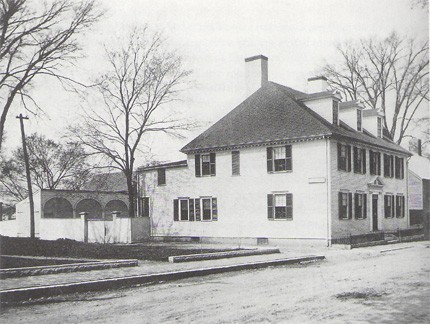

Jacob Wendell house, Pleasant Street, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, built 1789. Photograph by Lafayette Newell and Co., ca. 1902. (Wendell Collection; Image courtesy of Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire.)

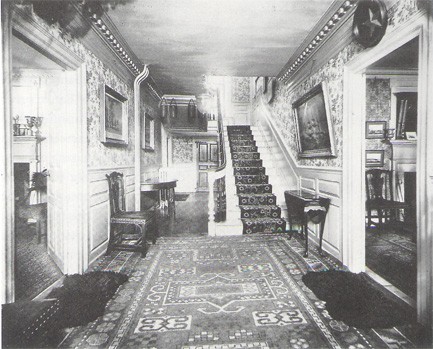

Front hallway, Wendell house. Photograph by Lafayette Newell and Co., ca. 1902. (Wendell Collection; Image courtesy of Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire.)

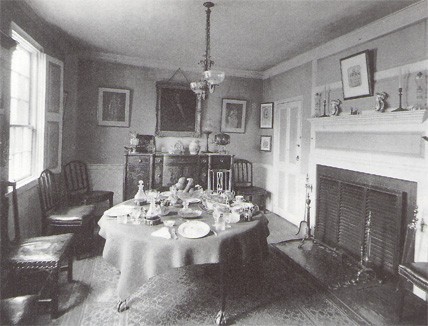

Dining room, Wendell house. Photograph by Arthur T. Greenwood, August 1887. (Courtesy, Ronald Bourgeault.)

Dining room, Wendell house. Photograph, ca. 1900. (Wendell Collection; Image courtesy of Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire.)

Dining room, Wendell house. Photograph by Lafayette Newell and Co., ca. 1902. (Wendell Collection; Image courtesy of Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire.)

Dining room, Wendell house. Photograph by Douglas Armsden, ca. 1940. (Wendell Collection; Image courtesy of Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire.)

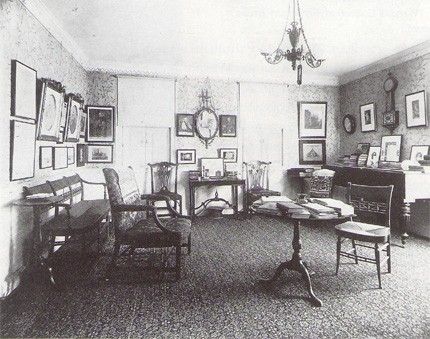

Parlor, Wendell house. Photograph by Lafayette Newell and Co., ca. 1902. (Wendell Collection; Image courtesy of Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire.)

Parlor, Wendell house. Photograph by Lafayette Newell and Co., ca. 1902. (Wendell Collection; Image courtesy of Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire.)

Parlor, Wendell house. Photograph by Douglas Armsden, ca. 1940. (Wendell Collection; Image courtesy of Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire.)

Parlor chamber, Wendell house. Photograph by Lafayette Newell and Co., ca. 1902 (Wendell Collection; Image courtesy of Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire.)

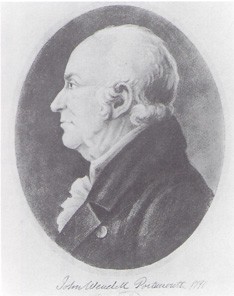

John Wendell (1737—1820). Taken from a modern photograph of a drawing (current location unknown) dated 1791. (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der Woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

High chest of drawers, New England, probably Massachusetts, 1700—1730. Walnut, walnut veneer, and maple with pine. H. 65 1/2", W. 39 3/4, D. 22 1/4. (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der Woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

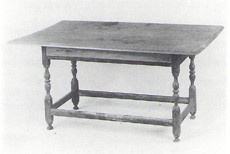

Stretcher-base table, probably Portsmouth, 1740—1780. Maple and pine. H. 27", W. 54", D. 36". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmoutn, New Hampshire; gift of Richard L. Mills; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

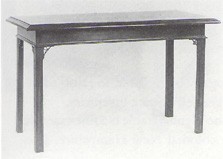

China table attributed to Robert Harrold, Portsmouth, 1760—1775. Mahogany with soft maple and eastern white pine. H. 27 1/4", W. 35 9/16", D. 23 3/8". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der Woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

Side table, Portsmouth, 1760—1777. Mahogany with birch. H. 37", W. 60 3/4", D. 27 1/4". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; lent by Ronald Bourgeault; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

Pair of armchairs, Portsmouth, 1760—1775. Mahogany with birch. H. 40 1/2", W. 27", D. 23". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der oude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

Card table (one of a pair), Portsmouth, 1760—1775. Mahogany with eastern white pine, red pine, and birch. H. 27 5/8", W 35 5/16, D. 17 3/16".(Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

Side chair, Portsmouth, 1760—1790. Birch and maple. H. 35 1/2", W. 21 5/8", D. 16 3/8". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der Woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

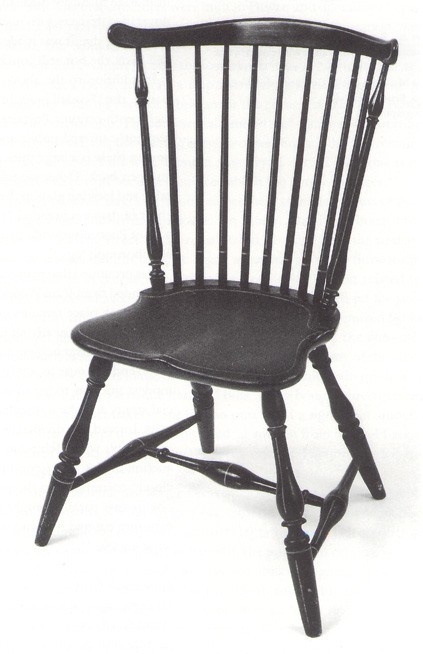

Fan-back Windsor side chair (one of a set of six), branded by Joseph Henzey (b. I743), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, I775—I790. Hickory, white oak, yellow poplar, and soft maple. H. 36 5/8 ", W. 22 7/8", D. I6". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Kenneth E. and Evelyn S. Barrett; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

Box, with three drawers, probable Portsmouth, ca. 1770. Walnut with eastern white pine. H. 14 5/8", W. 11 15/16", D. 17 1/4". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der Woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

