Norwalk Pottery/Smith Pottery site. (Courtesy, Norwalk Museum.) This picture was taken in November 1901 from the west side of the Norwalk River.

Norwalk Pottery/Smith Pottery, ca. 1900. (Courtesy, Norwalk Museum.) This picture was taken from the west side of the Norwalk River, from a position slightly north of that shown in fig. 1.

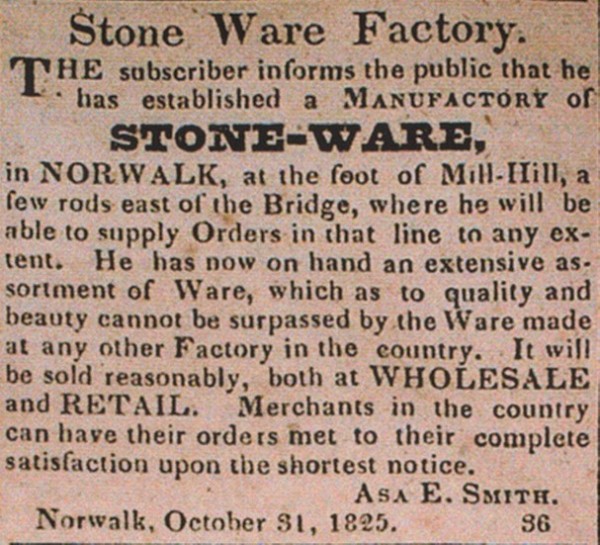

Advertisement placed in the Norwalk Gazette on October 31, 1825. (Courtesy, Norwalk Museum.) This ad is the first public announcement of the opening of Asa E. Smith’s pottery company.

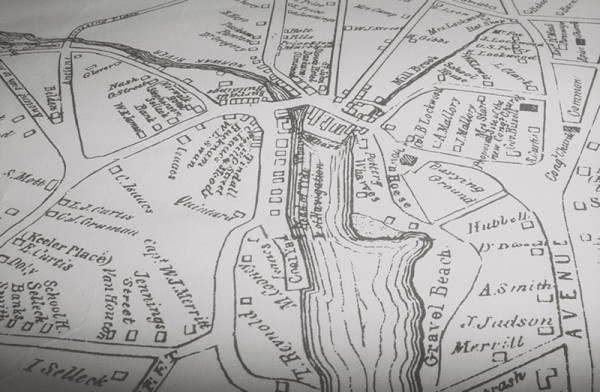

Detail from “The Principal Parts of Norwalk in the Year 1847, with a Plan of the Ancient Settlement,” a map by Edwin Hall. (Courtesy of the author.) This 1847 map shows the pottery wharves on the east side of the river, at the head of the harbor.

John Warner Barber, South View of the Borough of Norwalk, 1836. Engraving. (Courtesy of the author.) The pottery building can be seen on the waterfront, directly to the right of the ship’s sail.

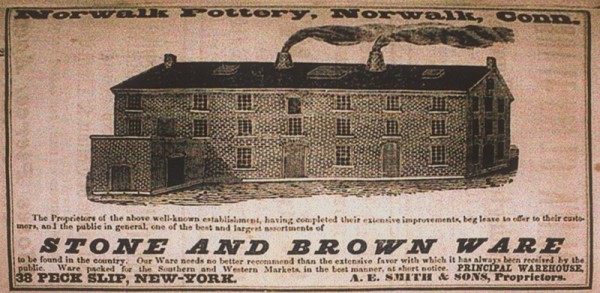

Advertisement for “STONE AND BROWN WARE” produced by the Norwalk Pottery, A. E. Smith & Sons, Proprietors. Reproduced in Connecticut Business Directory: Containing the Name, Location and Business of the Principal Manufacturing Establishments, Mercantile Firms, &c., for the Year 1851 (New Haven, Conn.: J. H. Benham, 1951), p. 249. (Courtesy of the author.)

This 1905 addition, built in a style similar to the original pottery building, was situated at the south end of the property. (Photo by the author, 1997.)

This east portion of the building along the millrace was part of the 1905 addition. (Unless otherwise noted, all photos of the pottery building were taken by the author in 2004.)

View along the millrace after demolition. The building in the rear was the former Phoenix Block. The area between the water and the retaining wall was littered with sherds, and some were mixed in the cement of the retaining wall.

