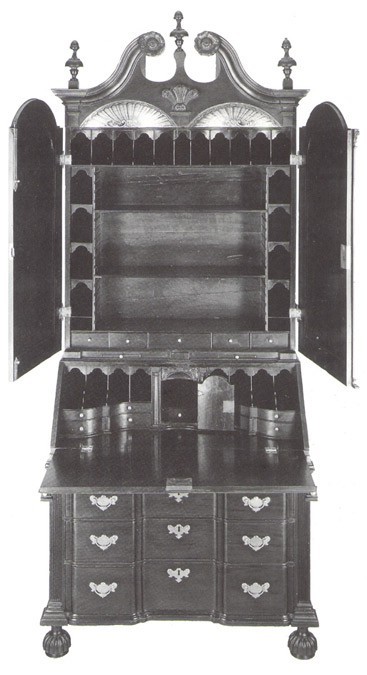

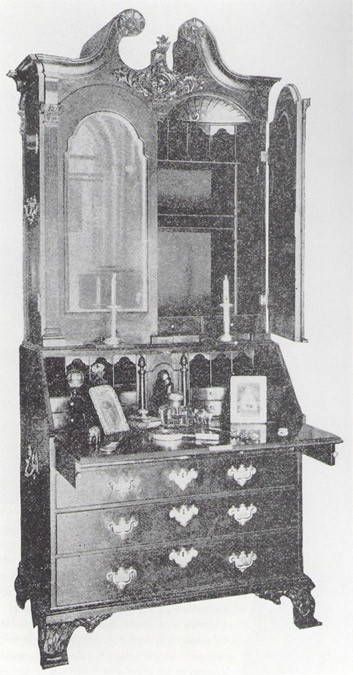

Desk-and-bookcase, Boston, 1735-1740. Courbaril, red cedar, and cherry with white pine, cherry and oak. H. 97", W. 40 5/16, D. 24 1/8". Milwaukee Art Museum purchase through bequest of Mary Jane Rayniak in memory of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Rayniak, acc. M1983.378; photo, Richard Cheek.) The scrollboard appliqué, finals, brass, and glass door plates are restored.

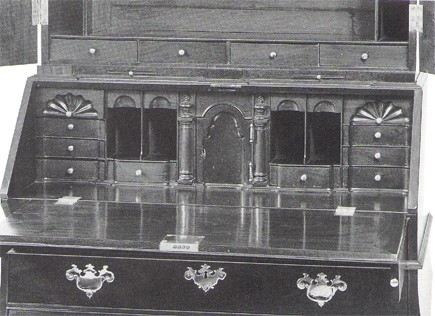

Interior of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Richard Cheek.) The door panels and large scrolled vertical dividers of the bookcase and the prospect door of the desk interior are restored.

Detail of the interlocking drawers and prospect box of the desk- and- bookcase illustrated in fig. 2 (Photo, Milwaukee Art Museum.) The lock on the prospect door of the bookcase controls access to eight smaller drawers. When this door is open, a wooden spring lock releases the fascia drawer above and sliding wooden bolts let into the underside of the shelf release the two Doric column document drawers. These interlock with drawers above and below. The prospect section of the desk is held with two wooden spring locks. It houses two secret document drawers and originally concealed a secret compartment faced by a hinged false backboard.

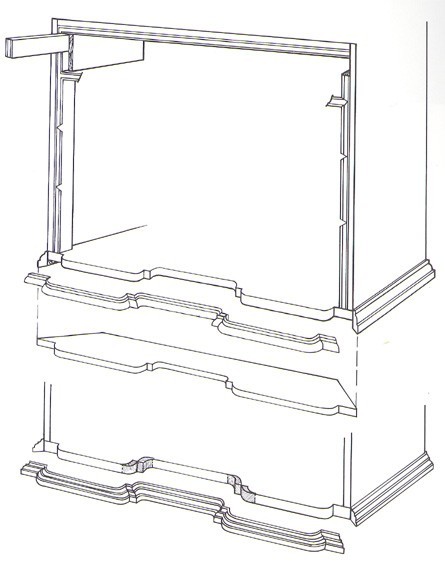

Diagram of (a) base-molding and fallboard support construction of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 1; (b) base-molding construction of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 5. The shaded areas on the front of the bottom board in b represent the patches resulting from layout or construction error. (Drawing by Alan Miller; artwork, Bradley K. Szollose, K2 Design.)

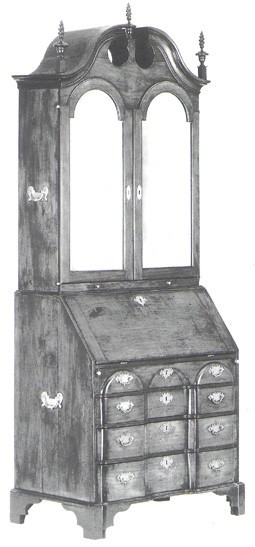

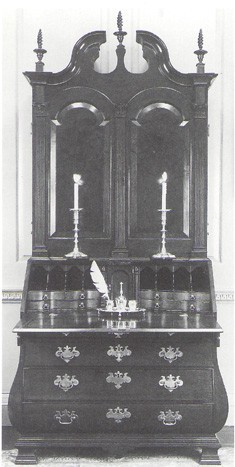

Desk-and-bookcase, signed by Job Coit and Job Coit, Jr., Boston, dated 1738. Black walnut with white pine. H. 99 1/2", W. 39 5/8", D. 24 3/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, acc. 62.87.)

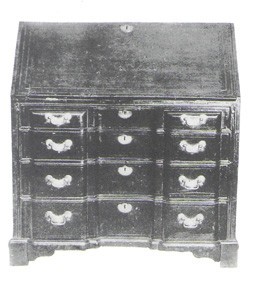

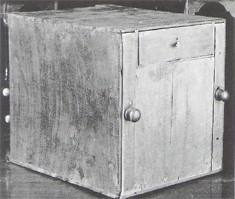

Desk, Boston, dated 1739. Possibly walnut, secondary wood undetermined. H. 41 1/2", W. 37 1/2", D. 21 1/2". (Lot 1349, The Jacob Paxon Temple Collection of Early American Furniture, Anderson Galleries, 1922.)

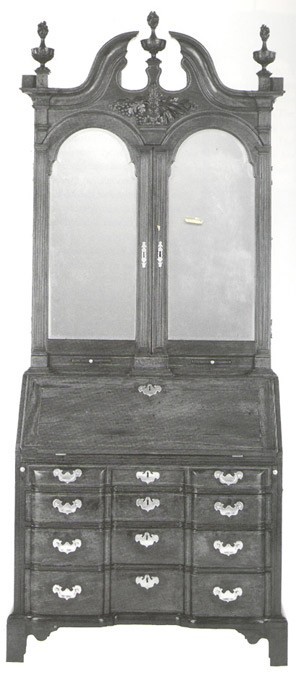

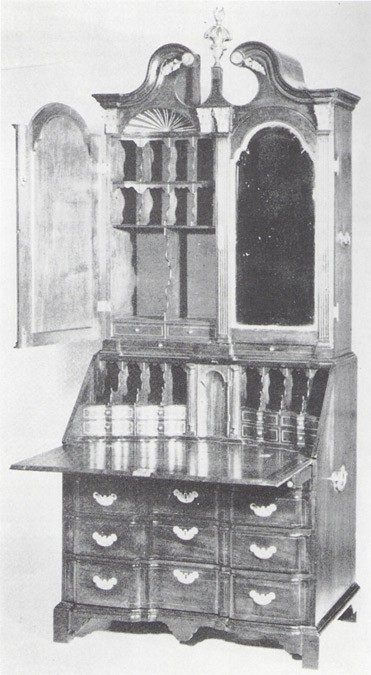

Desk-and-bookcase with carving possibly by John Welch, Boston, 1733-1738. Mahogany with oak and white pine. H. 94", W 41 1/4", D. 24". (Photo, Joe Kindig, III.) The left finial is original, and the original center finial is shown on the right corner. The finial in the center is incorrect. The top central portion of the scrollboard and a small piece of carving at the top of the appliquÈ are missing. The mirrors and backing panels, hardware, and feet are replaced. The bottom of the desk section had no evidence of bracket feet.

Desk-and-bookcase, unknown artist , Boston, MA, 1740-1750; illustrated in fig. 7. (Art Institute of Chicago, major acquisitions Centennial Fund, acc. 1986.414; digital file, ©The Art Institute of Chicago. All rights reserved.)

