The Blue China wreck’s ceramic cargo on the ocean bottom under approximately 1,000 feet of water. (Photo, Odyssey Marine Exploration.)

Jar, Pearson and Company, Whittington Moor Potteries, near Chesterfield, England. Stoneware with Bristol glaze. Height not recorded. Mark: incised stamp, on shoulder, “Pearson & Co., Whittington Moor Potteries, near Chesterfield.” (Courtesy, Odyssey Marine Exploration.) The recovery of this jar by a fishing trawler ultimately led to the discovery of the Blue China wreck site.

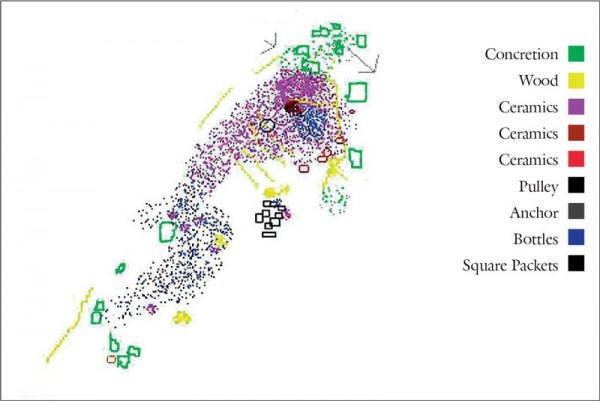

Schematic map of the Blue China wreck site showing the distribution of ceramics. (Courtesy, Odyssey Marine Exploration.)

Close-up of the cargo illustrated in fig. 1. The dishes shown here would have been closely packed in wooden crates or barrels that have since rotted away. (Photo, Odyssey Marine Exploration.)

Close-up showing the retrieval of a shell-edged plate using the robotic arm of a remotely operated vehicle known as the Ultimate ROV. (Photo, Odyssey Marine Exploration.)

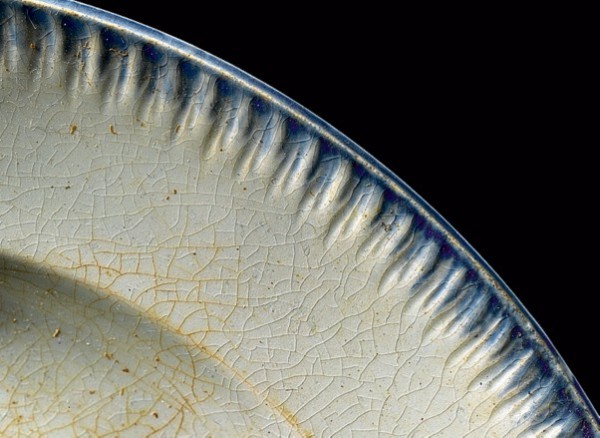

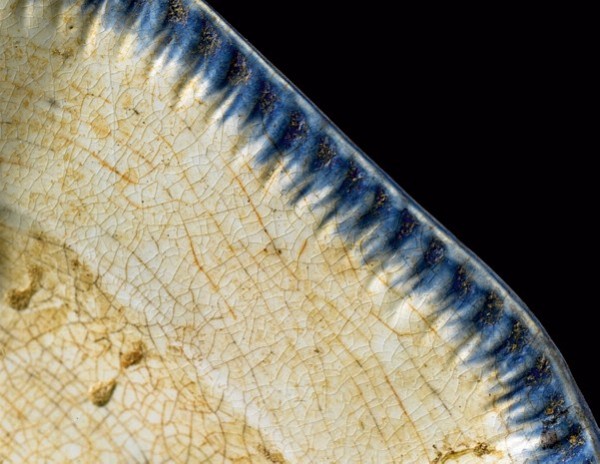

Plates, England, ca. 1845–1855. Whiteware. D. 9 7/16". (Unless otherwise noted, all artifact photography by Gavin Ashworth.) Two types of shell-edged plates were recovered whose impressed edge treatments and shades of cobalt blue differ slightly.

Detail of the rim of the plate illustrated at left in fig. 6.

Impressed “tally” marks from the shell-edged plates found in the Blue China wreck. These marks were used by potter workers to keep track of the vessels that came out of the kiln in good shape.

An impressed “5” from a shell-edged plate found in the Blue China wreck.

Soup plate, England, ca. 1845–1855. Whiteware. D. 10 1/2". This is one of the thirty-five shell-edged soup plates recovered from the Blue China wreck.

Detail of the rim of the soup plate illustrated in fig. 10.

Detail of the tally mark on the base of the soup plate illustrated in fig. 10.

Octagonal dishes, England, ca. 1845–1855. Whiteware. L. of largest 15 7/16". Sixteen of these shell-edged dishes were found, in three graduated sizes.

Detail of the rim of one of the dishes illustrated in fig. 13.

Detail of the impressed tally marks on the octagonal shell-edged dishes illustrated in fig. 13.

Bowls, England, ca. 1845–1855. Whiteware. D. of larger bowl 6 1/2". Thirty-five bowls with simple dipped decoration in the “London shape” were recovered from the wreck. Two sizes are shown here.

Jugs, England, ca. 1845–1855. Whiteware. H. of larger jug 7 3/4". Eight dipped decorated jugs were found in two basic sizes.

