Racket Shreve excavating the Captain Stephen Phillips trash pit, Salem, Massachusetts, 1974–1976. (Courtesy, Racket Shreve.)

James Frothingham, Captain Stephen Phillips, Salem, Mass., ca. 1818–1826. Oil on canvas, 34 3/4" x 29 3/4". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum.)

Michele Felice Cornè, Ship John, Salem, Massachusetts, 1803. Watercolor, 17 1/4" x 23 1/4". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum.)

Number 17 Chestnut Street, the Captain Stephen Phillips House, 2005. (Photo, George Schwartz.)

Selected examples of the ceramic and glass assemblage excavated from the Phillips trash pit. (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum; unless otherwise noted, all artifact photographs by Walter Silver.)

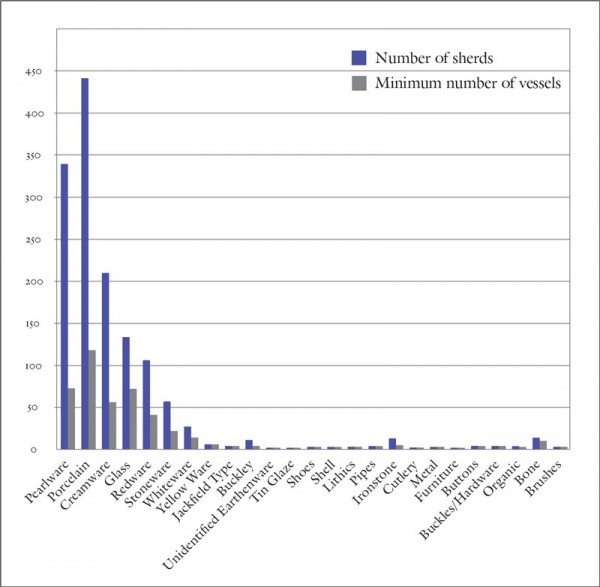

Distribution of artifacts recovered from the Phillips trash pit.

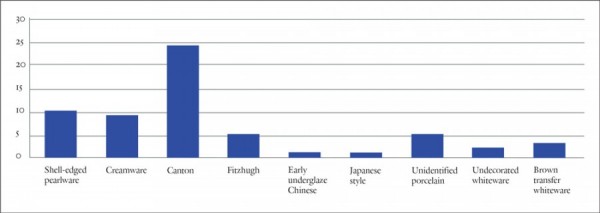

Distribution by ceramic type of plates recovered from the Phillips trash pit.

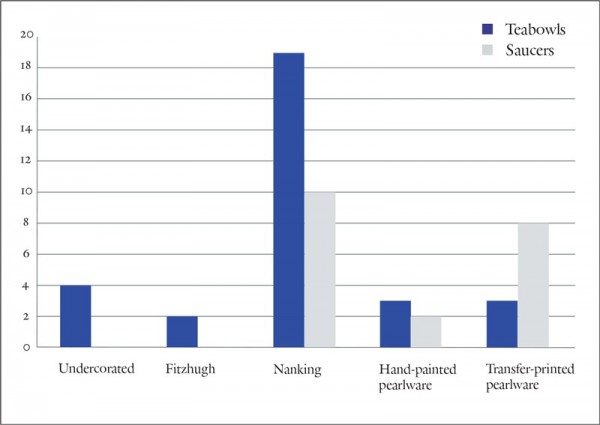

Teabowls and saucers recovered from the Phillips trash pit.

Selected examples of the Chinese porcelain recovered from the Phillips trash pit. (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum.)

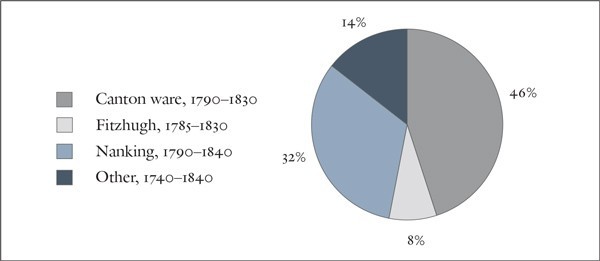

Types of Chinese porcelain recovered from the Phillips trash pit.

Teabowl and saucer, China, 1760–1780, recovered from the Phillips trash pit. Hard-paste porcelain with underglaze-blue decoration in the Nanking style. D. of bowl 3 1/2", D. of saucer 5 1/2".

Plate, China, 1790–1820, recovered from the Phillips trash pit. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 5 3/4". The rim of this low-quality Canton-style porcelain is heavily pitted.

Plate fragments, China, ca. 1750, recovered from the Phillips trash pit. Hard-paste porcelain.

Plate fragment, China, 1750–1765, recovered from the Phillips trash pit. Hard-paste porcelain. This fragment, from an overglazed Japanese-style porcelain plate, shows the leg of a bird (see arrow) similar to one on the soup plate illustrated in fig. 15.

Soup plate, China, 1750–1765, illustrated in Daniel Nadler, China to Order (Paris: Vilo International, 2001), p. 83, pl. 74.

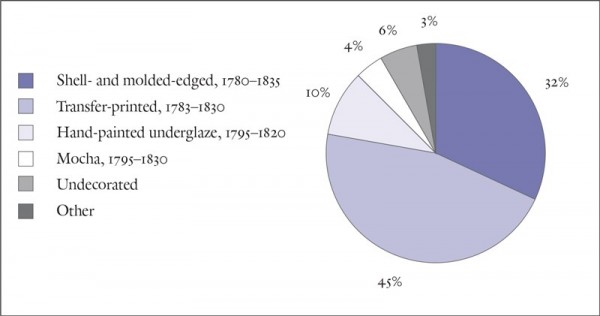

Types of pearlware recovered from the Phillips trash pit.

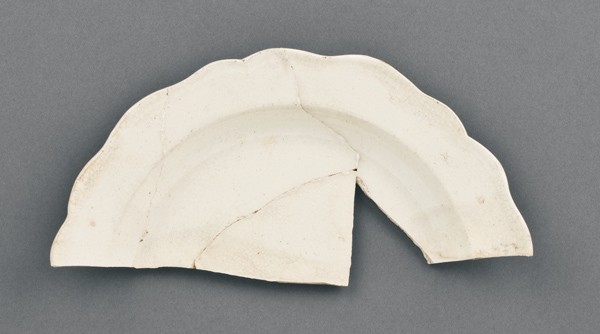

Plate, probably Staffordshire, England, 1780–1810, recovered from the Phillips trash pit. Pearlware. D. 7".

