic pattern is referred to as a slat-back Windsor in period documents. The style, introduced in New York and New England before 1810 and slightly later in other areas, remained popular into the 1840s. Both straight and bent profiles were available. In the earliest patterns, creased cylindrical spindles accompany a plain rectangular slat. Slats were also referred to as benders because of their lateral curve. David Alling paid a journeyman $4.50 in 1816 to paint and ornament “24 Windsor Slat Backs” whose upper structure was framed in the general pattern of the chair shown in figure 14. Alling was a considerable supplier of the New York furniture market.[31]

During the 1820s the spindle count in slat-back chairs was reduced from six or seven to four or five, and the terms four-rod and five-rod chair came into use (fig. 15). Thomas Walter Ward II stocked both styles at his store in Pomfret, Connecticut, in the 1830s. Jacob Felton (1787–1864) of Fitzwilliam, New Hampshire, supplied the Boston market, and Elbridge Gerry Reed (1800–1870) of Sterling, Massachusetts, framed hundreds of rod-style slat backs for fellow chairmakers in Worcester County. At Hartford, Connecticut, Philemon Robbins (fl. 1833–1870s) acquired his four- and five-rod chair stock from Sullivan Hill (b. 1808), a supplier in Spencer, Massachusetts. The wholesale price of five-rod chairs was 121/2 percent higher than that of four-rod chairs because of the extra labor. When Robbins retailed the chairs, the markup was 40 to 47 percent greater than the wholesale cost.[32]

Many four- and five-rod chairs were framed with ball-turned spindles, which gave rise to the term ball-back chair (fig. 15). The choice of pattern name was a matter of local preference. A word of caution is in order, however. A ball-back chair could be framed with horizontal sticks and balls rather than vertical members. Many chairs of the second type had rush or cane seats instead of wooden bottoms. Crossover terminology between Windsor and fancy seating is thus a factor to be reckoned with in interpretation. In 1825 Elizur Barnes of Middletown, Connecticut, specifically identified stock framed in his shop as “Ball Back Wood Seet Cheirs.” Another time he described the same seating as “ballback winsor.” Ball-back chairs with vertical sticks were produced for several decades. In 1842 at a sale disposing of part of the estate of chairmaker Peter A. Willard (fl. 1824–1842) of Sterling, Massachusetts, quantities of “Balld Rods” were sold at 20¢ and 25¢ per hundred. Similar stock was offered the same year at Philadelphia in the estate of Charles Riley (fl. 1813–1842).[33]

The method of framing a slat-style crest piece between the back posts produced yet another term identifying a Windsor: mortise-top. “6 Yellow mortised-top Chairs” stood in the “West Chamber” of the home of Peter A. Willard at Sterling, Massachusetts, in 1842. The shop records of fellow Worcester County chairmaker Elbridge Gerry Reed indicate that he framed thousands of mortise-top chairs for area entrepreneurs. Sometimes Reed had to bend “the stuff” first. His pay for framing mortise-top chairs ranged from under 10¢ per chair to as much as 25¢, an indication that patterns more complicated than the simple spindle styles were involved.[34]

A variant pattern in mortise-top construction introduced a loaf-shape slat and arrow-shape spindles to the Windsor chair back (fig. 16). Neither term is contemporary with the period, however. Windsors with this crest may have been referred to as “Round Top Chairs,” a term used at Waterbury, Connecticut, in 1839 by appraisers of the estate of chairmaker David Pritchard. Another candidate is fancy-top, a term mentioned in the correspondence of Joel Pratt, Jr. (1789–1868), of Sterling, Massachusetts. During the mid-1840s, Calvin Stetson (d. ca. 1860) of Barnstable on Cape Cod retailed fancy-top chairs received from his Boston supplier, William P. Haley (fl. 1837–1859). Some are described as painted a dark color.[35]

Appraisers who inventoried Anthony Steel’s estate at Philadelphia in 1817 identified broad spindles of the type shown in figure 16 as “flat Sticks.” The profile is actually a slimmed down neoclassical urn, adapted first for use in fancy seating. During the 1810s the shaped stick became a feature in some high-quality Windsors. The Steel inventory also lists “chair stumps,” or posts, along with “elbows” (arms). The records of Joel Pratt, Jr., and Elbridge Gerry Reed of Massachusetts introduce substitute terms for the heavy uprights in chair backs and arms. The preferred name in Worcester County was pillar, although on occasion Reed referred to standards. Armchairs are uncommon in nineteenth-century Windsor work, however. The bread-and-butter seating form of the trade was the side chair.[36]