Jug and glass tumblers, England, ca. 1845–1855. Whiteware and glass. H. of jug 7 3/4". Five of the eight recovered dipped jugs contained clear glass tumblers. A sixth jug contained fragments of two green glass tumblers.

Mugs, England, ca. 1845–1855. Whiteware. H. of larger mug 4 5/8". Five dipped decorated cylindrical mugs were recovered from the wreck.

Mugs, England, ca. 1845–1855. Whiteware. H. of larger mug 4 1/2". Two of the dipped mugs are decorated with the so-called cat’s-eye slip technique.

Teabowl and saucer, England, ca. 1845–1855. Whiteware. D. of saucer 5 3/4". Twenty-six saucers and seventeen teabowls are painted in a simple floral pattern. The teabowls have a modified London shape.

Teabowl and saucer, England, ca. 1845–1855. Whiteware. D. of saucer 5 3/4".

Detail of the tally marks found on teabowls of the type illustrated in figs. 21 and 22.

Detail of the tally marks found on the saucers illustrated in figs. 21 and 22.

Cream jugs and covered sugar bowl, England, ca. 1845–1855. Whiteware. H. of jugs 4 7/16". Eight cream jugs and four sugar bowls were recovered among the painted teawares. The site yielded no evidence of teapots.

Plate, England, ca. 1850–1860. Whiteware. D. 9 3/8". A single example of this brown transfer-printed Asiatic Pheasants pattern was found. Asiatic Pheasants, among the most popular of nineteenth-century printed patterns, was used by numerous British firms.

Detail of the mark printed on the bottom of the plate illustrated in fig. 26. The Fedele Primavesi firm, active from 1850 to 1915, was located in Cardiff and Swansea, Wales, and specialized in the distribution of Welsh and Staffordshire pottery wares.

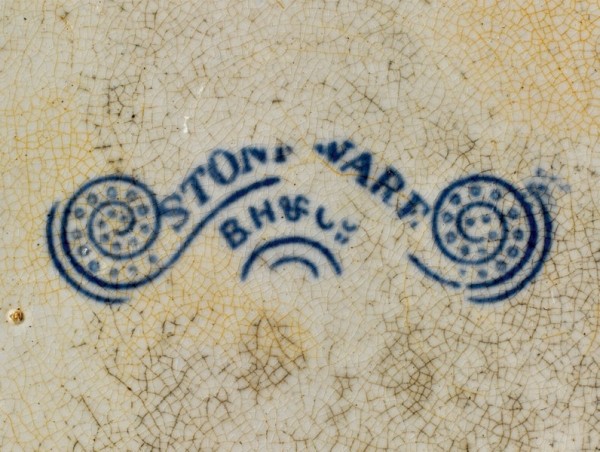

Plate, England, ca. 1845–1855. Whiteware. D. 9 3/8". This is the only example of the popular Blue Willow pattern plate found among the recovered ceramics.

Detail of the printed mark on the bottom of the plate illustrated in fig. 28. This mark represents the firm of Beech, Hancock and Company, which started production at the Swan Banks Works in Burslem in 1851. This suggests the earliest possible date for the wreck.

Sauceboat, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1850–1860. Whiteware. H. 3 9/16". The name of this light-blue pastoral pattern has yet to be identified.

Plate, England, ca. 1850–1860. Whiteware. D. 8 1/4". Three of these unmarked, molded dinner plates were recovered.

Bowls, England, ca. 1850–1860. Whiteware. H. of larger bowl 3 5/8". Fifteen of these plain bowls in the flaring London shape were found in two different sizes.

Detail of what is likely a size mark on the bottom of one of the bowls illustrated in fig. 32.

Chamberpots and basin, England, ca. 1850–1855. Whiteware. These plain but necessary toilet wares represent the least expensive ceramic ware of the period.

Salve jar, probably England, ca. 1850–1860. Whiteware. D. 3 3/16". Eleven bases and five covers from salve containers were recovered. Several of them still contain medicinal content, which has yet to be fully analyzed.

Bowl and mug, England, ca. 1850–1860. Whiteware and yellow ware. H. of mug 3". This yellow ware mug, shown next to one of the mocha bowls for comparison, was the only example recovered in the ceramic assemblage.

Chamber pot, England, ca. 1850–1860. Yellow ware. H. 5 3/8". The only decoration on this yellow chamber pot are five slip-trailed lines surrounding the body and rim.

Chamber pots, England, ca. 1850–1860. Yellow ware. H. 5 3/8". These two pots illustrate a blue dendritic mocha pattern applied vertically along a band of white slip.

Chamber pot, England, ca. 1850–1860. Yellow ware. H. 5 3/8". This yellow ware chamber pot has the blue dendritic mocha design applied in a horizontal band around the pot rather than a vertical one, as illustrated in fig. 38.

Ginger jars, Canton, China, ca. 1840–1860. Porcelain. H. 6 5/16". These blue-decorated ginger jars were common exports to England and America during the mid-nineteenth century.

Bottle, Europe, possibly Germany, ca. 1850. Stoneware. H. 11 1/8". Jugs of this type were used to hold a variety of fluids, ranging from seltzer water to ink.

Jug, probably New York, ca. 1850–1860. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13". This jug was the only identifiable American-made ceramic object found at the Blue China wreck site. It may have been either part of the cargo or for use by the crew.