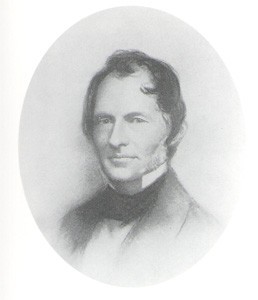

Jacob Wendell (1788—1865). Taken from a modern photograph of a crayon portrait by Seth Wells Cheney (1810—1856) of Boston, ca. 1854. (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der Woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

Chest of drawers, attributed to Langley Boardman (1774—1833), Portsmouth, 1795—1810. Mahogany with eastern white pine. H. 35 3/4", W. 43", D. 22 7/8". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der VVoude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

Card table (one of a pair), by Judkins and Senter (fl. 1808—1826), Portsmouth, 1816. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and rosewood veneer with eastern white pine, birch, and white oak. H. 30", W 37", D. 18". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der Woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

Sofa, by Judkins and Senter, Portsmouth, 1816. Mahogany with beech, birch, eastern white pine, and ash. H. 35 5/8 ", W. 73 3/4 ", D. 24 1/4. (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der Woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

Detail of sofa illustrated in fig. 24. (Photo, New Hampshire Historical Society.)

Sideboard, by Judkins and Senter (fl. 1808—1826), Portsmouth, 1815. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, birch veneer, bird's-eve maple veneer, Casuarina spp. veneer, and light and dark-wood inlays, with eastern white pine, basswood, yellow birch, and unidentified tropical hardwood. H. 43", W. 70 1/2", D. 22 l/8". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der Woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

Lolling chair, Portsmouth, 1815—1825. Mahogany with soft maple and eastern white pine. H. 44", W. 26 3/8". D. 21 3/8". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

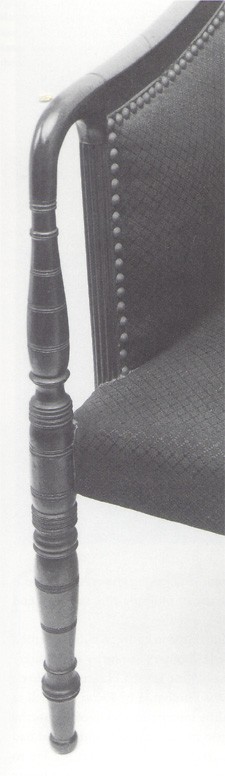

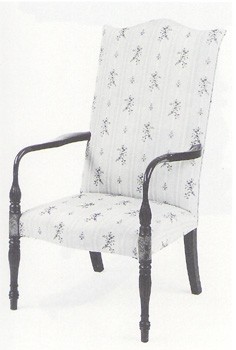

Lolling chair, Portsmouth, 1810—1820. Mahogany and birch veneer with soft maple, beech, and eastern white pine. H. 44", W. 22 1/2", D. 18 1/4". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der Woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

Desk, Portsmouth, 1810—1820. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, birch veneer, and rosewood veneer with eastern white pine. H. 34 1/4", W. 30", D. 17 7/8". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der Woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

Desk illustrated in fig. 29 in open position. (Image courtesy of Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire.) Photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

Card table, Portsmouth, 1820—1825. Mahogany with eastern white pine, basswood, and birch. H. 31", W. 36 1/2", D. 18 1/4". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der Woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

Dressing table and dressing glass, Portsmouth (table) and England or Portsmouth (glass), 1815—1825. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with pine. (Table), H. 37 3/4", W. 39 1/4", D. 18 1/4"; (glass), H. 21 1/4", W. 15 1/4", D. 7 7/8". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der Woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

High-post bedstead, Massachusetts, probably Boston or Salem, 1800—1810, with later cornice, ca. 1830. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and light- and dark-wood inlay with pine. H. 88 3/4, W 56 11/16", D. 79". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der Woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

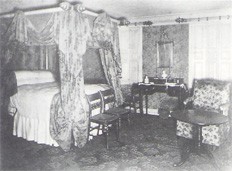

Bedchamber, Wendell house. Photograph by Lafayette Newell and Co., ca. 1902. (Wendell Collection; Image courtesy of Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire.)

Double settee, Portsmouth, ca. 1815. Sweet gum, soft maple, birch, and hickory. H. 35", W. 45 3/4", D. 18". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der Woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

Triple settee, New York City, 1816. Hickory, yellow poplar, soft maple, and ash. H. 34", W. 71 5/8", D. 19 3/4". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der Woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

Armchair, New York City, 1816. Hickory, yellow poplar, soft maple, and ash. H. 33 3/8", W. 19 3/4", D. 16 1/8". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der Woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

Side chair (detail), New York City, 1816. Hickory, yellow poplar, soft maple, and ash. H. 33 5/8", W. 18", D. 16 1/8". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der Woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

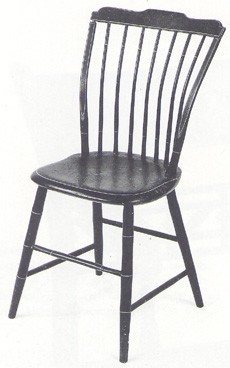

Windsor side chair, Portsmouth, 1815—1820. Later painted decoration by George N. Porter (fl. 1856—1867), Portsmouth, 1856—1860. Birch, eastern white pine, and soft maple. H. 34", W. 15 3/4, D. 15 1/4 ". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der Woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

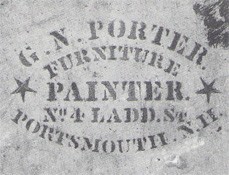

Stenciled label of George N. Porter on bottom of chair illustrated in fig. 39 (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; Photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

Canterbury, by James C. Brown, Portsmouth, 1846 (before restoration). Mahogany and mahogany veneer with eastern white pine. H. 21", W. 20", D. 17". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; gift of Gerrit van der Woude; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

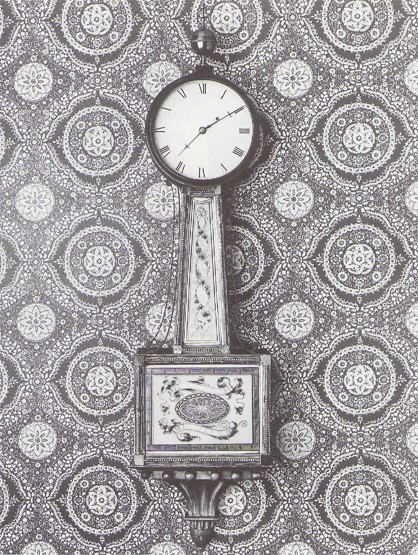

Patent timepiece, by Simon Willard (1753—1848), with painting by John R. Penniman (1782—1841), Boston, Massachusetts, 1811. Mahogany, gilded wood, and glass. H. 43", W. 10 1/2", D. 4". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; lent by Ronald Bourgeault; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