The chair illustrated in figure 16 is notable for another feature. Its surface is painted to resemble maple. Both the random striping and raw sienna color, varying from light yellowish brown for the ground to medium shades for the streaking, reinforce that image. Chairs with surfaces “which are imitations of various kinds of Wood, such as Rose Wood, Sattin Wood, Hair [sic] Wood, Maple Wood, &c.” were advertised in 1815 by William Haydon (fl. 1799–1833) of Philadelphia, although the period of their greatest popularity came later. W. A. and D. M. Coggeshall (fl. 1835–1845) of Newport, Rhode Island, retailed “Imitation Maple” chairs of various patterns in 1835, several years before A. and J. B. Mathiot (fl. 1840–1851) offered chairs in “a variety of imitation wood colors” at their “GAY STREET CHAIR WARE ROOMS” in Baltimore.[37]

Double-back and triple-back Windsors were other staples of the eastern Massachusetts chair trade that fall into the general category of mortise-top chairs (fig. 17). The extra work of preparing mortise holes in the posts to receive the crosspieces at midback would have placed the chairs, especially the triple-back pattern, toward the upper range of Elbridge Gerry Reed’s labor charge for framing mortise-top chairs. Collectively, the crosspieces of the upper structure, whether narrow or broad, were referred to as “Backs” in the account book of Joel Pratt, Jr., of Sterling. That record lists thousands of chair parts, including “Rods,” received from suppliers. Although sizes are omitted, short, ball-turned sticks, such as those illustrated in figure 17, would have been included with the rods.[38]

By the second quarter of the nineteenth century the chair trade in eastern Massachusetts and adjacent areas provided employment for hundreds of individuals—suppliers of chair stock, framers, ornamental painters, and retailers. Many more found jobs in support capacities as teamsters and suppliers of raw materials. Vast quantities of framed chairs were retailed and wholesaled throughout the region and funneled into Boston and other urban centers for broader distribution. Josiah Prescott Wilder (1801–1873) and Jacob Felton produced chairs in southern New Hampshire. Wilder’s principal market was Lowell, a rising textile manufacturing center on the Merrimack River northwest of Boston. Felton sent chairs east to Boston and west to Brattleboro, Vermont, on the Connecticut River. One of his products was the “square front [seat] Doubl back” chair. Elbridge Gerry Reed and Samuel Stuart (d. 1829) were substantial chairmakers in Worcester County. In 1829 “1 hundred triple back chairs” stood in Stuart’s shop ready to be transported to a large market such as Boston in his “one horse wagon & chair rack.”[39]

Luke Houghton (d. 1877) of Barre, Massachusetts, purchased his stock and distributed his “duble back chairs” in a localized market that encompassed about a dozen towns in Worcester County. Other central Massachusetts craftsmen supplied chairs for Philemon Robbins’s retail establishment in Hartford. At Norwich near the coast in 1830, the partners Congdon and Tracy (fl. 1830–1831) advertised “1000 chairs Just received from one of the best manufactories in New England.” Their stock included both “double back” and “five rodded” chairs in “light and dark” colors.[40]

For three decades, from the 1820s through the 1840s, New York City and adjacent areas (upstate New York, Newark, New Jersey, and Connecticut) were strongholds of the roll-top pattern in wooden- and woven-bottom seating. Modest production of the roll-top Windsor also can be noted in eastern Pennsylvania, eastern Massachusetts (fig. 18), and other locations. New York chairmakers probably introduced the roll-top chair during the late 1810s, although most evidence supporting the prominence of the pattern appears later. The distinctive, turned top piece was already current abroad in 1802 when illustrated and described as a “roller” in The London Chair-Makers’ and Carvers’ Book of Prices for Workmanship. The pattern probably was fashionable in New York in 1819 when John K. Cowperthwaite (fl. 1807–1833) used a woodcut of a roll-top, cane-seat fancy chair to illustrate an advertisement. That chair was not a stock cut but appears to have been designed for Cowperthwaite’s personal use: the front legs are terminated by typical New York, carved paw feet and the midback crosspiece is a pattern that appeared in the 1817 New York Book of Prices for Manufacturing Cabinet and Chair Work (see fig. 31).[41]

David Alling of Newark, New Jersey, whose chairmaking accounts provide a window on the New York trade in the absence of comprehensive records for that city, constructed roll-top seating between 1827 and 1839 (and perhaps earlier, since his records for the early 1820s are incomplete). Fellow chairmakers Benjamin W. Branson (d. 1835) and Richard D. Blauvelt (fl. 1824–1852) made roll-top chairs in New York during the 1830s. Records for craftsmen residing upstate in Otsego County document an active trade in roll-top (also called roll-back) seating from the mid-1820s until the early 1850s and probably reflect activity throughout the region.[42]

In neighboring Connecticut, where many more records survive, trade was brisk. Levi Stillman (1791–1871) of New Haven first recorded the roll-top pattern in 1822. Two years later he sold “6 doz roll top Windsors” for export priced at $90. Roll-top chairs were also in demand in the central part of the state, as corroborated in the records of Elizur Barnes (Middletown), David Pritchard (Waterbury), and Philemon Robbins (Hartford). James Gere (b. 1783) had many requests for roll-top Windsors at his coastal shop in Groton. Some customers ordered suites of side chairs and armchairs.[43]

