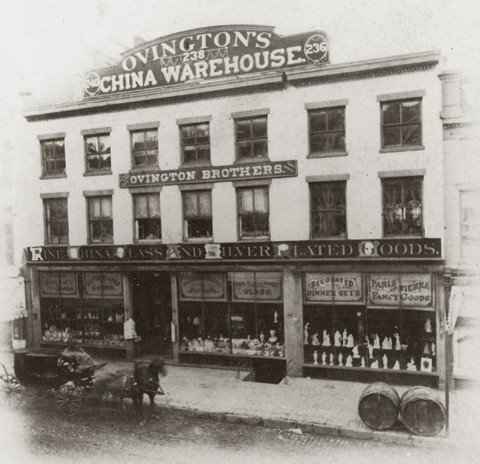

Ovington’s China Warehouse, Brooklyn, New York, ca. 1875. (Courtesy, Susan Myers.) Note the display of parian in the window at right.

The Greek Slave, Minton and Co., Staffordshire, England, 1849. Parian. H. 14 1/2". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Russell E. Burke III, 1983.)

Figure of a poodle, attributed to United States Pottery Company, Bennington, Vermont, 1849–1858. Parian. H. 8 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Jay Lewis.)

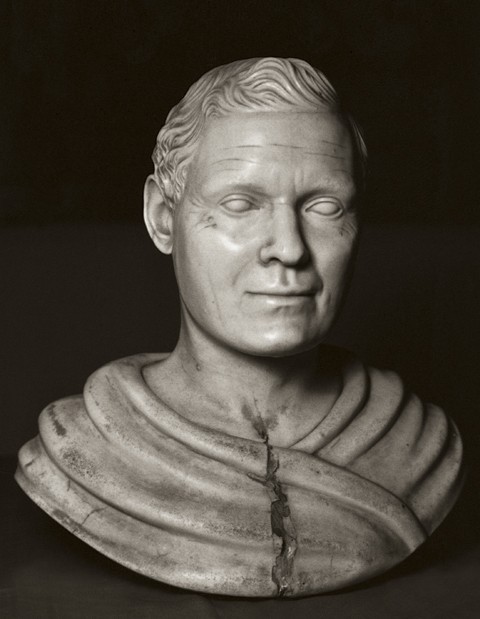

Bust of Christopher Webber Fenton, United States Pottery Company, Bennington, Vermont, ca. 1853. Parian. H. 14 9/16". (Collections of Bennington Museum, Bennington, Vermont.)

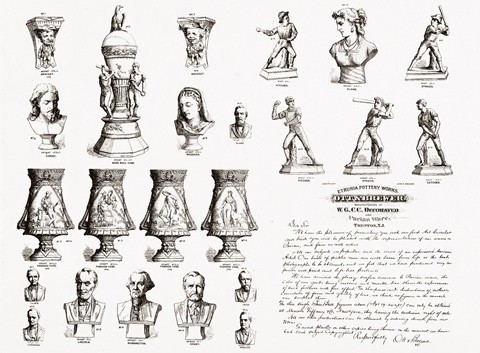

Illustration of the United States Pottery Company exhibit from Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, 1853. (Courtesy, Mr. and Mrs. J. Garrison Stradling.)

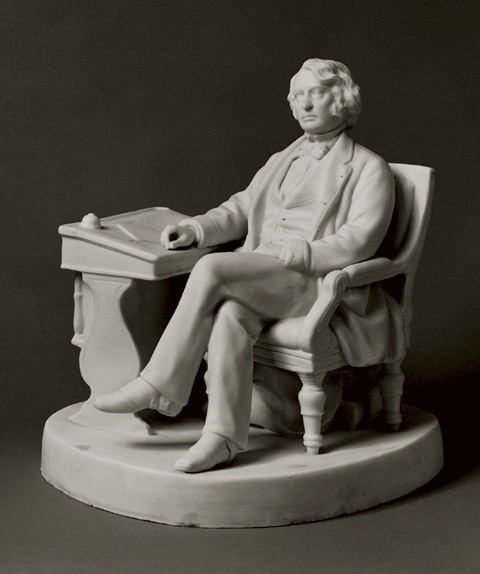

Daniel Webster, Thomas Ball, Boston, 1853. Parian. H. 25". (Courtesy, Chicago Historical Society.) www.chicagohs.org

Governor Andrew of Massachusetts, designed by Martin Milmore, published by Jones, McDuffee and Stratton, Boston 1860–1865. Parian. H. 21". (Courtesy, Mr. and Mrs. J. Garrison Stradling.)

Wounded to the Rear: One More Shot, John Rogers, New York. ca. 1864. Parian. H. 18 3/4". (Courtesy, Strong Museum, Rochester, New York © 2002.)

Joe’s Farewell: Dolly Varden and Joe Willett, Daniel Chester French, copyrighted by Clark, Plympton & Company and made by Robinson & Leadbeater, 1871–1874. Parian. H. 9 3/4". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. Charles Beekman Bull in memory of her mother, Alice Hawke Reimer, 1957.)

Young Columbus, copyright applied for H. F. Libby, Jones, McDuffee & Stratton, ca. 1878. Parian. H. 15 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Jay Lewis.)