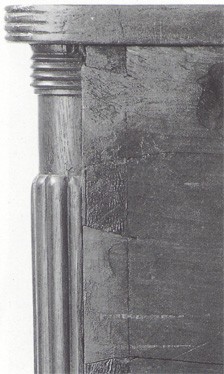

Chest of drawers, Portsmouth, 1815—1820. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with eastern white pine. H. 39", W. 45", D. 20". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; lent by Ronald Bourgeault; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

Back of chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 43. ((Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; Photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

Dining table, Portsmouth, 1810—1820. Mahogany with birch. H. 29 1/4", W. (open) 67 1/2", W. (closed) 17 1/2", D. 56". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; lent by Ronald Bourgeault; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

Cradle, Portsmouth, 1810—1820. Mahogany with pine. H. 26 1/2", W 38", D. 23 1/2". (Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire; lent by Ronald Bourgeault; photo, Bruce Alexander Photography.)

The dwelling on Pleasant Street in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, that became known as the Jacob Wendell house was built by Jeremiah Hill in 1789 (fig. 1) . It is a substantial home, somewhat conservative in plan and ornament, with a wide front hall (fig. 2) and a Georgian floor plan with two generously sized parlors, a dining room, a kitchen, and five bedchambers. The house was purchased by Jacob Wendell (1788—1865) in 1815 and was home (and later summer home) to succeeding family members until 1988: Caroline Quincy Wendell (1820-1890), James Rindge Stanwood (1847—1910), Barrett (1855—1921) and Edith (1859—1938) Wendell, and William G. (1888-1968) and Evelyn (1909-1988) Wendell.[1]

By 1988, when the estate was broken up, the Wendell house had gained a nearly legendary reputation as an "untouched" family collection of antiques. Several series of photographs, including sets taken in 1887,1902, 1912 (with detailed annotations by William G. Wendell), 1940 (again with notations by William G. Wendell), 1966 (by Samuel Chamberlain), and, finally, Strawbery Banke's record shots taken in 1988, show a remarkable continuity of furnishings. Inventories, lists, and appraisals taken in the first half of the nineteenth century and in 1890, 1912, 1968, 1977 and 1988 also document an amazing continuity over time. Adding to the mystique of the house was the successive owners' penchant for preserving family records and for annotating their own history. Particularly important for the purposes of this paper are the business ledgers and invoices preserved in Jacob's papers that document his acquisitions in 1815 and the succeeding years and the later notations of James Rindge Stanwood. As a result, the Wendell collection is exceedingly well documented in collections of papers at Houghton Library and Baker Library at Harvard University, the Portsmouth Athenaeum, and Strawbery Banke Museum's Cumings Library and Archives.

These same pictures and inventories, however, also reveal a good deal of change, both in the arrangement of objects and in the handling of surfaces, including carpets, wallpapers, and paint. Although the family sideboard seems to have had a place of honor in the room used as a dining room, for example, a series of photographs of that room from 1887 (fig. 3), ca. 1900 (fig. 4), 1902 (fig. 5), and 1940 (fig. 6) reveals changes in the chairs, prints, wallpapers, painted woodwork, looking glasses, and other details. A comparison of the family parlor shows similar alterations from 1902 (figs. 7, 8) to 1940 (fig. 9), although one can again trace the presence of major objects, such as the Portsmouth china table (fig. 14) from image to image. Pictures of the large bedchambers (figs. 10, 34) also reflect considerable change and updating of decoration over time. Many of the objects illustrated in this essay can be seen in these earlier pictures.

These images, the various inventories, and other documents also reveal that some objects left the family collection prior to the final breakup in 1988. The Newport oval table with claw-and-ball feet that held such a prominent place in the dining room (see figs. 3, 5) is one such major object. Many others were sold in the late 1970s and early 1980s and have entered private collections. Thus the Wendell house was not intact in 1988, but a high percentage of key objects had been there for a century and a half.

When the house was sold and its contents dispersed in 1988 and 1989, Strawbery Banke Museum was fortunate to receive a large and important collection of furnishings from the house. The vast majority of these were the generous gift of Penelope and Gerrit van der Woude of Eastry, Sandwich, in Kent, England, both family, descendants. The van der Woude gift, which includes ceramics, glass, silver and base-metal objects, paintings, and prints as well as the furniture discussed here, represents the single most important gift of objects to come to Strawbery Banke since its incorporation in 1958.

Other Wendell family materials were given to the museum by Ronald Bourgeault, who recently purchased the house; Bourgeault also loaned several major Wendell family pieces that he acquired. A small number of Wendell family objects were purchased by the museum, and a few with Wendell family associations were already in the Strawbery Banke collection. Those that did not come to Strawbery Banke were sold at auction by Sotheby's in New York in January 1989 at several sales, principally the Important Americana sale, January 26—28 (sale 5810).

Our purpose here is to provide an overview of the Wendell family furniture in the collection of Strawbery Banke Museum. This constellation of objects provides a unique look at the possessions of one New England family. The pivotal figure in the story is Jacob Wendell. As was true for many other New Englanders of his station, Jacob inherited or acquired through marriage many outstanding pieces of colonial furniture. Jacob, like so many in Portsmouth, prospered financially during the federal period and, using his newfound wealth, furnished his home in the mid-1810s with elaborate and fashionable neoclassical furniture, much of it acquired from Portsmouth's leading cabinetmakers. Jacob's financial losses in the late 1820s, although not so severe that he was forced to lose his house, kept him from updating his furnishings during the later part of his life. As was perhaps true in other Portsmouth families, a growing fondness or nostalgia for Portsmouth's heyday of colonial and federal prosperity made Jacob and his heirs look back fondly on the material manifestations of that era, especially the stylish furniture produced in a town dominated by the woodworking trades. Later members of the family, particularly James Rindge Stanwood and Barrett Wendell, were interested in preserving and rehabilitating the relics of the family's earlier glories. By the 1980s, this combination of circumstances and attitudes turned the Wendell house into a form of time capsule.[2]

The Wendell family furniture at Strawbery Banke can be divided into two groups: a small group of objects from the colonial era, many in the rococo style, and a much larger body of furniture from the federal period.

