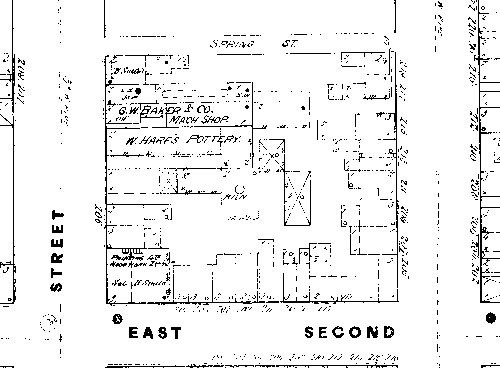

Hare Pottery Shop, as illustrated on Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1884.

Canning jars, Hare Pottery, Wilmington, Delaware, ca. 1860. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 3/4", 7 1/2", and 8". (Right, left: Courtesy, private collection; center: Courtesy, Delaware State Museum; photo, Charles Fithian.) All are impressed: “WM HARE / WILMINGTON DEL.” Manufactured to preserve fruits and other foodstuVs, this vessel type is the predecessor of the glass Mason jar.

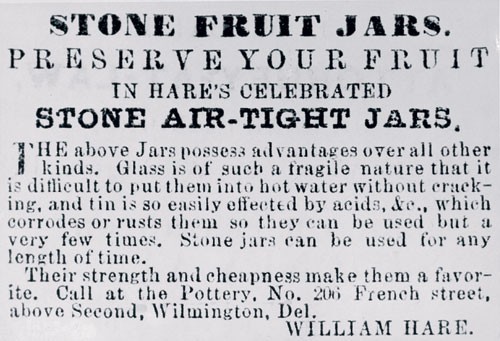

Fruit jar advertisement, Delaware Gazette, September 3, 1869.

Crock, Hare Pottery, Wilmington, Delaware, ca. 1860. Salt-glazed stoneware with cobalt decoration. H. 4 1/2". (Courtesy, Delaware State Museum; photo, Charles Fithian.) Impressed under rim: “WM HARE / WI ... DEL.”

The traditional pottery of Delaware is poorly known. One exception is the work of William Hare (act. 1837–1885), an earthenware and stoneware potter of Wilmington, who had the only shop in Delaware to routinely stamp ware. His life and pottery are currently being studied by the Delaware State Museum.

Hare was raised in Columbia, Pennsylvania, but it is not known where he learned his trade and served his apprenticeship. He had ties with eastern Pennsylvania—several potters linked to that area were employed by him, and he and his wife were married in Philadelphia in 1842, although both were living in Wilmington at that time.

William Hare came to Wilmington in 1837. He purchased an existing pottery shop on French Street and remained there through 1885 (fig. 1). Records show that he variously employed between four and seven workers and had one or two horse-driven pug mills.[1] His production began with earthenware and about 1860 switched to an emphasis on stoneware. In 1860 his shop produced forty-five kilns of earthenware and stoneware ($5,400 value). Although he is best known for his storage jars—predecessors of the glass Mason jar (figs. 2, 3)—Hare also produced churns, jugs, bottles, pitchers, milk pans, and baking crocks (fig. 4).

For an operation with four to seven workers, Hare’s pottery shop had a surprisingly high rate of staff turnover. Between 1844 and 1880 the following are documented as working there:

1844–1848: William Rogers (apprentice)

1845: Levi Adams, possibly Spencer Williams

1850: Henry Bell, William Desney, Benjamin McShane, John Stuben

1853: Samuel Bradford

1857: Engelbert Neumayer, Jacob Schiller, William Smith, George Zigler

1859: Charles Decker (listed as Dacker), William Smith, Randolph Weir, George Zigler

1860: Engelbert Neumayer, Jacob Schuler, George Zigler

1862: Samuel Bradford, Charles Decker (listed as Dacker), Randall Weir, Levi Williams

1870: Four over age 16, one child

1880: Three over age 16, one child[2]

Charles Decker, Engelbert Neumayer, Jacob Schuler, and John Stuben were all born in Germany and probably trained there as well. Decker had previously owned a shop in Philadelphia and later established shops in southwestern Virginia and eastern Tennessee.[3] Samuel Bradford had three years of potting experience in Chester County, Pennsylvania.[4] Levi Williams and Spencer Williams, possibly related, were African Americans. Neumayer worked for Hare in 1857 and early 1860, and Zigler worked for Hare in 1857, 1859, and early 1860; by late 1860, however, Neumayer and Zigler were co-owners of a competing shop.

If the available records are accurate, Hare had complete employee turnover every four or five years. Metric variability seen among 240 surviving marked pieces of Hare pottery is consistent with an ever-changing workforce. His shop, which was the largest in Delaware, employed four workers in 1880, whereas in the same year Trenton had 2,800 pottery workers.[5]

The Hare shop closed with his death in 1885, coinciding with the closing of many traditional shops along the eastern seaboard. Hare had tailored his product to the local farmers and fruit growers, and changed from earthenware to stoneware as the market shifted. However, inexpensive glass, industrial ceramics from New Jersey and Ohio, breakthroughs in metal can technology, and the development of home refrigerators combined to ultimately destroy the stoneware market.

Charles Fithian, Curator of Archaeology, Delaware State Museum; chuck. fithian@state.de.us

Claudia Leister, Collections Manager, Delaware State Museum; claudia. leister@state.de.us

James Stewart, Administrator, Delaware State Museum; jim.stewart@ state.de.us

Chris Espenshade, Archaeologist, Skelly and Loy, Inc.; cespenshade@ monroeville.skellyloy.com

U.S. Census, New Castle County, Delaware: Population Schedules of 1850, 1860, 1870, and 1880; Schedules of Manufactures of 1850, 1860, 1870, and 1880.

W. H. Boyd and A. Boyd, Boyds’ Delaware State Directory, 1859–1860 (New York: William H. and Andrew Boyd, 1860).

C. T. Espenshade, “Potters on the Holston: Historic Pottery Production in Washington County, Virginia,” report on file, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Richmond, Va., 2002.

Arthur Edwin James, The Potters and Potteries of Chester County, Pennsylvania (Exton, Pa.: SchiVer Publishing, 1978).

From Teacups to Toilets: A Century of Industrial Pottery in Trenton, circa 1850 to 1940 (Trenton, N.J.: Potteries of Trenton Society, 2001).