Baseball Vase, designed and modeled by Issac Broome, Ott & Brewer, Trenton, New Jersey, 1875–1876. Parian. H. 38 3/4". (Courtesy, Detroit Historical Museum.)

Photograph of the Ott & Brewer display at the American Institute Fair, New York City, 1877. (Private collection.)

Broadside, Ott & Brewer’s Eutria Pottery Works, Trenton, New Jersey, ca. 1876. (Collection of David and Barbara Goldberg.)

Bust of Elaine, Lenox China, Trenton, New Jersey, 1914. Parian. H. 14 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Jay Lewis.) This bust, which appeared in the Ott & Brewer display illustrated in fig. 12, was designed and modeled by Issac Broome in 1876 and recast by him at Lenox in 1914.

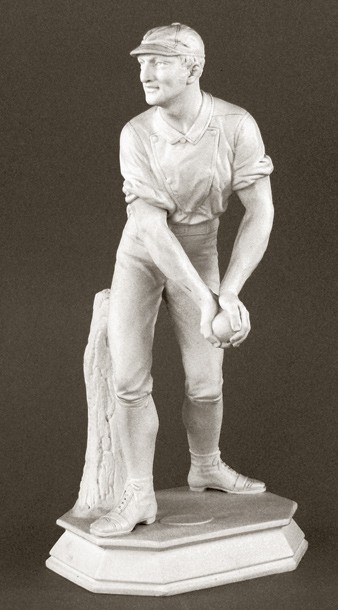

Figure of a Catcher, modeled by Issac Broome, Ott & Brewer, Trenton, New Jersey, 1875–1876. Parian. H. 14 7/8". (Private collection.)

The Blacksmith, Karl Mueller, Union Porcelain Works, Greenpoint, Brooklyn, New York, ca. 1876. Parian. H. 12". (Courtesy, Brooklyn Museum; photo, Schecter Lee.

Charles Sumner, modeled by J. D. Parry, James Carr’s New York City Pottery, 1874. Parian. H. 13". (Collection of the Newark Museum, Gift of Miss Sara Carr, 1924.)

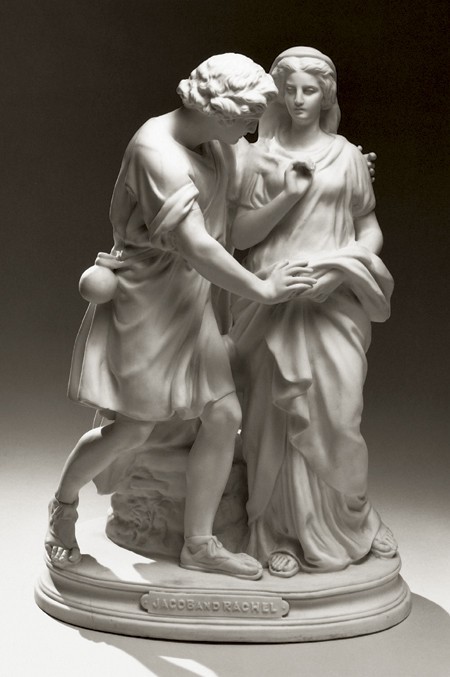

Meeting of Jacob and Rachel, modeling attributed to J. D. Parry, James Carr’s New York City Pottery, 1876. Parian. H. 22". (Collection of the Newark Museum, Gift of Miss Sara Carr, 1924.)

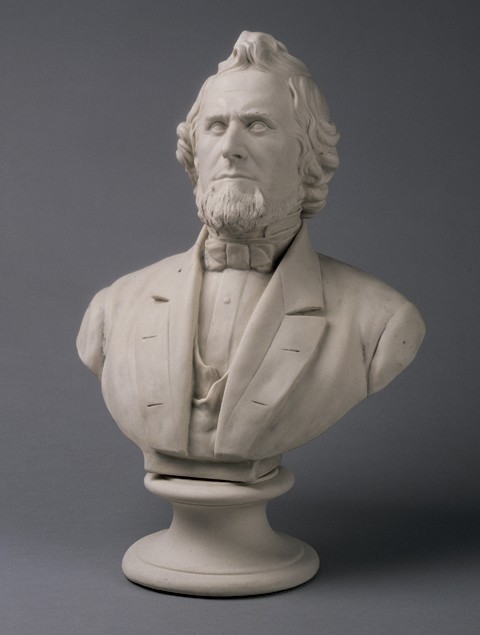

Bust of James Carr, modeled by W. H. Edge, James Carr’s New York City Pottery, ca. 1876. Parian. H. 21 3/8". (Collection of the Newark Museum, Gift of Miss M. E. Clark, 1924.)

