Jar, attributed to Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This vessel is decorated with three cobalt-blue watch-spring designs on the front and back, as well as cobalt-blue rings at the base of each handle and cobalt-blue paired watch springs adjacent to the lower end of both vertically oriented handles.

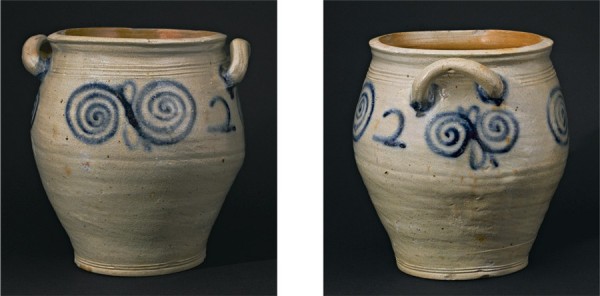

Jar, attributed to Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11 1/4". Mark: inscribed in cobalt blue on each side, “2” (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This vessel’s decorative elements are paired cobalt-blue watch-spring designs on the front, back, and below the handles, plus blue rings at the base of each handle.

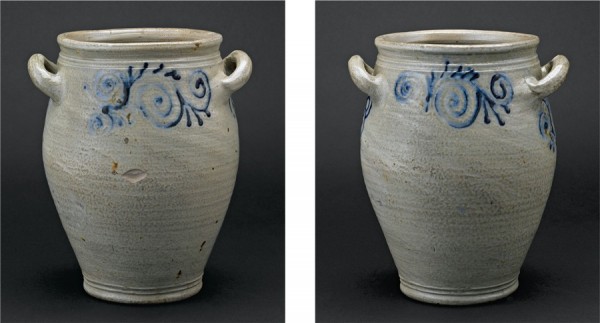

Jar, Kemple pottery, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, ca. 1746–1790s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11". (Courtesy, MCHA, Gift of Mrs. J. Amory Haskell; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The attribution is based on the cobalt-blue cogged watch-spring decoration on sherds found at the Kemple pottery site.

Jar, attributed to Kemple pottery, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, ca. 1746–1790s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9 3/4". (Courtesy, Marshall P. Blankarn Purchasing Fund, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The attribution is based on the similarity to the Sim notebook drawing on the left in fig. 53.

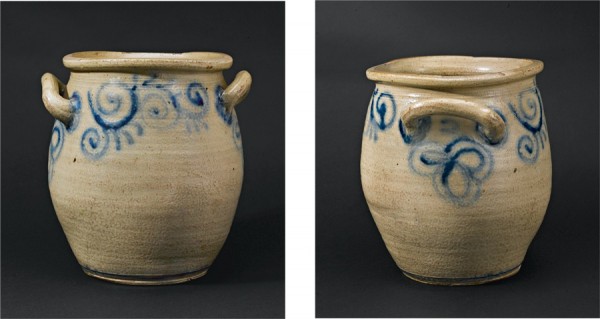

Jar, attributed to Kemple pottery, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, ca. 1746–1790s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Cogged watch-spring motifs adorn both sides, and there are three concentric ovals under each handle. The design below each handle is not found among the examined sherds.

Jar, attributed to Kemple pottery, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, ca. 1746–1790s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14". Mark: inscribed in cobalt blue, “4” (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This jar, which has exceptionally bold and unusually large loop handles, is decorated with several cobalt-blue elements: floral motifs and cogged watch-spring designs on both front and back; pomegranates accented with reddish brown cogs; circular cobalt-blue bands under the neck, at the base, and around all four handle bases; and a paired pomegranate design below each handle. Manganese or iron glaze accentuates the cogs, stems, and tips of the pomegranates.

Jar, attributed to Kemple pottery, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, ca. 1746–1790s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12 3/4". Mark: inscribed in cobalt blue, “2” (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This vessel has vertical handles and cobalt-blue decoration consisting of matching pomegranate designs (similar to the sherds illustrated in fig. 58) on the front and back, and a circular cobalt-blue band at the neck and base. Reddish brown cog accents on the shoulder are cobalt blue, similar to the jar illustrated in fig. 6.

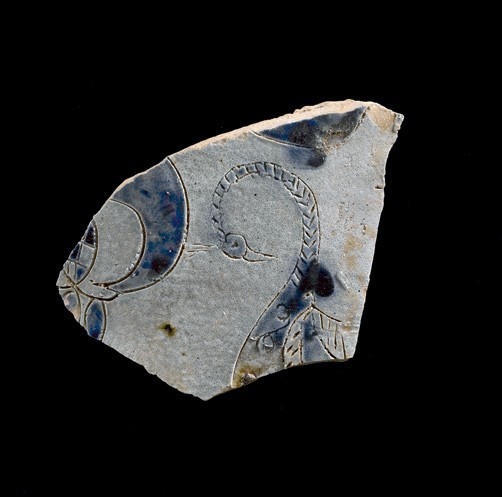

Jar fragment, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) A typical example of Morgan’s cobalt-blue watch-spring motif.

Jug fragment, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chamber pot, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6". (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, Marshall P. Blankam Purchasing Fund, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The decoration includes triangular dotted patterns.

Chamber pot, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6". (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, Marshall P. Blankam Purchasing Fund, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) One side of the chamber pot is decorated with a cobalt-blue, triple watch-spring design surmounted by a dot pattern; the other shows a floral motif emerging from a spiral.

Jug fragment, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, NJSM; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The fragment with triangular patterns of dots has two large spirals touching each other with a central foliate design rising above and between them. Below the handle is a circular dotted decoration.

Jar fragment, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Museum Purchase/Gift of Mrs. Robert J. Sim, CH174.112, NJSM; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The decoration on this sherd is a triple spiral from which a branching foliate motif emerges. A jar attributed to Morgan, currently in the Thomas Warne Museum, Old Bridge, New Jersey, has a similar triple spiral on one side and a quadruple spiral on the other side.

Jar fragment, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Depicted is a finely incised, cobalt-blue bird with a long neck and a crest, standing on a vine.

Sherd, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Drawn on this fragment is a finely incised, cobalt-blue bird with an extremely long feathered neck, a bill, and a crest.

Sherds, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These fragments show incised birds filled in with cobalt blue.

Sherd, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) At far right is a detail showing the partial image of a bird, incised and filled in with cobalt blue, above what might be another bird’s foot.

Sherd, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This fragment is decorated with an imaginatively drawn zebra; its body is decorated with diagonal cobalt-blue stripes alternating with blue dots.

Mug, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6 3/4". (Museum Purchase/ Gift of Mrs. Robert J. Sim, CH174.112, NJSM; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This restored mug, one of four known, shows a partially incised caricature of a human face, outlined in blue, adjacent to a stylized plant.

Mug, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 4 3/4". (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, Newark Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The cobalt-blue decoration on this restored mug is not as developed as that seen on other examples.

Mug, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Reproduced from a photograph in Sim and Clement, “The Cheesequake Potteries,” p. 123, fig. 3; Robert J. Sim Collection, NJSM.) This mug, whose location is unknown, is decorated with a geometric triangle-and-square pattern and a coiled spring at its handle.

Mug, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, Newark Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The design on this restored mug is a variant of that seen on the fragment illustrated in fig. 27.

Jug fragment, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) On one side of this fragment from a partially restored large jug is a fuchsia-like flower on a thorny branch; on the other are a brushed flower with petals and another fuchsia-like flower on thorny branches.

Jar fragment, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The leaves of the incised fuchsia-like flower on this fragment are filled in with cobalt blue.

Sherds, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The incised leaves shown here, one of which also has the incised figure of a bird, are filled in with cobalt blue.

Sherd, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) In addition to the incised, cobalt-blue leaves, this piece also has a partially incised flower at the top.

Jar fragment, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This example bears an elaborate slip-decorated flowerhead.

Sherd, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Reproduced from a photograph in Sim and Clement, “The Cheesequake Potteries,” p. 123, fig. 1; Robert J. Sim Collection, NJSM.) The sherd, known only from this published photograph, is illustrated with a fuchsia-like flower.

Plate fragment, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This partially mended plate is decorated with an elaborate floral motif in the center.

Bowl fragment, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The decoration of this partially reassembled bowl consists of vertical rows of cobalt-blue dots on the inside.

Sherd, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) A diamond-shaped pattern of cobalt-blue dots adorns this fragment from an unidentified form.

Chamber pot, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This large fragment of a chamber pot contains an elaborate triangular design of impressed circles, partially colored in cobalt blue, adjacent to a wavy design with dots and a simple spiral.

Sherd, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) On these assembled fragments is a pattern of cobalt-blue dots over illegible incised writing.

Sherd, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Museum Purchase/Gift of Mrs. Robert J. Sim, CH174.112, NJSM; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Surrounding the base of a broken handle are adjoining circular ellipses with a dot in the center of each. The cobalt blue was applied with a slip cup. The decoration on this vessel fragment is similar to that illustrated in fig. 11: both surround the terminal of the handle and have a fragment of a watch spring.

Sherd, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Museum Purchase/ Gift of Mrs. Robert J. Sim, CH174.112, NJSM; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The decoration on this vessel fragment is similar to that illustrated in fig. 34, both surrounding the terminal of the handle.

