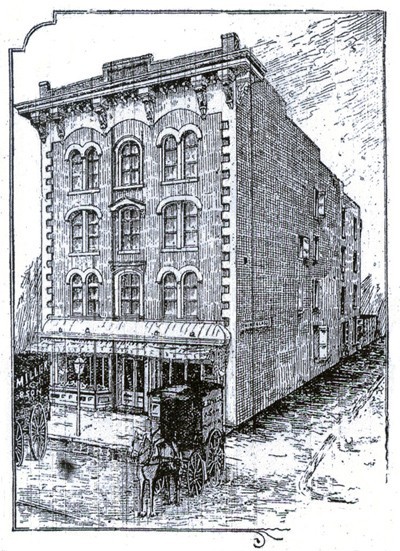

Advertisement, E. J. Miller & Son, 65 (later 317) King Street, Alexandria Gazette, September 16, 1893, suppl. ed. (Courtesy, Alexandria Library, Special Collections.). The advertisement states: “R. H. Miller commenced business in 1822 in one half of the present store. No change was made in the firm until 1857, when he rebuilt the store as at present.” Apparently the store was rebuilt earlier, however, as the November 7, 1856, Alexandria Gazette reports a “new and spacious warehouse recently erected” on the site.

Photograph, Miller Company, 31 (now 119) King Street, 1907. Reproduced in Alexander J. Wedderburn, Souvenir Virginia Tercentennial, 1607–1907, of Historic Alexandria, Virginia (Alexandria, Va.: A. J. Wedderburn, 1907). The caption reads, “This firm is old and reliable, having been established in 1822. Another Alexandria institution.”

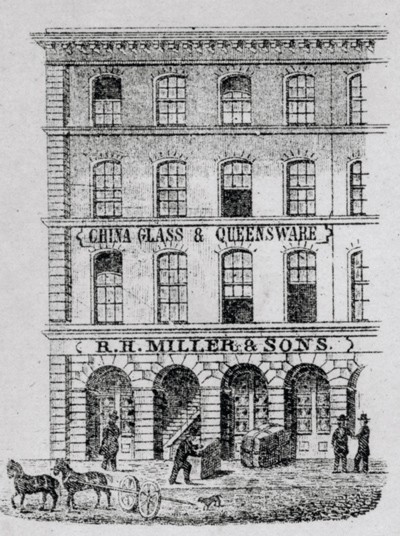

Engraving, R. H. Miller & Sons, 11 & 13 North Second Street, St. Louis, 1862. (Courtesy, Missouri History Museum, St. Louis.) Depicted is the third location of R. H. Miller & Sons, taken from a company receipt dated October 16, 1862. The address, no longer extant, is now within the confines of a waterfront park.

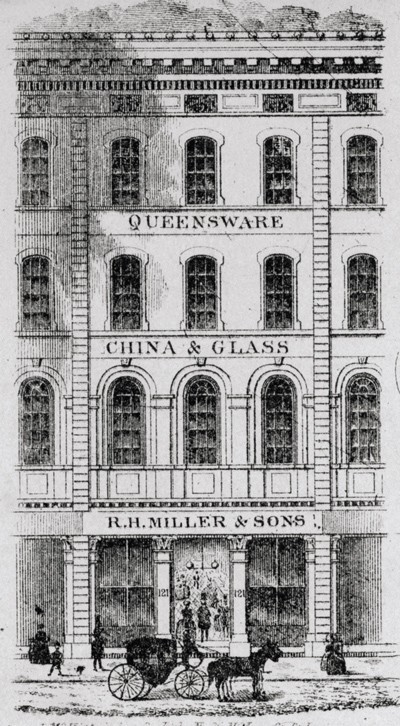

Engraving, R. H. Miller & Sons, 121 Fourth Street, 1862. (Courtesy, Missouri History Museum, St. Louis.) This fourth location of the company—in what was known as the Collier Marble Buildings—was taken from a company receipt dated May 16, 1862. By 1867 the address appears as 504 North Fourth Street.

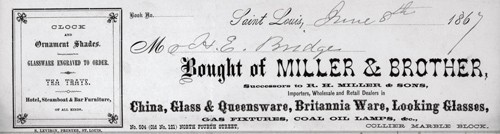

Receipt, Miller & Brother, “Successors to R. H. Miller & Sons,” dated June 8, 1867. (Courtesy, Missouri History Museum, St. Louis.)

Wash basin, Joseph Heath, England, 1848–1853. White ironstone. D. 13 1/2". Marks: printed on the underside, “MANUFACTURED FOR R-H MILLER & CO ST. LOUIS. M / IRONSTONE CHINA / J. HEATH.”; impressed under the printed mark, “PEARL WARE / J. HEATH.” (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum; photo by Gavin Ashworth.) This wash basin was found in a privy behind a house at 809 Duke Street, Alexandria.

Mark on the underside of the wash basin illustrated in fig. 6.

Plate, Thomas Dimmock (Junr) & Co. manufactory, Shelton, England, ca. 1835–1848. Ironstone, with transfer-printed Coral Border pattern. D. 10". Mark: printed on the underside, “stone ware / Coral Border / IMPORTED / BY / N. E. Janney & [Co.] / SAINT LOUIS” (Photo, Sangamo Archaeological Center.) Thomas Dimmock used similar manufacturer marks between 1828 and 1859, but this version limits the date. The plate was found in excavations in Mobile, Alabama, in an 1840s context.

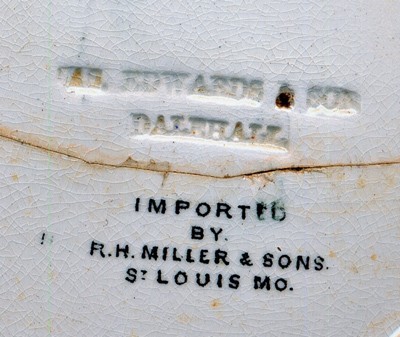

Saucer, James Edwards, England, ca. 1857–1865. White granite. D. 6 1/2". Marks: above transfer print, “KEOKUK PACKET CO.”; impressed on underside, “JAS. EDWARDS & SON / DALEHALL”; (printed), “IMPORTED / BY. / R. H. MILLER & SONS. / ST LOUIS MO.” (Photo, Sangamo Archaeological Center.) Archaeologists recovered this saucer from an 1850s context in St. Louis. Steamboats were vital to the city’s economy until they were overtaken by the railroads. This saucer may have been used on a steamboat traveling the 214 miles between St. Louis and Keokuk.

Marks on the underside of the saucer illustrated in fig. 9.

