Presentation basin, southeastern Pennsylvania (likely Philadelphia), ca. 1730–1760. Trailed slipware. D. 14". (Courtesy, The National Society of The Colonial Dames of America in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania at Stenton; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This reconstructed bowl was recovered in 1982 at Stenton, James Logan’s plantation (see fig. 2), by archaeologist Barbara Liggett.

Stenton, James Logan’s country house and plantation, built 1723–1730. (Photo, The National Society of The Colonial Dames of America in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania at Stenton.) The basin illustrated in fig. 1 was found in a cistern behind the home.

Detail of the basin illustrated in fig. 1. This slip-decorated Native American figure, with painted torso and tall rifle, represents Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow, chief of the Maguas.

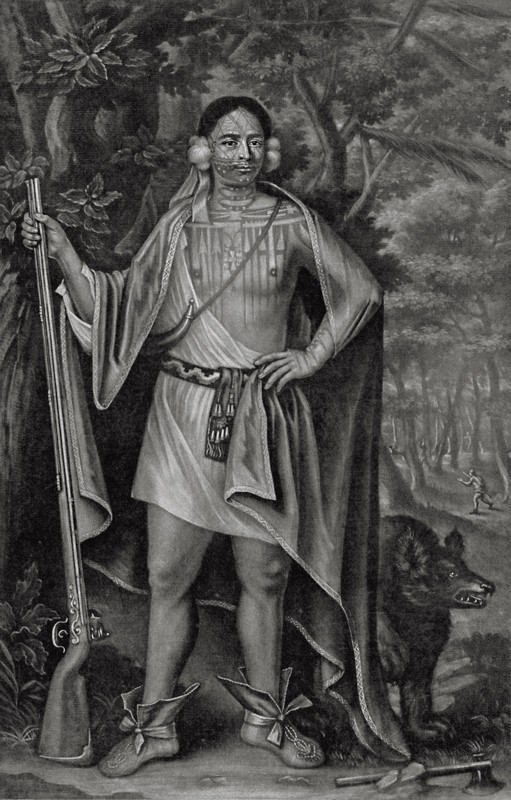

John Simon, Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow, King of the Maguas, 1710. Mezzotint. 16 5/16 x 10 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, museum purchase.) This mezzotint is one of a set of four, after full-length oil portraits commissioned of John Verelst by Queen Anne.

The murals on the stair landing in Archibald Macpheadris’s house (now known as the Warner House), ca. 1718–1720. (Courtesy, Warner House Association; photo, Richard Haynes.) Possibly the work of Nehemiah Partridge, the murals served as a reminder of the Iroquois promise in 1710 to be faithful British allies.

Basin, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, early nineteenth century. Redware. H. 3 1/4", D. 10". Inscribed on exterior base: “Jos Rupp Jr / Ephrata / Lanc Co / Penn.” (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Orrin W. June.) The inscription alternatively suggests that the Stenton bowl could have been made on the Pennsylvania frontier.

This reassembled redware bowl might have been made by a colonial potter in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, sometime between 1730 and 1750 (fig. 1). Its colorful fragments were recovered during a 1982 excavation at Stenton (fig. 2), the nearby 511-acre country house of James Logan (1674–1751), a Scots-Irish–born Quaker from Bristol, England, who was William Penn’s agent and Proprietary Secretary, as well as the architect of Pennsylvania’s “Indian Policy” in the first half of the eighteenth century.

The bowl’s archaeological context was a probable cistern situated behind the original kitchen/washhouse complex to the rear of the house, all contemporary to the house’s original construction, about 1730.[1] Other ceramics found on the site, dating from circa 1740–1765, include Chinese porcelain and a variety of refined and coarse earthenware. A layer of intact mid-eighteenth-century glass bottles topped this rich deposit. Archaeologist Barbara Liggett commented that the Stenton assemblage was the “densest single collection of mid-eighteenth-century artifacts” she had ever seen in her long career.[2]

Liggett described the Stenton vessel as a “locally-made, slip-decorated earthenware bowl, with Native American Indian, unique, indicating Logan’s formal association with the Indians.”[3] Decorated in the English tradition of presentation pieces, it resembles seventeenth-century Staffordshire slipware that depicts a cast of characters, ranging from ruling monarchs to Adam and Eve. The bowl also resembles a large group of surviving late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century American slip-decorated presentation pieces depicting soldiers and horsemen traditionally associated with Pennsylvania German production and consumption. The lack of wear to the glazed interior surface combined with the pictorial nature suggest that the Stenton bowl was created for show rather than for everyday use.