Sherd, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Arthur Clement Collection, Brooklyn Museum.) The central dots on these petals recall those found on the fragments illustrated in figs. 34, 35, and 41; the cobalt-blue decoration on this sherd, however, was applied with a brush.

Sherd, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The cobalt blue in this dotted matrix with wavy border was applied with a slip cup.

Sherds, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This cobalt-blue decoration depicts rows of wavy lines; in two of the examples the lines alternate with rows of dots. The center example is the only Morgan sherd to have an interior slip— a medium brown color beneath the shiny salt glaze.

Sherd, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy: New Jersey State Museum, NJDOT and FHWA (NJ Division); photo, Leslie Warwick.)

Sherd, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. Mark: inscribed “2” (Courtesy: New Jersey State Museum, NJDOT and FHWA (NJ Division); photo, Leslie Warwick.)

Sherd, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Museum Purchase/Gift of Mrs. Robert J. Sim, CH174.112, NJSM; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The cobalt-blue dot centered within each of what might be fish scales is close to the three-tiered fish-scale design illustrated in fig. 42.

Detail of the 3-2-1 fish-scale design illustrated in James S. Brown Jr., “Notes on New Jersey Stoneware Potteries before 1850,” p. 21, undated draft, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA.) The source of Brown’s illustration is unknown.

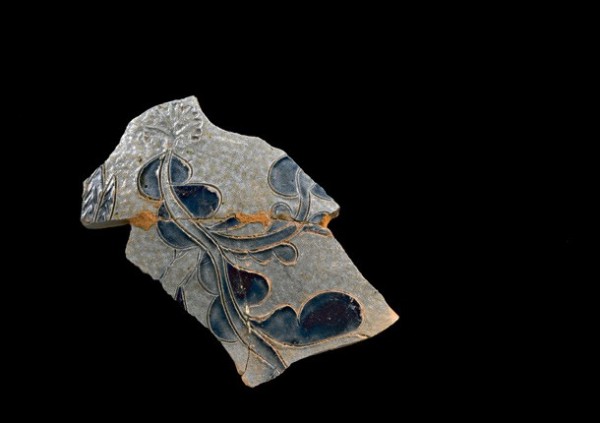

Sketch of the coggle pattern found on the first of two fragments recovered by Sim. The location of those sherds is not known.

Plate sherd, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The two sides of this partially reassembled deep plate rim are decorated with spirals and swirls.

Deep plate sherd, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Flask or bottle fragment, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. Mark: incised “S VD[in ligature] H” within a heart. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar sherds, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13 1/2". (Museum Purchase/Gift of Mrs. Robert J. Sim, CH174.112, NJSM; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These two fragments of this large jar bear a partial inscription: “. . . Danniel Holmes / . . . September 23, 1775 / . . . mboy James Morgan / & [M?] . . . .”

Sherd, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Arthur Clement Collection, Brooklyn Museum.)

Jug fragment, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. Mark: inscribed in cobalt blue, “Liberty / 1776” (Museum Purchase/Gift of Mrs. Robert J. Sim, CH174.112, NJSM; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This large, partially reassembled jug bears a triangular dot pattern under the inscription and watch springs on both sides of the handle.

Chamber pot, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. Mark: inscribed “cpt [M]ay the 3 1776” (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, NJSM; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Sherd, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. Mark: impressed “1776” (see detail). (Courtesy, Arthur Clement Collection, Brooklyn Museum.)

Mug fragment, Morgan pottery, Cheesequake, New Jersey, 1775–1784. Salt-glazed stoneware. Mark: inscribed in cobalt blue, “1776” (Courtesy, Arthur Clement Collection, Brooklyn Museum; photo reproduced from Donald Blake Webster, Decorated Stoneware Pottery of North America [Rutland, Vt.: Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1971], p. 36, no. 16.)

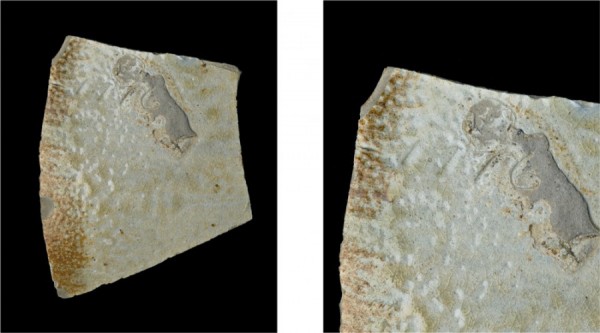

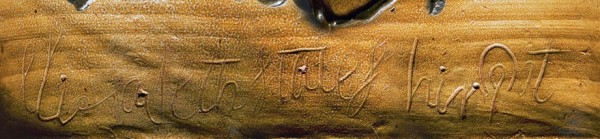

In a letter to James Brown Jr., Sim included sketches of the decoration on the Kemple sherds he found at Ringoes. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Leslie Warwick.)

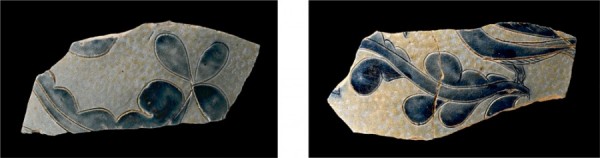

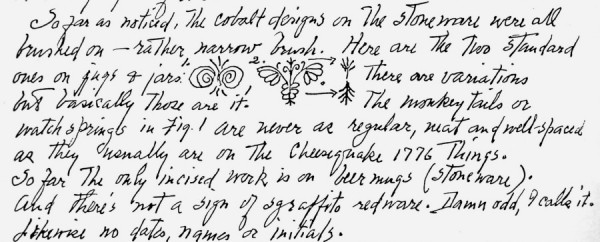

Plate fragments, Kemple pottery site, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, ca. 1746–1790s. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

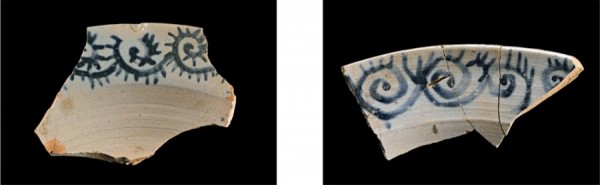

Jar fragment, Kemple pottery site, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, ca. 1746–1790s. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The incised cobalt-blue bands on this fragment are also seen on the fragment illustrated in fig. 56. Both show what appears to be part of a well-developed floral-like design with filamentous extensions.

Jar fragment, Kemple pottery site, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, ca. 1746–1790s. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, NJSM; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Similar to the sherd illustrated in fig. 55, this piece has incised cobalt-blue bands and a well-developed floral-like design.

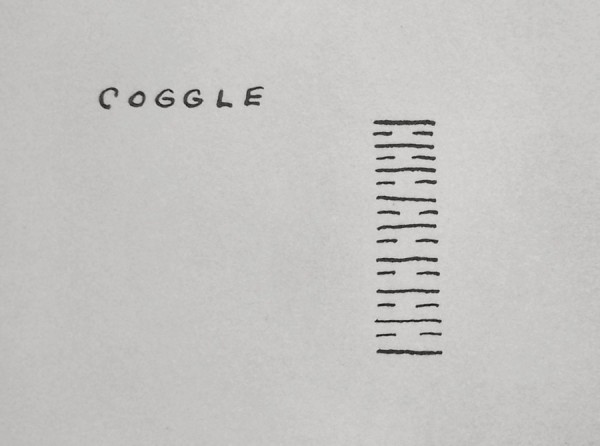

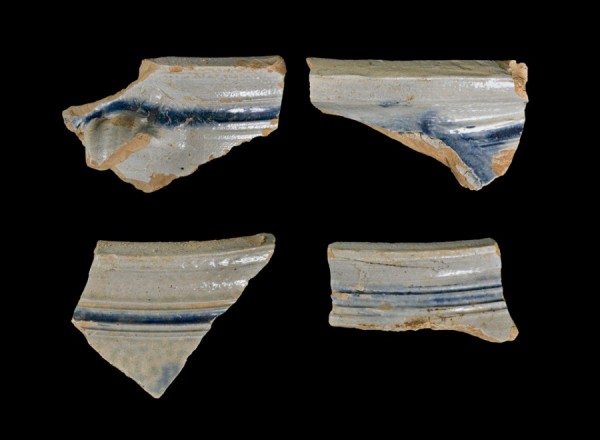

Jar fragments, Kemple pottery site, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, ca. 1746–1790s. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, NJSM; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

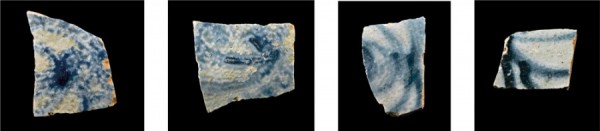

Jar fragments, Kemple pottery site, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, ca. 1746–1790s. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, NJSM; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These four small fragments have partial images of pomegranates.

One of the pomegranate-decorated sherds recovered from the Kemple pottery site (illustrated in fig. 58) photographically superimposed on the attributed Kemple stoneware jar illustrated in fig. 6. (Photo composite, Gavin Ashworth.)

