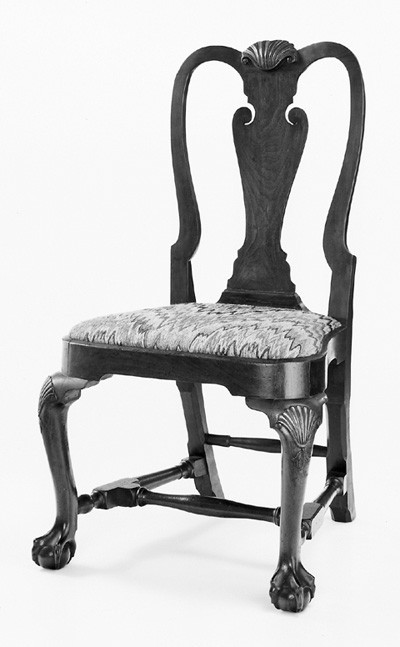

Side chair, Boston, 1710–1720. Maple and oak. H. 47 1/2", W. 18", D. 14 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

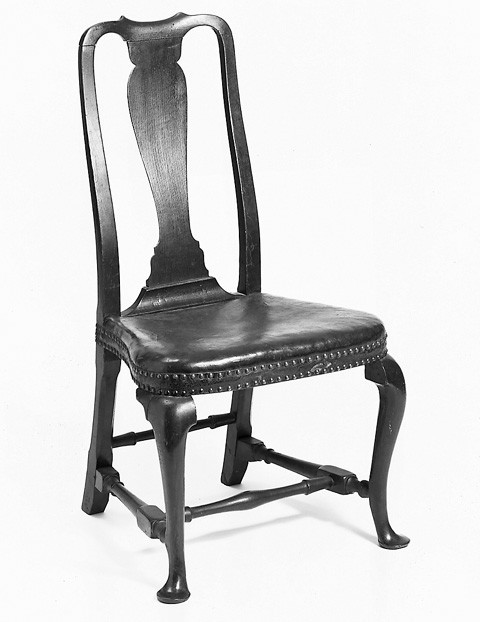

Side chair, Boston, ca. 1725. Maple and oak; original leather upholstery. H. 43 3/4", W. 18 1/2", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Boston, 1710–1720. Maple. H. 45 1/4", W. 17 1/2", D. 14 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Boston, ca. 1725. Maple. H. 43", W. 19", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Britain, ca. 1725. Beech. H. 44 1/2", W. 17 3/4", D. 15 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Boston, ca. 1725. Maple. H. 45", W. 19", D. 15 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Side chair, Boston, ca. 1725. Maple. H. 43 3/16", W. 18 1/4", D. 14 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, Boston, 1715–1725. Maple. H. 46", W. 23", D. 16 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

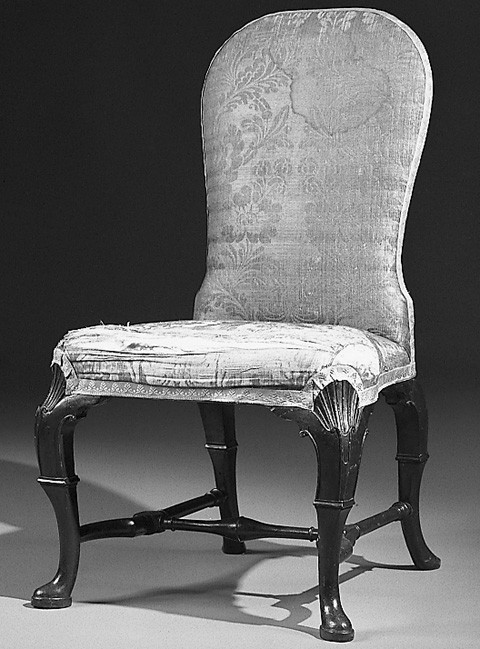

Side chair, London, 1715–1725. Beech; japanned green and gold on a red ground. H. 45 1/2", W. 21 1/2". (Courtesy, Victoria and Albert Museum.)

Easy chair, Boston, 1690–1710. Maple with pine; original foundation upholstery. H. 42". (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Side chair, Boston, 1690–1700. Maple and oak. H. 35 1/2", W. 18 1/2", D. 18 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

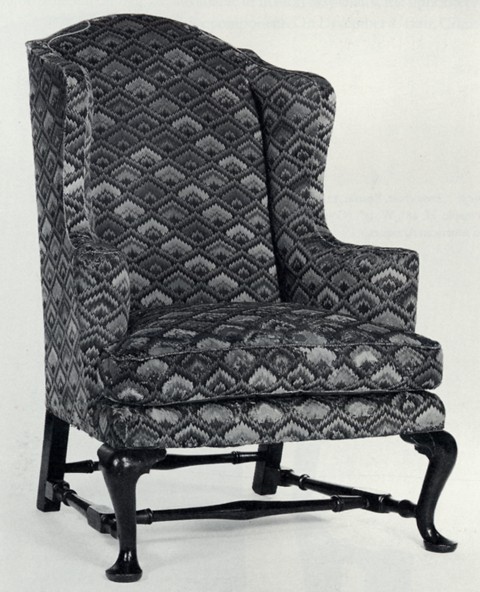

Easy chair, Boston, 1700–1710. Maple with oak. H. 50 3/4", W. 27", D. 21". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum). The feet are worn and have lost their laminated facings.

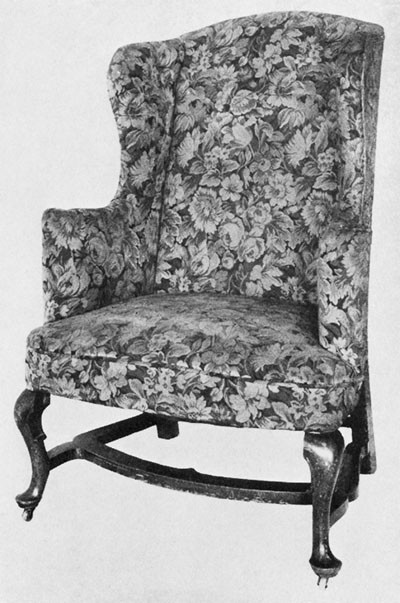

Easy chair, Boston, ca. 1725. Maple. H. 48 1/2", W. 27 3/8", D. 21". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Armchair, Boston, 1725–1730. Birch and cherry. H. 40 3/4", W. 22 7/8", D. 17 1/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; bequest of Dr. and Mrs. Newberry Reynolds.)

Armchair, Boston, 1725–1735. Maple. H. 43 1/4", W. 20 11/16", D. 17". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Side chair, Boston, ca. 1730. Walnut. H. 41", W. 19 3/16", D. 15 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The crest rail may be a replacement.

Elbow chair, Boston, 1725–1735. Mahogany with maple. H. 34 3/4", W. 23", D. 19". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

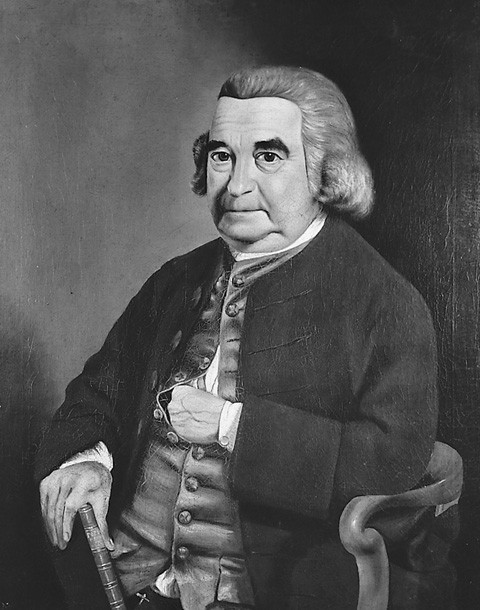

Abraham Redwood, II, attributed to Samuel King, Newport, 1773–1780. Oil on canvas. 42 1/2" x 33 1/2". (Collection of the Redwood Library and Atheneum, Newport.)

Armchair, Boston, ca. 1725–1730. Walnut with maple. H. 43 1/2", W. 23", D. 18 3/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The center stretcher is replaced.

Side chair, Boston, ca. 1725–1730. Walnut with maple. H. 40 1/4", W. 20", D. 16". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Side chair, London, ca. 1720. Walnut with lightwood inlay. Dimensions not recorded. Illustrated in Nicholas Grindley, The Bended-Back Chair (London: Barling, 1990), no. 17.

Detail of the knee carving on the armchair illustrated in fig. 20.

Detail of the knee carving on the side chair illustrated in fig. 21.

