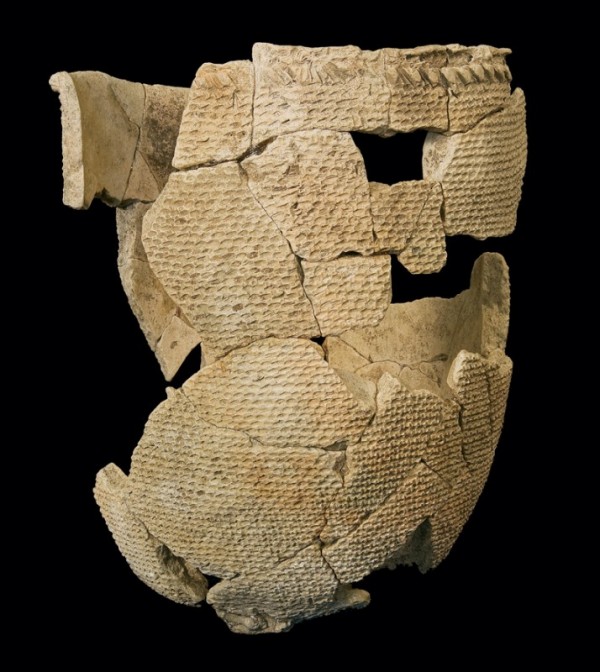

Basket pot, attributed to Robert Cotton, Jamestown, Virginia, 1608–1611. Unglazed earthenware. H. 10". (Courtesy, Preservation Virginia; photo, Michael D. Lavin.)

(Left) Modeling clay impression of the rim of the basket pot illustrated in fig. 1 alongside (right) the actual rim sherd, showing the pattern of twined fiber.

Many of the European elite in the early modern period enjoyed assembling collections of natural and artificial oddities from around the world. Natural history specimens, including live animals, were collected along with precious man-made objects and displayed in house zoos and in Wunderkammern, or cabinets of curiosity. These collections conveyed to others their owners’ knowledge, status, and refinement. They were also reflective of political and mercantile interests and exemplified the “need to control human and natural resources in the New World, and . . . the search for things that could bring profits to the Old World.”[1]

In 1608 newly arrived Jamestown colonist Francis Perkins sent to friends in England some exotic New World gifts, among them four pairs of turtledoves, two Indian-made “pots of our ordinary earth,” a corncob (“ear of the native wheat”), and twelve pounds of sassafras “to use in medicines or between linens.” Perkins promised to send “better things” on the next ship, including some little animals “with skins of fine fur” if he were able to acquire any.[2] King James I of England was eager to acquire some of the Virginia flying squirrels he had heard about, and London antiquarian Sir Walter Cope’s cabinet of curiosities is documented as having contained many New World objects, including an Indian canoe and “flies that glow at night in Virginia.”[3]

In seventeenth-century Virginia, the culture of collecting was practiced not only by the English but also by the Native Americans, who were eager to acquire the exotic objects—copper, iron tools, glass mirrors, and beads—the colonists offered in exchange for food. Just as the Virginia Company of London attempted to gain control of Virginia’s resources, paramount chief Powhatan of the Powhatan tribe tried to command access to the English artifacts that were used as tribute goods in his stratified society. On one occasion, for instance, he was led to believe by the English that certain blue glass beads were “composed of a most rare substance of the coulour of the skyes, and not to be worne but by the greatest kings in the world.” According to Captain John Smith, this made Powhatan “halfe madde to be the owner of such strange Jewells.”[4]

The Jamestown colonists, preoccupied with trying to locate or produce commodities of value for the London investors, were largely dependent on the Indians for food. Corn, which made up a large percentage of the native diet, was the most common foodstuff obtained through trade, and it was purchased from the Indians by the basketful.[5] The baskets, made by the native women of cornhusks, tree bark, grass, and other fibers, did not have a rigid framework but were flexible containers. This is indicated in a 1609 trading encounter when, after the English had worked out the quantity of “copper and beads and other things” to exchange for corn, they discovered that the Indian warriors were craftily pushing up the bottoms of their baskets with their hands “so that the less corn might fill them.”[6]

