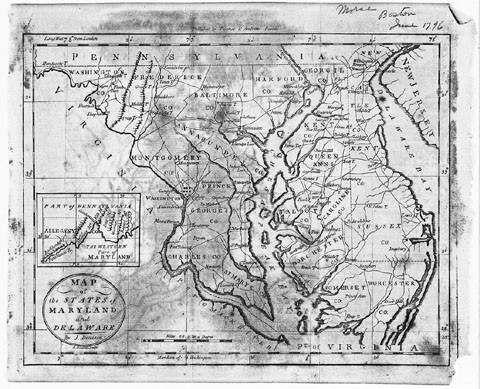

J. Denison, MAP of the STATES of MARYLAND and DELAWARE, published in Jedidiah Morse’s American Geography, 3d ed., 1796, SPECIAL COLLECTIONS (The Huntingfield Map Collection) (Image Format Copyrighted and Courtesy of the Maryland State Archives)

View of Frederick Town attributed to John Markell, 1844. Oil on canvas. 24" x 37 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Chest, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, 1776. White pine and white oak with yellow pine and walnut. H. 23 1/2", W. 44 7/8", D. 22 3/4". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery, Mabel Brady Garvan Collection.)

Chest, probably Frederick County, Maryland, 1770–1780. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 231/4", W. 511/4", D. 23". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, Frederick County, Maryland, 1770–1780. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 29 3/8", W. 56", D. 28 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) The lower portions of the feet are restored.

Schrank, Frederick County, Maryland, 1775–1785. Walnut with tulip poplar. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Maryland Historical Society.) The turned feet are restored.

Chest, Hagerstown, Maryland, 1785. Walnut. H. 24 1/2", W. 31", D. 22 1/2". (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

Desk, Hagerstown, Maryland, 1796. Cherry with yellow pine and cherry. H. 37 5/8", W. 44 1/2", D. 20 3/4". (Courtesy, Washington County Historical Society, Hagerstown; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The desk originally had bracket feet.

Detail of the prospect door of the desk illustrated in fig. 8. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, Frederick County, Maryland, 1780–1790. Walnut; maple and putty inlay. H. 29 1/4", W. 51", D. 24 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 10. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 10. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, Frederick County, Maryland, 1791. Tulip poplar. H. 25 3/4", W. 49", D. 22 7/8". (Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) The feet and base molding are restored.

Conrad Doll, organ case for Peace Church, Hampden Township, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, 1807. Painted softwoods. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Friends of Peace Church and the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall clock with a thirty-hour movement by John Fessler, Sr., Frederick Town, Maryland, ca. 1785. Painted softwoods. H. 84 1/2", W. 20 3/4", D. 10 7/8". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Tall clock with an eight-day movement by George Schnertzel, Frederick Town, Maryland, ca. 1780. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 104", W. 19 1/2", D. 11 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The base is restored.

Detail of the frieze of the tall clock illustrated in fig. 16. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall clock with a thirty-hour movement by George Woltz, Hagerstown, Maryland, 1789. Walnut. Secondary woods and dimensions not recorded. (Illustrated in Pauline Pinkney, “George Woltz, Maryland Cabinetmaker," Antiques 35, no. 3 [March 1939]: 125.)

Tall clock with a thirty-hour movement by Jacob Young, Hagerstown, Maryland, ca. 1785. Walnut. Secondary woods and dimensions not recorded. The feet and rosettes are restored. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the hood of the tall clock illustrated in fig. 19. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall clock with a thirty-hour movement signed “John Myer, Frederick Town,” Maryland, 1770–1790. Cherry with tulip poplar. H. 97 5/8", W. 20 1/8", D. 10 5/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Detail of the waist door of the tall clock illustrated in fig. 21

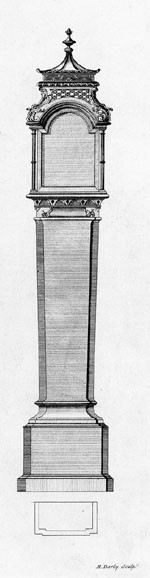

Design for a tall clock illustrated on pl. 163 in the third edition of Thomas Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1762). (Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Tall clock with an eight-day movement signed “Elijah Evans Frederick Town,” Maryland, 1780–1789. Cherry with tulip poplar. H. 98 1/4", W. 21 1/2", D. 11 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Tall clock with an eight-day movement signed and dated “Thos. Liddell Frederik Town 1760,” Maryland. Walnut with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 102 3/8", W. 20 1/4", D. 10 1/2". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Frederick County, Maryland; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the waist door of the tall clock illustrated in fig. 25. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Desk-and-bookcase, Frederick Town, Maryland, 1780–1800. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 96 1/2", W. 45", D. 21 7/8". (Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) The bookcase section has been shortened.

Detail of the prospect of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 27.

Desk-and-bookcase, Frederick Town, Maryland, 1780–1800. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 94", W. 42 1/2", D. 23 1/2". (Courtesy, Carlyle House Historic Park, owned by the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall clock, Frederick Town, Maryland, 1780–1800. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 104 1/4", W. 21 1/4", D. 11 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail of the hood of the tall clock illustrated in fig. 30.

Tall clock with an eight-day movement signed “John Fessler,” Frederick Town, Maryland, 1780-1810. Cherry with tulip poplar. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Baltimore Museum of Art.)

Detail of the hood of the tall clock illustrated in fig. 32.

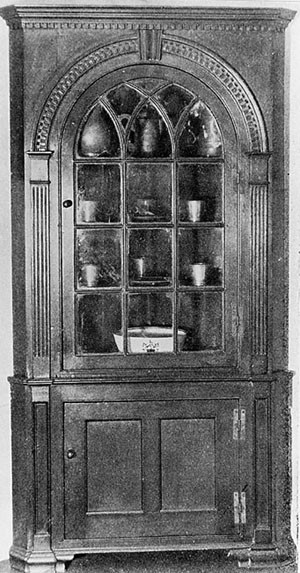

Corner cupboard, Frederick County, Maryland, 1780–1800. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 91". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Frederick County, Maryland; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet are old replacements.

Detail of the carving on the corner cupboard illustrated in fig. 34. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Corner cupboard, Frederick County, Maryland, 1780–1800. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 89 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) The flame sections of the finials are missing.

Detail of the carved fan and mullions on the door of the corner cupboard illustrated in fig. 36.

Corner cupboard, Frederick County, Maryland, 1780–1800. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Illustrated in Wallace Nutting, Furniture Treasury [New York: MacMillian Co., 1928], fig. 534.)

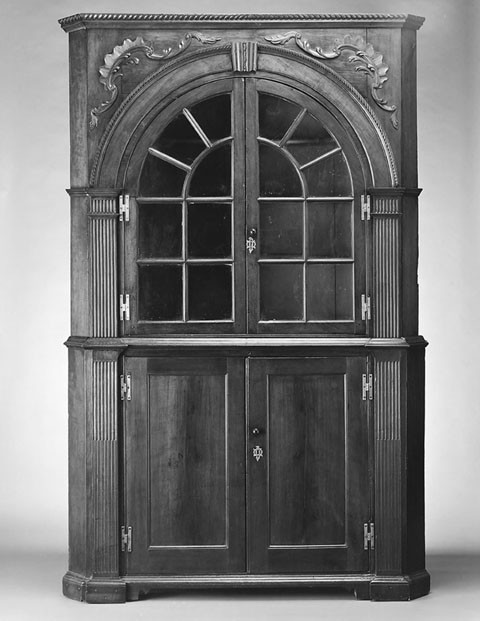

Corner cupboard, Frederick or Washington County, Maryland, 1790–1810. Tulip poplar. H. 100", W. 48 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Chest of drawers, Frederick County, Maryland, or Washington County, Virginia, 1780–1800. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 77 7/8", W. 39 1/4", D. 23 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Greg Vaughan.) The feet and base molding are replaced.