Desk-and-bookcase, Boston, ca. 1740–1750, Unknown artist. Mahogany, oak secondary wood. H. 94", W. 41 1/4", D. 24". (Courtesy, Art Institute of Chicago, major acquisitions Centennial Fund.) The feet and one finial are replaced.

Detail of the carved appliqué on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 25.

Side chair, Boston, ca. 1725–1730. Mahogany with maple. H. 41", W. 21 1/4". (Collection at Hunter House, Preservation Society of Newport County; photo, John W. Corbett.)

Easy chair, Boston, ca. 1730. Maple. H. 48", W. 33 3/4", D. 29". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Bayou Bend Collection; gift of Miss Ima Hogg.)

Side chair, Boston, ca. 1730. Mahogany; beech slipseat frame. H. 44", W. 19", D. 21". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Bayou Bend Collection; gift of Miss Ima Hogg.)

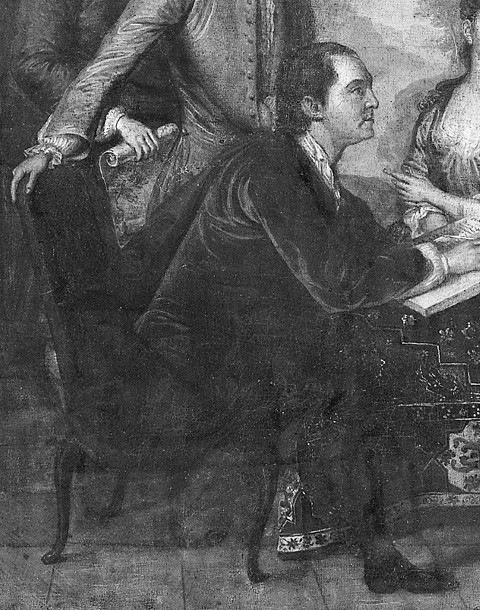

John Smibert, Mary Fitch Oliver and Andrew Oliver, Jr., Boston, 1732. Oil on canvas. 50 1/2" x 40 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Frick Art Reference Library.)

John Smibert, detail of a study for The Bermuda Group, ca. 1729. Oil on canvas. 69 1/2" x 93". (Courtesy, National Gallery of Ireland.)

Backstool from the shop of Thomas Roberts, London, 1728. Walnut. H. 41", W. 23 1/2", D. 25". (Courtesy, Christie’s.)

Backstool, Boston, ca. 1730. Walnut with maple and beech. H. 40", W. 21", D. 25". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The backstool originally had silk upholstery.

Easy chair, Boston, 1730–1740. Walnut with maple. H. 49". (Courtesy G. W. Samaha Antiques, Milan, Ohio; photo Jeffery Dykes.)

Detail of the seat rail and front leg joint of the backstool shown in fig. 33. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Boston, ca. 1735. Walnut and walnut veneer with maple and white pine. H. 38 5/8", W. 20 3/4", D. 18 1/2". (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin Ginsburg, 1984 (1984.21) photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, London, 1725–1735. Walnut and walnut veneer. (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

Easy chair, Boston, ca. 1735–1740. Walnut and maple. H. 44", W. 31", D. 22". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Side chair, Boston, 1735–1755. Walnut. H. 38 7/8", W. 19 3/4", D. 16 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Side chair, Boston, 1735–1755. Walnut with maple. H. 39 5/8", W. 21 3/4", D. 21 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; gift of Mr. & Mrs. George M. Kaufman, Martin E. Wunsch, and anonymous donor.)

Side chair, Boston, 1730–1740. Walnut. H. 41 3/4", W. 20 1/2", D. 20". Illustrated in Anderson Galleries, Colonial Furniture, the Superb Collection of Mr. Francis Hill Bigelow of Cambridge, Massachusetts, New York, January 17, 1924, lot. 142.

Side chair, Boston, 1740–1750. Walnut; maple slip seat. H. 40 1/2", W. 21 3/4". (Courtesy, Moses Brown School.)

Side chair, Boston, 1740–1755. Mahogany; maple slip seat. H. 38 1/2", W. 22", D. 21 1/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Boston, 1735–1750. Walnut. H. 40 3/4", W. 20 5/8", D. 17 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair, Boston, 1735–1745. Walnut. H. 40 3/4". (Courtesy, Wayne Pratt Antiques.)

Side chair, Boston, 1735–1745. Walnut; maple slipseat frame. H. 40 7/8", W. 21 1/16", D. 17 1/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; gift of Miss Dorothy Buhler.)

John Singleton Copley, John Barrett, 1758. Oil on canvas. 50" x 40". (Courtesy, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri; gift of the Enid and Crosby Kemper Foundation F76-52; photo, Jamison Miller)

Side chair, Boston, 1740–1750. Walnut. H. 40 1/4", W. 20 3/4", D. 24". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Easy chair by Clement Vincent or George Bright with upholstery by Samuel Grant, Boston, 1759. Walnut and maple with maple and white pine. H. 46 1/8", W. 33 7/8", D. 21 3/4". (Courtesy, Historic New England/SPNEA; photo, Richard Cheek.) The front feet are replaced.

Easy chair, Boston, 1735–1755. Walnut with maple. H. 48", W. 32". (Courtesy, Leigh Keno American Antiques.)

Easy chair, Boston, ca. 1758. Walnut and maple with maple. H. 46 3/8", W. 32 3/8", D. 25 7/8". (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. J. Insley Blair 1950 (50.228.3) Photograph ©The Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Side chair, Boston, 1735–1745. Walnut. Dimensions unrecorded. Illustrated in Anderson Art Galleries, Philip Flayderman Collection, January 4, 1930, lot 492.

Easy chair, Boston, 1735–1745. Walnut. Dimensions unrecorded. Illustrated in Anderson Art Galleries, Philip Flayderman Collection, January 4, 1930, lot 493.

Robert Feke (1706/1707–1752), John Banister, 1748. Oil on canvas. 50 9/16" x 40 9/16". (Courtesy, Toledo Museum of Art.)

I have seen your sumptuous Buildings, your gallent Furniture, your Costly Clothing, . . . the profuseness of your Tables, and . . . a great deal of other Extravegance, I have been always afraid what the consequence of these things would be. . . . As to Silver and Gold we never had much of it in the Country . . . and of all Men, you in Boston, especially the merchants should be silent as to the matter for you shipped it off, and yet now complain of the want of it. . . . Your Advice as to setting up and encouraging Manufactures we very humbly approve of; and you may depend upon it; we in the Country shall . . . raise our own Provisions and wear clothing of our own making as far as possible and live out of Debt.

In the 1995 volume of American Furniture, historian Neil Kamil showed how Boston merchants and artisans produced and exported vast quantities of leather chairs and other manufactured goods to compensate for the lack of a profitable staple crop. Boston’s mercantile strategy was to assume the role of a British metropolis, and its success hinged on making style a commodity. In a 1707 letter to his New York agent Benjamin Faneuil (b. La Rochelle, France, 1658, d. New York, 1719), Boston upholsterer Thomas Fitch (1668/69–1736) wrote, “leather couches are as much out of wear here as steeple crowned hats. Cane couches or others we make like them . . . are cheaper, more fashionable, easy and useful.” Boston’s shipping industry and broad client networks enabled the city’s merchant upholsterers to dominate the market for seating furniture in New England and New York. By 1700, appraisers throughout the colonies referred commonly to leather chairs as either “Boston,” “New England,” or “Boston made.”[1]

During the first half of the eighteenth century, Boston chairmakers continually developed faster and more efficient ways to construct seating furniture. The use of patterns, structural shortcuts, and piecework purchased from turners, carvers, and other specialists gave the city’s merchants, upholsterers, and entrepreneurs a financial edge over their competitors in other ports. Early in his career, Fitch’s apprentice Samuel Grant (1705–1784, fl. 1728) purchased chair frames from John Leach, James Johnson, and Edmund Perkins (1683–1781), the latter of whom bought parts from Samuel Mattocks, Jr. and Sr. These frames were upholstered either in Grant’s shop or by contractors such as Thomas Baxter. Grant’s trade network, which probably developed from the one established by his master, subsequently expanded to include chairmakers Thomas Dillaway, Samuel Ridgway, Clement Vincent, Henry and William Perkins (Edmund’s sons); joiner Daniel Ballard; and carvers Benjamin Luckie and John Welch (1711–1789).[2]

Grant also capitalized on the commercial contacts established by Fitch during the first quarter of the eighteenth century. In our recent article written with furniture historian Alan Miller, “The Very Pink of the Mode: Boston Georgian Chairs, Their Export and Their Influence,” we traced Grant’s shipments to New York and Newport and demonstrated that a large group of seating furniture formerly attributed to those cities was, in fact, made in Boston between 1730 and 1755. Earlier scholars who were unaware of the vast network of family and commercial connections emanating from Boston had erred in assuming that a chair with a New York or Newport provenance was made there. Traditional notions about Boston seating furniture in the late baroque, or “Queen Anne,” style are similarly flawed. This essay examines the evolution and distribution of Boston chairs made from the early to mid-1720s, when late baroque stylistic features began to emerge there, to the mid-1750s, when the city’s export trade began to wane.[3]