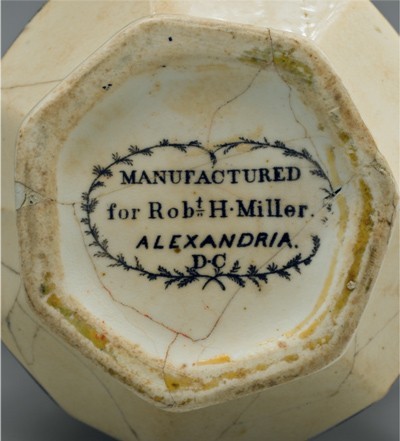

Pitcher, unknown maker, England, 1840. Bone china with overglaze transfer prints embellished with green enamel and purple luster. H. 5 1/8". Mark: “MANUFACTURED / for Robt.. H · Miller. / ALEXANDRIA. / D-C” (Courtesy, The Lyceum: Alexandria’s History Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This pitcher was imported by Robert H. Miller for the presidential campaign of William Henry Harrison. To the right of the handle is a log cabin with a plow, sheaves of wheat, a beehive, and a sign “TO LET IN 1841”; to the left is a portrait above a ribbon, labeled “HARRISON & REFORM,” flanked by cannons and flags marked “Tippecanoe” and “Thames,” references to Harrison’s famous military victories. The same prints, published by J. S. Horton of Baltimore and in the collection of the Library of Congress, American Political Prints 1766–1876, appear in green on other pitchers and plates manufactured for Miller and on a Whig campaign ribbon produced for the Young Men’s National Convention held in Baltimore on May 4, 1840.

Mark on the bottom of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 11. The printed mark has been found on other styles of Harrison campaign china.

Jar rims, B. C. Milburn (for E. J. Miller), Alexandria, Virginia, 1865–1876. Salt-glazed stoneware. These sherds, recovered from the waster pile at the Wilkes Street Pottery, are stamped “E. J. MILLER / ALEXA.” Robert H. Miller and his son E. J. ordered stoneware from the pottery from the 1820s until it closed, in 1876.

Jar, probably James Hamilton, Greensboro, Pennsylvania, ca. 1877–1900. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11 1/2". Mark: stenciled “E. J. MILLER & CO. / QUEENSWARE / ALEXANDRIA. VA. / 2” (Courtesy, The Lyceum: Alexandria’s History Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This two-gallon vessel with stenciled decoration and Albany slip interior is typical of the production of James Hamilton and others in the Greensboro–New Geneva region. Such items were sold at E. J. Miller’s store after Alexandria’s Wilkes Street Pottery closed in 1876.

Crucibles, possibly German, ca. 1823–1827. Earthenware with black sand and lead inclusions. H. of tallest 1 3/4". (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Miller advertised crucibles at least seven times between 1822 and 1847. These crucibles were found across the street from Miller’s shop on a property occupied from 1823 to 1848 by Alexandria silversmith John Adam. They were found along with debris from an 1827 fire.

Teacup and saucer, English, ca. 1820s. Pearlware, transfer-printed. D. of teacup 3 1/2"; D. of saucer 5 1/2". Mug, English, ca. 1845–1865. Ironstone with flow-blue transfer-printed design. D. 3 1/4". Teacup, English, ca. 1830s–1860s. Whiteware, blue sprigged-thistle design. D. 3 1/4". (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Miller offered for sale “blue printed (Liverpool) wares,” “flown” or “flowing blue” wares, and China tea sets described as having “pure white, blue raised figures.” The pearlware teacup and saucer and the ironstone mug were excavated from a residential property at 104 S. St. Asaph Street, Alexandria. The whiteware teacup is from a neighboring property, 522–524 King Street.

Robert H. Miller (1798–1874), a prominent figure in Alexandria, Virginia, was active in a number of civic and economic endeavors—at various times president of the Alexandria Water Company, president of the Citizen’s National Bank, a member of the Alexandria Common Council (the town’s governing body), a member of the Lyceum Company, and a trustee of the Female Orphan Asylum. An active abolitionist, he bought slaves in order to purchase their freedom and helped to establish Alexandria’s “Hayti” neighborhood by building homes and selling them to free blacks. He was instrumental in the establishment of the Alexandria Canal Company—which began operation in 1843, opening trade to the west—and served on its board of directors. Miller was also an officer of the Alexandria, Loudon, & Hampshire Railroad, chartered in 1853, and was one of the first shareholders in the Orange and Alexandria Railroad.[1]

In 1822 Miller opened a china shop on the main commercial street in Alexandria, at the edge of the Market Square, and in 1835, taking advantage of the burgeoning westward expansion and new transportation routes, he opened a second store, in St. Louis, Missouri. An interesting collection of surviving documents—memoirs of his children Warwick and Eliza, newspaper advertisements, receipts, early histories, and maps—sheds light on Miller’s stores. The most intriguing “documents,” however, are in the form of ceramics in the collection of the Alexandria Archaeology Museum that bear printed marks indicating that they were “MANUFACTURED / for Robt.. H · Miller. / ALEXANDRIA. / D-C.” or “MANUFACTURED FOR R-H MILLER & CO ST. LOUIS. M.” It is known, from detailed advertisements, what ceramics were available in Alexandria in specific years, and many of these pieces turn up in Alexandria’s vast archaeological collections. This article includes a review of about sixty Alexandria advertisements printed between 1822 and 1894, and eighteen Missouri advertisements from 1833 to 1856, although much archival research remains to be done.

Robert Hartshorne Miller was one of five sons of prominent Alexandria merchant Mordecai Miller, a Pennsylvania Quaker who went to Alexandria in the 1790s. According to Eliza Miller, her grandfather Mordecai “made quite a fortune in the West Indies, and South American trade: also shipping tobacco to Bremen.”[2] Robert and his brothers worked on their father’s merchant ships, purchasing and selling cargo.

Eliza wrote that her father learned the china business from another successful Alexandria china merchant, Hugh Smith, whose Potomac River wharf was next to Mordecai Miller’s, at the foot of Wilkes and Gibbon streets. Hugh Smith’s shop stood on the 200 block of King Street from 1803 to 1854. From 1825 to 1841, Smith also owned the Wilkes Street Pottery, where John Swann and B. C. Milburn made beautifully decorated stoneware that both Smith and Miller sold in their shops.

Miller was twenty-four when he opened his Alexandria store in 1822, and he purchased his first stock in England while returning from Bremen on his father’s ship.[3] A year later, he married Anna Janney, the daughter of a prominent Quaker family from Loudon County. Between 1824 and 1844 Robert and Anna had eleven children, all of whom survived to adulthood: Warwick, Charles, Elisha, Francis, Cornelia, John, Sarah, Mary Anna, Benjamin, Caroline and Eliza.

Miller’s first advertisement in the Alexandria Gazette listed “205 packages of china, glass and earthenware” from the brig Missionary, direct from Liverpool, “comprising a complete and extensive assortment. Having visited the manufactories and attended to the selection of the present parcel himself.”[4]

Personal selection of his stock remained a point of pride in many of his later advertisements. In 1825 the Alexandria store sold Lafayette commemorative wares “executed expressly for him, from a drawing sent out,” and in 1840 “earthenware of new style and patterns, manufactured for him within the past summer” and “ware with Harrison and Log Cabin engravings, from designs sent out to the Potteries by himself.”[5] Some of these Harrison wares bear Miller’s own printed mark. In 1853 Miller’s St. Louis store advertised “French China . . . imported direct from the manufactories of Paris.” The next year the Alexandria store offered “French Porcelain, imported through a resident French Agent in Paris,” and “our stock of earthenware . . . purchased by our resident agent in Liverpool” was advertised in St. Louis.[6] The 1858 Sketch Book of St. Louis describes some of Miller’s arrangements for importing ceramics:

In order that they might successfully compete with the Eastern jobbers, they a few years since made arrangements with European houses, by which means they import direct from the potteries in Staffordshire, England, every description of Queensware. . . . The importers of New York furnish them with supplies of French China ware, upon terms equally as favorable as they could obtain them were they to go to the fountain head.[7]