This photo was taken after the first stage of demolition, in which a 1905 addition had been removed. The white area to the right is approximately where the south wall of the pottery had been.

Most of the original pottery building remained intact over the years and was either added to or built around. Shown here is the original west wall of the pottery manufactory.

Demolition of the northeast corner of the building exposes one of its lives as a nightclub.

Exposure of an interior wall, approximately mid-span, reveals support columns and beam pockets.

A close-up of the view illustrated in fig. 13, taken facing west.

The final remains of the Norwalk Pottery/Smith Pottery. Much of this area was backfilled with sherds from the pottery’s waster dump. The cement floor, also part of the 1905 addition, might be hiding a wealth of information.

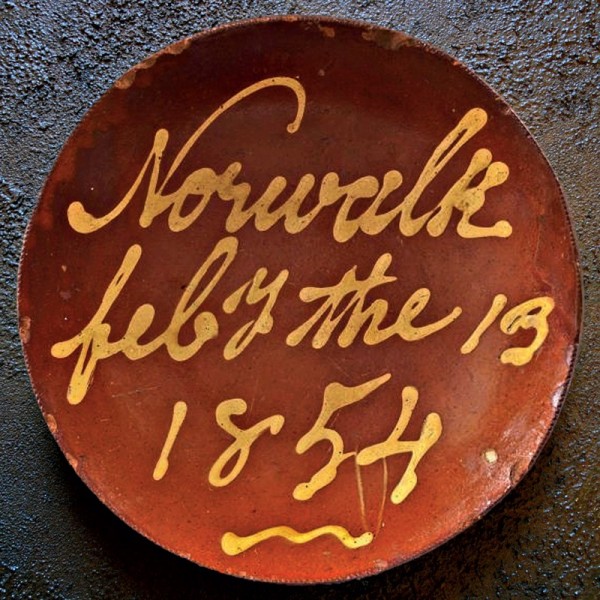

Plate, Norwalk, Connecticut, 1854. Slipware. D. 12 3/8". Inscribed on front: “Norwalk / feby the 13 / 1854” (Courtesy, Collection of the Norwalk Historical Society; photo, Richard Ventre.)

From the latter part of the eighteenth century into the early twentieth century, Norwalk, Connecticut, was an important center for the manufacture of pottery. The Asa E. Smith Pottery Company, located near Wall and East Wall Streets and in business from 1825 until approximately 1888, was one of the largest in New England (figs. 1, 2). It employed about fifty men and owned two schooners, which brought raw materials to the site and transported finished products to ports along the eastern seaboard. In 1888 the business apparently was sold to James and Charles Lycett, who continued to make pottery at its location until about 1897, when a group of Norwalk businessmen formed the Norwalk Pottery Company and appointed Howard Hobart Smith, son of Asa E. Smith, as agent for the company. The Norwalk Pottery Company continued in business until 1905, when the property was sold to and the building expanded by the St. George Pulp and Paper Company. It eventually landed in the hands of a local family. Over the years the buildings fell into disrepair, eventually becoming an eyesore and a hazard. They were finally condemned by this picturesque waterside town and in September 2004 monster machines destroyed them, bringing an ignominious end to a dynasty.[1]

I was familiar with the site. In November 1997, while in Norwalk on business, I spotted a building that resembled the one depicted in the frontispiece to Norwalk Potteries by Andrew L. and Kate Barber Winston. When I asked the man with whom I was doing business about the building and he replied, “That’s the old pottery building,” I nearly jumped out of my skin. For years I had collected the redware and stoneware for which the Smith pottery is famous, yet I had no idea the pottery buildings still stood—and only fifteen minutes from my home! Could it be true? The next day, armed with a camera and my copy of Norwalk Potteries, I wandered about the crumbling old ruin and took countless pictures.

The following week, with knowledgeable friend Bill Ketchum in tow, I revisited the site. We examined the structure from every possible angle and I presented the pictures and the publication to Bill in the manner of a lawyer presenting evidence for trial. Since neither of us was aware of any mention of Asa Smith’s building in the current histories of the Norwalk potting industry, we remained cautious. A good deal more study was required before we could confirm our hypothesis.

