Joined chest attributed to John Clawson or an apprentice, Providence, Rhode Island, 1650–1680. Red oak. H. 31 1/4", W. 52", D. 24 1/4". (Courtesy, Rhode Island Historical Society.) Brackets are missing at the front.

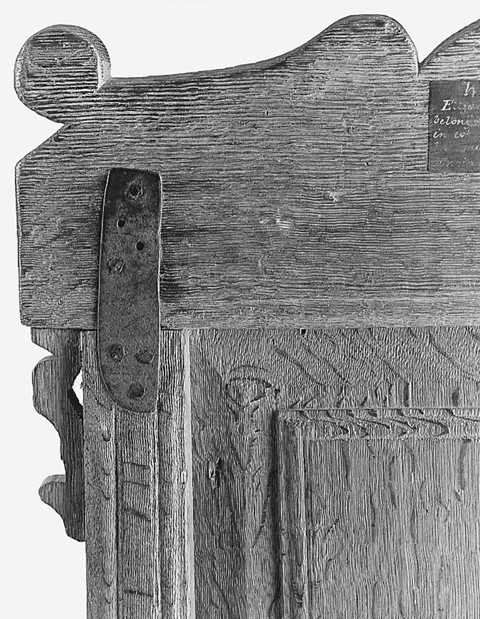

Detail of a tabled front panel and ogee molding on a muntin on the chest illustrated in fig. 1.

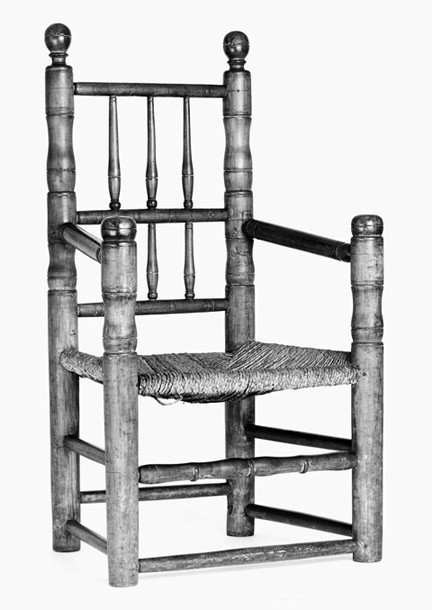

Joined great chair, probably Providence, Rhode Island, 1660–1680. Oak. H. 437/8", W. 24", D. 18". (Courtesy, National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Martin House Farm, Swansea; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair descended in the Cole family of Rehoboth and Swansea.

Detail of the back panel of the chair illustrated in fig. 3. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the reverse of the back panel of the chair illustrated in in fig. 3. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the upper turning on the front post of the chair illustrated in fig. 3. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Joined chest with drawer, probably Providence, Rhode Island, 1650–1680. Red oak, chestnut, white pine and maple. H. 271/2", W. 49", D. 201/4". (Courtesy, Rhode Island Historical Society, bequest of William I. Cranston in memory of his father, mother, wife, and brothers Raymond E. Cranston and Winthrop M. Cranston; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a carved panel on the façade of the joined chest illustrated in fig. 7. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Joined great chair, Plymouth County, Massachusetts, 1640–1690. Oak and pine. H. 44 1/4", W. 28 1/4", D. 22". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair descended in the Burgess family of Duxbury, Sandwich, Yarmouth, and Rochester. The upper back posts, back panel, brackets, and crest rail are restored.

Detail of upper turning on the front post of the chair illustrated in fig. 9. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Turned great chair, probably Kingston, Rhode Island, 1670–1710. Maple. H. 43 1/8", W. 24 5/8", D. 18". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) This chair descended in the Case and Clarke families of Westerly and Kingston.