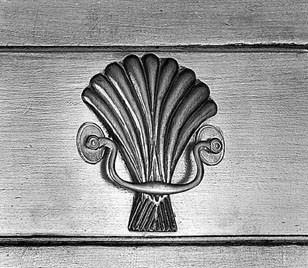

Detail of the shell appliqué and cornice molding on the chest illustrated in fig. 40.

Tall clock, Frederick Town, Maryland, 1785–1800. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 106", W. 23", D. 11 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the hood of the tall clock illustrated in fig. 42. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall clock with an eight-day movement signed “John Fessler,” Frederick Town, Maryland, 1785–1800. Walnut with tulip poplar and white pine. H. 103 1/2", W. 23", D. 11 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Tall clock with an eight-day movement signed “Valentine Steckell,” Frederick Town, Maryland, 1790–1810. Walnut with tulip poplar. Dimensions not recorded. The feet and base molding are restored. (Courtesy, Historical Society of Frederick County, Maryland; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the hood of the tall clock illustrated in fig. 45. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Corner cupboard, Frederick County, Maryland, 1780–1800. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 89 1/2", W. 50 1/2", D. 32 1/4". (Courtesy, Sumpter Priddy III, Inc.) The upper case has been shortened.

Detail of one of the tympanum appliqués of the corner cupboard illustrated in fig. 47.

Corner cupboard, Frederick County, Maryland, 1780–1800. Yellow pine; polychrome paint. H. 96", W. 56 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the entablature and cornice of the corner cupboard illustrated in fig. 49. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Windsor chair, Frederick County, Maryland, ca. 1810. Maple and tulip poplar; painted. H. 33 1/2", W. 21 1/4", D. 16". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the crest rail of the Windsor chair illustrated in fig. 51. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The chip carving on the crest rail has flowers that turn outward like the relief carving on a group of Frederick County cupboards.

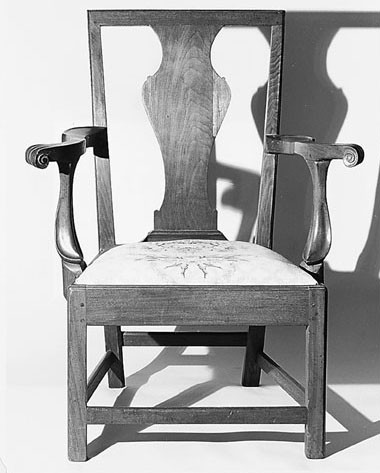

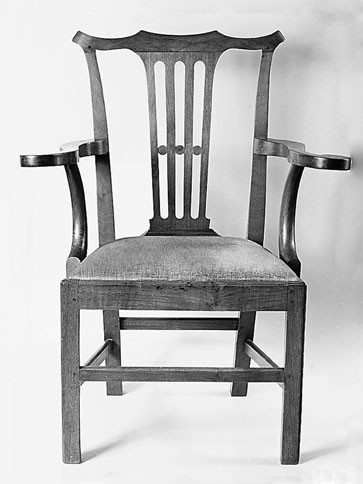

Armchair, Frederick County, Maryland, 1770–1790. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 39 1/8", W. 22 3/8" (seat). (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) This chair descended in the Tyler family of “The Shelter,” in Prince William County, Virginia.

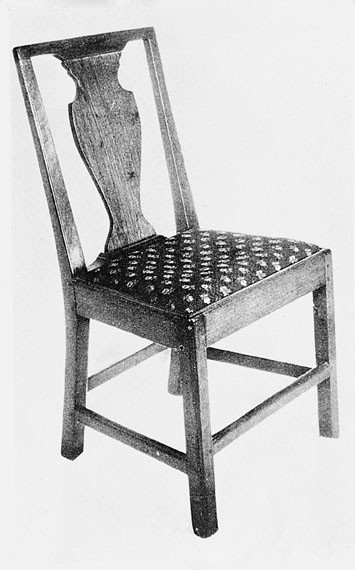

Side chair, probably Hagerstown, Maryland, 1770–1790. Walnut. Secondary woods and dimensions not recorded. (Illustrated in Pauline Pinkney, “George Woltz, Maryland Cabinetmaker,” Antiques 35, no. 3 [March 1939]: 124–27.)

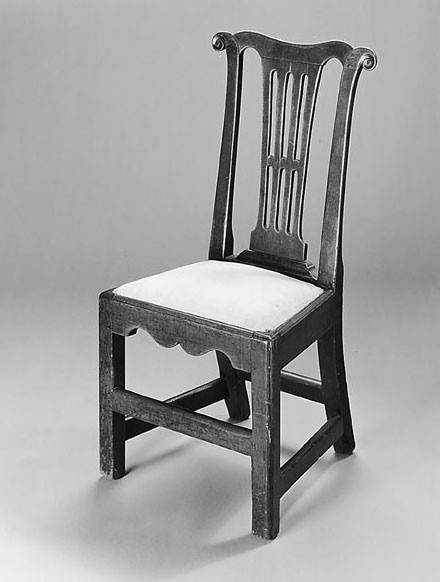

Side chair, Frederick Town, Maryland, 1770–1790. Walnut. H. 40 1/2", W. 22 1/4", D. 19". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Armchair, Frederick Town, Maryland, 1770–1790. Walnut with white pine. H. 37 1/4", W. 21 7/8" (seat). (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Side chair, Frederick County, Maryland, 1770–1800. Walnut. H. 37 1/2", W. 18 5/8", D. 14 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Sumpter Priddy, Inc.)

Side chair, Frederick Town, Maryland, 1780–1800. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 39 1/2", W. 17 1/4" (seat). (Courtesy, All Saints Parish; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Corner cupboard, Frederick County, Maryland, 1780–1800. Cherry with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 107", W. 47 1/2". (Courtesy, Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village.)

Detail of the pediment of the corner cupbard illustrated in fig.59.

The mechanics are numerous, in proportion to the aggregate; and the Spirit of Industry seems to pervade the place.

—George Washington, August 7, 1785

The boundaries of western Maryland have never been clearly defined. To many, this geographic designation suggests the lands beyond the Blue Ridge Mountains, but historically “western Maryland” encompassed the entire territory beyond the “fall line”—where ships could continue no further upriver, where rolling hills and gentle mountains emerged from the landscape, and where people, goods, and ideas moved over land (fig. 1). Like other inland regions where geography inhibited access, this area of Maryland was referred to in eighteenth-century parlance as the “backcountry,” “backlands,” and “backwoods.”[1]

Maryland’s backcountry was sparsely populated during the early eighteenth century. As early as 1732, Governor Charles Calvert attempted to attract colonists to the region by offering land on favorable terms. Like other colonial officials, he hoped that these settlers would secure raw materials for British manufacturers, constitute a new market for British goods, and provide a buffer against French forces on the western frontier. After a 1748 Act of Assembly established the boundaries of Frederick County (which encompassed Frederick, Washington, Allegheny, Garrett, Montgomery, and portions of Carroll and Howard Counties today) and made Frederick Town the county seat (fig. 2), the region’s population grew dramatically as large numbers of settlers arrived from eastern Maryland, southern Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Europe.[2]

Because of its growing population, Frederick County was partitioned in 1776, with the formation of Washington and Montgomery Counties, and in 1787, with the formation of Allegheny County. In 1790, Frederick County had 30,971 inhabitants, Washington County had 15,822, Montgomery County had 18,003, and Allegheny County had 4,809. In 1791, Frederick County had four hundred stills, eighty grist mills, two glass houses, two iron furnaces, two forges, and two paper mills. Agriculture was the foundation of the region’s economy, and Frederick County led the state in grain production. In 1813, William Harris Crawford (1772–1834) observed that “the crops of wheat and other grains from Monocacy river to Frederick Town to Woodville . . . [were] superior to any thing I had ever seen.” These agricultural and manufacturing industries created a strong economic base in western Maryland. With prosperity came a demand for furnishings that surpassed those produced in most rural communities.[3]