Antecedents of Boston Seating Furniture in the Late Baroque Style

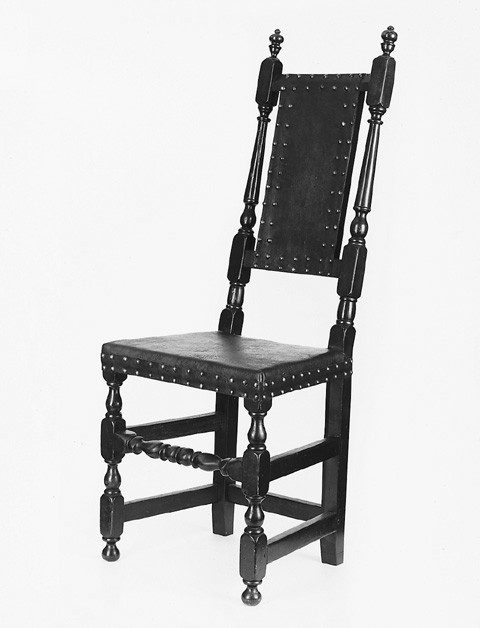

Between 1700 and 1725, the mainstay of Boston’s furniture industry was the turned and joined leather chair (fig. 1), a “provincial adaptation of the fashionable London cane chair.” Fitch’s letterbooks and ledgers record numerous shipments of leather chairs to New York, Rhode Island, and other ports in New England. In 1706, he wrote Faneuil, “I would have sent yo some chairs but could scarcely comply with those I had promised to go by these sloops.” The leather chairs exported by Fitch and his competitors were generally described as being “plain top’d” or “carv’d top.” On July 11, 1709, Fitch noted that he had sold “many of that sort to Yorkers . . . I make six plain to one carv’d; and can’t make the plain so fast as they are bespoke.”[4]

Although turned and joined leather chairs remained popular throughout the 1720s, Fitch began making examples with crooked backs and molded stiles by 1722/23 (fig. 2). These new designs were probably inspired by imported and locally made cane chairs and upholstered chairs. On October 6, 1725, Fitch wrote his London factor, Silas Hooper:

Cary. Litherhed bot for Mr. H[enr]y Deering Some frames, the fore feet of the same fashion [at 13s as] those Charg’d [me] at 21[s of which] 14 have but 37 holes and part of them not Walnutt but only culler’d over, so that the maker ought . . . to make you a further considerable allowance [the chairs] being so much over Charg’d.

Determining precisely when crooked backs and molded stiles first appeared on Boston chairs is complicated by the absence of documented examples and by the fact that Fitch’s ledger entries do not begin until 1719 and his correspondence from the winter of 1717 to the spring of 1724 is missing. As furniture historian Benno Forman has suggested, a small group of Boston cane chairs with straight backs, molded stiles, and either turned legs or sawn cabriole legs may predate their leather counterparts by about five years. If so, the late baroque style probably emerged in Boston by the early-to-mid-1720s rather than circa 1730 as previously thought.[5]

The side chairs illustrated in figures 3 and 4 are part of a group of at least thirty related examples, several of which have the capital letter “I” punched on their rear stiles or seat rails. Structural and stylistic variations among the chairs in this group indicate that their components were made by several different turners and carvers. In 1724, Samuel Mattocks, Sr. and Jr., sued chairmaker Edmund Perkins for debt, which suggests that they had furnished him with turned components or other piecework. The Mattocks, in turn, commissioned John Lincoln for carving. Such interdependence makes it difficult to determine if the chairs in this group were assembled in one shop that offered a number of stylistic variations or in several shops. The columnar side stretchers on several of these examples (fig. 3) are similar to those on a small group of Boston easy chairs that appear to date between 1710 and 1720 (see fig. 13). The chair shown in figure 3 probably falls near the end of that range. It is very similar to one that originally belonged to Reverend Daniel Perkins (b. 1697), who graduated from Harvard College in 1717. In 1721, he married Ann Foster of Charlestown and became the minister of Bridgewater.[6]

Two side chairs from the aforementioned group (fig. 4) have sawn and beaded cabriole legs, a late baroque detail presumably introduced by British imports (fig. 5) or by immigrant tradesmen such as John Jackson. London furniture makers such as Thomas Phill and Thomas and Richard Roberts began making chairs with sawn cabriole legs about 1715. Samuel Grant’s ledgers contain the earliest documentary reference to cabriole legs in Boston. On November 31, 1730, he charged Nathaniel Green £2.12 for “1 couch frame horsebone foot.” In eighteenth-century shop parlance, the term “foot” often referred to leg. The chairmakers in Grant’s network undoubtedly made frames with cabriole legs before 1730. On October 14, 1729, he sold New York merchant and ship captain Arnout Schermerhorn “1 Chair of red Chainy” and “1 do New fashion round seat.” The earliest Boston chairs with “round” or compass seats probably had turned cabriole legs and pad feet, although the latter features are not described in Grant’s accounts until January 13, 1731/32, when he billed Messrs. Clark and Kilby £12 for “6 Leathr Chairs . . . horbone round foot & cush Seats.” Considering the fact that turned cabriole legs and pad feet are stylistically later than sawn cabriole legs, it is logical to assume that the chair illustrated in figure 4 dates from the early to mid-1720s. Some of the “new fashion’d chairs” sold by Fitch during this period probably had sawn cabriole legs as well as “crook’d” backs with leather upholstery.[7]

Transitional Seating Forms with Late Baroque Details

Boston seating furniture in the late baroque style can be divided into three categories: transitional forms made during the 1720s, avante-garde forms made between 1725 and 1740, and standardized forms made from the early 1730s to the mid-1760s. On the transitional examples (see figs. 4, 6), “new fashioned” details such as cabriole legs occur in conjunction with mid-baroque, or “William and Mary,” features such as straight molded stiles and carved Spanish feet. In American Seating Furniture, 1630–1730, Benno Forman noted that the side chair shown in figure 6 was “basically a stiff-back cane chair of the Boston school—molded stiles, great heels, Spanish front feet, stretchers, double ogee apron (now integrated into the seat rail)—with overtones of the crest rail and rectilinear seat of the leather chair, onto which have been grafted elements of the ‘newest fashion,’ carved horsebone legs, . . . banister splat, and cushion seat.” Although Forman was correct in his assessment of these disparate details, the chair probably dates about 1725 rather than circa 1730 as he thought.[8]

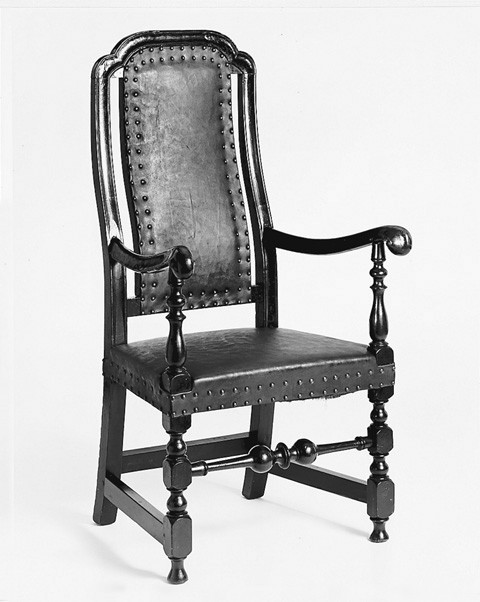

A backstool and a side chair from the same shop are among the most fully developed transitional forms (figs. 7, 8). Both have over-the-rail upholstery, sawn and beaded cabriole legs, side stretchers with elongated rear balusters and compressed front ones, and center stretchers of essentially the same pattern—extremely attenuated balusters and deep scotias flanking a sharp torus molding—like those on many Boston cane chairs and leather chairs from the 1710s and early 1720s (fig. 9). The scrolled crest rail on the backstool is similar to those on Boston easy chairs made during the first quarter of the eighteenth century (fig. 13), whereas the crest rail, molded stiles, and stay rail on the side chair are related to those on a large group of Boston leather chairs (see figs. 2, 9). The simple, crooked banister, or “India back,” of the side chair is an extremely sophisticated detail that may have been derived from imported London chairs (fig. 10). On May 31, 1718, London upholsterer George Remey sold “24 fine wallnuttree chairs wth turned feet, India Backs & India feet.”[9]