Turned chair, probably Kingston, Rhode Island, 1680–1720. Maple, red oak, and ash. H. 39 1/8", W. 21", D. 14 1/2". (Courtesy, Rhode Island School of Design; gift in memory of Mercy Congden Brown by her four grandaughters; photo by Erik Gould.) This chair descended in the Congden or Brown family of South Kingston. www.risd.edu

Turned great chair, probably Rhode Island, 1650–1700. Ash. H. 42", W. 24", D. 15". (Courtesy, Connecticut Historical Society; bequest of George Dudley Seymour.)

Turned great chair, probably Rhode Island, 1650–1700. Ash. H. 41", W.24 1/2", D. 21". (Private collection; photo, Robert F. Trent.)

Board chest, Rhode Island, 1686. Pine and chestnut. H. 23 1/8", W. 50 1/2", D. 19". (Courtesy, Rhode Island School of Design, gift of Dr. and Mrs. William Colaiace; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chest descended in either the Remington or Rhodes family of Pawtucket. www.risd.edu

Joined table attributed to Christopher Townsend, Newport, Rhode Island, 1739–1749. Maple and white pine. H. 28 1/2", W. 42", D. 35 3/4". (Courtesy, State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This table is one of a pair. The tops and feet are missing on both. The illustrated example has traces of blue paint. Christopher Townsend was the principal joiner involved in the construction of the Colony House during the mid-1740s.

Detail of a leg on the table illustrated in fig. 16. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a newel post in the Colony House showing the same turning sequences found on the legs of the table illustrated in figs. 16 and 17.

Joined table, possibly Newport,Rhode Island, 1720–1750. Maple. H. 217/8", W. 201/2", D. 145/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Oval leaf table, possibly Newport, Rhode Island, 1720–1750. Woods and dimensions unrecorded. (Courtesy, Redwood Library, Newport, Rhode Island.) This table descended in the Easton family. Its present location is unknown.

Oval leaf table, possibly Newport, Rhode Island, 1720–1750. Maple. H. 28 1/2", W. 47 3/4", D. 57 1/4". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation.)

In the twenty-one years since Robert Blair St. George’s The Wrought Covenant appeared, only a few new objects from the earliest period of southeastern Massachusetts and Rhode Island have come to light. Some of these new finds are significant, and several of the objects published before now merit renewed study. For the sake of brevity, this article will omit illustrating some of the warhorses in St. George’s study, notably the Benedict Arnold great chair, the Bristol pew door, and the Little Compton communion table.[1]

New interest in furniture made by the Dutch in America has codified several New York furniture forms. Peter Kenny has written monographs about the kas and variants of the leaf table, and Robert Leath has speculated upon possible Netherlandish antecedents of several monuments of southern furniture, notably a joined great chair at the Wadsworth Atheneum and a cupboard whose present location is unknown.[2]

In this regard, renewed attention must be paid to the Field family joined chest at the Rhode Island Historical Society (fig. 1). In The Wrought Covenant, St. George speculated that all Rhode Island furniture owed a debt to the joinery and turning traditions of Plymouth, Massachusetts; however, the entry about the Field family chest in New England Begins speculates that this object was made by Dutch joiner John Clawson (fl. 1646–1660) of Providence. If this attribution is correct, the Field chest is the only major Netherlandish joined chest from seventeenth-century America.[3]

One of the most notable characteristics of seventeenth-century Dutch joinery is its exquisite quality. Northern European joinery was far superior to anything executed by woodworkers trained in the English tradition. This superiority entailed all aspects of production, from concept, through wood selection, to standards of fabricating parts, joint cutting, and decorative aspects like moldings and carved motifs. This level of workmanship is evident in the four New York oak kasten discussed in Kenny’s monograph, and it is manifest in the Field chest.[4]