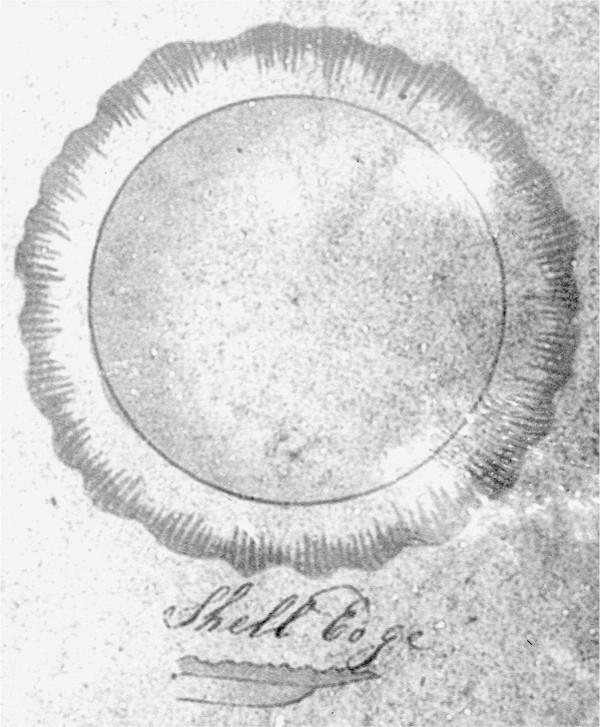

Shell-edged plate illustrated in Josiah Wedgwood’s 1802 trade catalog. (Courtesy, Birmingham Museum of Art.)

Saucers, England, 1785–1810, recovered from the Phillips trash pit. Pearlware or China glaze. D. 6".

Teabowl and saucer, Staffordshire, England, 1810–?, recovered from the Phillips trash pit. Pearlware or China glaze. D. of teabowl 3 1/2", D. of saucer 5 1/4".

Chamber pot, possibly Staffordshire, England, 1785–1810, recovered from the Phillips trash pit. Pearlware in the scratch-blue style. H. 5 1/2". Mark: “GR” on side.

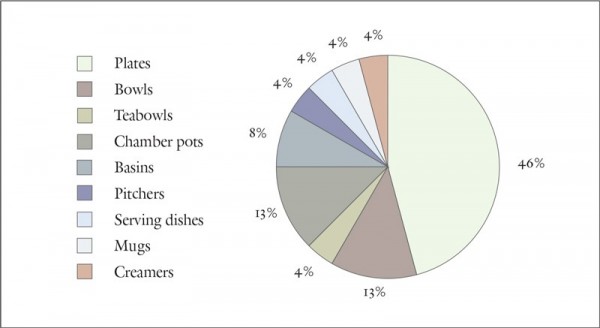

Types of creamware vessels recovered from the Phillips trash pit.

Plate, probably Staffordshire, England, 1790–1810, recovered from the Phillips trash pit. Creamware in the Flat Rim style. D. 8 1/2".

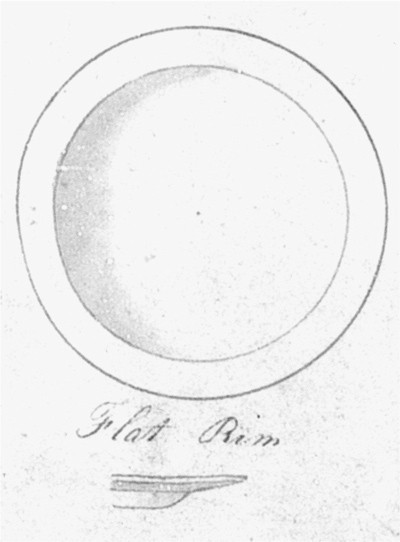

Flat-rim creamware plate illustrated in Josiah Wedgwood’s 1802 sale catalog. (Courtesy, Birmingham Museum of Art.)

Plate, probably Staffordshire, England, 1790–1810, recovered from the Phillips trash pit. Creamware in the Royal style. D. 8".

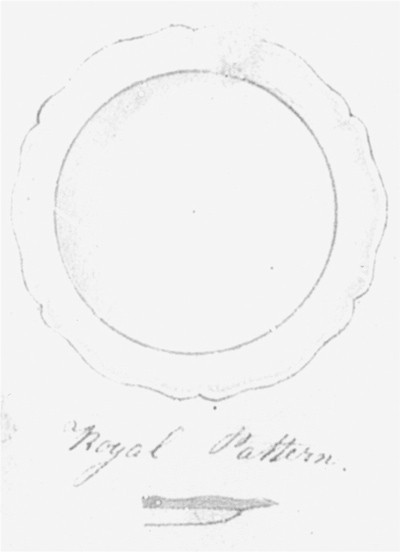

Royal Pattern creamware illustrated in Josiah Wedgwood’s 1802 trade catalog. (Courtesy, Birmingham Museum of Art.)

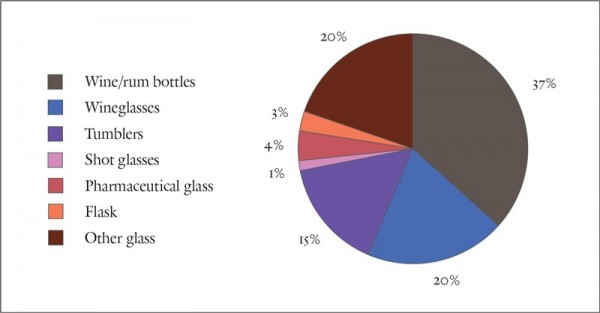

Types of glass vessels recovered from the Phillips trash pit.

Wineglass, shot glass, and punch cup. Possibly Germany, 1790–?, recovered from the Phillips trash pit. Leaded glass. H. of wineglass 5 1/2".