From the beginning Robert Miller had tried to reach a wide market, and his 1822 Alexandria advertisements stressed the importance of packing for transport: “Knowing the importance of having goods carefully and securely packed, R. H. M. has taken the precaution to procure an experienced and careful packer from the pottery; so that those who may favor him with their custom can rely upon receiving their ware in good order.” This packer was probably imported from England along with the pottery, as the local stoneware manufactory was struggling at this time and would not have had such specialized labor. An 1837 advertisement in the Alexandria Gazette states: “Country merchants within reach of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal will find it to their advantage to purchase of the subscriber, as they will be carefully packed and forwarded.”[8]

The store in St. Louis expanded the reach of Miller’s business far beyond that of the canal. In 1851 Miller advertised in the Liberty Weekly Tribune “a large stock of goods, ordered expressly for the Santa Fe trade. . . . Our goods are put up in the best manner, by careful and experienced packers, and may be transported any distance by wagon or otherwise, without risk of breakage.”[9] At the end of the century, an article in the Alexandria Gazette notes that the St. Louis branch “did a large business with Santa Fe and Indiana trades, and other states throughout the West and Northwest.”[10]

The Alexandria Store

Miller’s shop in Alexandria was located at 65 King Street (now 317 King Street), three blocks from the Potomac River wharves and one block west of his mentor Hugh Smith’s shop. Miller first rented the store from a relative, then purchased the building in 1835, the same year the St. Louis store opened.[11] In 1848 Miller “enlarged and fitted up his store in a commodious and comfortable manner.”[12] In 1856 a new partnership—R. H. Miller, Son & Co., which included Robert’s son and successor Elisha Janney Miller as well as Warwick M. Stabler, Samuel Howell, and F. Westwood Ashby—was “at the same place on King Street, in the new and spacious warehouse recently erected.”[13] Stabler and Howell left the business four years later.

Insurance maps from 1877 through 1907 show the footprint of this “new and spacious warehouse,” which was double the size of the old shop. The brick building had a thirty-five-foot frontage, stretching back ninety-five feet along Market Alley, which led to the market stalls in the interior of the block.[14] A drawing of the store appeared in the Alexandria Gazette in 1893 (fig. 1).[15]

Warwick P. Miller, Robert’s eldest son who in 1844 went to St. Louis to work in the family store, remembered that when he was a boy he often saw Robert E. Lee in his father’s Alexandria store. Like Lee, Warwick attended the Alexandria school of noted Quaker Benjamin Hallowell. Warwick recalls,

I did very little good at school, I had been at it since I could talk and was thoroughly disgusted when I was 14 [in 1838], father let me go to work in the store where I remained until I was 18. I then said I wanted to go to school again . . . and I studied faithfully and in those six months got what little education I have. I then went back to the store and by the time I was twenty had a good knowledge of the business and took great interest in it.[16]

Robert’s daughter Eliza’s account of playing with her sister Caroline (Carrie) provides us with a glimpse of the store’s layout:

I think it must have been in the fall of that same year [1851] that I had my first accident, falling from the second story of father’s store to the ground. Carrie and I used to think it great fun to go to the second floor and help the boys unpack the big crates of earthenware—the fine china and glass always came in hogsheads—but this time the crates contained yellow baking dishes. When it was empty and the straw put back into it, John [their brother and an employee] asked if we did not want to ride down in it to the lower floor—Carrie declined with thanks, but I was helped in and took hold of the chains that were hooked to each side and the crate was pushed out of the door to be lowered by the hoisting machine, but just as it swung out, one of the hooks came loose, the crate tilted and spilled me out into a cobble stone alley that ran at the side of the store. Fortunately, I did not go on through the cellar door below which was half open. . . . I was taken into father’s counting-room and a doctor called.[17]

Eliza wrote that her father, despite his personal opposition, supported Virginia when it voted to secede from the Union at the brink of the Civil War. Unlike many of the businesses in Alexandria, Miller managed to keep his shop open during the war, when the town was occupied by Union troops. His son Frank was, according to Eliza, “a strong Union man,” with influential friends in Washington who arranged for Robert to remain in Alexandria, where the Millers could protect their home from being taken by federal troops and used for a hospital or barrack. His son Elisha and his wife were among those who went to stay in the country, beyond Southern lines, and their house was indeed used for a barrack. The family removed much of the furniture, but Eliza reports that the soldiers removed everything that was left, even the lead water pipes and brass spigots. She recalled that in 1862, in the midst of the occupation,

father stayed at the store all day and I sent his dinner to him, as he had no regular help there. . . . [S]oldiers would go into father’s store and buy any old odd thing and send it home with all sorts of stories as to where it came from and to whom it had belonged, and father got rid of much old and undesirable stock in that way. I think he did not buy any new stock during the war, just kept the store open and sold what he could of what he had on hand.[18]

Robert retired in 1865 at the age of sixty-seven and turned over the business to his son and partner Elisha Janney (E. J.) Miller, who had first worked as a clerk at the store in 1845.[19] E. J. took as a partner T. B. Hudson, calling the company E. J. Miller & Co. In 1882 his son Ashby Miller joined the firm, which was then called E. J. Miller, Son & Co. Hudson left the business sometime before 1888 and the firm became known as E. J. Miller & Son. Although Robert died in 1874 and Elisha in 1895, the business carried on into the twentieth century. From 1899 to 1907 the firm, under the ownership of Ashby Miller, was once again called E. J. Miller & Co. In 1907 it became known as The Miller Co., and moved two blocks closer to the wharves, to 31 (now 119) King Street (fig. 2). A receipt from 1908 lists O. F. Carter as president and R. E. Miller as secretary of The Miller Company. The business closed sometime before 1917, when it was no longer listed in the directories.[20] The original building at 317 King Street was demolished in 1966 as part of an urban renewal project, but the building at 119 King Street still stands.

The St. Louis Store

St. Louis, founded in 1764 on the banks of the Mississippi, was a flourishing town with rapidly expanding steamboat traffic when Robert H. Miller and his wife’s brother, Nathaniel E. Janney, opened a shop there in 1835. By 1850 it was the largest city west of Pittsburgh. Railroads from the East terminated at the east bank of the Mississippi, and goods and people were transported by ferry to St. Louis on the west bank. The store was, according to the 1858 Sketch Book of St. Louis, established “by Messrs. N. E. Janney and R. H. Miller, and met with flattering encouragement until 1848 when Mr. Janney retired from the firm.”[21] From 1835 to 1848, the business was called N. E. Janney & Co. After Janney’s retirement, it became R. H. Miller & Co. R. H. Miller’s eldest son, Warwick, went to work in his uncle’s store in 1844 and was joined by his brother Charlie before 1851. In 1857 R. H. Miller’s two sons Charlie and John became partners in the St. Louis store, along with G. W. Berkley, under the name R. H. Miller & Sons. An 1867 receipt lists the business as Miller & Brother, a change that probably took place in 1865 when R. H. Miller retired. Warwick Miller recollected: “Uncle Nathaniel Janney was in father’s [Alexandria] store for several years where he learned the crockery business very thoroughly; in 1835 he went to St. Louis and opened a store in an old stone warehouse on the north side of Charles street between Main street and the levee.”[22]

The company occupied at least four different buildings during its history. In 1851 an advertisement noted that the business had moved to 34 Main Street, between Chestnut and Pine streets, “[t]he subscribers having removed from their old stand, to the new and very spacious warehouse one square below.”[23] In 1854, according to advertisements, the store had expanded to “Nos. 32 and 34 Main Street.”[24]

The company moved to the third location around 1857 when the business became R. H. Miller & Sons. According to the 1858 Sketch Book,

. . . recently their business has increased so rapidly as to compel them to seek other quarters. They accordingly selected an enviable location in that magnificent pile of buildings erected during the past season on Second street, between Market and Chestnut streets, where they have ample space to store and display their admirable stock.