The Field chest belongs to the most common type of better Netherlandish joined chest, which features three or four tabled panels in the facade, two or more rows of imbricated crease moldings on the facade members, and deep, carved brackets. Some have joined lids, whereas others have multi-board oak lids with pintel or iron strap hinges, full-length splines or registration pegs between the boards, and often a molded edge. This chest type continued in production well into the eighteenth century and is comparable to the elaborate, board-seated turned chair as a Dutch Mannerist survival. The Field chest exhibits many of the classic, labor-intensive details that rendered this long-lived northern European furniture form a middle-class luxury. First, the stock was all full-dimension; that is, no lumber was used that came up short of the intended full dimensions of the stock. Second, the tabled panels of the facade, with an ogee molding around the edges of the table (fig. 2), were made with a panel or raising plane that became common in American house joinery after 1710 but was rare prior to that date. One impulse behind using this tool, other than habitual precision, was the way in which the muntins between the panels were ornamented. Not only were they run with large ogee moldings on the exterior, but the same molding appears on the interior or reverse side of the stile. The molding also appears on the interior surfaces of the rear muntins but not on the exterior. Because the front muntins were molded on both sides, the grooves for the panels had to be located with some precision and the edges of the panels had to taper to a uniform, precise thickness.[5]

Another lavish detail involves the way the floorboards were made. In most English chests, floorboards were inserted after the case was assembled. In some cases, the floorboards were merely nailed in rabbets. In others, the separate boards were slid into grooves in the front and side rails and then nailed to the rear rail. Often this last procedure exploited a tapered center board that forced the other boards to each side until they were snug; presumably the center or key board was left a bit long so that it could be trimmed until the optimum fit was achieved. The edges of the floorboards that fit in grooves were informally planed to a feathered edge. All in all, most such bottoms were rough affairs.

In the Field chest, an entirely different approach was used. The front-to-rear boards were trapped in grooves on all four sides so that they had to be inserted into the case as it was being assembled. Further, the edges were not roughly feathered but were sawn to a uniform thickness on their shoulders, then planed smooth to make a rectangular edge that completely filled the groove all around. Obviously this work parallels, to some degree, the extraordinary care seen in the concept and execution of the tabled and molded panels in the facade. Less obviously, the construction of the chest’s bottom is analogous to the back construction of kasten.[6]

One curious note in the chest’s appearance is the lid, constructed of riven boards jointed by full-length splines. Why the maker chose to leave the wedge-shaped cross-section in the top boards rather than plane them to a uniform thickness is unclear. Finally, furniture historians might well be disappointed that the brackets of the chest are lost, because Dutch brackets tend to have more dramatic scroll outlines and more detailed carving than English versions.

A tabled panel is also seen in the famous Cole family joined great chair (figs. 3-6). This magnificent object has a single, large back panel carved with a rondel inscribed in a diamond and abstract foliate tendrils (fig. 4). The reverse side of the panel is tabled, with molding run on the table edges (fig. 5). Was this chair also made by a workman of Dutch extraction?

A closer examination of the panel suggests that it was not made with a panel plane but was rendered by feathering the edge with a block plane (figs. 3, 4). This conclusion is reinforced by an examination of the Cranston family chest, which was carved by the same hand (figs. 7, 8). The Cranston chest, whose history provides the basis for attributing the Cole chair to Providence, displays no Netherlandish traits but seems to be a provincial variant of London-style joinery. The tabling that one might have wished to find on the reverse sides of the front panels is not present, and the only hint of such an approach is the deep chamfering of the rear panels. The cruciform side panels of the facade and the archway motif of the center panel seem, on first inspection, to be straightforward indices of the London style. The bulk of the decorative elements (save for the replaced maple drawer knobs and the original maple pendant in the center panel) is oak. The lid is pine, and the drawer bottom and storage compartment floor are chestnut.

Upon further examination, the pyramidal bosses and the large, blank surfaces of the plaques that form the archway on the Cranston chest’s center panel are strongly reminiscent of joinery associated with the New Haven Colony in Connecticut. In particular, the entire central panel bears an uncanny resemblance to the door panels and side panels of the trapezoidal storage areas of four New Haven Colony cupboards illustrated and discussed in Patricia E. Kane’s Furniture of the New Haven Colony: The Seventeenth-Century Style. In his monograph, St. George included a chest with two drawers that descended in the Hall family of Taunton and the Barrows family of New Bedford, which is squarely in the New Haven Colony manner. This connection also suggests a strong tie between that region and the Narragansett Bay area.[7]