Although the bowl’s form looks like a simple pewter basin, its unusual interior motif—a Native American, drawn in white slip, who stands alongside his long-barreled rifle—elevates its stature.[4] It is possibly the only known piece of redware made in America prior to 1750 that is decorated with an image of a Native American. The figure has been identified as Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow, chief of the Maguas, a group of Mohawk Indians (fig. 3). (The Mohawk were one of the Five—later Six—Nations of the Iroquois League.) Because of this depiction and where it was found, we can formulate a historical context for the bowl by examining the lives of Logan and Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow, who, despite their diverse cultures, are somehow connected.

Accompanied by three other Iroquois representatives, Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow—also known by his Anglican name, Brant—set sail for England in February 1710. Arriving in London, they hoped to find and enlist missionaries to instruct their people in Christian doctrine, as well as to receive military aid for their defense against the French. For the English, however, the visit was entirely a display of Iroquois power as defined by British imperialism.[5] The English, who described the Iroquois as “kings,” hoped the visit would cement the loyalty of the Five Nations to the British Crown, since the Iroquois were continuously courted by the French, rivals of the British for colonial territory and trade. Toward this end, the weapons and trade goods proffered by the British nation helped ensure the Iroquois’ ability to police and influence other Native American groups.

In fact, the crudely slipped figure was taken from a set of four mezzotints of the four Native American “kings” engraved by John Simon of London in 1710, after full-length oil portraits by John Verelst that had been commissioned by Queen Anne (fig. 4).[6] These portraits are among a small number of European-style paintings of Native Americans. While the full-length depictions show the “kings” in their Native American clothing, typical European portrait conventions were used to convey power: legs wide in an authoritative stance, weapons and totems at the ready. Fundamentally respectful, the images convey that the four Iroquois from America were trusted leaders and allies—just as the English calculated them to be.

James Logan, too, set sail for England in 1710, reaching London at the end of March. His mission was to sort out some of William Penn’s political and financial difficulties related to Pennsylvania. However, as Penn’s land agent Logan would have been interested in the implications of the visit by the Iroquois representatives.[7] In an earlier letter to Penn, he had written that “the only way to procure peace to the English colonies here from the attempts of the intriguing enemy [France], seems to be a strong attack at sea; for if we loose [sic] the Iroquois, we are gone by land.”[8] Logan’s Indian policy was essentially to use the Iroquois to police the Pennsylvania tribes and the Delaware and Susquehanna River Valley Indians. Further, the Iroquois Nations of New York were a buffer from the French in Canada to the north. Since pacifist Pennsylvania with its Quaker roots had no militia, it was necessary to use the Native Americans as their land defense from French attack.[9] Thus, the political result of the Iroquois visit and their reception by Queen Anne was important to James Logan, regardless of whether he was one of the Americans who accompanied the “royal four” on their tour abroad.

In 1718 the sets of the four engravings by Simon took an international turn when they arrived in Albany from England with the Reverend William Andrews from the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel missionary to the Iroquois. Andrews brought 51 sets (each set comprised 4 prints; 12 of the 204 prints were framed).[10] Of the three sets in frames, we know that one set went to New York and one to Boston, to be placed in Council chambers. Among the unframed sets, eight went to New York, four to New Jersey, eight to Boston, four to New Hampshire, four to Rhode Island, and four to Pennsylvania, as well as one to each of the Five Nations and the River Indians, one to each of the four Natives who traveled to London, and one each to the governors of Maryland and Virginia to be hung in Council chambers.[11] With four sets having been sent to Pennsylvania, it would be surprising if Logan, with his ties to the Natives and Indian policy as well as his position in Pennsylvania government, did not acquire a set of his own. For the British, the images of the “Four Kings” came to represent “the expanding horizons of empire . . . and symbols of the reach and scope of English power.”[12] In the American colonies they may have been used by wealthy or politically powerful individuals as visual reinforcers of friendship and alliance with Native Americans, as in the case of the magnificent murals displayed in the New Hampshire home, built 1716–1718, of merchant and shipowner Captain Archibald Macpheadris (fig. 5).