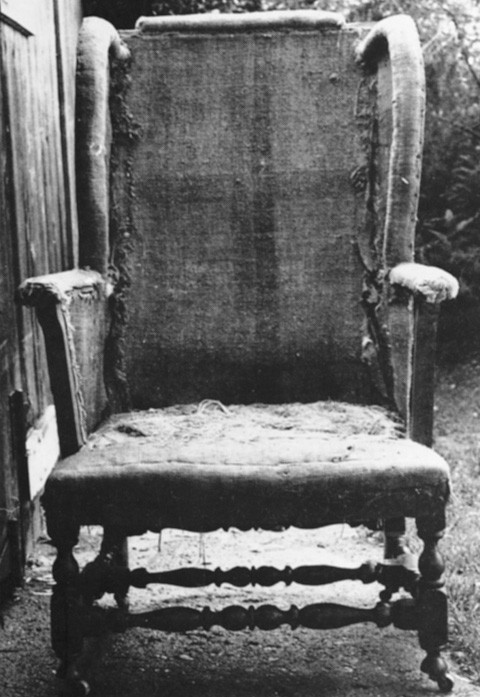

A small group of Boston easy chairs supports the date range assigned to the aforementioned backstool and side chair. Easy chairs do not appear in Boston inventories prior to 1712, but they were undoubtedly made there earlier in the century. A remarkable example formerly in the collection of Roger Bacon has a small, squarish seat and straight arms with vertical supports (fig. 11), details that occur on London easy chairs made during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Based on these features, Forman dated the Bacon example to 1695–1705. The stretchers connecting the front legs, the side stretchers, and the rear legs support his conclusions. Their distinctive turning sequences are repeated on a late seventeenth-century Boston “Cromwellian chair” (fig. 12) and on what Roger Gonzales and Daniel Putnam Brown, Jr., have termed “first generation” leather chairs. Their research strongly suggests that “first generation” leather chairs passed out of fashion in Boston about 1710.[10]

The easy chair illustrated in figure 13 is one of four with center stretchers similar to those on the Bacon chair. Like many Boston cane chairs, it has symmetrical, columnar side stretchers, an ogee-shaped front rail, and carved Spanish feet. Several easy chairs related to this example survive. Most have chamfered heels, double-scrolled arms, slightly flared cheeks, and relatively low-arched crests. The “new fashioned” chair shown in figure 14 has a rear stretcher similar to the front one on a Boston low chair made between 1710 and 1720. This stretcher design also appears on a “crook’d back” side chair with virtually identical cabriole legs and Spanish feet (fig. 6) and on numerous leather chairs made during the first quarter of the eighteenth century (see figs. 2, 9). Similarly, the side stretchers on the easy chair are closely related to those on the backstool and side chair shown in figures 7 and 8. Collectively, these chairs suggest that Boston artisans developed a relatively standardized design for easy chair frames by 1715 and that they began incorporating late baroque details by the early to mid-1720s.[11]

The Avante-Garde in Boston Seating Furniture

In 1735, John Oldmixon (1673–1742) noted that “a gentleman from London would almost think himself at home in Boston when he observes . . . their houses, their furniture, their tables [and] their dress.” Given Boston’s extensive trade with Britain and the city’s preeminent position as “the first city of New England, and of all North America,” the notion that it took the late baroque style over a decade to travel from London to Boston is implausible. Relying too heavily on the ledgers, account books, and correspondence of Fitch and Grant, scholars have overlooked the fact that furniture makers in much smaller colonial towns and cities began producing late baroque forms during the 1720s. Because Grant purchased most of his frames from other artisans, it is unlikely that he was the first to embrace the “new fashion.” Grant, moreover, may have sold chairs with “round seat[s]” and “horsebone feet” years before he began using those terms to describe seating made primarily for the middle market and for export. Boston chairmakers invariably introduced new details in objects made for the local elite. Once accepted, those details became standardized and incorporated into forms that could be mass produced and marketed to a broader clientele.[12]

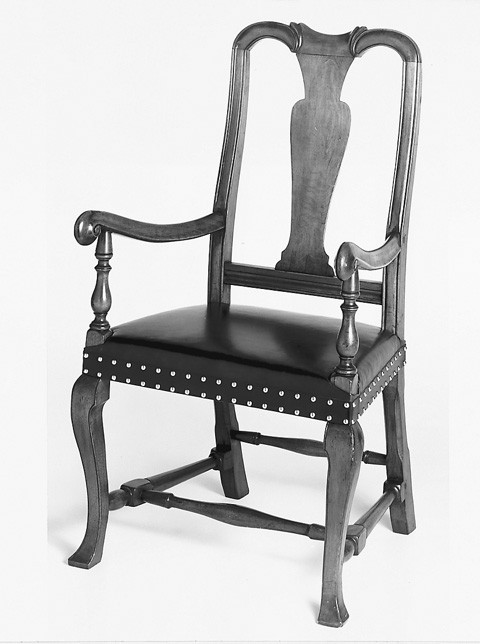

During the mid- to late 1720s, Boston chairmakers abandoned sawn cabriole legs in favor of more stylish “horsebone round feet.” Two armchairs and a closely related side chair (figs. 15-17) suggest how this process took place. Both armchairs have carved yolk crest rails, molded stiles and stay rails, vasiform splats, and bold scrolled arms with turned, baluster-shaped supports. Although they are approximately the same date and possibly from the same shop, one has sawn cabriole legs whereas the other has “horsebone round feet” and applied bosses rather than knee blocks—a feature occasionally found on British seating from the mid- to late 1720s. The side chair shown in figure 17 also had bosses (the current ones are replacements), but its curvilinear back, rounded stiles, and a delicate vasiform splat distinguish it from the two armchairs. Several technological shifts occurred with the introduction of these late baroque details. During the early 1720s, for example, Boston chairmakers began using spokeshaves to simulate turned elements, as the rear stiles and cylindrical passages on the back legs of the side chair reveal.[13]

Immigrant artisans and imported furniture were undoubtedly the source for many details found on Boston seating in the late baroque style. Boston cabinetmaker William Price (1684–1771) reportedly made “recurring visits” to England and employed at least one London journeyman. In 1726, he advertised “All Sorts of Looking-Glasses of the Newest Fashion & Japan Work, viz. Chests of Drawers, Corner Cupboards, Large and Small Tea Tables &c. done after the best manner by one late from London.” Thomas Fitch imported British chairs and textiles and corresponded with London upholsterers. On several occasions he instructed John East to send the “newest fashion’d” valence and headcloth patterns. Customhouse clearances published in the Boston News-Letter and Boston Gazette document the arrival of 122 ships from London between 1725 and 1729. This intercourse led one petitioner to complain, “the abundance of European goods sent over . . . exposes the inhabitants to appear in extravagant garbs who would gladly avoid the same, were they to receive money in lieu of their labor, manufactures and trade.”[14]

Two elbow chairs (fig. 18) with a history of ownership by Newport merchant Abraham Redwood II (1709–1788) have hooped arms and upholstered, lobed backs that are based on British seating from the 1720s and stretcher turnings that relate to those on Boston cane chairs (see fig. 4). Despite these early antecedents, furniture historians have dated the Redwood chairs as late as 1745–1765. Some scholars assumed that the chair depicted in Samuel King’s portrait of Redwood was one of the “two roundabouts” that the merchant purchased through his Boston agent Stephen Greenleaf in 1749 (fig. 19). If the roundabouts had hooped arms, then the reasoning was that the elbow chairs were contemporary with them. As Nancy Goyne Evans has shown, however, hooped arms are incompatible with the structure of roundabout chairs, so the chair depicted in the portrait may actually be one of the elbow examples. Redwood’s absence from Newport during a stay in Antigua between 1737 and 1741 has also been cited as evidence that the chair dates no earlier than the mid-1740s; however, it is far more likely that Redwood either inherited the elbow chairs from his father, Abraham (who settled in Newport in 1712), or purchased them about 1730. Although one scholar has suggested that the chairs’ mahogany primary wood supports the notion that Redwood purchased them after returning from the Carribean, Boston joiners and turners made a substantial quantity of mahogany furniture during the second quarter of the eighteenth century.[15]

The Boston armchair and side chair shown in figures 20 and 21 are based on English prototypes (fig. 22) influenced by Ming Dynasty seating. Both have India backs, hooped stiles, chamfered rear legs and heels, and cabriole front legs with turned pad feet and flat stretchers. Chairs with hooped stiles and veneered splats with marquetry (usually cyphers, arabesques, or floral designs) were popular in London from about 1715–1725. The backs of the Boston examples are black walnut veneered on soft maple, the core wood preferred by that city’s chairmakers. Their center panels are book-matched and outlined by triple-line stringing and crossbanding, but differences in the figure of the veneer suggest that the chairs are from different sets. They are, however, from the same shop. The armchair almost certainly had a center stretcher and seat rail brackets like those of the side chair. Not only is the carving on the chairs by the same hand (figs. 23, 24), but the leaves on the knees are related to those on the two original finials and appliqué of an early Boston desk-and-bookcase in the Palladian taste (figs. 25, 26). The carving on the desk-and-bookcase is similar to work attributed to John Welch (fl. 1732–1780), one of the most prolific carvers in eighteenth-century Boston, but it appears to be a generation earlier. Welch probably apprenticed with Boston carver George Robinson (1680–1737), whose granddaughter he married in 1735.[16]

