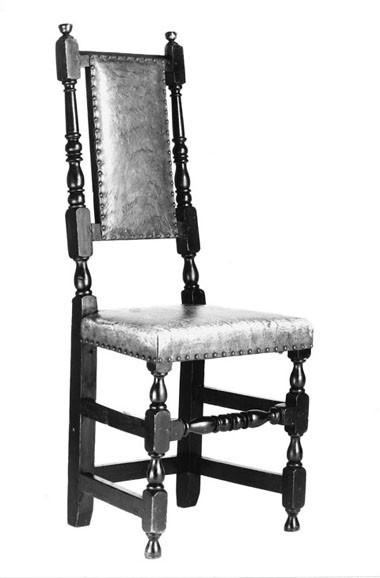

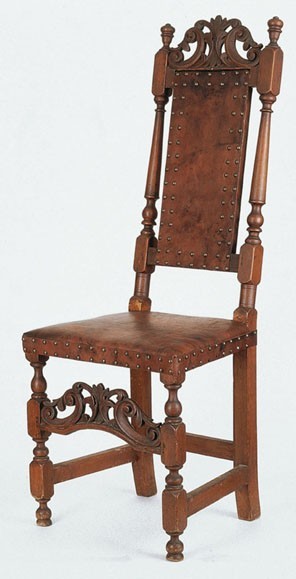

Side chair, Boston, 1700–1710. Maple and oak. H. 43 5/8", W. 17 5/8", D. 14 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

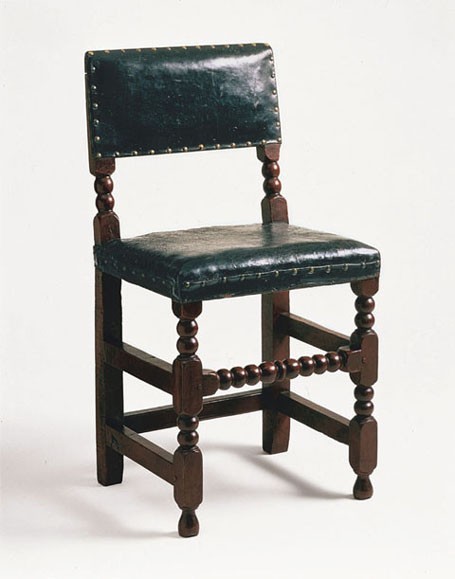

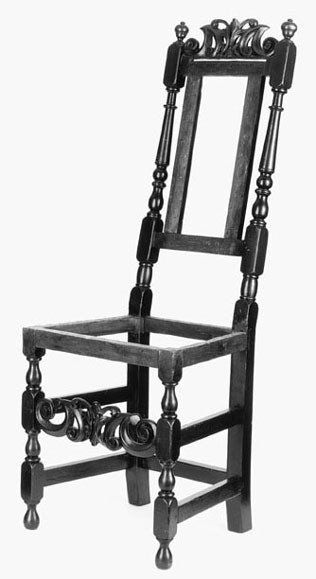

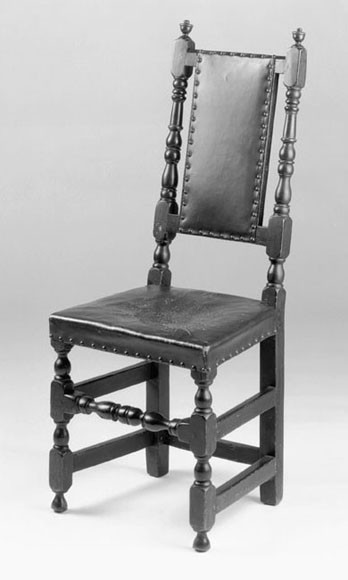

Side chair, Boston, 1650–1700. Maple and oak. H. 36", W. 18", D. 15 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

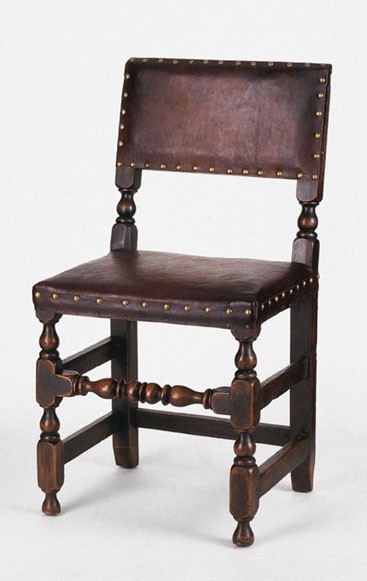

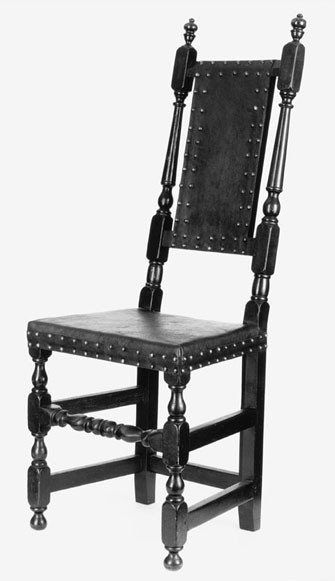

Side chair, Boston, 1685–1700. Maple and oak. H. 35 1/2", W. 18 1/2", D. 18 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