This “magnificent pile” is illustrated on an R. H. Miller & Sons receipt dated October 16, 1862 (fig. 3), which lists the address as Nos. 11 & 13 North Second Street.[25] The building is described in the Sketch Book:

The arrangement of their wares could not be better, and presents to the visitor an imposing appearance. The basement and third and fourth stories contain their crates and unopened stock; the first and main business floor, the white and glassware and chandeliers; the second, the colored and heavier articles of crockery, candlesticks, etc. The first floor, which is devoted to the retail trade, contains every thing that could be desired, and arranged in a style well calculated to show the articles to good advantage. The room is about twelve feet high, thirty feet front, with a depth of over one hundred feet. Here are a corps of attentive clerks to attend to the wants of all who may wish to inspect or purchase their wares.[26]

Other receipts, dated May 15 and 16, 1862, and December 5, 1863, illustrate the fourth location, the Collier Marble Buildings at 121 Fourth Street (fig. 4). The company may have used the Second Street and Fourth Street buildings concurrently in 1862, but it is possible that a clerk used an outdated receipt for the October 1862 sale illustrated in figure 3, which still lists the Second Street address. On a receipt from June 1867 is printed “Bought of Miller & Brother, Successors to R. H. Miller & Sons,” with the address still at the Collier Marble Buildings (fig. 5). An 1875 panoramic view of St. Louis shows railroad bridges crossing the river, with tracks and a major roadway running one block north of the Collier Marble Buildings.[27] This topographical survey drawing emphasizes the importance of transportation to the Miller business, and the accessibility of the store to the major transportation routes of rail, road, and river.

The store was a large and successful concern, selling goods both wholesale and retail. As the Sketch Book enthused,

This is the most extensive house engaged in this trade in the Western States, and has not its superior even in New York City, either in point of variety of stock or liberality of prices. Here the retail dealer can secure every thing he desires, of any quality or pattern, and as cheap as can be purchased in seaboard cities. . . . Ever since this house offered itself as a candidate for a share of public patronage, it has received a large portion of the trade of our city . . . they have won an enviable reputation throughout the West, and of which they may well feel proud.[28]

In the Liberty Weekly Tribune (Liberty, Clay County, Missouri) in the 1850s Miller advertised English and French porcelain, white granite, blue-edged, “dipt,” painted, and printed wares, yellow ware, and Rockingham.[29] The five receipts in the collection of the Missouri Historical Society indicate a variety of goods sold in the 1860s and appear to be for wholesale purchases by Hamilton R. Gamble (1862), Hudson E. Bridge (1862 and 1867), and W. T. Essex (1863), all men of prominence. (Gamble, a Unionist, was provisional governor of Missouri during the Civil War.) Among the goods enumerated are a variety of French China and White Granite, a Parian syrup jar (molded porcelain with a bisque, marblelike finish), dipped pitchers (also known as mocha or annular wares), yellow ware bowls, a fancy mulberry (printed) toilet set and slop jar, and a black teapot. Hudson Bridge’s October 16, 1862, purchase was for an extensive list of china and glassware totaling $304.20 and included a pair of “Antique Vases” for $12.00.

A white ironstone wash basin with a printed mark showing that it was manufactured for the St. Louis store was excavated in Alexandria in 1981, found with other mid-nineteenth-century artifacts in a privy behind a home at 809 Duke Street, seven blocks from Miller’s Alexandria store (figs. 6, 7). The wash basin could have been brought to Alexandria by residents of this house, but probably some of the goods intended for the St. Louis store were imported through Alexandria and sold locally.

The Sangamo Archaeological Center in Elkhart, Illinois, has fragments of three dishes with importer’s marks from the St. Louis store. The mark “IMPORTED / BY / N. E. Janney & [Co.] / SAINT LOUIS” was found on an English ironstone plate with Thomas Dimmock’s Coral Border pattern (fig. 8). The plate was found in an 1840s context in Mobile, Alabama, and likely traveled by steamboat down the Mississippi River to Mobile, more than 500 miles from St. Louis.

A plain white ironstone plate found in St. Louis has the printed mark (not illustrated) “R. H. MILLER & CO / ST. LOUIS,” surrounded by scrollwork.[30]

A white granite saucer recovered from a late 1850s archaeological context in St. Louis bears several markings. In addition to a print of a steamboat and the words “KEOKUK PACKET CO.” in the cup well, the reverse bears both an impressed mark of James Edwards & Son and a printed mark of R. H. Miller & Sons of St. Louis. The marks date the saucer to between 1857 and 1865 (figs. 9, 10).[31] One of the Keokuk Packet steamboats, the New Lucy, was described in a contemporary diary as

a marvel of beauty, a dazzling white palace floating on the water. Her hull was 225 feet long, with 33-foot beam. She was built in St. Louis in 1852 and had the reputation of being about the fastest boat on the Missouri. When running light on long summer days, she could go from Jefferson City to Kansas City between daybreak and dark.[32]

As early as 1842 N. E. Janney & Co. advertised “Steamboat Ware” in the St. Louis newspaper, the Daily Missouri Republican, “gotten up expressly for the western boats, from patterns and drawings sent to the manufacturers by us. The views represent the exterior and interior of boats of the best model, and the ware is the granite of a good strong quality.”[33]

The 1858 Sketch Book states, “Messrs. Miller & Sons have devoted particular pains to selecting wares for hotels and steamboats, and we would recommend our river friends to give them a call.” The masthead of a receipt from June 8, 1867, lists “Hotel, Steamboat & Bar Furniture” among the offerings of Miller & Brother (see fig. 5).

Miller’s China and Earthenware: Advertisements and Archaeology

Miller’s first newspaper advertisement appears in 1822 and is somewhat vague and generic—“105 packages of china, glass and earthenware”—whereas later ones expressed more confidence and salesmanship: “comprising a general assortment of desirable goods of superior quality, and neat patterns, which he will sell as low, if not lower, than they can be purchased elsewhere” (1837). Occasionally a list of all of a particular ware’s available forms was included:

45 packages Canton China, consisting of dinner services complete; dinner, breakfast, tea and dessert plates, flat and deep; dishes of all sizes; covered dishes; salads; pudding dishes plain and scalloped; covered and uncovered vegetable dishes; beefstake [sic] dishes and covers; soup and sauce tureens; fish dishes and custard cups; breakfast bowls and saucers; sugars, creams and butter dishes and covers. [1838][34]

Although not exhaustive, more than sixty advertisements from the Alexandria Gazette are incorporated in the following preliminary study. Most date from 1822 to 1860, with additional ones from 1868, 1869, 1874, and 1893.[35] The Daily Missouri Republican (St. Louis) and the Liberty Weekly Tribune (Clay County, Missouri) carried advertisements for the St. Louis branch of the business. For this study, seven advertisements for N. E. Janney & Co. (1835–1845) and two for R. H. Miller & Co. (1851) were reviewed in the Daily Missouri Republican.[36] Nine advertisements for R. H. Miller & Co. (1851–1856) were reviewed in the Liberty Weekly Tribune.[37] From these advertisements, specific ware types are discussed in light of archaeological findings from Alexandria. These advertisements are proving useful in interpreting the archaeological record, providing dates for the appearance of certain wares in Alexandria, and giving an indication of their desirability. Further research in the Alexandria Gazette will fill in gaps in our knowledge, not only of the wares sold by Robert H. Miller but of ceramics, glass, and other goods offered by a variety of merchants and found at archaeological sites.