I went to the Norwalk Town Clerk’s office and began to research the property. To my surprise and delight, all of the information I needed was available, and in a matter of hours I had conclusive proof that our red-bricked antiquity was, indeed, the Smith pottery factory. Yet there was so much more to learn, and I spent almost eight years researching the pottery’s story.

Asa E. Smith had received his training from his uncle, Absalom Day, a master potter originally from New Jersey. On October 31, 1825, Smith ran a newspaper advertisement in the Norwalk Gazette (fig. 3) announcing the establishment of his own enterprise:

Stone Ware Factory.

THE subscriber informs the public that he has established a MANUFACTORY ofSTONE-WARE

in NORWALK, at the foot of Mill-Hill, a few rods east of the Bridge, where he will be able to supply Orders in that line to any extent. He has now on hand an extensive assortment of Ware, which as to quality and beauty cannot be surpassed by the Ware made at any other Factory in the country. It will be sold reasonably, both at WHOLESALE and RETAIL. Merchants in the country can have their orders met to their complete satisfaction upon the shortest notice.

ASA E. SMITH

Norwalk, October 31, 1825.

Although it is obvious that at the time of this announcement Smith was firmly entrenched in business, the exact date of the pottery’s construction is not known (fig. 4). However, an engraving in John Warner Barber’s 1836 Historical Collections of Connecticut includes what is believed to be the pottery, located at the head of Norwalk Harbor (fig. 5).[2] The artist’s rendering of the building closely resembles pictures featured on Smith’s price list and in the 1851 Connecticut Business Directory (fig. 6).[3] It seems safe, then, to date the building at least as far back as 1836, and possibly even to 1825, when the advertisement touting the pottery’s opening was published. In any event, the building had survived since the second quarter of the nineteenth century.

For fifty-two years Smith and his relatives and offspring ran a successful pottery at this location. Various markings found on extant pottery pieces produced at this location (“A. E. Smith—Norwalk” is the most rare) indicate the various years of production and partnership throughout the history of the business.

As we now know from the history of various New England pottery factories, however, utilitarian pottery was about to go the way of the dinosaur. Potters living in states to the south and west, such as New Jersey and Ohio, had clay sources on their doorstep, freeing them of the expense of importing. Moreover, new technology in the manufacture of glass and tin meant that products made of those materials were much more affordable.

By 1877 Smith’s business had failed, winding up in bankruptcy. The family had been unable both to make the transition into more modern manufacturing and to adapt to alternative products. A decade later, several businessmen in Norwalk decided to continue the pottery tradition using the Smith building and equipment. In 1888 they pooled their resources and founded the Norwalk Pottery Company, hiring young Asa E. Smith Jr. and another experienced potter, Enoch Wood, to oversee operations. Claiming in a newspaper advertisement that “success was guaranteed,” they sold shares in the business to the public. The optimism was short-lived, however. By now Americans were much more excited by glamour than by utility.

Although Howard Hobart Smith had joined ranks with the Norwalk Pottery Company as an agent, by then the company was apparently in its worst period of decline. It is not clear how much production was being carried out at the plant, but no one was able to operate the business successfully for long.

According to family tradition, the mill operated since 1905 by the St. George Pulp and Paper Company was finally bought and closed by a New York newspaper syndicate, which also sold off the equipment. The building remained idle ever since, although the property changed hands in 1937, when it was purchased by Norwalk Realties Company, which sold it to a private owner. The property stayed in that family until the summer of 2004, when it was sold to a developer.

In early July 2004 it became apparent that the site was being scheduled for development and that the pottery building would be torn down, but it was equally apparent that it was too late to make a stand to protect it. Nonetheless, amid the usual flurry of rumors and confusion, preservationists scrambled to figure out what, if anything, could be done.

The first logical step was to determine whether the building was listed as a historic property, or was eligible for such listing, but a quick check with local historians indicated there was no official historical designation. There was also the issue of the age of the building complex since no architectural survey had been done, as well as the question of where the pottery ended and the paper mill began.

I decided at this point to become more involved. I called William Kraus, vice president of the Norwalk Preservation Trust, and explained who I was, what my interest was, and that I had been doing considerable research on the property and its history. Bill asked me to assemble packages of information—dated maps, surveys, historical research—that he could present at a meeting with the state archaeologist, Nick Bellantoni. I also met with Tod Bryant, president of Norwalk Preservation Trust, and voiced my concerns about delays. Tod assured me that everything was moving as quickly as possible and that if I supplied him with information packets, he would see to it that they reached the proper people.