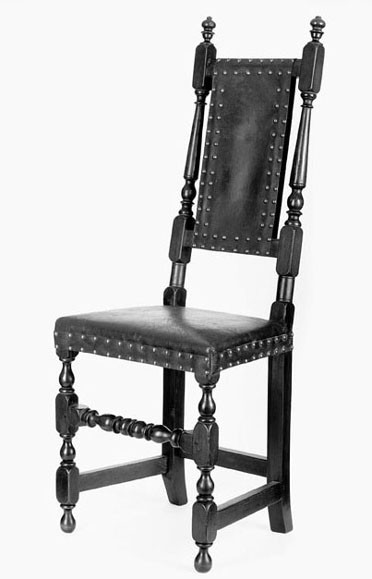

Side chair, Boston, 1700–1710. Maple and oak. H. 44 1/2", W. 18 3/8", D. 16". (Courtesy, Saint Louis Art Museum, gift of Mr. and Mrs. E. J. Nusrala.)

Side chair, Boston, 1710–1720. Maple and oak. H. 47 1/2", W. 18", D. 14 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Composite detail showing (from top to bottom) the front stretchers of the (a) late seventeenth-century, Boston low-back chair illustrated in fig. 3; (b) first-generation Boston leather chair illustrated in fig. 1; (c) second-generation Boston leather chair illustrated in fig. 5. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The armchair illustrated in fig. 25 has an identical rear stretcher of the same dimensions as those illustrated here.

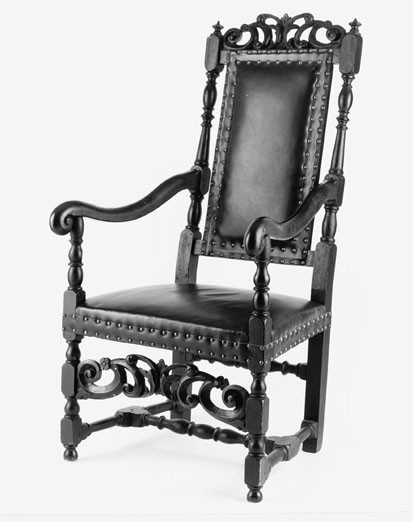

Armchair, Boston, 1700–1710. Maple and oak; original leather upholstery. H. 47 1/4", W. 23 1/2", D. 22 3/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Arthur Tracy Cabot Fund.)

Side chair, probably London, 1685–1700. Woods and dimensions unrecorded. (Photo, Symonds Collection, Decorative Arts Photographic Collection, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail of the hollow back of the side chair illustrated in fig. 29. (Courtesy, Milwaukee Art Museum, Layton Art Collection.)

Side chair, Boston, 1700–1710. Maple and oak. H. 47 5/8", W. 17 3/4", D. 14 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The carving on this chair is closely related to that on the New York side chair and New York armchair illustrated in figs. 23 and 24 and the Boston armchair illustrated in fig. 25.

Side chair, Boston, 1700–1710. Maple and oak. H. 46", W. 17 3/4", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The rear legs have been improperly restored to incorporate the backward rake.

Side chair, Boston, 1710–1715. Maple and oak. H. 47 3/8", W. 18", D. 14 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Boston, 1710–1715. Maple and oak. H. 48", W. 18", D. 14 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair retains the first-generation feature of a slit crest rail.

Detail of the carved crest rail of the chair illustrated in fig. 12. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carved crest rail of the chair illustrated in fig. 13. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the construction of the side chair illustrated in fig. 11, showing the planed surfaces of the front leg squares and overhang of the front stretcher. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

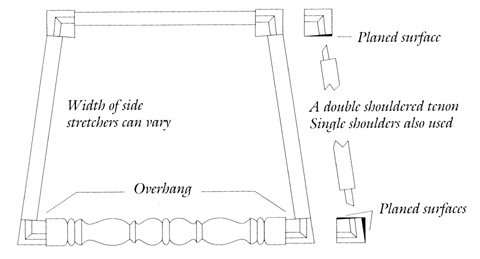

Diagram showing how the seat rails and stretchers join the front and rear legs on first- and second-generation Boston chairs.