Commemorative Wares. Throughout his years of operation, Miller advertised a variety of commemorative or souvenir wares in the Alexandria newspaper, but they were not advertised in the St. Louis papers referenced in this work. In 1825 Miller offered China and “imitation China” “with a drawing of La Fayette & the surrender of Cornwallis. Executed expressly for him, from a drawing sent out.” Alexandria held a grand reception for Lafayette when he visited in October 1824 during his tour across America. In 1826 Miller sold “a further supply of Lafayette Ware” along with “China tea-sets gold edge and view of Mount Vernon.” In 1829 Alexandrians could purchase “plain and lustred pitchers, mugs, twiflers and muffins with an excellent portrait of General Jackson.” In 1840 campaign souvenirs were sold “with Harrison and Log Cabin engravings, from designs sent out to the Potteries by himself” (figs. 11, 12). Fragments of the described Lafayette, Jackson, and Harrison wares have been found on archaeological sites in Alexandria. These include a Lafayette and Cornwallis mug and a Lafayette coffee can from different sites, a lustered Jackson pitcher from another site, and Harrison wares including a plate, cup, two saucers, and a pitcher. The excavated Harrison and Log Cabin pitcher bears Miller’s import mark and matches an extant whiteware pitcher. A third Harrison pitcher, of bone china, is also marked with Miller’s name (see fig. 11).[38]

In the Alexandria Gazette in 1850 Miller advertised porcelain busts of Swedish-born opera singer Jenny Lind (1820–1887), who made her American debut in September 1850 and was an immediate sensation; a review of her concert in Richmond, Virginia, appeared on the page following Miller’s advertisement.[39] The English firm Copeland and Garrett produced a bust of Lind in Parian, also known as statuary porcelain, and they may have produced the bust sold in Miller’s store.

Miller also sold humorous printed wares, as indicated in an 1833 Alexandria Gazette article: “We were amused, day before yesterday, at the ingenuity and wit displayed at Mr. Miller’s and Mr. [Hugh] Smith’s China Stores, representing the ‘progress of steam.’ One of them, now at Green’s Barber Shop, shows off a row of jolly fellows, all ready lathered, with the Steam Shaving Machine just about to commence operations.”[40]

In 1899 E. J. Miller & Co. advertised in Alexandria’s sesquicentennial program: “We are the oldest distributors of Souvenirs on China of Photographs of Old Christ Church, Where Washington Worshipped; Marshall House, Where first blood was spilled in our Civil War; Carlyle House, Braddock’s Headquarters in Revolutionary War.”[41] These souvenirs were manufactured by Benjamin F. Hunt & Sons, and are marked on the base: “B. F. H. S. / CHINA / MADE IN AUSTRIA / for E. J. Miller & Co. / Alexandria Va.” Pitchers and trinket boxes with this mark, with black printed designs and molded and gilt borders, survive in museums and private collections.[42]

Alexandria Stoneware. Miller regularly sold stoneware from the local Wilkes Street Pottery in his Alexandria store.[43] When Miller first advertised “Stoneware of Alexandria manufacture, of excellent quality” in the Alexandria Gazette on July 14, 1825, John Swann was the potter, although rival china merchant Hugh Smith had recently purchased the manufactory. Miller advertised Alexandria stoneware more frequently in the 1840s, after B. C. Milburn purchased the pottery from Smith. One advertisement read: “I am constantly receiving from the Pottery supplies of fresh made stoneware of superior quality” (Alexandria Gazette, October 24, 1843). At that time (1841–1847) the Milburn pottery was producing gray salt-glazed stoneware stamped “B. C. MILBURN / ALEXANDRIA D.C.” with beautiful brushed-cobalt floral decoration. In these years, Milburn also produced stoneware with the stamps of merchants H. C. Smith and Dubois & Reddick, but he is not known to have marked stoneware with R. H. Miller’s name.

An E. J. Miller advertisement published in the Alexandria Gazette on February 19, 1869, after the Civil War, read: “The Alexandria Pottery being again in full operation, I am prepared to furnish my customers and the public generally with STONEWARE of all kinds and of first-rate quality.”[44] By this time Milburn’s son, Stephen C. Milburn, was running the pottery and producing mostly undecorated utilitarian wares. After he took over his father’s store in 1865, E. J. Miller ordered stoneware from the Milburn pottery stamped with his own name. Two sherds stamped “E. J. MILLER / ALEXA” were recovered in excavations at the kiln site (fig. 13), and a number of intact jars, milk pans, jugs, and bowls with this mark survive in museums and collections. After the Alexandria Pottery closed in 1876, E. J. Miller ordered stoneware, stenciled with advertisements for his business, from potters in the Greensboro–New Geneva area of southwestern Pennsylvania. In the years after the Civil War, James Hamilton & Co. and other potteries in this region sold stoneware to ceramic dealers in the East and Midwest, and many examples survive. Stencils of various designs often included the name and address of Miller’s shop (fig. 14).

In June 1845 N. E. Janney advertised “4000 gallons of superior quality stoneware” in the Daily Missouri Republican.[45] The source of stoneware sold in St. Louis is unknown, but it is unlikely to have come from as far away as Alexandria. In this period, the hand-thrown stoneware usually had a local or regional market, while factory-produced wares such as white ironstone, yellow ware, and porcelain had wide distribution.

Crucibles. A specialized industrial product used for heating metals, crucibles were advertised in the Alexandria Gazette numerous times in the 1820s and 1840s. The advertisements usually specified “black lead and sand crucibles.” One 1841 advertisement specified sizes, for a stock of “2000 numbers of German lead crucibles from No. 3 to No. 36.” Four small crucibles were found in a privy behind 320 King Street, where silversmith John Adam worked from 1823 until 1848, and were discarded around the time of an 1827 fire. The gritty sand temper is visible in the clay, and the heaviness of the vessels attests to some lead content (fig. 15).[46]

Porcelain. European porcelain was widely advertised in both cities, while Chinese porcelain was mentioned in just three Alexandria advertisements. Miller’s 1832 and 1838 advertisements refer to “India china”[47] rather than Chinese porcelain, a common term referring to the East India Company that exported vast quantities of the ware. In 1852 the Alexandria Gazette advertised “a few pairs of Canton China Vases, of large sizes, an unique article, rarely to be met with,”[48] referring to the heavy blue-and-white porcelain decorated in the port city of Canton.

