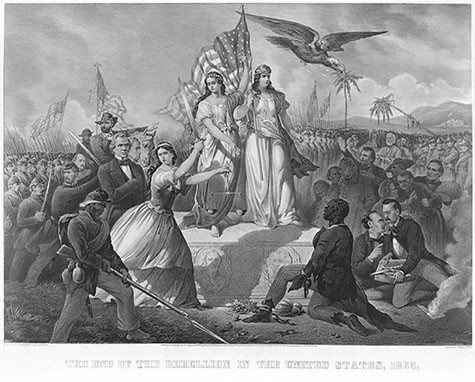

Charles Kimmel, The End of the Rebellion in the United States, New York, 1865. Lithograph printed in black and green olive on woven paper. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.)

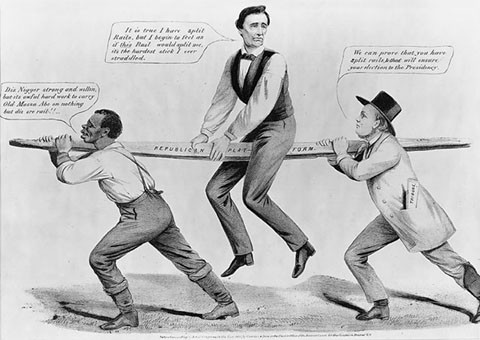

The Rail Candidate, attributed to Louis Maurer and published by Currier & Ives, New York, 1860. Lithograph on woven paper. (Courtesy, Library of Congerss.)

David Hunter Strother, The Horse Camp in Dismal Swamp, North Carolina, 1865. Ink wash on beige paper. (Private collection; photo, Andre Lovinescu.)

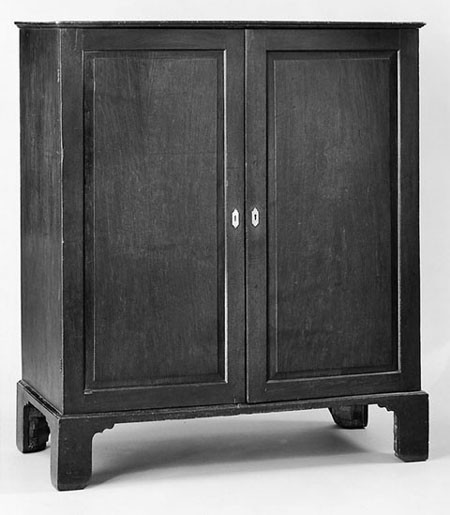

Cupboard, Amherst County, Virginia, 1760–1840. Oak. H. 66 1/4", W. 25 1/2", D. 11 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

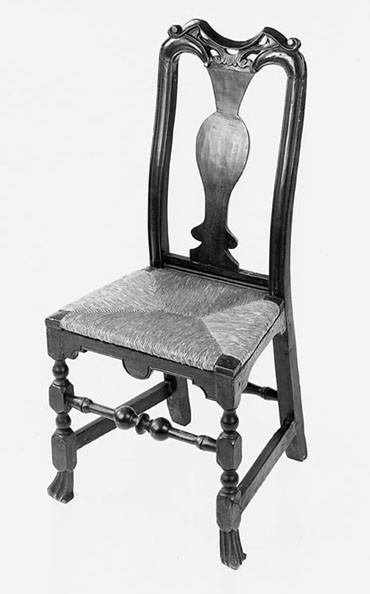

Side chair, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1725–1740. Maple. H. 40 1/2", W. 18", D. 18". (Private collection; photo, Douglas Armsden.)

Benjamin Bucktrout, Masonic master’s chair, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1766–1777. Mahogany with walnut; painted and gilded ornament, original leather. H. 65 1/2", W. 31 1/4", D. 29 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

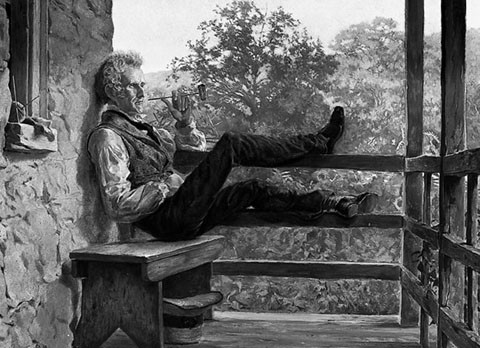

Francis Blackwell Mayer, Independence, Squire Jack Porter, Frostburg, Maryland, 1858. Oil on millboard. (Courtesy, National Museum of Art.)

William Sidney Mount, Cider Making, Stony Brook, New York, 1841. Oil on canvas. (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Bequest of Charles Allen Munn, by exchange, 1996 (66.126) Photograph ©1983 The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Robert Brammer and Augustus A. Von Smith, Oakland House and Race Course, Louisville, Kentucky, 1840. Oil on canvas. (Courtesy,J. B. Speed Art Museum.)