Detail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 11, showing the characteristic chamfering on the rear legs of first- and second-generation Boston chairs. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, New York, 1700–1710. Maple and oak. H. 44 3/8", W. 17 3/4" , D. 14 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair was found in Newburgh, New York.

Side chair, New York, 1700–1710. Maple and oak. H. 44 3/8", W. 17 3/4" , D. 14 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair was found in Newburgh, New York.

Detail of the front stretcher of the side chair illustrated in fig. 19. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The characteristic elements are the extra balls on the outer ends. See also figs. 20, 24, and 28.

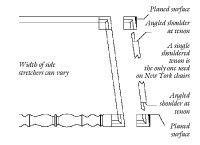

Diagram showing how the seat rails and stretchers join the front and rear legs on New York chairs.

Side chair fragment, New York City, 1700–1710. Maple and oak. H. 38", W. 17 3/4", D. 14 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair was found in Greenwich, Connecticut.

Armchair, New York City, 1700–1710. Maple with oak. H. 52", W. 24 3/4", D. 17 1/2". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, Boston, 1700–1710. Maple with oak. H. 53 3/4", W. 23 7/8", D. 16 3/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of Mrs. Charles L. Bybee; photo, Edward A. Bourdon, Houston, Texas.)

Gateleg table, New York City, 1690–1720. Mahogany with maple, yellow poplar, and oak. H. 28 7/8"; top: 40 3/4" x 44 1/2" (open). (Courtesy, Museum of the City of New York www.mcny.org, gift of the Reynal family; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, New York, 1700–1710. Maple with oak and hickory. H. 47 1/2", W. 25 1/2", D. 27". (Courtesy, Historic Hudson Valley, Tarrytown, New York.) The feet are replaced and the finials are incorrectly restored.

Armchair, New York, 1680–1700. Maple stained red. H. 44 1/4", W. 22 1/2", D. 22 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Christopher Zaleski.)

Side chair, Boston, 1700–1725. Maple, oak, leather. H. 45 5/8", W. 18 1/8", D. 15 1/4". (Courtesy, Milwaukee Art Museum, Layton Art Collection, L192.116; photo, Richard Eells.)

Side chair, Boston, 1700–1710. Maple and oak. H. 46 3/4", W. 18", D. 14 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chairs, possibly New Hampshire, 1700–1710. Maple and oak. H. 47 1/2", W. 17 3/4", D. 15". (Private collection.)

During the last few years of his life, Winterthur Museum curator Benno M. Forman developed an intriguing theory that three early eighteenth-century leather chairs in that institution’s collection (see fig. 1) originated in New York rather than in New England as had previously been thought. Two are very similar to another leather chair (fig. 4) that Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, curator Richard H. Randall, Jr., had earlier dubbed a “Piscataqua,” or Portsmouth area, version of the Boston leather chair. Forman’s catalogue, American Seating Furniture: 1630–1730, identified nine characteristics that distinguished New York chairs from what he called “standardized” Boston chairs. In an article titled “Hidden in Plain Sight: Disappearance and Material Life in Colonial New York,” historian Neil Kamil took Forman’s argument one step further. Kamil maintained that many of the chairs he and Forman attributed to New York were the products of Huguenot artisans who immigrated to that city after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685.[1]

This article presents two arguments that dispute Forman’s and Kamil’s attributions. The first is that the leather chairs in Winterthur’s collection are Boston chairs made during the first decade of the eighteenth century. They were the first seating forms to have evolved from the low-back “Cromwellian” chairs (or stools) made there from about 1640 to 1700 (figs. 2, 3). These “first-generation” leather chairs differ from Forman’s “standardized” Boston chairs, not because they were made in a different region but because they were made at an earlier date. The second argument is that New York leather chairs have consistent turning patterns and construction details that differ from contemporary Boston examples.

The Forman Attributions

Forman outlined the following nine characteristics as distinguishing New York chairs:

1. “New York chairs have complex, turned stiles with a short column, and either balls or short balusters atop long balusters. Flat bottom-caps (half round turnings) above the balusters are common.”

2. “On chairs that have barrel-like turnings on the stile between the seat rail and the lower back rail, the barrels have fat rings at their tops and bottoms.”

3. “The rear feet go straight down to the floor on the back side and are chamfered on the forward side.”

4. “Some chairs have double side stretchers, often of oak, and these are thicker than those on the Boston examples.”

5. “When the side and rear stretchers are rectangular in section rather than turned, the rear stretcher enters the rear legs at the same point that the side stretchers do.”

6. “When the front stretcher of a New York chair is turned, its ends terminate in blocks, which are joined to blocks on the front legs by mortise and tenon joints.”