The lack of strong Dutch influence in the Cranston chest’s construction and design, and the possibility of New Haven influence upon it, are further complicated by a number of other factors. The Cole family chair bears no relationship to the two joined great chairs in the New Haven Colony manner; however, it relates very strongly to chairs and chair-tables from Plymouth Colony. The aforementioned Benedict Arnold chair at the Newport Historical Society is a lighter version of the same design, and St. George attributed it to Marshfield, Massachusetts.[8]

A second object that was not known at the time of St. George’s study is the Burgess family joined great chair (fig. 9). This piece, which is strikingly close to the Cole chair in weight, proportions, and detailing, has a provenance beginning with either Thomas Burgess (d. 1685) of Duxbury and Sandwich or his son John Burgess (1627–1701) of Yarmouth. Comparison of the turnings on the Burgess chair (fig. 10) with those of the related example (fig. 6) suggests that the Burgess turnings are more closely allied to those of the Benedict Arnold chair at the Newport Historical Society. Curiously, both the Burgess chair and the Arnold chair experienced exactly the same losses to the upper posts, back panels, brackets, and crest rails. One interesting sidenote to the Burgess provenance is that the second and third generations of the Burgess family also included residents of Newport and Little Compton in Rhode Island. A noteworthy detail is the waist molding, which is identical to those of Plymouth County case pieces.[9]

The upshot of these stylistic complexities is that the Cole chair and the Cranston chest were probably made in Providence, that they reveal influences from Providence joiner John Clawson, from New Haven Colony, and from Plymouth Colony, and that they remain enigmatic as interpetive devices for any history of Rhode Island furniture. The only trait that relates to later regional production is the use of chestnut in the Cranston chest.

Two early turned chair traditions can be associated with Rhode Island. The first is represented by two armchairs and a rare side chair associated with Kingston. The Case/Clarke armchair (fig. 11), published by Benno M. Forman, has spherical finials, softly modeled urns on the posts, and two tiers of simple vasiform spindles in the back. A nearly identical armchair once on loan at the Hempstead House in New London, Connecticut, and illustrated in Helen Comstock’s American Furniture: Seventeenth, Eighteenth, and Nineteenth Century Styles, has no history. It has slightly more detailed spindles and original turned feet. The Brown/Congden side chair (fig. 12) seems to be later in date than the two armchairs but has elaborately modeled back spindles of robust ogee profile. Patricia E. Kane has suggested that some relationship exists between these Kingston chairs and shop traditions from the Connecticut coast.[10]

A second turned chair tradition is represented by two major armchairs that have no exact provenance other than a vague history for one chair of having been recovered in Fall River, Massachusetts, about 1912 (figs. 13, 14). Both chairs are almost identical, save for minor variations in the turned top back rail. They feature spectacular spherical finials with pronounced flanges underneath, heavy urn turnings on the posts, and one row of bilaterally symmetrical vasiform spindles in the back. The example illustrated in figure 13 has the original spherical pommels or handgrips. Perhaps the most striking feature of both chairs is their built-in layback, which is quite pronounced and is paralleled only in chairs from Norwich, Connecticut, and from Dutch New York.[11]

Rhode Island’s only dated seventeenth-century board chest is distinguished by the presence of a chestnut backboard (fig. 15). Along with the Cranston chest (fig. 7), this example represents the first evidence of this widely recognized regional wood preference. Because it belongs to a genre that ordinarily is identified with either Plymouth County or the Connecticut River Valley, and also because its faint ornament photographs poorly, this plain chest deserves more extensive verbal description. The lid of the chest, which has snipebill hinges, originally had only internal battens run with a thumbnail molding; the present external cleats are a later addition. The feet are the simplest V-cuts on extensions of the sides. The till is missing. The front has a variety of ornaments, including crease moldings, date numerals executed with a multi-toothed punch, and a border made with a zig-zag arc tool similar to, if not identical with, a leatherworker’s pinking tool.[12]