Moving ahead some two decades to Pennsylvania, the Stenton bowl may have come into play during the treaty negotiations with the Iroquois at Philadelphia in the 1730s and 1740s. In 1730 James Logan, having amassed great wealth in the fur trade, as part owner of an iron furnace, and through land ownership, removed from Philadelphia to Stenton, his country house seat nearly five miles north and west of the city, choosing a site between two major roads in and out of Philadelphia: the York Road (to New York) and the Great Road (or Germantown Road) west to the Pennsylvania frontier, an important route for the fur trade. Essentially, Logan situated Stenton on a site that allowed his property to function as a kind of threshold to Philadelphia, a convenient stopping point for both the transmission of goods and news and a stopping place for Native Americans.

Stenton’s role as a kind of gateway, however, contributes to an uncertain location for the manufacture of the bowl. Many of the goods in Stenton’s archaeological collection are of quality manufacture, such as the fine porcelains imported from China to England and then Philadelphia. In terms of Stenton’s style and the furnishings owned by Logan that survived, this gentrified English merchant took his cues from across the Atlantic. The redware basin, perhaps made in Philadelphia where Logan obtained many of his goods, could also have been made outside the capital city.

For example, the redware bowl is similar to a somewhat smaller form in the Winterthur collection (fig. 6). The catalog information for the Winterthur piece dates the vessel to the early nineteenth century and attributes it to Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. “Jos Rupp Jr / Ephrata / Lanc Co / Penn.” is inscribed on its bottom in pencil. The Ephrata connection suggests a possibility that James Logan acquired his bowl through Conrad Weiser (1696–1760), his interpreter and go-between to the Native Americans and onetime inhabitant of the small Pennsylvania borough.[13]

For Native Americans and colonials who neither spoke each other’s language nor fully understood each other’s customs, the exchange of gifts was paramount to establishing and maintaining a relationship. A Native leader maintained his status not by the accumulation and display of goods, but by giving gifts to as many of his people as possible. Further, Iroquois culture and communication involved the use of artistic imagery and metaphors to convey ideas and concepts: clouds depicted “trouble or threats that overshadowed relationships”; a rope or chain represented an alliance or relationship; a path or road symbolized communication; and a road “full of brambles or fallen logs” indicated poor communication and disputes.[14]

In an attempt to use the Indians’ symbolic imagery, perhaps the Stenton redware bowl was an extension of this tradition in clay, commissioned by Logan for use in a Condolence or Wood’s Edge Ceremony that may have taken place at Stenton prior to or following one of the treaties at Philadelphia.[15] The use of the image in such a way would have visually and powerfully recalled the London alliance promised in 1710. One ritual employed prior to treaty negotiations was the metaphoric washing away of all impediments to communication. Perhaps the bowl, recalling the goodwill and solidarity of the Iroquois-English affiliation, was used as a basin for a literal and symbolic cleansing prior to talk between the colonists and Native Americans at Stenton. Or the basin may simply have represented an attempt to touch base with Native American neighbors, the offering of a commemorative gift that would further nourish an important friendship. Whatever the precise meaning or origin, this one-of-a-kind redware bowl incorporates the cultural customs and communication traditions of both the Native Iroquois and the colonial settlers into a single colonial North American artifact.