During its search for the wreck of the side-wheel steamer Republic® in 2002, Odyssey Marine Exploration (Odyssey) discovered the sunken remains of an unidentified sailing vessel, a ship that had carried a substantial cargo of ceramic wares (fig. 1).[1] A small selection of artifacts from the site was recovered, and the wreck arrested in court, thus granting ownership to Odyssey.[2] The site was revisited by Odyssey in 2003 as part of an inspection of wrecks discovered near the remains of the Republic.[3] At that time it was observed that the site was undergoing destruction from the dragging of trawl nets across it—an ironic occurrence, since the site was discovered when a trawl net picked up an artifact. The decision was made to recover as many diagnostic artifacts as possible in an effort to identify and date the remains, and to recover as many intact ceramics as possible for study and exhibit before trawling destroyed the wreck site.[4]

The discovery of the wreck was precipitated by a single jar, an unexpected addition to a Florida trawlerman’s catch. The story of discovery of the glazed earthenware jar is unremarkable save for the fact that it had been brought to the surface of the Atlantic Ocean from more than one thousand feet down (fig. 2). The jar ultimately was brought to the attention of Odyssey, which surveyed the area and eventually designated it Site BA02. It slated the site to be investigated in more detail at a later time.

Site BA02 is located seventy nautical miles east-southeast of Jacksonville, Florida, at a depth of 367 meters in the Atlantic Ocean’s Gulf Stream current. Initial examination with acoustic imaging was conducted on July 11, 2002. The location was pinpointed, and on January 29, 2003, the wreck was examined visually using a remotely operated vehicle (ROV). At that time, three artifacts were removed: a bowl, a pitcher, and a glass tumbler found within the pitcher. These were recovered for the dual purpose of arresting the site in court and identifying and dating the vessel.

The shipwreck was named the “Blue China” wreck due to the presence of blue decoration on a number of the ceramics at the site. Even though later research revealed that this cargo consisted largely of earthenware—with very few items actually being “china” (i.e., Chinese porcelain or bone china)—by then the assigned name had become so firmly associated with the wreck that it was not changed.

On April 28, 2003, the wreck site was videotaped over the course of an eight-hour dive. At that time, three more artifacts—a large stoneware jug and two ceramic vases bearing blue ornamental designs—were placed in a recovery basket that had been deployed at the north end of the wreck mound. It was hoped that additional diagnostic artifacts would aid in dating and identifying the wreck. The next day the ROV shot more videotape of the site and retrieved the artifact recovery basket and its contents, bringing the total number of artifacts taken from the wreck to six.

It was observed that the site consisted of a large, low-lying mound, approximately 30 meters by 10 meters (98.42 feet by 32.80 feet). There appeared to be a large wooden hull structure in various stages of deterioration, with intact portions beneath a sand substrate. A large concentration of ceramics and bottles was situated near the south end of the site. At the extreme south end were two anchors, leading investigators to presume it was the bow end of the wreck. The examination quickly confirmed that the site was not the sought-after wreck of Republic but perhaps the remains of a merchant ship, possibly a coastal trader. Some displacement and damage to artifacts on the site were noted, reflecting disturbances wrought by modern fishing trawls.

In 2005, during a break from operations on Republic, the company’s research vessel Odyssey Explorer was sent to reexamine and assess the condition of other wrecks previously located in the vicinity. This included the Blue China wreck, which evidenced an alarming amount of additional destruction resulting from trawl nets being dragged over the site in the intervening period. Little of the original context remained undisturbed, and much of the substantial cargo of ceramics had been smashed and scattered. Odyssey Explorer’s mission had been only to check the status of the site during an interval of relative quiet in the midst of that season’s multiple hurricanes. Unfortunately, it was apparent that the site was in imminent danger of total destruction. The decision was made to use the brief window of fair weather to undertake what on land would be classed as a “salvage archaeology” operation—or, in this case, “rescue archaeology.” A photomosaic of the wreck was constructed, but time was too short to accommodate a measured site plan (fig. 3). The provenience data came from the use of the ship’s onboard transponder.

The wreck is that of a mixed-cargo merchant vessel, apparently of typical size for coastal and small-load transatlantic shipping. Vessels used in the China trade usually were larger-burthen ships used to carry much larger cargoes. While this does not rule out a ship coming from China or Asia, it suggests the ship was on a route that might have included the Caribbean islands or the Atlantic coastal trade.

No iron or stone ballast is visible on the site. The planking found beneath the silt under the artifacts is probably that of the very lowest part of the ship, so the recoverable items available from this wreck would be those described above, any additional items buried in the sediments on the wreck, and other items that might be buried on the surrounding sea floor. There is no evidence of another cargo hold, and there is no visible debris field surrounding the mound itself.

The various types of cargo seen on the wreck and recovered for study indicate this vessel was likely lost before the Civil War, probably 1850–1860. The few Chinese-made porcelain wares that have been recovered were mixed with large quantities of ceramics produced in English potteries and exported to the American market. Much of the glassware discovered, which has been fully reported on elsewhere, was probably produced at American glassworks in the mid-nineteenth century.[5]

General Description of the Vessel

The ship represented by the Blue China wreck was apparently a sailing vessel, as there is no visible evidence of machinery on the site. No wire rigging has been found, which supports a pre–Civil War time frame.[6] The absence of cannon suggests it was more likely a merchant than a military vessel—probably a coastal or, less likely, a transoceanic trading craft. Her hull and frame were both of wood, and she carried a small cargo consisting of different types of earthenware and glass bottles.