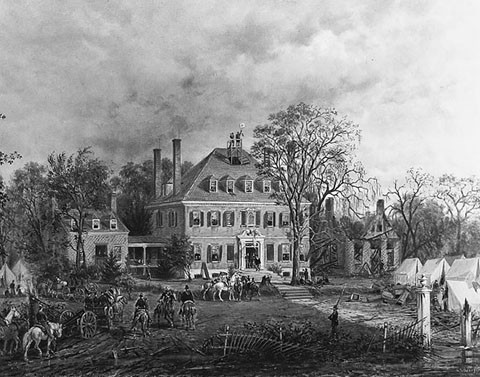

Edward Lamson Henry, The Old Westover Mansion, Charles City County, Virginia, 1869. Oil on panel. (Courtesy, Corcoran Gallery of Art.)

Side table, northeastern North Carolina, 1780–1800. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 29", W. 37 1/4", D. 27". (Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

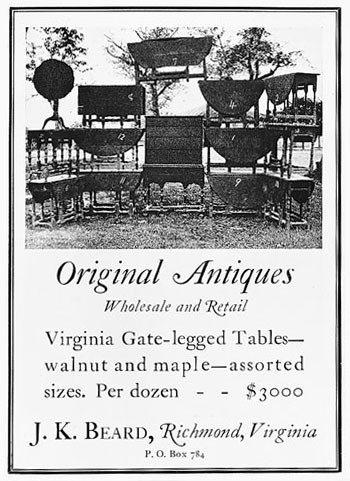

Advertisement by J. K. Beard of Richmond, Virginia, in Antiques 4, no. 4 (October 1923): 193.

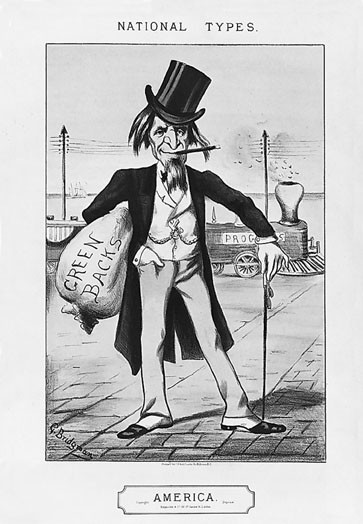

Bridgman, America, lithograph (hand-colored), ca. 1880, 11 3/4 x 7 13/16 inches. (Courtesy, Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas.) 1974.45

Clothespress, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1760–1770. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 56 5/8", W. 49 1/2", D. 23". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

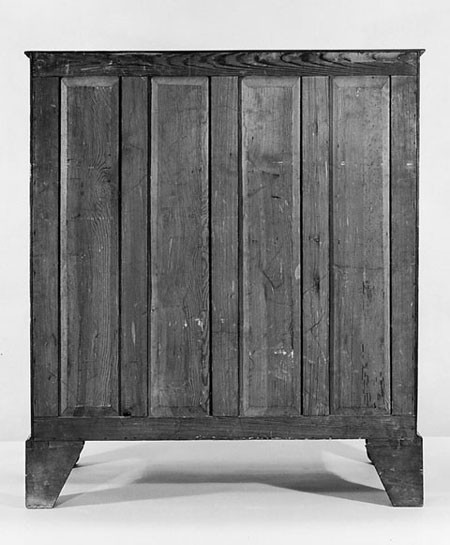

Detail of the paneled back of the clothespress illustrated in fig. 14.

Chest of drawers, Boston, 1770–1780. Mahogany with white pine. H. 32 1/8", W. 35 3/4", D. 21". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

Detail of the interior construction of the chest illustrated in fig. 16.

Dressing table, Boston, 1735–1750. Walnut, walnut veneer, and birch with white pine. H. 32 1/4", W. 33 3/8", D. 21 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

John Selden, clothespress, Norfolk, Virginia, 1775. Mahogany with yellow pine and mahogany. H. 74 1/4", W. 50 1/8", D. 23 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

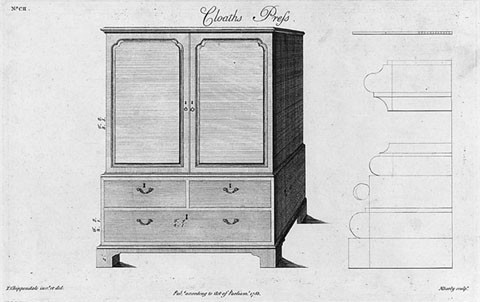

Design for a clothespress on plate 129 in the third edition of Thomas Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1762). (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Alexander Spotswood Payne and his brother, John Dandridge Payne, with their Nurse, attributed to the Payne Limner, painted at New Market, Goochland County, Virginia, 1790–1800. Oil on canvas, 56"H x 69"W (©Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. Gift of Miss Dorothy Payne. Photo, Linda Loughran)

Side chair attributed to Thomas Day, Milton, North Carolina, ca. 1850. Mahogany, walnut, rosewood, and mahogany veneer with tulip poplar. H. 35 1/2", W. 17 3/4", D. 16". (Courtesy, North Carolina Museum of History.)