A lesser-known roll-top chair of eastern Massachusetts origin is illustrated in figure 18. Its extra embellishment placed it at the top of the market in the Lunenburg shop of John D. Pratt (1792–1863). Fancy front legs and stretchers, which reflect considerable influence from New York vernacular design, replace the usual bamboo-type supports. The most prominent and unusual feature of the chair is, however, the seat—a design referred to during the period as a raised seat and a type more common on rocking chairs than on stationary chairs. The curves are achieved by adding a half scroll at the lower front edge and gluing up the back extension, or “rise,” from one or more stacked pieces of wood. Elbridge Gerry Reed of Sterling, Massachusetts, first mentioned a raised seat in 1834. Jacob Felton and Josiah Prescott Wilder of New Hampshire and Thomas Boynton of Vermontalso made chairs with this seat in the mid-1830s. On one occasion Philemon Robbins of Hartford identified the seat by its profile, calling it an “ogee seat.”[44]

During the 1820s when the slat-back styles (figs. 15, 16) rose to popularity, tablet-framed patterns (fig. 13) were less prominent than in the 1810s; however, renewed interest at the end of the decade brought both squared- and rounded-end examples into the market. Craftsmen continued to frame many tablets on round tenons. In an alternative construction, they attached the crest to the flattened faces of the back posts at shallow ledges, or rabbets, and secured them from the back with screws (fig. 19). This assembly method gave rise to the term screwed-back (or screwed-top) chair, although the crest piece itself varied in profile. Elbridge Gerry Reed of Sterling, Massachusetts, framed chairs of this design by 1829.[45]

The side chair illustrated in figure 19 has an unusual feature—a scroll seat, formed by attaching a half scroll to the seat front. Unlike the raised seat (fig. 18), there is no elevated back structure. Chairmakers, including Philemon Robbins of Hartford, Connecticut, used this construction for rocking chairs and top-of-the-line stationary seating. Thomas Walter Ward II stocked scroll-seat chairs at his store in Pomfret, Connecticut, in 1838, and Josiah Prescott Wilder still framed chairs of this description two decades later at New Ipswich, New Hampshire.[46]

A tablet with an extension at the center and large rounded ends, frequently shouldered as illustrated in figure 20, was popular in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and adjacent areas from the late 1830s. Preceding this pattern was a large, rectangular tablet with a generous overhang at the ends, which originated in Baltimore (see fig. 32). That city gave its name to the general style. Chairmakers used either round tenons or rabbets to frame the top piece. Frederick Fox (fl. ca. 1840–1877) offered “Baltimore Chairs” for sale in 1845 at the sign of the “Red Chair” in Reading, Pennsylvania. Three years earlier, appraisers itemized sets of Baltimore-style chairs in the estate of Charles Riley at Philadelphia; a few were painted in imitation maple. Loose top pieces in the shop were referred to as “Baltimore Bows.”[47]

The popularity of Baltimore-style chairs extended to New York and New England, where imitations were of a general nature only. In 1835 Benjamin Branson of New York supplied local chairmakers with Baltimore chairs: in July Tweed and Bonnell (fl. 1823–1843) bought “two Bondls of Boltimore Stuff” for framing. On August 29, Branson credited James Vanderbilt (fl. 1830–1835), a painter and chairmaker, for painting and ornamenting twenty-five dozen Baltimore chairs. The same day he sold the chairs to the firm of Benjamin and Elijah Farrington (fl. 1826–1835) for $7.50 a dozen, a price that allowed the partners to make a profit. At Sterling, Massachusetts, Elbridge Gerry Reed contracted with Benjamin Stuart (1793–1868), a fellow chairmaker, from November 1837 to February 1838 to frame a total of 360 Baltimore chairs for regional distribution. The presence of “36 Baltimore Chairs unfinished” in the shop of Daniel W. Badger (1779–1847) at Bolton, Connecticut, a decade later underscores the longevity of the style.[48]

A new feature of the Windsor chair during the 1840s was a bold vertical back splat, or banister, adapted from contemporary formal furniture and based generally on eighteenth-century design (fig. 20). By midcentury Pennsylvania chairmakers had introduced the pierced banister. Outside Pennsylvania the banister-back support is found most often in wood-seat chairs made in Maryland, northern New England, and the Midwest.