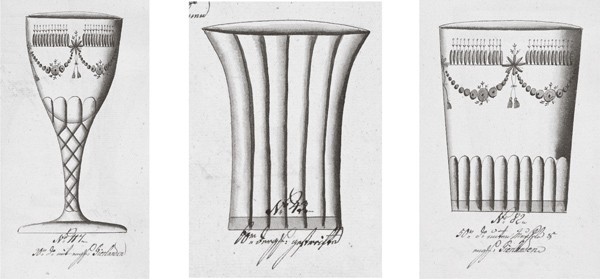

Glass forms illustrated in Johannes Schiefer, Pattern Book for Glass, ca. 1790–1825. (Courtesy, The Winterthur Library: Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.)

Wine bottles, France (far left) and England, 1780–1810, recovered from the Phillips trash pit. Blown glass. H. of tallest 13".

Storage jar, milk pan, and chamber pot, New England, 1800–1820, recovered from the Phillips trash pit. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. of milk pan 6".

Gin/mineral water bottle (left), Germany, 1750–1820; Westerwald-style storage jar (center), Germany, 1780–1820; Jug (right), Connecticut, 1800–1820, all recovered from the Phillips trash pit. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. of storage jar 14 1/4".

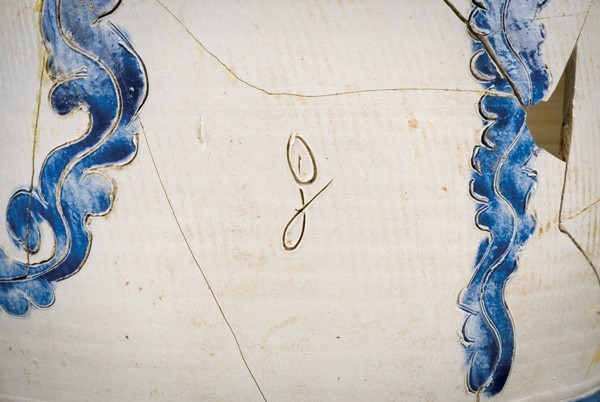

Detail of the inscribed mark on the body of the storage jar illustrated in fig. 32.

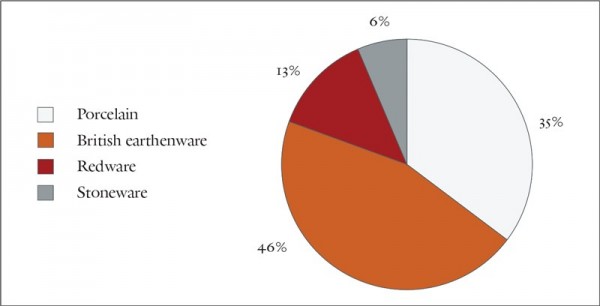

Ceramic types recovered from the Phillips trash pit.

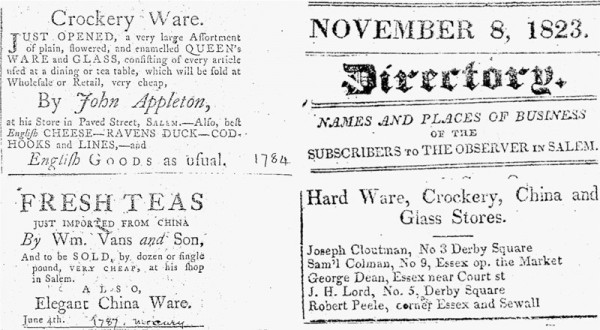

Advertisements and listings published in late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Salem newspapers.

In the fall of 1974, while archaeologists were excavating in Massachusetts at the Narbonne House on the property of the Salem Maritime National Historic Site, another dig was conducted on historic Chestnut Street in Salem.[1] Maritime artist Racket Shreve initiated repairs to the foundation of his studio barn attached to number 17, which was built in 1804–1805 for Captain Stephen Phillips, a successful sea captain and merchant during Salem’s golden age. While working around the foundation area, Shreve discovered fragments of Chinese porcelain sticking out of the ground near the southwest corner of the barn. A quick survey of the surface soil yielded many more pieces of high-quality ceramics. His curiosity piqued by these finds, Shreve halted his foundation work and over the next three summers diligently excavated what turned out to be a stone-walled trash pit measuring 6 feet by 5 feet (fig. 1). In the process, he uncovered a treasure trove.

In all, several thousand artifacts were unearthed, including a plethora of Chinese export wares: creamware, pearlware, redware, stoneware, and glassware. After mending a number of the artifacts, Shreve exhibited a few of them at the 1976 Salem Antiques Show at Hamilton Hall (also on Chestnut Street) and subsequently donated the collection to the Peabody Essex Museum. The only analysis of the collection conducted at the time was a four-page article in the show’s publication, which focused primarily on the physical attributes of the objects and the identification of certain wares without contextualizing them into the larger scope of Salem’s mercantile world.[2]

The archaeological history of Salem, one of the most important colonial and early American seaports, has a significant gap. Though work has taken place in the city since the late 1930s—including several undertakings at the Salem Maritime National Historic Site—no excavations of the dwellings owned by the prosperous merchant class during Salem’s golden age have been initiated.[3] Thus, the majority of what we know about Salem’s mercantile class and the goods they owned and used during this time comes from only a few contemporary sources, most notably shipping papers, diaries, and letters. The remainder of our knowledge has been based on the finest ceramics owned by merchant families (many in museum collections), historic homes that have been renovated throughout the years, and history books on Salem that were written nearly one hundred years after the city’s heyday, some of which are poorly documented and often loosely based on archival material. Fortunately, the collection of artifacts from the Phillips house now fills this niche for Salem archaeology and opens a window into the ceramic tastes of the mercantile class of the time.[4]

The artifact assemblage revolves primarily around Captain Stephen Phillips (1764–1838), whose life was an embodiment of Salem’s rise as a global port in America (fig. 2).[5] Phillips, who grew up during a tumultuous time in Revolutionary New England, spent his entire career aboard ships on the pioneering voyages to the Far East that helped Salem transition from a fishing port to an entrepôt (fig. 3).[6] At the end of the eighteenth century, several prominent merchants in Salem who wanted to retire to “a quieter and more pleasant place to live” than the crowded and noisy wharves on Derby Street relocated to Chestnut Street, an area between Essex and Broad Streets that was laid out in 1796.[7] Captain Phillips, now strictly a merchant shipowner and businessman, bought a portion of land in this recently developed area for himself, his second wife, Elizabeth, and his son, Stephen Clarendon, and had a three-story, hipped-roof house built in 1804–1805 (fig. 4).