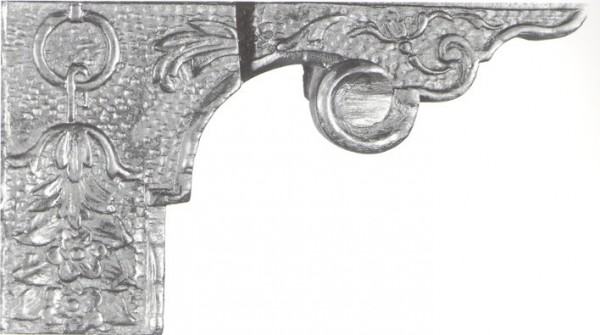

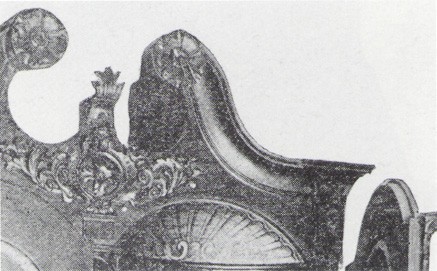

Detail of the scrollboard applique and center finial of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figs. 7, 8. (Courtesy of Sack Heritage Group)

Desk-and-bookcase with carving attributed to John 'Welch, Boston, 1740-1760. woods and dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Bernard & S. Dean Levy, Inc., N.Y.C.)

Detail of the applique and painted gilt shells of the bookcase illustrated in fig. 10.

Detail of the applied shell and upper rail of a picture frame carved by John Welch for John Singleton Copley's portrait of Nicholas Boylston, Boston, ca. 1767. White pine, gilded. 66 3/4" x 47 3/8". (Courtesy of the Harvard University Portrait Collection, bequest of Ward Nicholas Boylston to Harvard College, 1828, ©President and Fellows of Harvard College, acc. 1828 H 90.)

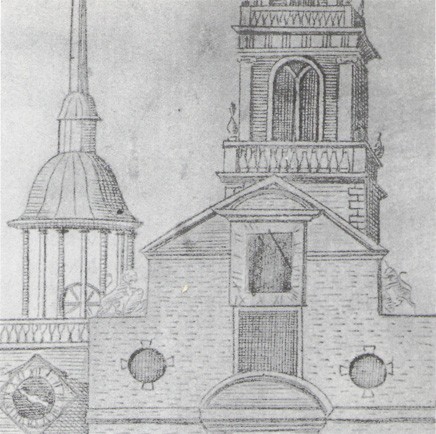

Detail of Paul Revere's The Bloody Massacre Perpetuated in King Street Boston on March 5th 1770. Colored engraving on paper. 9 5/8" x 8 5/8". (Chipstone Foundation, ace. 1969.1; photo, Gavin Ash-worth.) This engraving shows the lion and the unicorn carved by Welch.

Detail of a Corinthian capital carved by John Welch for the State House illustrated in fig. 13. (Photo, Luke Beckerdite.)

Desk-and-bookcase with carving attributed to John Welch, Boston, 1743—1748. Mahogany with sabicu, red cedar, and white pine. H. 97 1/4", W. 42 3/8", D. 23 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, acc. 60.1134.) One Corinthian capital, part of one rosette, and the extreme side elements of the scrollboard appliquÈ are restored. A hand drawn cartouche, illegible writing, and what may be the date 1746 is on a backboard of the prospect section of the desk. the desk also has a nineteenth-century inscription, "This desk was purchased by Josiah Quince Braintree 1778."

Open view of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

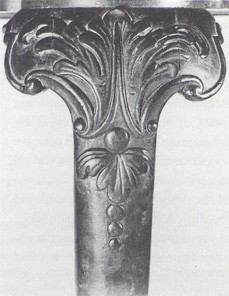

Detail of Corinthian capital from the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail of the appliqué on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail of the left front foot of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Desk-and-bookcase with carving attributed to John Welch, Boston, ca. 1751. Mahogany with white pine. H. 97", W. 40 1/2". (38" case), D. 23" (21 1/4"case). (Chipstone Foundation, acc. 1991.6; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The brasses and molded faces of the fallboard supports are restored.

Detail of the right pilaster and gadrooned ball foot of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 20. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Open view, of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 20. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The carved appliques on the fascia above the prospect door are restorations based on the spandrel appliques of the clock case illustrated in figs. 27, 30.

Detail of the finials, rosette, applique, painted gilt shell, and Corinthian capital of the bookcase illustrated in figure 20. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the back of the prospect box of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 20. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inscription and drawing on the side of a document drawer from the prospect box illustrated in fig. 24. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

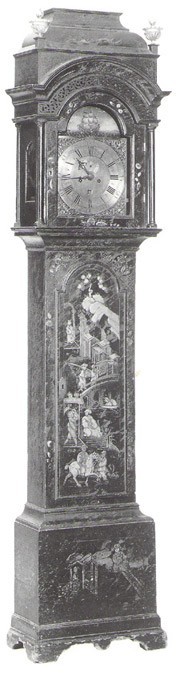

Tall case clock labeled by George Glinn, with carving attributed to John Welch, Boston, 1750. H. 100". (Digital file © The Art Institute of Chicago, All rights reserved. Alyce and Edwin DeCosta and Walter E. Heller Foundation and Harold Stuart endowments, acc. 1990.395 photo, Sotheby's.) The case houses a movement by London clockmaker Thomas Hughes. The capitals of the waist pilasters and the center finial and plinth are missing.

Detail of the hood of the clock case illustrated in fig. 27. (Digital file, ©The Art Institute of Chicago. All rights reserved.)

Detail of the right foot of the clock case illustrated in fig. 27. (Digital file, ©The Art Institute of Chicago. All rights reserved.)

Detail of the right spandrel appliqué of the clock case illustrated in fig. 27. (Digital file, ©The Art Institute of Chicago. All rights reserved.)

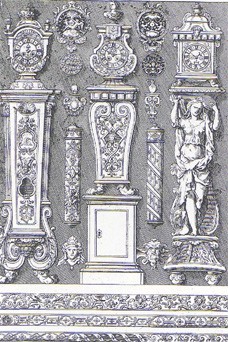

Plate 21 in Daniel Marot's Nouveau Livre d'Ornements (ca. 1703). (Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University.)

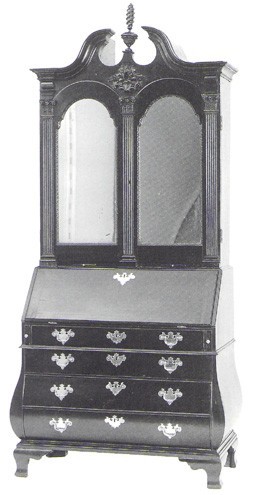

Tall case clock with carving attributed to John Welch, Boston, 1751-1754. Mahogany with mahogany and white pine. H. 96", W. 21 3/4", D. 11". (Chipstone Foundation, acc. 1992.12; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The case houses a movement by London clockmaker Marmaduke Storr. The sarcophagus top and finials are missing, and the original arch fret and spandrels are replaced with burl veneer.

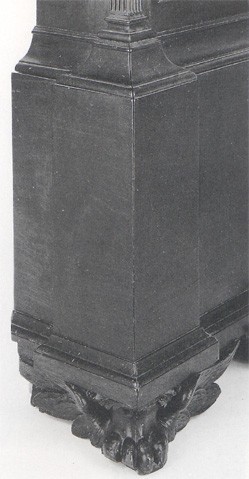

Detail of the base of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 32. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the hood of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 32. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

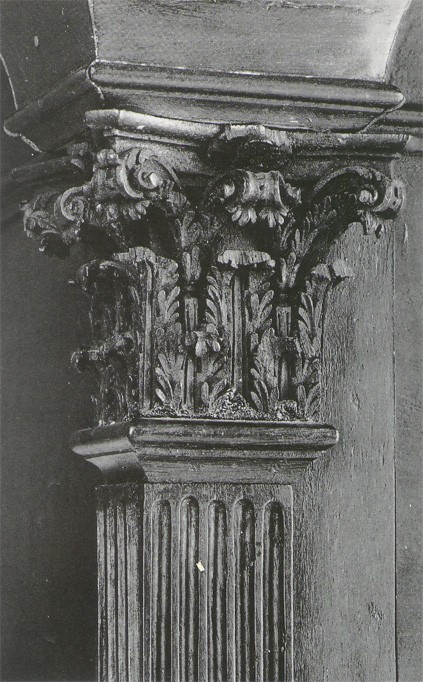

Detail of the left Corinthian capital of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 32. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall case clock with movement by Samuel Bagnall, Boston, 1740-1745. Mahogany. H. 93", W. 18 1/2". (Courtesy of Sack Heritage Group) The sarcophagus top is restored.