Eighteenth-Century Furniture

The early objects are associated with the time of John Wendell (1731—1808), Jacob's father. John (fig. 11), the son of Major John and Elizabeth (Quincy) Wendell, was born in Boston. After graduating from Harvard College in 1750, he moved to Portsmouth where he developed an active real-estate business. John's two marriages connected him to several of the most prominent families in Portsmouth and suggest a variety of avenues in which the baroque and rococo furniture in the Wendell collection entered the family. John was married first to Sarah, daughter of Captain Daniel and Elizabeth (Frost) Wentworth of Portsmouth. After her death in 1772, he married Dorothy Sherburne in 1778, a much younger woman who was the daughter of the Honorable Henry and Sarah (Warner) Sherburne, also of Portsmouth. The associations through marriage with the Wentworth, Frost, Warner, and Sherburne families connected John Wendell to many of Portsmouth's oldest and most socially prominent families.[3]

This early part of the Wendell collection includes a New England high chest of drawers of circa 1720 (fig. 12). The drawer arrangement and leg turnings suggest that it was made in Massachusetts; however, little is known about Portsmouth furniture of this period. The drawer fronts are veneered with herringbone edge banding and flitches of crotch walnut, whereas the sides of the upper and lower case are solid walnut. The complex cornice moldings disguise a "secret" or document drawer. The high chest was repaired in Portsmouth in the 1880s by John H. Stickney, a local craftsman who repaired many antiques in the Portsmouth area and had a penchant for signing his work. He inscribed the high chest in pencil: "John H. Stickney/Sept 25 1886/Ports N.H." It was probably Stickney who added the current reproduction brasses, replaced the stretchers, and made other repairs.[4]

A mid-eighteenth-century stretcher table with turned legs (fig. 13) was given to the museum by Richard L. Mills of Exeter, New Hampshire, in 1972. According to the donor, this table was found in the Wendell house shed in a bad state of disrepair. Mills felt it was worthy of preservation, and he had a new pine top, drawer, and drawer runners made to fit the surviving maple base. The base has traces of red paint over an earlier coat of black. Similar vase-and-ring leg turnings are found on other tables from the region, including an example branded "J. HAVEN" in the Aldrich Memorial at Strawbery Banke.[5]

A rectangular china table dating 1765-1775 is one of the Portsmouth masterpieces in the Wendell collection and probably the most familiar (fig. 14) . Six other tables by the same cabinetmaker, probably the English immigrant Robert Harrold (fl.1765-1792), are known, and nearly all have strong Portsmouth histories. The construction, woods, and decorative details-carved saltire stretchers, pierced finial, brackets, and rail moldings-of this table are characteristic of this group. Like nearly all of these tables, the Wendell example has lost its original pierced gallery.[6]

The Wendell china table descended en suite with a kettle stand that is now in the collection of the Warner House Association in Portsmouth. According to family tradition, both pieces, along with a large sideboard table (fig. 15), were acquired by John Wendell at the sale of the effects of Sir John Wentworth (1737-1820), New Hampshire's last royal governor, when he fled the colony in 1775. Wentworth lived in a large mansion on Pleasant Street, just south of the Wendell house, and served as governor of New Hampshire between 1766 and 1775. He was a graduate of Harvard College (class of 1755) and took his master's degree there in 1758. After working with his father, he went to England in the early 1760s and was living there when he received his appointment as governor. He returned to America and reached Portsmouth by June 1767. With his aristocratic position, English experience, and significant wealth, Wentworth would have been a likely candidate to acquire locally made furniture in the British taste. This tradition of Wentworth ownership, however plausible, is unconfirmed. The objects could have entered the Wendell family through one of any number of channels. However, it is tempting to speculate that the kettle stand, the china table, and the sideboard table are the same as the "1 Mahogany stand $2 [and] 1 Mahogany large Table $6 [and] 1 Mahogany Sideboard $10" listed in John Wendell's estate inventory.[7]

Based on English and Irish designs, the Wendell table is a fine example of sophisticated rococo design in late colonial New Hampshire. It is particularly important for Strawbery Banke's collection because another china table in the group, now at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was owned originally by Stephen Chase (1742-1805), a Portsmouth merchant and owner of Strawbery Banke's Chase House (built in 1762) from 1799 until his death. Chase's china table probably was the object listed in his inventory as a 3' mahogany table valued at $4.50 and located in his parlor; it appears in the inventory just before an itemization of tea wares.[8]

The pair of upholstered armchairs illustrated in figure 16 probably were made in Portsmouth in the 1760s or 1770s, also in a very English style, having low proportions, broad seats, and curved or swelled front seat rails. Although these have their original upholstery foundations, they were recovered in 1912-1913 in a "handsome red brocade." Slipcovers (made of a Schumacher reproduction of a 1775-1785 English plate-printed textile and fashioned after a design depicted in John Hamilton Mortimer's Sergeant-at-Arms Bonfog; His Son, and John Clementson, Sr., ca. 1770) recently were made to cover the soiled brocade. The use of birch as a secondary wood confirms the American origin of these armchairs, and they are related to a relatively large group of chairs with Portsmouth histories. Like the china table, they reflect the sophisticated English-dominated taste in Portsmouth in the 1760s.[9]

Dating to about the same time, and again probably made in Portsmouth, are a pair of rococo card tables (fig. 17) with Marlborough legs strongly related to those on the china table and sideboard table and with a somewhat unusual wide drawer. William G. Wendell's notes of 1912 indicate that "these tables were in different parts of the house, one being used as a washstand, the other as a tool chest," which may well account for the legs of each having been shortened. The family reclaimed them from their "degradation" (as they put it), had them repaired, and placed them in a parlor.[10]

The rococo side chair illustrated in figure 18 dates 1760-1790. Its legs also have been cut down (about 1"), its side stretchers have been replaced, and its slip seat has modern upholstery over the original frame; however, this chair is significant as a representation of a simple pierced splat and a "Chinese" crest rail that are common Portsmouth patterns.[11]

Six fan-back Windsor side chairs (fig. 19) also are among the early Wendell objects in the collection. Four bear the brand of Joseph Henzey, a noted Windsor chairmaker of Philadelphia; one is unmarked; and the sixth, in poor condition, is branded by James C. Tuttle (ca. 1772-1849) of Salem, Massachusetts. Originally painted green, the chairs are now painted black with gold striping. All seem to have been together since the date of this repainting, probably in the late nineteenth century, and all have a history in the Tibbetts house, just north of the Wendell house on Pleasant Street. It is likely that they came to Portsmouth in the eighteenth century as part of Henzey's large export trade. William G. Wendell probably acquired them as antiques; he gave them as a wedding present in 1953 to his stepdaughter Evelyn and her husband, Kenneth E. Barrett. [12]

A small box with three drawers (fig. 20) represents a type of common, utilitarian furniture made in Portsmouth that rarely survives. It has three dovetailed drawers with rosehead nails securing the bottoms to the backs, suggesting that it was made before 1790. When it was found in the Wendell barn, the box still contained papers and documents.