The armchair (fig. 20) reputedly belonged to John (b. 1758) and Sarah (May) Holland (b. 1772) of Boston; however, their birth dates indicate that they were not the original owners. Another armchair (in the Henry Ford Museum) that appears to be from the same set has an oral tradition of ownership by a “Captain Johnson who lived in Salem . . . and moored his . . . ship in Boston harbor.” Despite these Boston area associations, scholars have traditionally attributed both armchairs and the side chair to Newport. Much of the confusion regarding other Boston chairs in the late baroque style stems from similar misattributions.[17]

The side chair illustrated in figure 27 may be from the same shop as the other examples with hooped stiles and India backs, but its sinuous cabriole legs, deeply carved C scrolls, and relatively flat pad feet are similar to those on a large group of easy chairs, backstools, and side chairs made in Boston during the late 1720s and 1730s. The earliest chairs in the group (figs. 28, 29) have side stretchers with bold baluster turnings like those on transitional seating forms from the early to mid-1720s (see figs. 7, 8, 14). The easy chair illustrated in figure 28 also has a medial stretcher similar to those on many Boston leather chairs (see fig. 9) and tight, double-scrolled arms like the examples shown in figures 13 and 14. These features suggest that the easy chair dates to about 1730, when “new fashion’d round seat[s]” and “horsebone round feet” first entered the mainstream of Boston chair production.[18]

A closely related side chair (fig. 29) supports the date assigned to the easy chair and other seating furniture in the group. Not only does the side chair share features with the example with applied bosses (see fig. 17) but its crest rail and “banister” are variants of one depicted in John Smibert’s 1732 portrait of Mary (Fitch) Oliver (1706–1732) and her son Andrew, Jr. (b. 1731) (fig. 30). Mary was the daughter of upholsterer Thomas Fitch. References to her husband, Andrew, and Smibert appear in Fitch’s accounts, although not for the purchase of chairs. Smibert completed the Oliver portrait in June 1732, nearly seven months after Samuel Grant began using the term “banister” to describe chair splats. On December 17, 1731, Grant sold export merchants Jacob and John Wendell “10 Leath Chairs @ 26/6 . . . £13.5,” and “2 Elbow do: Banist Backes 48/ . . . £4.16.” A more accurate description of the chair in Mary Oliver’s portrait can be found in Grant’s April 29, 1732, invoice to “Jno Breck Cooper at north End” for “8 Leathr Chairs horsebone feet & Banist backs . . . £10.12.” The tradesmen in Grant’s network undoubtedly made chairs with banisters before 1732, however. The side chair shown in figure 29 does not have a history, but an example from the same shop descended in a Boston family.[19]

Samuel Grant began selling backstools, or “low chairs,” with cabriole legs by 1731/32. In February of that year, he billed Clark & Kilby for “1 Crimson Chainy Easie Ch: . . . £9.18” and “1 Low chair horse bone foot cushn Seat. . . £2.17.” Although considerably more expensive than side chairs, backstools became popular in Boston during the late 1720s. John Smibert’s study for The Bermuda Group, commissioned in the summer of 1728, shows John Wainwright seated on a backstool with cabriole front and rear legs (fig. 31). Sir Robert Walpole’s accounts for furnishings at Houghton show how quickly London fashions made their way to Boston. In 1728, he ordered “12 fine wallnuttree Chair frames stuff’d back and seats, . . . a wallnuttree settee frame,” and two large “walnuttree Couch frame[s]” from London joiner Thomas Roberts. These “fine wallnuttree Chair frames” (fig. 32) are only slightly more ornate than the backstool depicted in Smibert’s painting and three contemporary Boston examples (fig. 33).[20]

As Grant’s and Walpole’s accounts reveal, backstools often accompanied other upholstered forms. Although possibly made a decade apart, the Boston backstool and easy chair illustrated in figures 33 and 34 give the impression of being en suite. Both have compass seats, cabriole legs with C scrolls and pad feet, turned rear stretchers, and flat side stretchers with cove-molded edges. Samuel Grant first mentioned flat stretchers in a February 3, 1741/42, bill to Benjamin Dolbear for “2 Chairs false Seats Flat Strechers . . . £6,” but Boston chairmakers undoubtedly made them much earlier. The medial stretcher on the easy chair is replaced, but it probably resembled the carved one on the backstool (see fig. 33) or was cove-molded like those on the side chair and easy chair shown in figures 36 and 38. Similar stretchers occur on many English and Irish chairs of the period. The construction of the backstool and easy chair also suggest that they are from the same shop. Both have flat seat rails with lap-joints at the front corners. Each joint is pierced by a quarter-round tenon cut from the upper leg stock and reinforced with wooden pins (pegs) (fig. 35). This structural detail also occurs on more conventional Boston seating forms such as the easy chair shown in figure 50.[21]

During the mid-1730s, wealthy Bostonians began responding to new stylistic impulses emanating from London. A renowned set of side chairs commissioned by merchant Charles Apthorp about 1735 (fig. 36) has broad, baluster-shaped splats with vibrant walnut veneers, angular “crook’d” stiles, cabriole front legs with claw-and-ball feet, tapered rear legs with small, squarish feet, and shell-carved crests and knees—features associated with urban British chairs made during the reign of George II (fig. 37). The Apthorp chairs and a closely related easy chair (fig. 38) may be from the same shop as the backstool and easy chair shown in figures 33 and 34. All of these chairs have classic Boston “arrow-shaped” rear stretchers and cove-molded flat stretchers. The front legs of the easy chair shown in figure 38 are attached with large dovetails that are exposed on the front and wedged rather than with quarter-round tenons, but such variations were relatively common in large shops that employed journeyman laborers and commissioned piecework from other tradesmen.

The carving on the Apthorp chairs and easy chair is attributed to John Welch. All of these examples have embryonic claw-and-ball feet that are similar to those on London seating from the early 1730s (figs. 36–38). In laying out the feet, Welch positioned the ball off center, toward the front corner of his stock, rather than centering the ball to fully utilize the dimensions of his material. By the early 1740s, he began using the more conventional, centered approach.[22]

Samuel Grant had business dealings with Apthorp as early as 1736, when the upholsterer credited the merchant’s account with “2 doz. chairs” valued at £36, “2 Elbow ditto” valued at £10.16, a “Couch Frame & Squab” valued at £7.7.9, and “Canvas & packing” valued at £1.5. The references to canvas and packing suggest that the seating was for export. Between 1738 and 1748, Apthorp received over 300 chairs from Grant.[23]

By the end of the 1730s, chairs like Apthorp’s were the avante-garde in Boston seating furniture; however, the city’s chairmakers continued to produce examples with rounded stiles, slender vasiform splats, and pad feet well into the third quarter of the eighteenth century. Much of this later seating was standardized in the sense of being produced quickly (and often rather coarsely) and in large quantities. The level of production is suggested by Grant’s payments to Edmund Perkins during the 1740s: £695.5.2 for unspecified work in 1742, £694.12.7 for “chair frames etc.” in 1745/46, and £790.18.6 for “chair frames etc.” in 1746/47. The use of piecework increased production and gave patrons a wide range of features from which to pick and choose. During the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, turners, joiners, and carvers provided a variety of components for chairmakers. This practice persisted and expanded later in the eighteenth century as other specialists became involved in the production process. When fire swept through Boston in 1760, chairmaker John Perkins lost “220 wallnot Feet for Chairs,” whereas his competitor, Joseph Putnam, lost “ 350 wallnot feet.” Mass production did not eliminate variety, however, for many standardized late baroque forms made from the late 1730s to past midcentury display creative combinations of British and Anglo-Boston details.[24]

Standardized Seating for Local Consumption and Export

In his study of the shoemaking business in colonial and federal America, economic historian John R. Commons asserted that new markets determined craftsmen’s “forms of organization.” The three levels of production that he identified have precise parallels in Boston’s chairmaking industry: custom-made or “bespoke” work for an immediate local market; standardized work, which required increased output and was geared to a broader retail market; and “order” work, which focused on standardized products made in vast quantity and sold at wholesale prices to outside markets. As the accounts of Fitch and Grant suggest, most of the seating furniture made in Boston during the first half of the eighteenth century conformed to Commons’s last two levels of production.[25]