Tall case clock with movement by Samuel Bagnall, Boston, 1740-1745. Mahogany with white pine. H. 100 1/2", W. 21 3/8", D. 11". (Private collection; photo, LeVan Design.)

Detail of the hood and face of the movement of the tall case clock illustrated in fig. 37. (Photo, LeVan Design.) The finials, outer plinths, and upper concave element of the sarcophagus top are restored. The arch fret is a restoration based on surviving sections of the original frieze fret.

Tall case clock, Boston, 1745-1755. White pine. H. 94 1/2", W. 22 1/4", D. 10 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, acc. 55.96.3.) The Gawen Brown movement, finials, and arch fret of the hood are replaced. The original center plinth, scrolled brackets, and finial of the top are missing.

Desk-and-bookcase with carving attributed to John Welch, Boston, 1750-1754. Mahogany with white pine and red cedar. H. 94 1/2", W . 41 3/4", D. 22 3/4". Photo of p. 118 in the 1902 ed. of Francis Clary Morse's Furniture of the Olden Time.)

Detail of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 40.

Detail of the right front foot of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 40. (Private collection; photo, Brock Jobe.)

Desk-and-bookcase with carving attributed to John Welch, Boston, 1751-1756. Mahogany with white pine. H. 95 1/2", W. 40", D. 22". (The Saint Louis Art Museum, Museum Shop Fund, acc. 84:1989; photo, Christie's.) The scrollboard is cut, and the roof and back boards of the head are missing. The original upper portion of the scroll moldings and scrollboard were reattached except for the center portion. The lower portions of the feet are restored and wood panels replace the original mirrors.

Detail of center finial, scrollboard applique, center capital, and carved molding of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 43. (The Saint Louis Art Museum, Museum Shop Fund, acc. 84:1989; photo, Christie's.)

Desk-and-bookcase with carving attributed to John Welch, Boston, 1751-1756. Mahogany with white pine. H. 97 1/2", W. 45", D. 23". (The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Bayou Bend Collection, gift of Miss Ima Hogg, acc. B.69.363.) The feet, base molding, finial, drawers, and possibly the appliqué are restored.

Detail of the desk interior of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 45.

Detail of the pediment and carved shells of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 45.

Desk-and-bookcase signed Benjamin Frothingham, Boston, 1753. Mahogany with red cedar, cedrela, and white pine. H. 98 1/4", W. 44 1/2", D. 24 3/4". (Diplomatic Reception Rooms, U.S. Department of State, acc. 70.94; photo, Will Brown.) The mid-molding and finials are restored.

Interior of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 48.

Desk-and-bookcase with caning possibly by John Welch, Boston, 1750-1756. Mahogany with white pine and oak. Dimensions not recorded. (Photo of an illustration on page 135 of the 1917 ed. of Francis Clary Morse's Furniture of the Olden Time.)

Card table with carving attributed to John Welch, Boston, 1745-1755. (Private collection; photo, courtesy, John Walton Antiques.)

Detail of the knee of the card table illustrated in fig. 51. (Photo, John Walton Antiques.)

Detail of the mask knee of a pier table, carving attributed to John Welch, Boston, 1745-1760. Mahogany, H. 29", W. 28 1/2", D. 17 1/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The M. and M. Karolick Collection of Eighteenth Century American Arts, acc. 41.586. Reproduced with permission. © 2000 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All rights reserved.)

Desk-and-bookcase, Boston, 1738—1748. Black walnut with white pine. H. 98", W. 41 1/2". (Parke-Bernet Galleries, Inc., Important XVIII Century American Furniture From the Collection of Maurice Rubin, Brookline, Mass., October 9,1954, lot. no. 174.) The gilt Corinthian capitals, festooned rosettes, and finials are above a cut line about four inches from the top of the scroll moldings.

Desk-and-bookcase, Boston, 1738—1748. Mahogany with white pine. H. 94", W. 40 1/2", D. 22". (Courtesy, Bernard & S. Dean Levy, Inc., N.Y.C.) The feet and everything above the bookcase doors are restored.

In 1767, German economist Justus Moser meticulously described the responsibilities of the master cabinetmaker in a large London shop:

The master himself no longer touches a tool. Instead he oversees the work of his forty journeymen, evaluates what they have produced, corrects their mistakes, and shows them ways and methods by which they can better their work or improve their technique. He . . . will observe what is going on in the development of fashion. He keeps in touch with people of taste and visits artists who might be of assistance to him.

Although few colonial cabinet shops were as large as that described by Moser, many were hierarchical organizations in which the master, journeymen, and contractors had clearly defined roles. Design and construction details that identify a large group of furniture from a now anonymous Boston cabinet shop (fl. 1735-1755) provide compelling evidence of a differentiated designer/tradesman relationship and a level of specialization that was comparable with urban British practice.[1]

The furniture from this shop represents the collaborative efforts of several talented artisans - a designer, joiners, and at least one japanner, one turner, and one carver-and is the most advanced work from eighteenth-century Boston. What most distinguishes this furniture is its complex, varied design. As a group, these pieces reflect an intimate understanding of late-seventeenth-century baroque style, Palladian classicism, and the furniture traditions of eighteenth-century Boston. This is not urban British furniture made in the colonies; it is Boston furniture informed and transformed by the grandeur of European styles. Two explanations or this remarkable diversity can be proposed: either a Britishtrained esigner assimilated Boston styles, or a Boston native moved to England during the first quarter of the eighteenth century, absorbed the intentions and details of then-current furniture and architectural design, and returned to design at home.[2]

If the designer was a Boston native he probably went to England during the 1720s or early 1730s when British architects and cabinetmakers began to abandon the baroque style and embrace the new classical interpretations, or Roman "gusto," of Lord Burlington and his protégés. If he was an immigrant, like Boston cabinetmaker William Price (1684—1771), he remained acutely sensitive to changes in British fashion. Price emigrated from London in 1714 and enjoyed a long and prosperous career as a merchant, picture seller, and cabinetmaker. As an importer of maps and prints he maintained close ties with England and reportedly made "recurring visits to the land of his youth." Commercial contacts and associations with other tradesmen helped keep colonial artisans informed of the latest styles. Price, for example, apparently employed at least one London-trained cabinetmaker. In 1726, he advertised "All Sorts of Looking-Glasses of the newest Fashion, & Japan Work, viz. Chests of Drawers, Corner Cupboards, Large and Small Tea Tables & c. done after the best manner by one late from London . . . ."[3]

Social contacts were nearly as important as skill for an eighteenth-century artisan, especially if he was designing or making expensive goods that were attainable only by the very affluent. The designer of this group of Boston furniture probably occupied a social position comparable to Price, who was an accomplished organist and influential figure in the design and furnishing of Anglican churches in Boston. Price's ability to supervise workmen and his knowledge of classical architecture prompted the trustees of Trinity Church to hire him in 1738-1739 to "Treat with a Carver about the Corinthian Capitals.”[4]

Although there is no documentary evidence that Price was the designer of the furniture under discussion, his background, his commercial and social connections, and his career as a cabinetmaker and architectural designer fit the profile almost perfectly. He maintained a long association with Boston japanner, engraver, and organ builder, Thomas Johnston, and had business dealings with wealthy Boston merchants Peter Faneuil, James Bowdoin, and Thomas Hancock. More importantly, Price apparently had the financial resources to support a large cabinetmaking enterprise.[5]

Colonial artisans were essentially pieceworkers in a labor system where habit and repetition increased speed and generated profit. Although most American furniture was the result of rote practice rather than innovative design, the pieces attributed to this Boston shop are novel and reminiscent of the playful architectural fantasies of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century gentleman architects. Almost every foot design and ornamental detail is different from others in the group and from anything else produced in eighteenth-century Boston. Creating new designs and working them out on the shop floor was expensive, but this creator was interested in intellectual rather than habitual design. His shop also used expensive imported materials: exotic woods, fine brass hardware, silver and gold leaf, and Vauxhall plate glass-beveled, shaped, and silvered for door mirrors.[6]