One of the pomegranate-decorated sherds recovered from the Kemple pottery site (illustrated in fig. 58) photographically superimposed on the attributed Kemple stoneware jar illustrated in fig. 7. (Photo composite, Gavin Ashworth.)

Sherds, Kemple pottery site, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, ca. 1746–1790s. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Museum Purchase/Gift of Mrs. Robert J. Sim, CH174.112, NJSM; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

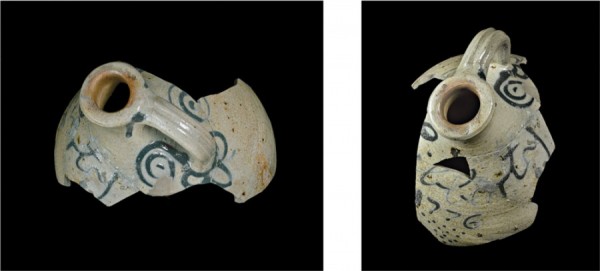

Mug fragment, Kemple pottery site, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, ca. 1746–1790s. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) One of two sherds (see also fig. 63) closely related to pottery made in the Westerwald region of Germany, this shows elaborate decoration, with an incised blue checkerboard pattern with three cobalt-blue bands and multiple tooled circular incised bands.

Square or rectangular bottle fragment, Kemple pottery site, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, ca. 1746–1790s. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) As does that illustrated in fig. 62, this fragment recalls pottery made in the Westerwald. The decoration here is an incised leafed branch on one side and a checkerboard pattern filled in with cobalt blue.

Probable teapot fragment, Kemple pottery site, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, ca. 1746–1790s. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Museum Purchase/Gift of Mrs. Robert J. Sim, CH174.112, NJSM; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This fragment showing incised flower decoration is similar to a sherd Sim found at the Morgan pottery site (see fig. 24).

Spouted vessel, attributed to Adam States, Greenwich, Connecticut, ca. 1745. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 4 1/2", W. 5 3/4". Mark: incised above base, “Elizabeth States her Pot”; below left rim, “E I S A S [illegible]” (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This vessel is missing its handle but retains its slightly flared spout.

Details of the inscriptions on the vessel illustrated in fig. 65.

Two of the earliest makers of salt-glazed stoneware in America operated in New Jersey during the eighteenth century. Captain James Morgan managed a pottery in Cheesequake, Middlesex County, from about 1775 to 1784 (figs. 1, 2). The Kemple family of potters worked in Ringoes, Amwell Township, Hunterdon County, beginning in early 1746 until the 1790s (figs. 3-7). Until now, the extent of our knowledge about these potters was based on excavations and related research conducted by Robert James Sim (1881–1955) starting in the early 1940s and, after 1949, in collaboration with James S. Brown Jr.

Robert Sim of Yardville Heights, New Jersey, was an amateur archaeologist and collector of stoneware, redware, and other ceramics, and a pioneer in discovering early New Jersey potteries. He held positions as an entomologist, natural history artist, photographer, researcher, historian, and author. He worked continuously as a plant industry inspector with the New Jersey Department of Agriculture from 1924 until his death, except for five years doing similar work for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. During his working career, he was also a scientific illustrator for the federal Bureau of Entomology and the state Agency of Entomology, Plant Industry, and Biological Survey.[1] He had broad interests, writing booklets and articles, and at the time of his death he had been preparing a publication on early New Jersey grist mills and a major text on early pottery in New Jersey.

Two of Sim’s most important archaeological accomplishments were identifying the Cheesequake pottery sites of Captain James Morgan and the later operation of Thomas Warne and Joshua Letts.[2] Working with Arthur W. Clement of the Brooklyn Museum, Sim was able to locate Morgan’s pottery. Clement was responsible for discovering documentary evidence of this operation and in 1947 curated a major exhibition, “The Pottery and Porcelain of New Jersey, 1688–1900,” at the Newark Museum. In 1955 Sim and Brown prepared the research notes for New Jersey Stoneware, the exhibition catalog accompanying the show of May 21–June 21, 1955, mounted by the Monmouth County Historical Association in Freehold. This was followed in 1958 by a major exhibition at the New Jersey State Museum of about 375 seventeenth- to twentieth-century ceramic pieces and potting utensils from New Jersey, including many examples of New Jersey stoneware from the Sim estate as well as sherds from his excavations.[3]

James S. Brown Jr. also had an interest in early New Jersey potteries and shared a close working and personal relationship with Robert Sim from 1949 until Sim’s death in 1955. Brown researched deeds and other records and was an amateur archaeologist and collector of stoneware. As an associate editor at the Asbury Park Press he wrote many columns about antiquing and the discoveries he and Sim had made. Their extensive correspondence in the Archives of the Monmouth County Historical Association conveys their intense pleasure in and enthusiasm for their research and archaeological findings at the pottery sites of Ringoes, Cheesequake, Herbertsville, Old Bridge, and others. Importantly, their letters to each other included extensive descriptions of kiln sites, sherds, identifications, and relationships among the potteries.

The Kemple pottery was one of the earliest and longest-running potteries in New Jersey, and there have been two archaeological investigations of its site. The first was by Sim and Brown during the 1950s.[4] The second, in 1976, was by Brenda L. Springsted, whose research associated the Ringoes pottery with Johan Pieter Kempel, an immigrant from Neuwied, in the Westerwald region of Germany, as well as his son Philip and grandson Ontiel, as potters.[5] Analysis of the salt-glazed stoneware sherds from both archaeological studies revealed a number of forms, including ovoid jars or crocks with vertical and horizontal handles, jugs, flasks, small pots, bowls, beer mugs, spouted beer pitchers, thin-walled cups, deep porringers, lids, and kiln furniture. Earthenware fragments were also found. These utilitarian wares fulfilled the needs of the farmers and rural households in the community.

The research of Sim and Brown was considered the best available information for New Jersey stoneware scholars for many years but was not published. Therefore, by the end of a recent daylong symposium on early New York and New Jersey stoneware sponsored in 2004 by The Potteries of Trenton and the New Jersey Historical Society, it was apparent that more information was needed in order to attribute with certainty the unmarked vessels from the New Jersey potteries of Captain James Morgan and the Kemple family.[6]

The authors determined that an examination and publication in color of all the known sherds from these pottery sites was necessary, including those in the notable collections at several institutions: the Monmouth County Historical Association, Freehold, New Jersey (MCHA); the New Jersey State Museum (NJSM); the Newark Museum; the Brooklyn Museum; the Smithsonian National Museum of American History; the Trenton storage facility of the New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT), which contains the sherds excavated from the Morgan pottery site in 1997 by Hunter Research, Inc.; and the archives and ceramics at the Thomas Warne Museum, Old Bridge Township. In the autumn of 2004 Joseph W. Hammond, a former MCHA director, clarified and categorized the association’s large Robert J. Sim collection of sherds from the Morgan pottery site. The MCHA and NJSM collections also contain a small number of sherds from the Kemple pottery site (found by Sim and Brown) that were donated by James S. Brown Jr. In addition to our study of these collections, we also reviewed the papers in the extensive archives of both Sim and Brown at the MCHA and the NJSM.

This paper presents the results of our new research and a reevaluation of the previous descriptions—published and unpublished—of the Morgan and Kemple sherds. We present newly attributed vessels based on the sherds and a review of the backgrounds of Captain James Morgan and the Johan Pieter Kemple family, as well as their possible relationships to New York City potters Remmey and Crolius. In addition, the historical context for the immigration of the German potters Kemple, Remmey, and Crolius to the colonies is examined. We conclude with a discussion of the styles and designs of the Morgan and Kemple potteries, along with those of Adam States.

Migration from the Westerwald

The Thirty Years’ War in Europe (1618–1648) devastated the German countryside and its people, reducing the population by as much as thirty percent. To escape persecution, large numbers of inhabitants fled to the Westerwald region, which at the time was peaceful and a refuge for potters from Sieburg and Raeren. The influx of residents caused the pottery industry in the towns of Hohr, Grenzau, and Grenzhausen to grow. (Today this site is in the Westerwald area of Kannenbackerland, near Koblenz. The potters worked in or near the current city of Hohr-Grenzhousen, a major stoneware pottery area.) After the Thirty Years’ War ended, the number of potters in the region grew rapidly, from fourteen in Hohr in 1630 to twenty-four in 1660 and more than forty in 1683. By the early eighteenth century the number of guild members had risen to about six hundred.[7]

Despite this apparent prosperity, there was stiff competition from the tin-glazed earthenware and household metalware industries during the eighteenth century. More important, Germans were again under siege due to the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), during which King Louis XIV of France, a Catholic, and other countries invaded Protestant sections of Germany for dynastic aggrandizement, territorial ambitions, and religious dominance. To escape persecution this time, Protestants and other Germans—in one of the country’s major emigrations—began to leave for the English colonies in America.[8] In 1718 Johann Wilhelm Crolius, formerly of the Westerwald, emigrated from Eifel to New York.[9]

Dr. Franz Baaden, who has written extensively on the Westerwald pottery industry, adds insight into further reasons for German potters to emigrate to America:

In the 18th Century . . . a considerable number of [potters in the Westerwald region] decided to leave for other locations in Germany or abroad to establish new potteries. Conditions for new settlements outside Germany were especially favorable, as the rulers of these countries granted special privileges to the potters. This was important because another reason for leaving the Westerwald was the potters’ guild regulation which permitted only the first-born son in the family to become a master potter. Younger sons were not willing to be content with a subservient position under their older brothers, preferring to leave for foreign lands without such restrictions.[10]

It was in this period that two other potters, also from the Westerwald region, emigrated: John Remmey, in 1731, and Johan Pieter Kemple, by 1739. They probably came indirectly, via Holland and/or England to America. It is not known why Crolius, Remmey, and Kemple left their homelands; their emigration to the colonies may have been based in whole or in part on a fear of war—given Germany’s violent history—a search for greater freedom, religious toleration, economic or social opportunities, or a desire to shape their own future. In contrast to many other German immigrants, these three potters must have been reasonably prosperous to have met the expenses of the voyage and to have been able to acquire land and establish their potteries shortly after their arrival. The salt-glazed stoneware they made was in the tradition of Westerwald’s Hohr-Grenzhausen area, where they were born and had trained and potted.