7. “In order to get a sufficiently bold turning on such stretchers, a piece of wood thicker than the legs is used. Upon final assembly the front stretcher is fitted flush with the front of the legs and thus overhangs in the back, often more than 1/4".”

8. “On this chair [a carved-top leather chair that Forman attributed to New York] it [the top line of the upholstery on the back] is straight, with the characteristic slit through which the upholstery is pulled and tacked; on the usual Boston chairs, it is a rounded arch . . . that echoes the arch on the bottom edge of the front stretcher.”

9. A “hollow crest rail is common to New York chairs.”[2]

Although Forman was correct in asserting that leather chairs were made in New York and Kamil has documented the extensive involvement of Huguenot tradesmen in that city’s chairmaking industry, seven of the nine features cited by both authors as characteristics of New York chairs are actually features of first-generation Boston chairs. The two other characteristics are typical of both first- and second-generation Boston seating.

With its double side stretchers and complex post turnings, the side chair illustrated in figure 4 is an excellent example of a first-generation Boston chair with all of Forman’s “New York” characteristics. It features a leather seat and back panel, which were the most important visual components of baroque leather chairs regardless of their place of manufacture. The upholsterer used iron tacks to fasten the leather to the back of the crest and brass nails to secure it to the front faces of the stiles and rails. He also used brass nails to fasten the leather strips that cover the rough edges of the seat upholstery. The back of the chair is unupholstered, leaving the linen foundation for the marsh grass stuffing visible.[3]

Second-generation Boston leather chairs, most of which date after 1710, are the only ones Forman attributed to that city (see fig. 5). They typically have long columnar turnings flanking the back panel, scored cylindrical turnings above the seat, rear feet that rake backward, single side stretchers, and a rear stretcher positioned above the side stretchers. In addition, their back panels are often double nailed and unstuffed.[4]

The “Boston” Stretcher and the Evolution of Baroque Leather Chairs

The strongest evidence for attributing the first-generation leather chairs to Boston rather than to New York is their stretcher turnings. All have blocks at both ends and double opposed balusters (the inner one smaller than the outer one) flanking a central ring (see figs. 1, 4, 6b). Identical stretchers occur on seventeenth-century Boston low-back chairs (see figs. 3, 6a) and second-generation Boston leather chairs (see figs. 5, 6c), whose New England origins have never been disputed. The front stretchers on first- and second-generation side chairs are consistently 14 1/2" wide, the same dimension as many of the ball-turned stretchers on earlier Boston low-back chairs (see fig. 2). Elongated versions of this pattern (fig. 6a–c) occur on the front stretchers of Boston armchairs (fig. 7), which typically have wider seats, and on the medial and rear stretchers of Boston easy chairs made during the first two decades of the eighteenth century.[5]

Three other characteristics cited by Forman—straight rear legs with chamfered faces, double side stretchers, and rear stretchers set level with the bottom side stretchers—are also features of Boston low-back chairs (figs. 2, 3). The side chair illustrated in figure 3 is the only example with a “Boston” stretcher and with baluster turnings above the seat; nevertheless, it represents a transition between low-back chairs with square seats and ball turnings (see fig. 2) and first-generation chairs with high backs and trapezoidal seats (see figs. 1, 4).[6]

Forman also believed that New York leather chairs had rear posts with more complex turnings than their Boston counterparts. During the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, however, large numbers of English cane, turkeywork, and leather chairs (fig. 8) with similarly complex turnings were exported to the colonies, where they undoubtedly influenced regional turning patterns such as those on first-generation leather chairs (see figs. 1, 4). As the first-generation chairs passed out of fashion about 1710, the short baluster or barrel and ring elements above the rear seat rails became simple scored cylinders, and the columns on the back posts became elongated as the number of turned elements was reduced. At the same time, Boston chairmakers eliminated the upper side stretchers and raised the rear stretcher. Figures 2–5 illustrate the structural and stylistic changes that occurred as low-back chairs evolved into first-generation chairs and as they, in turn, evolved into second-generation chairs. From the high-back second-generation chairs (fig. 5), it was only a short leap to the Boston “crook’d back” chairs that were in vogue after 1720.[7]

Another feature that characterizes many first-generation, Boston “plain top’d” leather chairs is a slight hollowing of the back rails (fig. 9). Almost imperceptible on an upholstered and stuffed back, the concavity is readily apparent when the upholstery is removed and the chair is viewed from above. Late seventeenth-century English chairs occasionally had such backs, and many were imported into the colonies. No second-generation Boston chairs have this detail, however, nor do any first-generation “carv’d top” chairs, presumably because the hollowing would have made carving more difficult.