Fancy Chairs

The earliest evidence of fancy chair making in America dates to the mid-1780s. Samuel Claphamson (d. 1808), cabinetmaker and chairmaker “late from London,” settled in Philadelphia and advertised modish furniture, from commode sideboards to fancy chairs. During the 1790s several New York craftsmen became associated with fancy chair making. William Palmer (fl. 1787–1841), who began as a painter and gilder, advertised fancy seating furniture in 1796. He was followed by John Mitchell (fl. 1796) and William Challen (fl. 1796–1833), both chairmakers from London. Challen advertised “every article in the fancy chair line . . . after the newest and most approved London patterns,” which pinpoints the origin of the new painted form. The fancy chair differs from the Windsor in its basic construction. The seat is an open frame fastened to long, continuous back members and finished with a woven bottom.[49]

The earliest identifiable American fancy chairs date from the start of the nineteenth century and originated in Baltimore, a center that quickly achieved prominence as a producer of painted furniture (fig. 21). Here, the principal feature of the chair back is an urn-shape banister flanked by slim, flat sticks of complementary profile, possibly the “Urn spindles” of William Haydon’s and William H. Stewart’s (fl. ca. 1809–1818) black and gold chairs made in 1818 at Philadelphia. Both elements are included in George Hepplewhite’s The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide in engraved plates dated 1787. The slim crest with a modest overhang at the posts is of slightly later date. A prototype is illustrated in the 1802 London Book of Prices, where it is called a “tablet top.” That volume also includes posts with a backward bend, or “sweep.” The fancy chair profile served as a model for the later introduction of bent backs to Windsor seating.[50]

A feature of note at the center of the crest in the Baltimore chair is the painted ornament symbolic of music. Brothers John and Hugh Finlay (fl. 1803–1816), who in the early nineteenth century rose to prominence as chairmakers in Baltimore, described this and other ornaments suitable for crest pieces in an 1805 advertisement: “real Views, Fancy Landscapes, Flowers, Trophies of Music, War, Husbandry, Love, &c.” This description, in turn, leads to another that further expands on the nomenclature of the chair back. Henry May and Thomas S. Renshaw (fl. ca. 1816–1818), newly in business as chairmakers in Chillicothe, Ohio, in February 1816, identified part of their output as “Broad Tops with landscapes.” Renshaw had recently worked for several years in Baltimore. Three years later at Norfolk, Virginia, Humberston Skipwith purchased “12 Broad top Chairs” from the shop of Joshua Moore (fl. 1804–1819) for his home in Mecklenberg County. This second reference reinforces the supposition that broad-top commonly described the rectangular tablet that was a trademark of the Baltimore style in fancy and Windsor seating for four decades.[51]

One of the two seating materials of the fancy chair was cane, a woven, open material particularly suited to warm climates. An 1804 schedule of property in the Boston shop of William Seaver (fl. 1793–1837) lists “82 India Cane Bottoms.” Further insight on this item occurs a few years later in an advertisement by Asa Holden (1762–1854) of New York, who, while speaking of his fancy chairs with cane or rush seats, noted: “The cane seats are warranted to be American made, which are known to be much superior to any imported from India.”[52]

Were it not for the records of David Alling of Newark, New Jersey, two distinctive turned-spindle patterns would be anonymous today, and the chairs they embellish would be known simply by the generic term spindle-back (figs. 22, 23). In records dating from 1801 to 1804, Alling described the double-baluster turning of the first pattern as a “Cumberland Spindle” (fig. 22). Complementing the spindles in the chair back (and under the arms when present, see fig. 23) were “Cumberland front rounds,” or stretchers. If Alling’s records were more complete, they would likely show that the pattern remained current through the decade and beyond. Allen Holcomb of Otsego County in upstate New York used the term occasionally into the 1820s, principally to describe sticks in wagon chairs. The source of the word Cumberland is obscure.[53]

Some chairs framed with Cumberland spindles have a slim slat, or bender, for a crest piece. Others are constructed with cross rods at the top (see fig. 23). The tapered front legs of the chair in figure 22, rounded at the top and marked by an inset cuff near the bottom, are sometimes found onother fancy chairs associated with New York. The long posts of the back, although based on those used in eighteenth-century vernacular seating (see fig. 1), are reduced in diameter, tapered top and bottom, and bent and framed to flare outward and backward slightly.

The woven rush used to seat this chair was more common than cane and less expensive. Rush was often referred to in the trade as flag. It was purchased and stored in bundles. David Alling sometimes acquired as many as five hundred bundles at a time, much of it obtained in New York where it was brought in on sloops and often sold at the dock. In his records for 1828–1829, Elisha Harlow Holmes (b. 1799) of Essex, Connecticut, identified both “dry flags” and “green flags” and noted that he had paid to have flag cut at waterside and ferried to a pickup point. Rush had to be properly cured, or dried, before it was bundled and stored; otherwise it rotted and became unfit for use.[54]