During the eighteenth century, western Maryland had two principal trading centers—Frederick Town and Hagerstown. Frederick Town was founded by Irish immigrant Daniel Dulany (1685–1753) in 1745. Although Dulany lived and practiced law in Annapolis, he acquired a vast tract of land in “the backwoods” as a speculative investment. He described this region as a “delightful Country . . . that Equals . . . any in America . . . well furnished with timber of all sorts, abounding with . . . stone fit for building . . . and to Crown all, very healthy.” After dividing Frederick Town into 351 lots, Dulany sold most of the property to freeholders of Germanic and British descent. Many of the town’s earliest residents were tradesmen, including seven cabinetmakers and two joiners. In 1771, Annapolis customs inspector William Eddis wrote, “from an humble beginning, has Frederick Town arisen to its present flourishing state. . . . Provisions are cheap, plentiful, and excellent. . . . [H]ere are to be found all conveniences, and many superfluities.”[4]

Hagerstown was founded by Jonathan Hager, a German immigrant who arrived in Philadelphia in 1736. He purchased two hundred acres of land from Daniel Dulany in 1739 and, after acquiring additional tracts, founded Elizabeth Town (named after Hager’s wife) in 1762. Elizabeth Town was renamed “Hagerstown” and made the seat of Washington County at the beginning of the Revolution. Because of its location and date of settlement, Hagerstown grew more slowly than Frederick Town. In 1771, William Eddis noted that Hagerstown had “more than a hundred comfortable edifices” and that it was “making quick advances to perfection.” He also believed that Hager’s “encouragement to traders” was critical to the town’s success.[5]

Although Frederick Town and Hagerstown were in the heart of Maryland’s backcountry, they were not isolated. Western Maryland was criss-crossed by old roads built on ancient Indian trails and new roads chartered by the colony and state. The “Old Indian Trail,” or Monocacy Road, led from Frederick Town into south central Pennsylvania, and the “Great Wagon Road” ran from Pennsylvania through Hagerstown, Martinsburg and Winchester, Virginia, and down the Shenandoah Valley four hundred miles into Tennessee. Travelers from eastern Maryland came by two separate routes—one from Baltimore and one from Annapolis—that converged in Frederick Town then continued over the mountains to Hagerstown, Pittsburgh, and the Ohio territory. From eastern Virginia, settlers followed the trails that led from Fredericksburg to the headwaters of the Rappahannock, then across the piedmont to Winchester. Others came by the “River Road” that ran near the Potomac from Alexandria and Georgetown. Frederick Town and Hagerstown were often a final destination for many of the artisans who traveled these roads, but others stayed only a brief time. The furniture produced in both towns reflects this constant influx of new tradesmen and patrons.[6]

The culture and economy of western Maryland were linked to Pennsylvania, eastern Maryland, and northern Virginia. Chambersburg, Carlisle, and Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, were important commercial centers within fifty miles of Frederick Town. Although slightly more distant, York and Lancaster were points of departure for many of the Germanic settlers who moved from Pennsylvania to western Maryland. Along the Potomac River in (West) Virginia were Harper’s Ferry and Shepherdstown, and slightly further inland were Charlestown and Martinsburg. Nestled in the rolling hills of Virginia’s northern piedmont were Winchester, Berryville, Middleburg, and Leesburg. In western Maryland, Sharpsburg, Margaretsville (Boonsboro), Cumberland, Emmitsburg, Liberty Town, Taney Town, and New Market emerged as small but important economic centers. Artisans moved freely within this larger region, living at one time in Maryland, at another in Virginia, at another in Pennsylvania. Over 150 cabinetmakers and joiners worked in western Maryland before 1820.[7]

Most of the Germanic settlers in western Maryland were from Protestant families who came to the colonies to escape religious persecution in the Palatinate during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The earliest emigrés arrived in Philadelphia. Although some remained in the city, most traveled westward, settling in the countryside or in one of the inland towns like Lancaster or York. From the outset, the colony’s Germanic community was culturally diverse. In addition to refugees from the German states, a large number of Mennonites from the valley of the upper Rhine and Switzerland emigrated to Pennsylvania.[8]

As the population of southeastern and western Pennsylvania grew and land became more expensive, many of these Germanic people moved south, settling in western Maryland, the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, the Carolina backcountry, and Tennessee. To encourage settlement in western Maryland, Lord Baltimore offered colonists two-hundred-acre tracts of inexpensive land “in fee simple.” Although most of the Germanic settlers in Maryland came from Pennsylvania, evidence suggests that over a thousand Teutonic immigrants arrived in Annapolis during the first half of the 1750s and countless others followed. Later in the century, Baltimore became an important port of entry for European immigrants. John Frederick Amelung, who established the New Bremen “Glassmanufactory” in Frederick County, arrived in Baltimore on August 31, 1784. Fifteen of his workers arrived there later in that year. The influx of Germanic artisans continued through the end of the eighteenth century. On October 6, 1792, the ship Waaksaamheyd arrived with “German redemptioners,” including glassmakers, potters, stonecutters, whitesmiths, carpenters, cabinetmakers, and “a single Man of approved Abilities in making of Varnishes, Gilding, Carving, ornamental stone cutting and coach painting.” William Eddis attributed the “advancement of settlements” in western Maryland to “the arrival of many emigrants from the palatinate, and other Germanic States [who] . . . had been disciplined in the habits of industry, sobriety, frugality, and patience” and who were responsible for creating “the first improvements.”[9]

The fact that Teutonic immigrants arrived in many American ports complicates the study of Germanic furniture in America. Cultural expressions are rarely respectful of political boundaries, and many objects traditionally attributed to Germanic artisans in Pennsylvania were actually produced in other colonies. To further illustrate the point, some artisans who lived in Pennsylvania came to western Maryland for training. On December 29, 1761, Mathias Baker, Sr., of York County, Pennsylvania, bound his son Mathias to Godfrey Brown of Frederick County, Maryland, “to learn the trade of a Joyner.”A group of Germanic chests from Pennsylvania and Maryland share a common cultural background. The chest illustrated in figure 3 has elaborately decorated panels, the center of which is initialed “•C•B••H•B•,” and an interior inscription identifying its original owner, Casper Hildebrand of Lancaster. Like other chests produced by immigrant Palatinate artisans, it has details that resemble those on Continental German examples made from the late seventeenth through the late eighteenth centuries. Dozens of closely related chests, constructed of painted softwoods or of walnut, were made in Pennsylvania—particularly around Lancaster County.[10]

A similar chest associated with “White Oak Forest Farm,” near Hagerstown, represents either Pennsylvania or Maryland production (fig. 4). This piece may have descended in the Beachtel family, who purchased the property in 1738, or in the family of Joseph Loose, who was born in Pennsylvania in 1810 and married Henrietta Beachtel in 1844. The iron handles on the ends of the case, the profiles of the lid and base moldings, and the design of the facade vary little from the Pennsylvania example shown in figure 3. Subtle differences can be found in the dentil course added to the base molding, in the slightly smaller feet, and in the pilaster flutes, which abut the capitals rather than terminate below them.[11]

A slightly later chest that descended in the Beachtel family (fig. 5) was undoubtedly made in the Hagerstown area; however, it clearly emanates from the same cultural tradition, if not shop tradition, as the preceding example (fig. 4). The joiner substituted five ogee feet for the turned feet on the earlier example and added two lipped drawers. The medial and base moldings on the later chest are interrupted at their junctures with the drawer divider, feet, and plinths of the outer pilasters. One of the most intriguing design elements on this chest is the scalloped appliqué above the drawer divider, which presages the carved ornament on a later western Maryland chest (fig. 7). The joiner’s use of ribbon-figured walnut is also associated with furniture made in the vicinity of Hagerstown and Frederick Town. The fluted pilasters on the facade are a more generic detail. Chests from Pennsylvania, western Maryland, and the Valley of Virginia occasionally have this feature.