Chest of drawers, probably Shenandoah County, Virginia, 1794. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 67 3/4", W. 41 1/4", D. 23". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Hans Lorenz.)

For generous helpfulness in bringing the material together, [thanks] to Miss Sophie Harrill, of Knoxville, who, having become resentful of Northern insinuations as to the preponderance of pineapples among antiquities of the South, has undertaken to furnish proof of the existence of far finer fruits of early craftsmanship below the Mason Dixon Line.

—Antiques, January 1927

This volume of American Furniture is comprised of essays presented at “A Region of Regions: Cultural Diversity and the Furniture Trade in the Early South,” a 1997 symposium cosponsored by the Chipstone Foundation and the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Together with the publication of Southern Furniture, 1680–1830: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection and its accompanying exhibition, these essays bring much-needed attention to an American regional craft tradition that for the most part has received only parochial notice. By revealing the unexpected multicultural flavor of the region, these studies also point toward new directions in American furniture scholarship, notably in the areas of regionalism and material culture methodology. On a more theoretical level, these publications challenge time-honored assumptions about American furniture and, in doing so, subvert popular notions about American history and culture.

My essay will suggest a new interpretive framework upon which to ground recent southern material culture scholarship. More specifically, it will explore and critically reassess the “Idea of the South,” which not only shapes conventional American furniture analysis but also fundamentally informs popular interpretation of American history. Two main themes will be forwarded. The first suggests that southern furniture scholars need to recognize and, when necessary, respond to cultural generalizations that are poorly informed or deliberately fictive. New publications and exhibitions of new studies will help counterbalance the narrow focus of conventional decorative arts literature. Quantity alone, however, will not reshape deeply entrenched cultural notions, notably, the common tendency to portray the early North and, in particular, New England as normative and the early South as deviant. American popular history traces the roots of national identity to the Puritans who landed at Plymouth Rock in 1620, not to the Virginians who founded Jamestown more than a decade earlier. Such interpretive imbalances, in turn, suggest a reconsideration of popular ideas about the South that reflect “distorted cultural stereotypes and even exaggerated caricatures of the mythic entity that can mislead and misinform.”[1]

Paradoxically, the second part of this essay proposes that significant insight can emerge from a closer inspection of certain lasting ideas about regional identity. This strategy entails looking not at what northerners and southerners were but rather at what residents of both regions perceived the North and South to be. Thus, while scholars need more thoughtfully to contextualize prejudicial characterizations of the South they also need to recognize the power of popular regional depictions to reveal hidden truths that can offer valuable insight into early American material culture.

The inferior status of southern furniture in the American decorative arts world has many causes. To be sure, much of the blame lies with early American collectors, dealers, and scholars who equated the South’s agrarian character with an inability to engage in sophisticated or large-scale furniture production. Yet, their viewpoint represents less a cause than a symptom of the minimal consideration of southern furniture. Even more significant is a particular moment in time—one that is universally recognized by historians but rarely mentioned by decorative arts enthusiasts. On April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Courthouse in Virginia, General Robert E. Lee signed terms of surrender ending the four-year conflict between the Confederate States and the Union. More than just the end of the Civil War, this date marks the very instant when the cultural perspective of the white South was effectively rendered illegitimate (fig. 1). (The perspective of the black South never even attained widespread recognition.) Not content with the demographic, economic, and political gains that came with victory, northern leaders sought to fundamentally reconfigure the South. Expressing a typical view, Senator Thaddeus Stevens, a prominent reconstructionist, called for a total reform of the region: “The foundation of their institutions—political, municipal, and social—must be broken up. This can only be done by treating and holding them as a conquered people.”[2]

Post–Civil War popular history plainly reflects the overwhelming success of the North’s cultural triumph. Explained one staunch defender of the Old South, “The North defeated the South in war, crushed and humiliated it in peace, and waged against it a war of intellectual and spiritual conquest.” The victors earned the right to redefine and reshape the American story, which ever since has been filtered through a northern lens and colored to satisfy northern sensibilities. As a consequence, general understanding of the American past is incomplete and, instead, mirrors Winston Churchill’s war aphorism that “The victors forget, the vanquished remember.”[3]