Captain James Morgan (1734–1784)

In 1710 Captain James Morgan’s grandfather, Charles Morgan of Perth Amboy, New Jersey, bought five hundred acres of land in Cheesequake, near South Amboy, New Jersey, which included large banks of high-quality stoneware clay.[11] Captain Morgan’s father, Charles Morgan Jr., bought additional, adjoining land in 1730, which he bequeathed to his youngest three sons, William, Daniel, and James. In 1764 William and Daniel deeded their portions to James.[12] James Morgan had an extensive Revolutionary War record, serving in the 2nd battalion of the Middlesex (New Jersey) Militia under the command of Colonel John Neilson between September 21, 1776, and April 1780. He rose to the rank of captain and commanded a company of twenty-five to fifty men:[13]

| Date of service | Location in New Jersey | Comments | ||||

| 9/21–10/17/1776 | Newark and Elizabeth | |||||

| 2/1–3/3/1777 | Cranberry | |||||

| Summer 1777 | Long Branch | Captured the brigantine William and Anne | ||||

| 9/8–12/7/1777 | South Amboy, Raritan River and Bay | |||||

| 1/5–10/27/1778 | South Amboy, Raritan River and Bay | |||||

| 9/24–12/1/1779 | South Amboy and vicinity | 8/12/1779 British destroyed Morgan kilns | ||||

| 12/23/1779 | South Amboy | |||||

| 2–4/1780 | South Amboy and Spotswood | |||||

There is no evidence that Charles Morgan Jr. ever made pottery or that his son James was even a trained potter.[14] It is possible that Captain Morgan sold his clay to other potteries, especially to New York City, but there are no records to confirm this; in any event, shipment would have been highly improbable for a rebel officer, since New York Harbor was controlled by the British fleet from 1775 to 1783 and New York City was occupied by the British. Captain Morgan also owned a tavern in South Amboy known as Morgan House, or the Cheesequake Hotel, a site for official and social functions.[15] Records show that he paid taxes on the tavern in 1778 but sold it by 1780, when he had more than “£1,500 pounds loaned at interest.” His 1778 and 1780 tax records show that he owned 300 acres of land, 2–4 horses, 8–9 cattle, and 4 pigs, making him a farmer as well.[16]

Morgan’s association with pottery making is based on the pottery dump that Sim and Clement found on this property. They recovered fragments dated as early as 1775. Because Morgan was involved in a variety of business interests, he probably was not a potter himself but hired others to work for him. Master stoneware potters and journeymen were available from the contemporary potteries of the Crolius and Remmey families in Manhattan, and from recent German Westerwald immigrants going initially to Cheesequake. One possible potter at the Morgan Pottery, suggested by James S. Brown Jr., is Mathias Staats (later anglicized to States), the eldest son of potter Adam States of Greenwich, Connecticut.[17] The States family tradition is that Adam and his brothers Peter and Mathias came from Holland, and that Adam or Mathias worked with Captain Morgan’s son, James Morgan Jr. (1756–1822; later referred to as General Morgan based on his militia rank as a major general).[18] There is no record of Mathias as Adam States’s brother but there is as Adam’s son, and it is highly probable that he also worked with Captain Morgan.

Mathias was born in Pennsylvania in 1748 to Adam States and Elizabeth Giltenaar (or Geldener).[19] He served in Captain Morgan’s company in the 2nd regiment of the Middlesex Militia in February and October 1777 and January–February 1778 with the rank of sergeant. In March 1777 Mathias served under Captain Williamson, although as a private. Captain Morgan showed his confidence in Mathias by promoting him back to sergeant.[20] As the eldest son of a master potter, it is likely Mathias was also a potter. He is recorded as paying taxes on one hundred acres in South Amboy from 1780 to 1786, at least two years after Captain Morgan’s death, although in 1790, 1810, and 1830 U.S. Census records he appears as living in Fairfield, Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania.[21] He seems to have left the South Amboy area in 1786. Having served closely with Captain Morgan during the Revolution, Mathias could also have potted for him, and he probably potted for General James Morgan Jr. after Captain Morgan’s death. If this is true, States might have played a role in incorporating the watch-spring decorations of his father, Adam States, at the Morgan pottery (see fig. 65).

William Crolius (1753–1830), the eldest son of Manhattan potter John Crolius Sr. and brother of John and Clarkson Crolius, also worked at the Morgan pottery. He served in the Revolution in the Commissary Department and was present at the battles of Long Island, White Plains, and Monmouth.[22] He was living in South Amboy as early as 1786, as shown by his name in the South Amboy tax lists, and owned a house and lot. By 1788 he owned a horse and cow but probably returned to Manhattan by 1790, as he is not listed in the South Amboy tax lists after 1789. He appears as a potter in the Manhattan directories from 1793 to 1826, and reappears, briefly, in the South Amboy area in 1797.[23] Branin suggests that Crolius’s pottery style would have differed somewhat from the decorative treatments that Mathias States was using, which could explain the two different Morgan pottery styles found by Sim and Clement: “The fragments in the eastern (and apparently older) side of the dump have slip decorations in bluish or blackish grey. Those from the western side have various brushed-on designs in bright deep blue, ranging from cobalt to nearly ultramarine.”[24]

Stoneware was made at the Morgan pottery site, at least by 1775 based on dated sherds recovered. A possible initial date is suggested by the mortgage James Morgan took out in November 1768 with Thomas Walton, a Manhattan merchant. For £393 Morgan mortgaged two parcels of land, one of 280 acres and the other of 23.81 acres. The Morgan pottery sherds found by Sim were from the smaller parcel.[25] Perhaps the mortgage was to fund the construction of a kiln, which would indicate a start of production in the early 1770s. The work undertaken by Hunter Research suggests Morgan’s pottery was established about 1770.[26] The pottery was severely damaged by British troops on August 8, 1779, according to a loss affidavit filed by his son, General James Morgan Jr.[27] It is believed that with the help of such potters as Mathias States and William Crolius, General Morgan managed the pottery after his father’s death in 1784. With Jacob Van Wickle and Branch Green, he formed James Morgan and Company, a stoneware manufactory in nearby Old Bridge that was advertised in 1805.[28]

Morgan Pottery Site Sherds Found by Sim

Of the many sherds recovered from the James Morgan pottery, those that are most typical have slip-trailed, cobalt-blue spiral or watch-spring motifs (figs. 8-13), a design that occurs on a variety of forms, including jars, jugs, and chamber pots. The watch-spring pattern occurs as a single motif or is combined with one or more to create elaborate decoration. An exception to the usual watch-spring design is the cogged spiral that appears on the shoulder of the vessel illustrated in figure 47.

While examining sherds in 1950 at the Ringoes Pottery site (not yet identified as Kemple’s Pottery) Sim wrote in his notebook, “Considering the resemblance to the Matey farm stoneware [Captain Morgan at Cheesequake] and that of Deacon Mead of Connecticut, it seems possible that the potter here was one of the Staats family.”[29] He recognized how the spiral design had a historical link to States (Staats) and subsequently to his apprentice Mead.

Among the most interesting and aesthetically significant finds from the Morgan pottery is a group of finely incised figural depictions (figs. 14-18). Five are of birds, drawn in a simplified naïve fashion; two have extremely long necks and three have crests. A fanciful, imaginatively drawn four-legged animal, probably a zebra, has its body embellished with diagonal cobalt-blue bands alternating with blue dots.

Four mugs are known from the site that also have incised decoration (figs. 19-22). One image on a restored mug shows a partially incised caricature of a human face, outlined in blue, adjacent to a stylized plant (see fig. 19). All of the mugs exhibit variations in the incised grooves and bands at their upper and lower portions. Some are filled in with cobalt blue.

A variety of floral and foliate decorative motifs is also found on a number of Morgan sherds (figs. 23-28). These were applied using both slip-trailed and incised techniques. The decoration occurs on large jugs and jars, but a remarkable small plate or dish has an elaborate floral decorative motif in its center (fig. 29). This plate form is highly unusual for American stoneware.

The use of slip-trailed dot designs is another diagnostic characteristic of the Morgan stoneware. Rows of closely spaced dots are used to create lines and patterns. This type of decoration occurs on a steep-sided bowl, a very atypical form in American stoneware of any period (fig. 30). Very elaborate patterns are noted using this technique of decoration (figs. 31-37).