The one intact anchor suggests a vessel of one hundred tons or less. Unfortunately, because no complete and detailed measurements were made of the hull remains, little additional information regarding the size of the ship can be deduced. Some rough dimensions can be scaled off the photomosaic. The length of the visible hull remains is approximately 57.7 feet, which is probably the approximate keel length. The breadth of the visible hull remains is approximately 14 feet. Also obtained from the photomosaic are scaled measurements from exposed frames near the middle of the wreckage. The sided dimension of the visible portions ranges 4.7–5.5 inches, with a space of 4.3 inches between adjacent frames. According to the 1865 American Lloyd’s Register of American and Foreign Shipping, the Rule VIII minimum requirements for a vessel of one hundred tons are floors of 9 inches and frames measuring 4.5 inches at the plank sheer and 8 inches at the throat.[7] The available information on this vessel, then, suggests it was a small one, probably under one hundred tons.

An additional clue to the size of the original vessel was sought from the remains of what is believed to be one of the hawse pipes. The inner diameter of this piece was measured at 4 inches, which figure provides an approximation of the maximum size anchor cable used for the vessel.[8] In describing the construction of a model of Cruiser, a two-masted sloop of 1752, Ron McCarthy gives a formula for calculating the necessary diameter of a hawse hole:

The size of the opening was relative to the size of the cable that passed through it. The cable was a manufactured item which came in standard sizes, so the formula which was used for the size of cable required for any given vessel would need to be rounded up or down to suit the size of cable available. The formula to arrive at the size of cable required was that the circumference of the cable in inches was half the full breadth of the ship.[9]

Once the diameter of the cable required had been determined, the size (diameter) of the hawse hole was 9/4 of that number. Working back from the 4-inch diameter of the hawse hole on the Blue China wreck, the formula yields a value of the breadth of the ship—in this case, 11.2 feet, which is far too small to be realistic. Evidently a formula for Royal Navy ships cannot be applied to a merchant vessel more than one hundred years later.

General Cargo

The diverse quality and type of cargo initially suggested a modest coastal trader—most likely an American merchant’s vessel—carrying goods on established routes to fill customer orders along the Atlantic coast, or perhaps in the Caribbean.[10] The ceramic wares recovered from the site, which were largely British-made, would have been shipped first to major American ports such as New York and Boston. Merchants there imported English and Chinese ceramics, which they repacked and shipped down the coast for resale to other merchants or smaller distributors.

Ownership and nationality of the vessel are unknown, and likely will remain so in the absence of more diagnostic materials. A transoceanic trader could have originated in the Caribbean, China, England, Holland, Mexico, South America, Spain, or Sweden. However, as a coastal trader (the most likely scenario), it probably originated from a port on the North Atlantic seaboard.

The most noticeable artifacts on the site are in the concentration of ceramics discovered at the south (bow) end of the wreck: circular plates, octagonal platters, dishes, bowls, teabowls (teacups), saucers, creamers, sugar bowls, pitchers, mugs, jars, chamber pots, and wash basins (fig. 4). A sample of the visible ceramics was retrieved from the ocean bottom and are discussed below (fig. 5).

British Shell-edged Earthenware

The largest concentration of earthenware on board the vessel was British shell-edged flatware—soup bowls, plates, platters—recognized as “the most popular and long-lived style ever produced by the English ceramics industry.”[11] The large quantity recovered indicates this dinnerware was part of the cargo and not just for the use of the ship’s crew.

Initially marketed for upper-middle-class families, British shell-edged ware was produced and exported in such large quantities between the years 1780 and 1860 that it seems to have been used in almost every household in America. Fragments of shell-edged ceramics have been unearthed from most archaeological sites of this period, regardless of socioeconomic class.

The records of Staffordshire potters document the vast quantities of shell-edged wares made for the British market as well as for export to many countries. And the surviving invoices of American merchants show that shell-edged wares account for more than forty percent of the tablewares sold in America between 1783 and 1858.[12] As George Miller and Robert Hunter have shown, shell-edged wares can be dated by tracing the evolution of the rim shape and design. The earliest shape, fashionable between 1775 and 1800, was an asymmetrical, undulating scallop with impressed curved lines. By about 1800 the scallops of the shell edge had become even and symmetrical; tableware in this style was produced in blue or green shell edges and was made almost exclusively of pearlware until well into the 1830s. By the 1840s heavy whiteware replaced the pearlware and, to cut costs, impressed lines typically colored blue were used instead of the scalloped rim. By the 1860s the impressed lines had been eliminated and the shell edge was simulated with painted underglaze blue. Those last two decades saw a decline in the quality and variety of manufacture, to the point where shell-edged ware became an everyday, generic utilitarian ware.

The shell-edged examples recovered from the Blue China wreck are heavy whiteware with impressed lines colored blue, indicative of the later period in which these wares were produced (1840s–1850s), and were made from fairly new crisp molds.[13] Most bear on their underside an impressed stamp—an encircled floral-like design with dots or, in a few cases, a variant (fig. 8).[14]

One hundred and two dinner plates were recovered (figs. 6, 7). Two general shades of blue applied over the shell-edged border were noted in the assemblage ranging from a medium blue to a very dark blue. Eighty of the plates bore the impressed mark mentioned above; eleven feature an impressed “5” (fig. 9).

