Teapot, possibly Huntington Pottery, Huntington, New York, ca. 1820–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 1/4", D. of base 4". (Courtesy, Greenlawn-Centerport Historical Association; all photos, Robert S. Kissam.) The major difference between this example, found at the Suydam Homestead site, and the Thomas Crafts teapot illustrated in figs. 5 and 6 is the flat bottom.

Base of the teapot illustrated in fig. 1.

Teapot, possibly Huntington Pottery, Huntington, New York, ca. 1820–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 1/2", D. of base 3 1/2". (Courtesy, Greenlawn-Centerport Historical Association.) Although somewhat similar in appearance to the Crafts pot, the manganese-enriched lead glaze on the Suydam pots has a slightly glossier metallic shine.

Base of the teapot illustrated in fig. 3.

Teapot, Thomas Crafts, Whately, Massachusetts, ca. 1820–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 7". (Collection of Anthony W. Butera Jr.)

Base of the teapot illustrated in fig. 5. Note the cutout bottom.

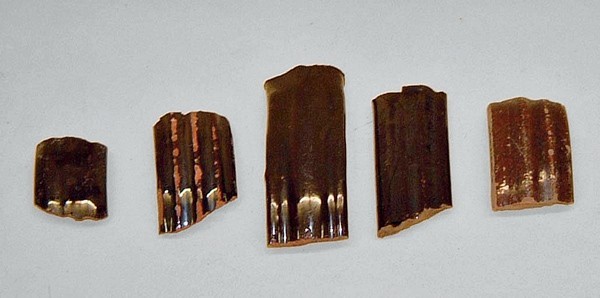

Extruded handle sherds, possibly Huntington Pottery, Huntington, New York, ca. 1820–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. L. of longest 2 1/2". (Courtesy, Greenlawn-Centerport Historical Association.) These sherds were found at the Suydam Homestead site.

Teapot base, possibly Huntington, New York, ca. 1820–1840, with a setting ring from the Huntington Pottery. Lead-glazed earthenware. Base D. 3 3/4". The discovery of a setting ring for firing flat-bottomed pots at the Huntington Pottery site suggests the source of the Suydam teapots. (Courtesy, Greenlawn-Centerport Historical Association.)

In the early 1990s the Greenlawn-Centerport Historical Society began the restoration of its recently acquired Suydam Homestead in Centerport, Long Island, New York, approximately three miles east of the Huntington Pottery site. The house was built about 1730 and added onto over the years. In the early nineteenth century, a building that dated from the eighteenth century was moved and attached to the west side of the house. It was in that part of the house, while taking up a floor that had been laid down in the 1930s, that an enormous amount of local earthenware sherds was discovered, along with a large quantity of English hand-painted creamware, pearlware, and other artifacts. Included in this find were sherds of at least four different earthenware teapots, two of which are illustrated in figures 1 through 4.

On first examination these teapot fragments are similar to extant examples of the Thomas Crafts teapots of Whately, Massachusetts (figs. 5, 6). There are differences, however, making an attribution to Crafts tentative. The Crafts teapots have been cut out on the bottom to form a rudimentary foot. Those from the Suydam Homestead have a completely flat bottom, a potting technique traditionally thought of as American. The Suydam Homestead teapots have a more flattened finial, the extruded handles have more fluting (fig. 7), and the glaze has more of a metallic shine than the Crafts pots. With these differences in mind, it should be safe to assume that the teapots were made elsewhere.

Since most of the red earthenware sherds found at the site have been attributed to the Huntington Pottery, were these teapots also made at Huntington? We do know that teapots were manufactured in America before 1840.[1] Since the Huntington Pottery is so close to the Suydam Homestead and has a long history of operation in the area, the possibility of local manufacture is feasible.[2] The discovery of a setting ring at the Huntington Pottery site makes this argument even more appealing (fig. 8). Recently, more teapot fragments have been found at the Daniel W. Kissam House in Huntington.[3]

The red earthenware sherds found at the Suydam Homestead were not the only ceramic material excavated, however. The house’s long history produced the typical ceramic history, as mentioned earlier. The teapots could have come from the Philadelphia area or, perhaps, from England, since sherds characteristic from those places were found at the site. We also cannot rule out the possibility that the teapots were made in another area in America.

The purported relationship between the Huntington Pottery and the Suydam family should be noted here. Although no written history has been found, local tradition maintains that the Suydam family and the Huntington Pottery shared a business relationship. It has long been believed that the painting by Edward Lang of the Brown Brothers pottery depicts the Mary Emma, a schooner owned and built by the Suydams and named after Mary Emma Suydam.[4] It is possible that the Suydams’ shipping business brought pottery forms and decorations to the area, and that the Huntington Pottery adopted these popular styles.

The Suydam Homestead sherd collection illustrates the importance of proper archaeological procedures. In the past, much information was lost when hoards of sherds similar to what was found here were improperly handled. The Suydam Homestead archaeological collection is an excellent resource for historians and ceramic enthusiasts and will continue to yield valuable information.

Anthony W. Butera Jr., Collector of Long Island Red Earthenware;

erawder@optonline.net

Robert S. Kissam, Trustee, Huntington Historical Society;

kissam@gmail.com

Reginald H. Metcalf, Collector and Historian; Lifelong Member,

Huntington Historical Society; rexmet@optonline.net

Lura Watkins explains, “Although redware teapots were not among the regular articles listed in the account books of early potters, they had in fact been made for decades and even by some of the eighteenth-century men.” Lura Woodside Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1950), p. 104.

Watkins’s discovery of John Parker’s daybook proves “that the early redware maker was not limited in his output to coarse jugs, pots, and pans for the kitchen, but was accustomed to furnish all the smaller and more delicate articles that were for use on the table. . . . Only the extreme fragility of the ware has prevented our having examples of these once familiar objects.” Ibid., p. 30.

The Daniel W. Kissam House, built in 1795, is owned by the Huntington Historical Society and is located at 434 Park Avenue, Huntington, New York. During the recent repainting of the front of the building, a few of the original shingles had to be removed, uncovering three teapot sherds, an inkwell (complete but broken in half), two-thirds of a porringer, and a fragment of a slip-decorated dish.

Cynthia Arps Corbett, Useful Art: Long Island Pottery (Setauket, N.Y.: Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities, 1985), cover ill.