Other decorative uses of cobalt slip decoration are hinted at by the Morgan sherds but defy specific classification. Cobalt-blue designs of slip-trailed wavy lines, one over the other, are found on three sherds, two of which have dots between the wavy lines (fig. 38). Archaeological excavation by Hunter Research recovered two noteworthy examples of Morgan stoneware. The first bears a spiderlike design, the only known example of this pattern (fig. 39). The second is a jar fragment (fig. 40) bearing a cobalt “2” very similar to the mark found on the jar illustrated in figure 2. Of note is a segmented flowerhead with dots inside the petals (fig. 27) and a variant incised design on a restored mug (fig. 22). An example of a small fish scale–like design with dots was found that might relate to one that Brown illustrated—a three-tiered fish-scale design whose whereabouts are unknown (figs. 41, 42).[30]

Sim also noted the use of coggle decorations at the Morgan pottery. Brown wrote: “Only two fragments of coggle decoration were found in the dig. One was a band about a half-inch wide made up of alternately one long and two short lines. This ran vertically up the side of what apparently was a small jug. The other was a rope-like band which twined around a piece from top to bottom.”[31] The first coggle pattern, which is sketched, is shown in figure 43. Two unusual plate or dish forms are decorated on their rims with cobalt spirals and swirls (figs. 44, 45). A unique find is a sherd with the incised letters “S VD[in ligature] H” within a heart (fig. 46).

Four very significant dated vessels were recovered from the Morgan site that provide a crucial chronological foundation for operation. There are two large fragments from a jar that bear a partial inscription, including the date September 23, 1775 (fig. 47).[32] This is the only vessel that has “James Morgan” written on it. On its shoulder is a very faint brushed cogged watch-spring design, which can also be found on another sherd (fig. 48).[33]

The only other dated pieces from the Captain Morgan pottery site that we found exhibit the historically important date 1776—either incised or brushed on the excavated sherds—in celebration of the Declaration of Independence. This reflected Morgan’s love of country as well as his role in the militia during the Revolutionary War. Morgan’s patriotic sentiments are conveyed on a large jug fragment inscribed “Liberty / 1776” above a triangular dot pattern with watch springs on both sides of the handle (fig. 49). A chamber pot with watch springs and a partially legible inscription that includes the year 1776 is shown in figure 50. Two small sherds in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum show an incised “1776” on one (fig. 51) and the same date applied in cobalt-blue slip on the other (fig. 52).

It should be noted that the cobalt-blue glaze on many of the sherds has a lustrous glasslike translucence, with an inner glow similar to a highly polished gemstone. This translucent cobalt decoration is mainly seen in late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century New York and New Jersey stoneware. In general, on later cobalt-blue–decorated stoneware the color may be vivid but it is opaque. The overall workmanship exhibited by the sherds and the decorative techniques employed suggest that the Morgan potters were highly skilled.[34]

The Kemple Family

Johan Pieter Kemple (also Kempel) was christened November 27, 1692, the second son (and eldest of two sons given the same name) of Christ Kemple and Anna Juliana Staaten, in Nordhofen, then part of the archbishopric of Wied in the present-day Westerwald region of Germany.[35] Kemple married in 1721 and, after his first wife died, remarried in 1723 in Germany. From these first two marriages he had six sons. He immigrated to Manhattan before 1739 with sons Philip, William, and Peter.[36] He married his third wife, Maria Clouer, in 1745 in the Reformed Dutch Church of New York. He is identified in the marriage record of the church as a widower from Neuwied, a town on the Rhine about six miles from Nordhofen and eight miles downstream from Koblenz, also on the Rhine.[37] In 1746, either Johan Pieter Kemple or his son Pieter Kemple witnessed the baptism of a daughter of potter Adam Staat (States) at the same church.[38]

In 1746 Johan Kemple purchased a tract of 245 acres from Samuel Johnson in Amwell Township, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, near the village of Ringoes.[39] In the deed Kemple is mentioned as a potter living in Amwell.[40] Hunterdon County was a popular destination for German and Dutch settlers, who by 1790 each represented twenty-five percent of the county’s population, second only to Bergen County, where forty percent of the population was Dutch and twenty percent German.[41] Ringoes had many German settlers from the Westerwald, including Johann Peter Rockefeller, who arrived in 1723 and from whom John D. Rockefeller was descended.[42] An adjacent forty-five acres was purchased by Kemple’s son Philip Campbell (Kemple) in 1750.[43] Johan Kemple died in 1761, and his will mentions “peter Kumbel poter.” He was survived by at least four sons—Philip, William, Peter, and Christian. Philip, the eldest, appears to have carried on the pottery, as his will in 1777 and inventory in 1778 list a potter’s mill and wheel, loads of clay, jugs, teapots, plates, pots, glazing tubs and “leadles,” and unfired earthenware. The ceramics were described as earthenware. Philip’s son, Ontiel, carried on the business until his death in 1798, at which time the pottery closed. His inventory included “salt and potts,” potter implements, and earthen- and stoneware.[44]

Since none of the Kemple stoneware is marked, it is necessary to attribute the stoneware to the Kemple family as a whole. Judging from the size of their property, the Kemples were farmers; making stoneware and earthenware was probably a part-time business. This is supported by the inventories of both Philip and Ontiel, which, in addition to the pottery implements and wares, list farm equipment and, in the case of Philip, corn, buckwheat, oats, and flax as well as livestock.[45]

A question we had after examining the pots and sherds attributed to Kemple was also expressed in a long, enthusiastic letter from Sim to Brown on his detailed findings of the now known pottery site: “My Jim!: . . . It’s all quite amazing. Where the hell did they get that clean stoneware clay? Cart it by ox team all the way from Cheesequake or find a local bed? The soil of that wheat field and vicinity is the characteristic dark red clay that’s pretty general in the Piedmont.”[46] Later Sim concluded that the potters at this site used the same local yellowish clay for all their redware and stoneware.[47] Richard Hunter, William Liebeknecht, and Michael Tomkins have suggested that the Kemples “possibly imported their clay from the Cheesequake area.”[48]

Ringoes is a rural inland community about thirty miles, as the crow flies, from the Morgan stoneware clay bank in Cheesequake, New Jersey. However, an important eighteenth-century road, Old York Road, passed through Ringoes to Raritan Landing, a major eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century port on the Raritan River opposite New Brunswick. The distance by road from Ringoes to Raritan Landing is about thirty-three miles, but the trip might have been shortened by using barges on the Raritan River.

Kemple Sherds Found by Sim, Brown, and Springsted

Robert Sim began his digs at the Ringoes pottery site in December 1950 and found stoneware sherds scattered thickly over the ground (fig. 53). Many were decorated—in cobalt blue applied with a narrow brush—with what he called “coiled spring” motifs (fig. 54). He also referred to them as “monkey tails” or “watch springs,” and recognized that they “are never as regular, neat and well spaced as they usually are on the Cheesequake 1776 [Morgan] sherds.”[49] James R. Mitchell, director of the New Jersey State Museum during the excavation, first recognized that the Kemple watch-spring motifs were often “knotched” (as he called it), whereas those from the Morgan pottery site—except for two known sherds—were plain.[50]

Kemple rim sherds in the Sim collections at MCHA and NJSM have incised cobalt-blue bands (figs. 55-57), but there are some in the collections on which the band is not present. In a notebook entry dated December 15, 1950, Sim wrote: “The jars and chamber pots were almost invariably decorated with one narrow blue line in the middle of three tooled depressed lines at the base of the collar. . . . The cobalt used is of a deep, bright tone.” In a summary written on November 22, 1951, however, he noted, “What I take to be the earliest type of crock made in that pottery has . . . a vertical collar [that] is very low and not separated from the shoulder by encircling lines or ridges. As a rule there is no encircling blue line at the base of the collar.”[51]

The four sherds illustrated in figure 58 are decorated with the pomegranate design seen on two attributed Kemple jars.[52] Figures 59 and 60 show the attributed Kemple jars illustrated in figures 6 and 7, each overlaid with one of the Kemple jar sherds from figure 58 with parts of the pomegranate design, demonstrating a remarkable match. Part of a similar motif is also on a sherd found at the Ringoes site by Brenda L. Springsted.[53] Other sherds are decorated with two small incised petal-like motifs, a curvilinear pattern filled in with cobalt blue, and a coggled sherd (fig. 61). These sherds show that Kemple also employed incising and used a coggle wheel for some of his designs.

Other digs were made at the Kemple site during this period by James S. Brown Jr. After visiting the Ringoes site, Brown wrote to Sim: “Looked over winter wheat field and picked up a small bag full of fragments including four more pieces of diamond incised beer mugs, unfortunately—couldn’t make any match up.”[54] These incised fragments demonstrate a highly competent technique after the Westerwald style of decorating (figs. 62, 63). A unique incised fragment (fig. 64) has a floral decoration similar to one seen on Morgan stoneware (see fig. 24).

A great percentage of the Kemple sherds must have been lost or mislaid, as correspondence between Sim and Brown indicates that there was a very large quantity of sherds found at the time of these excavations. Today, however, few remain in museum collections, especially those with watch-spring designs.