Also among the shell-edged assemblage were thirty-five soup plates 10 1/2 inches in diameter (fig. 10), all of which have the darker cobalt blue border (fig. 11). Twenty-nine bear a tally mark on the bottom, four have a variant of the tally mark, one has a mark that is too illegible to declare it a tally mark, and one has no mark at all (fig. 12).

Sixteen octagonal serving dishes (fig. 13) were found: six are 13 1/2 inches long, five are 14 5/16 inches, and five are 15 7/16 inches. All have a dark cobalt blue rim (fig. 14). Most of the platters bear an impressed number on the underside (fig. 15): the small with a “12”; the medium with a “13”; and the largest with a “14.” Such impressed numbers on plates and platters typically relate to the size of the items designated in inches; in this case, however, the numbers, while they do indicate graduated sizes, are not precise correlates in measure. One small and one medium platter have a tally mark in the form of a pinwheel blossom with triangular petals (see fig. 15, far left).

Dipped Wares

Second in quantity of ceramics found at the site is the British-made slip-decorated earthenware, which in the period was known as dipped ware and today is often referred to more generically as mochaware. First produced by Staffordshire potters in the late eighteenth century, these generic whitewares enjoyed a long period of popularity. By the mid-nineteenth century they had a thicker, heavier body and a less elegant appearance than those of 1790–1830s. Slip-decorated wares were the least expensive imported decorated earthenware available in North America.[15]

A number of features related to changes that took place in the mid-nineteenth century confirms the date (1850–1860) of the dipped wares found in the wreck. One was a reduction in color choices. Originally slips were colored with a variety of earth colorants: iron oxide produced reds and rusts, browns, and black; cobalt oxide produced blue, copper oxide green, and antimony and uranium yellow. The lead glaze that vitrified the objects also enhanced those earth colors. When the health risks to the potters using many of these dangerous substances became known, the materials gradually became obsolete. As a result, the colors found on dipped wares of the second half of the nineteenth century are predominantly black, blue, gray, and white, and lack the earlier vitality. The mid-nineteenth-century slipware also had fewer decorative features than those used in earlier times. The need for speed demanded by price competition eliminated most slip decoration beyond the banded and dendritic patterns.[16]

Of the thirty-five bowls recovered from the site, which were found in six sizes, some have a cream ground with a tan band enclosed by double narrow brown bands raised on a ring foot, others have a gray-tan band, and two of the bowls have a cream ground with a wide brown band enclosed by double narrow brown bands. The heights range from 3 to 3 5/8 inches and the diameters from about 5 1/2 to 6 1/2 inches (fig. 16).

Also retrieved were eight dipped jugs with a baluster form, shaped spout, molded handle with foliate terminals, and a molded base (fig. 17). All are unmarked and all have identical decoration—a wide, blue-gray central band flanked by two brighter blue bands. Eight narrow brown slip lines define the boundaries of these larger bands. Four different sizes are recorded, with heights ranging from 6 1/4 inches to 7 3/4 inches.

One of the most interesting discoveries was that five of the jugs contained a clear glass tumbler; a sixth contained fragments of two green glass tumblers (fig. 18). This suggests a packing strategy that maximized all available space within the ceramic cargo.

Five dipped mugs with applied molded handle and stepped base were also found. Their heights, which range from 3 inches to 4 11/16 inches, correspond to one-half and one full pint capacities. Three of the mugs are decorated with some combination of wide blue and/or gray bands in combination with four, six, or eight brown stripes (fig. 19). No maker’s marks have been detected. One of the mugs has a cream ground with blue bands and is decorated with a cat’s-eye pattern below a blue-and-cream band separated by six narrow brown bands (fig. 20). Another features the cat’s-eye decoration enclosed by double narrow brown bands.

Painted Wares

In all of the sixty-four pieces, only four different examples of hand-painted floral motifs were recovered. Based on the quantity found, these painted wares were likely a part of the cargo. They have been identified as elements of a tea set, and include teabowls (i.e., cups), creamers, and sugar bowls. No teapots were recovered or observed. The isolated painted floral decoration on these ceramics is sometimes referred to as “sprig,” although it is best to refer to these wares simply as “painted,” the terms used by the potters and merchants of the time.[17]

Twenty-six saucers having a diameter of 5 3/4 inches and seventeen London-shaped teabowls were in the assemblage. At least two different floral decorations are represented: full bloom roses with green leaves, and sprays in cobalt blue, green, and red (figs. 21, 22). Four different impressed marks were found in this group of artifacts (figs. 23, 24) and are probably tally marks for the workers to be paid if the vessels came out of the kiln in good shape.[18] These tally marks do not help identify a particular manufacturer as similar marks were used at different factories.

Included among these painted teawares were eight cream jugs and four sugar bowls, as well as one sugar-bowl lid (fig. 25). Two different designs are present on the creamware jugs: red berries and green leaves with a painted black asymmetrical stripe on the ear-shaped handle; and, on one example, green leaves and a blue tulip with a painted black asymmetrical stripe on the extruded handle. The four painted sugar bowls were found in two different sizes, one with a height of 3 1/4 inches and one with a height of 4 1/4 inches.