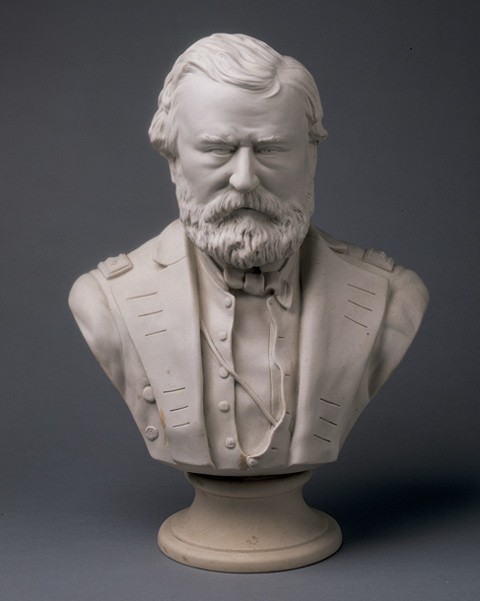

Bust of Ulysses S. Grant, designed and modeled by W. H. Edge, James Carr’s New York City Pottery, 1876. Parian. H. 18 9/16". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Purchase, Anonymous Gift, 1968; photo, Schecter Lee.)

Developed by English potters in the 1840s, parian porcelain statuary made sculpture available for the homes of the new, middle class in the same way that engravings duplicated famous paintings. The success of the infant industrial revolution in creating a more comfortable lifestyle for merchants and managers also provided these consumers with art for the home, a type of material culture previously owned only by the courtly class. Much like today, the desire for consumer goods was developed and encouraged by associating their ownership with the perception of a better life. During the nineteenth century, this life was defined as moral, educated, and enlightened. The proper Victorian family in its parlor was expected to be surrounded by trophies which showed its interest in literature, the fine arts, and travel.

The idea of making many copies of a single important work of art was well established by the time parian porcelain statuary came on the scene. Engravings of famous paintings had long been available, and any number of examples from the first half of the nineteenth century could be cited. Asher B. Durand’s engraving of Ariadne, after the painting by John Vanderlyn, came on the market in 1835. The Portland Vase is another example. The Duchess of Portland created a stir by acquiring the original ancient cameo-glass vase from the Barberini Palace in the late 1700s. Wedgwood’s stoneware copy soon followed and continued to be offered for many years into the nineteenth century in a variety of colors to coordinate with any interior. Historians call this the “commodification of art.” For the companies that made and/or marketed the goods, this might be an appropriate characterization. For those who bought the wares, however, there were deeper meanings of identity and possession. The buyer of the copy also acquired the sensation of owning the original and shared its possession with any number of family, friends, and acquaintances who recognized its significance.

Sculpture, or its full-scale reproduction, was more difficult to own than prints or pottery because of its size, weight, cost, and scarcity. The development of parian porcelain statuary in England offered a new dimension for the parlor. Named after a type of marble, the fine white, unglazed parian porcelain suitably mimicked the ancient sculptural material. Sculpture, which had been reproduced only in engravings, was now available in the round, reduced in size but retaining its form and proportion. Many conditions came together to make parian porcelain statuary successful during the mid-nineteenth century.[1] Discoveries in clay chemistry and ceramic technology in the pottery industry provided the fabric. The rise of the art union lotteries as purveyors of fine art helped to create the market. And the proliferation of art magazines encouraged, among other things, the development of English sculpture as an art form worthy of appreciation and support.

From the beginning, parian was marketed as an art material that would satisfy the tastes of the new middle class, and the English potteries produced subjects that appealed to these buyers—busts of royalty and important writers, politicians, and artists; reproductions of antique and contemporary sculpture; and, later, the sentimental Victorian subjects developed by factory modelers from popular literature and paintings.

English parian was available in America from the time of its introduction in England, and American sculptors soon took advantage of parian as a medium for promoting their skills and reaping some financial benefit from their talents (fig. 1). Eventually American manufacturers developed the materials and techniques and cultivated the artists to produce a homegrown product. Before the invention of parian ware, nearly all of the modeling for manufactured ceramics, particularly in England and America, was done by artisans trained through the apprentice system within the factories. With parian, however, ceramic manufacturers discovered the monetary rewards of attaching their production to fine art.

They also understood the benefits that could be drawn from employing artisans with a formal education in the arts. The importance of designers to the ceramic industry and the need for academies to train them began with the marriage of ceramic art and the parian industry. Although parian had largely passed from fashion by the late 1880s, its legacy in terms of the new attitudes toward art among manufacturers was only beginning to be felt in the ceramic industry. As schools of ceramic art and design increased in number and sophistication during the twentieth century, so did the impact on ceramics as one of the applied arts.

Parian’s Technique

Figurines have long been part of the potter’s repertoire, although a distinct fashion for them developed among the courtly class in the mid-eighteenth century. Important European potteries—Sevres, Meissen, Derby—made a variety of white (unglazed or biscuit) and decorated models to embellish banquet tables and palace mantels. By the early 1800s, figures in earthenware of mediocre quality were being turned out in great quantity from the Staffordshire potteries for the English middle class. But several prominent potteries such as Minton, Worcester, and Copeland & Garrett had continued to make the white biscuit figures and to search for a high-quality clay body that would resist the soiling that came from handling the unglazed surface.

At the same time, modelers and mold makers in the English industry had developed their crafts to the highest level. Although the chemistry of slip casting had been discovered in the previous century, the dynamics of modeling and mold making were greatly refined during the second quarter of the nineteenth century.

