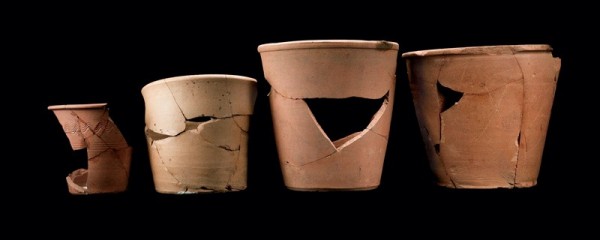

Flowerpots, probably American, ca. late 1830s–early 1840s. Unglazed earthenware. H. of tallest 7". (Photos, Melody Henkel.) The pot on the far left is decorated; the one on the far right is incised.

Flowerpot, probably American, ca. late 1830s–early 1840s. Unglazed earthenware. H. 10 3/16". The decoration on this vessel is the most common type on the decorated sherds in the collection.

Flowerpot fragment, probably American, ca. late 1830s–early 1840s. Unglazed earthenware. H. 1 5/8". This is the sole example of slip decoration in the collection.

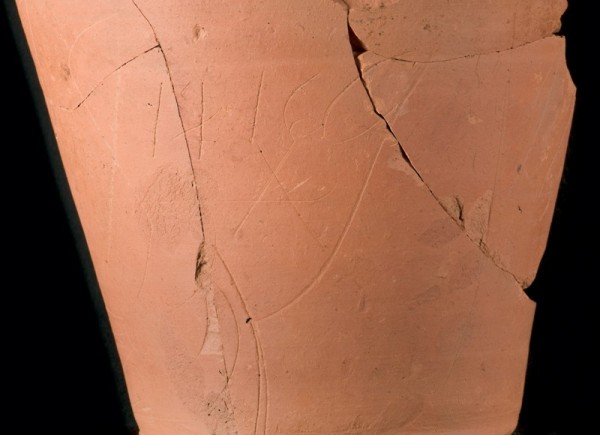

Detail of the scratches on the side of the flowerpot illustrated at the far right in fig. 1. Another pot (not shown) is marked with a scratched “X.” The meaning of these scratches is not clear, but they may have recorded information about the plant, as gardening manuals advised.

Excavations at an early-nineteenth-century greenhouse at Gore Place in Waltham, Massachusetts, yielded 2,083 terracotta planting pot sherds, a common yet little studied artifact type.[1] Gore Place was one of a number of federal-period country seats in the greater Boston area, home to Christopher Gore, a Massachusetts governor and United States senator, and his wife, Rebecca. A politician by profession, Gore invested a great amount of energy in his farm, as did many of his peers. Many federalist merchants and political leaders owned country properties and joined the Massachusetts Society for Promoting Agriculture (MSPA), an elite organization whose members were interested in scientific agriculture, such as attempting to improve crop yields through selective propagation or soil enrichment or importing new livestock and plant breeds.[2]

Excavations in 2008 by the Fiske Center for Archaeological Research at the University of Massachusetts, Boston uncovered some of the remains of the Gores’ 1806 greenhouse, including the planting pot fragments. Keeping potted plants in greenhouses allowed residents of colder climates to grow species that were “rare, foreign, and tender.”[3] In Massachusetts, this allowed people to cultivate exotic flowers and citrus trees.[4] The Gores’ greenhouse seems to have been a relatively lavish structure designed to be seen by visitors; it was located along the entrance drive to the property, and excavations recovered fragments of marble floor tile, suggesting that the interior was a well-finished space. The greenhouse stood until at least 1841, but seems to have fallen out of use during the late 1830s or early 1840s during the period when Theodore Lyman Jr. owned the property (1834–1838) or during the occupation of John Singleton Copley Greene (1838–1856).

Description of the Collection

All of the planting pots from Gore Place are unglazed earthenware, reddish yellow or yellowish red, with no inclusions visible to the naked eye. At least 149 pots are represented, ranging in diameter from about 13/16" to 11 13/16".

There are six basic rim profiles with significant variation within each one (fig. 1). Twelve of the identified pots are decorated, eleven with non-identical tooled or engine-turned bands of straight and/or wavy lines (fig. 2) and one with texturing seemingly created by sponging the exterior.

Additional body sherds are also decorated, most with similar tooled patterns, although one is painted with white and black slip (fig. 3). Another bears letters, numbers, and symbols scratched onto the exterior, presumably during its use-life (fig. 4).

Fifty-nine distinct bases were identified, and of the thirty-two that extend to the center all have a central drainage hole, mostly about 13/16" in diameter but ranging from about 3/16" to 1 5/8". No drainage holes on the lower body were found as is sometimes seen on other flowerpots from this period.