Kemple’s Relationship with Remmey and Crolius

It is interesting that New York potters Johannes Remmi (John Remmey) and Johann Willem Crolius (William Crolius) were both born in Neuwied in the Westerwald and came at about the same time to Manhattan. Crolius started his Manhattan pottery sometime before 1730. Remmey arrived about 1731 and also established a pottery.[55] Kemple arrived before 1739. The common background of these men makes it highly likely that they knew each other, and perhaps worked together. All were members of the Reformed Dutch Church of Manhattan. There appears to have been a close relationship between New York and New Jersey potters, allowing for an interchange of ideas influencing the various styles of pottery being produced in both locales.

A piece of evidence supporting the later bonds among these men is the fact, mentioned earlier, that William Crolius, grandson of Johann Willem Crolius, appears as a potter for James Morgan Jr. Branin suggests that since Mary Morgan, Captain James Morgan’s daughter, married potter Thomas Warne in 1786, Warne might have taken over the management of the James Morgan Jr. pottery after Crolius returned to New York City about 1790.[56] This marriage also might have motivated Mathias States to leave the Morgan pottery, since he was less likely to have the opportunities to advance to partnership or ownership of the pottery.

Relationships between Crolius and Remmey in New York and Morgan, Kemple, Staats (States) in New Jersey, and Mead in Connecticut

One of the most important recent advances in New York State stoneware research is Meta Janowitz’s archaeological study of the stoneware sherds found at the African American Burial Ground in Lower Manhattan, which she states were the products of the Manhattan Crolius and/or Remmey workshops dating from 1728 to circa 1765.[57] Some of these sherds, which are illustrated in her article “New York City Stonewares from the African Burial Ground” in this volume (p. 56, fig. 21), closely relate to the Morgan spiral design as well as to Kemple’s cogged spiral. Therefore, design is not always sufficient to support an attribution to one of these potteries. For example, the spiral and watch-spring designs found on stoneware vessels were long thought to be unique to Morgan and Kemple.

In fact, the jar illustrated in figure 2 was exhibited at the 1976 New Jersey State Museum bicentennial celebration with an attribution to Captain Morgan, and it was illustrated with the same attribution in William Ketchum’s American Stoneware, published in 1991.[58] The spiral design, which is similar to those found at the African Burial Ground (see p. 57, fig. 23, in this volume), now questions that attribution. Other features—the light gray color; the multiple narrow, closely placed circular incised lines below its rim; the lack of an interior slip; and the large spirals—suggest the Morgan pottery as its origin. It is possible that this design originated in the Manhattan potteries and was brought by workmen coming to Morgan’s pottery. However, if the jar had been made at the Crolius/Remmey workshop, it would be one of the earliest intact pieces of American salt-glazed stoneware (1730/40–1760).[59]

Nonetheless, the new information presented by Janowitz will require a major reevaluation of all vessels with a spiral design or variant that have been attributed to Morgan and Kemple. This is an exciting avenue for research, as there are other intact stoneware vessels with similar designs currently attributed to Captain Morgan’s pottery.[60] In contrast, to our knowledge, no image of an intact Crolius/Remmey vessel from this early period has been identified. The clay body of these sherds should be subject to spectrographic analysis to detect the variability among the various stoneware potters in New Jersey and New York. An initial study would include Crolius/Remmey, Morgan, and Kemple sherds found at their respective archaeological sites.

Scientific studies are needed to determine the clay sources of the potteries, the presence and concentration of other trace elements developed and/or added in the clay preparation, and variations in the salt glazes. An excellent detailed analysis and methodology of the elemental composition of Rhenish stoneware and glazes using neutron activation analysis, scanning electron microscopy, and systems energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry has been published.[61] Such an approach when combined with traditional methods of connoisseurship that emphasize analysis of stylistic features will help attribute the vessels to the different potteries.

Janowitz found that many sherds from different vessels at the African Burial Ground had interior slips: “The colors ranged from rose-brown through red-brown to light, medium, and dark brown . . . .”[62] In contrast, interior slips are characteristically absent from the Morgan and Kemple sherds observed by us.[63] But even this difference is not absolute, since Sim and Clement stated that there were some sherds “with a dark brown slip,” although we have not observed these in the sample examined for this study, except for one sherd (see fig. 38).[64]

What clay did the New York potteries use? There is no evidence that Charles Morgan Jr. was commercially exporting clay from his clay banks to ship to New York. The first possibility would have been after 1764, when Captain Morgan inherited the clay banks, but this postdates the 1730/40–1760 period in question, and at any rate there is no record of such sales. If New Jersey clay were used to make Crolius/Remmey stoneware, it could have been mixed with local clays. Additional evidence that New Jersey clay might not have been exported in this period lies in the search for suitable clay undertaken in 1742–1746 by Grace Parker, Thomas Symmes, and James Duché in their attempt to make stoneware for the first time in New England. They purchased clay from New York and Pennsylvania, which had successful potteries, and transported it to Charlestown, Massachusetts. There is no mention in the historical documents of New Jersey clay.[65] The first evidence for the sale from the clay banks dates to the ownership of General Morgan, Captain Morgan’s son, to stoneware potters in Massachusetts in the 1790s.[66]

Summary of Kemple and Morgan Stoneware Attributes

When connoisseurship criteria are used to evaluate and judge the overall appearance, form, glazing, color, and ceramic body, one can often make reasonable attributions of unmarked stoneware vessels likely made in New Jersey and New York City during the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century.

Because of the many similarities between Morgan and Kemple stoneware, one must rely on applied decorations to differentiate between the two. The sherds found at their pottery sites often permit reasonable attributions. This understanding is further enhanced by examining intact vessels thus attributed to both potteries to observe the decoration in its full context as well as additional motifs that might be present.

Both potteries decorated their vessels with a watch-spring design. The most characteristic differentiating feature was that the Kemple pottery added cogs to the simple spiral design as seen on sherds in figure 54 and on the intact attributed vessels (see figs. 3, 5, 6). Fortunately, attribution can be further broadened based on the sherds decorated with parts of pomegranates (see fig. 58) similar to those seen on the jars illustrated in figures 6 and 7. It should be noted that figure 6 also has the cobalt-blue cogged watch-spring design highlighted with reddish brown. The Kemple pomegranate motifs are brushed on and appear to be unique.

Another differentiating factor lies in the cobalt-blue bands found around the necks and sometimes the bases of many of the Kemple jars. Not all Kemple jars have the blue bands (see figs. 3, 5), but in our examination of the Morgan sherds we found the blue bands were most unusual around necks and bases (all banded sherds were from the Hunter Research excavation). We therefore conclude that, other factors being equal, the presence of a cobalt-blue line around the neck and/or base suggests a Kemple origin.

To add to the complexity of attribution, two sherds exhibiting the cogged watch-spring design were found at the Morgan pottery site by Sim (see fig. 47). However, the cogs were drawn differently from those made at the Kemple pottery, being shorter and stubbier. The watch springs on Morgan sherds and intact vessels are drawn more evenly spaced and regular than those on Kemple vessels, as noted by Sim (see fig. 53).

A Possible Source for the Watch-Spring Motif

The significance of the Crolius/Remmey sherds having a cogged spiral design that slightly resembles those seen on vessels decorated at the Kemple pottery must be addressed. Only two sherds illustrated by Janowitz as “notched spirals” were found among all the decorated fragments in the African Burial Ground.[67] Both have a partial spiral with two cogs that are broad, short, and not at all like those seen on Kemple sherds (see fig. 54), which are longer, thinner, and pointed. They do, however, appear similar to the cogs on the “Danniel Holmes” jar found by Sim at the Morgan site (see fig. 47).

We can speculate who might have introduced the cogged and uncogged spiral designs. For the cogged design, one of two potters who were in Manhattan at that time and who also probably worked at the Crolius/ Remmey potteries may have been responsible. One is Johan Pieter Kemple, who arrived by 1739 and later left with his family to establish his own pottery near Ringoes, New Jersey, in 1746. We may surmise that based on his own sherds, he elaborated on the original simple design.

The other potter is Adam Staats (States), who was in Manhattan from 1743 to 1746. His origin is not documented. Family tradition has Adam States emigrating from Holland and settling on Cheesequake Creek.[68] He is recorded as witnessing a baptism at the Reformed Dutch Church in Manhattan in 1743,[69] and was married there on August 28, 1744, to Elizabeth Gelderner.[70] He was still in Manhattan in 1746, when Peter Kemple witnessed the baptism of his first daughter, Anna Catherina States, at the same church, revealing a close relationship between the families.[71]

After 1746 Adam States was in South Amboy, New Jersey, for a short time and later traveled to Pennsylvania[72] and Rye, New York. He eventually went to Greenwich, Connecticut, about 1750, and became its first stoneware potter.[73] Adam’s son, Mathias, may have remained in New Jersey after his father left for Connecticut. As described earlier, Mathias served under Captain Morgan in the Revolution and could have been working for him at Morgan’s pottery no later than 1777. It is most likely that Mathias carried on his father’s motif of the watch spring.