Chests or kistch were the most common storage forms in Germanic households. Young women of Germanic descent typically received chests as gifts for dower goods before their marriage. This tradition was such an integral part of German culture that even female servants often received chests when their indentures expired. On February 25, 1805, Tille Dorff was bound to John Martin of Frederick County. In exchange for performing “all kinds of House and out of Door work,” she was to receive a “Common Chest without Drawers,” a bedstead, two “common Stools,” a blanket, a bed quilt, a new spinning wheel, and “a new suit of cloaths, such [as] is common for farmers.”[12]

Schranken were also traditional storage forms, and like chests, they had important cultural connotations as symbols of cleanliness, prosperity, continuity, and order. A schrank found in Libertytown (fig. 6) is roughly contemporary with the Beachtel family chests. All three pieces have fluted pilasters and moldings that are secured with large, diamond-shaped pins. Intentionally exposed structural details, such as these pins and the dovetails on the frieze of the schrank, are typical of Germanic work. Like the schrank, many corner cupboards from western Maryland have pilasters flanking the doors.[13]

A chest and desk with their production dates and owners’ initials inlaid in white putty (probably white lead, calcium carbonate, or sulfur) show how Frederick County furniture styles evolved during the 1780s. The chest is initialed “HS” and dated “•17•85” (fig. 7). Like the chests that descended in the Hildebrand and Beachtel families (figs. 3, 4, 5), this example has a dovetailed case underlying an architectural facade. Its straight bracket feet are made from the same piece of wood as the ovolo-and-ogee base molding. These molding/foot components are mitered at the corners, pinned to the bottom board of the case (without overlapping the front or sides), and reinforced at each corner with large, wrought-nailed blocks that extend diagonally toward the center of the chest. Like the ogee-foot chest from the Beachtel family (fig. 5), the “HS” example has an astragal molding that separates the drawers from the chest section and forms capitals for the fluted plinths below. The carved fans above the plinths are one of the most distinctive features of this chest. Although fan ornaments are relatively common in neoclassic architecture, they are seldom encountered on furniture. In western Maryland, however, they occasionally occur on joiners’ work, particularly on the doors of neoclassical corner cupboards.[14]

The drawers of the “HS” chest (fig. 7) have several features found on other pieces from the region. The drawer fronts have ovolo lip moldings that overlap the case on all four sides like those on the ogee-foot chest from the Beachtel family (fig. 5). Also typical of Frederick County work, the drawer frames of the “HS” chest have three large dovetails at each corner. The dovetails at the front are conventional, but the ones at the back are reverse-pinned—a relatively common Germanic detail shared by another chest from the same shop. The drawers of the “HS” chest run on their bottoms, which are nailed into an open rabbet in the front and directly to the bottom of the sides and the back.[15]

A desk made in the same shop has an elaborately shaped prospect door dated “1796” and initialed “M•R•” for Martin Rohrer of Hagerstown (figs. 8, 9). Rohrer’s father, Jacob, purchased Jonathan Hager’s stone house in 1745 and subsequently raised his family there. Although the desk has lost its original feet, the inlaid numerals and drawer construction of the desk are virtually identical to those on the “HS” chest (fig. 7). The curvilinear design of the inlay on the prospect door resembles the applied panels on the plinths of several Frederick County tall case clocks.[16]

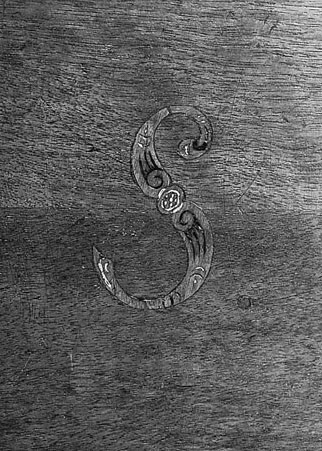

Western Maryland artisans used both putty compounds and contrasting woods for inlay. The chest illustrated in figure 10 has elaborate script initials inlaid in maple or another light-colored hardwood. The letters “DS” refer to the original owner, Daniel Sayler (1775–1850) of Beaver Creek in Frederick County (figs. 11, 12). The inlay maker used gouges and a V-shaped parting tool to define and shade the letters, then he filled the cuts with a putty similar to that used on the preceding chest and desk (figs. 7, 8). Not only do the carving techniques resemble those used by regional gunmakers, but the practice of inletting colored fillers has antecedents in European arms and armor. Although elaborate script letters occasionally appear on Pennsylvania furniture, they do not usually exhibit this degree of detail.[17]

The painted decoration on the chest illustrated in figure 13 is also unusual from a technical standpoint. As its inscription suggests, it was made in 1791 for Adam Neff of Frederick County. Colorful and expressive, this simple dovetailed case has sgraffito decoration: the design was incised through a coat of damp green paint to reveal the brilliant orange color beneath. Although sgraffito-decorated earthenware was prized by the Palatinate Germans and was relatively common in Europe and Pennsylvania, only a few pieces of furniture have figural decoration in this technique alone. Variations of this vase-and-flower design appear on other furniture from western Maryland.[18]

Further insight into the work of Germanic artisans in western Maryland is provided by the ledger of Frederick Town joiner Joseph Doll (1747–1819). His parents, Johannes and Catharina (Hartmann), emigrated to Pennsylvania in 1741 from Bretten, in the Palatinate. By 1747, they had settled in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Their son Joseph was baptized in the First Reformed Church in Lancaster in May of that year. Johannes Doll’s trade is not specified in any record, but circumstantial evidence suggests that he may have been a joiner. His oldest son, Johannes (b. 1736), was schoolmaster at Lancaster’s First Reformed Church, but his next two sons worked in the woodworking trades. Conrad (b. 1739) was a cabinetmaker, and Joseph was a house joiner who occasionally made furniture. The younger Johannes’s son Conrad (1772–1819) was also a joiner and cabinetmaker, and he is the only member of the family for whom documented work is known. A highly carved organ case that the younger Conrad designed and constructed for Peace Church in Hampden Township, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, still survives in its original location (fig. 14). Its paneled pilasters, carved rococo C scrolls, and pitch pediment have much in common with early cabinetmaking in western Maryland.[19]

Like many Germanic families that settled in Pennsylvania during the eighteenth century, the second generation of the Doll family headed west and then south. Johannes’s sons Joseph and Conrad both moved to Maryland in the 1760s. Conrad arrived by 1761, when he married Anna Maria Schisler in the Evangelical and Reformed Church in Frederick Town. Joseph joined his brother later in the decade, probably after the death of their father on February 3, 1765. He married Charlotte Storm in Frederick Town and helped raise a family of fourteen children.[20]

Joseph Doll’s ledger (written in phonetic English) indicates that he provided a wide range of products and services for his Germanic and British neighbors between 1761 and 1789. The largest portion of his business involved the production of an astonishing variety of building materials, including sills, joists, flooring, studs, lath, rafters, and shingles. Except for an occasional door or window sash, Joseph Doll was not involved with finish carpentry or interior woodwork. Similarly, furniture making was only a small part of his business. His ledger indicates that he constructed less than twenty pieces between 1773 and 1777 and a few scattered examples in the following years.[21]

Doll produced more bedsteads than any other form: Six had low posts, one had high posts, and two were cradles. The low-post bedsteads ranged in price from eleven shillings to twelve shillings eight pence. Four were made in pairs, one of which was “Painted Green.” The “bedStid with high Posts painted blue with four Scroos” was the only example assembled with bed bolts. Made in 1787, it cost £2.7.6—over twice as much as any bedstead from the prior decade. The second most expensive bedstead was purchased by Christian Weaver. In 1774, he paid £1 for a “Greadle to Rog his Chylde.” The other cradle, made the following year, cost John Brunner 18 shillings.[22]