Like the eighteenth-century planting pots found at Mount Vernon in Virginia, these do not have footrings.[5] No terracotta saucers, or plant trays, were found. Sherds found in the debris suggest refined earthenware plates may have served this purpose, although some contemporary authors advised against using saucers in the greenhouse because they inhibited drainage and held stagnant water.[6]

Manufacture

All of the pots from Gore Place were wheel thrown, as they predate the 1861 invention of the flowerpot molding machine by William Linton, and thus display individual variations in rim profile, decoration, and diameter. The similarity of the decoration on the eleven tool-decorated pots suggests that they all came from one workshop, but the manufacturer has not been identified. Other scholars have noted the longevity of the general flowerpot form and the difficulty of dating or sourcing individual examples.[7] It is assumed that, like other utilitarian earthenware, flowerpots were acquired from one of the region’s local potters before the industrialization of the flowerpot industry after 1861; they were occasionally imported from overseas, however, as indicated in an advertisement in a Quebec newspaper for flowerpots from England.[8]

Identifying the source for Gore’s pots would be very difficult without some mention in his personal papers. Early-nineteenth-century potters did not necessarily specialize in flowerpots. Hervey Brooks of Goshen, Connecticut, for example, was a farmer-potter who produced assorted utilitarian earthenwares between 1795 and 1867; flowerpots are mentioned only in some of his later lists of wares. John Worrell’s study of Brooks’s immediate neighborhood identified seven individuals who occasionally made and sold pottery between 1790 and 1810, only two of whom had been previously identified by scholars and none of whom was identified in period sources as primarily a potter.[9]

Other eastern Massachusetts potters known to have produced planting pots during this period include Benjamin Ingalls of Taunton, Stephen Bradford of Kingston, several generations of the Hews family of Weston and North Cambridge, and John Runey of Charlestown.[10] Of these, the Hews company is the best documented, since it continued into the mid-twentieth century. Flowerpots became the company’s primary product but were mentioned in the company records as early as 1807. Examination of pots attributed to Hews that are owned by the Weston Historical Society, however, did not detect any diagnostic similarities between those and the pots from Gore Place.[11] Receipts indicate that John Runey sold pots to the MSPA’s Botanic Garden, and Gore, as a founding member of the MSPA and visitor to the Botanic Garden, may have been aware of Runey as a source; however, no attributed Runey pots are known to the authors.[12]

Intensive Horticultural Practices

Pot sizes were variously described by contemporary sources by the cost of the pot, the number of pots of the size made from a set amount of clay, or by rim diameter. Several nineteenth-century gardening treatises attempted to create a standard terminology to describe pot sizes, but none seemed to gain widespread acceptance.[13]

Most of the pots in the Gore Place collection were between roughly 3 7/8" to 8 13/16" in rim diameter, with the largest concentration between about 4 5/16" to 6 5/16". Nineteenth-century gardening manuals recommended constant repotting into gradually, incrementally larger pots as a process integral to plant health, so having a range of mid-size pots was important. The range of pot sizes on hand in the greenhouse, therefore, speaks not only to the owner’s initial investment in purchasing the plants but to the continued investment in their care and display. Caring for greenhouse plants involved specialized labor, professional English gardeners, and, in the Gores’ case, construction and maintenance of the greenhouse as well as upkeep of the plants by watering, applying pesticides, removing dead leaves, and repotting.

The smallest and largest of the pots speak to the level of intensity and specialization of the horticultural enterprise at Gore Place. The smallest ones, called “thumb” or “thimble” pots, include two pots with rim diameters of about 13/16" or 1 5/8" and seven bases 2" in diameter. These small pots were used for propagating plants from seeds or clippings and indicate that their owners were not only purchasing mature plants but raising new ones, a more intensive activity. C. M. Hovey, who tried to institute a standard numeric system for pot sizes, did not include thumb pots (“little use is made of [them], except by propagators”) nor pots greater than 9" in diameter, which he called “Extras,” as “[t]hey are scarcely ever made by the manufacturers, unless expressly ordered by persons who desire such for particular purposes.”[14] The Gore Place collection includes six pots with rim diameters of 10" or larger, again suggesting large pots that could be used for shrubs or potted fruit trees.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank the Gore Place Society for its support. Gore Place is undertaking a major research effort to understand the agricultural and horticultural activities that have taken place on its property, of which archaeology is just one part.