Standardized side chairs similar to those shown in figures 39 and 40 were produced in Boston from about 1730 until past midcentury. Materials, structural options, and decorative details determined the price. The least expensive chairs, many of which represented “order work” made for outside markets, were made of maple and painted or stained to resemble a more expensive wood such as mahogany. These chairs typically had trapezoidal frames, loose seats, chamfered rear legs and heels, turned cabriole legs with pad feet, turned stretchers, flat stiles, vasiform splats, and yolk-shaped crests. Imported woods, rounded stiles, compass seats, carving, and over-the-rail upholstery increased the price, usually in proportion to material and labor costs. Grant’s accounts during the early 1730s suggest that the average price of a basic walnut chair like the one illustrated in figure 39 was approximately 26s. On September 8, 1732, Grant charged Jonathan Fayerweather for “6 Leath Chairs ban. back 26/6 . . . £7.19,” “6 Maple Chairs cushn Seats of green cha 37/ . . . £11.2,” and “8 Black Walnutt chairs cushns of Leath. . . £12.” A comparable chair with a compass seat and over-the-rail upholstery probably cost a few shillings more (fig. 40).[26]

A side chair that reportedly belonged to William Ellery, Jr. (1727–1820), of Newport (fig. 41) and another that descended in the Moses Brown family of Providence (fig. 42) are more expensive variants of standardized Boston trapezoidal and compass seat forms. Ellery’s chair may have been a bequest from his parents, William (1701–1764) and Elizabeth (Almy) (d. 1783). Like many Newport merchants, William, Sr., conducted a good deal of business in Boston. On November 23, 1745, his sloop Phoenix left Boston for Maryland with a cargo that included “1 Desk & 2 Tables” and “2 doz. chairs.” Although the rounded stiles and ogee-shaped front rail of the Ellery chair distinguish it from the most basic of the standardized side chair forms, it would have been substantially less expensive than the example illustrated in figure 42. Chairs with carved shells, curved rails, and slip seats were probably more costly than comparable forms with over-the-rail upholstery, assuming that the same textiles were used. The Brown chair probably dates from the early to mid-1740s, as does the claw-and-ball foot example shown in figure 43. By that time, Boston merchant-upholsterers like Grant were exporting standardized versions of Georgian seating along with late baroque forms. As the Ellery chair and shipping records reveal, Newporters purchased large quantites of Boston seating for both personal use and resale.[27]

Standardized seating clearly included more than just plain “order work.” The relatively coarse construction of the side chair illustrated in figure 44 marks it as a standardized form: The front rail was hastily sawn and undercut, and the flats on either side of the center drop are not parallel; saw kerfs from the shaping process are visible on the face of the front rail, inside edges of the stretchers, and around the scroll volutes on the front legs; prominent spokeshave marks remain on the rear legs; and the leg-stretcher joints are poorly finished. Despite these features, the chair is a very fashionable example of Boston seating. Its crest rail, crooked stiles, broad vasiform splat, and lambrequin-carved knees are quite similar to those on side chairs attributed to London joiner Giles Grendy (1693–1780). In addition to working for prominent Britons such as Richard Hoare and Sir Jacob de Bouverie, Grendy produced large quantities of furniture for export. A magnificent bombé bureau with cabinet that belonged to Boston merchant Charles Apthorp may be from his shop. Apthorp probably purchased the cabinet between 1735 and 1745, which would make it roughly contemporary with the Boston chair (fig. 44). Chairs exported by Grendy or one of his contemporaries may have influenced the basic design of the Boston example.[28]

A pair of side chairs that descended in the Bromfield family of Boston (fig. 45) and a set from the Huse family of Greenland, New Hampshire (fig. 46), display other options that were available in standardized formats. The Bromfield chairs share details with the preceding example—compass seats, carved rear feet, front legs with lambrequins and C scrolls—but they have different backs, stretchers with rounded outer edges, and carved slipper feet. The crests of the Bromfield chairs look back to the hooped forms that were popular in Boston during the late 1720s and early 1730s (see figs. 20, 21, 27). Multigenerational shop traditions, such as those established by members of the Perkins family, probably account for the longevity of certain styles and patterns as much as the conservatism of some of their patrons. Rounded stiles, yolk shaped crests, and slender vasiform splats were fashionable from the late 1720s to about 1750. John Singleton Copley’s portrait of Bostonian John Barrett (fig. 47) painted in 1758 shows a chair with lambrequin knees and carved C scrolls similar to the ones on the Huse chairs and the Boston examples shown in figures 44 and 48.[29]

Most of the easy chairs produced in Boston during the second and third decades of the eighteenth century were standardized forms. Between 1739 and 1747 alone, Grant sold at least fifty-four easy chairs. Many were purchased by ship captains or sold with packing materials indicating that they had been earmarked as venture cargo. On August 15, 1759, Grant billed Boston shopkeeper John Scollay £4.18.6 for “a Green [worsted] Easie Char & packing” (fig. 49). The following day, Scollay sold the chair to Jonathan Sayward of York, Maine, for the same price, which suggests that Scollay was acting as an agent for Grant. Grant’s ledger entries indicate that Clement Vincent and George Bright furnished most of his easy chair frames in 1759. Vincent typically received about 14s. per frame while Bright received approximately 16s.[30]

Sayward’s easy chair is typical of most Boston examples made from about 1730 through the 1770s. It has rear stiles that extend to form the legs (maple stained to match the walnut front legs and stretchers), slightly flared cheeks, vertical arm scrolls, turned stretchers, and cabriole front legs that are dovetailed to the seat rail. The Boston easy chair shown in figure 50 is similar, but its front legs have quarter-round through-tenons and its double-scrolled arms recall those on earlier forms (see figs. 13, 14, 28). Different shops clearly developed different production methods; however, standardization, the use of piecework components, and specialized labor were the determining factors in the evolution of the Boston easy chair.

Although a variety of design options such as leg form, stretcher shape, and ornamental carving were available in Boston easy chairs, the upholstery was invariably the most expensive component. On December 8, 1729, Grant billed Nathaniel Green for:

| 1 Easie chair fraim | 2.0.0 |

| 6 1/2 Yd. chainy @ 6.8 | 2.13.4 |

| 1 Yd 1/8 print 4 | 0.4.6 |

| 18 Yd. silk bindg. 12 | 0.16.6 |

| Tax 5 girtweb Thred & line 3 | 0.8.0 |

| 4 lb. curld hair 10 4 lb. feathers. 14 | 1.8.0 |

| 1 1/2 Yd Ticken 9.4 crocus & Ozna: 12 | 1.1.4 |

| makg: a Easie chair | 1.15.0 |

| Total | 10.6.8 |

Next to couches and settees, easy chairs were the most costly seating forms. As Grant’s bill reveals, the upholsterer’s materials and labor generally accounted for at least two thirds of the cost of an easy chair. Most of the easy chairs mentioned in Grant’s accounts between 1728 and 1732 were covered in cheney, a coarse-grained or ribbed worsted. Harateen, another relatively coarse worsted, became increasingly popular after 1738, although it had been used in Boston since the mid-1720s. On March 26, 1726, Thomas Fitch wrote Madame Anna Hooglant of New York:

I concluded it would be difficult to get Such a Calliminco as you propos’d to cover the Easie Chair, and haveing a very Strong thick Harratine which is vastly more fashionable and handsome than Calliminco I have sent you an Ease Chair Cover’d wth sd Harrateen wch I hope will Sute you.