In addition to the above-mentioned objects that came to Strawbery Banke, the Wendell household included many other important pieces of eighteenth-century Portsmouth and New England furniture that subsequently entered public and private collections. Perhaps most notable among these is a large upholstered rococo couch with scrolled ends and an open back. Other significant early objects are a mahogany dressing table and looking glass in the late baroque style, a Portsmouth blockfront chest of drawers branded "I. SALTER," probably for its original owner, a set of Portsmouth side chairs with pierced splats, and a basin stand with Marlborough legs.[13]

It is presumed that many of these eighteenth-century objects eventually descended from John Wendell to his son, Jacob, although how this transaction took place remains unclear. John's will, written in 1808, the year of his death, left nearly all his estate, including all his real and personal property, to his much-younger wife Dorothy, who continued to live in the Wendell house as a widow. At her death in 1838, Dorothy left only modest amounts to her sons in her will, since they were in difficult financial straits and she wished to avoid having her legacy attached by creditors. Instead, she divided her estate among her daughters-in-law, including Jacob's wife Mehitable. Most of Dorothy's personal goods sold at auction in 1838. The items in her inventory and in the auction list do not closely correspond to the objects later in the Wendell house, although one or two parallels might be drawn. Thus exactly how this cluster of furniture entered into and descended through the family remains somewhat unclear.[14]

Nineteenth-Century Furniture

Understanding the acquisition of the nineteenth-century furniture in the Wendell collection is much more straightforward, although not without its pitfalls in the slippery business of linking surviving objects with terse descriptions in inventories or invoices. The records of Jacob Wendell provide numerous opportunities for identifying the date, source, and original cost of many pieces of family furniture.

Jacob (fig. 21) was the sixth child born to John and Dorothy Wendell. At the time of his birth in 1788, the family fortunes were diminished. Although John intended to send his sons to Harvard, this proved financially impossible, and Jacob was educated in Portsmouth. After completing his education Jacob entered business life and shortly became a merchant and importer of Russian and West Indies goods. His first successes came during the War of 1812, when he profited through privateering and various shipping ventures. He turned from shipping to manufacturing and, in 1815 at the age of twenty-seven, he entered into business with his brother Isaac and others to establish cotton mills on several of the rivers that feed Great Bay. The first structures were built in Dover, and operations began in 1821. Two years later, another mill, the Great Falls Corporation, was built on the Salmon Falls River. For several years these enterprises flourished and brought Jacob handsome profits. [15]

In the 1820s Jacob also ran a ship chandlery and hardware store in partnership with his brother Abraham at the corner of State and Water streets in Portsmouth. The commercial panic of 1827-1828 had devastating effects, however, crippling the Wendell brothers financially. The remaining years of Jacob's life were spent in a variety of clerical positions as he attempted to pay off his debts and reestablish the family fortunes.[16]

During the early stages of Jacob's career, he was in the process of purchasing a home and setting up house. On June 21, 1815, Jacob bought the house on Pleasant Street which remained in his family for the next 173 years. About six months later, he began acquiring goods to furnish this large dwelling. A ledger dated 1814-1827 includes a section related to Jacob's household accounts. It is headed "Account of cash pd for sundries for furnishing my house Jan 7, 1816," and includes an itemized list of household goods purchased and services paid for during the 1816-1827 period, such as furnishings, food, clothing, and labor. Many of the nineteenth-century objects in the house can be related to entries in this ledger and, occasionally, to separate itemized bills. Jacob bought directly from Portsmouth cabinetmakers, but he also purchased a significant amount of furniture, some of it presumably used, at auction from Samuel Larkin and others. Jacob also occasionally went outside Portsmouth for his purchases. [17]

On August 16, 1816, just about a year after he bought the house, Jacob married Mehitable Rindge Rogers (d. 1859), the only child of Mark and Sarah (Rindge) Rogers of Portsmouth. (Her father was a first cousin, on his mother's side, of Sir John Wentworth, the purported original owner of the china table [fig. 14] and other rococo objects, suggesting another way in which they entered the family.) Jacob and Mehitable lived the remainder of their lives together in their Pleasant Street home.[18]

The nineteenth-century furniture from the Wendell family is rich in its associations with local makers and diverse in its variety of forms and materials. One of the earlier examples is a mahogany chest of drawers with a serpentine front and canted front corners (fig. 22). This characteristic Portsmouth example is part of a group that includes a chest at the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities's Rundlet-May House thought to have been purchased in 1802 by James Rundlet from the cabinetmaker Langley Boardman (1774-1833). Boardman was a wellknown local craftsman, and this chest of drawers joins a significant group of work from his shop already, at Strawbery Banke, including a massive sideboard, a secretary, and a group of chairs. The Wendell chest lacks the string inlay and quarter-fans found on some examples, but otherwise conforms to the norm for these large, bold chests. The mid-eighteenth century plate brasses are replacements, probably added at the instigation of James Stanwood or Barrett Wendell in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century with the thought that the chest was made a generation earlier than is actually the case. [19]

Figuring prominently in this body of furnishings is a subgroup of furniture acquired by Jacob from the Portsmouth cabinetmaking firm of Jonathan Judkins (1780-1844) and William Senter (1783-1827), active at a variety of locations on State Street from 1808 to 1826. These include a pair of mahogany card tables (fig. 23) and a mahogany sofa (fig. 24) sold to Jacob on June 7, 1816, for a total of $70, and paid for by him on July 31. The card tables are square with an elliptic front, half-elliptic ends, and ovolo corners, a design often used in Portsmouth card tables and dressing tables and echoed in the configuration of the sideboard discussed below. The tables are distinguished by the use of rosewood veneer and by their pointed, ebonized feet. The sofa (covered with twentieth-century horsehair upholstery) has multiple horizontal reeds along the crest rail and is related to the card tables through the use of multiple ring turnings and incised rings on the legs (fig. 25).[20]

The Judkins and Senter sideboard illustrated in figure 26 is documented in several ways. It is signed "Made/& [?]/January as/1815/by J & Senter" and bears the brand "J. HAVEN," possibly for Joshua Haven, who lived in the Pleasant Street home when it was purchased by Jacob Wendell in June 1815, or for Joseph Haven, a wealthy merchant who lived across the street from the Wendell house from 1780 to 1820. Judkins and Senter had reacquired the chest by December 20, 1815, when they sold it for $70 to Jacob. (One wonders if the sideboard was merely left behind in the house by Joshua Haven.) Jacob's ledger notes "Cash pd. Side Board—$70—" on January 1,1816. A drawer in the sideboard also bears later inscriptions, difficult to decipher, but that include the name "George Wendell" and the date of "July 18, 1838," each written twice. The handwriting of these is a somewhat childish scrawl, and the inscriptions may represent the doodling of Jacob's son, George Blunt Wendell, who was age seven in 1838.[21]