A pair of square table frames (fig. 16) that have been in the Colony House in Newport for well over a century may, in fact, have been part of the original judicial furniture of the building, built between 1739 and 1749. A photograph dated 1886 in a private collection in Providence shows the Jury Room of the Colony House with various original Windsor chairs and one of the square tables. It is evident that the table had a replaced top with rounded corners at that time. Both bases were provided with a single top that bridges them by cabinetmaker Douglas Campbell in the late 1970s, but both tables likely had individual, multi-board oak tops originally. The Tuscan Doric columns on the posts (fig. 17) are severe and are correct by neo-Palladian standards. This design, which is repeated on the newel posts of the Colony House stair (fig. 18), suggests that the tables are contemporary with the building and that their legs and newel posts are by the same turner.[13]

The last major group of early Rhode Island furniture to be discussed here is a group of small joined tables (fig. 19) and oval leaf tables (figs. 20, 21). All are made of maple and feature distinctive turnings with long cylindrical necks punctuated by a thin ring, a strong ball turning, a reel, and a second ball. This stylized vasiform turning is complemented by pronounced vasiform feet on those examples that preserve them. The only documented object from this group is an oval leaf table that descended in the Easton family of Newport (fig. 20). The table formerly was loaned to the Redwood Library by its owner, Cornelius C. Moore (1885–1970), and was bequeathed by him to Providence College. Benno M. Forman and the author examined the table at the Redwood Library and Atheneum in 1973. Photographs of the Easton table show that it is related to oval leaf tables at the Chipstone Foundation (fig. 21) and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as to those in a number of private collections. Winterthur Museum owns several of the small tables, which are raked in one direction only. As yet no exact analog for the turning has been found in stairway balusters, although examples in the Christopher Townsend house in Newport suggest that this area might be a good avenue of future investigation. The tables remained in production long enough to undergo attenuation of the basic turning. Surprisingly, none of the standard early Rhode Island Windsor leg turnings relate to those of the tables.[14]

This brief survey of the earliest Rhode Island furniture has not furnished any striking new objects, but several of the insights regarding stylistic sources and dating may lead to more profound discoveries in the future. Above all, Robert Blair St. George is to be commended for his thorough fieldwork in the late 1970s, a task made more difficult by the fact that Rhode Island’s probate is scattered among the towns rather than concentrated in a county system.

Robert Blair St. George, The Wrought Covenant: Source Material for the Study of Craftsmen and Community in Southeastern New England 1620–1700 (Brockton, Mass.: Brockton Art Center & Fuller Memorial, 1979).

Peter M. Kenny, Frances Gruber Safford, and Gilbert T. Vincent, American Kasten: The Dutch-Style Cupboards of New York and New Jersey 1650–1800 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1991); Peter M. Kenny, “Flat Gates, Draw Bars, Twists, and Urns: New York’s Distinctive, Early Baroque Oval Tables with Falling Leaves,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1994), pp. 107–36; Robert A. Leath, “Dutch Trade and Its Influence on Seventeenth-Century Chesapeake Furniture” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1997), pp. 21–46.

St. George, Wrought Covenant, p. 65. New England Begins: The Seventeenth Century, edited by Jonathan L. Fairbanks and Robert F. Trent, 3 vols. (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1982), 2: 210–11.

Kenny, Safford, and Vincent, American Kasten, pp. 36–43.

Although Dutch chests of the type being discussed commonly circulate on the antiques market, they are not well represented in European museums. One of the best selections of them in print is in Katalog Der Möbelsammlung (Flensburg, Germany: Städtisches Museum, 1976), p. 101, nos. 308–11.

This construction, known as a “clapboard back,” is illustrated in Kenny, Safford, and Vincent, American Kasten, p. 43.