Several of the modifications exhibited by second-generation Boston chairs stemmed from efforts to simplify and expedite their construction. The elimination of details, such as turned elements, upper side stretchers, and hollow backs, reduced the costs of making the chairs, giving Boston chairmakers a competitive edge in the marketplace. Indeed, the prevalence of the “Boston” stretcher, with its consistent 14 1/2" length, suggests that artisans mass-produced individual components to achieve a higher level of efficiency. During the seventeenth century, Boston turners produced stretchers, table legs, pillars, and spindles for joiners, so it is logical to assume that this practice also occurred later.[8]

Not all of the attributes of second-generation Boston chairs resulted from efforts to simplify construction. The addition of a backward rake to the rear legs was a response to the increased height of the chair backs. The backs of most first-generation chairs are about 27 3/4" high (seat to finial), whereas those of some second-generation examples are as high as 31 1/2". Although the backs became taller, their pitch remained constant, making the later examples prone to tip over. The raked rear legs were more labor intensive, but they were necessary for stability (fig. 5).

On first- and second-generation chairs, customers could choose design features that affected both appearance and price, for example “carv’d top” or “plain top’d.” The carved-top, first-generation chair illustrated in figure 10 has a carved front stretcher and a conforming crest rail with a slit for the leather upholstery—a characteristic that Forman attributed to New York. This chair, however, also has turned rear posts that are virtually identical to a “plain top’d” side chair with a “Boston” front stretcher, dual side stretchers, straight rear legs with a chamfered heel, and other attributes of first-generation Boston workmanship (fig. 11). Considering the widespread importation of English leather and turkeywork chairs into the colonies, some of which undoubtedly had carved crests with slits (see fig. 8), it is surprising that Forman chose to “regionalize” this detail. New Yorkers apparently preferred the less expensive “plain top’d” chairs. In a 1709 letter to his New York agent Benjamin Faneuil (b. La Rochelle, France, 1658, d. New York 1719), Boston merchant Thomas Fitch (1668/9–1736) wrote, “I wonder the chairs did not sell; I have sold a pretty of that sort to Yorkers since, and tho some are carv’d yet I make six plain to one carv’d; and can’t make the plain so fast as they are bespoke, so you may assure . . . customers that they are not out of fashion here.”[9]

Figures 5 and 12 show two second-generation Boston side chairs with virtually identical back posts. The only vestige of first-generation workmanship on either chair is the distinctive “Boston” stretcher on the “plain top’d” example (fig. 5); both chairs have single side stretchers, raised rear stretchers, scored cylinders above the seats, and elongated columnar turnings on the back posts. A side chair with related post turnings (fig. 13) has an arched crest similar to that of the chair illustrated in figure 12. Although the carving designs are similar (figs. 14, 15), they are clearly by different hands. The carver of the crest rail illustrated in figure 15 was considerably more adept with his parting tool (a V-shaped tool used for making deep shading cuts). During the second decade of the eighteenth century, chairs with banister backs, flag seats, and “Prince of Wales” crests were less expensive alternatives to these second-generation, “carv’d top” leather chairs. Some of these examples also have “Boston” front stretchers.[10]

In addition to the ubiquitous “Boston” stretcher, construction details shared by first- and second-generation chairs suggest a common origin. Forman argued that the end blocks of the front stretchers overhung the backs of the front legs because New York chairmakers used thicker stock for the front stretchers in order to achieve bolder turnings. On all of the chairs examined for this article, however, the stock for the legs and front stretchers is the same thickness. The overhang resulted from Boston chairmakers planing the back sides of the front leg blocks (fig. 16), which allowed them to join the side stretchers to the legs at right angles (fig. 17). Another distinctive Boston construction detail is the chamfering of the back legs (fig. 18). Aside from this slight chamfer, the back legs are square, and, unlike the front legs, they are not planed away on the sides to continue the visual lines of the side stretchers along the surfaces of the legs, as they would be on New York chairs.[11]

All of the Boston side chairs Forman attributed to New York have dual side stretchers, and all of the armchairs have single side stretchers; however, the number of side stretchers is not an indicator of a chair’s place of origin. Seventeenth-century, Boston low-back side chairs invariably had double side stretchers (fig. 2), and contemporary armchairs, following English fashion, invariably had one.[12] This rule also applies to first-generation Boston armchairs with rectangular or turned stretchers such as the ones illustrated in figures 7 and 25. Although Forman recognized that all leather side chairs had rectangular side stretchers, he asserted that those on New York chairs were thicker than those on Boston chairs; however, stretcher thicknesses varied in both cities. Some of the first-generation chairs that Forman attributed to New York have thin stretchers with “barefaced tenons” (a tenon with one shoulder). These tenons, which were easier to cut and required less stock than conventional two-shouldered tenons, are often found on Boston Cromwellian chairs. When Boston chairmakers eliminated the upper stretchers on second-generation chairs, the remaining side stretchers needed the additional bearing surface of a second shoulder—requiring thicker stock—to prevent the frame from wracking.[13]

