Workshop guests may stay for free in a circa 1793 tavern reconstructed at Eastfield Village. (Unless otherwise noted, all photos by Merry A. Outlaw.)

Reproduction pottery may be purchased at the circa 1811 Elias Brown General Store.

A misty morning walk into quaint Eastfield Village.

Exterior of the 1836 First Universalist Church, Eastfield Village, East Nassau, New York.

Inside the church, tables are set with pots and equipment. James Mattozzi, left, and Jonathan Rickard, right, discuss Rickard’s dipped-ware collection.

Sherds from the Wood and Caldwell waster tip, Burslem, 1795–1805.

These hand-painted polychrome pearlware vessels are from a circa 1797 pottery dump in Albany, New York, and match examples from the Wood and Caldwell tip.

Jonathan Rickard brought antiques for comparison to the Wood and Caldwell sherds.

Reconstructed vessels from the 1829–1837 Lewis Pottery in Louisville, Kentucky.

Irish potter Nicholas Mosse demonstrating transfer-printing techniques. (Photos, James Mattozzi.)

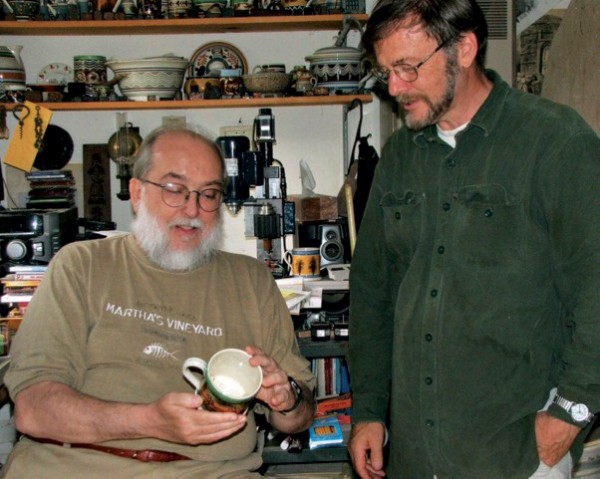

Jonathan Rickard, left, examines an antique dipped-ware tankard from the studio collection of Don Carpentier, right.

Brilliant, determined, and insightful are a few of the adjectives that describe Don Carpentier, who in 1971 began single-handedly reassembling a circa 1830 blacksmith’s shop in East Nassau, New York, in order to learn building skills no longer utilized. The reconstruction was the first in a series of twenty-eight, which would become known as Eastfield Village, a circa 1820–1840 American town.

In the process of building and furnishing Eastfield, Don became a self-taught tinsmith, woodworker, blacksmith, and potter, and over the years he has shared his knowledge and skills in annual workshops on these period trades. Craftsmen, scholars, antique dealers, and collectors come together in these seminars as teachers and students to learn more about the past. To better understand early-nineteenth-century lifeways, participants are offered gratis housing in a late-eighteenth-century tavern with no electricity or running water (fig. 1). Guests cook their meals in a kitchen fireplace, sleep on rope beds in candlelit rooms, use a nearby privy, bathe in a lake behind the tavern, and shop for reproduction ceramics in the restored general store next door (fig. 2).[1]

For years I had read about Don in publications such as Country Life, Colonial Homes, Maine Antiques Digest, and Early American Life. I admired and purchased many of his late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century English pottery reproductions in Yorktown and Williamsburg, Virginia. Ever since 1996, when he and Jonathan Rickard established the three-day ceramic workshops, popularly known as “Dish Camp,” I wanted to go. Thus, when the opportunity to attend the June 2006 conference was offered, I quickly packed my bags! Entitled “British Ceramics: A Newly Discovered Potter’s Tip in Burslem, 1795–1805,” the focus was on a large ceramic waste tip of the 1790–1819 Wood and Caldwell manufactory in Burslem. Don salvaged it in February 2006. The schedule of well-known scholars, archaeologists, and potters included Louise Richardson, Jonathan Rickard, Charles Fisher, Diana Stradling, Robert Genheimer, Nicholas Mosse, Denise Carpentier, and Susan Myers.

Traveling with friends to Eastfield for the first time, the progressively rural countryside foretold what was to come. On arriving, we parked a short distance from the village and followed a dirt path through a meadow until the intimate setting of old buildings situated around a village green came into view (fig. 3) and we began our step back in time—with a few modern conveniences.

The conference was held in the reconstructed 1836 First Universalist Church (fig. 4). The church interior was furnished not only with the expected pews and lighting but also with tables, chairs, and fans, plus a large screen, a projector, a computer for PowerPoint presentations, and a network of power cords for the electric equipment in this unwired edifice (fig. 5). Friendly family dogs wandered among us, setting the stage for a homey and relaxing atmosphere.

Tables had orderly displays of ceramic sherds salvaged by Don from the threatened archaeological Wood and Caldwell waster tip (fig. 6). Because of space limitations in the church, the display was but a sample of the total assemblage, yet it included pearlware, redware, and stoneware in a variety of vessel forms. Many decorative techniques were recorded on the sherds: dipped, inlaid, engine-turned, encrusted, molded, sprig-molded, hand-painted, and transfer-printed.