The sideboard, like the high chest (fig. 12) and other Wendell furniture, was repaired by a local craftsman in the late nineteenth century, probablv at the urging of family descendant James R. Stanwood (1847-1910), who lived in the house nearly his whole life. A penciled inscription on the underside of the top reads: "Repaired by John H. Stickney May 25, 1887, in the Old Custom House Penhallow St. Portsmouth, N.H." A century later, the sideboard was treated by the Boston conservation firm of Robert Mussey, whose work brought back to light the magnificent color contrasts that had been obscured by years of dirt and discoloration.[22]

Jacob's other purchases from Judkins and Senter included, along with repair work and a variety of tasks, a secretary valued at $36 (private collection) on September 6,1813, a bedstead priced at $19 (private collection), a set of chairs ($28), a table and stand ($11.50), a work table ($10), a second table and stand ($14.50), "pieces round hearth" ($1.50), a bed cornice ($13), a window cornice ($7.50), and a bed top ($2) documented in the bill of May 10,1816, that includes the sideboard, sofa, and card tables now at Strawbery Banke.[23]

Two Portsmouth lolling chairs probably were acquired by Jacob during the 1810s—1820s. One (fig. 27) is still covered in its original black horsehair upholstery secured by cast-brass nails and has mahogany arms and legs with ring turnings and carving. It closely resembles an example at the Rundlet-May house that shares the same curved arms and style of carving and was owned originally by Samuel Lord of Portsmouth. The second (fig. 28) has been reupholstered (in a modern yellow brocade given to Edith Wendell by Henry Francis du Pont) and has mahogany arms and legs embellished with a band of inlaid figured birch at the juncture of the front and side seat rails. This chair bears an ink inscription reading $12 on the inside of the rear seat rail, perhaps an indication of the original price of the chair or the chair frame.[24]

Figured birch also distinguishes a small desk (fig. 29) that exhibits the strong color contrasts so typical of Portsmouth furniture, created by playing dark mahogany and rosewood veneer against light, figured birch veneer. The desk, which is made as one piece, opens to reveal a slanted writing surface originally covered with broadcloth and a row of small drawers for writing implements; the upper writing flap conceals a row of pigeonholes in the compartment underneath (fig. 30).[25]

Two objects in the collection may date from the 1820s. One, a mahogany card table (fig. 31), might well be the "Grecean card table" Jacob purchased from an unspecified source for $17.50 in September 1821. The four arched legs terminating in volutes and twin acanthus-carved pedestals suggest that this table would have been considered Grecian in the 1820s. Its shape and basswood secondary wood points toward a New Hampshire origin. The leaves of the top, when opened, swivel to lie flat for gaming. The second, a dressing table (fig. 32), is also of mahogany and has elaborate turned legs. It is distinguished by having its original dressing box, which is fitted to the top of the table. On September 29,1825, Jacob Wendell bought at auction a "mahogany dressing table" for $12.25, which conceivably could be this object, especially since the heavy ring and twist turnings of the legs suggest this date. For many years the dressing table has been associated with a small dressing glass, possibly from Portsmouth or England .[26]

Although Jacob patronized Portsmouth firms frequently, he occasionally purchased objects produced in other areas. A case in point is a mahogany bed (fig. 33), probably made in Massachusetts. Although Jacob purchased some beds locally, from Judkins and Senter and others, the carving, inlay, and other details of this bed point to an origin in Boston or Salem. Whereas the carved and inlaid footposts are fashioned in a delicate manner typical of the 1800-1810 period, the thick cornice rods and bulbous gilt terminals clearly are later additions. William G. Wendell described this cornice as consisting of "heavy bars of wood, round, painted white and terminating in fluted bulbs, gilded. These bars matched the curtain bars over the windows [also now at Strawbery Banke], and were used to support heavy curtains in winter." These early bed hangings and the Window curtain bars can be seen in a 1902 picture of a bedchamber (fig. 34).[27]

The collection is enhanced by the presence of two large sets of fancy painted seating furniture. One set, known in the family for obvious reasons as the "red set," includes eight side chairs, two armchairs, and two double settees that probably are of Portsmouth manufacture (fig. 35). They resemble a set of six chairs acquired by James Rundlet in 1806 from James Folsom of Portsmouth at a cost of $4 each. The red set has a curious history. In 1912, William G. Wendell noted that "this set was formerly in the best parlor (sitting room) and was painted white and gold. It had gotten into rather shabby condition, as regards the paint but the frame and seats were in good order. Many of the chairs, however, had been relegated to the attic. In 1912 one of the chairs was sent to a local furniture painter, to be repainted, with a view of retouching the entire set. In scraping off the white and gold paint the man came upon an entirely different pattern underneath, showing the chairs originally to have been painted red and gold. The design on the back of the chairs is that of three ostrich plumes with ends curving." The entire set was repainted red and gold in 1913, following the original design. [28]

The second set of chairs, however, has survived in pristine condition. It includes two armchairs, twelve side chairs, and a triple-back settee (figs. 36, 37). They are painted in gold and black, with eagles on the crest rail (fig. 38) and a row of floral decoration along the seat rails. Although the basic formula for the decoration on each crest rail is consistent-an eagle, two leaves and tendrils, and a cluster of berries-the execution varies considerably from chair to chair, with minor differences evident, for example, in the number and composition of the berries. (It is possible that the leaves and stylized berries depicted are strawberries, since they resemble the ones depicted on polychrome painted pearlware of the period.) This set was purchased by Jacob in January 1816 from Bailey and Willis, retail merchants at 109 Front Street in New York City. He paid $30 for the settee, $5.25 apiece for the fourteen chairs, and $2.50 for packing (described as "bandages" in Jacob's ledger) to have the chairs shipped from New York City on board the schooner Friendship. Jacob's order also included dry white lead and pork, suggesting that Bailey and Willis were retail merchants rather than furniture makers.[29]

Because of the large number of chairs, the unusual triple settee, and the distinctive decoration of the set, the "gilt" or "eagle gilt" suite can be traced easily in various house inventories and lists. Caroline Quince Wendell's inventory, taken in 1890, listed these pieces in the south parlor and described them as "a rush-bottomed set in buff, with gilt ornamentation, each piece bearing a design upon the back representing an Eagle grasping his prey, specified as follows: 1 Settee, triple design, 2 Armchairs, 12 chairs."[30]