Transfer-printed Wares

Only three examples of transfer-printed wares—two circular plates and a gravy boat—were recovered from the shipwreck. One of the plates is decorated with an elaborate bird-and-flower motif known as Asiatic Pheasants (fig. 26), which was one of the most popular dinnerware patterns of the Victorian era and is still produced in Staffordshire today. The Staffordshire town most associated with it is Tunstall, where from about 1838 to 1939 the pattern was in continuous production by pottery firms at a number of locations, including the Well Street, Swan Bank, Unicorn, and Pinnocks works. The pattern is known to have been copied by several potteries along the Clyde in Scotland, the Tyne and Tees in Northumberland, in Yorkshire, London, Devon and South Wales.[19]

On the reverse of the example recovered from the Blue China wreck is the large mark “F. PRIMAVESI / & SONS / CARDIFF” (fig. 27). Fedele Primavesi’s firm, located in Cardiff and Swansea, Wales, was active from 1850 to 1915 and specialized in the resale of Welsh and Staffordshire pottery wares. Pottery agents or dealers such as Fedele Primavesi served as middlemen between the potteries and the china retailers or warehouses. In this case, the Primavesi company mark was applied by the manufacturing pottery.

Another plate, decorated in the standard Willow pattern (fig. 28), bears a maker’s mark (fig. 29) containing the words “STONE WARE / B H & CO.” This mark was identified as a mark of Beech, Hancock and Company, a Staffordshire pottery whose earliest partnerships was recorded at Burslem in 1851, when it started production at the Swan Banks Works in Burslem.[20] Research indicates the “B H & CO” mark was employed from 1851 to 1855, confirming the earliest possible date for the wreck. The company continued operating potteries in Tunstall from 1857 to 1876, at which point the Hancock partnership ended. The firm continued to trade as James Beech until 1889, when it was taken over by Boulton, Machin and Tennant.

An earthenware sauce- or gravy boat was also retrieved, printed with a light blue design on a white ground depicting cows in a country setting (fig. 30). The name of the pattern has yet to be identified but is similar to the pastoral genre produced during this time. The handle is broken off and there is no tally or maker’s mark.

Undecorated Whiteware

Five different types of undecorated whiteware vessels were recovered from the site: three plates, fifteen bowls, five chamber pots, four wash basins, and eleven salve jars with five lids. Whiteware is a heavy, thick-bodied, utilitarian ceramic that the British first exported to America in the 1840s. These items are most likely cargo, as they were found with the bulk of the ceramics at the bow end of the site; sturdy, utilitarian ironstone wares were also used on a ship of this period, however.

The three molded dinner plates have a diameter of 8 1/4 inches (fig. 31) and bear no identifiable marks.

The bowls, which have flared sides and rest on a pronounced ring foot, range in diameter from 5 5/8 to 6 3/8 inches, reflecting two different sizes with some limited size variation (fig. 32). Thirteen of the fifteen bowls bear no tally or maker’s marks; one has a possible mark, although it is too illegible to be certain; and one has a gouge. Two of the bowls bear the number “18” (fig. 33), which possibly represents a size designation typically used to denote a potter’s dozen.[21]

The five undecorated whiteware chamber pots differ slightly in size (fig. 34). Each has an applied handle with a leaf terminal and a standing footring. No tally or maker’s marks are visible on any of the chamber pots or the four undecorated wash basins.

Three of the eleven salve jars contain a salve or greaselike substance, possibly cosmetic or medicinal in nature (fig. 35).

Yellow Earthenware

Also recovered from the site were two types of vessels made of yellow earthenware: one mug and five chamber pots. Yellow ware was produced by British immigrant potters who had established a number of potteries in the United States in the 1830s. Given the predominance of British ceramics carried on the ship, however, these yellow wares were probably made in England, most likely in the Derbyshire region known for yellow-bodied wares.[22]

The slip decoration on the yellow ware mug consists of four thin brown stripes, two at the top and two at the bottom (fig. 36). The handle has broken off and no tally or maker’s mark is present.

Of the five yellow ware chamber pots recovered, four carry slip decoration. All have an applied molded handle and are raised on a ring foot, and all are without maker’s or tally marks. One of the chamber pots is unadorned save for a series of thin blue lines circling the body of the vessel (fig. 37). Three others are decorated with thin blue lines and a wide white band over which is a blue “dendritic” or treelike decoration (fig. 38). The last chamber pot is similar to the previous three except that the design is rotated at right angles to the original pattern (fig. 39).

Canton Ginger Jars

Only four intact examples of Chinese porcelain ginger jars of the so-called Canton type were recovered, each measuring 6 5/16 inches in height (fig. 40). All four are missing their lids and date to the first half of the nineteenth century. The name “ginger jar” comes from the fact that similar containers were used for the export of large quantities of crystallized ginger (as well as other pickled food items) from China.[23] Such containers were a popular export to Europe and America for much of the nineteenth century. The hand-painted underglaze-blue decoration features a house by the water with a man fishing and a sailing boat. The outline of the embellishment is drawn with light and heavy blue lines and the color is washed to lighter shades to contrast with the white porcelain.