The tradesmen who made these pieces were among the most skilled in eighteenth-century Boston, yet evidence suggests that they were only peripherally involved in the design. Joiners, for example, evidently misunderstood certain details and constantly improvised and invented new construction methods to execute them. On most desks-and-bookcases, the plinths of the scrollboard appliqués are awkwardly fitted around the door arches (figs. 9, 22, 23, later in this article). If the designer was one of the artisans in the shop, he clearly was orchestrating most of the work, rather than doing it himself. If not a cabinetmaker, then he may have been involved in a related trade such as architecture.[7]

Boston furniture makers formed a relatively closed, interrelated trade group by the second decade of the eighteenth century. Because immigration was negligible after the mid-1720s, most tradesmen were from families that had been in New England for several generations. The eclaved craft system and general conservatism ofthe furniture-buying clientele led to standardized furniture designs and construction techniques. In the use of urban British construction details-thin oak and red cedar backboards and drawer frames, 3/4-depth dustboards, and composite foot blocks-ornate carving and japanning, and rigorous architectural design, the furniture attributed to this shop represents a significant departure from mainstream Boston work. Wealthy, cosmopolitan merchants, such as Col. Henry Bromfield and Gilbert Deblois, provided the initial market for these new furniture designs, which gradually inspired shop-tradition manufacturers who catered to Boston's middle class.[8]

An early desk-and-bookcase from this group (fig. 1) and a contemporary example from another Boston cabinet shop (fig. 5) graphically illustrate this point. Figure 5 is signed by Job Colt and Job Colt, Jr., dated 1738, and is the earliest documented piece of Boston (or American) blockfront furniture. Except for the blockfront and shaped desk interior, it is a standard Boston form made from walnut and white pine. The Colts obviously struggled to execute the blocked design (fig. 4). Although they cut the back edge of the base molding to the same shape as the front edge and attempted to cope the molding to the bottom board, patches on the board indicate that it was either cut initially for a different block facade or that the Colts made a layout mistake. They did not have a template or standard layout system for blocked base moldings, and they were unfamiliar with blockfront construction techniques.[9]

They also were unaccustomed to making drawers with receding fronts for the writing compartment of the desk. The sides of the drawers do not meet the fronts in right angles because of the curved interior design. The shoulders of the dovetails of these drawer sides should conform to the angles of the fronts to which they are attached. As the Colts executed them they do not; some of the drawers with asymmetrical plans have their side's front shoulders cut as though the plan were symmetrical. Different drawers are handled in different ways, and they did not settle on a systematic accurate way to make them during the manufacture of this desk-and-bookcase despite their experimentation.[10]

The Colts were attempting to produce a simplified version of the 1735-1740 desk-and-bookcase (fig. 1), which is part of the group of furniture upon which this article focuses. Unlike the Colt piece, the desk-and-bookcase in figure 1 represents the efforts of a designer, a British-trained joiner who was capable of executing exacting inlay work, a turner, a japanner, and a carver. It is the product of either a large organized shop or a carefully orchestrated network of subcontractors working with a cabinet shop.

The case is made of three primary woods, two of which are expensive exotics. The facade, feet, and moldings are made of Hymenea courbaril (guapinol, locust or rode lokus, algarrobo and Jatoba), a tropical hardwood whose growth range extends from southern Mexico and the West Indies to northern Brazil. A very heavy wood with tightly interlocked grain, courbaril is extremely difficult to work with edge tools. Because its red color is very fugitive and its pores are sparse and large, courbaril offers few advantages over mahogany and is rarely encountered in eighteenth-century furniture. Its use in this piece probably stems from its temporary availability in the mahogany trade and reflects the experimental inclinations of this designer/shop. Red cedar is the primary wood of the interior, and its selection may have resulted from exasperation over working with courbaril (figs. 2, 3). When freshly cut the woods are almost the same color. The cedar came from large trees and is Juniperus species, likely either bermudiana or silicosa, which are Caribbean and southeastern North American woods respectively. In Boston, red cedar was an expensive, exotic wood valued as highly as mahogany. Its smooth working qualities, color, aroma, and insect deterrence undoubtedly contributed to its popularity. Red cherry, a local hardwood that also is nearly the same color as courbaril when cut, was used for the case sides.[11]

Where the Coits' construction was either rote or uncertain, the structure of this desk-and-bookcase is exceptional. The desk has large drawers with thin frames and fine dovetails, 3/4-depth dustboards, and embryonic composite feet-details that indicate that at least one of the shop joiners was British trained. The attachment of the base molding involved coping the ovolo element to the bottom board and gluing it to a shaped plate below, a construction technique that the Coits unsuccessfully attempted to emulate (fig. 4). The designer and joiners also devised a complex method to keep the fallboard supports from intruding on the top drawer. To raise the bookcase doors above the arc of the fallboard, the joiners made a horizontally configured box and attached it to the base of the bookcase. This box also houses the candle slides, which have molded recesses produced by turning them on the faceplate of a lathe.

. The interior of the bookcase follows London designs of the 1720s and earlier and is one of the most elaborate produced in the colonies (fig. 2) . The fascia, or valence, over the prospect door has a relieved ground and a beaded edge worked from the solid. Flanking the door are interlocking, three-part document drawers that separate at the junction of flame, Doric column, and plinth (fig. 3). The desk interior also has a central prospect with a beaded fascia, engaged Doric columns, and tiers of small blocked drawers surmounted by pigeonholes with shaped dividers and valences. The door, columns, and flanking convex drawers are encased in a removable cedar box that is held in place with two wooden spring locks. Document drawers behind the engaged columns are accessible only from the back. An elaborate secret compartment was behind the removable box, but all that remains are shallow mortises for two leather hinges for a false back that was lowered like a drawbridge.

An accomplished japanner and carver contributed to the grandeur of this piece. The bookcase interior has silver gilt moldings and flames, and trompe l’oeil shells and moldings (figs. 2, 3). The Japanner used several techniques to produce the trompe l‘oeil effect: he probably tarnished the silvered shells with liver of sulfur, shaded selected areas with dilute asphaltum, and made bright accent lines using sgraffito techniques. Although any competent japanner should have been able to perform this work, silver gilding of this quality is rare in colonial furniture. The carved scrollboard appliqué and finials of the desk- and- bookcase are lost; however, they probably resembled those currently on the piece. The flames of the finials probably matched those on the columns in the bookcase, which have quadruple bine twists with beads worked in the valleys. Despite its losses, the bookcase is more elaborately and extensively carved than most Boston examples of the 1730s.

In its materials, joinery, and ornament, this desk-and- bookcase represents the pinnacle of its era in Boston; yet, its most remarkable feature is its design. It successfully combines late baroque features (such as the elevated returns of the cornice) with classical architectural details (such as Doric columns). Four engaged pilasters on the bookcase facade and two pairs of engaged columns in the interiors make it one of the most architectonic pieces surviving from the colonies. The designer's meticulous attention to detail is reflected in the integration of the outer pilasters into the cornice molding to create a full classical entablature. When this piece was made (1735-1740), the blockfront style was just emerging in Boston, and if this designer did not actually introduce that style, his shop certainly gave it enough credence to ensure its survival. It would be difficult to overstate this influence on eighteenth-century Boston furniture. This designer's experiments became the standard, almost habitual, formats of later cabinetmaking traditions.

A blockfront desk, formerly in the collection of Jacob Paxon Temple, supports the 1735-1755 date range assigned to this designer's work (fig. 6). Although its present location is unknown, the 1922 auction catalogue stated that the desk in Temple's collection was made of walnut with line inlay and floral marquetry, fitted with "small drawers and pigeonholes on either side of [a] central arched and locked compartment, with four small drawers and a secret compartment," and dated 1739. Except for the inlay on the lid, slightly different brasses, and walnut (which may have been incorrectly identified), the desk is virtually identical to the desk section of the preceding piece. [12] The authenticity of the date and age of the inlay on the fallboard cannot be verified, but they probably are genuine, for early-twentieth-century furniture historians would have considered 1739 much too early for a blockfront, making it unlikely that the date was added to increase the piece's value. Moreover, the date fits perfectly with the chronology posed for this group. The joiner who inlaid the preceding desk-and-bookcase (figs. 13) undoubtedly was capable of executing compass-generated vine and flower inlay. Such inlay was common throughout the western world during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

The remarkable desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figures 7 and 8 is the earliest known piece by this designer/shop and could be the earliest piece of American blockfront furniture. Although currently fitted with blocked bracket feet, it probably had turned ball feet similar to those of a later desk-and-bookcase from this shop (fig. 20). A photograph taken in the late 1940s shows the piece with late neoclassical turned feet that may have been tenoned into the sockets of the originals (fig. 7). The blocked desk interior likely predates the half-amphitheater format of the courbaril desk-and-bookcase (fig. 2) and the full amphitheater format of later desks from this shop (figs. 16, 22, later in this article).