Adam States appeared to have a special attachment to New Jersey. While living in Connecticut, he still owned land in Middlesex County, New Jersey, where he posted a bond on December 20, 1764, for a marriage license for his daughter Mary States, also of Middlesex County, to Nathaniel Palmer of Staten Island.[74] This was the same year Captain Morgan inherited property from his father, Charles Morgan Jr.

The exact date of Adam States’s death is not known. His wife, Elizabeth, a widow in 1769, was living in Great Egg Harbor, New Jersey, when she bound her son Adam to an apprenticeship with his uncle Peter States of Norwich, Connecticut, to learn the potter’s craft. After the elder Adam States died, his apprentice Abraham Mead (1742–1827) took over his Greenwich pottery in the 1760s.[75]

Although there is no known vessel with the cogged spiral design made by the elder Adam States, it is through his apprentice Abraham Mead that this design was fully exploited along with his own spiral motifs. Both of Mead’s designs, the spiral with or without cogs, are different in detail and configuration from those on the Crolius/Remmey sherds. In addition, further differences such as vessel form, clay firing colors, incised lines, and surface decorations make attributions between the two potteries apparent.[76] Finally, showing the complexity of the interaction among the potters are the spirals with cogs on Morgan’s “Danniel Holmes” jar and another Morgan sherd (see figs. 47, 48). This could have been made by Mathias States, Adam’s son, while potting for Morgan.

The strongest evidence that the spiral design was introduced into American stoneware motifs by Adam States is an attributed small spouted stoneware vessel (figs. 65, 66). Incised in script just above its base is “Elizabeth States her Pot” and below its left rim, the initials “E” and “S A S” with a historical ampersand (I with a crossbar) after the “E.” The letters after the second S appear to be written over and are illegible. We believe that this dedicated pot was most probably a gift from States to his wife, Elizabeth. The pot has slip-trailed spirals at both sides of its handle, which terminates in a scroll. The dotted circles in front, the multiple filaments, loops on its sides and below its handle remnants, all resemble the visual vocabulary on Morgan and Kemple sherds. These decorations suggest that States probably influenced these potters. States could have made Elizabeth’s pot while he was in Manhattan between 1743 and 1746.

The form and decoration of Adam States’s pot were new for American stoneware, resembling in part a Westerwald style reflecting the potter’s background as if he had just emigrated from the Westerwald or surrounding area. In fact, the terminal scroll on its handle is a Westerwald design seen on various sixteenth- and seventeenth-century stoneware vessels.[77] States applied slip trailing in a sophisticated fashion as a substitute for the intricate, carefully incised cobalt-blue curvilinear and other motifs seen on Westerwald stoneware. Based on the pot’s form, style, decoration, and the historical data of States’s whereabouts, we conclude that if he were working for Crolius/Remmey while he was in Manhattan, the pot was likely made about 1745. Elizabeth’s pot is the first objective evidence for the role of Adam States introducing the spiral motif as well as loops below the handle, possibly for the first time in America, found in both Morgan and Kemple designs and possibly those at the Crolius/Remmey potteries. To our knowledge, this is the only known vessel attributed to Adam States.

Summary

When the German potters immigrated to the colonies from the Westerwald district of Germany, they continued making pottery in their traditional ways. Classical salt-glazed Westerwald stoneware illustrated in books or exhibited in museums is highly decorated. The bodies of the jars, jugs, and mugs are embellished to varying degrees with complex surface decorations of elaborately incised animals, flowers, and foliated designs or with ornamental sprigs in relief or impressed rosettes. Circular bands were an added feature. These motifs were exuberantly colored in blue and manganese. The German-produced stoneware was executed with exquisite precision.[78]

The closest antecedents to the New York–New Jersey style of stoneware decoration are in the German Westerwald tradition. The potters’ cultural climate and the needs of the surrounding communities were not the same in America as in their homeland. The New York–New Jersey markets appear to have been less demanding than those in Germany, nor do the New Jersey potters seem to have achieved the technically refined, artistic proficiency of the Westerwald decorators. Perhaps lack of time, staff, or other responsibilities made the potters disinclined to decorate in a complex fashion. Motivated in a different direction, they focused their energy on bold forms and the use of brushed or slip-trailed cobalt-blue decorations.

We have found no evidence to show that the watch-spring motif was used in the Westerwald prior to its appearance in the New York–New Jersey area. This spiral design has had universal appeal from different potteries around the world from at least 5000 B.C. Fascination with this motif throughout the ages has not been limited to pottery but extends to bronzes, jewelry, textiles, and architecture. Variations of the spiral motif tie together Adam States, Abraham Mead, Captain James Morgan, the Kemple family, and the potteries of William Crolius and John Remmey.

Thanks to the prescient efforts of Robert J. Sim and James S. Brown Jr., who recognized the important contributions of these pioneering American potters, we have been left with a fragmentary legacy of these early New Jersey stoneware potters. The publication of these sherds in a color format will surely inspire other researchers to identify or reattribute intact pieces held in many private collections. At the very least, a better appreciation for the complex and intricate work produced by these early potters will be gained by all students of American ceramic history.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are most grateful for the cooperation and assistance of Lee Ellen Griffith, Ph.D., director, and Bernadette M. Rogoff, curator of collections, Monmouth County Historical Association, Freehold, New Jersey; James F. Turk, Ph.D., curator of cultural history, and Jana C. Balsamo, registrar, New Jersey State Museum, Trenton; Ulysses Grant Dietz, curator, Decorative Arts Collection, The Newark Museum; Kevin Stayton, chief curator, Brooklyn Museum; Bonnie Lilienfeld, deputy chair, Division of Home and Community Life, Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Washington, D.C.; and Richard Hume for copies of his historical documents.

New Jersey Department of Agriculture Press Release, November 29, 1955; “Sim, Naturalist, Is Dead at 75,” Trenton Evening Times, November 28, 1955. Sim was an avid collector of early farm and household utensils, tools, stoneware, and redware, which he photographed and described in Some Vanishing Phases of Rural Life in New Jersey (1941; reprint, Matawan, N.J.: Archives Press, 1965), and Pages from the Past of Rural New Jersey (Trenton, N.J.: New Jersey Agricultural Society, 1949). These publications include discussions of early New Jersey stoneware and redware and the results of his pioneering archaeological excavations of pottery sites and their sherd dumps. He researched the potteries of Captain James Morgan, Thomas Warne and Joshua Letts (Cheesequake), the Kemple family (Ringoes), Jacob Van Wickle, General James Morgan, the Bisset pottery (Old Bridge), and Nicholas Van Wickle (Herbertsville). Unfortunately, Early Arts of New Jersey, The Potter’s Art, c. 1680–c. 1900, exh. cat. (Trenton: New Jersey State Museum, 1956), had only two illustrations, one of a Parian vase, the other of a nineteenth-century pottery shop. New Jersey stoneware was extensively illustrated in New Jersey Pottery to 1840, exh. cat. (Trenton: New Jersey State Museum, 1972), which accompanied the show curated by James R. Mitchell, who later focused on the “The Potters of Cheesequake, New Jersey,” in Ian M. G. Quimby, ed., Ceramics in America, Winterthur Conference Report, 1972 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1973), pp. 319–38. The 1976 bicentennial exhibition at the New Jersey State Museum, “The Pulse of the People: New Jersey, 1763–1789,” included seven attributed James Morgan vessels, three reconstructed mugs, and 1775 and 1776 sherds from the Morgan pottery site.

This is discussed in an important article by Robert J. Sim and Arthur W. Clement, “The Cheesequake Potteries,” Antiques (March 1944): 122–25. Related discussions are in Arthur W. Clement, Notes on American Ceramics, 1607–1943 (Brooklyn, N.Y.: Brooklyn Museum, 1944), and Our Pioneer Potters (York, Pa.: Maple Press Company, 1947).

Sim and Clement, “The Cheesequake Potteries.” Arthur W. Clement (1878–1952), a lawyer by profession, was a member of the governing committee of the Brooklyn Museum and a trustee of the Brooklyn Museum of Arts and Sciences. He was a major collector of early American ceramics, researched, lectured, and published articles, catalogs, and pamphlets on early American decorative arts. His major legacy was the donation of his vast American ceramics collection to the Brooklyn Museum, and he assisted in its installation in a new gallery dedicated to ceramics in 1944. Today the museum has one of the finest collections of early American ceramics in the United States. He played a major role in educating and popularizing American ceramics through scholarly work and groundbreaking exhibitions at the Brooklyn and Newark museums. Credit for his intellectual contributions and generosity has been neglected. Biographical notes in the Arthur W. Clement Papers, Brooklyn Museum Archives (1l.f. [2.5db]); Arthur W. Clement and Edith Bishop, The Pottery and Porcelain of New Jersey, 1688–1900 (Newark Museum, 1947); Arthur W. Clement, Notes on American Ceramics 1607–1943 (New York: John W. Watkins Company, 1944). This handbook was written for the Brooklyn Museum’s exhibition of American ceramics commemorating the opening of a new gallery in January 1944; Arthur W. Clement, Our Pioneer Potters (New York: privately printed, 1947).