Doll’s ledger also records the production of seven tables that ranged in price from £1 to £1.8. Although two of the tables were not described, two were “walnut,” one had “2 Drawers and brass hands,” one was referred to as a “Kitchin Table,” and one was described as a “Larch Pobler Table for a workebench with Two Trawers in it with divicions.” John Hoober, a glass engraver at Amelung’s New Bremen Glassmanufactory, paid Doll £1.7 for the latter in 1775. [23]

Doll produced only four case pieces, but they were the most expensive furniture forms recorded in his ledger. John Brunner paid £3.15 for a “Kitchin Cobert” in 1775; Casper Mantz paid £3.5 for a “Chest with drawers” for his “Daughter Caety” in 1775; Peeter Brunner paid £7 for a “Kitchen Dresser with glas and furniture” in 1776; and John Kyle paid £4.10 for a “Corner Cobbert” in 1789. The dresser Doll made for his neighbor Brunner was twice as expensive as any piece he had made prior to that time, and over two and a half pounds more than any recorded later in his career.[24]

Like many other woodworkers, Doll made coffins. Between 1775 and 1789 he made seven at prices ranging from five shillings to £1.15. He also repaired furniture and made a variety of kitchen goods, including a door for a fireplace, a cutting box, and a bread tray with a lead liner. His ledger indicates that he mended several chairs and made Henry Cronier “a Sidepeese to his bedStid paint blue.” Regrettably, none of the surviving household furnishings from western Maryland can be associated with Doll’s ledger entries.[25]

Although the products of most of the Germanic artisans who moved from Pennsylvania to western Maryland remain anonymous, a large group of tall case clocks made by Germanic clockmakers and cabinetmakers in Frederick County survives. These cases range from simple, flat-top examples to carved ones with elaborate scrolled pediments. The simpler end of the spectrum is represented by a case with a thirty-hour, brass dial movement by John Fessler, Sr. (1760–1820), one of the most productive clockmakers in Frederick Town (fig. 15). His parents were Swiss immigrants who arrived in Pennsylvania in 1760 and subsequently settled in Lancaster. Fessler served in the Continental Army from 1777 to 1782, and, like many of his contemporaries from Europe, he moved to western Maryland after the Revolution.[26]

The case for Fessler’s clock has a flat hood with a broad cove cornice, a plain frieze, a square door conforming to the brass dial, a rectangular waist door with Germanic “rat-tail” hinges, and a paneled plinth with an ogee base molding. The front of the case that surrounds the waist door consists of a mortise-and-tenon frame that is pinned to the case sides. Like the simplest chests from the region, such cases are derived almost verbatim from their European counterparts. Numerous flat-top cases with thirty-hour, or “long-day,” movements were made in western Maryland, but most have imported British hinges, thinner stock, and other concessions to Anglo-American style.

One of the most expensive Germanic cases from western Maryland (fig. 16) has an eight-day movement by George Schnertzel of Frederick Town (fl. 1772–1810). This clock case is the only example from the region with a leaf-carved, pulvinated frieze (fig. 17)—a feature that appears on a few Philadelphia clock cases made during the 1760s and 1770s. The pediment scrolls on the Schnertzel clock are unusually low, as are those on several similar cases with movements by Eli Bentley of Taney Town, Maryland, and Arthur Johnson and George Woltz of Hagerstown.[27]

The tall case clock illustrated in figure 18 has a thirty-hour movement signed “George Woltz Hagers Town” and dated “1789.” Woltz’s parents were Swiss immigrants who settled in York, Pennsylvania, by 1731. Woltz (1744–1812) purchased a lot in Hagerstown in 1774 and served as a major in the Maryland Militia in Annapolis in 1776. After the Revolution, he returned to Hagerstown, where he worked until his death in 1813. The earliest documented clock by Woltz descended in his family.[28]

Although local tradition maintains that Woltz made clock cases and other household furniture, there is no documentary evidence that he was a cabinetmaker. The cherry and walnut furniture listed in his probate inventory and cited by one scholar as evidence of his woodworking skills was nothing more than the personal possessions of a prosperous artisan. He did not own any chisels, molding planes, or other specialized tools necessary for the production of case furniture. His inventory listed only clockmaking tools and an “unfinished” movement.[29]

Movements by Woltz and his competitors are often housed in cases from the same cabinet shops. The clock case illustrated in figures 19 and 20 has a thirty-hour movement by Jacob Young, who worked in Hagerstown from the late 1770s until his death in 1792; however, the case is clearly by the same hand that made the one for the signed Woltz movement (fig. 18). A less expensive but related case has a thirty-hour movement by Hagerstown clockmaker John Itnyer (d. 1786).[30]

Most of the early Hagerstown cases with movements by Woltz and his competitors have bold ogee feet, a scalloped panel applied on the plinth, fluted quarter-columns, a waist door with an arched head with ogee-shaped shoulders, an astragal molding below the frieze, and broad cove moldings above. The principal differences between the cases for the Woltz and Young clocks occur on their hoods. The hood on the Woltz clock has simple baluster colonettes and a flat top, whereas the one on the Young example has fluted colonettes and a broken-scroll pediment. The scrolled pediment has an unusually deep tympanum and a decidedly vertical thrust—features that occur on closely related cases with movements by several other Hagerstown clockmakers. On the Young case, the shell-shaped keystone and molded, tulip-shaped plinth for the central finial signify the work of an accomplished joiner. Several clock cases and related desk-and-bookcases with similar pediments were made in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, during the last three decades of the eighteenth century. The Woltz and Young cases may represent the work of a joiner who trained or worked as a journeyman there.[31]

Although none of these cases are signed, several Hagerstown cabinetmakers were capable of producing them. William Conrad, who was described as a “joiner,” purchased a town lot in 1775. His 1790 inventory lists one of the most complete sets of molding planes recorded in the region and “2 Books called Swans Architecture” valued at £6.5. More importantly, the cabinetwork in his shop included “2 falling unfinished Tables” and “1 Cherry Clock Case” that, together with “a piece of iron,” were valued at £9.4.6. The wide variety of clock cases and movements made in the Hagerstown area suggests that a high degree of craft specialization existed there by the end of the Revolutionary era.[32]

Throughout western Maryland, joiners who had trained in vernacular traditions worked in close proximity to cabinetmakers, chairmakers, and other tradesmen with urban backgrounds. In contrast to the Germanic work discussed at the beginning of this article, other Frederick County furniture reflects the influence of British design and construction techniques. Much of this furniture, however, may have been produced by tradesmen working outside the English mainstream, including artisans of Scottish and Irish descent and Germanic tradesmen working in a British style.

Although a large number of artisans from different cultures worked in western Maryland, much of their work can be separated into individual shop groups. Structural and stylistic details shared by these groups also indicate that a distinctive regional taste emerged during the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Many of the surviving pieces have strong family provenances or other histories that place them within the boundaries of old Frederick County. These objects provide a solid foundation for understanding how the convergence of artisans and cultures influenced furniture styles and trade practices within the region.

Two tall clock cases—one with a thirty-hour movement by John Myer (figs. 21, 22) and the other with an eight-day movement by Elijah Evans (fig. 24)—introduce this diverse group of early Frederick County furniture. Despite the outward differences of their pediments and bracket feet, these cases evidently represent the work of a single artisan or shop. Both cases have unfluted quarter-columns, and their moldings, keystones, Doric colonettes, and waist doors are virtually identical. All of these details were clearly inspired by British tall clocks of the 1760–1790 period.