New York Chairs: Some Distinguishing Features

Documentary and material evidence indicates that New York artisans made leather chairs in imitation of Boston and English seating, at least for a while. From 1700 to 1710, New York merchants such as Benjamin Faneuil and Abraham Wendell imported and sold large numbers of Boston leather chairs. Such chairs would have provided ready design sources for local artisans. Huguenot chairmaker Richard Lott purchased at least one set of carved-top leather chairs from Thomas Fitch. Lott probably intended to sell the chairs, but he may also have used them as models. When New York chairmakers copied imported examples, they did so within the context of their own craft traditions. Their turning patterns and construction methods thus differ significantly from those utilized by their Boston counterparts (figs. 19, 20).

On New York chairs, the turned baluster just above the seat is shallow (figs. 19, 20), whereas on Boston chairs this turning is more robust (fig. 1). The upper turnings of the back posts also differ depending on the chair’s origin. Boston chairs have columns ending in reels, whereas New York chairs have more classically correct, quarter-round capitals; furthermore, none of the chairs that the authors attribute to New York incorporate the standard “Boston” stretcher. Instead, most “plain top’d” New York chairs have a block and turned front or medial stretcher with an extra ball just inside the block (fig. 21).[14]

Another critical distinction between Boston and New York chairs can be seen in the joinery of the frame. When New York chairmakers constructed trapezoidal seats, they left the leg blocks square and planed away only the outside edge in order to align it with the side stretchers (fig. 22). As a result, the side stretchers connect to the rear legs and front legs at oblique angles, and the front stretcher blocks do not overhang on the back sides, as they do on Boston chairs. The rear legs of New York chairs are also square and unchamfered rather than being shaped like those of figure 18. All of these features are present on the side chairs illustrated in figures 19, 20, and 23.

The turning details and construction methods are also different on armchairs from the two regions. The armchair shown in figure 24 is constructed in the New York manner, whereas the one in figure 25 is constructed in the Boston manner. The latter armchair has a 14 1/2" “Boston” rear stretcher identical to the front stretchers illustrated in figure 6. That the same stretchers could be used on both side chairs and armchairs is another example of the efficiencies achieved by Boston artisans. The two armchairs also have different rear posts, medial stretchers, and arm supports. The urn and baluster supports of the New York armchair (fig. 24) are related to the turnings on contemporary gateleg tables from that city (fig. 26).[15]

One intriguing parallel between these armchairs (figs. 24, 25) and the side chairs illustrated in figures 10 and 23 is that the carving on their crests and their front stretchers is remarkably similar. Assuming that the chairs shown in figures 10 and 25 are Boston made and the other two chairs (figs. 23, 24) are New York made, one explanation for this similarity is that a Boston carver exported piecework to New York; however, no documentary evidence of this practice has been located. Another possibility is that a carver moved from one city to the other. A New York armchair that descended in the Van Cortlandt family (fig. 27) has related carving, but it appears to be by a different hand. The carving on the Van Cortlandt chair, which is somewhat less accomplished, probably represents the work of a local tradesman. The turnings and stance of the Van Cortlandt armchair differ from the other New York seating included in this study; however, it has square legs rather than chamfered ones like contemporary Boston chairs.

The predecessors of these New York leather chairs also differed from their seventeenth-century Boston counterparts. Although seventeenth-century New York chairs are exceedingly rare, an unusual turned and joined armchair shows several departures from standard Boston construction (fig. 28). The seat is trapezoidal rather than square like those of Boston low-back chairs (see fig. 2), and the side rails join the square legs at oblique angles in the New York manner. In addition, the front stretcher relates directly to the side stretchers of a late seventeenth- or early eighteenth-century New York escritoire (at the Metropolitan Museum of Art). The meticulous stock preparation and joinery of the chair contrasts with contemporary Boston chairs, many of which were mass-produced objects made for a burgeoning local market and the export trade. Slight variations in the turnings on individual Boston chairs suggest that specialists turned the legs and stretchers while others assembled chairs from bins of parts. Often the seat and side rails (generally of red oak) bear signs of being riven and dressed hurriedly.[16]

Boston chairmakers’ efforts to expedite production may explain why the widths of their side stretchers vary so much. Within fairly wide tolerances, Boston makers could use whatever stock was on hand. When thin stock was available, the stretchers could have barefaced tenons, but when a wider piece was handy a second shoulder could be added. Or, when the stretcher width was not sufficient to allow a full second shoulder, the chairmaker simply cut one shoulder narrower than the other. New York makers were much more precise and more regimented in their production methods. On the side chairs illustrated in figures 19, 20, and 23, the side stretchers are dressed to a uniform thickness of 3/4", and they have barefaced tenons that are 3/8" thick.

