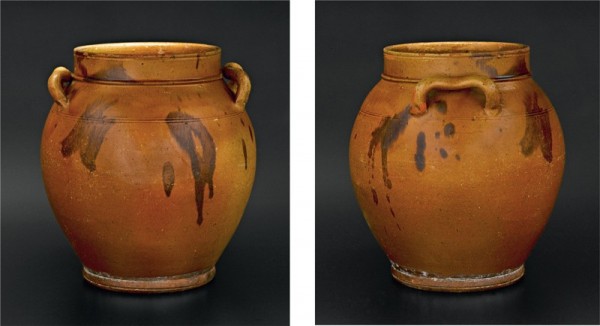

Jar, probably Greenport Pottery, New York, ca. 1819. Lead-glazed earthenware daubed with manganese oxide. H. 9". (All photos, Gavin Ashworth.) This jar was found in a home within one mile of the former Greenport Pottery, located on Sterling Street in Greenport, New York, on Long Island’s North Fork.

Detail of the handle attachment for the jar illustrated in fig. 1. Note how the pulled handle comes in contact with the neck of the jar.

Jar fragments, probably originating from a jar identical to the one illustrated in fig. 1. These sherds were found among large amounts of redware fragments located under an eighteenth-century home located directly adjacent to the Greenport Pottery site.

The recent discovery of an unusual pot in a home on eastern Long Island may shed new light on the evolution of redware pot designs in the region. Does this piece represent a heretofore undocumented, short-lived phase in early redware production, or is it simply a local potter’s attempt to compete with the stoneware vessels of the day? If this pot does represent a common early form, why have no other examples come to light? Could it be that the fragile nature of this vessel made it susceptible to breakage, forcing a rapid transition to a sturdier design?

Although ovoid redware pots are very common in the antique market and were apparently made in large numbers during the first half of the nineteenth century by potters in Huntington, New York, Norwalk, Connecticut, and New Jersey, this pot (fig. 1) appears to be distinct in several ways and may be earlier than many of those previously seen.[1] It differs from the southern New England/Long Island redware pots so typical of the mid-nineteenth century in that it has a deep, thin-walled vertical collar and open handles set off from the body, similar to a typical early-nineteenth-century stoneware vessel from Manhattan. The only difference between this piece and the stoneware form is that the handles on this pot come in contact with the body (fig. 2), a feature probably necessitated by the weakness of earthenware. The common redware form has a thick-walled vertical or flaring neck and lug handles that are tight to the body.[2]

The story behind how I acquired the pot is one of missed opportunities, lessons learned, and a bit of luck. It came to market in 2001 when an antique dealer acquired it from a home near the village of Greenport, New York, and sold it through an online auction. At the time of that sale I had admired the piece, noted the local provenance, balked at the current bid, and filed a copy of the page away in my notebook. Several years later I was leafing through my notebook and decided to try and track down the pot. I had never viewed the final auction page and therefore did not know who won the bid. I contacted the seller, who informed me that he no longer had a record of the transaction. With auction forensics I eventually narrowed the winner down to a likely candidate and sent him a brief note. To my delight, I had found the right person, he still had the pot, and, in another stroke of luck, had it up for sale! Although, of course, the price was higher than the original auction, I could not complain, because at least the pot was coming home to Long Island. Lessons learned: keep detailed records; and, if you really want a piece, buy it the first time you see it!

The question of attribution for this pot is not as easy to answer as I would like, although there are several clues that tend to point to one particular maker. It is my contention that this pot was likely made during the early days of the Hempstead kiln in Greenport, a redware pottery started by Austin Hempstead and Samuel Osborn in 1819.[3] A North Fork, Long Island, provenance would appear to place this piece squarely within the short, wagon-cart distribution that characterized the early days of that pottery. Clouding this picture, however, is the fact that I have found discard sherds under local homes that prove the market was filled with wares from the potteries of Huntington, New York, and, in particular, Norwalk, Connecticut. Therefore, it is not out of the question to think that a piece from one of these major potting centers could be found so near the Greenport pottery site (about one mile). The color of the pot, a mustard brown, is also in keeping with how Greenport pieces were described by early collectors, but, as most know, attribution based on glaze color is tenuous at best.[4]