Although most of the patterns, molding planes, and scratch stock cutters used to make the desks-and-bookcases in figures 1 and 7 are the same, the appearances of these pieces are remarkably distinct. The earlier example has more carving-large urn-and-flame finials and a scrollboard appliqué with clusters of grapes, flowers, and leaves -than other contemporary Boston furniture (figs. 7, 9). In stylistic intent, the appliqué recalls the work of London carver Grinling Gibbons (1648-1721) . It is as naturalistic as its maker's technique will allow. The long-petaled flowers on the right side are carved in full relief and their front petals project 1 ½". This seventeenth-century style carving could be considered old-fashioned when compared to the case design, but its bold declaratory quality is consistent with Palladian designs, which frequently include large-scale naturalistic carving. In design and ornament, this desk-and-bookcase has only one contemporary parallel from Boston-the courbaril example (fig. 1).

Although not examined by the author, a desk-and-bookcase illustrated in Antiques in December 1947 has an upper case with details consistent with several pieces by this Boston designer/shop and appears to date 1740-55 (fig. 10). It has four engaged Ionic pilasters that interrupt the cornice molding like the Doric pilasters of the earlier desks-and-bookcases (figs. 1, 7). The designer may have moved from the simpler to the more complex orders as he gained confidence in the carver he employed.[13]

The carved appliqué on the scrollboard of the desk-and-bookcase in figures 10 and 11 is virtually identical to the shell on a picture frame made by Boston carver John Welch (1711-1789) for John Singleton Copley's portrait of Nicholas Boylston (fig. 12). A successful artisan with a long, distinguished career (fl. 1732-1780), Welch was one of the most important tradesmen contracted by the Boston designer. He did all of the carving on the pieces illustrated in figures 10-25, 27-30, 40-47, and 51-53 and possibly on the two early desks-and-bookcases (figs. 1, 7) . Although there are minor differences between the carving on figures 1 and 7 and the later examples, a tradesman with a career as long as Welch's was bound to have an evolving style.[14]

Welch may have apprenticed with Boston carver George Robinson (1680-1737), whose granddaughter he married in 1735. In addition to carving numerous picture frames for Copley, Welch received several important public commissions including work for Brattle Street Church (demolished). In 1750 he received £377 for architectural carving on the rebuilt Massachusetts State House. His work included a carved lion and unicorn for the gable end of the east facade and Corinthian capitals for the pilasters flanking the balcony door (figs. 13, 14).[15]

Welch's long-term association with the Boston furniture designer is confirmed by the carving on an extraordinary desk-and-bookcase (fig. 15) probably originally owned by Boston goldsmith John Allen (1671-1760). An incised inscription on the top board of the desk -"John Allen his desk . . . made for"-nearly matches the signature on Allen's will drafted in 1736. John was the son of wealthy Boston landowner James Allen and partner of gold- and silversmith John Edwards.[16]

Comparison of the Corinthian capitals on the bookcase with those Welch carved for the State House leaves little doubt that they are by the same hand (figs. 14, 17). The Allen desk-and-bookcase is the most extensively carved piece attributed to this shop (figs. 15-19). The shells of the bookcase interior are carved rather than painted, and the facade is ornamented with urn-and-flame finials, festooned rosettes, and a scrollboard appliqué with flowers and acanthus leaves similar to those on the Boylston frame (figs. 12, 18). The flat surface of the prospect door echoes the shape of the bookcase mirrors, and the fascia over the door has an edge bead cut from solid wood and two relief carved cherubs on a punched ground. The winged cherubs probably were inspired by cast clock spandrels.

The carving on the feet suggests that Welch and the joiners had difficulty converting the designer's plans into three-dimensional forms (figs. 15, 19) . To be architecturally and visually correct, the ring and bellflowers should be centered beneath the columns of the desk; however, that would have required large feet whose profile would have been difficult to integrate into the blocked facade. Instead, the carver shifted the bellflowers toward the outer edge of the feet and inserted a partial leaf (which is discontinuous with the blocking and other carved elements) to occupy part of the space. The joiners and carver appear to have worked from an elevation drawing. The joiners had to reconcile the design with the engaged columns and blocking, and the carver had to accommodate both the designer and joiners. The edges of the feet have convex strapwork similar to the beads on the prospect door fasciae of desks in this group, whereas the ring-and-bellflower drops and central shell pendant, unique in this designer's work, are Kentian in conception.

Like the desk-and-bookcase in figure 1, the Allen example has expensive brass, large shaped mirrors, and is made of exotic woods. The backboards and dividers of the bookcase are sabicu, a tropical hardwood referred to as "horseflesh" in the eighteenth century. The drawer sides and backs are red cedar. In true baroque fashion, the facade is interrupted in several areas: feet, base molding, drawers, ¾-engaged columns of the desk, and engaged pilasters and cornice of the bookcase. The use of three pilasters is an improvement over the four-pilaster plan. Although the outer pilasters are architecturally integrated into the cornice, the earlier use of two center pilasters was redundant, because only one is required as a spring post for the door arches and as a visual support for the appliqué. To make the change, the joiner reduced the width of the inner stile of the left door and positioned the pilaster of the right door to lap over it. This became the accepted format from the mid-1740s on. The seven examples of the Corinthian order make this desk-and-bookcase one of the most Palladian case pieces from colonial America.[17]

The desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 20 represents a simplification and clarification of several design and ornamental details introduced in the Allen example (fig. 15) and demonstrates this designer's and the shop's ability to produce thoroughly composed, distinctive furniture forms. Wood rather than mirrored doors freed the dimensions of the bookcase and allowed the designer to make the piece more vertical. Most Vauxhall plates exported to the colonies were pre-manufactured and sold by merchants and looking glass makers rather than being custom-ordered by cabinetmakers. On bookcases with mirrored doors, the dimensions of the plates, which generally came in standard sizes, dictated the approximate height and width of the upper case and thus, the width of the desk. Because writing heights of desks were relatively standardized, the overall dimensions of a desk-and-bookcase with mirrors was determined largely by the plate dimensions. The maker could vary its proportions only by adjusting the widths of the door stiles and the height of the scrollboard. Without glass, a bookcase could be narrower and proportionally taller. The designer further emphasized the verticality of the bookcase by reducing the width of the engaged pilasters (specifying five flutes rather than seven as on figure 15) and by centering the carving on the vertical axis.

Like Kent and Batty Langley, this Boston-based designer occasionally employed late-baroque details to solve problems he faced in applying classical architectural conventions to furniture design. The two inherent problems of blockfront design in desks-and-bookcases-the transition from the bottom of the blocking to the floor and from the top of the blocking to the pediment-may never have been resolved with more success than on the desk-and-bookcase in figure 20. Gadrooned ball feet, like those of figure 20, are baroque details used by early-eighteenth-century designers such as Daniel Marot (fig. 31) and by Palladian designer-architects during the 1740s. They completely resolve the problems encountered with the blocked bracket feet of the Allen desk and make a bold transition from the engaged pilasters to the floor (fig. 21). The designer called for Doric pilasters on the corners of the desk and Corinthian pilasters on the bookcase, a use consistent with the superimposed orders of classical architecture (figs. 20, 21). Coped and molded sections of the pilaster capitals originally formed the faces of the lid supports.[18]

The design of the bookcase interior is typical of later pieces from the shop (fig. 22). The arches have gilt trompe l'oeil shells with acanthus leaves and small lion heads at the bottom (fig. 23) . A document drawer from the desk interior (figs. 24, 25) has a list of sums in pounds and shillings and the inscription, "Long[?] (L) 42-10 up to March 25th 51." Under this inscription is a profile sketch of a male head with a Roman nose, curly hair, and almond-shaped eyes. This facile drawing, which resembles a head from antiquity, may have been executed by the japanner or by the designer if he provided drawings of the shells for the japanner. In execution, it is closely related to the lion heads on the shells (figs. 23, 25) . If the same artist was responsible for both, as seems likely, then the "51" in the inscription is the date of the desk's construction—1751. The shells inside the bookcase are virtually identical to those in figure 11 and similar to the shell on the drawer of a Boston high chest from another cabinet shop (fig. 26), indicating that the japanner worked as a contractor. This anonymous japanner worked for the designer from at least 1750 to 1755 and possibly as much as fifteen years earlier (figs. 1, 7).