The trash pit discovered by Racket Shreve was found under the foundation of a two-story, hipped-roof wooden barn attached to the west end of the house by a one-story shed that had been constructed between 1837 and 1851.[8] The pit was used primarily as a refuse dump for ceramics and miscellaneous items such as toothbrushes and pipes. The majority of the assemblage consists of nearly whole and a few intact vessels (fig. 5) and organic items, like animal and fishbones, which make up only a minuscule amount of the material deposited. These characteristics are typical of artifacts found in urban archaeological sites where rapid filling occurred, usually after the death of the head of the household or when the house changed hands or occupants, and often many ceramic and glass vessels can be almost fully reconstructed.[9]

Shreve pulled more than thirteen hundred artifacts from the trash pit, representing well over four hundred vessels (fig. 6). Most of the artifacts are ceramics and glass that date between 1790 and 1830. The forms are primarily ceramic plates, teabowls, and saucers (figs. 7, 8) as well as numerous fragments of wine bottles and Bohemian table glass. Most of them—the focus of this article—are Chinese export wares, pearlware, and creamware.[10]

Chinese Porcelain

Porcelain, the most expensive of all the ceramic types available to the American market in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, was not usually purchased by people of marginal wealth. It is not often recovered from North American archaeological sites that predate the 1730s, after which it became more popular and available.[11] Between 1780 and 1830, before the Industrial Revolution, Chinese blue-and-white porcelain was the most widely produced and exported item in the world.[12] As a result, Chinese porcelain is often present in the archaeological assemblages of upper-class households, particularly in the coastal areas of the United States.

One of the main reasons porcelain became immensely popular by the late eighteenth century was its elegant appearance, a strong contrast to the pewter and wood utensils more commonly used in the colonies. Chinese porcelain was particularly popular because it had become more durable than European earthenware and its Eastern origin and decorative motifs fascinated and pleased American buyers.[13] Once the American colonies achieved independence, Chinese export ware could be purchased directly from China, making it far more accessible.[14] Like their European counterparts, wealthier Americans often ordered pieces with patriotic or personal motifs such as flags and family crests.[15]

More than one-third of the ceramics uncovered in the Phillips trash pit (117 vessels) were Chinese export porcelain (fig. 9), which is remarkable given what has been found in other historic sites excavated in New England. Of the blue-and-white porcelain from the trash pit, 46 percent is what is commonly referred to as Canton ware. Nanking pieces account for 32 percent (fig. 10) and are almost exclusively in the form of teabowls and saucers (fig. 11).[16] These Nanking objects point to the continued importance of tea drinking in America after colonial times and suggest that more refined ceramics had become a requirement for this social practice among the merchant class.

In comparison to the finer Nanking porcelain, Canton ware was often marred by a variety of imperfections: the use of unrefined materials; the rigorous treatment of vessels during firing, which sometimes led to warping or “sooting”; and the overuse of glaze coating, which caused it to crawl, bubble, and become pitted under high kiln temperatures.[17] The combination of these factors often produced either a curdled “potato soup” or “orange peel” surface.[18] The relative poor quality of most Canton ware was understood by merchants. In 1815 the owners of the Salem brig New Hazard made it clear to master Benjamin Shreve that the porcelain was to be

smooth, the cups & saucers in particular not thick & clumsy. Let the patterns of the Enamelled Tea Sets, Cups & Saucers & Bowls be delicate, of lively patterns and shades. Those of a thick heavy daub will not bring so good prices by a good deal & cost as much. The blue & white Dining sets should be of uniform shade & same pattern. They are often put up without attention to these particulars.[19]

China trade historian Jean Mudge believes that the abundance of poor-quality Canton ware was a major factor in its low cost. Much of the Canton ware in the assemblage from the Phillips trash pit is coarse, pitted, and carelessly decorated and displays many imperfections (fig. 12).

While the vast majority of Chinese export porcelain found in the trash pit was underglaze blue-and-white ware, a few notable examples of overglaze pieces were uncovered as well. Fragments of at least three drum teapots were found as well as portions of a mid-eighteenth-century export plate (fig. 13). In addition, fragments from a Chinese porcelain dish decorated in the Japanese style with an overglaze application technique were recovered and date to about 1750–1765 (figs. 14, 15).[20] However, even though blue-and-white porcelain (whether Canton or Nanking) graced the tables of the most prominent citizens of America—George Washington, for example—the mere presence of porcelain in the assemblage should not be viewed as a definite indicator of high social status or extreme wealth. The trash pit contained a wide variety of porcelain and many low-quality pieces, and even though Captain Phillips was a successful ship captain and businessman, he was not in the tier of the wealthiest residents of Salem’s golden age—Elias Hasket Derby, for example, who was the first millionaire in America, or William Gray, worth $3 million at the time of the 1807 Embargo, and George Crowninshield Sr., worth an estimated $16 million.[21]

Pearlware

Pearlware from the Phillips trash pit comprises 22 percent of the ceramic assemblage, or 339 sherds (72 vessels). This rarely marked type is the kind most commonly found in early nineteenth-century archaeological sites in the eastern United States.[22] The majority of the pearlware found in the trash pit had been made in the early nineteenth century. Approximately one-third of it has molded shell-edged patterns with blue or green underglaze painting (fig. 16). Shell-edged motifs appear as early as 1775 on creamware and were probably one of the first used to decorate pearlware.[23] Pearlware continued to be manufactured in great quantities during the nineteenth century, although the occurrence of green painting diminishes toward the end of the pearlware period (figs. 17, 18).

Molded shell-edged decoration was used primarily on plates, as well as on larger serving pieces such as platters and tureens. When pearlware was first introduced, the acquisition of a full molded shell-edged dinner service was considerably more expensive than the acquisition of a set of plates. One serving piece cost as much as a dozen plates, and therefore a large dinner service required some expense to maintain. By the end of the pearlware period, however, shell-edged and other molded patterns were used only on platters and plates.