Opening the workshop, Don presented a detailed discussion of the tip site, the wares recovered, and reasons for the Wood and Caldwell attribution. From Charles Fisher we learned of close Wood and Caldwell parallels to pottery broken in shipment and dumped by John Fonda Jr. (also known as John Fondey Jr.), a ceramic merchant in Albany, New York, in a deposit that was sealed by fire in 1797 (fig. 7).[2] Documentary and material evidence for Wood and Caldwell in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, was presented by Louise Richardson.[3] Complementing Don’s fragments, Jonathan Rickard shared intact antique vessels related to Wood and Caldwell, and presented a brief history of the Wood family (fig. 8).[4]

Important information concerning an American archaeological ceramic assemblage with English ties was presented by Diana Stradling and Robert Genheimer.[5] From the circa 1829–1837 Lewis Pottery in Louisville, Kentucky, examples of the banded yellow ware sanitary and kitchen objects also were available for examination (fig. 9). The shapes and decoration were clearly derived from English prototypes.

Nicholas Mosse of the Nicholas Mosse Pottery in Kilkenny, Ireland, demonstrated transfer-printing and sponged decoration techniques (fig. 10).[6] The patterns on the Wood and Caldwell sherds were compared to antiques and archaeological examples by Denise Carpentier of Eastfield, who also showed us how the hand-painted motifs were done.[7] The final presentation was by Susan Myers, who shared interesting new research on how nineteenth-century potters responded to American drinking habits and the temperance movement.[8]

Participants in the Ceramics Workshops are encouraged to bring antique ceramics or sherds to the workshop in order to exchange ideas. Thus, collector Anthony Butera Jr.[9] came with early-nineteenth-century redware vessels made in Long Island, New York. Jim Mattozzi shared a delicate circa 1765–1770 English porcelain sweetmeat stand with underglaze-blue decoration.[10] And Don opened his pottery studio to show his own antique dipped-ware collection and his stunningly precise reproductions (fig. 11).

The collegial interaction between lecturers and students, the availability of sherds and vessels for study, and demonstrations of pottery-making techniques make this program invaluable for learning about ceramics in historic American contexts. Because the seminar is limited to about thirty-five people, enroll early to take this step into the past, and check the Eastfield Village website often![11]

Merry Abbitt Outlaw, New Discoveries Editor, Ceramics in America;

xkv8rs@aol.com

Not one to rough it, I stayed with several conference attendees in one of many nearby bed and breakfasts. We bought takeout sandwiches for lunch on the way into Eastfield and ate dinners in one of several fine restaurants in the area.

Charles Fisher was a published author and widely respected in the New York history and American historical archaeology communities. Before his untimely death in February 2007, he was Curator of Historical Archaeology at the New York State Museum in Albany.

A board member of the Warner House Association in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, Louise Richardson is past president of the China Students Club of Boston and has contributed to many publications, including this journal.

Collector, scholar, and graphic designer, Jonathan Rickard wrote Mocha and Related Dipped Wares, 1770–1939 (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2006), the definitive book on dipped wares. Together Rickard and Carpentier have researched pottery sites, wares, and decorative techniques for years, and recently authored “The Little Engine That Could: Adaptation and Use of the Engine-Turned Lathe in the Pottery Industry,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 78–99.

Diana Stradling and her husband, J. Garrison Stradling, are well-known scholars in American glass, pottery, and porcelain, and have authored many books and articles. They spearheaded the efforts to explore the Lewis Pottery site in Louisville, Kentucky, and presented their research results in the first issue of Ceramics in America (2001). Robert Genheimer is the George Rieveschl Curator of Archaeology at the Cincinnati Museum Center in Ohio. A prehistoric and historical archaeologist, he edited Cultures before Contact: The Late Prehistory of Ohio and Surrounding Regions (2000), published by the Ohio Archaeological Council.

Handmade in Ireland, Nicholas Mosse pottery is sponge-decorated by hand. For more information on these ceramics made in the Irish tradition, visit www.nicholasmosse.com.

Denise Carpentier is an independent scholar and master potter who manufactures ceramic reproductions at Eastfield Village.

Susan H. Myers is the Curator Emeritus and C. Malcolm Watkins Chair of the Division of Home and Community Life at the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. She has published numerous articles and curated exhibitions on the production, use, and marketing of American ceramics and glass.

Longtime collector of Long Island redware, Anthony Butera Jr. wrote “‘Informed Conjecture’: Collecting Long Island Redware,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2003), pp. 214–37, and, with coauthors Robert Kissam and Reginald Metcalf, “Long Island Teapots?” pp. 309–12 in this issue.

James Mattozzi, of James Mattozzi Antiques in Groton, Massachusetts, specializes in American furniture, accessories, folk art, and ceramics of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Samples of his inventory may be viewed online at www.grotonantiques.com.

See www.greatamericancraftsmen.org/eastfield/eastfield.htm.