The designer of this group of furniture also maintained a long-term association with a turner, although it is not known whether the latter was a contractor or a member of the shop. This man apparently made all of the turned finials and feet for every piece from this shop. His vocabulary of forms and handling of small torus moldings (which are somewhat pointed in profile) are distinctive. The inverted cup-shaped finials of the bookcase in figures 20 and 23, for example, are related to the foot turnings of the desk section (fig. 21) and the cup-shaped urns of other finials in the group (figs. 15, 27). Similar comparisons can be drawn between the columns in later desk interiors and finials.

A clock case originally owned by wealthy Boston merchant Col. Henry Bromfield is almost exactly contemporary with the preceding piece (fig. 27) . The case houses a movement by London clockmaker Thomas Hughes and is labeled, "This case made by George Glinn 1750 . . . it cost £10 lawf. money." Although the inscription clearly is genuine, research has failed to find a Boston cabinetmaker named George Glum. Possibly the most remarkable achievement of this designer/shop and Welch, the case is a mid-eighteenth-century Boston form elevated by the conventions of classical architecture. The base and waist are like a building facade with corner plinths and pilasters, and the hood is reminiscent of eighteenthcentury temples and garden follies.[19]

The cove and ovolo base molding and pilaster base moldings of the clock case match those of the preceding piece (figs. 21, 29). The pilasters of these pieces also have corners molded with the same ovolo scratch stock cutter. On the clock case, the pilasters have four flutes on the front and four on the side, whereas those of the desk have five on the front and three on the sides. The joiners who made the desk may have had a front elevation only and incorrectly executed the side elevations. On the clock the base molding, plinths, and pilasters rise from bilaterally symmetrical feet, so they had to be equal on the sides and front of the case. Although the capitals of the clock pilasters are missing, the dimensions of the space the originals occupied suggests that they were Corinthian. To make the transition to the hood (which does not have projecting corners like the cove molding beneath it), the joiners glued strips of wood to the upper edges of the cove recesses and returns to make the edges even with those of the corners (fig. 28).

The joiners used many other techniques that diverge from normal Boston practice. After working down the interior surface of the waist door, they cut the molded edge from the solid wood by reversing the scratch stock cutter they used for the arch above the dial. Then they attached the door with finialed butt hinges similar to those used for bookcase doors rather than conventional clock-door hinges. They made the sarcophagus top in three sections: large cove, large ovolo, and small cove beneath the ovolo (fig. 28). The top board is molded on the front and side edges and nailed. Marks of the original center plinth on the top board indicate that the plinth was flanked by scrolled brackets (probably carved). To allow the bell to ring clearly, the joiners cut through the scrollboard behind the arch fret and spandrel appliqués and covered the openings with crimson silk. The original paper pattern is still glued to the back of the fret .[20] They hinged the hood door to an applied beveled strip (slightly thicker than the door) that extends behind the colonette on the right. The corresponding strip on the left houses the door and has a mortise to accept the bolt from the lock. Instead of coping the molding on the inside of this door frame, they mitered it at the corners. They rabbeted the dial skirt to receive the clock dial, and made most of the skirt and the front base rail of the hood of a hardwood that appears to be courbaril. Possibly relegated to a secondary position because of its difficult woodworking properties, this wood may represent stock remaining from the courbaril desk-and-bookcase (fig. 1). This clock case is the only other piece of Boston furniture known with courbaril as a primary or secondary wood.

The winged paw feet are remarkable in design and execution and unprecedented in the history of American furniture (fig. 29). The joiners or carver (if fabricated in his shop) constructed them like bracket feet: the grain runs horizontally, and they are mitered at the corners (between the front toes). The feet are laminated for thickness where the toes of the paw and ball emerge from the ankle.[21] The case has only front feet; the backboard extends to the floor to support the case in the rear.

Welch must have felt comfortable with the design of the carving for the clock case, as his carving for it is so confident and fluid. Although he reverted to a rapid ground-covering style on the feathers, the muscular shoulders and tops of the wings, complex shape of the ankles, and powerful acanthus scrolls of the feet make them the most distinguished examples from mid-eighteenth-century Boston. The spandrel appliqués (fig. 30) have a playful elastic quality that differs from the bold naturalistic appliqués of figures 9 and 18. The leaves have delicate cabochons on their spines and are propelled by the strapwork intertwinings of the appliqués.

Although the exact working relationship between the Boston designer and Welch will probably never be known, it can be reconstructed partially by interpreting what is written in wood in the context of seventeenth and eighteenth-century furniture design. The feet of the clock are derived from late-seventeenth- and early-eighteenth-century examples like those drawn by Marot (figs. 29, 31). An apostle of the baroque court style in France, Marot also drew clock cases with complex interrupted facades, engaged fluted pilasters, and carved ball feet, details frequently used by this Boston designer. The designer probably furnished Welch with a sketch of the clock case and a full-size profile drawing of the feet. As a carver of large animals for ships (i.e., two sea horses, 7 ½” long for a ship) and public buildings (fig. 13), Welch was capable of producing anatomically accurate three-dimensional forms.[22]

The varying design of the finials on furniture in this group suggests that the designer drew them as well (fig. 28). The tradesmen who made the clock finials-Welch, the turner, and possibly a japanner or gilder collaborated to make what became the prototype of most later Boston urn-and-flame finials. The larger flames, shorter spires, and flaring urn cap (made of white pine for gilding) make the clock finials an improved restatement of those on the Allen desk-and-bookcase (fig. 15) . They reflect the designer's and the shop's efforts to refine and perfect their work. The earlier flames have deep recesses, whereas those of the clock finials are comprised of three graceful twisted elements and are open at the top and pierced. The gadrooning and acanthus on the clock finials relate to the gadrooning on the feet of figure 21 and the acanthus on the finials of the Allen desk-and-bookcase (fig. 15) and figure 9.

A clock case reportedly made for loyalist Gilbert Deblois dates about 1751-1754 and has several subtle design improvements (figs. 27, 32). On the Bromfield case the plinths are wider than the space between them, which architecturally represents the wall on which they bear. To make the Deblois case more classically correct, the designer reduced the width of the plinths and left more space between the waist door and pilasters (figs. 32, 33). Because the plinths (and their base moldings) were too narrow to align with the wing feet, the designer enlarged the wings so they nearly meet in the center and increased the height of the base molding (compare figs. 27, 29, 32, 33). On the Deblois case, the molding above the dial arch is considerably larger than that of the Bromfield case and it is capped by a small bevel that surrounds the outer plinths (fig. 34) . Had the sarcophagus survived, the large ovolo molding would have been on approximately the same vertical plane as the frieze-another subtle architectural refinement. The arch fret and spandrels of the Deblois case also are missing (fig. 34), but they probably resembled those of the Bromfield case (figs. 28, 30).[23]

The molding changes on the Deblois case required retooling planes and scratch stock cutters. It is almost inconceivable that the joiners would have made these subtle but troublesome alterations unless they were specified by the designer. No matter what changes the designer made, they invariably met with translation problems in the shop. The pilasters, for example, have five flutes on the front faces and four on the sides and their Corinthian capitals are noticeably off-center (figs. 32, 35) architectural flaws that would have exasperated anyone with this artist's drive for classical perfection.

The Corinthian capitals show Welch in a very literal mode, employing small tools to produce exact, minute detail (fig. 35). These capitals are miniature versions of those Welch carved for the Massachusetts State House in 1750 (fig. 14). The colonettes of the hood also have exquisite Corinthian capitals and inlet brass stop fluting.