French porcelain, first advertised in the Alexandria Gazette in 1829, was clearly an expensive and coveted product. Advertisements describe “one splendid set French dinner China” (1829), “superior French China Tea Sets, 86 pieces, complete, with coffee pots” (1832), “extra fine sets” (1847), and “handsome French China” (1849). French china often took top billing in large print above Miller’s name, and on occasion even warranted its own advertisement. Miller advertised a wider variety of French porcelain forms than any other ceramic forms. In addition to dinner and tea sets he sold dessert sets, chocolate cups and saucers, fancy coffees, and mugs; serving pieces, including flat and deep dishes, carved dishes, oyster dishes, salads, compotes, fruit baskets, and pitchers; and ornamental pieces, such as gilt mantel ornaments with flowers and landscapes, vases, candlesticks, inkstands, toilet bottles, card baskets, fancy colognes, and spittoons. He even advertised toy tea sets as Christmas gifts in 1846.[49]

E. J. Miller’s Alexandria advertisements from 1893 promote

the new “open stock” patterns of Charles Fields Haviland’s French China, which we now have on exhibition. . . . An “open-stock” pattern is always desirable from the fact that YOU CAN BUY A PART OF A SET AT THE SAME RATE THE ENTIRE SET COSTS. Broken pieces can be replaced when desired and additions to your set can be made whenever you wish. . . . Messrs. Haviland & Abbot, the manufactures of this China, mailed to a number of our customers here in December a copy of their excellent little pamphlet descriptive of their various productions.[50]

Archaeologists in Alexandria frequently find Haviland china bearing marks dating from the 1870s to the 1890s, but these have not been found with importer’s marks.

For his St. Louis shop Miller advertised “white, gold band and decorated French” china (1851), and “plain white, gold band and decorated dinner, tea and toilet sets; vases, mugs, &c., in every variety, of our own importation” (1854).[51] Store receipts from the 1860s show the sale of: gilt and fancy French china toilet sets; gilt and decorated candlesticks; decorated spittoons and vases; gilt-banded soup tureens; white breakfast, dinner, and soup plates; dishes, bakers, and covered dishes; soup and sauce tureens; sauceboats and stands; gravy tureens; pickles; salads on foot; baskets on foot; mustard tureens; teas; sugars; covered bowls; pitchers; covered butters and drainers; oil comports; leaf custards; coffee cans and saucers; candlesticks; pitchers; and spittoons.

English china is specified in St. Louis advertisements from 1851 to 1854, including “pure white, enameled, luster, blue figured and gold band.” Some advertisements in the Alexandria Gazette do not specify a country of origin, but seem to refer to English or European porcelain. China “richly gilt, plain and embossed” was advertised in 1824; “One splendid gilt punch [i.e., pierced] China dinner and dessert service, 312 pieces, very cheap” in 1829; and, in 1841, “Breakfast tea cups and saucers, Greek and American shapes, as well as gold banded.” An 1838 advertisement for “China Tea Setts, ‘pure white’ blue raised figures” describes blue sprigged tea wares often decorated with thistles or floral urns (fig. 16, far right), which are commonly found at archaeological sites in Alexandria in both English bone china and whiteware.[52]

Austrian and German porcelain became very popular in the 1890s and frequently are found at Alexandria sites of this period. In 1893 E. J. Miller offered “Carlsbad 56 piece tea sets, 4 styles” and with gold bands. This refers to porcelain from the Carlsbad China Factory, a decorating workshop in Austria, whose products were imported by Ahrenfedt and Son, New York, from 1886 to 1910.[53] An advertisement later in 1893, for “Holiday Goods,” mentions both Haviland and “Fancy Dresden” porcelain.[54]

Ironstone and White Granite. Miller’s 1820s Alexandria advertisements for “Ironstone China table services” and “One splendid set English stone china” refer to Mason’s Patent Ironstone China (first made by G. M. and C. J. Mason in 1813) or early imitators. This ware is similar in appearance to whiteware with painted or printed decoration, and few pieces have been identified archaeologically in Alexandria. Heavier white ironstone or white granite, plain or with molded decoration, are common on Alexandria sites from the middle and late nineteenth century and were first manufactured in England about 1842. Miller first advertised white granite in Alexandria in 1845 as “White granite Dining Sets, white Granite Toilet Sets, Ewers and Basins, &c.” An advertisement from 1853 refers to “English Goods, from correspondents of 30 years standing, comprising Stone, China, white. . . .” An advertisement from 1860 lists “21 crates of white granite queensware from Liverpool,” using the term originally coined in the eighteenth century to describe the more delicate creamware. E. J. Miller advertised white granite from Hanley, England, in 1893.[55]

In the 1850s Miller’s St. Louis company advertised “white granite” and “gold band granite.”[56] In 1862 and 1863 Hudson E. Bridge and W. T. Essex purchased a variety of white granite from the St. Louis store. The vessel forms included plates, dishes, sugars, teas, pitchers, cake stands, bowls, toilet sets, slop jars, mugs, ewers and basins, and covered chamber pots.

Printed, Edged, Enameled, and C. C. Wares. In Alexandria in 1824 Miller advertised “Blue printed (Liverpool)” wares, including plates, cups and saucers, pitchers, mugs, and so forth; in 1829, “One dinner set, English stone China, oriental japan, 212 pieces, splendidly gilt.” Technological changes that allowed manufacturers to provide a variety of printed colors are reflected in later advertisements. By 1832 the advertised color range expanded to blue, black, purple, and pink; green was added in 1833. In 1838 dinner services were offered in “blue, brown, green printed, pearl white, and dove colored,” and an 1841 Miller advertisement referred to Liverpool ware in “pure white and fancy colors.” Printed wares were offered not only in dinner and tea wares but also, in the 1830s, as ewers, basins, and toilet sets. “A full assortment of flowing blue or Kaolin Dinner Sets, Toilet Sets, and extra pieces of Dining & Tea Ware” were first offered late in 1845, the year this ware was first imported to America. “Flowing blue” and mulberry-colored dining sets were offered in 1848 (fig. 16).[57] A set of flow blue china marked “KIN-SHAN / E. C. & CO..” (E. Challinor and Co.), complete with dishes, platter, tureen, pitcher and teapot, was found in a privy across the street from Miller’s store.

Edged plates and dishes (shell-edged wares with a blue molded rim) and enameled (painted) bowls were first listed in an 1826 Alexandria Gazette advertisement. Edged and enameled wares were listed together through the 1850s. An 1854 advertisement refers to “Common Blue Edged Ware.”[58] These are found at all nineteenth-century sites in Alexandria. In 1826 the enameled bowls most likely had simple hand-painted blue floral designs, but may have had the earth-tone colors found on pearlware such as green, brown, orange, and golden yellow. Beginning in the 1830s whiteware bowls usually had brightly colored decoration in red, black, blue, and bright shades of green. Alexandria Gazette advertisements from 1829, 1847, and 1848 refer to “C. C. ware,” which stands for common color or cream-colored ware—an inexpensive plain ware.[59]

Advertisements in the Liberty Weekly Tribune in 1851 describe “C. C. blue edged, dipt, painted, printed, white granite, fleur, blue and mulberry earthenware,” adding “flown” in 1852 and, in 1853, “agate, painted-flown-blue and Mulberry, printed-flown-blue and Mulberry, Canton blue, (and) fancy luster.” In 1854 the St. Louis store also sold earthenware that was sponged, “fancy luster and japanned,” and “Mat blue printed.”[60]