Patricia E. Kane, Furniture of the New Haven Colony: The Seventeenth-Century Style (New Haven, Conn.: New Haven Colony Historical Society, 1973), pp. 24–31; St. George, Wrought Covenant, p. 66. Two additional chests by the maker of the Cranston family example are illustrated in Wallace Nutting, Furniture Treasury (New York: Macmillan Co., 1928), no. 28, and in the advertisement by Bernard and S. Dean Levy in Antiques 155, no. 6 (June 1999).

St. George, Wrought Covenant, p. 35.

Memorial of the Family of Thomas and Dorothy Burgess (Boston: T. R. Marvin & Son, 1865), passim.

Benno M. Forman, American Seating Furniture 1630–1730 (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1988), pp. 108–9; Helen Comstock, American Furniture: Seventeenth, Eighteenth, and Nineteenth Century Styles (New York: Viking Press, 1962), fig. 21; Christopher P. Monkhouse and Thomas S. Michie, American Furniture in Pendleton House (Providence: Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, 1986), pp. 144–45.

George Dudley Seymour’s Furniture Collection in The Connecticut Historical Society (Hartford: Connecticut Historical Society, 1958), pp. 64–65; Forman, American Seating Furniture, pp. 108–12, 124–28.

William N. Hosley, Jr., and Philip Zea, “Decorated Board Chests of the Connecticut River Valley,” Antiques 119, no. 5 (May 1981): 1146–51; St. George, Wrought Covenant, nos. 11, 12, 13, 14, 23, 24, 25, 26, 44, 71, 78.

John H. Greene, Jr., The Building of the Old Colony House in Newport, Rhode Island, 2d ed. (Privately printed, 1952), n.p. Nancy Goyne Evans, American Windsor Chairs (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1996), figs. 6–17.

Wallace Nutting illustrated one of the small tables in Furniture Treasury (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1928), fig. 2723, although he identified it as a stool; it was owned in Barrington, Rhode Island. The Easton family history of the Moore oval leaf table is recorded in the Benno M. Forman Papers, collection 72, box 7, object entries 58.565, 58.566, 58.567, and 67.1455, Joseph Downs Manuscript Library, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, Delaware. The ownership of the Easton table is recorded in J. Lloyd Hyde and Lorraine Dexter, “The Furniture of the Library,” in Redwood Papers: A Bicentennial Collection, edited by Lorraine Dexter and Alan Pryce-Jones (Newport, R.I.: Redwood Library and Atheneum, 1976), p. 92, as follows: “In the Webster Room also is a beautiful gate-leg table from the collection of Mr. Cornelius Moore and on loan from Providence College.” The college withdrew the table in 1981 and sold it at auction (Christie’s, Fine American Furniture, Silver and Decorative Arts, New York, September 19, 1981, lot 539). The Easton history was not cited in the catalogue. A bequest of New England silver made by Moore to the college was sold in 1986 (see Sotheby’s The Cornelius C. Moore Collection of Early American Silver, New York, January 31, 1986). Some of Moore’s furniture was sold at auction in 1971 (see Parke-Bernet Galleries, Important American Furniture from the Collection of the Late Cornelius C. Moore, Newport, Rhode Island, New York, October 30, 1971). The Chipstone oval leaf table is illustrated and discussed in Oswaldo Rodriguez Roque, American Furniture at Chipstone (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1984), pp. 278–79. Benno M. Forman had informed Stanley Stone, co-founder of the Chipstone Foundation, about the Easton family table. The Metropolitan Museum of Art oval leaf table is illustrated in “Early American Interiors with Contemporary Window Hangings,” Antiques 50, no. 4 (October 1946): 240. One other oval leaf table is illustrated in an advertisement for Bernard and S. Dean Levy, Antiques 136, no. 3 (September 1989). The Christopher Townsend house staircase is illustrated in Michael Moses, Master Craftsmen of Newport: The Townsends and Goddards (Tenafly, N.J.: MMI Americana Press, 1984), p. 71. Evidently dealers and collectors have been aware for over fifty years of the Newport origins of this shop tradition, even though Cornelius Moore’s table was never published; see Albert Sack, Fine Points of Furniture: Early American (New York: Crown Publishers, 1950), pp. 238, 240.