Most sculptural ceramic figures are extremely complex and cannot be accommodated by a single mold. The mold maker had to dissect the model into manageable parts that were later joined by the repairer when the slip-cast parts were in the green state. The joints between parts were carefully hidden and smoothed so that the viewer rarely noticed the number of pieces that had been combined to create the final figure.

Modelers were considered the most skilled of this group of craftsmen. Working in plaster or clay, they were required to copy an existing model so that the figure that resulted would have the proper proportions even after the fire had reduced the green clay by twelve to fifteen percent. The work of the modelers was greatly aided by Benjamin Cheverton’s reducing machine (essentially a three-dimensional pantagraph) that was patented in 1844.[2] By improving the fidelity of these statuary reproductions to the originals, Cheverton’s machine allowed parian porcelain to do for sculpture what engraving had done for painting—make facsimiles available for display, ornament, and study in the home.

Although there is still dispute over which pottery first introduced parian porcelain statuary, several English firms were making figures in this new material by 1845. Various names were used in the earliest years: “Statuary Porcelain” at Copeland & Garrett; “Parian” at Minton; and “Carrara” at Wedgwood. Both “Parian” and “Carrara” referred to the desirable marble, which the ceramic body was intended to imitate. By 1851, the term “Parian” was in general use. Formulas for the clay body itself were as numerous as were the potteries that made parian, but they all shared the basic ingredients of feldspar in concentrations of thirty to sixty-five percent, Cornish clay, and Cornish stone. Some recipes also included ball clay, flint glass, barium carbonate, or frit, but it was feldspar that gave parian its distinctive hardness, smooth surface, and pale creamy translucency.

The new material was hailed as being far more successful in duplicating the look and feel of marble than any previous biscuit body both in the way it transmitted light and in the detail possible from its fine texture. In 1851, the Illustrated London News reported that the “introduction of the comparatively new material of Parian for statuettes and ornaments generally, has given a feeling of art to those productions which the old bisque body could never have done. The rich transparent tone of the Parian, giving the reflected light and semi-opaque shadows of marble, contrasts so unmistakably with the grey looking tint and hard effect of the bisque, that no one can wonder that the latter is now completely superceded in England.”[3] English sculptor and royal academician John Gibson, the first artist to give permission for his work to be translated into parian, declared that it was “the best material, next to Marble” when he was introduced to it on a tour of the Staffordshire potteries in 1845.[4]

Marketing English Sculpture through Parian

The happy alliance of artist, manufacturer, art magazine, and art union created the commercial success of parian porcelain statuary. Gibson’s remark was made during a meeting arranged by the editor of the Art Journal that included Gibson and several other sculptors, Thomas Battam of Copeland’s staff, and agents of the Art Union of London. The meeting resulted in the production at Copeland’s of fifty copies of Gibson’s diploma work, Narcissus, for distribution as lottery prizes by the Art Union. By combining the morality of art with the suspense of a lottery, art unions satisfied both the middle-class desire for respectability and the ability to obtain it at relatively small cost.

The success of the art unions in popularizing contemporary British and European art was based largely on their ability to educate the public. The organizers recognized two types of persons who needed nurturing: “The first consists of those who, although possessed of taste are not wealthy; the other are those of ample means, but who . . . have hitherto evinced little interest in the progress of the arts and little taste for their productions.”[5] The contemplation of art, it was believed, would lift both types to a higher moral plane. “The influence of the Fine Arts in humanizing and refining, in purifying the thoughts and raising the sources of gratification in man, is so universally felt and admitted, that it is hardly necessary now to urge it,” noted the Art Union of London in 1840.[6]

In addition to patronizing the art unions, Victorian Britons were also attracted to fine art and parian through the regional, national, and international fairs held in London and other British centers, and by the attention focused on the annual academy exhibitions in England and Scotland. Much publicity in the popular and art presses was generated by the strong showings made by parian manufacturers at these exhibitions. The largest show of parian was made at the Great Exhibition, London, in 1851, where more than ten manufacturers mounted displays of the porcelain statuary.

The Greek Slave

Of all the contemporary sculpture that was reproduced in parian porcelain during this period, Hiram Powers’ Greek Slave was peerless in terms of its own fame and in the recognition that it continued to draw from its many reproductions. In 1843, Powers (1805–1873), an American sculptor, executed the first Greek Slave and six full-size marble replicas that were produced by 1866. The chained maiden, meant to symbolize the young Christian women auctioned by the Turks during the Greek revolution, was shown first in London in 1845 and subsequently appeared at several international fairs and many galleries there and in the United States. One statue toured a number of American cities between 1847 and 1852, from New York to St. Louis and Detroit to New Orleans. As a result of its widespread renown, the statue engendered innumerable reviews and a fair number of poems extolling its spirituality and chastity despite, or perhaps because of, its naked and manacled form. “The grey-headed man, the youth, the matron, and the maid alike yield themselves to the magic of its power, and gaze upon it in silent and reverential admiration,” observed a reporter for the Courier and Enquirer of the statue’s exhibition in New York City in 1847.[7]