Both the Bromfield and Deblois cases were made to house expensive London movements, whereas simpler cases by this designer/shop have Boston movements. Typical of these restrained, architectural pieces are the clock cases illustrated in figures 36-38. With its horizontally configured base section, figure 36 is stylistically the earliest and probably dates around 1740. Its design, construction, and hardware details are related to those of the Bromfield and Deblois cases (figs. 27, 32) and another with a movement by Samuel Bagnall (fig. 37). The latter is the Boston model that provided the basic framework for the architectural details and carving that distinguish the Bromfield and Deblois cases. With the exception of the base molding and one small element of the hood, every molding section on the Bromfield case and figure 37 is the same. The joiners also repeated most of the construction and hardware details on the two cases (figs. 27, 37), but minor structural inconsistencies help establish a chronology. On figure 37, the joiners sawed openings in the scrollboard behind the frieze and spandrels after joining the supporting stage of the hood with dovetails. They abandoned this technique on the Bromfield and Deblois cases, omitting the dovetails, which would have to be cut away.[24]

A japanned clock case (fig. 39), probably made for a movement by James Atkinson (fl. 1744-1756), shares several details with the preceding examples (figs. 27, 32, 36, 37), although it cannot be attributed to this Boston designer/shop with the same degree of certainty.[25] The top board of the japanned case has clear witness for an original center plinth with flanking brackets, as on the Bromfield case (fig. 27). The lower stage of the sarcophagus top has a chamfered element like that of figures 28 and 34 and the hood door has mitered joints and small butt hinges. The door is hinged to a beveled strip that extends behind the front colonettes like all of the clock cases in the group. The corners of the dial skirt also have carved mason's miters like those of the case with the Bagnall movement (figs. 37, 38) .

The joiners used different planes and scratch stock cutters to cut the base moldings of the japanned case and the cases in figures 27-37; however, the basic shapes of the moldings are similar. The simplification of the moldings on the japanned case is logical considering that it is made of white pine, a soft wood less receptive to intricate, sharp detail. Many labor-intensive details, such as directly molded door edges, were unnecessary on cases with an elaborate (and semiopaque) decorative finish, so the joiners applied the molding on the waist door rather than cutting it from the solid as on figures 27, 36, and 37 or nailing it into a rabbet as on the door of the Deblois case (fig. 32).

A japanned case in the Henry Ford Museum and one advertised in Antiques appear from photographs to be nearly identical to figure 39, although their hoods lost all of the structure above their arched cornices. The basic design of these cases undoubtedly derives from figures 36 and 37, and the structural interrelationships suggest that at least some of the same tradesmen were involved in all of them.[26]

Unlike the preceding pieces, which have distinctly baroque details (blocked facades, elevated cornices, ball- and winged-paw feet), a desk-and-bookcase illustrated in Francis Clary Morse's Furniture of the Olden Time is almost entirely within the Palladian design mode (figs. 40, 41). On this piece, the designer added engaged Corinthian pilasters to the rear corners of the bookcase to integrate the front and sides and provide an appropriate theater for the figural ornaments of the pediment. According to its former owner, Reverend William Reed Huntington of Grace Church, New York, the side ornaments were "figures . . . carved from wood, of men at work at their trade of cabinet-maker." These figures and a central ornament were missing when Morse first published the piece in 1902. Assuming that the ornaments were original, which is very likely, the carving on this desk-and-bookcase may have surpassed the Allen example (fig. 15). Sketchy descriptions of Welch's sculptural carving for ships and public buildings (fig. 13), the feet of the Bromfield and Deblois clock cases (figs. 29, 33), and the knees of figure 53 offer the only context for imagining the figural carving on this remarkable desk- and- bookcase.[27]

The reverse ogee feet of the Huntington desk-and-bookcase have exquisitely modeled acanthus leaves and scrolls with bold convex volutes that literally quote elements on the picture frame by Welch (figs. 12, 42). The ground of the foot is punched but with more regimentation than that of figure 19. Although the leaves on the scroll feet have almost no interior detailing or shading (like those on Welch's frames), the design is very clear and easily comprehended (figs. 12, 42) . Scroll feet would have been extremely difficult to reconcile with a blocked facade, which probably explains why the piece has a straight front.

The desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 43 probably is the latest of the blockfronts in this group. Several construction details and minor aspects of its design differ from earlier blockfront desks-and-bookcases: the joiners made conventional blocked bracket feet, rounded the top corners of the blocking, and used fallboard supports that intrude on the top drawer. Although the stock preparation for the interior drawers of the desk-and-bookcase interiors is essentially the same, the construction varies from section to section, suggesting that at least two joiners were involved. The desk has a straight interior with a relatively simple prospect section. The door is flat rather than being blocked, but, like others in the group, it has an arched fascia with a beaded edge worked from the solid. The interior of the bookcase also has an arched fascia and fluted pilaster document drawers, echoing the design of the prospect section.

Welch carved the Corinthian capitals (including those in the desk interior), the scrollboard appliqué, and the flame finials, in the same basic style as the capitals and appliqués on the Bromfield and Deblois clock cases (figs. 27-29, 32-35). For the appliqués he used broad scrollwork to propel small sprays of acanthus leaves (compare figs. 30, 44) . Both sets of leaves have small cabochons on their spines and flutes applied in a similar manner. He also carved the upper elements of the turner's elegant finials-restatements of those made for figure 15-with pierced flames, almost the mirror image of those on the Bromfield clock (figs. 28, 43). Given the nature of the designer's and Welch's work, it is surprising that carved moldings, like the small ogee of the bookcase doors, were not used on the earlier pieces (fig. 44).

The preceding desk-and-bookcase and at least one other from the mid-1750s (fig. 45) suggest that this designer's attention to detail and his supervision of his workforce began to diminish during the mid-1750s. By 1755, some artisans associated with his shop were at least twenty years older than when their association began. Several journeymen must have come and gone between 1735 and 1755, eventually setting up their own shops or working for other cabinetmakers. Because these men continued to use many of the same designs and structural details they learned as journeymen, their work is difficult to separate from the original shop's as the following bombe desks-and-bookcases illustrate.

One of the earliest bombe desks-and-bookcases from Boston is by the designer and his shop (fig. 45). With the exception of the prospect door and its solid, beaded fascia, the interior of the desk is more consistent with mainstream Boston work than with the preceding examples (fig. 46) . The designer's shop either began to accept mainstream Boston styles or augmented its workforce with joiners who previously worked with more traditional cabinetmakers. The joiners who made the desk hollowed out the bombe sides by chopping them as though working curved house or ship timbers. The bookcase interior is similar to the Allen example (figs. 16, 47), but on the facade the designer added pulvinated or "swelled" friezes above the corner capitals-an architectural improvement over those of figure 43 and the trusses of the Huntington bookcase (compare figs. 41, 43, 47). Although Welch obviously carved the shells inside the bookcases of the Allen example and this bombe piece (figs. 16, 45), the leaves below the shells of the latter are completely undercut (fig. 47) .[28]

A bombe desk-and-bookcase signed by Benjamin Frothingham, dated 1753, shares several details with the Welch-carved bombe piece and other examples from the designer's shop (fig. 48). Nothing is known of Frothingham's early career except that he was born in 1734 and that his father, Benjamin, was a joiner. Since the younger Frothingham was only 18 or 19 when he signed the desk-and-bookcase, it is unlikely that he had the capital, skills, or patronage to make such an imposing piece, which raises the possibility that Frothingham was an apprentice or journeyman in the aforementioned designer's shop.[29]

The Corinthian pilasters and mahogany, red cedar, and cedrela interior fittings (similar to the preceding piece but without carved or gilt shells) readily suggest the bookcase as a product of this designer's shop. The construction of the desk interior is also similar to several of the preceding pieces (fig. 49). The interior drawers have thin red cedar frames and bottoms that are rabbeted to the front, sides, and back; the engaged columns are similar to those in the prospect section of the Huntington desk-and-bookcase (fig. 40); and the prospect door is concave, although it lacks the beaded arched fascia. The Joiners of the Frothingham-signed desk hollowed out its inner side surfaces more carefully than those of the preceding bombé desk-and-bookcase (fig. 45) but in the same method. They inlet the beads flanking the ends of the three bottom drawers of the desk into the front edges of the sides, which they left at full thickness. Then, they cut the rear edge of the beads and the corresponding edges of the case to match the outward swell of the facade. This is reminiscent of the exacting mentality of the joiners who developed the coped-base construction decades earlier. The element of the signed desk that most suggests involvement by the Boston designer is its molded plinth feet (figs. 48, 49). Although they occasionally occur on urban British pieces of the mid-eighteenth century, no other piece of furniture associated with Frothingham (and there are many) has plinth feet. The tall base molding, which provides a strong architectural resolution to the bombe sides, is also not typical of Frothingham's work. A bombé desk-and-bookcase illustrated in Morse's Furniture of the Olden Time has a similar base molding and feet (fig. 50). Whereas the construction of the latter departs more from the practices of the designer's shop, it too is very much in his style.[30]

It is almost inconceivable that the Boston designer and his shop only made case furniture. Although it is difficult to associate tables and chairs with case pieces because of inherent structural differences, an unusual concertina-action gaming table is probably by this shop (fig. 51) . The front legs were sawn like the center leg of a sofa rather than like the legs in standard cabriole construction. This resulted in small feet, the toes having to be configured within the square side dimensions instead of extending to the diagonal extremes of the stock. The lower rail of the table is dovetailed to white pine corner blocks that appear to be butt- or bridle-joined to the side rails. Because of the unusual frame construction, the top of the leg is outside the frame and relies on the cheeks of the turrets and top for support. The drawer is constructed like the blocked interior drawers of desks from this shop and the front rail beads are worked from the solid like the prospect door fasciae of nearly every desk-and-bookcase in the group. Although these structural relationships are not conclusive, they are sufficient for a tentative attribution to the Boston designer and his shop.