Further evidence for local manufacture was uncovered in the summer of 2006. I had been given permission to investigate the crawl space under an eighteenth-century home located on the shore of Sterling Harbor in Greenport, directly adjacent to the Hempstead kiln. The house was to be lifted to make way for a full basement, and I was able to perform a little salvage archaeology before the dig. Over several hours of crawling under this home, I gathered a large number of shell-edge, banded, and luster fragments along with quantities of redware. I suspect that some of the redware originated from the nearby kiln based on the proximity of the home as well as the number of misfired and damaged “seconds” in the assemblage. Among these pieces I found three sherds (fig. 3)—two base sherds and a fragment of a collar—that match the intact pot in body thickness, glaze color (inside and out), decoration, and neck and foot detail. Unfortunately, there were no handle fragments to give a positive match.

It must be said that this vessel does bear a strong resemblance to a large stoneware vessel made at the Lewis and Gardiner pottery (1827–1829) located in Huntington.[5] Although there is no indication in wasters found in Huntington of such a form being produced in redware, I have collected green-flecked, slip-decorated wasters at the Huntington site that would appear to indicate that redware was produced during the first quarter of the nineteenth century there. However, if this pot originated in Huntington I would expect—given the size and production of that kiln—to find more examples in local collections.[6]

One might ask why such a fragile pot was ever made. More durable stoneware alternatives were readily available from other sources. Indeed, I have found in the area several J. Remmey III pot fragments with incised blue-cobalt decorations of various sizes—I even purchased an intact albeit completely misshapen one, a small pot out of a home in Greenport. Stoneware pots and jugs marked “W. STATES”—manufactured in Stonington, Connecticut, directly across Long Island Sound—have also been found under local homes. From this evidence it is clear that early stoneware potters were filling a niche that was not or could not be filled by local potters. Could it be that Hempstead, seeing a ready market for this type of vessel, set out to capture a portion of this market? Did its lower cost make a redware pot competitive in the market despite its lower durability? Or was there some domestic need for redware in the early-nineteenth-century kitchen that could not be filled by stoneware?

Regardless of the forces that led to the making of this pot, I believe that it represents an early design or even a precursor to the typical southern New England pots that are seen more commonly today. I believe that this is one of the first examples of a horizontally mounted handle and that over time the handles evolved or devolved (depending on your perspective) into the eyebrow handles seen on many extant pots. Several jars illustrated in Anthony Butera Jr.’s article “Informed Conjecture: Collecting Long Island Redware,” previously published in this journal, provide a possible evolution of handle design from the open handles of this jar (see fig. 1) to the stylized eyebrows found on other pots.[7]

As with most studies of redware, there are more questions raised than answers given. Nevertheless, a uniquely elegant and extremely fragile piece of redware has survived nearly two hundred years to be enjoyed today. I hope that my studies of the Greenport pottery will shed sufficient light on this and other pieces to place this early Long Island factory among the other significant redware centers of the nineteenth century.

Christopher H. Pickerell, Habitat Restoration Specialist,

Cornell University; cp26@cornell.edu

Lura Woodside Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1950), p. 239.

Anthony W. Butera Jr., “Informed Conjecture: Collecting Long Island Redware,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2003), p. 218, figs. 8–10.

Cynthia Arps Corbett, Useful Art: Long Island Pottery (Setauket, N.Y.: Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities, 1985), pp. 68–79.

Preston R. Bassett, “The Local Potters of Long Island,” Long Island Courant 1, no. 1 (March 1965): 1–14. The author states, “The Greenport redware, however, ran to rich dark browns rather than the reds of Huntington ware.” Ibid., p. 12.

William C. Ketchum Jr., Potters and Potteries of New York State, 1650–1900 (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1987), p. 90.

Corbett, Useful Art, pp. 20–47.

Butera, “Informed Conjecture,” pp. 218–19. I believe that the handle type illustrated on page 218, figs. 8 and 9, represents the next stage in handle design after the open handle design seen on my pot. Figure 10 on the same page appears to show a pulled handle that has the same basic circular cross-section but with additional clay added, probably to add strength. Figure 11 (p. 219) illustrates a very stylized handle with no hint of the circular cross-section seen in the other examples. This design may represent the final stage in the evolution of handle design for these jars.