Gaps in Alling’s records make it impossible to know the exact length of time he produced the organ-spindle chair, another spindle-back pattern (fig. 23). The period from 1815 to 1820 is highlighted in his records, but the chair probably was available commercially as early as 1810. Alling framed both top-of-the-line Windsors and fancy chairs with organ spindles in a range of colors. Organ spindles are named for their resemblance to the pipes of the musical instrument. The creased sticks of this pattern complement the framework that supports them. An almost identical side chair, which bears the label of New York chairmaker George W. Skellorn (b. ca. 1775), is accompanied by a printed billhead inscribed in 1819 that identifies it as a “Bamboo chair.”[55]

Imitation bamboowork was popular for several decades in New York City and surrounding areas. Alling produced chairs of this type with rush or cane seats between 1801 and 1822. On Manhattan Island, bamboo chairs usually sold for $2 to $2.50. William Palmer’s cane-seat chairs were priced at the higher figure, as were William Buttre’s (1782–1864) “bamboo fancy and gold Cheirs.” Evidence from across Connecticut—from New Haven and Groton to Middletown, Waterbury, and Litchfield—supports the popularity of the fancy bamboo chair in a region heavily influenced by the New York furniture market. Prices were comparable. As far north as central Vermont “gilt fancy bamboo chairs” were de rigueur in stylish public houses. Frederick Pettes ordered half a dozen chairs from Thomas Boynton in 1815 at a cost of $3 apiece for his inn at Windsor.[56]

Rush seats in quality fancy chairs were frequently painted, both for durability and decorative effect. Elizur Barnes of Middletown, Connecticut, sold “white Paint for Cheir Seets” to a customer in 1824. When working for Silas Cheney of Litchfield, Connecticut, in 1808, William Butler (fl. 1807–1809) put seats in six fancy chair frames and then painted them “2 Cots.” A parallel reference in the Alling accounts provides additional information: “To matting, moulding & ptg seat 2 coats.” Matting described the process of weaving a rush seat. In moulding a matted seat the chairmaker took strips of wood (the “moulding”) and nailed them around the outside edges to form a casing that could be painted and ornamented. The seats of the chairs in figure 23 have been finished in this manner.[57]

Closely associated with the bamboo style in period records are chairs whose framework is secured with ornamental cross sticks and turned balls (fig. 24). Sometimes the horizontal pieces are squared; here they are turned with small hollows, or spools, that add significantly to the ornamental effect and complement the hollows and bands of rings in the vertical members. Variant patterns employ a slat or roll at the crest and multiple cross sticks and balls at midback.

Both David Alling of Newark, New Jersey, and Silas Cheney of Litchfield, Connecticut, made ball-back bamboo fancy chairs by the mid-1810s and probably earlier. Both acquired much of their stuff for framing from suppliers. Alling’s sources were local; Cheney carted his prepared materials from as far away as Lee, Massachusetts, located due north in Berkshire County. Retail prices realized for ball-back chairs were about the same as those for organ-spindle chairs. On two occasions in 1819–1820, however, Alling described high-end market products: “ball back bamboe, Gilt balls, rush seats” and “ball back, green & Gilt, bronsed, rush [seats],’’ priced at $3.34 and $4.17 apiece, respectively. The higher-priced chair was also available in yellow; bronzing was the period term for stenciling. In later years the name ball-back was also applied to Windsor chairs with ball-turned vertical spindles, although a few Windsors were made during the 1810s in the fancy style of the chair in figure 24.[58]

An optional feature of ball-back bamboo chairs (fig. 24) and organ-spindle chairs (fig. 23), as noted by Alling, was the outward, forward flare of the lower front legs. When shipping chairs with similar legs to New Orleans in 1819, the chairmaker identified the supports as “bent front feet.” Legs without this feature were described simply as “Strait front feet,” when such differentiation was necessary. The 1802 London Book of Prices illustrates a closely related leg and describes it in a section titled “Sweeping, Toeing, and Rounding Front Legs.” There, however, the bend, or “sweep,” of the lower leg was produced on the lathe. Tiny, beadlike toes of the type illustrated in figure 24 remained popular for several decades.[59]

A diverse selection of early nineteenth-century documents provides insights on a fancy chair introduced just before 1810 that was framed with either a single-cross or a double-cross “splat” in the back (fig. 25). The top half of William Buttre’s two-scene tradecard, which depicts the painting room at his New York manufactory, shows workmen adding decoration and applying a finish coat of varnish to cross-back chairs in the two styles. Buttre’s auxiliary location on Crane Wharf is first cited in the city directory for 1813.[60]