The ledgers and letterbooks of Thomas Fitch document numerous shipments of Boston leather chairs to New York between 1700 and 1720. In 1706, Fitch wrote Benjamin Faneuil, “I would have sent yo some chairs but could scarcely comply with those I had promised to go by these sloops.” Given the date of this letter, it is likely that Fitch was referring to first-generation chairs. Boston merchant-upholsterers, such as Fitch, purchased chairs from several different chairmakers, who in turn commissioned piecework from turners, carvers, and other specialists. The New York chairs discussed above suggest that tradesmen in that city mounted a brief response to Boston imports during the first decade of the eighteenth century; however, the development of faster and less expensive methods of production in Boston—manifest in the turnings and construction of second-generation chairs—and that city’s expanding venture cargo trade evidently stifled the competition in New York. This would explain why there are no New York versions of fully developed, single-side-stretcher, second-generation Boston chairs.[17]

The Perils of Relying on Provenance

Considering the vast quantity of seating imported by merchants such as Faneuil and Wendell, a New York provenance is insufficient for determining a leather chair’s origin; nevertheless, in attributing Winterthur’s first-generation Boston chairs to New York, Forman relied heavily on the oral history of the side chair illustrated in figure 29. The chair reportedly belonged to artist Pieter Vanderlyn, who immigrated to New York City in 1718. If Vanderlyn owned the chair, he undoubtedly purchased it secondhand. Not only does the chair have a “Boston” stretcher, but its construction, double side stretchers, and complex post turnings suggest that it predates Vanderlyn’s arrival by about a decade. Many chairs that are clearly of Boston origin have eighteenth-century histories in New York, and some even bear the initials of successive New York owners. In light of all this, Forman’s extrapolation of a New York origin for Winterthur’s first-generation chairs, using the history of the Vanderlyn chair, is unpersuasive.[18]

By contrast, a Boston-area provenance for a first-generation chair is meaningful, since there is virtually no evidence of leather chairs being imported there from any other colonial port. A side chair with a “Boston” front stretcher and first-generation construction details (fig. 30) has a nineteenth-century label that reads, “This chair belonged to Rev. Thomas Potwine born in Boston Oct. 8, 1731, ordained E. Windsor May 1, 1754. Died November 15, 1802 . . . by E. Simons.” Simons owned the chair and its mate (at the Yale University Art Gallery) prior to 1891, when Irving Whitehall Lyon illustrated one in The Colonial Furniture of New England. Although the label does not prove that the chair originated in Boston, it adds to the circumstantial evidence. Similarly, several second-generation details occur on a couch advertised in the March 1984 issue of Antiques and labeled: “Bed belonged to Rev. Daniel Shute, D. D. (1722–1802) of South Hingham, Mass., ordained pastor in Hingham in 1746.” The couch has an arched “Prince of Wales” crest similar to those illustrated in figures 14 and 15, elongated columns, scored cylinders above the seat, and raked rear legs. The only Boston construction detail missing is the chamfering on the legs, which is unnecessary because of the long rectangular seat. All of these details point to a Boston origin, as the label suggests.[19]

Although the majority of the chairs examined by the authors fit neatly into the structural and stylistic paradigms established for Boston and New York, a few have disparate features. A pair of side chairs recently discovered in Maine (fig. 31) are similar to first-generation Boston chairs (see. fig. 1), but their turnings are less sophisticated and more indicative of rural work. As Randall suggested, Boston-trained artisans who moved to the Piscataqua region probably made such chairs for a short period of time. Eventually, however, they undoubtedly succumbed to the competition from Boston imports, just as their counterparts in New York, Philadelphia, and other regions of colonial America did.[20]

The evidence presented here clearly shows how first-generation Boston chairs relate to the seating forms that both preceded and followed them. These first-generation chairs would be completely out of context if they were constructed in New York. Changing fashions affected turning styles and basic chair forms, but most of the structural modifications that occurred in Boston seating between 1700 and 1720 reflect efforts to expedite production, reduce cost, and achieve a more elegant vertical look. The account books and letterbooks of Fitch and his apprentice Samuel Grant (fl. independently ca. 1728), colonial shipping records, and other documentary sources indicate that Boston artisans and their merchant-patrons produced vast quantities of chairs and dominated the coastal trade in seating until the mid-eighteenth century. The assertion that New York mounted a successful response to Boston imports is incompatible with this evidence and distorts the history of colonial industry and commerce.[21]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article, the authors thank Mark Anderson, Jean Blair, Allison Perkins Brown, Nannie W. T. Brown, Jonathan Fairbanks, Benjamin Faucett, Patricia E. Kane, Peter M. Kenny, John T. Kirk, Mario Martinez, Henry Merriman, Richard Stevenson, and Wayne Utley.