Three Windsor side chairs and one armchair, fitted with rockers, from another group of chairs also came to Strawbery Banke (fig. 39). A stenciled label (fig. 40) on the underside of the seat of several of them reads "G. N. PORTER/FURNITURE/PAINTER/NO 4 LADD ST./PORTSMOUTH, N.H." Porter was active in the mid-nineteenth century and was responsible for one of the four coats of paint these chairs have had. Whether or not he did the current coat (green with yellow striping and lyres flanked by flowers at the center of the crest rail) is unclear. Porter is listed in the Portsmouth city directories at the 4 Ladd Street address in 1856-1857 but had moved to 7 Ladd Street by the time of the 1860-1861 directory. He is listed in the directories in 1867, but not in 1873.[31]

One unusual later object in the house is a canterbury (fig. 41), a form uncommon in American furniture, named (according to tradition) for one of the archbishops of Canterbury and used to hold sheet music. It has a penciled signature on the underside of the drawer that reads "J. C. Brown/Maker/March 21st 1846." In the 1850s, James C. Brown lived on Court Street and worked as a cabinetmaker for the firm of E. M. Brown and Company on Market Street. He may have made the canterbury while working on his own in the 1840s, although information about his career remains sparse.[32]

Although the Wendell furnishings that did not come to Strawbery Banke were scattered widely in 1988 and 1989, an important group was acquired by Ronald Bourgeault, who also purchased the house from the family's estate. Bourgeault generously loaned five pieces of furniture to Strawbery Banke, including a timepiece with a gilt case and eglomise panels (fig. 42), one of which is inscribed "S. WILLARD'S PATENT." The clock is additionally documented on the back of the throat panel, "Painted by John R. Penniman, Boston, May 1st, 1811" and on the back of the eglomise panel on the door "Enamelled by John R. Penniman, Boston, May 1, 1811." According to Penniman scholar Carol Damon Andrews, these are the "only such panels [Penniman] is known to have signed and dated." The clock seems to have been in the parlor since at least the 1830s, and it hangs in the same position against the south wall in all photographs. It may have been purchased at auction by Jacob.[33]

The Bourgeault loan also includes a mahogany chest of drawers (fig. 43) with an elliptic front and ovolo corners, reeded columns, and turned feet characteristic of Portsmouth work. The chest is distinguished by having backboards that are dovetailed to the sides (fig. 44) rather than nailed into a rabbet. A large dining table (fig. 45), also loaned by Bourgeault, has six legs and deep hinged leaves supported on each side by two fly legs. The legs are decorated with simple ring turnings.[34]

A mahogany cradle (fig. 46) may be by Judkins and Senter. (Jacob and Mehitable had eight children born between 1817 and 1831.) On June 10, 1817, Judkins and Senter billed Jacob $10 for a "Cradle (Mahogany)" but noted on the bill that he would receive a $1 "discount on cradle." Jacob was cutting it close; his first son, Mark Rogers, was born on June 18. A "Mahogany Cradle" valued at $9 was subsequently entered on Jacob's ledger for August 16, 1817.[35]

The Wendells were not alone in Portsmouth, of course, in preserving their family homestead and treasuring their family possessions. The Wendell "experience" in this regard forms a remarkable parallel, in many respects, to that of the house built by James Rundlet on Middle Street in 1807-1808 and now owned by the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities.[36] Fortunately, the Rundlet-May house has survived with its furnishings more or less intact, and they, too, are documented in the business papers of their original owner. But such instances are indeed rare and therefore the more to be treasured. The Wendell collection presents a challenging opportunity for ongoing research, as the process of matching bills, receipts, and inventories with surviving objects continues and as our understanding of Portsmouth cabinetmaking and taste increases in depth.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are deeply grateful to Brock Jobe and staff of the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (SPNEA) for generously sharing their research on Portsmouth furniture. Jobe's catalogue contains more detailed information on the ornamental and construction characteristics of Portsmouth furniture than is possible to give here and will place the Wendell objects into a deeper context. We are also grateful to SPNEA for sharing the results of R. Bruce Hoadley's wood analysis on many of the objects illustrated here. Any mistakes in identification or attribution made here are the sole responsibility of the authors. We are also indebted to Jane C. Nylander, Carolyn Parsons Roy, Rodney Rowland, and Greg Colati at Strawbery Banke Museum; to the librarians at the Baker Library, Harvard Business School, and the Portsmouth Athenaeum; to Ronald Bourgeault; and to Mr. and Mrs. K. E. Barrett for their assistance.

The Wendell house, family, and furnishings are the subject of research by Strawbery Banke Museum on a wide variety of fronts. For a capsule history of the house and its owners, see the entry by Jane C. Nylander in Sarah L. Giffen and Kevin D. Murphy, eds., "A Noble and Diqnified Stream": The Piscataqua Region in the Colonial Revival, 1860-1930 (York, Me.: Old York Historical Society, 1992), cat. 4; an entry by Anne Masury (cat. 24) on the Wendell gardens is in the same volume. The Wendell house is discussed in James Leo Garvin, "Academic Architecture and the Building Trades in the Piscataqua Region of New Hampshire and Maine, M5-i815" (Ph.D. dissertation, Boston University, 1983), pp. 304-6.

For John Wendell, see his biography in Clifford K. Shipton, Biographical Sketches of Those Who Attended Harvard College in the Classes 1746-1750 with Bibliographical and Other Notes, Sibley's Harvard Graduates, vol. 12 (1746-1750) (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1962), pp. 592-97. For society in colonial Portsmouth, see James L. Garvin, "Portsmouth and the Piscataqua: Social History and Material Culture," Historical New Hampshire 26, no. 2 (Summer 1971): 3-48, and Charles E. Clark, The Eastern Frontier: The Settlement of Northern New England, 1610-1763 (New York: Knopf, 1970).

Stickney is listed as a cabinetmaker and furniture repairer in the Portsmouth city directories from 1860-1861 until 1901.

The Chase china table is illustrated in Morrison H. Heckscher and Leslie Greene Bowman, American Rococo, 1750-1775: Elegance in Ornament (New York and Los Angeles: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1992), cat. 102. Chase's inventory is in Rockingham County Probate Records, Exeter, New Hampshire, docket 7381.

The authors are grateful to Brock W. Jobe for sharing information about this important group of Portsmouth upholstered chairs. The Wendell family also owned a related chair; see Important Americana, lot 1451. The Mortimer painting is in the collection of the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Conn. The SPNEA owns a very similar English chair.

See Brock W. Jobe and Myrna Kaye, New England Furniture: The Colonial Era, Selections from the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1984), cat. 126

For Henzey and Tuttle, see Charles Santore, The Windsor Style in America, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: Running Press, 1987), 2: 254., 267. See also Philadelphia: Three Centuries of American Art (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1976), pp. 156-58.

For more on the couch now in the Winterthur Museum, see Robert F. Trent, "The Wendell Couch," Maine Antique Digest 19, no. 2 (February 1991): 34D-37D. The dressing table (lot 1453) and chest of drawers (lot 1454) are illustrated in Important Americana; see also lot 1449 (basin table). The rococo side chairs are in a private collection.