Laura C. Keim, Curator, Stenton; laura.keim@stenton.org

David G. Orr, Assistant Professor, Temple University; daveorr@temple.edu

The best published summary of this admittedly enigmatic context can be found in John L. Cotter et al., The Buried Past: An Archaeological History of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992), pp. 336–37. Note that the site plan in The Buried Past shows the vault in question as feature 121 and confusingly labels a nearby “privy” as feature 13. All of Liggett’s memos refer to the provenience as feature 14; although she alternately calls it both “vault” and “privy.” Deborah L. Miller, “Just Imported from London: The Archeology and Material Culture of Stenton’s Feature 14” (master’s thesis, Pennsylvania State University, 2006), pp. 19–21, makes a strong case that the feature was a retired cistern.

Memorandum of a meeting with Barbara Liggett, unpublished typed manuscript, November 21, 1989, p. 4 (Stenton archives).

Ibid. The second page of this memo lists some of the more outstanding finds from the dig, including the bowl. Liggett believed that the assemblage predated 1755. That the bowl depicted a Native American had been forgotten until Stenton undertook its Interpretive Plan Project in 2003, when consultant Scott Stephenson alerted us to the importance of the image.

According to Dr. Patricia Gibble, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Elizabethtown College, Elizabethtown, Pennsylvania, this form is described in period sources as a bowl, a patty or pasty pan, or a milk pan.

These Natives were young and uninfluential in Iroquoia; in truth, they did not even represent the Five Nations. See Eric Hinderaker, “The ‘Four Indian Kings’ and the Imaginative Construction of the First British Empire,” William and Mary Quarterly 53, no. 3 (July 1996): 491.

Simon, the engraver chosen by Verelst, was highly skilled and able to produce a set of images that faithfully follow the complex original paintings.

Frederick B. Tolles, James Logan and the Culture of Provincial America (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1957), pp. 83–84.

James Logan to William Penn, Philadelphia, March 2, 1702, in The Penn and Logan Correspondence, edited by Edward Armstrong, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott and Company for The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1870), 1: 88. See also Tolles, James Logan, p. 36.

Logan, though a Quaker, was not a pacifist. He believed that Pennsylvania needed a militia for defense. He was reprimanded by the Meeting for having sailed out to an island in the Delaware River with armed deputies to remove a squatter in 1702. Tolles, James Logan, p. 28.

Hinderaker, “The ‘Four Indian Kings,’” p. 509.

John G. Garratt, The Four Indian Kings ([Ottawa]: Public Archives of Canada, 1985), p. 14.

Hinderaker, “The ‘Four Indian Kings,’” p. 488.

Weiser attended the 1736 and 1742 Councils in Philadelphia, which involved time spent “in the bushes” at Stenton. “In the bushes” was an Indian phrase referring to pre- and post-formal negotiations removed from the Council Fire. Occasionally these were “Wood’s Edge” ceremonies that usually took place prior to the primary Council in a clearing—hence the term. Wood’s Edge gatherings—a variation on the Condolence Ceremony, which set aside time to grieve for those who had died since the previous meeting—also allowed participants to prepare for the journey to the Council. In June 1742 Logan fed and sheltered on his property a Six Nations delegation of 188 men, women, and children, as well as more than 40 Indians from Pennsylvania. The Indians were disappointed to find Logan retired from public life and “hid in the bushes.” They convinced Logan to travel with them to Philadelphia, but their description of Logan as “hid in the bushes” indicates that they conducted pre-Council negotiations at Stenton before going to Philadelphia in July. Tolles, James Logan, pp. 181–82; Francis Jennings, ed., The History and Culture of Iroquois Diplomacy: An Interdisciplinary Guide to the Treaties of the Six Nations and Their League (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1985), p. 116.

Jennings, History and Culture of Iroquois Diplomacy, pp. 117, 121.

An early secondary source tells us that Natives encamped at Stenton on June 6, 1749: “There were Indians about the city at the same time, making together probably four to five hundred Indians at one time. The same Indians remained several days at Logan’s place, in his beech woods.” John H. Watson, Annals of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania in the Olden Time, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: J. M. Stoddart and Co., 1857), 2: 163.