Even the most rudimentary historical assumptions reflect how the distinction between fact and fiction is blurred to create a morally palatable national narrative. We need only look at common attitudes about the Civil War. General Ulysses S. Grant and other northern military and political leaders are justly cited for their help in ending the atrocity of slavery. On the other hand, popular history conveniently forgets that some of these northern leaders, including Grant, were slave owners, while a number of key southern military leaders, including General Lee, publicly denounced the institution. Portrayals of President Abraham Lincoln are similarly skewed. Although widely hailed in historical lore as a progressive social reformer and leader in the fight to end slavery, Lincoln was actually a staunch social conservative who in 1860 was elected president of a slaveholding republic and whose campaign platform unmistakably defended the individual rights of the slave states. Deleted from popular memory is Lincoln’s profound discomfort with the idea of freeing slaves, whom he wanted to “return” to Africa; indeed, the author of the Emancipation Proclamation once informed a group of African-American leaders that “in this broad continent not a single man of your race is made the equal of a single man of ours . . . it is a fact . . . it is better for us both, therefore, to be separated” (fig. 2).[4]

Of course, historical revisionism of this sort resonates discordantly within our collective national consciousness and undermines traditional characterizations about the progressive North and the backward South (fig. 3). These examples are not meant, however, to rekindle centuries-old interregional antagonisms nor to mitigate in any way the human tragedy of the South’s “peculiar institution.” Instead, these examples validate Churchill’s adage that history is not a fair game. On April 9, 1865, the North earned the right to reconfigure the American story. In the decades that followed, northern scholars, dealers, collectors, and curators laid the conceptual foundations for an American furniture story, which fully realized de Toqueville’s prophesy that “the civilization of the North appears to be the common standard, to which the whole nation will one day be assimilated.” Still largely intact today, the American furniture story is centered around the same regional hierarchy that defines popular history. Here, regionalism acts as a metaphor for the construction of national identity, and the “Americanness” of a given furniture form is measured in terms of its allegiance to accepted, northern standards.[5]

For more than one hundred years, private and institutional collections, exhibitions, and publications have claimed to present the topic of “American furniture.” Few, however, allude to southern craft traditions. When the South is included, the resulting analysis is based more on common myth than on demonstrable fact. Portrayals of the region, although of diverse flavor, inevitably lead back to one familiar theme: the South as a culturally impaired place (fig. 4). In the American furniture story, southern furniture exists less as an accepted regional craft tradition than as a chronic interpretive problem. Examples of this perspective range from Rachel Raymond’s observation in the December 1922 issue of Antiques that no evidence survives to indicate any southern furnituremaking legacy; to Joseph Downs’s infamous declaration at the 1949 Williamsburg Antiques Forum that little of artistic merit was made south of Baltimore; to Morrison Heckscher and Leslie Greene Bowman’s undocumented hypothesis in American Rococo (1992) that early southern furniture primarily represents the “part-time work of farmers.” Similarly shaded is an American furniture connoisseurship that describes a stylistically confused New England chair (fig. 5) as “harmonious” but refers to an important southern Masonic master’s chair as lacking “total coherence” (fig. 6). Echoing a common assumption about southern furniture, the criticism of the master’s chair alludes to “aesthetic shortcomings,” including poorly conceived arm supports, oversized pilasters, and decorative motifs that “cling to the sides of the openwork back as if tossed into a magnetized box.”[6]

Popular generalizations about the cultural illiteracy of the early South cumulatively have functioned as a kind of public anaesthetic, limiting inquiry into southern craft traditions. The authors of this volume of American Furniture seek to redress the interpretive imbalance by building upon the pioneering research of Paul Burroughs, E. Milby Burton, and Frank Horton, and the subsequent work of John Bivins, Wallace Gusler, Brad Rauschenberg, Sumpter Priddy, Gregory Weidman, Luke Beckerdite, and others. By focusing on the rarely acknowledged cultural diversity of the region, this scholarship reexamines and substantially redefines the traditional historical roles assigned to southern wares and artisans. Even so, significant obstacles remain in the form of certain lingering cultural assumptions. To move beyond these obstacles and overcome the perceived problem of southern furniture, we need to delve further into the “Idea of the South” and, specifically, to reconsider the historical and mythological character of the region. Such an approach promises to clear the way for more thoughtfully contextualized interpretations of the region’s diverse material culture traditions.