The largest proportion of pearlware found within the trash pit (45 percent) is transfer-printed. The development of transfer-printing designs under the glaze revolutionized the Staffordshire ceramic industry by creating uniform market vessels. The technique allowed potters to apply complex decorations quickly and relatively inexpensively, thus creating thousands of designs for ceramics in a variety of colors and styles that were in demand by consumers both in England and abroad.[24] Some of the most popular and well-known patterns of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were Blue Willow, Asiatic Pheasants, and Canova.

In the years following the Revolutionary War, Staffordshire potters found an enthusiastic market in America, and pottery in hundreds of patterns made the journey across the Atlantic Ocean to grace the tables of the new republic. George Miller and his colleagues have shown that in the 1790s printed wares cost three to five times more than undecorated cream-colored earthenwares but by the first quarter of the nineteenth century had dropped to one or two times. Printed wares began to appear in great numbers in America after the War of 1812, probably the result of a major fall in ceramic prices.[25] Nearly 43 percent of the plates and soup plates ordered by New York merchants between 1838 and 1840 were printed.[26]

Almost all of the transfer-printed pearlware uncovered from the trash pit has chinoiserie-style patterns. With the advent of underglaze transfer printing, production of the complex landscapes and geometric borders common on Chinese porcelains became more cost efficient.[27] In the mid-eighteenth century, consumers who desired expensive Chinese porcelains but were unable to afford them could instead turn to painted renditions of Chinese-style designs on less costly ceramics, in particular tin-glazed earthenwares.[28] The whiteness of the newly developed pearlware body and glaze was well suited to the traditionally blue Chinese motifs, and the combination of Chinese-style designs and vessel forms was designed to appeal to those who would otherwise purchase Chinese porcelain.[29]

There were also a few hand-painted examples of China glaze ware (fig. 19), a bluish tinted glazed earthenware with designs that imitated Chinese porcelain. It appears to have been first produced in 1775 in Staffordshire and was in use until the 1830s, although its peak production was between 1797 and 1814. China glaze ware resembles Chinese porcelain in its patterns, vessel shapes, blue-tinted glaze, and, of course, its name, “China glaze.”[30]

The Chinese-style printed wares recovered from the trash pit all relate to tea service—bowls, saucers (fig. 20), and one teapot—and in fact represent the only pearlware tea service found in the trash pit.

Chinoiserie designs were most commonly produced between 1816 and 1836, whereupon figures in Western dress and Western architectural features began to appear.[31] Common decorative motifs found on printed Chinese-style and chinoiserie earthenwares include pagodas, temples, weeping willow trees, cherry blossoms, orange trees, figures in Eastern dress, and junks and sampans.

One of the most interesting artifacts uncovered from the trash pit is a pearlware chamber pot with a medallion bearing a GR cipher for George III (fig. 21). English white salt-glaze washbasins and chamber pots were produced in large quantities until the 1760s, when imported German blue-and-gray stoneware began to infiltrate the American market.[32] In response to these new Westerwald wares, English salt-glaze potters created “scratch blue” chamber pots, mugs, and pitchers, which mimicked German-style wares.[33] The success of these English stoneware chamber pots led to the creation of pearlware copies; GR chamber pots, identical to the one from the Phillips trash pit, were made circa 1785–1810. Considering the intended contents of the vessel, the royal medallion was probably an expression of American patriotism, especially in light of the Revolutionary influence in Captain Phillips’s life.[34]

The large deposits of pearlware found in the trash pit suggest that even though Chinese porcelain was sought after for its fine qualities, physical appearance, and representation of an international perspective (or an expression of the exotic), English earthenware (with forms that mimic Chinese wares) actually fulfilled a significant portion of that demand. Americans continued to look to England as well as France for guidance in fashion and refined taste even after the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812.[35] The presence of fashionable items in one’s home, particularly those displaying scenes of faraway lands, conveyed messages about one’s place in the world and one’s knowledge of culture, history, and travel.[36]

Creamware

Ivor Noël Hume considers creamware to be “the most important development of the eighteenth century,” because it was “a gradual perfection of a thin, hard-firing, pale-yellow or cream-colored earthenware, which after a preliminary firing, could be dipped in a clear glaze.”[37] Seventeen percent of the ceramics recovered from the trash pit are creamware—209 sherds representing 55 vessels. Most of the uncovered forms (46 percent) are dinner plates, but also found were chamber pots, bowls, pitchers, basins, and a serving platter (fig. 22).

While various pattern books suggest that creamware plates were produced before 1783 with plain rims, they are generally found in American contexts of the 1790s and the early nineteenth century (figs. 23, 24). Although early creamware often has a deeper yellow color than later pieces (after 1785), this cannot be relied on for dating purposes: the trash pit yielded two plates decorated with the Royal Pattern (used as early as 1775) that had a light yellow glaze instead of the deeper yellow glaze commonly associated with the style (figs. 25, 26).

The majority of the recovered creamware hollow ware, apart from one annular punch or slop bowl, is utilitarian and undecorated. Among these items are three chamber pots, which were constructed with simple, plain bulbous bodies, flat angular rims, and handles anchored at the top of the body just under the rim.[38] These pots are commonly associated with the last quarter of the eighteenth century, after which they were replaced by pearlware forms. The purely functional nature of the creamware vessel forms found in the trash pit reflects the decline of the ware’s status in nineteenth-century America.

Glass

Perhaps the most intriguing find on the site is the fancy decorative glass found among the 133 sherds (71 vessels) of glass.[39] This glassware accounts for 20 percent of the glass discovered (fig. 27). There are seven identical chip-cut stemmed wineglasses with swagged and tasseled borders, three of which are almost complete vessels with bases. In the same style are a few straight-sided and barrel-shaped tumblers and one punch cup with a handle (fig. 28). This assemblage of decorative glassware is similar to patterns from a 1794 illustrated trade catalog of Bohemian glass distributor Johannes Schiefer (fig. 29), who operated an export and commission agency for trade to America, Russia, Spain, and other countries.[40] The catalog and price list were found among the possessions of John Gardiner of Gardiners Island, New York, but the catalog did not give manufacturer names.