The 1802 London Book of Prices illustrates three designs for chair backs with single “angular splats.” London influence in fancy chair design was also transferred to America in another way. Samuel J. Tuck (1767–1855), a chairmaker and importer of painters’ materials at Boston, expanded his business soon after the turn of the century to include imported furniture. His October 15, 1803 advertisement describes “London made Chairs, newest fashion viz. . . . black and [gold] cross back chairs.” Circulation of the London price book and the availability of London-made cross-back chairs eventually influenced fancy chair production in several coastal American cities, although interaction between the Atlantic seaports also remained strong. On December 12, 1810, Boston chair dealers Nolen and Gridley (fl. 1810–1813) announced that they had just received “from one of the first Manufactories at New-York—300 Fancy chairs, of different patterns, some elegant . . . viz . . . green and gold double Cross Backs . . . white and gold double cross d[itt]o.’’[61]

Prior to commissioning his pictorial tradecard, Buttre used a printed billhead with the address and text accompanied by a woodcut of a single-cross fancy chair. An inscribed copy is dated 1810, the year the same text and cut appeared in the advertising section of the New York City directory. David Alling probably already produced the cross-back pattern at Newark, although a hiatus in his accounts from 1807 to 1815 (and during the late 1810s) precludes knowing this fact for certain. The chair manufacturer framed both single- and double-cross chairs in 1815–1816. Ground colors of green and white are mentioned; the decoration was “Bronzed,” gilt, or striped. Alling’s records also mention “dimond front rounds,” braces similar in design to that at the front of the single-cross chair. Allen Holcomb in his migratory travels from Connecticut to Otsego County, New York, constructed cross-back chairs about 1809–1810 in the shop of Simon Smith (d. 1837), at Troy on the upper Hudson River. The chairs probably were little different from those manufactured at New York and Newark. During the 1810s, Baltimore, Boston, and Philadelphia chairmakers produced their own cross-back chairs; subtle differences distinguish one from the other. A few Windsors also were made in the cross-back style.[62]

A Boston fancy chair of modest popularity in its several variations is identified by a single, one-line reference in the probate inventory of Benjamin Bass, a cabinetmaker and chairmaker of the city who died in 1819 (fig. 26). The nine “3 Stick” chairs standing “In Price’s Store” had wooden bottoms, although the pattern is better known as a fancy chair than as a Windsor. Three-stick backs apparently had their genesis at the start of the 1810s, a time when Samuel Gragg (1772–1855) of Boston used similar two-stick and three-stick braces as stretchers in the front of some of his “elastic,” or bentwood, chairs. With its tablet-centered crest, the side chair illustrated in figure 26 appears to be an early cross-stick design. The visual rhythm of the crest, the three-stick lower back, and the two-stick front brace appears to owe a considerable debt to the New York ball-back chair (fig. 24) or a related pattern. Nolen and Gridley’s importation of New York chairs in 1810 opens the door to this possibility. There is also a remarkable similarity in the ringed, bent, and toed “feet” of the Boston and New York chairs, a pattern that, by the end of the decade, had broad distribution.[63]

Sweep (bent) back posts, with their surfaces shaved to provide a convenient surface for ornamentation, all but replaced round (cylindrical) posts (figs. 21–23) by the late 1810s. Open-stick and tablet-centered crests also gave way to solid slat styles (fig. 27) in the pursuit of painted decoration. The chair in Thomas Cotton Hayward’s (1774–1845) advertisement appears to have swelled and reeded legs, a pattern that may have been another New York importation. The front stretcher, consisting of an oval tablet flanked by tiny, flat-faced beads, is a Boston feature, however, and appears in chairs of several patterns. A Windsor chair with a back similar to that in figure 26 has a front stretcher of this design. Tablet tops replaced slats as crest pieces in three-stick chairs by the 1820s, and, the pattern was carried into the late 1830s. Three designs are common: a rectangle with hollow corners, a flared rectangle with an upper-back roll, and rounded-end tablets.[64]

A fret can be defined as a panel or a panel-like form that is pierced through or shaped around the outside, or both, to create a decorative pattern. Cabinetmakers and chairmakers alike used frets to good advantage in the backs of formal and vernacular chairs. The use of frets in seating furniture was already current in London when a lattice-type example with diamond-shape piercings appeared in the 1802 London Book of Prices.[65]

Like many fancy chair patterns, the fret-back style may have originated in New York. Asa Holden of that city used a woodcut of a fret-back chair in an advertisement that began in 1812. John K. Cowperthwaite’s pictorial billhead inscribed in 1816 but printed about 1810 to 1812 illustrates a similar fancy chair (fig. 28, left). The diamond-like fret is the same pattern as that in the London price book. Indeed, “dimond fret back” fancy chairs are itemized in the accounts of David Alling of Newark, New Jersey, in 1819 and Henry Wilder Miller (1800–1891) of Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1827. By then, diamond-fret fancy chairs had been illustrated in advertisementsby Thomas Sill (1776–1826) of Middletown, Connecticut (1814), and by Caleb(?) Davis and John Bussey (fl. 1819) of Albany, New York.[66]