Christa M. Beranek and Rita A. DeForest, Fiske Center for Archaeological Research, University of Massachusetts, Boston

christa.beranek@umb.edu, radefor@verizon.net

Other archaeological studies of planting pots include Geneviève Duguay, “Utensils for the Growing of Plants,” in Under the Boardwalk in Québec City: Archaeology in the Courtyard and Gardens of the Château Saint-Louis, edited by Pierre R. Beaudet (Montreal, Quebec: Guernica; Sillery, Quebec: Septentrion, 1990), pp. 109–21; James Goodwin and Eleanor Breen, “Flowerpots of Mount Vernon’s Upper Garden: 44FX762/43,” unpublished report, Mount Vernon Archaeology Department, 2005 (available online at www.mountvernon.org/files/flowerpotreport2.pdf; accessed January 31, 2011); and William Pittman and Robert Hunter, “A Cache of Eighteenth-Century Flowerpots in Williamsburg,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), pp. 209–13. Duguay characterizes the 548 pots and 176 saucers from five periods between 1740 and 1854 from the Château Saint-Louis in Quebec City; Goodwin and Breen cover 87 pots and 2 saucers from Mount Vernon dating to between 1775 and the modern period. Pittman and Hunter study 18 eighteenth-century pots from the John Page House in Virginia. Primarily documentary studies of flowerpots include Hazel H. Lathrop, “The Culture of Flowerpots” (master’s thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Massachusetts, Boston, 2000); and C. K. Currie, “The Archaeology of the Flowerpot in England and Wales, circa 1650–1950,” Garden History 21, no. 2 (1993): 227–46. The current article is based on analysis conducted by Rita A. DeForest, “‘A Good Sized Pot’: Early 19th-Century Planting Pots from Gore Place, Waltham, Massachusetts” (master’s thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Massachusetts, Boston, 2010).

Tamara Plakins Thornton, Cultivating Gentlemen: The Meaning of Country Life among the Boston Elite, 1785–1860 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989).

J[ohn] C[laudius] Loudon, The Green-House Companion: Comprising a General Course of Green-House and Conservatory Practice throughout the Year . . . , 2nd ed. (London: Printed by Richard Taylor, 1825), pp. 1–2.

Although there is detailed information on Gore’s field crops, we do not know what was grown in the greenhouse except for a reference at Mrs. Gore’s death in 1834 to the sale of roses and geraniums as well as orange, variegated orange, and lime trees; quoted in Lucinda A. Brockway, “Landscape History, Gore Place, Waltham, MA,” unpublished report, Past Designs for The Halvorson Group (2001), pp. 26, 28.

Goodwin and Breen, “Flowerpots of Mount Vernon’s Upper Garden,” p. 5.

Mrs. [Jane] Loudon, Gardening for Ladies; and Companion to the Flower-Garden, 2nd American ed., from the 3rd London ed. (New York: Wiley & Halsted, 1857), p. 81. Saucers, or plant trays, were numerous in the collection from the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century greenhouses around the Château Saint-Louis in Quebec City, however. See Duguay, “Utensils for the Growing of Plants,” pp. 112–15.

Currie, “Archaeology of the Flowerpot”; and Duguay, “Utensils for the Growing of Plants.”

Duguay, “Utensils for the Growing of Plants,” p. 113.

John Worrell, “Ceramic Production in the Exchange Network of an Agricultural Neighborhood,” in Domestic Pottery of the Northeastern United States, 1625–1850, Studies in Historical Archaeology, edited by Sarah Peabody Turnbaugh (Orlando, Fla.: Academic Press, 1985), pp. 153–69.

For Ingalls, see Lura Woodside Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1950), pp. 43–47. For Bradford, see ibid. For Hews, see A. H. Hews, “Pots,” in Cyclopedia of American Horticulture, edited by L[iberty] H[yde] Bailey and Wilhelm Miller, 7th ed., 4 vols. (New York: Macmillan Company, 1901), 3:1423–24; and Barbara Gorely Teller, “The Founding of a Dynastic Family Industry: The Hews, Terracotta Potters of Massachusetts,” in Turnbaugh, ed., Domestic Pottery of the Northeastern United States, pp. 249–63. For Runey, see Watkins, Early New England Potters, p. 29, and Massachusetts Society for Promoting Agriculture Records, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, box 13.

DeForest, “‘A Good Sized Pot,’” pp. 29–31.

Massachusetts Society for Promoting Agriculture Records, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston: Cambridge Botanic Garden, list of expenses, 1822, drawer C, folder xxxi, doc. 54; John Runey to Cambridge Botanic Garden, receipt, March 29, 1822, drawer C, folder xxxi, doc. 55; and John Runey to William Carter, receipt, March 16, 1830, drawer C, folder xxxii, doc. 77.

For example, C. M. Hovey, “Some Remarks on the Sizes of Flower Pots Usually Employed for Plants, with Hints upon the Importance of Having Some Standard for Classifying the Various Sizes,” in The Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs, edited by Hovey (Boston: Hovey and Co., 1837–), 5:46–50; J. C. Loudon, The Horticulturist; or, an Attempt to Teach the Science and Practice of the Culture and Management of the Kitchen, Fruit, & Forcing Garden. . . . (London: Henry G. Bohn, 1860), p. 420.

Hovey, “Some Remarks on the Sizes of Flower Pots,” 5:48–49.