Reproductions of the Greek Slave in plaster, parian, bronze, crude marble, and alabaster in several reduced sizes were extraordinarily popular. Writing in Godey’s Lady’s Book, Mrs. Merrifield advised that a plaster copy of the figure “should be found on the toilette of every young lady who is desirous of obtaining a knowledge of the proportions and beauties of the figure.”[8] Several British potteries made small-scale copies, but the earliest and perhaps best was Minton’s (fig. 2). Made originally for Summerly’s Art Manufacturers, a marketing firm that promoted public taste by getting well-known artists to design common objects, the Minton version was first exhibited at the 1849 Birmingham exhibition. Copeland’s copy appeared in 1852 and other versions followed. Consumers continued to buy replicas for many years. Despite the warnings of connoisseurs that the copies could never duplicate the original, the Victorian middle class did not care if the slave’s thighs were a bit heavy or her head tilted too much to the left; the important consideration was whether the form was “sufficiently correct to study the general proportions of the figure.”[9] Just owning a copy was enough to relive the dramatic moment of having seen the original or, for those who had not seen it, to embrace its reputation.

Parian Porcelain Statuary in America

Despite the fact that little in the way of parian porcelain statuary was made in America before 1870, there was plenty of parian to be had in the shops and markets on this side of the Atlantic Ocean. The art press generated most of the demand for it here, by manufacturers’ exhibits at fairs, and in the shops of urban china and glass dealers. Both Minton and Copeland, for example, showed parian statuary at the New York Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1853. Both firms were awarded bronze medals for their parian, but it was Copeland’s display that Horace Greeley described as having the “gems of their kind in the Exhibition.”[10]

Prominent china and glass dealers in America’s large cities were the primary purveyors of parian. Advertisements in newspapers and trade publications provide the most information on what was available here. Charles Ehrenfeldt of New York advertised “400 DIFFERENT FIGURES OF VARIOUS SIZES” by Copeland, Minton, and Wedgwood during the 1850s. His offerings included John Bell’s Miranda, Hiram Powers’ Greek Slave, a wide variety of political figures, popular personalities such as Jenny Lind, literary figures such as Lord Byron and Charles Dickens, and religious subjects.[11] In 1851, Tyndale and Mitchell, Philadelphia china and glass dealers, advertised James Wyatt’s Apollo, J. J. Pradier’s Ondine, Antonio Canova’s Hebe, and Charles Cumberworth’s Indian Girl and Negress, in addition to those subjects mentioned for Ehrenfeldt.[12]

The United States Pottery Company of Bennington, Vermont, under the direction of Christopher Webber Fenton also exhibited parian at the 1853 New York World’s Fair (fig. 3). Although the largest proportion of this company’s exhibit was earthenwares with mottled brown glazes (called Rockingham), which were the mainstay of the company’s production, the firm also showed four figures, pitchers, a clock case, and a sugar bowl in parian porcelain. Most of the wares were said to be the work of English modelers John Harrison and Daniel Greatbach who immigrated to America during the 1840s from the Staffordshire potteries and worked in Bennington briefly. The pitchers are well-known today from the numerous marked examples that survive; however, the figures have yet to be identified with any certainty.[13] Unique figure groups, one mounted on the top of the company’s display, and a bust of Fenton (fig. 4) attributed to Greatbach, were also included in the exhibit. These are preserved in the collection of the Bennington Museum (fig. 5).

American Sculptors

The enthusiasm for sculpture generated through the parian copies shown in exhibits at the regional, national, and international fairs that proliferated after 1845 was not lost on American sculptors. Even if little parian was actually made in America before 1870, American sculptors had their work translated into this material by factories in England. Hiram Powers’ Greek Slave was highly successful in England where the product was developed. In Boston, on the other hand, between 1850 and 1880, retailers and entrepreneurs commissioned or purchased models of popular subjects from young, ambitious American sculptors such as Thomas Ball, Martin Milmore, and Daniel Chester French. Plaster models from these sculptors were sold to investors along with the rights to reproduce them. The investors then secured the copyright in the United States and arranged for an English pottery or American foundry to make copies in porcelain or metal.

Thomas Ball (1819–1911) describes his experiences with reproducing small-scale sculpture in his autobiography.[14] Early on he tried to profit from the reproductions entirely on his own. However, he found the details of copyrighting and producing to be cumbersome and the fact of pirating to be discouraging. In 1853, on the eve of Daniel Webster’s death, Ball modeled a small, reproducible figure of the statesman (fig. 6). “The first day it was seen,” he later recalled, “I had the very tempting offer of five hundred dollars for the model and the right to multiply it. I accepted the offer with avidity, feeling relieved from any further responsibility. The shrewd art-dealer who bought it must have made five thousand dollars out of it, at the very least. But I could not have done it; so I never murmured, and was only too delighted at the success, and to receive later from the Charitable Mechanics’ Association a first-class gold medal for it.”[15] Ball must have been impressed with his relative success at this venture, and perhaps even discussed it frequently. Two of his students eventually followed the same track.