A highly ornamental pattern in fretwork pairs leaf forms and small balls, or beads. The armchair shown in figure 29 illustrates a large set of fancy furniture comprised of twelve side chairs, two armchairs, and a settee that was purchased in New York through an agent in 1816 by a Portsmouth, New Hampshire, resident. The rounded-front seat, which is typical of New York production (see figs. 23–25, 28), is referred to as a “Bell seat” in the 1817 New York Book of Prices. Allen Holcomb framed “8 bell Seat Chairs” and “Cased” the seats when working for Simon Smith at Troy, New York, in 1810. The terms casing and moulding appear to have been interchangeable. Arms of the general type on this chair are illustrated in the 1802 London Book of Prices, which describes them as “scroll elbows” on “turn’d stumps.” The pattern apparently was common for seating furniture framed with leaf-and-bead frets, because armchairs from at least five different sets have elbows and supports of this design.[67]

The introduction of fretted panels to New York chairs had a substantial impact on fancy chair making in Connecticut because of the strong commercial interaction between the two areas. As previously mentioned, Thomas Sill of Middletown illustrated a diamond-back chair in an 1814 advertisement. Thomas West (1786–1828) of New London made “Fancy Chairs of the latest and most approved New York Fashions,” and at Redding, James S. Chapman (fl. 1809–1810) sold his “warranted” chairs at “New-York prices.” Levi Stillman, a furniture maker of neighboring New Haven, recorded the sale of both fancy and Windsor fret-back chairs during the 1820s. The cost of “getting out frets” by shop journeymen was recorded as 8¢ and 121/2¢ by James Gere of Groton and Silas Cheney of Litchfield. The patterns probably were different; the cost reflects the intricacy of the profile, the number of piercings, or both.[68]

The fret of a fancy chair made in Connecticut has an intricate top profile (fig. 30). Seymour Watrous (fl. 1824–1825) of Hartford illustrated a comparable fret-back chair in 1824 when advertising his start in business. The front stretcher of the chair in the woodcut appears to duplicate the uncommon profile of the example illustrated here, with its central reel flanked by urn-shaped turnings. A square seat and turned crest are also features of both chairs. The roll-top is, in fact, more common than the slat-back with the scroll-type fret. Chair surfaces are about equally divided between painted finishes and natural maple. In 1819 David Alling of Newark, New Jersey, shipped “one doz fret back Curled maple [chairs] in good order” to New Orleans for sale on commission. If some of Alling’s chairs had arms, they may have looked like these, which duplicate the posts and scrolls of a New York chair (see fig. 24).[69]

A chair fret of a different type than those in the previous examples was introduced to the New York furniture market in the late 1810s (fig. 31). The pattern is delineated in the 1817 New York Book of Prices, with an oval tablet at the center instead of a rectangular one. The price book describes the crosspiece as a chair banister “with double Prince of Wales feathers, tied with a gothic moulding.” Chairmakers used the distinctive back piece in joined, fancy, and Windsor seating furniture. The pattern was exceedingly popular, particularly in curled maple and with the central element carved in an open leaf pattern. The general style appears to have remained fashionable throughout the 1820s. The fret may have been the one identified in 1829 at a furniture auction in Salem, Massachusetts, as a “N. York back.” David Alling shipped chairs to New Orleans in 1820 described as “1 doz ovel fret backs, gilt and bronsed rose wood, rush seats.” The term oval may refer to the central tablet of the back piece, as illustrated in the price book.[70]

Prince of Wales feathers as decorative elements had appeared earlier in New York chairs. One of the designs in Thomas Sheraton’s The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterers’ Drawing Book (1793) was popular in joined seating at the turn of the century. The principal ornament of the center back is a tall urn, or vase, surmounted by plumes tied at the center with a knot, or “moulding.” Redesigning the feather motif as a horizontal fret was an easy task in an innovative chair market such as existed at New York. The profile is repeated to good effect between the front legs, although braces of this design are rare. The moldings, or casings, enclosing the rush work of the seat differ from those in bell-seat chairs (see fig. 29). The back and side pieces are flat, shaped strips nailed in place. The front piece, which is half of a turned cylinder, is attached in the same manner to the corner leg blocks. Here, it coordinates in profile with the fret and front brace and is considerably more ornate than usual (see fig. 30).[71]

Figure 32 shows a later version of the Baltimore tablet-crested chair illustrated in figure 21, a seating form identified by May and Renshaw in 1816 as a broad-top chair. In some regions broad-top chairs fitted with a small rolled lip at the upper back edges of the crest were called scroll-top chairs. Baltimore residents knew this particular seating piece as a “Circle Chair” or “Single side piece” chair. The terminology, which was used by Bryson Gill (fl. 1822–1831) in an 1824 advertisement, focuses on the unusual seat frame with its rear cylinders. The following year John R. Robinson (fl. 1812–1845), the maker of this branded chair (fig. 32), emphasized his “SPLENDID ASSORTMENT OF CHAIRS . . . made portable” for shipping. Baltimore in the 1820s was a flourishing center of the furniture export trade.[72]