Vast amounts of glassware decorated with delicate engraving and facet cutting were imported from Europe to the United States after the Revolution. Most of it is recorded as “German,” since it was made in glasshouses in Bohemia and other German states.[41] One might assume that this fine-quality glassware was quite costly, but in fact Bohemian glassware—made using a lightweight, nonleaded glass—was less expensive than English and Irish wares done in the same style. In 1813 a Philadelphia glass-and-china merchant shop advertised cut and engraved English wineglasses at $3.50 per dozen, whereas identical German models were only $2.00 per dozen.[42] The presence of such large numbers of Bohemian glass in the trash pit, as compared with English examples, suggests that Americans bypassed British wares in favor of the equally stylish yet significantly cheaper German glassware.

Most of the bottles found on New England historical sites are British-made dark green glass “wine” bottles, as were, but for one French bottle, those found in the Phillips trash pit. These vessels, similar to dated examples from the last quarter of the eighteenth century to the early nineteenth century, were used for shipping, storing, maturing, and serving a variety of liquids, such as ale, cider, distilled liquor, and wines (fig. 30).[43]

The large quantity of wine/rum bottles discovered in the Phillips trash pit (37 percent of the glass found) is in line with what is known about the popularity of liquor in Salem during its golden age. Small beer had been manufactured locally as early as 1637, and rum distilleries were established beginning with Emanuel Downing in 1648. By 1773 there were fifteen retailers in Salem selling spirits—St. Croix rum, Madeira wine, cherry brandy, and many other alcoholic beverages. The archaeological record and newspaper documentation reflect the role strong drinks played in daily food consumption. According to an address to the Essex County Prohibition Club in 1890 by historian Sidney Perley, “drunkenness was as common in the eighteenth as it had been in the seventeenth century. . . . After the revolution the production of liquor had greatly increased, and intemperance was more prevalent than ever.”[44] Although it is known that Perley favored prohibition and might have been prone to exaggeration, the presence of twenty-six wine/rum bottles in the Phillips trash pit is certainly good evidence for his claims.

Coarse Earthenware

Thirteen percent of the ceramics found in the Phillips trash pit were coarse earthenware vessels—106 sherds (40 vessels). These locally made vessels are abundant on many seventeenth-and eighteenth-century sites in New England, often accounting for more than 85 percent of the total ceramic assemblage.[45] Approximately 175 potters lived and worked in Massachusetts between 1650 and 1798, since “the excellence and abundance of clay, the proximity of home markets, and the ready means for shipping the wares encouraged many craftsmen to enter the trade.”[46] At the Salem Village Parsonage site (1681–1784) in Danvers, wheel-thrown plain earthenwares make up 89.6 percent of the total ceramic assemblage.[47] The majority of domestically produced redware found in colonial assemblages represents a relatively inexpensive commodity due to the ease in producing these wares and their frequent and hard use for dairy, kitchen, and food preparation.[48]

The potting industry reached its peak between 1775 and 1800. In 1775 seventy-five potteries operated in Danvers and Peabody, but by 1798 there were only twenty.[49] This decline in redware production, illustrated in the ceramic assemblage of the Phillips trash pit as well, is a direct result of several factors. The flood of European and Chinese ceramics into Salem forced the remaining redware potters to streamline their industry and abandon the manufacture of tablewares. Moreover, potters in eighteenth-century Massachusetts did not have large quantities of the raw materials—fine kaolin clays, for example—needed to produce the buff-bodied wares that had become popular, nor did they have “the sociopolitical organization, the economic resources, nor the authority for . . . importation.”[50] After the War of 1812, approximately thirty earthenware potters remained in South Danvers, attesting to the lessening demand for these wares in comparison with refined English earthenwares.[51]

In 1810 Tench Coxe, a proponent of American-based potteries, noted, “the manufactory of ordinary ware of common potters’ clay is very much extended in the United States. It is of great use in dairies, kitchens, larders, store-rooms, sale stores and manufactories.”[52] Coxe’s statement is supported by the archaeological assemblage from the trash pit, since the redware forms (except for three Buckley ware pitchers) are strictly utilitarian, used for storage, dairy production, and chamber pots (fig. 31).

Utilitarian Stoneware

For much of the eighteenth century British brown stonewares and German Westerwald blue-and-gray jugs, cylindrical tankards, and chamber pots were exported in very large quantities to America. Compared with other types recovered from the trash pit, the number of utilitarian stoneware vessels found (56 sherds, 26 vessels) is quite small, accounting for only 6 percent of the ceramics (fig. 32), and most is in the form of gin or mineral water bottles (fig. 32, left).

Double-handled storage jars, made with horizontal rolled handles that were decorated with cobalt and stamped floral devices, were exported in small quantities to the American colonies in the second and third quarters of the eighteenth century. The most intact piece of stoneware recovered from the trash pit is an example, with handles, incised blue decoration, and a salt glaze (figs. 32 [center], 33). At first glance the somewhat crude execution of the jar made it a candidate for an American example made in kilns in Manhattan or New Jersey.[53] While the vessel shares many characteristics with early American examples, the presence of shallow chatter marks—regularly spaced cordations in the surface of the clay resulting from the use of a template blade during the forming of the pot—has been seen only on Westerwald products.[54] Regardless of its German origin, this type of Westerwald is rarely seen in American archaeological contexts.

Discussion

The plethora and variety of ceramics and glass found in the Phillips trash pit are not surprising in the context of Salem during its golden age, a period in which increased global mercantile activity brought many worldly goods to the city. From 1785 to 1807, 1,500 crates of Chinese porcelain were imported into Salem (with one-half then transported to other ports); 1,364 crates of European earthenware (84 percent of it creamware and pearlware) were imported into both Salem and Marblehead.[55] This ratio, very similar to that of the porcelain as compared with the creamware and pearlware in the Phillips trash pit, is a good example of archaeology reflecting history (fig. 34). It shows how vast the ceramic market of Salem was, a direct effect of Salem’s establishment as a cosmopolitan city after the Revolutionary War. For this reason we find a multitude of porcelain, pearlware, creamware, other ceramic types, and glassware in the inventories of homes, the probate records of merchants, and now, for the first time, in the archaeological assemblage of a trash pit found on the property of a successful Salem merchant.