The pagoda-shaped pediment of the Myer clock (fig. 21) suggests that the case maker had access to British design books or, at the very least, that he had an acute awareness of rococo furniture and architectural styles. Similar pediments appear on a clock case with a movement by Robert Grieff of Beath, Scotland; a clock case illustrated on plate 163 in the third edition of Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1762) (fig. 23); a “china case” shown on plate 49 in the Society of Upholsterers’s Houshold Furniture in Genteel Taste (1760); and a variety of buildings and interior details illustrated in English architectural design books, such as Sir William Chambers’s Designs of Chinese Buildings, Furniture, Dresses, Machines, and Utensils (1757) and William Paine’s Builder’s Companion and Workman’s General Assistant (1758).[33]

The waist door of the Myer case is capped with a small carved shell and flanking acanthus leaves (fig. 22). The cabinetmaker used a gouge to hollow out the lobes of the leaves rather than flute and shade them in a conventional manner. His techniques produced a stylized design that contrasts with the naturalistic carving from most urban centers and larger towns on the periphery of western Maryland, such as York, Lancaster, and Reading. Several other pieces of Frederick County furniture have carving that is conceived and executed in a similar manner, possibly owing to the lack of professional carvers there.[34]

Although British influences are apparent in the design of the Myer and Evans cases, the small carved tulip below the center finial on the Evans clock (fig. 24) and the wedged dovetails and thick stock of both pieces are Germanic stylistic and structural conventions. History suggests that understanding these overlays of culture is more complex than identifying the origins of individual details. North German styles were introduced into England with the crowning of George I and the subsequent influx of Hanoverians into Britain. Conversely, Germanic artisans returning home carried British details with them.

A clock case with a movement inscribed “Thos. Liddell Frederik Town 1760” is from a different cabinet shop (fig. 25), but it shares several important features with the Evans and Myer examples. It has a waist door with a small shell like the Myer clock (fig. 21) and ogee feet with spurlike cusps, a high arched pediment, and a tympanum similar to those on the Evans example (fig. 24). On the Liddell case, however, the side moldings of the cornice return partially around the front and function as imposts for the scroll moldings above. Below each cornice return is a fluted block intended to represent a pilaster. Similar blocks appear on the pediments of other case pieces from the region as well as on numerous Pennsylvania examples. High arched pediments and tympana with tight, semicircular cutouts like those on the Liddell and Evans clocks are common on other furniture from the Frederick Town area. These profiles also have numerous parallels in case furniture from Pennsylvania; however, it is unclear whether the designs came from England, the Continent, or the Middle Atlantic region.

The Liddell case has several other details that appear repeatedly on furniture from western Maryland. The overlapping-diamond fretwork on the frieze (fig. 26) is repeated in various forms on at least a half-dozen case pieces made in the vicinity of Frederick Town during the last quarter of the eighteenth century. The incurved ogee feet on the Liddell clock, which are the earliest and most pronounced of their form, are probably based on British prototypes. Incurved ogee feet occur on furniture from southeastern Pennsylvania, the Tidewater region of Virginia, northeastern North Carolina, New York, and Connecticut. They are, however, unusual in Frederick County, where straight bracket feet or conventional ogee feet were the norm.

As the preceding clock cases suggest, the convergence of tradesmen and patrons from different cultures resulted in the production of distinctive and surprisingly creative furniture forms in western Maryland. This diversity is further illustrated by a group of desk-and-bookcases, clock cases, and corner cupboards made in or near Frederick Town during the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Collectively, these objects reveal a great deal about the cabinetmaking trade in the town and the evolution of furniture styles within the region.

Frederick Town cabinetmakers made desk-and-bookcases with complex interiors prior to the Revolutionary War. In 1770, Henry Wilson sold his neighbor John Fillson “one Black Walnut Desk carved work in the Inside with a prospect door.” The desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 27 has a history of ownership by Barbara Fritchie, a nineteenth-century resident of Frederick Town. It has a writing compartment with concave-blocked drawer fronts, elaborately shaped pigeonhole dividers, and a prospect door flanked by pilasters and surmounted by a dentiled architrave (figs. 27, 28). Both the pilasters and architrave pull out to reveal document drawers, and the entire prospect section conceals ten secret drawers. The spandrels, keystone, moldings, and facade of the prospect door are carved from the solid. The shells and leaves resemble those on the doors of the Myer and the Liddell clocks (figs. 22, 26), and the fluted pilasters and dentils of the architrave have parallels in early dower chests and clock cases from the region (see figs. 4–7, 25). The cases are constructed using full-depth dustboards that are thinner than the drawer rails. Like the “HS” chest (fig. 7) and the Rohrer desk (fig. 8), the bottoms of the large drawers of the desk-and-bookcase are nailed from beneath to the lower edges of the drawer sides, but here, small strips are attached to the bottoms to serve as runners.[35]

The desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 29 has doors with highly figured walnut panels and circular carved fans. No other furniture from western Maryland or the Middle Atlantic region has fans that are comparable in size or placement. Small carved fans were popular furniture ornaments in both regions, but they were usually limited to the valances of pigeonholes, small interior or exterior drawers, and prospect doors. Quarter-fans and half-fans were the most common varieties, but examples carved in the round were occasionally employed.

Although different in form, the pediments of these desk-and-bookcases are related in having both a frieze and cornice below their scroll pediments. The pediment of the fan-carved example is similar in shape to those on a number of Frederick Town case pieces derived from German prototypes, as exemplified by the Schnertzel clock case (fig. 16). The pediment on the Fritchie desk-and-bookcase (fig. 27) has higher scrolls, a tympanum with broad, elliptical openings, and a fluted, half-round plinth for the central finial. Variations of these last details also occur on an unsigned tall clock that descended in the Schley family of Frederick County (figs. 30, 31) and on a later example with a movement by John Fessler, Sr. (figs. 32, 33). These historical associations are extremely important because the Schley and Fessler families were associated. In 1811, John Fessler, Jr., set up his clockmaking business in the house of George Schley, whose brother John Jacob (1751–1829) was a “Joynter.”[36]

The Schleys’ parents, John Thomas (1712–1789) and Marta Margareta (Wintz von Wintz) (1712–1790), emigrated from Weurtzheim, Germany, and settled in Frederick Town in 1745. The records of the German Reformed Church refer to the father as a “schoolmaster,” but in the first list of lot holders he is also described as an “innholder.” John Thomas reportedly built the first house in Frederick Town in 1746.[37]

John Jacob presumably served a seven-year apprenticeship beginning at the age of fourteen and probably began working independently about 1772. In that year, he received 250 board feet of walnut from Joseph Doll. In 1778, Schley married Anna Maria Shellman (1754–1843). Her father, John Mattheus (1724–1795), was a Rhenish joiner who arrived in Frederick Town by 1751. It is possible that Schley trained with Shellman since apprentices often married into the families of their masters.[38]

A tall clock with a movement by John Fessler, Sr., and a history of descent in the Shellman family (figs. 32, 33) provides an additional link between the desk-and-bookcases (figs. 27, 29) and the Schley family clock case (figs. 30, 31). All of these pieces have similarly shaped tympana, and the clock cases have rosettes with spiraling leafage, fretwork friezes, and cornice moldings with small ogee elements, broad flat dentils, and deep coves. Although it is impossible to attribute this furniture to a particular artisan, the physical evidence and histories associated with these objects point to a member (or members) of the Schley or Shellman families.[39]