What does it mean to say “the South” or to describe something as “southern”? In American popular history, these otherwise neutral regional terms are culturally charged. Unlike any other region, the South exists in a different realm and is subject to a different type of historical interpretation. As historian Larry Griffen notes, the South invariably is linked to chronic problems of economy, racism, and social difficulties. In other American regions, however, equally significant shortcomings—including the treatment of Native Americans, non-Anglo immigrants, and women, and issues surrounding child labor, urban blight, and ghettoization—are not similarly scrutinized. Only in the South are the problems equated with the region as a whole.[7]

Historian C. Van Woodward suggests that this skewed perspective is even more evident when the South is viewed through the lens of comparative history. America, despite select regional deficiencies, invariably is portrayed as a great success story. The South, on the other hand, is distinguished by a long litany of failures. Whereas America is depicted as a land of opportunity, progress, and prosperity, the South represents a land of poverty, frustration, and failure. The distinctive identity of the South additionally is grounded in the un-American experience of defeat and submission, not only in the military arena but also in the economic, social, political, and philosophical realms. Finally, even the region’s self-conscious allegiance to premodern European cultural traditions digresses from the celebrated myth of American innocence, which idealizes the settlers’ escape from the sinful Old World and subsequent creation of a productive New World.[8]

Woodward’s reading of the South, while not complete, does hint at crucial regional differences not included in the telling of the American story, which casts the South in the shadow of northern cultural achievement. Fundamentally, the early South diverged from the North in its faithful adherence to a broad spectrum of Old World Christian and cultural traditions. The region’s conservative social and political ideology and its adoption of a decentralized and minimally interventive governmental structure reflect this orientation; so, too, do the familiar Jeffersonian ideals of private virtue and individual liberty (fig. 7). Southern culture especially resembled premodern Europe in its fundamental reliance on the land—an orientation that provided a shared form of life and common language for white planters, and a tragically common American experience for slaves. Beyond the obvious demographic differences associated with the pervasive agrarian orientation, the South diverged from the North in many other ways as well. Historian Mechal Sobel argues that the essence of a culture is reflected in its sense of time. In the face of the emerging northern capitalist model, late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century southerners differed in their ideas about time and time management. In the slave-powered agrarian South, time was regulated less by mechanical clocks than by the rhythms of nature, a pattern that subsequently inspired widespread northern mythologizing about the “leisurely” and “lazy” character of the South.[9]

After 1790, mounting regional differences in the form of industrialization, improved transportation networks, faster lines of interregional communication, national educational reform, and, later, abolitionalism brought about a highly fertile period in the evolution of southern and northern mythic identities. In the eyes of outsiders, the South’s conservative ways became equated with cultural backwardness and regarded as contrary to progressive national values. American character instead was linked to blossoming ingenuity, productivity, and industry—attributes invariably associated with northern culture and esteemed in opposition to southern social and economic conservatism (fig. 8).

Not surprisingly southern elites saw these national and regional developments from a different perspective. In the preface to Swallow Barn, a novel written as a rebuttal to the rising tide of abolitionist literature, John Pendleton Kennedy lamented:

An observer cannot fail to note that the manners of our country have been tending towards a uniformity which is visibly effacing all local differences. The old states, especially, are losing their original distinctive habits and modes of life, and in the same degree, I fear, are losing their exclusive American character.

White southerners increasingly adopted a kind of fortress mentality and defended the full spectrum of the region’s cultural traditions. Echoing the reactionary flavor of many southern newspapers and magazines, Kennedy wrote:

[The southerner] thinks lightly of the mercantile interest, and, in fact, undervalues the manners of the large cities generally. He believes that those who live in them are hollow-hearted and insincere, and wanting in that substantial intelligence and virtue, which he affirms to be characteristic of the country.

Within the South’s increasingly self-conscious definition of its own regional identity emerged the fully evolved southern “Cavalier,” a mythic figure steeped in honor and integrity, indifferent to money and business, and imbued with a high sense of social decorum and civic awareness. This image brings to mind Jefferson’s “natural man”—part planter, part aristocrat, part hunter, and part horseman—whose benign yet self-indulgent lifestyle fueled characterizations of a South that “at its best is relaxed; at its worst is either asleep or frenzied” (fig. 9).[10]

Given the general exclusion of southern cultural perspectives, however, the South of American popular history ultimately must be understood as a kind of cultural fiction that, in many ways, would be unrecognizable to early American eyes. Defined less as an actual place with its own historical legacy than as a lingering idea or belief, the South is distinguished by its long-standing opposition to basic American values and exists as a blight on the cultural and political landscape. This mythic region assumes an exhaustive range of guises: the Savage South, the Plantation South, the Proslavery South, the Redneck South, the Demagogic South, the States Rights South, the Bucolic South, the Regressive South, the Intolerant South, the Evangelical South, the Aberrant South, and the Lazy South. Especially familiar is the “Old South,” a term so frequently and carelessly applied that it now is largely devoid of any cultural or symbolic meaning.[11]