This picture becomes clearer in an examination of the numerous local advertisements published in Salem papers from the 1780s to the 1830s (fig. 35), which shows that Salem residents had access to a wide array of ceramics and glassware. In 1784 one merchant advertised in the Salem Register “a very large Assortment of plain, flowered, and enamelled QUEEN’S WARE and GLASS, consisting of every article used at a dining or tea table, which will be sold at Wholesale or Retail, very cheap, By John Appleton, at his Store. . . .” On June 4, 1787, about one year after the return of the Grand Turk, the first Salem ship to sail to China, William Vans and Son advertised “fresh” China teas for sale and “Elegant China Ware.” Even in 1823, by which time the port of Salem had started to decline as a center of overseas trade, the Observer’s published directory of the names and businesses of its subscribers included numerous “Hard Ware, Crockery, China and Glass Stores.”

Tea drinking became normative behavior in America after the 1750s, by which time one-third of the population “at a moderate consumption, [drank] tea twice a day.”[56] A by-product of increased mercantilism and the controlled manners of the merchant elite, tea consumption was closely tied to the ceramic trade. With this in mind, it is not surprising to find large numbers of teabowls, saucers, and teapots in the Phillips trash pit. According to archaeologist Lorinda Goodwin, tea services became a required necessity in connection with the social act of drinking, and the presence of multiple services in the Phillips trash pit suggests that the family entertained a larger social circle of friends and business partners.[57] Although most of the teaware from the trash pit is Chinese porcelain, there is a fair amount of pearlware, indicating that although Chinese porcelain was considered the most elegant—and therefore preferred—service for tea, a family of some significant social status relied on earthenware equivalents as acceptable substitutes.

Conclusion

Jonathan Goldstein, an economic historian who wrote about the Philadelphia China trade, argued that porcelain was “the single largest traditional Chinese decorative item which the average American could afford.”[58] From the data already discussed—its prevalence in the Salem market, the relatively inexpensive price for blue-and-white ware, and its presence in the trash pit of a merchant family—the statement appears to be accurate. After the Revolution, Salem merchants imported more porcelain than they re-exported, pointing to an increase in consumption by local residents.[59] While the elite Salemites owned many porcelain items, it is not unreasonable to think working- or lower-middle-class families might have owned a set or two of tea service. Archaeological evidence of their homes during Salem’s golden age is required to confirm this claim.

The Phillips family’s story represents a micro-historical study of Salem during its golden age. What began as one man’s curiosity has produced a significant contribution to Salem’s archaeological record, filling a major hole in the archaeological excavations of households that have been undertaken to date. The collection of artifacts from the Captain Stephen Phillips house is important for reassessing Salem’s past and offers a baseline for future archaeological and historical endeavors. It also provides an indication of the taste preferences of Salem residents, specifically the merchant class. Like Captain Phillips, Salem was a “go straight ahead”[60] city after the Revolutionary War. The city’s merchant class created global trading networks on their own, establishing direct routes between Salem and the Far East. These lines of exchange brought significant wealth to the city, making it the sixth largest port in America by 1790, and allowed its citizens access to worldly goods. As a result, a larger percentage of Salem residents were able to live a cosmopolitan lifestyle, having access to spices for meals, being able to have tea in Chinese porcelain and English services, and drinking spirits from glassware made in distant lands. The archaeological record tells this story through a Salem sea captain who rose through the ranks to become a successful merchant, who participated in the importation of foreign goods by captaining some of the first ships to venture into Far Eastern ports, and who was a central participant in the city’s flourishing economy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project would not have a life had local artist Racket Shreve not discovered the artifacts at his home on Chestnut Street in the mid-1970s. He provided immense enthusiasm, support, and interest in my work. I would like to thank the many staff members at the Peabody Essex Museum for their help along the way: Dr. Daniel Finamore, Russell W. Knight Curator of Maritime Art and History, for directing me to the collection of artifacts from 17 Chestnut Street and for his editorial comments; William Sargent and Karina Corrigan, H. A. Crosby Forbes Curator of Asian Export Art, for their help in the identification of Chinese export porcelain; and Dr. Jeffrey P. Brain, for his help in analyzing stoneware and glass material from the trash pit. I am grateful for the background on several members of the Phillips family provided by Margherita Desy, historian at the Naval History & Heritage Command Detachment in Boston, and for the archaeological insight of Professors Stephen Mrozowski, Stephen Silliman, and David Landon of the University of Massachusetts, Boston. I thank Rob Hunter for his continued interest in this piece.

Geoffrey P. Moran, Edward F. Zimmer, and Anne E. Yentsch, Archaeological Investigations at the Narbonne House: Salem Maritime National Historic Site, Massachusetts, Cultural Resources Management Study No. 6 (Boston: National Park Service, 1982).

Roger D. Howlett, “In Praise of Trash,” in Hamilton Hall Antiques Show (Salem, Mass.: Peabody Museum of Salem, 1975).

Salem’s golden age is considered to be a period following the Revolutionary War to about the 1820s, when Salem ships were trading directly with the Far East.

Since a trained archaeologist did not oversee the excavation, stratigraphy was not recorded, nor were soil changes and levels noted. Without these forms of data, no depositional matrix could be constructed, and artifacts from different depositional layers could not be discerned as homogeneous or not. The loss of these methods to place the artifacts in specific contexts is disappointing but did not significantly detract from the overall analysis of the site. The artifacts were still contextualized within a structure that was used specifically for dumping refuse items, which to some degree offsets the lack of stratigraphic data.

George Schwartz, “‘Go Straight Ahead’: Salem’s Rise to Global Entrepôt as Reflected in the Archaeological Assemblage from the Captain Stephen Phillips House” (master’s thesis, University of Massachusetts, Boston, 2005).

His father, Deacon Stephen Phillips, was an integral part of the growing patriotic movement throughout Marblehead. In 1770 he was voted moderator of the town meeting, one of the most powerful and influential political positions in the town and one he held throughout most of the Revolutionary period. Leading meetings at which many patriotic measures foreshadowing the coming revolution were passed or discussed, he was able to steer local legislation and appoint committees. It is against this backdrop of revolution that Captain Stephen Phillips was educated. For more on the life of Captain Phillips, see ibid., pp. 21–33.

Richard Hall Wiswall, “Notes on the Building of Chestnut Street,” Essex Institute Historical Collections 75 (1939): 206.

The construction of the barn sealed off the trash pit.