Neoclassical design in Baltimore furniture was an adaptation of classical forms and decoration as interpreted in European centers, principally London and Paris. Baltimore craftsmen became acquainted with the style and its motifs through design books and imported furniture. Hugh Finlay (1781–1830), the leading painted furniture manufacturer in Baltimore, even traveled to Europe in 1810 to acquaint himself better with developments. The “circles,” or cylinders, in the seat of this chair (fig. 32), accented by applied, pressed-metal rosettes, although an uncommon feature, suggest pivoting or movable joints, a theme that recurs in neoclassical design. Baltimore circle chairs usually have Roman (tapered cylindrical) front legs and baluster supports at the back, above and below the seat. All the terminals are accented at seat level with multiringed ball turnings, an element present in other painted forms made in the city. The ambitious floral decoration of the crest bears a strong resemblance in composition to ornament on furniture documented to the shop of John Hodgkinson (fl. 1822–1857) and, in finer form, to work attributed to Hugh Finlay.[73]

The crown-top was one of the two most popular fancy chair patterns in New England during the 1830s (fig. 33). Equally in demand was the roll-top chair (see fig. 30). The crown-style top piece, with its distinctive scroll ends and raised center, probably was introduced to the furniture market at the end of the 1820s, and Connecticut appears to have been the chief center of production. Like other nineteenth-century furniture designs, the crown profile originated in Europe and was transmitted to America through printed materials and exported furniture. One of the earliest representations of this top piece appears in the October 1815 issue of Rudolph Ackermann’s The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics. By the mid-1820s, design books by P. and M. A. Nicholson and George Smith illustrated similar patterns.[74]

An early reference to the American crown-top chair is in the accounts of David Pritchard of Waterbury, Connecticut, under the date 1832. Two years later Pritchard’s brother-in-law, Lambert Hitchcock (1795–1852), signed and dated a receipt for “6 Crown top Rich g[il]t chairs” sold to a private customer at Hitchcocksville (now Riverton). Entrepreneur Hitchcock was also represented in Hartford. Isaac Wright (1798–1838) and Philemon Robbins stocked Hitchcock’s crown-top chairs in their furniture stores. Both rush- and cane-bottom chairs were available to consumers, as itemized in the insolvency inventory of Frederick Parrott and Fenelon Hubbell (fl. 1835) of Bridgeport. The records of David Alling of Newark, New Jersey, indicate that crown-top chairs were also made and marketed in the greater New York area. Construction of the crown crest in rabbets on the faces of the back posts, the joints secured by screws, suggests other terms that may have identified this top piece and related round-end patterns. Elbridge Gerry Reed framed hundreds of “Screwd back” chairs in Sterling, Massachusetts, during the 1830s at a time when chairmakers in the southern market were constructing stump-back chairs, a term that refers to the blunt tips of the back posts.[75]

The “1 doz. crown top oval fret scroll front” chairs that David Alling delivered in 1833 to Joseph W. Meeks and Company in New York appear to have resembled the chair in figure 33. There are no other candidates in the 1830s for the “oval fret.” Parrott and Hubbell’s insolvency records at neighboring Bridgeport describe another term for this distinctive back piece: “frog fret.” The curved elements that tenon the fret to the posts simulate the legs of the amphibian. Again, the pattern may have been inspired by a European source. The plate from Ackermann’s Repository delineating the possible prototype for the crown top illustrates another chair with a fret remarkably similar to this one.[76]

Records relating to Philemon Robbins, Peter A. Willard, and Jacob Felton, chairmakers of Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire, respectively, describe “turkey legs” or chairs framed with these supports. The only obvious candidate is illustrated in figure 33. The joint above the bird’s claw foot remains, and the multi-ring turnings simulate its fluffed feathers. Aside from serving as a brace between the front legs, the scroll-type stretcher, which is a rarity, serves to unite the upper and lower structures of the chair.[77]

Figure 34 shows one of several early nineteenth-century interpretations of classical seating furniture that falls under the general umbrella of Grecian furniture. Before that name became generally current in American furniture-making circles, the term scroll-back was in use. Characteristically, the structure of the chair above the seat exhibits an ogee curve in profile, the post tops scrolling backward and the lower ends sweeping forward to the roll at the seat front. The legs are usually of a hollow-curve, or klismos, form. Elements of the Grecian style, as described, are delineated in the 1802 London Book of Prices. In 1807 Thomas Hope published a line-engraved side view of a scroll-back chair in Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (London), and drawings of relatively simple scroll-back chairs are included in the March 1809 and December 1811 issues of Ackermann’s Repository, both publications known to have circulated in America.[78]