Stoneware

Three stoneware vessels were recovered from the site. The first is a tall, cylindrical pouring jug, approximately 11 1/8 inches in height, that might represent either cargo or ship’s stores (fig. 41). This unmarked artifact is similar to other marked examples from the latter half of the nineteenth century known to have been used to hold various fluids that were better stored in dark, cool environments: seltzer water, sarsaparilla, wine, beer, vinegar, cider, oil, molasses, even ink. The origin of this jug is unknown, but the bottle style is similar to other stoneware jugs that usually have foreign pottery and/or company marks, most often from Denmark, England, Germany, and Sweden—all of which stored the variety of fluids mentioned above.

The original artifact that ultimately led to the recovery of the vessel is an English jar with a so-called Bristol glaze (see fig. 2). It bears the incised stamp of “Pearson & Co., Whittington Moor Potteries, near Chesterfield.” Chesterfield was well known for its many potteries, and James Pearson established a pottery around 1810 at Whittington Moor that continued to operate until the 1980s. This type of glaze was developed in Bristol, England, about 1835 and began to be used by American stoneware potters not long after, soon replacing much of the brown salt-glazed stoneware that was used for utilitarian purposes.[24] To create the two-toned effect, bottles are typically dipped twice vertically, with off-white on the top or bottom half, and mustard on the other. As a result, the Bristol glaze is sometimes called “double glazed.” Bristol-glazed wares are most commonly reported in bottle forms from American archaeological sites; the glaze is also found on stoneware crocks, jars, and other utilitarian items.

The only conclusively ceramic object of American manufacture retrieved from the wreck is an elongated ovoid salt-glazed stoneware jug with a height of 13 inches (fig. 42). The jug is devoid of decoration with the exception of cobalt highlights at the handle terminal. Jugs of this type were produced in large quantities in northeastern United States (Pennsylvania or New York) in the middle of the nineteenth century.[25] They were used for many types of liquids that were stored in bulk, such as wine, water, rum, vinegar, oil, and so forth. While the contents of this jug may have been part of the cargo, it more likely was a serviceable shipboard vessel.

Conclusion

The ceramics recovered from the Blue China wreck present a unique opportunity to study the makeup of a British-made ceramic cargo carried by an American coastal trader in the mid-nineteenth century. The ceramic evidence suggests a date for the wreck between 1851 and probably 1860 at the latest, which is consistent with evidence from other artifacts recovered from the site and the ship’s construction. The Blue China wreck cargo provides direct documentation of mid-nineteenth-century purchasing and manufacturing patterns, which segregated ceramics into categories of teaware, tableware, and kitchenware.

As George Miller has suggested, while some of these functional wares were available both undecorated (CC) and transfer printed, the decorative types were almost always limited to wares of a particular function.[26] For example, shell-edged wares were tableware; painted wares were primarily teaware; and dipped wares were limited to hollow wares such as bowls, mugs, jugs, and chamber pots. Such cargoes are hinted at in shipping records of the period, but few of these assemblages have survived intact. The most notable American example was the excavation of the steamboat Arabia, which sank in the Missouri River in 1856.[27] Excavation of the wreck began in 1988 and has yielded hundreds of examples from the ceramic cargo found still intact within the bottom hull. Comparison of this assemblage with that found in the Blue China wreck offers some preliminary insights into the makeup of period ceramic cargoes.

The teawares aboard the Blue China wreck are represented by sixty-four floral painted examples. As seen elsewhere, ceramic teas constitute a significantly greater proportion of decorated ware than do plates and bowls.[28] The majority were teabowls and saucers, with eight cream jugs and four sugar bowls. No evidence of teapots was recovered, although one would certainly expect these items to be included in such shipments. Among the unmarked floral teawares recovered from the Arabia was a single teapot among twenty cups and five saucers.[29]

Most of the tablewares recovered from the Blue China wreck are represented in shell-edged dinner plates, soup plates, and octagonal dishes. The totals and proportions are very similar to what was found aboard the Arabia. Whereas the Blue China wreck has 102 dinner plates, 35 soup plates, and 16 octagonal dishes, the Arabia has 69 plates, 11 “bowls” (probably soups), and 26 octagonal platters (dishes). Eleven shell-edged casserole or servicing dishes were also among the Arabia cargo. The few transfer-printed plates found on the Blue China wreck may hint at the presence of a large grouping of decorated tablewares not found during the recovery efforts. Evidence from both wrecks suggests that the blue shell-edged whitewares were the main staple of mid-nineteenth-century tablewares for the average American consumer household.

Included in the kitchenware category from the Blue China wreck were thirty-five dipped bowls and eight dipped jugs. This type of decoration has a long history of production, beginning in the nineteenth century, for general food preparation and serving. By the 1850s production of dipped decoration was in decline, superseded by the less expensive whitewares. No dipped wares were found in the Arabia cargo, which suggests some sort of difference either in consumer preference and/or costs. It is also possible that the presence of so many dipped wares found in the Blue China wreck could date it closer to the 1851 date, as the Arabia sank in 1856 and seemed to have a large quantity of the much more fashionable white ironstone of the period. Fifteen undecorated whiteware bowls from the Blue China wreck can also be included in this kitchenware category.

Several ceramic objects classified as toilet ware were in the assemblage from the Blue China wreck, including five yellow ware chamber pots, five undecorated whiteware chamber pots, and four whiteware wash basins. In contrast, only a single white ironstone chamber pot was recovered from the Arabia.