Stephen A. Mrozowski, “Prospects and Perspectives on an Archaeology of the Household,” Man in the Northeast 27 (1984): 41.

Minimal amounts of earlier tin-glaze wares and later whitewares were found in the trash pit.

Ivor Noël Hume, A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1969), p. 256.

H. A. Crosby Forbes, Hills and Streams: Landscape Decoration on Chinese Export Blue and White Porcelain, exh. cat. (Washington, D.C.: International Exhibitions Foundation, 1982), p. 6.

Jean McClure Mudge, Chinese Export Porcelain for the American Trade, 1785–1835 (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1962), p. 70.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Five Fitzhugh pattern plates were also in the trash pit.

Ibid., p. 71.

Variation in the quality of Canton ware is not a direct correlation to the time in which it was produced. It is often said, however, that after the first quarter of the nineteenth century the quality of Canton deteriorated.

Quoted in Mudge, Chinese Export Porcelain for the American Trade, p. 75.

Personal communication with William Sargent.

Salem: Maritime Salem in the Age of Sail, National Park Service Handbook 126 (Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, 1987).

Lynne Sussman, “Changes in Pearlware Dinnerware, 1780–1830,” Historical Archaeology 11 (1977): 111.

Ibid., p. 107. George L. Miller and Robert R. Hunter Jr., “English Shell-Edged Earthenware: Alias Leeds Ware, Alias Feather Edge,” in The Consumer Revolution in 18th-Century English Pottery, Proceedings of the Wedgwood International Seminar, no. 35 (n.p.: Wedgwood International Seminar, 1990), pp. 107–36; and Robert H. Hunter Jr. and George L. Miller, “English Shell-Edged Earthenware,” The Magazine Antiques 145 (March 1994): 432–43.

Patricia M. Samford, “Response to a Market: Dating English Underglaze Transfer-Printed Wares,” Historical Archaeology 31, no. 2 (1997): 1.

George L. Miller, Ann Smart Martin, and Nancy S. Dickinson, “Changing Consumption Patterns: English Ceramics and the American Market from 1770 to 1840,” in Everyday Life in the Early Republic, edited by Catherine E. Hutchins (Winterthur, Del.: Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, 1994), pp. 234–38.

Ibid., p. 234.

Samford, “Response to a Market,” p. 3.

Miller, Martin, and Dickinson, “Changing Consumption Patterns,” p. 234.

Samford, “Response to a Market,” p. 8.

George L. Miller and Robert R. Hunter, “How Creamware Got the Blues: The Origins of China Glaze and Pearlware,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 135–61.

Only a few of the sherds recovered had these types of designs. Samford, “Response to a Market,” p. 1.

Hume, Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America, p. 118.

Ibid.

James Duncan Phillips, “Captain Stephen Phillips, 1764–1838,” Essex Institute Historical Collections 76 (1940): 97–135. It is against this backdrop of revolution that Captain Stephen Phillips was educated. His adolescence was heavily influenced by the continual warfare he witnessed in the North Shore beginning at the age of eleven. At this point in his life, Colonel Leslie’s regiment had landed in Marblehead for a raid on Salem. Family legend has it that young Stephen, at the age of thirteen, offered his services to John Paul Jones for the Ranger’s voyage to France in October 1777. Phillips was turned away at the last moment because he was considered too young, an experience that he recounted later in his life to his grandson Stephen Henry Phillips as “a great disappointment in my life.”

Samford, “Response to a Market,” p. 7.

Ibid.

Hume, Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America, p. 123.

Ibid., p. 148.

Examples of less expensive glasses of about the same period, blown but uncut and undecorated, include two straight-sided tumblers and the shot or cordial glass with blown paneled sides.

Arlene M. Palmer, Glass in Early America: Selections from the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum (Winterthur, Del.: Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, 1993), p. 72.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Olive R. Jones, Cylindrical English Wine and Beer Bottles, 1735–1850 (Ottawa, Ont.: National Historic Parks and Sites Branch, 1986), p. 17.

An address delivered by Sidney Perley at the quarterly meeting of the Essex County Prohibition Club at Topsfield, April 16, 1890, published in the Salem Gazette, April 22, 1890.

Sarah Peabody Turnbaugh, “17th and 18th Century Lead-Glazed Redwares in the Massachusetts Bay Colony,” Historical Archaeology 17, no. 1 (1983): 3.

Ibid., pp. 4, 13.

Ibid., p. 3.

Ibid., p. 4.

Jessica Lanier, “The Post-Revolutionary Ceramics Trade in Salem, Massachusetts, 1783–1812” (master’s thesis, Bard Graduate Center, New York, 2004), p. 191.

Turnbaugh, “17th and 18th Century Lead-Glazed Redwares in the Massachusetts Bay Colony,” p. 14.

Lanier, “Post-Revolutionary Ceramics Trade in Salem,” p. 203.

Quoted in ibid., p. 202.

Arthur F. Goldberg, Peter Warwick, and Leslie Warwick, “The Eighteenth-Century New Jersey Stoneware of Captain James Morgan and the Kemple Family,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Easthampton, Mass.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2008), pp. 2–40; and Meta F. Janowitz, “New York City Stonewares from the African Burial Ground,” in ibid., pp. 41–66.

Ivor Noël Hume, If These Pots Could Talk: Collecting 2,000 Years of British Household Pottery (Milwaukee, Wis.: Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 106–7.

Lanier, “Post-Revolutionary Ceramics Trade in Salem,” p. 177.

Lorinda B. R. Goodwin, An Archaeology of Manners: The Polite World of the Merchant Elite of Colonial Massachusetts (New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 1999), p. 31.

Ibid., p. 123.

Jonathan Goldstein, Philadelphia and the China Trade, 1682–1846: Commercial, Cultural, and Attitudinal Effects (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1978), pp. 38–39.

Lanier, “Post-Revolutionary Ceramics Trade in Salem,” p. 212.

The expression “go straight ahead” was used by Captain Phillips to describe a progressive person who is continually moving forward, striving for better things for himself and the society in which he lives while not being held down by the mentalities and biases of the past. The captain’s son, Stephen Clarendon, refers to his father’s maxim in a letter to his own son Stephen Henry a few days after the captain’s death in 1838; Phillips House collection, Salem, Massachusetts.