And suddenly everything did start moving quickly. Town officials were supplied with information that previously had not been available, the developer was presented with requests and proposals, engineers were making reports, and archaeologists were questioned about surveys. The mayor requested that all involved parties try to resolve issues equitably and suggested that a delay of any permanent action might be helpful. For a short time there was hope that this historic building could be preserved, or at least adapted for reuse. And it was gratifying to see everyone working in a spirit of cooperation.

Just as suddenly, however, the upward spiral began to reverse itself. Two engineering firms that had examined the building declared it unsafe and unsalvageable. As a result, the town closed the adjacent street (for pedestrian safety), condemned the building, and ordered the demolition of the structure. The developer agreed that Tod Bryant, because of his skill as a photographer and his role as president of the Norwalk Preservation Trust, would be allowed to photograph all phases of the demolition for the historical record. I introduced Tod to an archaeologist teaching at Norwalk Community College in the hope that at least an archaeological survey could be made during each stage of the demolition. I was not very hopeful that the building could be salvaged, but thought some concessions might be granted to preserve a little of its history.

Connecticut law regarding historic structures resides to no small degree with individual municipalities. For a city within the state to have historical designations, it must first empower a “historical commission,” which derives its power from the state. The commission determines which buildings and sites within the municipality are of historical importance. The approval of a designated site gives greater leverage to the mandate of an archaeological survey. Typically, contract archaeologists are not retained unless state or federal funding is involved and the specifications of the project call for a survey to be made. By the same token, if a site or building has no such designation and is in private hands, there is little to require developers to opt for conservation.

And so, in late August, a huge excavator and large front-end loader were brought to the site and demolition began. At first the long addition built for the pulp and paper mill was brought down (fig. 7). The operators picked at the building with machinery separating the different types of materials as they worked. Each night there were separate piles of brick, metal, wood, and miscellaneous debris, which were hauled out by trucks the next day (figs. 8-14). The work drew a small crowd of curious onlookers and reporters from the local papers. By the end of the first week the entire south end of the building had been dismantled and removed from the premises. A short delay followed, raising our hopes that someone was still maneuvering to salvage something of the old pottery. It was merely a brief respite, however, as the wrecking crew shortly set to work pulling down, layer by layer, the remaining sections of the skeletal infrastructure. All that remains is a surrounding chain-link fence for public safety (fig. 15).

As the dust settles from the destruction of the Smith pottery building, future research will focus on the large quantity of earthenware and stoneware sherds collected from the site. At least twelve garbage cans full of sherds have been donated to the Norwalk Museum, where they await analysis and publication. The insights gained from the study of these sherds may help provide firm attributions for antique specimens that appear in the marketplace or that currently reside in public and private collections. One example is the recently acquired “Norwalk Plate,” dated February 13, 1854, which has been attributed to the Smith pottery (fig. 16). My research and subsequent digs at other Norwalk sites call this attribution into question. Asa Smith, primarily a stoneware potter, has been credited with the redware work, yet I did not find a single sherd of scripted redware among the thousands recovered at the Smith pottery site. Two other sites in South Norwalk have yielded scripted examples, however, and research into this issue is ongoing. While the loss of the Smith pottery buildings is a blow for the historic preservation community, we can remain optimistic that information will continue to surface from below the ground—preferably through excavation but even through demolition—and help fill gaps in the known history of Connecticut’s ceramic history.

The history of ownership and the value of preserving such buildings is outlined in a letter to the editor published in the local Norwalk paper The Hour on July 23, 1998.

Connecticut Historical Collections, Containing a General Collection of Interesting Facts, Traditions, Bibliographical Sketches, Anecdotes, &c. Relating to the History and Antiquities of Every Town in Connecticut with Geographical Descriptions by John Warner Barber. 1836. Published in an Improved Edition, with Additional Engravings in New Haven in 1849 (1836, 1849; Storrs, Conn.: Bibliopola Press, 1999).

Connecticut Business Directory: Containing the Name, Location and Business of the Principal Manufacturing Establishments, Mercantile Firms, &c., for the Year 1851 (New Haven, Conn.: J. H. Benham, 1851), p. 249.