Martin Milmore (1844–1883) was apprenticed to Ball from 1858 to 1862 and became Boston’s leading sculptor when Ball left for Italy. Between 1860 and 1865, Milmore modeled several pieces that were translated into parian, including a figure of Massachusetts governor John Andrew published by Jones, McDuffee and Stratton, a Boston china and glass dealer (fig. 7). Busts of Governor Andrew and Abraham Lincoln are also signed by Milmore, but the publisher is unknown.

John Rogers (1829–1904) made his living by reproducing his own sculpture. Believing that sculpture should be understood and enjoyed, Rogers used American subject matter and made it in an inexpensive material in order to make sculpture available to many people. His subjects, rendered in profuse detail, were drawn from history, literature, domestic life, and the Civil War soldier’s life. His 208 designs were reproduced in more than 80,000 plaster copies. Although all of his designs were made in plaster, a few have also been found in parian porcelain. Wounded to the Rear – One More Shot (fig. 8) and The Wounded Scout appear in the factory record of Robinson & Leadbeater, a pottery in Stoke-on-Trent, England, that specialized in parian production. The circumstances of the manufacture of these groups in England are currently unknown, but the assignment to Robinson & Leadbeater is based on the factory record of about 1885 now preserved in the Winterthur Museum library.[16]

Daniel Chester French (1850–1931) was also a student of Thomas Ball, working in the sculptor’s studio in Italy beginning in 1876. Furthermore, French and Milmore were close friends. French’s most vivid work, The Angel of Death and the Sculptor (1891–1892), is a memorial to Milmore, who died at a young age. Between 1871 and 1874, French, like Ball and Milmore before him, modeled several pieces that were translated into parian porcelain. However, French’s contributions were not figures of historically important politicians, but rather sentimental ornaments suited to mid-Victorian tastes that favored sweet stories and anthropomorphic attributes. Subjects included owls, dogs, and scenes from popular fiction. Most of these groups also functioned as match safes. Match Making, published by Clark, Plympton & Company of Boston, features a pair of owls nuzzling softly on a branch. Its pendant, a single owl, was called Reveries of a Bachelor. Both were made by Robinson & Leadbeater of Stoke (shapes 249 and 249Q¿™). Similarly, Imposing on Good Nature, also produced by Robinson & Leadbeater (shape 230), shows a large lounging dog being pestered by a small dog. In its pendant, Retribution (shape 231), the large dog is standing and has pinned his tiny playmate to the floor. Joe’s Farewell, also copyrighted by Clark, Plympton & Company and made by Robinson & Leadbeater (shape 235), interprets the passage in Charles Dickens’ Barnaby Rudge, in which Joe Willet calls on Dolly Varden, with whom he was smitten, to say goodbye for an indefinite period of time (fig. 9). The similarity of this group in particular with the work of John Rogers was no accident. French openly admired Rogers’ work and even promoted its historical and artistic importance in later years.[17]

The work of Henry F. Libby (1850–1933), a Boston dentist and amateur sculptor, can also be considered in this group. In the early days of his dental practice during the late 1870s, Libby modeled small sentimental sculpture groups and had them produced by Robinson & Leadbeater of Stoke. Among these are Young Columbus (fig. 10), which features the explorer as a boy dreamer, and Conquering Jealousy, dated 1878, which features a sweet young girl mediating between a large dog and a puppy.[18] After Libby’s dental practice grew, he seems to have abandoned sculpture as a creative outlet. His interest turned to natural history, and in 1912 he founded the Libby Museum in Wolfeboro, New Hampshire.

American Sculptors Work in American Clay

The relationship established between sculptors and manufacturers for the production of parian porcelain statuary in mid-nineteenth-century England and Boston provided the model for the development of the art porcelain industry in the United States. Parian manufactured here in the 1870s was modeled mostly by American and European sculptors, although the reputations of these men today are based mostly on their work in clay. Ott & Brewer found Isaac Broome, the Union Porcelain Works hired Karl Mueller, John D. Parry modeled figures, and W. H. Edge modeled busts for the New York City Pottery.

A Canadian by birth, Isaac Broome (1835–1922) was trained in the United States at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and worked with Thomas Crawford on the statues for the pediment of the U.S. Capitol in 1855/56. In 1860, after having spent a few years in a studio in Rome, Broome became an academician at the Pennsylvania Academy and taught there until 1863. His assignment for Ott & Brewer of Trenton, New Jersey, was to create exhibition pieces in parian porcelain for the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia and models for smaller sculpture that could be purchased by the public. Large vases dedicated to baseball, fashion, and antiquity, busts of political leaders including George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses Grant, Samuel Tilden, Thomas Hendricks, Rutherford Hayes, James Blaine and others, and brackets celebrating the centennial were among the more than twenty models that Broome created in the year or so before the fair when he was working in Ott & Brewer’s shops.

Of these many models, the Baseball Vase is the most important (fig. 11). Western sculpture in general was already moving away from the classical style that had prevailed since the early 1800s, but the subject here is blatantly contemporary and entirely American. The National League had been formed in 1875 and the topic of baseball was on everyone’s lips. The pair of covered vases that flanked Ott & Brewer’s Philadelphia display in the ceramics area of the Manufacturers’ Building attracted so much attention that one was moved to the Art Gallery of Memorial Hall a month after the fair opened in 1876 (fig. 12-15). This is the first American-made ceramic object that was officially given the status of art.