For examples of Boston easy chairs, see Forman, American Seating Furniture, pp. 363, 367; advertisement by John Walton, Inc., Antiques 120, no. 2 (August 1981): 206. Roger Gonzales first recognized the “Boston” stretcher. He also developed the chronological framework for the Boston seating presented here and was the first to observe the distinctive stylistic and structural details of the New York chairs illustrated in figs. 19, 20, and 23.

For an English or Dutch chair with a leather back and slit crest rail, see fig. 8. A late seventeenth-century side chair with a slit, carved crest rail, hollow back, carved stretcher, and “barley-twist” front legs, stretchers, and rear posts is illustrated in Oswaldo Rodriguez Roque, American Furniture at Chipstone (Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press, 1984), p. 107. This chair reportedly descended in the Pritchard family of Milford, Connecticut. As quoted in Forman, American Seating Furniture, p. 283.

For seventeenth-century, English low-back armchairs with single side stretchers, see Kirk, American Furniture and the British Tradition, p. 221, fig. 676; and Victor Chinnery, Oak Furniture: The British Tradition (Woodbridge, England: Antique Collectors’ Club, Baron Publishing, 1979), p. 278. For a Boston example, see Fairbanks and Trent, eds., New England Begins, 3:532–33.

Forman, American Seating Furniture, p. 301, fig. 169, shows a detail of two Boston chairs with undercut blocks and reel-shaped capitals. New York chairs have more attenuated post turnings than Boston examples, but the space between the seat rail and the lower back rail is about the same. Because New York turnings occupy more of the vertical space, there is less room for the square stock of the back leg; thus, the turning shapes and size of the exposed blocks beneath them can help verify a chair’s New York origin. Similar columns appear on other examples of New York furniture (see the ca. 1700 escritoire in Marshall B. Davidson and Elizabeth Stillinger, The American Wing at The Metropolitan Museum of Art [New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1985], p. 108). The extra ball on New York stretchers is also found on turned elements of New York tables from that period. See Peter M. Kenny, “Flat Gates, Draw Bars, Twists, and Urns: New York’s Distinctive, Early Baroque Oval Tables with Falling Leaves,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1994), p. 122.

New York’s chairmaking community was considerably more diverse than Boston’s and included artisans of English, French, and Dutch descent (see Forman, American Seating Furniture, pp. 321–24; and Kamil, “Hidden in Plain Sight”).

Forman, American Seating Furniture, pp. 292, 285. As quoted in Kamil, “Hidden in Plain Sight,” p. 196. Although the New York chairs have double side stretchers like first-generation Boston chairs, the authors believe the New York examples shown in figs. 19 and 20 are contemporary with second-generation Boston ones. This would explain why the turnings on New York chairs sometimes bear more resemblance to Boston second-generation chairs.

Forman, American Seating Furniture, p. 326. The Vanderlyn chair is also attributed to New York in Robert F. Trent, “The Early Baroque in Colonial America: The William and Mary Style,” in American Furniture with Related Decorative Arts 1661–1830: The Milwaukee Art Museum and Layton Collection, edited by Gerald W. R. Ward (New York: Hudson Hill Press, 1991), pp. 68–69. For other Boston chairs with New York histories, see Joseph T. Butler, Sleepy Hollow Restorations: A Cross-Section of the Collection (Tarrytown, N.Y.: Sleepy Hollow Press, 1983), p. 53; Failey, Long Island is My Nation, p. 26, fig. 23; and Roderic H. Blackburn, “Branded and Stamped New York Furniture,” Antiques 119, no. 5 (May 1981): 1131.

The Potwine family originated in Boston and resided briefly in Hartford before settling in Coventry, Connecticut, about 1740. There is no evidence that Thomas Potwine had any ties to New York (Franklin Bowditch Dexter, Biographical Sketches of the Graduates of Yale College with Annals of the College History: October, 1701-May, 1745 [New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1885], pp. 265–66). Irving Whitehall Lyon, The Colonial Furniture of New England (1891; reprint ed., Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1925), p. 171, fig. 69. The Yale chair is illustrated in Patricia Kane, 300 Years of Seating Furniture (Boston: New York Graphic Society, 1975), pp. 60–61. The couch is illustrated in an advertisement by Bernard & S. Dean Levy, Inc., Antiques 125, no. 3 (March 1984): 492.