Black Teapots. An 1838 advertisement from Alexandria listed “Fine Black and Brown Tea Pots, all sizes,” and a receipt from the St. Louis store dated October 16, 1862, lists the sale of a black teapot for 60 cents. These probably refer to glazed earthenware—English imports, or possibly from Philadelphia. An 1850 Alexandria advertisement specifies “Wedgwood teapots—fine black teapots, assorted sizes,” referring to the refined black stoneware known as basalt.[61]

Yellow Ware. Yellow ware was imported from England and also manufactured in America, in the Ohio Valley, New Jersey, and, by the late 1840s, as close to Alexandria as Baltimore, Maryland. The earliest advertisements for these hard-bodied utilitarian wares (in Alexandria, 1838) mention

Ironstone or Fire Proof Earthenware. Round baking dishes from 7 to 11 inches, milk bowls with and without lips, ewers and basins, and chambers, covered and uncovered pickling and preserving jars . . . collenders, pitchers and patty pans, and Fire proof baking dishes, pitchers, teapots &c.

Yellow baking dishes were being unpacked in the store when Eliza had her accident in 1851. In the Alexandria Archaeology collection there are numerous examples of yellow ware in many of these forms, and some late-nineteenth-century examples of baking dishes, jars, and patty pans in a heavy white ironstone. The Liberty Weekly Tribune advertised yellow and Rockingham ware at the St. Louis store in 1855 and 1856.[62]

Conclusion

This brief study sheds some light on the business practices of one prominent ceramics importer and on the westward expansion of his business, and helps to elucidate findings from the archaeological record. In Alexandria, more extensive research could examine the statistical prevalence on archaeological sites of wares listed in the advertisements of R. H. Miller and his competitor H. C. Smith, and could draw on George L. Miller’s work on consumption patterns and pricing of imported ceramics.[63]

It is hoped that the Alexandria approach of examining archaeological collections in light of advertised wares may help with the analysis of assemblages from other cities. Research could look at general patterns of consumption of advertised wares in selected cities, or specifically at the incidence of importers’ marks on archaeological sites across the country.

An encyclopedia of ceramics marks lists seventy importers marks from china merchants in thirty-six American cities.[64] An extensive search of archaeological publications and of site reports in the “gray literature” would no doubt bring to light many examples of ceramics with importers’ marks. In just one example, ceramic marks of New Orleans importer Hill and Henderson and successor companies (1822–1877) have been found on archaeological sites in seven states, from Louisiana to California.[65] In the future, comparative studies between cities will become more practical, as compendia of importers’ marks, advertisements, and invoices are compiled for more cities, and as archaeologists and government agencies make searchable copies of unpublished archaeological reports and artifact inventories available on the internet.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank archivist Dennis Northcutt from the Missouri Historical Society for searching for additional Miller receipts and references, and Robert Mazrim of the Sangamo Archaeological Center in Salisbury, Illinois, for providing photographs of additional Robert H. Miller imports. I would also like to thank George Coombs from the Alexandria Library, Special Collections, for his assistance with Alexandria reference materials, and the staff and volunteers of Alexandria Archaeology who over the years have contributed to research and excavations relating to Robert H. Miller.

The Alexandria, Loudon & Hampshire line was intended to reach the coal fields in West Virginia. Construction began in 1855, but progress was slow and the tracks reached Leesburg only by 1860. “Alexandria, Loudon & Hampshire Rail Road Account Book, Guilford, VA, 1860–1868” (M-002), Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, Va. For more on the life and civic activities of Robert H. Miller, see Perry Wheelock, Robert Hartshorne Miller, 1798–1874: A Quaker Presence in Virginia (Alexandria, Va.: Alexandria Archaeology Publications 61, 1995); Francine W. Bromberg, Steven J. Shephard, Barbara H. Magid, Pamela J. Cressey, Timothy Dennee, and Bernard K. Means, “To Find Rest from All Trouble”: The Archaeology of the Quaker Burial Ground Alexandria, Virginia (Alexandria, Va.: Alexandria Archaeology Publications 120, 2000), pp. 20–22, 72–73, 79–83; and Philip Terrie, “A Social History of the 500 Block, King Street in Alexandria, VA” (1979), manuscript in the collection of the Alexandria Archaeology Museum.

Eliza H. Miller, “Personal Recollections of Eliza H. Miller,” 1926, p. 1, manuscript in the collection of the Alexandria Library, Special Collections.

Warwick Price Miller, Reminiscences of Warwick P. Miller of Alexandria, Virginia 1896 ([Alexandria, Va.]: Lloyd House, Alexandria Library, 1981), p. 3.

Alexandria Gazette, October 8, 1822.

Alexandria Gazette, July 14, 1840, and September 16, 1840.

Liberty Weekly Tribune, October 21, 1853; Alexandria Gazette, February 15, 1854; Liberty Weekly Tribune, April 14, 1854.

Jacob N. Taylor and M. O. Crooks, Sketch Book of St. Louis: Containing a Series of Sketches of the Early Settlement, Public Buildings, Hotels, Railroads, Steamboats, Foundry and Machine Shops, Mercantile Houses, Grocers, Manufacturing Houses, &c. (St. Louis, Mo.: George Knapp and Co., 1858), pp. 371–73.

Alexandria Gazette, October 8, 1822, and November 27, 1837.

Liberty Weekly Tribune, February 21, 1851.

“A Picture of Alexandria, and a Review of Her Business Interests,” Alexandria Gazette, suppl. ed. 94, September 16, 1893, p. 4.

Throughout his life Miller maintained business relations with various relatives in the close-knit Alexandria Quaker community. Sons, brothers, brothers-in-law, and cousins worked in the business.

Alexandria Gazette, September 23, 1848.

Alexandria Gazette, November 7, 1856.

See, for example, Griffith Morgan Hopkins, City Atlas of Alexandria, Va. 1877 (1877; reprint, Alexandria, Va.: Friends of Local History, Alexandria Library, Special Collections, 2000), p. 35; Alexandria, Virginia (New York: Sanborn Map and Publishing Co., 1885), p. 4; Alexandria, Virginia (New York: Sanborn Perris Map Co., 1891), p. 5; Insurance Maps of Alexandria, Virginia (New York: Sanborn Map Co., 1896), p. 10; and Insurance Maps of Alexandria, Virginia (New York: Sanborn Map Co., 1907), p. 8.

Alexandria Gazette, September 16, 1893.

Warwick Miller, Reminiscences, pp. 7–8.

Eliza Miller, “Personal Recollections,” pp. 4–5.

Ibid., pp. 18–21.

A receipt dated February 13, 1867, from “E. J. Miller, successor to R. H. Miller, Son & Co.” at 65 King Street, lists the sale of white granite plates, dishes, covered dishes, teapots, creamers and bowls; Alexandria Library, Special Collections.