Fitch and Grant understood the importance of satisfying their clients’ desires for the latest London fashions and accommodating regional tastes. In December 1731, Fitch instructed London upholsterer John East to send “a pattern or figure of [a] Fashionable Vallance & the figure of a headboard & headcloth. . . . he may send some with a little more work, our people too generally choosing them somewhat showy.”[31]

Whether for bedsteads or easy chairs, fashionable textiles gave Boston consumers the opportunity to distinguish their furniture from that of their peers. Grant’s records reveal that his clients occasionally replaced or updated upholstery. On October 26, 1756, he billed John Scollay for “new covd easie chair & 2 window squabs.” Several Boston easy chairs retain their original upholstery, but few are as elaborate as the one shown in figure 51. The front of this chair is covered with Irish-stitch needlework, and the back panel is embroidered with a rural landscape. The crest rail is inscribed “Gardner Junr/ Newport May/ 1758/ W.” Such inscriptions usually identify either the owner or upholsterer. The one on this chair may refer to Caleb Gardner, who died in Newport in 1761. His son, Caleb, was born in 1750 and did upholstery work for Abraham Redwood in 1774. Although the Gardner chair has been attributed to Newport, its stretcher turnings, integral rear stiles and legs, and basic frame design have parallels in the Sayward chair and many other examples with Boston-area histories. Evidence suggests that both the frame and landscape panel of the Gardner chair were shipped from Boston to Newport. Textile historian Amelia Peck has attributed the panel to an anonymous Boston needlework school, based on its composition and stitching.[32]

Distribution and Misattribution

Given the Rhode Island provenances of many Boston chairs, it is understandable that scholars attributed some of them to Newport tradesmen. Much of the confusion can be traced to a set of six side chairs and an easy chair that descended in the Eddy family of Warren, Rhode Island (figs. 52, 53). These objects have been erroneously associated with Job Townsend (1699–1765) ever since they appeared in the Philip Flayderman sale at Anderson Galleries in 1930. Although the sale catalogue failed to provide documentation for the attribution, when the chairs sold again in 1932 they were described as part of a group of furniture “made by Job Townsend for the Eddy family of Rhode Island in 1743. One of these pieces, which bears Townsend’s label, still remains in the possession of this family.” The fact that the Eddy family may have owned a piece labeled by Townsend does not mean that the chairs came from the same source. Judging from Townsend’s surviving account books, which span the years 1751–1757, the principal output of his shop was case furniture and tables. No chairs are listed during that period.[33]

The hooped crests, flat stretchers, and carved C scrolls on the Eddy chairs clearly establish their Boston origin. Based on their relationship to the earlier “India back” arm chairs and side chairs shown in figures 20, 21, and 27 and later standardized examples with flat stretchers (see fig. 44), the Eddy chairs appear to date from the 1740s. A ship captain named Jeremiah Eddy transported a large number of Boston chairs to Rhode Island during that decade, so it is conceivable that these chairs or other Boston examples descended in a branch of his family. Harbor clearances listed in the Boston News-Letter indicate that Eddy sailed to Newport at least twenty times between January 3, 1739, and December 27, 1744. Eddy was a native of Swansea, Massachusetts, which bordered Warren, Rhode Island (incorporated on January 27, 1746/47).[34]

Since the 1930s, furniture historians have used the design vocabulary of the Eddy suite to attribute numerous Boston chairs to Job Townsend and other Newport tradesmen. Similar misattributions can be traced to a set of chairs that descended in the Moses Brown family of Providence (see fig. 42). A 1927 Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design noted that the set could be the “Leather Chairs” that Brown purchased from John Goddard in 1763. The Brown chairs clearly date from the 1740s or 1750s, however. Like a set of chairs once owned by Charles Barrett, Sr., of Concord, Massachusetts (and later New Ipswich, New Hampshire), the rounded stiles and shell-carved crests of the Brown chairs take their design cue from earlier British models. Because the Townsends, Goddards, and other Rhode Island cabinetmakers used carved shells on much of their case furniture, scholars cited the shells on the crests of the Brown chairs as evidence of Rhode Island manufacture. Not only does the carving on the Brown chairs speak to a strong Boston tradition, but the shells on Newport seating from the 1760s on were derived from Boston chairs imported into Rhode Island during the second and third quarters of the eighteenth century. A Boston desk-and-bookcase with a probable history of ownership by William Cabot of Salem has a lobate shell on its scrollboard that is almost identical to the shells on the Brown set.[35]

Rhode Islanders purchased seating furniture in Boston because it was the dominant center of upholstery and chairmaking in the colonial Northeast. Between 1729 and 1739, the output of Samuel Grant’s enterprise alone amounted to 2,006 chairs, 138 stools, 49 couches, and 44 easy chairs. Between 1725 and 1730, at least 278 vessels sailed from Boston to Rhode Island. Thomas Fitch, whose primary trade was European textiles, had over thirty-two clients in Rhode Island. Boston’s command over chairmaking and upholstery is underscored by the sheer numbers of its industry. Between 1730 and 1750, eighty-eight cabinetmakers and joiners, twenty-two chairmakers, fourteen upholsterers, six carvers, five turners, six japanners, one glazier, and one chair caner worked in Boston—far more than in any other colonial city. During the same period, thirty-seven cabinetmakers and joiners and three carvers worked in Newport, but records identify only one chairmaker and no upholsterers.[36]

Rhode Island ship captains and merchants were among the principal importers of Boston seating furniture. One of the most ambitious Newport merchants of the 1730s and 1740s was John Banister (fig. 54). In a 1739 letter to John Thomlinson of London, Banister noted that Newporters desired “to make themselves Independent of the Bay Government to whom they have a mortal aversion.” Banister’s frustration stemmed from his own dependence upon Boston suppliers such as upholsterers William Downe and Samuel Grant, from whom he purchased “12 Lea: Chairs ” for £19.4 and “18 Lea Chairs” for 32s. respectively, in 1739. Banister’s account books reveal that he purchased 144 chairs in Boston between 1741 and 1743.[37]

The chairs Banister purchased represent a variety of Boston export styles. On March 31, 1743, he “bought by Mr. Hugh Vans in Boston & Shipped on board the Sloop Ann, Joseph Dean Master for Newport” two dozen chairs, including “6 Leather chairs @ 34 . . . 10.4,” “6 Lea back Red @ 34 . . . 10.4,” “6 ditto Black @ 38 . . . 11.8,” and “6 ditto Horsefoot @ 38 . . . 11.8.” Two weeks earlier he had received a cargo via “Capt. Eady” of “30 Chairs Leather Backs & Bottoms @ 38/” totaling £57 and “6 ditto Leather Bottoms @ 35/6” totaling £10.13. “Eady” was likely the aforementioned Jeremiah Eddy, whose name appears frequently in Banister’s accounts of that year. Banister also purchased work from John Welch. An invoice of July 1, 1743, indicates that Banister received “a Lyon Head . . . from Welch” valued at £35.2, which was presumably a ship’s figurehead.[38]

By the mid-1740s, Rhode Island was entering into an era of improved productivity and prosperity. Local industries were growing, and the colony’s merchants and entrepreneurs were beginning to establish regular and direct trade routes with London, Bristol, and other European ports. Before midcentury, Newport did not have the artisan base to support a chairmaking industry, but after 1755, local tradesmen like the Townsends and Goddards began making and exporting seating furniture. Jeanne Sloane estimated that fifty-six cabinetmakers were active in Newport between 1745 and 1774, compared with sixty-four in Boston—a city with a much larger population. Additional measure of Newport’s improved industry can be taken from southern port-of-entry records. Between April 6, 1756, and December 24, 1775, at least 128 ships arrived in Annapolis from Boston and at least 67 arrived from Newport. Despite Boston’s numerical dominance, the Newport cargoes had a higher percentage of case furniture, tables, and chairs. Newport vessels carried an average of nine pieces per vessel, whereas Boston ships carried an average of three. During this period, 25 case pieces, 20 tables, and 380 chairs arrived in Annapolis from Newport.[39]

In 1738, Banister traveled to London to begin developing trade alliances that would challenge Boston’s dominance in intercoastal shipping. His invoice book of 1739 describes one of his first London cargoes, which included “4 Pier glasses in neat wallnuttree Frames . . . £7.12,” “4 Ditto Carv’d edge & Shell . . . £7.12,” “3 Ditto . . . wth out gold . . . £3.18,” “a Walnuttree Card Table . . . £2.5,” “a Bewroe table wth a Desk . . . 2.10,” “8 Walnuttree Chairs w. Seats Covered with black Span: Leather . . . £9.12,” and “1 Elbow Chair . . . Ditto . . . £1.11.6.” Signaling things to come, Banister wrote his London suppliers Thomas and James Hayward on May 28, 1739:

my hurry obliges me to Proceed upon the Head of Business, which at present Looks with an Incouraging prospect the people of this Colony being resolved to Brake of their Dependence for Boston therefore have Generously purchased the Greatest part of my cargoe already.[40]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article, we thank Gavin Ashworth, Luke Beckerdite, Merrilee Posner, Allan Breed, Michael K. Brown, Amy Coes, Wendy A. Cooper, Jane Furr Davis, Linda Epich, Frank Fuller, Elisabeth D. Garrett, Constance and Dudley Godfrey, Roger Gonzales, Nicholas Grindley, Anne Rogers Haley, Clifford and Ralph Harvard, Morrison H. Heckscher, Brock Jobe, Marybeth Keene, Leslie Keno, Alan Miller, Ruth Oliver Morley, Robert Mussey, Milo Naeve, Dr. King Odell, Andrew Oliver, Jr., Daniel Oliver, Jess Pavey, Amelia Peck, Ronald Potvin, Jonathan Prown, Margaret Reasor, Betty Ring, Albert Sack, G. W. Samaha, Lesley and George Schoedinger, Nancy Shaw, Jim Tottis, Robert Trent, and Anne and Fred Vogel.