Each of these images of the South has some basis in reality, yet none alone tells the whole tale (fig. 10). Moreover, given the dominant northern cultural orientation of popular history, we also need to recognize the source of many of these persistant images. While southern apologists such as Kennedy, William Wirt, and John C. Calhoun contributed to our popular understanding of southern character, we must also finally acknowledge the enormous fictive contributions of northerners such as writers Harriet Beecher Stowe and William Lloyd Garrison, and musicians David Christy, Stephen Foster, and Dan Emmett, who penned the song “Dixie” in 1859. In his novel Intruder in the Dust William Faulkner elaborated on the North’s seemingly limitless fascination with the South, and in particular its “volitionless, almost helpless capacity and eagerness to believe anything about the South not even provided it be derogatory but merely bizarre and strange enough.” The same gullibility has long guided conventional analysis of southern furniture and still informs the common assumption that southern wares are proportionally and decoratively abnormal—a perspective embodied in the description of a North Carolina demi-lune table as burdened by “unusual, heavy moldings” and “massive construction techniques” (fig. 11).[12]

Given their complex origins, popular ideas about American regional character need to be more closely scrutinized to evaluate their historical validity and interpretive usefulness. Toward this end, historian David Smiley argues for reconsideration of the “Idea of the South,” a conceptual abstraction that nevertheless represents a crucial historical reality upon which people acted, risked, and even died. Historians Patrick Gerster and Nicholas Cords likewise claim that historical reality not only encompasses what can be directly proven but also what is believed to be true. The authors specify two dominant approaches to American mythology. The first perspective—one that is all too easily adopted by southern decorative arts scholars—stresses the negative aspect of myth. This attitude is epitomized in the words of Thomas Bailey, who concludes that “a historical myth is . . . an account or belief that is demonstrably untrue, in whole or substantial part.” More informative, however, is a second perspective that centers around Henry Nash Smith’s belief in the culturally unifying aspect of myth as “an intellectual construction that fuses concept and emotion into an image.” Viewed in this light, popular generalizations about regional identity can hint at certain cultural truths about both the South and the North and offer a way to move past the time-worn debate about whether southerners are “racist baboons or the true heirs of Aristotle” toward the more important consideration of how such opinions came to be formed.[13]

The potential for popular history to inform material culture analysis remains an open area for investigation. For instance, intriguing parallels link the changing character of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century ideas about the South to emerging attitudes about American decorative arts. Historian George Tindall notes that, after 1880 or so, Americans became captivated with the South. This change of heart largely reflected a sympathetic reaction to the perceived inequities of Reconstruction, as well as a rise in nostalgic southern romances and a recognition of the New South with its social and political emulation of northern norms. But, the 1920s saw the reemergence of a markedly different perspective, what Tindall calls a “kind of neoabolitionist myth of the Savage South.” Placed back into the national spotlight were a wide range of southern problems, including lynching, child labor, the Scopes trial, poor education, and endemic health problems—a critical viewpoint that can be traced not only to the writings of unapologetic cultural observers such as H. L. Mencken but also to introspective southern literature such as William Faulkner’s Sanctuary. The national criticism was so great that it fueled a coordinated and, as during the antebellum era, reactionary southern response, embodied in the widely read Agrarian manifesto I’ll Take My Stand and the historical scholarship of Wilbur J. Cash and Ullrich B. Phillips.[14]

Parallel changes characterize decorative arts trends of the same period. In their eagerness to identify important early furnituremaking traditions, late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century furniture scholars were responsive to southern as well as to northern material culture. Although unmistakably inclined toward the superiority of northern traditions, authors nevertheless explored objects that crossed a wide range of regional and class lines. Wallace Nutting, a highly influential furniture scholar and entrepreneur, illustrated many southern furniture forms in his Furniture Treasury (1928). Likewise, early issues of Antiques (first published in 1922) reflect a decidedly democratic vision of early American artisanry, and many of the articles, queries, and advertisements center around southern themes (fig. 12). By the late 1920s, however, this egalitarian focus gave way to the formal creation of a northern-based American furniture canon. Popular understanding of the American furniture story was reshaped by a series of influential exhibitions and sales, for example the establishment and subsequent expansion of the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art during the mid-1920s, the sale of the Reifsnyder (1929) and Flayderman (1930) collections, and the growing dominance of northern antiques dealers.

A reconsideration of common assumptions about American regional identity reveals other new material culture perspectives. In opposition to the Cavalier we find the Yankee, a figure who in post–Civil War popular history frequently possesses the transcendent qualities of curiosity, asceticism, and single-mindedness. But this mythic incarnation, particularly conspicuous in the novels of Horatio Alger, was not universal, even among northerners. In the face of rising urbanization and industrialization, nineteenth-century New Hampshire social critic and novelist Sarah Josepha Hale nostalgically longed for lost Puritan values. She argued that the founding ideals of spirituality, community, and the Protestant ethic were being subsumed by new liabilities of the northern character and by the growing tendency toward selfish acquisitiveness and predatory greed (fig. 13). Even more critical were non-northerners, whose observations rarely appear in the telling of the American story. A Scottish visitor to New England in 1833 noted:

The whole race of Yankee peddlers, in particular, are proverbial for their dishonesty. They warrant broken watches to be the best time-keepers in the world; sell pinch-beck trinkets for gold; and have always a large assortment of wooden nutmegs and stagnant barometers.[15]