Karl Mueller’s models for the Union Porcelain Works were more nostalgic in nature than Broome’s. Mueller (1820–1887) and his brother, Nicholas, were trained in metalsmithing in Koblenz, Germany, and immigrated to America about 1850. In New York they modeled and cast small-scale sculpture and clock cases in metal. In 1874, Karl was hired to create models for Union Porcelain Works’ display at the upcoming Centennial Exhibition. The Blacksmith is a larger version of the same figure that Mueller had patented in 1868 and produced in white metalxix (fig. 16). Like Rogers with his groups, Mueller in his portrayal of the blacksmith seeks to monumentalize the labor of the common American while recording the details of his life and craft.

James Carr (1820–1904) operated his New York City Pottery beginning in 1853, but did not make parian porcelain statuary until the early 1870s. John D. Parry (1845–1945), a native of Vermont and resident of Boston and Rome, modeled the seated figure of Charles Sumner in the early 1870s for Carr (fig. 17). He may also be the sculptor for the group Meeting of Jacob and Rachel (fig. 18), which won high praise when it was exhibited at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia and the American Institute Fair the same year in New York City. In 1876, Carr employed a sculptor to develop additional models for the Centennial Exhibition. W. H. Edge, previously identified with the ceramic industry in Trenton, modeled busts for the display, including George Washington, Ulysses Grant, and perhaps Carr himself (fig. 19, 20). Carr’s pottery received a gold medal for its parian at the Centennial Exhibition, and subsequent exhibits of the pottery’s parian received similar high praise. Indeed, one writer in 1876 compared Carr’s work to Copeland’s.[21]

Parian’s Legacy

Thomas Ball and Daniel Chester French noted in their respective remembrances that good profits were made by entrepreneurs claiming a sculptor’s hand as the source for the figure or group. A Minton figure of The Greek Slave, for example, was priced at £1.105 in 1917, but was produced at a cost of 3/6d. Minton’s Dorothea, which was enormously popular over a long period of time, cost the consumer two guineas in London at the time when most workers were bringing home wages of less than £1 per week.[22] Similarly, Ott & Brewer asked china dealers to pay $250 in the 1880s for the Baseball Vase, an enormous price in its day but still less than what the retail customer would have been charged. It is probably safe to say that no one ever paid this huge price, but the wholesale cost of $32.00 per dozen for small busts of George Washington left plenty of room for profit while making the sculpture available to a middle-class retail audience.

In America, the success of parian in terms of the publicity it generated encouraged the development of the art porcelain industry. Until the centennial, American-made ceramics were notable primarily for their durability and cheapness, first as redware pots, then as utilitarian stoneware and yellow ware, and finally as white ironstone tableware. Attempts to make finer porcelain wares from the late eighteenth century on had been foiled by the high cost of American labor unprotected by import duties on wares from abroad. Furthermore, the reputations of English and French manufacturers continued to plague American firms who often disguised the domestic origin of their wares by imprinting them with marks that looked English.

When American sculptors began modeling for parian porcelain, the subject matter they chose had a classically American character. Daniel Webster, John Andrew, Charles Sumner, George Washington, Ulysses Grant, and especially baseball were subjects of interest to many Americans. Although there had been the stray figure of Washington sent over from England by the Staffordshire potters, the wide array of American politicians and popular subjects chosen by the American sculptors was far more nationalistic.

The reaction to American parian was encouraging to the fledgling American pottery industry. Ott & Brewer, for example, went on to develop an American version of Irish Belleek in the early 1880s that established a reputation for fine art porcelain made in Trenton. The Willets Manufacturing Company expanded production there, and the success of both firms in marketing fine porcelain encouraged Walter Scott Lenox in 1889 to open the first studio for making and decorating art porcelain exclusively in the United States.[23]

The subjects and style of parian changed between 1845 and 1885 as sculpture developed from the early neoclassicism that favored ideal figures and antique replicas to the later Victorian preference for sentimental story-telling, but the medium did not survive changing ceramic fashions or the general movement toward owning original art and decorating with handmade objects. Trade advertisements of the 1880s favored majolica, a molded earthenware painted in glossy brightly colored glazes. Unlike white parian, majolica’s colorful style incorporated all the popular Japanese motifs and naturalistic subjects that appealed to the fashionable homemaker.

At the same time, the late nineteenth-century desire for honest use of materials belied the idea central to parian’s popularity, that clay could imitate marble that mimicked drapery. The aesthetic movement followed by the arts and crafts movement in England and America saw parian as one of the gew-gaws that was to be stripped from the parlor. The old idea that a reproduction represented the original work of art in a positive way passed from the scene, although there were at least a few who were sorry to see it disappear. “Why is it we get so few parian imitations of the works of the great masters now?” whined a commentator for the London Pottery Gazette in 1884. “We fear it is the patrons which are wanted, not the will or ability to do on the part of our manufacturers. One of the things aestheticism did for us was to make it vulgar to have copies in art. . . . It is a mistake to imagine that art only exists in the most cultured or the most wealthy. . . . Of all exclusiveness, exclusiveness in art is the most to be lamented.”[24]

Parian porcelain statuary has been in the attic for more than a century, victim of the modern attitudes that give value to original products of the artist’s hand, but not to objects that replicate, even faithfully, the finished work of art. Parian is not art and never was meant to be. But its character—the product of an alliance between artists and manufacturers—laid the foundations for the twentieth-century embrace of design as a democratic art form available to everyone and the century’s active market for the work of studio ceramists.