Roger Gonzales and Daniel Putnam Brown, Jr., “Boston and New York Leather Chairs: A Reappraisal,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1996), pp. 179–89. Benno M. Forman, American Seating Furniture, 1630–1730 (New York: W. W. Norton for the Winterthur Museum, 1988), pp. 244, 286, 313. Leigh Keno, Joan Barzilay Freund, and Alan Miller, “The Very Pink of the Mode: Boston Georgian Chairs, Their Export and Their Influence,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1996), p. 269. Samuel Grant’s account books and receipt book are in the following collections: Account Book, 1728–1737, Massachusetts Historical Society; Receipt Book, 1731–1740, Bostonian Society; Account Book, 1737–1760, American Antiquarian Society.

Samuel Grant Account Book, October 14, 1729; November 21, 1730; and January 13, 1731/32. Thomas Phill sold chairs with sawn cabriole legs, described as “frames of ye newest fashion,” to Edward Dryen of Canons Ashby in Northamptonshire in 1714 (see Nicholas Grindley, The Bended Back Chair [London: Barling, 1990]). One of the chairs from Canons Ashby is illustrated in Ralph Edwards, The Shorter Dictionary of English Furniture (London: Country Life), pp. 133, fig. 67. Edwards also illustrates another early cabriole leg chair made for Sir William Humphrey, Lord Mayor of London, about 1717 (ibid., p. 135, fig. 75). A suite of furniture possibly made for the Earls of Guilford, Sezincote, Gloucestershire, has carved details that suggest a date of production earlier than the Dryen and Humphrey suites (see Sotheby’s Important English Furniture, London, July 10, 1998, p. 28, lot 6). For chairs attributed to the Roberts family, see Christie’s, Works of Art from Houghton, London, December 8, 1994, lots 126 and 127. Two Boston side chairs with sawn cabriole legs not illustrated in this article are in a private collection in Newbury, Massachusetts. Both are made of maple and have a punched “I”. Forman, American Seating Furniture, p. 286. On February 27, 1722/23, Fitch sold Edmund Knight “1 doz crook’d back chairs” for £16.4. On March 20, 1723/24, Fitch sold a dozen “Rushia newest fashion’d chairs” to Adam Powell of New York (ibid., p. 285).

Boston Gazette, April 4–11, 1726. Brock Jobe, “The Boston Furniture Industry, 1720–1740,” in Boston Furniture of the Eighteenth Century, edited by Walter Muir Whitehill, Brock Jobe, and Jonathan Fairbanks (Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1974), p. 28. As quoted in Alan Miller, “Roman Gusto in New England: An Eighteenth-Century Boston Furniture Designer and His Shop,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1993), p. 162. The tally of chairs was derived from customhouse clearances posted in the Boston News-Letter and Boston Gazette. The 1735 petition is quoted in Justin Winsor, ed., The Memorial History of Boston, 1630–1880, 4 vols. (Boston: Tickner and Co., 1886), 2:457, nt. 1.

For more on the influence of Ming furniture on London seating, see Grindley, The Bended-Back Chair. The Boston desk-and-bookcase is illustrated and discussed in Miller, “Roman Gusto in New England,” pp. 167–70. For more on Welch’s apprenticeship, marriage, and career, see Mabel M. Swan, “Boston’s Carvers and Joiners, Part I,” Antiques 53, no. 3 (March 1948): 199; Myrna Kaye, “Eighteenth-Century Boston Furniture Craftsmen,” in Whitehill, Jobe, and Fairbanks, eds., Boston Furniture of the Eighteenth Century, p. 301; Barbara M. and Gerald W. R. Ward, “The Makers of Copley’s Picture Frames: A Clue,” Old Time New England 67 (summer-fall 1976): 16–20; Luke Beckerdite, “Carving Practices in Eighteenth-Century Boston,” in New England Furniture: Essays in Memory of Benno Forman, edited by Brock Jobe (Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1987), pp. 123–62; Morrison H. Heckscher, “Copley’s Picture Frames,” in Carrie Rebora, Paul Staiti, et al., John Singleton Copley in America (New York: Harry Abrams for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995), pp. 142–59; and Keno, Freund, and Miller, “The Very Pink of the Mode.” Evidently, Robinson was very successful. His inventory included shop goods valued at £139.19.8 and a silver plate worth £58.10.1 (Forman, American Seating Furniture, p. 313).

Richards and Evans, New England Furniture at Winterthur, pp. 24–26. Sarah May’s father, Samuel (b. Roxbury, February 17, 1723; d. Boston, August 9, 1794), was a Boston area carpenter. If the chair descended in his line, Samuel was probably the second owner. For more on the May family, see Rev. Samuel May, “Col. Joseph May, 1760–1841,” New England Historical Genealogical Register 27, no. 2 (April 1873): 113–15. The Johnson history was given to Michigan dealer Jess Pavey, who sold the armchair to the Henry Ford Museum (Jess Pavey to Leigh Keno and Joan Barzilay Freund, August 9, 1996).

Clifford K. Shipton and John L. Sibley, Biographical Sketches of Those Who Attended Harvard College, 17 vols. (1942; reprint ed., Boston: Harvard University Printing Office, 1962), 12: 151. Anderson Galleries, Colonial Furniture, The Superb Collection of Mr. Francis Hill Bigelow of Cambridge, Massachusetts, New York, January 17, 1924, lot. 142. William Ellery, Jr., also attended Harvard (class of 1747) and roomed with Andrew Oliver, Jr., whose mother was Mary Fitch (see fig. 30). For more on the Ellery family, see Shipton and Sibley, Biographical Sketches of Those Who Attended Harvard College, 7:66–69, 12:134–52. Keno, Freund, and Miller, “The Very Pink of the Mode.” A Boston chair similar to the example shown in figure 43 but with pad feet is illustrated in Edwin J. Hipkiss, Eighteenth-Century American Arts: The M. and M. Karolik Collection (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press for the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1941), p. 142, fig. 79.

Although no bills, labels, or account books were mentioned in the sale catalogue, the set was identified as the work of Job Townsend and “purchased in Warren, Rhode Island, from a descendant of the original owner.” Anderson Art Galleries, Philip Flayderman Collection, January 4, 1930, lots 492, 493; Anderson Galleries, One Hundred Important American Antiques, January 9, 1932, lots 80, 81, 85. The Eddy chairs are in a private collection in California. Job Townsend Account Books, Newport Historical Society. Jeanne A. Vibert, “Rhode Island—Attributed Queen Anne Chairs,” unpublished paper, University of Delaware, December 22, 1978, p. 6; and Oswaldo Rodriguez Roque, American Furniture at Chipstone (Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press for the Chipstone Foundation, 1984), p. 38, no. 17.

For example, on May 3, 1743, Eddy transported “30 Chairs Leather Back & Bottom @ 38/ [and] 6 Ditto Leather Bottoms @ 35/6” to John Banister of Newport (Banister Invoice Book, Rhode Island Historical Society). For more on Jeremiah Eddy, see Ruth Eddy, comp., The Eddy Family in America (1930; reprint ed., Ann Arbor, Mich.: Braun-Brumfield, Inc., 1990), p. 74.

Attribution of the Eddy chairs to Townsend became more entrenched following the publication of Ralph E. Carpenter, Jr.’s, The Arts and Crafts of Newport Rhode Island 1640–1820 (Newport, R.I.: The Preservation Society of Newport, 1954), p. 39, nos. 13, 17. Charles Hummel’s “Queen Anne and Chippendale Furniture in the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum” (Antiques 98, no. 6 [December 1970]: 900–9), questioned this attribution as cited by Carpenter in The Arts and Crafts of Newport and Joseph Ott in The John Brown House Loan Exhibition of Rhode Island Furniture (Providence: Rhode Island Historical Society, 1965), p. 4, no 4; however, Hummel also attributed the Eddy chairs to Rhode Island. “John Goddard and His Work,” Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design 15, no. 2 (April 1927):15. The original letters from Brown to Goddard are at the Rhode Island Historical Society. When Ralph Carpenter included a chair from the set in The Arts and Crafts of Newport, he wrote that the set was “evidently the ‘leather chairs’ referred to in a letter from Moses Brown to John Goddard” (p. 37, no. 11). Frank Fuller, archivist at the Moses Brown School, confirmed that the Moses Brown School’s attribution of the chairs to Goddard was based upon Carpenter’s research (Fuller to Keno and Freund, August 16, 1996) and not upon any evidence provided by the Brown family at the time the chairs were donated. Vibert, “Rhode Island Chairs,” p. 6. See The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Collecting American Decorative Arts and Sculpture, 1971–1991 (Boston: By the museum, 1991), p. 35, pl. 8. For more on Barrett, see Jobe and Kaye, New England Furniture, pp. 154–55.