One of these Indian baskets, probably acquired through trade with the Powhatan, was used by an English colonist to form a pit-fired clay pot that was found by archaeologists in a circa 1610 context within James Fort (fig. 1). Robert Cotton, who arrived at Jamestown in April 1608, is believed to be the source of the pot for several reasons. He was a tobacco pipe maker whose Virginia-clay pipes are numerous in the fort’s earliest contexts, he is considered the only colonist working with clay at this early date, and the pot’s clay matrix appears identical to that of his pipes.[7]

The pot had been shaped by pressing layers of clay into the basket’s interior, resulting in walls nearly 3/4-inch thick. Cotton then fired the clay pot over low heat, which burned off the basket material while leaving its impressions on the pot’s exterior. The basket’s fibers produced a clean imprint in the clay with no fibrous offshoots, leading basket maker and historical interpreter Sharon Walls to conjecture that the fibers were produced from the leaves of Yucca filamentosa, a native plant used by the Virginia Indians for its durability and strength.[8]

The pot was produced to function as a traditional English form, as evidenced by the addition of clay pads on its base to enable the vessel to sit upright, unlike the native pots, which had a cone-shaped base and were propped in the hearth using wood and stone cobbles. As the modeling clay impression of the vessel shows clearly (fig. 2), the basket used for the mold was a flexible container made of finely woven twined fiber. In twining, the wefts are worked in pairs, one going over the warp and the other under; as the wefts are woven, they are twisted, producing a distinctive diagonal pattern. The rim of the basket was finished off by pulling two warps from the left over one from the right and then braiding the fibers together.

Cotton’s “basket pot” could represent a quick and easy solution for producing a needed clay pot, but it could also reflect an Englishman’s appreciation for Powhatan basketry and his attempts to preserve it. Either way, the unique pot provides us with a rare opportunity to examine the fiber artistry of a native Virginia woman from four hundred years ago, as she fashioned a functional object from the natural world.

Beverly A. Straube, FSA, Senior Archaeological Curator, Jamestown Rediscovery Project, Historic Jamestowne, bly@preservationvirginia.org

Antonio Barrera, “Local Herbs, Global Medicines: Commerce, Knowledge and Commodities in Spanish America,” in Merchants and Marvels: Commerce, Science, and Art in Early Modern Europe, edited by Pamela H. Smith and Paula Findlen (New York: Routledge, 2002), p. 165.

A New World plant, sassafras was particularly valued in Europe as a treatment for syphilis. Philip L. Barbour, ed., The Jamestown Voyages under the First Charter, 1606–1609, 2 vols. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press for the Hakluyt Society, 1969), 1:161.

Ibid., 2:288. Cope’s objects were noted in 1599 and probably were acquired from Sir Walter Raleigh’s 1585–1587 colonizing attempts in modern-day North Carolina. See Thomas Platter, Thomas Platter’s Travels in England, 1599, translated by Clare Williams (London: J. Cape, 1937), pp. 172–73.

Philip L. Barbour, ed., The Complete Works of Captain John Smith (1680–1631), 3 vols. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1986), 2:156.

Historian Kathleen M. Brown has estimated that corn provided about 75 percent of the calories consumed by the Indians living in the Coastal Plain. See Brown, Good Wives, Nasty Wenches, and Anxious Patriarchs: Gender, Race, and Power in Colonial Virginia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1996), p. 46.

Edward Wright Haile, ed., Jamestown Narratives: Eyewitness Accounts of the Virginia Colony, the First Decade, 1607–1617 (Champlain, Va.: RoundHouse, 1998), p. 484.

William M. Kelso and Beverly A. Straube, Jamestown Rediscovery, 1994–2004 (Richmond, Va.: Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, 2004), pp. 163–66.

Sharon Walls, personal communication, 2006.