In this light, the Yankee character of New England furniture can be seen anew. Even a cursory consideration of eighteenth-century New England furniture, in particular urban wares, reveals a kinship with the parsimonious Yankee spirit. A penny-pinching mentality seems linked to the common regional craft practice of minimal and, at times, blatantly cheap case construction. Unlike many southern makers—who emulated sophisticated British construction in the use of structurally reinforcing dustboards, composite foot and drawer blocking, and floating-panel drawers and case backs (figs. 14, 15)—New England artisans often took a far less meticulous approach. On even the largest case furniture forms, drawers are often tenuously supported by thin, nailed-on runners, which have the additional flaw of restricting the normal seasonal expansion and contraction of the case (figs. 16, 17). Furthermore, the Yankee mindset is echoed in the carefully veiled substitution of inexpensive materials. Although there may have been legitimate regional shortages of good timber, the insertion of stained-maple rear rails on mahogany and walnut chairs is an excessively frugal shortcut by any standard, as perhaps is the artful insertion of stained birch cabriole legs on some early walnut case pieces (fig. 18).[16]

At the same time, the mythic Yankee serves as a foundation upon which to compliment New England furniture. The blossoming, post-Revolutionary northern preoccupation with material gain and upward social mobility may well have worked alongside the conservative New England retention of local craft traditions to create that region’s many wonderfully expressive furniture forms. For many prosperous New England merchants, shapely bombé, serpentine, and blockfront case pieces served as requisite symbols of wealth and social status (see fig. 16). Ultimately, the interpretive purview of American material culture analysis needs to recognize all sorts of evidence. In the case of early northern furniture we should pay attention to traveller John Kirke Paulding’s observations about his own northern identity. In Letters from the South, Written During an Excursion in the Summer of 1816, Paulding commented:

I have heard it often remarked in our part of the world, with great self complacency, by portly traders and brokers, who fancied themselves at the pinnacle of refinement, because they had a splendid equipage and fine furniture; “that the middle and eastern States were at least a century before the southern, in refinement and civilization.” Upon inquiring into the grounds of this notion, I found it uniformly originated in the vulgar practice of confounding mere personal comforts, and little domestic knick-knackery with the qualities of the mind, or the exercise of the intellectual faculty. Thus, in the eyes of stupidity, the fine coat makes the gentleman, all over the world.

Perhaps eye-catching New England furniture worked as well as a “fine coat.”[17]

Southern material culture, as with early southern culture in general, is usefully seen in opposition to northern precedent, but we first need to overcome the prevalent decorative arts tendency to mimic the biases of American popular history. At best, the stylistic simplicity of southern furniture is seen as evidence of the region’s agrarian character and lack of large-scale urban centers; at worst, the austerity of southern furniture is cited as proof of cultural inferiority. Recent furniture scholarship counters these common assumptions by not only demonstrating the unparalleled structural sophistication of much southern furniture but also by revealing the urban British origins of many designs (figs. 19, 20). The essays in American Furniture further this new outlook by exposing the remarkable cultural diversity of the early South.

Still, many questions about southern furniture beg to be answered, even in the analysis of the widespread preference for neat-and-plain forms, which wealthy coastal patrons favored despite having access via transatlantic trade to much more ornate furniture. Southern scholars have documented that this style partly reflected concerns about the stability of intricately carved or veneered furniture in the inhospitable southern climate. To what extent however, was the neat-and-plain style also shaped by the distinctive cultural and demographic character of the coastal South and, in particular, by the hierarchical relationships in both the immediate and extended plantation family? Perhaps the style suitably reflected the material needs and beliefs of a people who were, according to Paulding, “brought up in habits of servility to those above them, and accustomed from their earliest youth to pay a deference to rank, riches, and stations, independently of merit and virtue.” Although Paulding goes on to say that the same residents were not averse to climbing the social ladder aggressively, could the real and imagined plantation landscape have reduced or perhaps redefined how white southerners “kept up with the Joneses”? In comparison to their northern peers, southern planters not only had far fewer neighbors to impress, but also most visitors to their homes generally came from an identical domestic situation.[18]

Might the style, moreover, reflect the region’s decision not to embrace the capitalist-industrial model? As early as 1688, William Fitzhugh of Virginia wrote to his London merchants asking them to send an assortment of silver plate that was “strong & plain, as being less subject to bruise, more serviceable, & less out for the fashion.” Similarly, in 1699, a speaker at the College of William and Mary noted that the education of Virginia children in England taught more about luxury than learning, and countered the “simple and less costly way of living in Virginia.” Could neat-and-plain furniture have functioned as a comfortable, old friend in a world that otherwise was becoming increasingly unfamiliar to the South?[19]