Welch was a mature carver when this table was made (1745-1755). The delicate convex strapwork (or bead) on the knee blocks (fig. 52) is similar to that on the feet of the 1738-1748 Allen desk-and-bookcase (fig. 19); however, the leaves on the knees and pendant are more closely related to those on the feet and spandrels of the Bromfield clock (figs. 29, 30) and on other pieces that he carved during the late 1740s and 1750s.

Welch carved the center leg of a pier table to almost the same pattern, but used a human face or mask as the central element (fig. 53). Kent and Langley frequently used human and animal heads on the knees of pier tables and other architectonic forms in England during the 1730s and 1740s. Considering the Boston designer's penchant for Palladian detail, it is reasonable to speculate that it was he who hired Welch to do the carving on this table.[31]

The aforementioned designer had a profound influence on Boston furniture styles from the mid-1730s to the 1780s. Two desks-and-bookcases from the late 1730s or 1740s demonstrate his influence on competing cabinet shops. The first (fig. 54) has four Corinthian pilasters, line inlay, shaped beveled mirrors, and an amphitheater desk interior with a concave blocked prospect door-details that occur in different forms on several of the desks-and-bookcases. The construction and techniques used, however, differ significantly from those of the designer's shop: the desk has thumb-nail molded drawers; on the top drawer the blocking is rounded; the fallboard supports intrude on the top drawer; the case is not cockbeaded; and the interior arches of the bookcase are decorated with inlaid fans rather than trompe 1'oeil or carved shells. The second desk-and-bookcase is probably from the same shop (fig. 55). The base molding is attached to the bottom board with a large dovetail, a standard practice in Boston around 1745-1780. In the production of sophisticated architectural forms, the cabinet shop that made figures 54 and 55 was the designer's most important rival; yet, the designs are almost completely derivative.

When Josiah Quincy purchased the Allen desk-and-bookcase (fig. 15) in 1778, the piece was over thirty years old, but it was stylish enough to satisfy one of Boston's wealthiest and most cosmopolitan citizens. In fact, most blockfront and bombé desks-and-bookcases made in Boston during the 1760–1780 period owe much to this designer. He and his workforce were responsible for the most varied, innovative furniture from eighteenth-century Boston. That city's cabinetmakers certainly made great furniture in the eras that followed, but this designer's spirit of exploration and adventure were unsurpassed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article, the author thanks Gavin Ashworth, Luke Beckerdite, Michael Brown, Ned Cooke, Robert Fileti, Bill Finch, Elizabeth Gombosi, Anne Haley, John Hays, Brock Jobe, Leslie Keno, Joe Kindig, III, Gregory Landrey Deanne Levinson, Frank Levy, Margaret Lichter, Joe Lionetti, Linda Lott, Anndora Morginson, Milo Naeve, Clark Pierce, John Pine, Michael Podmaniczky, Albert Sack, Harold Sack, Gail Serfaty, Laura Sprague, Laurie Stein, Jayne Stokes, Barbara Ward, Gerald Ward, and Philip Zimmerman.

Two years later the vestry sought his advice on building a gallery around the church (Sinclair Hitchings, "The Musical Pursuits of William Price and Thomas Johnston," Music in Colonial Massachusetts, Vol. II-Music in Homes and in Churches [Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1985], p. 650). Price also is credited with the design and supervision of work on Christ Church (Babcock, The Versatile Mr. Price, p. 6o). On April 1, 1737, he submitted a bill to the Wardens:

| To projecting and drawing a draft of ye

Organ to directing ye workmen in making it to drawing 6 large pannels of Cut Work to ditto 6 smaller |

1.10.0 5.0.0 2.0.0 1.0.0 |

Nine years later he submitted a bill for designing the steeple of Christ Church. He probably also designed the pulpit and interior furnishings (Hitchings, "Musical Pursuits," p. 650).

Eighteenth-century architects, such as William Kent and William Buckland, frequently designed furniture, and the great European designers were usually enthusiastic about designing objects for almost any trade (Wilson, William Kent Architect. Luke Beckerdite, "William Buckland and William Bernard Sears: The Designer and the Carver" and "William Buckland Reconsidered: Architectural Carving in Chesapeake Maryland, 1771–1774," Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 8, no. 2 [Nov. 1982] : I-88).

Antiques 52, no. 6 (Dec. 1947): 445. I have not examined this desk-and-bookcase; however, elements described in this and ensuing paragraphs make it clear that the bookcase was made by at least two of the tradesmen who worked for the Boston designer and his shop. The foot pattern, base molding profile, blocking, lid supports, fallboard, and prospect door of the desk are different from others in the group.

Welch received £8.8 for carving the Boylston frame (Morrison H. Heckscher and Leslie Greene Bowman, American Rococo, 1750-1775: Elegance in Ornament [New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992, p. 138). The layout and execution of the flame sections of the finials on fig. 9 resembles that of later finials with very strong ties to Welch (figs. 15, 28) The scrollboard appliqués of figs. 9 and 18 also are closely related. If Welch executed all of this carving, he moved from a totally naturalistic phase to one that occasionally hints at rococo. If Robinson (1680-1737) was Welch's master, and figs. 1 and 7 date before 1737, Robinson also could have been the carver. A master-apprentice relationship would explain the affinity with the later work.

Mabel M. Swan, "Boston's Carvers and Joiners, Part I," Antiques 53, no. 3 (March 1948): 199. Robinson's granddaughter was Sarah Barrington (Myrna Kaye "Eighteenth Century Boston Furniture Craftsmen," in Boston Furniture, p. 301). For more on Welch and carving attributed to him, see Barbara M. Ward and Gerald W. R. Ward, "The Makers of Copley's Picture Frames: A Clue," Old-Time New England 67 (Summer-Fall 1976): 16-20; Luke Beckerdite, "Carving Practices in Eighteenth-Century Boston," in Brock Jobe, ed., New England Furniture: Essays in Memory of Benno Farman (Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1987), pp. 123-62; Morrison H. Heckscher, American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Vol. II-the Late Colonial Period: Queen Anne and Chippendale Styles (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art and Random House, 1985), p. 331; and Heckscher and Bowman, American Rococo, p. 138. The author thanks Robert Mussey and Anne Haley for information on Welch's carving for Brattle Street Church. Beckerdite, "Carving Practices," pp. 143-47.

For related feet in Marot's work, see White, Pictorial History, pp. 438, 443, and Reimer Baarsen, Gervase Jackson-Stops, Phillip M. Johnston, and Elaine Evans Dee, Courts and Colonies: The William and-Mary Style in Holland, England, and America (New York: Cooper Hewitt Museum, 1988), pls. 4, 41. Beckerdite, "Carving Practices," pp. 143-44.

The Ford Museum clock is illustrated in Helen Comstock, American Furniture: Seventeenth, Eighteenth, and Nineteenth Century Styles (New York: Viking Press, 1962), p. 187. For a discussion of the japanning on this case and the Atkinson case, see Dean A. Fales, Jr., "Boston Japanned Furniture," in Boston Furniture, pp. 51, 54. G.K.S. Bush advertisement, Antiques 135, no. 5 (May 1989): 1002-3. This clock has a replaced superstructure above the cornice arch.