The ultimate research value of the ceramic cargo from the Blue China wreck awaits comparison with other published ceramics dating from this period by ceramic scholars and historical archaeologists. The opportunity to recover and document this assemblage was certainly an important first step in providing a glimpse into a mid-nineteenth-century cargo that would have been unattainable except through rudimentary documents. As new technology now provides access to the deepest wrecks, exciting new discoveries will continue to add to our cumulative knowledge of Anglo-American ceramic history.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Robert Hunter, Gavin Ashworth, J. Byron Dille, George Miller, William Sargent, Jonathan Rickard, Jane Spillman, and Jill Yakubik.

®SS Republic is a registered trademark of Odyssey Marine Exploration, Inc.

“Arresting” a wreck site refers to a legal process that provides, in this case, Odyssey with priority salvage status for a specific shipwreck and cargo. Odyssey’s recent arrest complaints were filed in the United States District Court for the Middle District of Florida, the first step in establishing Odyssey’s exclusive access to the sites under protection of the federal admiralty courts. Once the arrest process is completed, Odyssey will be deemed the sole salvor, with exclusive access to the sites. After recovery, a percentage of the artifacts will be awarded to Odyssey by the court in a final salvage award.

The Republic shipwreck was featured in the October 2004 issue of National Geographic.

This article is adapted from the larger site report by Hawk Tolson, Ellen Gerth, and Neil Cunningham Dobson, “Artifacts from the Blue China Wreck: An Unknown Shipwreck of the Coast of Jacksonville, Florida,” Odyessy Marine Exploration, Tampa, Fla., 2007.

Ibid.

Larry E. Murphy, Dry Tortugas National Park: Submerged Cultural Resources Assessment (Santa Fe, N.Mex.: Submerged Cultural Resources Unit, National Park Service, 1993), p. 204.

Mystic Seaport Museum, “1865: American Lloyd’s Register of American and Foreign Shipping,” p. xv. Available online at G. W. Blunt White Library; www.mysticseaport.org/library/initiative/ShipRegister.cfm?BibID=237571865 (accessed July 2, 2008).

Wyatt Yeager, personal communication, October 19, 2005.

Ron McCarthy, Building Plank-on-Frame Ship Models (London: Conway Maritime Press, 1994), pp. 80–81.

Odyssey Marine Exploration, “Research Report,” May 18, 2005.

Robert R. Hunter Jr. and George L. Miller, “English Shell-edged Earthenware,” Antiques 145 (March 1994): 432–43.

George L. Miller and Robert R. Hunter Jr., “English Shell-edged Earthenware: Alias Leeds Ware, Alias Feather Edge,” in The Consumer Revolution in 18th Century English Pottery, Proceedings of the Wedgwood International Seminar, no. 35 (n.p.: Wedgwood International Seminar, 1990), pp. 107–36; and Hunter and Miller, “English Shell-edged Earthenware.”

When molds become worn, it is much more difficult to see the pattern, especially when it is filled with glaze and heavy use of the blue color. George Miller, personal communication, August 21, 2007.

Frank Burchill and Richard Ross, A History of the Potter’s Union (Hanley: Stoke-on-Trent Ceramic and Allied Trades Union, 1977).

George L. Miller, “A Revised Set of CC Index Values for Classification and Economic Scaling of English Ceramics from 1787 to 1880,” Historical Archaeology 25, no. 1 (1991): 1–25.

Jonathan Rickard, Mocha and Related Dipped Wares, 1770–1939 (Lebanon, N.H.: University Press of New England in association with Historic Eastfield Foundation, 2006).

George L. Miller and Amy Earls, “War and Pots,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Suffolk, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club for the Chipstone Foundation, 2008), pp. 95.

Miller, “A Revised Set of CC Index Values.”

See www.asiaticpheasants.co.uk/newpatthist.html (accessed July 2, 2008).

See www.asiaticpheasants.co.uk/Makers/Beech%20Partnerships.html (accessed July 2, 2008).

Miller, “A Revised Set of CC Index Values.”

Joan Leibowitz, Yellow Ware: The Transitional Ceramic (Exton, Pa.: Schiffer Publishing, 1985), pp. 90–108; and John Gallo, Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Yellow Ware (Oneonta, N.Y.: John Gallo, 1985), pp. 10–17.

William Sargent, personal communication, March 6, 2003. Miller’s Chinese and Japanese Antiques: Buyer’s Guide, edited by Peter Wain and Jo Wood (London: Miller’s, 1999).

Georgeanna H. Greer, American Stonewares: The Art and Craft of Utilitarian Potters (Exton, Pa.: Schiffer, 1981); Ivor Noël Hume, If These Pots Could Talk: Collecting 2,000 Years of British Household Pottery (Milwaukee, Wis.: Chipstone Foundation, 2001), p. 324.

William C. Ketchum, Potters and Potteries of New York State, 1650–1900, 2nd ed. (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1987).

See Miller and Earls, “War and Pots,” p. 83.

Greg Hawley, Treasure in a Cornfield (Kansas City, Mo.: Paddle Wheel Publishing, 1998).

Miller and Earls, “War and Pots,” pp. 86–87, and Table 6.

Ibid., p. 205.