Southern furniture studies also need more thoughtfully to consider the legacy of slavery. If the basic tenet of material culture scholarship is that artifacts are shaped by the specific needs and beliefs of both the makers and users, then we certainly must ask how the material expressions of both planters and slaves were shaped by slavery, which, according to historian Eugene Genovese, is “the foundation upon which the South rose” (fig. 21). Mechal Sobel argues that African-American traditions influenced elite white southern culture in several significant ways. She not only notes the African origins of early southern ideas about time and work, but also attitudes about space, the natural world, spirituality, and the afterlife. Was southern furniture similarly influenced, even in subtle ways, by African Americans, many of whom worked in furnituremaking trades? For evidence we might well look to site-specific examples, including Jefferson’s mountaintop slave community at Monticello. The furniture made there by African-American joiners needs to be evaluated not only in terms of its affinity to European craft traditions brought there by immigrant shopmasters but also in terms of potential ties to African-American customs. In the process, we should consider the specific shop contributions of Jefferson, who closely oversaw the operation and provided many of his own designs. Although professionally connected to elite white culture, Jefferson was raised by and spent much of his private life with African Americans. Equally important evidence survives in the furniture of Thomas Day, a free black artisan in antebellum North Carolina (fig. 22). While unmistakably aware of published urban designs, Day’s work also is distinguished by a highly idiosyncratic and, perhaps, Afro-American-centric decorative vocabulary.[20]

Similar cultural questions surround the complex intermingling of British, Germanic, and Swiss traditions in the southern backcountry (fig. 23). For example, how did German and non-German perceptions about substantial construction inform the design of furniture and houses? Were these material manifestions tied to deeply rooted German ideas about the shaping of strong personal character? Indeed, were Germanic ideas about the proportion and construction of artifacts in any way informed by cultural notions about the preferred shape of the human form, as suggested by early allusions to the “sturdy, four-square German,” to his “jolly portly” wife, and to his children who were described as chubby “rougues with legs shaped like little old fashioned mahogany bannisters”?[21]

Southern material culture scholarship is still in its infancy, and therefore less encumbered by the entrenched interpretive legacy that confronts northern scholars. This freedom from constraint, in turn, facilitates the implementation of innovative analyses of southern history and identity. In his reconsideration of the Puritan origins of American national identity, social historian Jack Greene cites the formative cultural contributions of the early South. Paralleling Greene’s emphasis on American diversity, the essays in this volume of American Furniture counter the culturally monolithic orientation of conventional decorative arts interpretation and question the rules commonly used to measure “quality” and “value.” By doing so, these new perspectives expand our understanding of the American story and, more specifically, the American furniture story.

In the end, the mansions, mockingbirds, and magnolias that characterize the South in American popular history are both real and unreal; so, too, are the region’s sideboards, slab tables, and sugar chests. Thoughtful consideration of not only historical but also mythological evidence will promote a healthy rethinking of American cultural assumptions and a much-needed reevaluation of southern regional identity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author thanks Dr. james Whittinburg, Ronald Hurst, and Luke Beckerdite for their editorial insites and Graham Hood, Betty Leviner, Martha Katz Hyman, Susan Shames, Wallace Gusler, Brock Jobe, and Jessie Poesch for their research assistance. Dr. Katherine Hemple Prowm deserves special recognition for her substantial intellectual and editorial contributions to this essay.

Antiques II, no. 1(January 1927): 27. Jack P. Greene, Pursuits of Happiness: The Social Development of Early Modern British Colonies and the Formation of American Culture (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988), p. 5. Larry J. Griffen, “Why Was the South a Problem to America?” in The South as an American Problem, edited by Larry J. Griffen and Donald H. Doyle (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1995), p. 19. Anne Norton, Alternative Americas: A Reading of Antebellum Political Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), p. 8.

Rachel Raymond, “Construction of Early American Furniture, II. Eighteenth Century Types,” Antiques 2, no. 6 (December 1922): 255–56. Morrison H. Heckscher and Leslie Greene Bowman, American Rococo, 1750–1775: Elegance in Ornament (New York: Harry Abrams for the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1992), pp. 180–81, fig. 123. For more on the context of the master’s chair and its relationship to Masonic symbolism and ritual, see F. Carey Howlett, “Admitted into the Mysteries: The Benjamin Bucktrout Masonic Master’s Chair,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1996), pp. 195–232. Jonathan Fairbanks and Elizabeth Bidwell Bates, American Furniture, 1620 to the Present (New York: Richard Marek Publishers, 1982), pp. 89. Heckscher and Bowman, American Rococo, p. 166.

David L. Smiley, “Quest for a Central Theme,” Atlantic Quarterly 71, no. 3 (summer 1972): 20. Gerster and Cords, eds., Myth and Southern History, pp. 1, xiv. Michael O’Brien, The Idea of the American South, 1920–1941 (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979), p. xi.