A Concise History of the City of Alexandria, VA, from 1868 to 1883, with a Directory of Reliable Business Houses in the City (Alexandria, Va.: Alexandria Gazette Book and Job Offices, 1883), p. 65; Chataigne’s Directory of Alexandria and Fredericksburg, Containing a General and Business Directory of the Citizens of the Two Cities Together with a Complete Business Directory of the Counties of Alexandria, Fairfax, Fauquier, Loudoun, Prince William and Spotsylvania (Washington, D.C.: J. H. Chataigne, 1889), p. 134; Richmond’s Directory of Alexandria, VA 1900 (Washington, D.C.: Richmond and Co., 1900), p. 161; Alexander J. Wedderburn, Souvenir Virginia Tercentennial, 1707–1907, of Historic Alexandria, Virginia (Alexandria, Va.: A. J. Wedderburn, 1907), p. 93. Wedderburn illustrates the shop at its new location, showing a bank in place of the original store.

“R. H. Miller & Sons, Importers and Wholesale and Retail Dealers in China, Glass, Queensware, Brittania Ware, Tea Trays, Lamps, Chandeliers, &c., Nos. 11 & 13 Second Street,” Taylor and Crooks, Sketch Book of St. Louis, pp. 371–73.

Warwick Miller, Reminiscences, p. 19.

Liberty Weekly Tribune, February 21, 1851.

Liberty Weekly Tribune, April 14, 1854, March 2, 1855, August 10, 1855, and May 16, 1856.

The Sketch Book of St. Louis lists the address as “Nos. 11 & 13 Second Street,” but the receipts record it as “Nos. 11 & 13 North 2nd Street.” The Missouri Historical Society archives include R. H. Miller receipts dated May 15, 1862 (Hamilton R. Gamble Papers); May 16, 1862, and December 5, 1863 (Business Letterheads Collection); and October 16, 1862, and June 8, 1867 (Hudson E. Bridge Papers).

Taylor and Crooks, Sketch Book of St. Louis, pp. 371–73.

Richard J. Compton and Camille N. Dry, Pictorial St. Louis: The Great Metropolis of the Mississippi Valley, a Topographical Survey Drawn in Perspective A.D. 1875 (St. Louis, Mo.: Compton and Company, 1876).

Taylor and Crooks, Sketch Book of St. Louis, p. 372.

Liberty is approximately 235 miles west of St. Louis, on the outskirts of Kansas City.

The mark on the white ironstone plate is illustrated in Robert Mazrim and John Walthall, “Queensware by the Crate”: Ceramic Products as Advertised in the Saint Louis Marketplace 1810–1850, Archival Studies Bulletin 2 (Elkhart, Ill.: Sangamo Archaeological Center, 2002), p. 19.

This impressed potter’s mark was used circa 1851–1882, but the presence of the company name “R. H. Miller & Sons” in the printed merchants’ mark dates the saucer to between 1857 and 1865.

One Way Ticket to Kansas: The Autobiography of Frank M. Stahl, as Told and Illustrated by Margaret Whittemore, transcribed by John D. Meredith (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1959), p. 32. The New Lucy was owned by the Keokuk Packet Company in 1852, but Stahl traveled on it in 1856 when it was owned by another line.

Daily Missouri Republican, June 6, 1842. The advertisement is illustrated in Mazrim and Walthall, “Queensware by the Crate,” p. 15.

Alexandria Gazette, October 8, 1822, November 27, 1837, and May 9, 1838.

Advertisements were frequently repeated over a period of months, although Miller often placed at least two new ads each year; the earliest known date is given for each. The Alexandria Gazette, which printed daily from 1784 to 1994 with a hiatus during the Civil War, was the longest-running daily paper in the country. It is available on microfilm at the Alexandria Library, Special Collections.

These advertisements are printed or described in Mazrim and Walthall, “Queensware by the Crate.”

The Liberty Weekly Tribune was published in Liberty, Clay County, Missouri, from 1846 to 1883. Selected issues are included in the Missouri Newspaper Project, State Historical Society of Missouri.

Barbara H. Magid, “Commemorative Wares in George Washington’s Hometown,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2006), pp. 2–39, figs. 33–36.

Alexandria Gazette, December 25, 1850.

Alexandria Gazette, May 25, 1833.

The Official Programme Sesqui-centennial Business Directory (Alexandria, Va.: A. J. Symonds, October 12, 1899).

See Magid, “Commemorative Wares,” pp. 32–33, figs. 39–41.

The pottery was sometimes referred to as the Alexandria Pottery or the Milburn Pottery, but most references do not provide a name. Today it is commonly known as the Wilkes Street Pottery.

Alexandria Gazette, February 19, 1869.

Mazrim and Walthall, “Queensware by the Crate,” p. 17.

Alexandria Gazette, May 5, 1829, and May 24, 1841. Crucibles were also advertised in the issues of October 8, 1822, May 18, 1824, January 3, 1829, July 15, 1843, and October 22, 1847.

Alexandria Gazette, December 24, 1832, and May 9, 1838.

Alexandria Gazette, September 4, 1852.

Alexandria Gazette, May 5, 1829, December 24, 1832, March 9, 1847, December 3, 1849, and January 16, 1847 (advertisement dated December 2, 1846). Long lists of French porcelain forms appeared in those of May 24, 1841, and February 15, 1854.

Alexandria Gazette, March 21, 1893.

Liberty Weekly Tribune, February 21, 1851, and April 14, 1854.

Liberty Weekly Tribune, February 21, 1851; Alexandria Gazette, May 18, 1824, January 3, 1829, November 19, 1841, and November 29, 1838.

Alexandria Gazette, September 26, 1893. Additional information on the Carlsbad China Factory is at www.collectorscircle.com/bohemian/porcelain/factory_villages.html.

Alexandria Gazette, December 15, 1893.

Alexandria Gazette, March 4, 1826, May 5, 1829, December 12, 1845, September 16, 1853, August 22, 1860, and March 21, 1893.

Liberty Weekly Tribune, February 21, 1851, and April 14, 1854.

Alexandria Gazette, May 18, 1824, January 3, 1829, November 22, 1832, December 29, 1832, May 10, 1833, and July 31, 1833, November 11, 1833, September 21, 1838, and May 4, 1841. Flow-blue wares were advertised in the Alexandria Gazette on December 15, 1845, April 1, 1847, July 29, 1848, and September 23, 1848.

Alexandria Gazette, March 4, 1826, January 3, 1829, September 23, 1848, and February 15, 1854.

Alexandria Gazette, January 3, 1829, April 1, 1847, and September 23, 1848.

Liberty Weekly Tribune, February 21, 1851, November 5, 1852, October 23, 1853, and April 14, 1854.

Alexandria Gazette, August 13, 1838, and December 25, 1850.

Alexandria Gazette, August 13 and September 21, 1838; Liberty Weekly Tribune, July 27, August 10, and September 28, 1855, and May 16, 1856.

George L. Miller, “A Revised Set of CC Index Values for Classification and Economic Scaling of English Ceramics from 1787 to 1880,” Historical Archaeology 25, no. 1 (1991): 1–25.

Arnold A. Kowalsky and Dorothy E. Kowalsky, Encyclopedia of Marks on American, English, and European Earthenware, Ironstone, Stoneware, 1780–1980: Makers, Marks, and Patterns in Blue and White, Historic Blue, Flow Blue, Mulberry, Romantic Transferware, Tea Leaf and White Ironstones (Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer, 1999), pp. 658–60.

Amy C. Earls and George L. Miller, “Pottery News—Merchant Marks 2. Henderson Importers of New Orleans,” www.greatestjournal.com, August 10, 2004.