For more on the background of English parian porcelain statuary, see Paul Atterbury, ed., The Parian Phenomenon: A Survey of Victorian Parian Porcelain Statuary & Busts (Somerset, Eng.: Richard Dennis, 1989).

See ibid., fig. 2, for an illustration of Cheverton’s machine which could reduce or enlarge sculpture by use of a gearing system that united two pointers, one on the original work and the other on the material being used for the reduction or enlargement.

Illustrated London News, July 26, 1851.

Gibson was quoted on the title page of Copeland’s illustrated catalog of parian published about 1848. See Atterbury, Parian Phenomenon, p.19.

Art Union Journal (1839), p. 20, quoted in Roger Smith, “The Art Unions,” in Atterbury, Parian Phenomenon, p. 27. Art unions developed in Great Britain in the mid-1830s after art lotteries were outlawed. Based on successful German schemes, the art union offered subscribers works of contemporary British art as prizes awarded through annual drawings.

Art Union of London, Annual Report (1840), p. 10.

Courier and Enquirer, August 31, 1847, quoted in Samuel A. Robinson and William H. Gerdts, “The Greek Slave,” The Museum 17, nos. 1 & 2 (new series, winter/spring 1965): 16. For more information on Powers’ sculpture and its reverberations through nineteenth-century society, see also Linda Hyman, “The Greek Slave by Hiram Powers: High Art as Popular Culture,” Art Journal 35, no. 3 (spring 1976): 216–23.

Mrs. Merrifield, “Dress as Fine Art,” Godey’s Lady’s Book 47 (1853): 20.

Ibid.

Horace Greeley, Art and Industry: As Represented in the Exhibition at the Crystal Palace. New York—1853–4(New York: Redfield, 1853), p. 118.

Ehrenfeldt’s advertisement appeared in The Crayon, an art journal published in New York City.

Tyndale and Mitchell’s advertisement appeared in the Philadelphia Art Union Reporter, February 1851.

For more information on the parian products of the United States Pottery Company, see Deborah Anne Federhen and Ellen Paul Denker, “The Bennington Parian Project: An Analytical Reevaluation of the Bennington Museum Collection,” Antiques and the Arts Weekly (October 1998). Greeley, Art & Industry, notes this company’s parian as being “remarkably fine, especially in the form of pitchers” on p. 122.

Thomas Ball, My Threescore Years and Ten: An Autobiography, 2nd ed. (Boston: Roberts, 1892), pp. 141–42.

Ball, My Threescore Years, p. 142. The “shrewd art-dealer” to whom Ball refers was George Ward Nichols who had an art store in Boston at the time. Nichols is listed as the assignee of the Webster statue by Thomas Ball on August 9, 1853, in Report of the Commissioner of Patents for the Year 1853 (Washington, D.C.: Beverly Tucker, Printer to the Senate, 1854), p. 89. Nichols later married Cincinnati socialite Maria Longworth, who founded the Rookwood Pottery in 1880, and is best known for his critical review of the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876, Art Education Applied to Industry (New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1877).

Wounded to the Rear is shape 398 in the Robinson & Leadbeater factory record and The Wounded Scout is shape 549. Other Rogers groups in parian include Checker Players, CampLife: The Card Players, Union Refugees, Taking the Oath and Drawing Rations, and Courtship in Sleepy Hollow. Perhaps they were also produced by Robinson & Leadbeater, which advertised in the Crockery & Glass Journal on December 28, 1882, that “new designs, by first-class American and other artists, are constantly being added.”

For more on Rogers and his relationship with his contemporaries, see Michele H. Bogart, “Attitudes Toward Sculpture Reproductions in America 1850–1880” (Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago, 1979).

The Robinson & Leadbeater factory record shows Conquering Jealousy as shape 371 (p. 17 112) and Young Columbus as shape 321 (p. 43 112), Joseph Downs Library, Winterthur Museum. Young Columbus was copyrighted in 1876.

For illustrations of the design patent and the metal statuette, see Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, American Porcelain, 1770–1920 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989), p. 157.

Ibid., pp. 158–60.

“The American Institute,” Crockery & Glass Journal (October 5, 1876). For more on Parry and Edge, see Caroline Hannah, “James Carr (1820–1904) and His New York City Pottery (1855–1889)” (masters thesis, Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts, 2000), pp. 74–75, 89.

Atterbury, Parian Phenomenon, p. 10.

For more on W. S. Lenox and the development of Belleek in Trenton, see Ellen Paul Denker, Lenox China: Celebrating a Century of Quality, 1889–1989 (Trenton, N.J.: New Jersey State Museum and Lenox China, 1989).

London Pottery Gazette, 1884