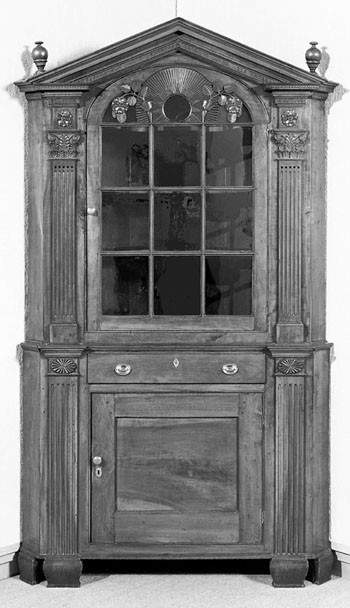

Closely related to the preceding group are two corner cupboards (figs. 34–36), one of which was found near Myersville in Frederick County (fig. 34). Both cupboards have finials similar to the one on the Fritchie desk-and-bookcase (fig. 27), and one has a boldly carved fan in the arch of its upper door (figs. 36, 37). In form, the cupboards are virtually identical. Both have a pitched pediment with a Corinthian entablature, an arched, glazed door flanked by fluted pilasters, and a single drawer and paneled door below. The cupboard illustrated in figure 34 has replaced feet, but the original ones undoubtedly resembled those on the other example.[40]

The pediments and doors of these cupboards have a variety of classically inspired architectural details that set them apart from other western Maryland furniture: inlaid dentils and carved borders, finials, modillion blocks, rosettes, and Corinthian capitals. The only other Corinthian capitals in the region are on the entrance to Thomas Maynard’s stone house built near New Market, Maryland, in 1809. His house has an eight-panel front door flanked by fluted Corinthian pilasters and capped by a six-light transom with a dentiled hood. Designs for architectural “frontispieces” may have provided the inspiration for these cupboards. Their overt architectural character, relationship to the entrance of the Maynard house, and relatively coarse construction suggest that they were made by house joiners rather than cabinetmakers.[41]

Because the backboards extend only as high as the upper edge of the canted corners, the pediment head of each cupboard has a central ridge that slopes downward and flattens as it approaches the back corner. To provide an additional nailing surface and to reinforce the joint along the upper back edge, the joiner attached beaded battens at the juncture of the backboards and top. He also fitted each cupboard with serpentine shelves (with serpentine spoon slots), aligning them with the muntins of the doors.

With their complex ogee feet and superimposed pilasters, the corner cupboards illustrated in figures 38 and 39 are stylistically related to the preceding examples (figs. 34, 36). Both have molded keystones and double rows of offset dentils—details that occur with some frequency on other pieces from Frederick County. R. T. Haines Halsey probably purchased the cupboard illustrated in figure 38 in Maryland during the 1920s for collector Francis P. Garvan. The other example (fig. 39) descended in the Mahoney family of Frederick County. Several related cupboards have appeared in the marketplace over the last several years, including one inscribed “Frederick, Maryland.”[42]

A tall chest inscribed “Francis Keyes” (figs. 40, 41) has several details that tie it to the Garvan and Mahoney cupboards. Keyes was an attorney who lived in Loudon County, Virginia, directly across the Potomac River from Frederick County. His chest has a broad, coved cornice, offset dentils, an applied shell with convex lobes on the top center drawer, and stop-fluted quarter-columns. The latter detail is common on furniture from northern Virginia, particularly the Winchester area, and it may have been introduced to western Maryland by tradesmen migrating up the Shenandoah Valley (figs. 16, 47). The chest also has a drawer support system commonly found on furniture from the Valley of Virginia, southeastern Pennsylvania, and Tennessee. The supports are dadoed and nailed to the sides of the case and tenoned into rails at the front and rear. This framework helps stabilize the case and provides a nailing surface for the vertical backboards.[43]

A related group of furniture made in Washington County, Virginia, in the southeastern corner of the state, has offset dentils, stop-fluted quarter-columns, and construction details similar to the Keyes chest and the corner cupboards illustrated in figures 38 and 39. These relationships may be more than circumstantial. Francis Keyes owned land in Washington County, Virginia, and married there in 1801. His wife, Polly, was the daughter of Joseph Meek of Hagerstown. Members of the Meek family and certain relatives in the Grubbe family were cabinetmakers who moved from Maryland to Washington County, then to Missouri during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.[44]

Like styles and construction techniques, furniture also moved from region to region. An exceptional tall case clock with unusual appliqués on its tympanum (figs. 42, 43) is one of two related examples found in Shepherdstown, (West) Virginia. Although several scholars have attributed the clocks to Shepherdstown, evidence suggests that they were influenced by styles from western Maryland if not actually made there. The profile of the pediment, fluted appliqués on the edges of the tympanum, urn finials with broad, undercut rims, and superimposed quarter-columns (fluted above plain) are details associated with early Frederick Town production. The clock also has several highly individualistic features, including the stylized, chip-carved volutes at the scroll junctures, the magnolia pods (or stylized pine cones) capping the finials, the fluted, cylindrical pediment scrolls, and the stylized baroque keystone squeezed between the open rounds of the pediment.

A Frederick Town origin for the preceding clock (fig. 42) is strongly suggested by a related case with a movement by John Fessler, Sr. (fig. 44), and another, derivative of the previous two, with a movement by Valentine Steckell of Frederick Town (figs. 45, 46). Many artisans and their apprentices moved freely throughout the southern backcountry. Hagerstown clockmaker George Woltz owned several pieces of property in Shepherdstown, and other Maryland artisans are known to have spent time along the southern banks of the Potomac.[45]

An elaborate architectural corner cupboard (figs. 47, 48) provides additional evidence for attributing the clock case shown in figure 42 to western Maryland. Although the spandrel appliqués on the cupboard are considerably more sophisticated than the tympanum carving on the clock (figs. 43, 48), both designs feature C scrolls connected by chip-carved volutes. Another cupboard with related tympanum carving, stop-fluted pilasters, and gadrooned moldings has a history of descent in the Brindle family of Hagerstown. Like other cupboards from the region, the example shown in figure 47 has plinth feet, an interior pilaster at the apex of the back, and stop-fluted pilasters. Similar details also occur on corner cupboards from northern Virginia.

The painted corner cupboard shown in figures 49 and 50 illustrates the difficulty of separating furniture made in western Maryland from contemporary northern Virginia work. The cupboard shares a number of stylistic features with Frederick County examples, including an elaborate, stepped cornice with an applied fret and Greek key molding, a large molded keystone surmounted by a truss with guttae blocks and a fluted plinth, stop-fluted pilasters and cants, and a crossetted architrave. The floral carving is related in design to that of two corner cupboards (figs. 34–37) and a Windsor chair with a Frederick Town history (figs. 51, 52). No other Frederick County cupboard has complex mullions like this example; however, a desk-and-bookcase by Martinsburg, (West) Virginia, cabinetmaker John Shearer has doors that are similar. He made furniture for several Frederick Town residents and is believed to have moved there during the early nineteenth century. Although many furniture historians have described Shearer’s work as “bizarre” and “eccentric,” furniture historian Philip Zea has shown that his furniture has Scottish antecedents. The Scots-Irish were clearly a powerful cultural force in the southern backcountry, but their specific contributions to regional British material culture remain poorly understood.[46]

In addition to case furniture, cabinetmakers in western Maryland constructed a large number of chairs. The most common chair design in the region has a straight crest rail and a solid vase splat with a half-round bead on the shoulders (fig. 53). Although the basic design of the back appears to be derived from British or Chesapeake Bay region chairs, the shape of the arms and arm supports and the wedged, through-tenon construction (the seat rails pierce the back stiles) probably reflect Pennsylvania influences. Several variations of this chair design exist. An example that belonged to George Woltz has pointed “beads” on the shoulders of the splat (fig. 54), and a related set with pierced splats and serpentine crests has a Frederick Town history (fig. 55).

Another group of straight-leg chairs differs only slightly from the standard Frederick County model (fig. 56). These chairs have a saddle-shaped crest rail with flared ears and a simple flared splat with three vertical piercings, each interrupted with a rounded ball or arch. Simple box stretchers and more complex “H” stretchers both appear on chairs in this group. When arms are added, they roll gently outward and have simple, rounded supports. Like the previous group, these chairs also have through-tenons at the juncture of the seat rails and rear stiles.