Robert Sim, personal notes on Ringoes, Hunterdon Co. Pottery; Monmouth County Historical Association (MCHA) Archives, Freehold, N.J.; Sim Notebook, December 15, 1950, multiple letters to James S. Brown Jr.; letter from James S. Brown to Robert Sim, dated “X-mastide,” 1950.

Brenda Lockhart Springsted, “Ringoes: An Eighteenth Century Pottery Site,” Northeast Historical Archeology 6, nos. 1–2 (Spring 1977): 66, fig. 7c, 57.

The symposium, entitled “Early Stoneware in New York and New Jersey: Origins of an American Industry,” was held at the New Jersey Historical Society in Newark on March 6, 2004. The audience and panel consisted of archaeologists, historians, collectors, and curators.

David Gaimster, German Stoneware, 1200–1900: Archaeology and Cultural History (London: British Museum Press, 1997), pp. 251–52.

Theodore Frelinghuysen Chambers, The Early Germans of New Jersey: Their History, Churches, and Genealogies (1895; Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Co. for Clearfield Co., 2000), p. 25. For many the journey was marked by terrible suffering (ibid., pp. 28–29):

[Since] very many, if not most of the emigrants were too poor to pay they were required to sell their time for three, four or five years to the captain in payment of their transportation. The poor emigrants thus became mere articles of merchandise, and were often treated accordingly. Being entirely at the mercy of heartless captains, who were not apt to learn compassion by this form of speculation in human beings, the poor emigrant rarely enjoyed on shipboard any but the most miserable accommodations and most insufficient food. Nearly all the horrors of the “middle passage” in the later times of Negro slavery were fully anticipated. [The passage was] sometimes prolonged to the period of ten months, and was seldom less than three or four. Closely packed together in over-crowded vessels with the narrowest accommodations, the frequent scarcity of food and water was generally the source of diseases, which became contagious, and death was sure then to reap an abundant harvest. . . . Children were torn from the arms of parents, never to be heard of again. Brothers and sisters were scattered often in different colonies and remained separated for years, and sometimes for life. In some cases these bond-servants soon earned their freedom, but they often succumbed to work beyond their strength or grew hopeless and despairing, and died of sheer homesickness.

Gaimster, German Stoneware, 1200–1900, pp. 251–52.

Franz Baaden, “Seit 350 Jahren: Westerwalder Steinzug in Amerika,” in Zeitschrift Schaulade (May 1982), p. 9 (translated from the German by L. M. Kolensky).

M. Lelyn Branin, The Early Makers of Handcrafted Earthenware and Stoneware in Central and Southern New Jersey (Cranbury, N.J.: Associated University Presses, 1988), pp. 33–35.

Laurel Ann Racine, “Re-Examination after Excavation: The Problems of Attributing Wares to Three New Jersey Stoneware Potteries” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 1997), p. 6.

Except for the period between September 1776 and March 1777, Captain Morgan was in the South Amboy area and could still manage his affairs, including the pottery, until it was destroyed by the British in 1779. Captain Morgan’s sons James Jr. and Nicholas served in his company, Nicholas as a lieutenant and James Jr. as a private, sergeant, and, finally, an ensign, the lowest officer rank. In later years James Jr. served in the State Militia as a colonel and eventually was promoted to the rank of major general. New Jersey Revolutionary War Service cards in the New Jersey State Archives, Trenton, and the National Archives, Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775–1883, Record Group 93 m 246, all from the David Library of the American Revolution, Washington Crossing, Pennsylvania.

Branin, Early Makers, p. 35.

James S. Brown Jr., “Notes on New Jersey Stoneware Potteries before 1850,” undated manuscript in the Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA.

Ken Stryker-Rodda, “New Jersey Ratables, 1778–1780, Middlesex County,” Genealogical Magazine of New Jersey 50, no. 3 (September 1975): 139.

In his manuscript on the New Jersey stoneware potteries before 1850, see note 15 above, James S. Brown Jr. speculates that the Morgan pottery was founded by members of the Staats family and notes that Matthias Staats is said to have worked later with General James Morgan, adding that “to date, no documentary proof of this has been found.”

James Noyes States, The Genealogy of the States Family (New Haven, Conn.: privately printed, 1913), p. 37.

A son “Mattattis” was born January 29, 1748, in Pennsylvania; Greenwich Births-Marriages-Deaths, 1640–1848, Barbour Collection, Connecticut State Library, 1926, p. 77. See also “Greenwich, CT Vital Records 1640–1848 from the Barbour Collection,” available online at www.rays-place.com/town/greenwich-ct/part6.htm (accessed March 27, 2008).

New Jersey State and United States Federal Records on Matthias States, David Library of the American Revolution, Washington Crossing, Pennsylvania.

Mathias States appears on the tax rolls of South Amboy Township, Middlesex County, New Jersey, for October 1780, August 1782, August 1783, August 1784, August 1785, and August/September 1786; see Ronald Vern Jackson, New Jersey Tax Lists, 1722–1822, 6 vols. (Bountiful, Utah: Accelerated Indexing Systems, 1981), 5: 3023. He appears in the 1790 U.S. Census for Fairfield, Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, as Mathias Steats, in the 1810 U.S. Census for the same town as Mathias States, and in the 1830 U.S. Census for Derry, Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, as Mathias Stutes, a misreading of the clearly written Mathias States.

John E. Stillwell, “Crolius Ware and Its Makers,” New-York Historical Society Quarterly Bulletin 10 (1925): 58; and Branin, Early Makers, p. 35.

Branin, Early Makers, p. 35.

Sim and Clement, “The Cheesequake Potteries,” p. 122.

Branin, Early Makers, p. 34.

Richard Hunter, William Liebeknecht, and Michael Tomkins, with Hamet Kronick and Patricia Madrigal, Phase II Archeological Survey, N.J. Route 34 (Cheesequake) Oldbridge Township, Middlesex County, New Jersey, Federal Highway Administration and New Jersey Department of Transportation, Bureau of Environmental Analysis, vol. 1, Narrative (November 1995; revised March 1996), pp. 4–18.

Branin, Early Makers, pp. 34–35.

Early Arts of New Jersey, p. 23; New Jersey Pottery to 1840, Trenton, Old Bridge, Middlesex County section.

“Ringoes, Hunterdon Co. Pottery,” p. 12, handwritten notes by Sim, December 15, 1950, Sim Collection, MCHA.

James S. Brown Jr., “Notes on New Jersey Stoneware Potteries before 1850,” p. 21, undated draft in the Robert J. Sim Collection, MCHA.

Ibid. The location of these sherds is not known.

Another, earlier view of the Holmes vessel is shown in Suzanne Corlette, The Pulse of the People: New Jersey, 1763–1789 (Trenton: New Jersey State Museum, 1976), p. 200, fig. 328.

The writing and design on the sherds has a faint cobalt-blue coloring and an overall brown color with a very dense orange-peel salt glaze. This is the result of poor firing.

Hunter et al., Phase II Archeological Survey. Hunter Research archaeological studies at the Morgan kiln site noted the surface treatment of 171 sherds found: 71% were applied by brush, 26% by slip cup, 2% incised, and 2% incised and brushed. The decorative motifs on 20 of these were: 5% floral, 5% watch spring and linear, 85% watch spring, minimum one spring, 5% watch spring, minimum two springs. Ibid., vol. 1, p. 6-9, Table 6.3, p. 6-10, Table 6.4.

Church records at Nordhofen, Kemple File; see www.ancestry.com: Jeff Burton Kemple.

Kemple was living in New York City in 1739; 1892 New-York Genealogical and Biographical Record, New-York Genealogical and Biographical Society, p. 196.

Chambers, Early Germans of New Jersey, pp. 427, 428.

Collections of the New-York Genealogical and Biographical Society, vol. 3, Baptisms from 1731 to 1800 in the Reformed Dutch Church, New York, p. 125: June 8, 1746.

The land had been purchased in 1731 by William Johnson from Daniel Coxe of Trenton, one of the proprietors of the Province of West Jersey, who incidentally operated one of the earliest potteries in New Jersey. Springsted, “Ringoes,” p. 57.

Ibid.

Peter O. Wacker, Land and People: A Cultural Geography of Preindustrial New Jersey Origins and Settlement Patterns (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1975), Table 3.10, p. 162.

See Johann Peter Rockefeller’s tombstone, which was erected by John Davison Rockefeller in the Old Dutch Cemetery in Ringoes. Springsted, “Ringoes,” p. 57.

Ibid.

Ibid.; and Branin, Early Makers, pp. 30, 31.

Springsted, “Ringoes,” p. 57.

Robert Sim to James S. Brown Jr., December 17, 1950, Robert J. Sim Collection, NJSM.

Robert Sim to James S. Brown Jr., November 20, 1951, Robert J. Sim Collection, NJSM.

Hunter et al., Phase II Archeological Survey, pp. 7-18, 7-20.

Robert Sim to James S. Brown Jr., November 20, 1951, Robert J. Sim Collection, NJSM.

James R. Mitchell to author, April 2, 1976, Hunterdon County Library, Flemington, N.J., containing a drawing of Ringoes and Cheesequake spirals, a photograph of which is in the Sim Collection, NJSM.

Robert J. Sim, handwritten notes regarding Ringoes pottery, November 22, 1951, p. 18, Sim Collection, NJSM.