Alexander Du Bin, Wendell Family (Philadelphia: Historical Publication Society, n.d.), p. 5. For John's later career, see his biography in Sibley's Harvard Graduates noted above. Jacob's life is amply documented in the family papers at the Portsmouth Athenaeum and the Baker Library at the Harvard Business School. Capsule information is given in James Rindge Stanwood, Direct Ancestry of the Late Jacob Wendell of Portsmouth, New Hampshire (Boston: David Clapp & Son, 1882), pp. 28-31.

Stanwood, Direct Ancestry of the Late Jacob Wendell, pp. 29-30.

Stanwood, Direct Ancestry of the Late Jacob Wendell, pp. 30-31. For the Wentworth connection, see M. A. DeWolfe Howe, Barrett Wendell and His Letters (Boston: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1924), p. 8.

The Rundlet chest is illustrated in Penny J. Sander, ed., Elegant Embellishments: Furnishings from New England Homes, 1660-1860 (Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1982), cat. 59. See also Brock W. Jobe's entry on the form in Rollins, Treasures of State, cat. 115. For Boardman, see Plain and Elegant, Rich and Common: Documented New Hampshire Furniture (Concord: New Hampshire Historical Society, 1979), pp. 141-42. Furniture associated with Boardman in the Strawbery Banke collection includes a set of chairs (1974.4-3-44), a sideboard (1974.653), and a secretary (1983.6) inscribed by Ebenezer Lord as having been made in Boardman's shop.

Documented New Hampshire Furniture, cat. 7. A closely related example is in the collection of the New Hampshire Historical Society. The deed that recorded when Jacob bought the house mentions that it is "now in the occupation of Joshua Haven"; see Rockingham County Registry of Deeds, Exeter, New Hampshire, 207:170. Joseph Haven lived across the street from the Wendell house; see Charles Caleb Gurney, Portsmouth Historic and Picturesque (1902; reprint, Portsmouth, N.H.: Strawbery Banke, Inc., 1981), p. 8o. The various possibilities concerning the J. Haven brand are discussed in Myrna Kaye, "Marked Portsmouth Furniture," Antiques 113, no. 5 (May 1978): 1101 -2.

These bills are in case 13, folder 4, Wendell papers, Baker Library.

This chair apparently was a favorite of Edith Wendell's, who was photographed in it ca. 1930 holding her pet dog. Among the many related examples are chairs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bayou Bend, the Anglo-American Art Museum in Baton Rouge, and ones illustrated in American Antiques from Israel Sack Collection, 9 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Highland House Publishers, 1976), 5: 4210, and Oscar P. Fitzgerald, Three Centuries of American Furniture (New York: Gramercy Publishing Company, 1985), fig. V-7, p. 90.

It has not been possible to pinpoint the acquisition of this object in Jacob's papers. He purchased "I Gentleman's writing desk" at auction for $9.25 on July 31, 1813 (Jacob Wendell papers, Baker Library, IB-6, folder 4), but this form is usually called a lady's writing desk (see Charles F. Montgomery, American Furniture: The Federal Period in the Henry Francis du Pont Wintertbur Museum [New York: Viking, 1966], cat. 193). For other related examples, see American Antiques from Israel Sack Collection, I: 470, 2: 801, 7: 5,315; and Edwin J. Hipkiss, Eighteenth-Century American Arts: The M. and M. Karolik Collection (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press for the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1941), cat. 31.

Ledger 2, p. 62. The bill is in the Wendell papers at the Baker Library. The shape of the card table (square with an elliptic front and half-elliptic ends) was found only rarely by Benjamin A. Hewitt on earlier tables with turned and straight legs, and then only on tables from Salem, Massachusetts, and northward (Hewitt, Kane, and Ward, The Work of Many Hands, pp. 69, 188). A painted table and washstand originally owned by Jacob are illustrated in Antiques 128, no. 3 (September 1985): 347. A painted dressing table, originally owned by Abraham Wendell, was acquired by the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center in 1974; it is discussed in a letter from Richard Miller, Associate Curator, December 19, 1989, Strawbery Banke curatorial files.

The bed is described in William G. Wendell, "The Jacob Wendell House," p. 35. For a remarkably similar example attributed to Boston or Salem, see Montgomery, American Furniture, cat. I. It is not clear that the cornice rods have always been associated with the bed now at Strawbery Banke, although such was the case in 1988.

For the Folsom chairs, see Documented New Hampshire Furniture, cat. 5. William G. Wendell, "The Jacob Wendell House," p. 31. For a view of a settee prior to repainting, see Luke Vincent Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America, 2nd ed. (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1913), fig. 635; a side chair after repainting is illustrated in fig. 604. An 1890 inventory described them as being "white, with foliated ornamentation in gilt and black"; see a photocopy of a manuscript copy of the "Inventory of Furniture, Etc., Belonging to the Personal Estate of Caroline Quincy Wendell," in the handwriting of James Stanwood, in the Strawbery Banke curatorial files. In May Of 1992 Strawbery Banke purchased a pair of red Portsmouth fancy painted side chairs with rush seats with a history in the family of Mr. and Mrs. Barrett ("Bud") Wendell of Beverly Farms, Massachusetts.

Benjamin Bailey and Walter Willis are listed as partners in New York City directories at 109 Front Street in the 1810s. We are grateful to Deborah Dependahl Waters for providing information on Bailey and Willis; see her letter of May 23, 1991, in the object file 1980.230. Bailey and Willis's bill is in the Jacob Wendell papers at Baker Library; the purchase also is recorded in Ledger 2, p. 63. Related chairs have been published in many works, including Roderic H. Blackburn, Cherry Hill: The History and Collections of a Van Rensselaer Family (1976), p. 86 (including a triple settee); Fine American Furniture, sale 5883 (New York: Sotheby's, June 21, 1989), lot 346 (very similar side chairs); Zilla Rider Lea, ed., The Ornamented Chair: Its Development in America (1700-1890) (Rutland, Vt.: Tuttle, 1960), figs. 25, 33, 34.

Portsmouth city directories. Porter's ad in the 1867 directory refers to him as a "Furniture & House Painter, and Grainer." Strawbery Banke's collection also includes a pair of chairs with a history in the Goodwin family; one with Porter's stencil and the other branded by J. and G. Brown.

The bill for the cradle is in the Jacob Wendell papers at Baker Library; the corresponding ledger entry is in Ledger 2, p. 61. Jacob's children are listed in Stanwood, The Direct Ancestry of the Late Jacob Wendell, p. 31 The cradle was acquired by the current owner directly from the Wendell estate. In 1988, it was located in a storage area on the second floor of the barn at the rear of the house.