The chair illustrated in figure 57 is clearly related to the previous examples in the shape of the splat, in the configuration of the legs and stretchers, and in the through-tenons of the seat frame. It differs from them, however, in having parallel stiles, heavier stock, scrolled ears, and ogee shaping on the seat rail. The latter detail brings to mind the ogee shaping between the feet of the Myer clock (fig. 21).[47]

The finest Frederick County chairs, and those most clearly based upon Pennsylvania examples, consist of a set of six carved examples with pierced splats, shell-carved crests and knees, and claw-and-ball feet (fig. 58). They were apparently presented to All Saints Parish in Frederick Town by vestryman George Murdock (1768–1804). That these chairs were actually constructed for the church is strongly suggested by the symbolic dogwood blossom carved in the front rail. Dogwood blossoms are well documented on furniture made specifically for an ecclesiastical context. A chancel chair ordered by the vestry of Saint Michael’s Church in Charleston, South Carolina, from the Philadelphia firm of Beal and Jameison in 1816 has dogwood blossoms carved on the crest and arm terminals.[48]

A remarkable corner cupboard (figs. 59, 60) with a variety of details garnered from different sources shows how the distinct character of western Maryland furniture reflects the complex overlay of cultures within the region. Although its form and specific details suggest the work of a creative, and perhaps eccentric, artisan, the cupboard is, nevertheless, a composite of regional influences. The claw-and-ball feet, cabriole legs, and shell-carved knees, which resemble those on the chairs from All Saints Parish, are clearly based on Pennsylvania prototypes. Other details, however, are borrowed from the larger vocabulary of ornament popular in western Maryland and northern Virginia during the late eighteenth century. The three floral finials on the corner cupboard are related in concept to the frieze appliqués on the cupboard shown in figures 49 and 50, to the carved crest rail of the Windsor chair illustrated in figures 51 and 52, and to the carved mullions on the doors of the cupboards shown in figures 34–37. Like the corner cupboard with the C-scroll appliqués (figs. 47, 48), this example has a gadrooned ovolo capping the cornice (figs. 59, 60). It also has intaglio carving on the tympanum, which reflects the strong regional taste for naturalistic ornament on friezes and pediments. Other western Maryland details on the corner cupboard include the layered rosettes, shaped dentils, and crossetted architrave for the arched door. Similarly, the arched panels of the lower doors echo the Gothic interiors of fall-front desks made by John Shearer of Martinsburg, (West) Virginia. Other features of the cupboard appear to be unique in this region’s furniture: the carved bead-and-reel molding on the cornice, the drill-work ornament on the outer finial plinths, and the unconventional mullion design.

Like the corner cupboard, many of the pieces discussed in this study represent the work of regional artisans who were challenged by the influx of people from Pennsylvania, eastern Maryland, and northern Virginia, who constantly weighed the new ideas they introduced, and who blended Germanic and British cultural traditions with their own personal experiences. Collectively, these influences compelled these artisans to produce objects that were distinctively their own yet reflected the tastes of the larger region in which they lived. This formula, repeated time and again at the crossroads of western Maryland, produced one of the most distinctive schools of furniture in eighteenth-century America.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article the authors thank Joseph Adkins, John Bast, James Beachley, Luke Beckerdite, Collin Clavenger, Mary Ruth Coleman, Janet Davis, Julie Dennis, Gail Denny, William Voss Elder, III, Rebecca Fitzgerald, J. Michael Flanigan, Elizabeth Graff, Lisa Grygiel, Sean Guy, Wesley Harding, Ronald Hurst, Carrol H. Hendrickson, Jr., Sally and Roddy Moore, Jonathan Prown, Jackie Rogers, Susan Shames, N. Kenzie Smith and Sons, Bruce Shuettinger, John J. Snyder, Jr., Christine Steltzer, Marie Washburn, Gregory Weidman, James Whisker, Jean Woods, and Mr. and Mrs. William Yinger. We are especially grateful to the staff at the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts—Jennifer Bean, Frank Horton, Brad Rauschenberg, Martha Rowe, and Wesley Stewart—and to Edward and Helen Flanagan.

Archives of Maryland, Proceedings of the Council of Maryland, 28:25–26. Lord Baltimore described this area as “the back lands on the Northern and Western boundaries of our said province not already taken up between the Rivers Potomack and Susqauehana.” Archives of Maryland, Proceedings of the Council of Maryland, 46:142–44.

Heads of Families at the First Census of the United States taken in the Year 1790, Maryland (Baltimore, Md.: Southern Book Company, 1952), p. 9. J. Thomas Scharf, History of Western Maryland, 2 vols. (1882; reprint ed., Baltimore, Md.: Regional Publishing Company, 1968), 1:36, 396. William Harris Crawford Journals, June 4, 1813, Crawford Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Daniel Wunderlich Nead, The Pennsylvania-German in the Settlement of Maryland (1914; reprint ed., Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1975), pp. 54–55. The name “Elizabeth Town” fell from favor during the 1780s, appears only sporadically during the 1790s, and all but disappears by 1800. Eddis, Letters from America, pp. 133–34.

For information on the Loose and Beachtel families and “White Oak Forest Farm,” see David and Susan Miller, Loose Family Genealogy, unpublished, undated manuscript on file at the Washington County Historical Society, Hagerstown, Maryland.

For the history of the desk, see MESDA research file S-9745.

Joseph Doll’s ledger contains the following entries for bedsteads: Henry Shover, October 1773, “one pair of bedSteds Painted Green... £1.5”; Francis Mantz, January 10, 1775, “one bedstid . . . 12s”; John Brunner, Jr., July 8, 1775, “one pair of bedStids at 3 dollars . . . £1.2”; John Hummel, March 29, 1777, “one Little bedStid . . . 12s”; Michael Christ, February 1787, “one bedStid with high Posts painted blue with four Scroos . . . £2.7.6. ”Doll’s ledger contains the following entries for cradles: Christian Weaver, November 26, 1774, “one Greadle to Rog his Chylde . . . £1”; John Brunner, Jr., July 8, 1775, “a Creadle . . . 18s.”

Joseph Doll’s ledger contains the following entries for case furniture: John Brunner, Jr., February 6, 1775, “one Kitchin Cobert . . . 3.15”; Caspar Mantz, September 26, 1775, “one Chest with drawers for ditto [daughter Caety] . . . £3.5”; Peeter Brunner, February 16, 1776, “one Kitchen Dresser with glas and furniture . . . £ 7”; John Kyle, March 7, 1789, “one Corner Cobbert . . . £4.10.”

Joseph Doll’s ledger contains the following entries for coffins: John Breidenbach, May 15, 1775, “To one Coffin . . . 10s”; Peeter Brunner, December 8, 1775, “To one Coffin . . . 10s”; Peeter Brunner, February 16, 1776, “To one Coffin for his Son John at 25/ . . . £1.5”; Christian Weaver, November 26, 1776, “One Smol Coffin for his Childe . . . 5s”; Peeter Brunner, March 18, 1777, “To one Coffin for his Father . . . 1.15”; John Brunner, Jr., undated, “one Coffin for his Father . . . £1.10”; Phillip Friegi, January 14, 1788, “One Coffin for M [illegible] Wittman . . . £1.5.” In 1774, Doll charged Thomas Preise 1s 6d for “mending Two Chairs.” On June 16, 1790, Doll charged Henry Cronier 2s 9d for “Making a Sidepeese to his bedStid paint blue.”

Joseph Doll Ledger, p. 27. Jennings, Schley Family, p. 101. Reed and Burns, In and Out of Frederick Town, p. 51. Williams and McKinsey, History of Frederick County, 2:1314.

For information on the Meeks and Grubbe families, see Danny Morris Fluhart, The Meek Family of Washington County, Virginia (Waldorf, Md.: by the author, n.d.), n.p. The authors thank Roddy Moore for information on the Keyes, Meeks, and Grubble families and the group of furniture from Southwest, Virginia.