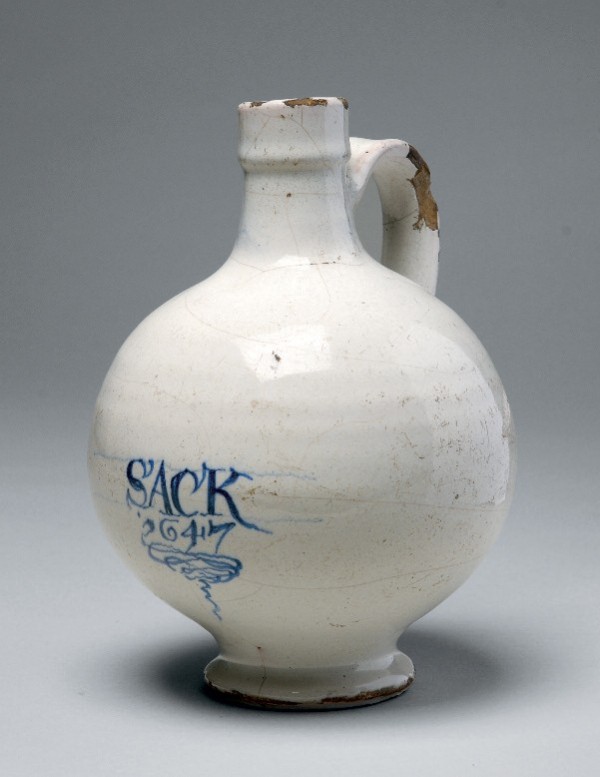

Bottle, probably Southwark, London, England, 1647. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 8". (Temple Newsam House, Holmes collection, acc. no. 2011.0329; unless otherwise noted, all objects and photography courtesy of Temple Newsam House.)

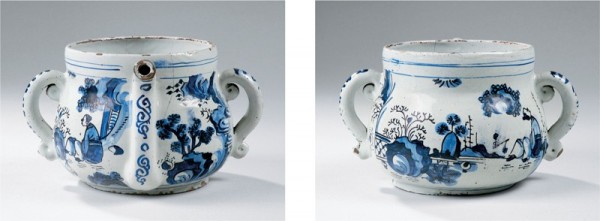

Porringer, probably Southwark, London, England, 1675–1700. Tin-glazed earthenware. L. including handle 7 3/4". (Holmes collection, 1980.0051.)

Porringer fragments, probably Southwark, London, England, 1670–1710. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Lost Towns Project, Annapolis, Maryland.) Porringers with the double-heart and round-hole handle have been uncovered at several archeological sites on the Mid-Atlantic seaboard, including Williamsburg, Virginia, and the Western Shore of Maryland. This one was excavated from Homewood’s Lot.

Mug, probably Southwark, London, England, 1650–1660. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 6 1/2". (Holmes collection, 1890.0006.)

Posset pot, London, England, ca. 1680. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 5". (Holmes collection, 1890.0004.)

Dish, possibly “WP” potter, Pickleherring or Montague Close Potteries, Southwark, London, England, 1661–1688. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 18 1/2". (Holmes collection, 1985.0035.) The dish depicts La Fécondité and includes portraits of Charles II, James II, and Oliver Cromwell. Dishes like this were modeled after ceramics made by Bernard Palissy in the sixteenth century.

Dish, tin-glazed earthenware, Bristol or Brislington, England, 1675–1725. D. 13 1/4". (Hollings bequest, 1947.0016.0486.) Painted with tulips and lesser botanicals in varying stages of bloom. The rim is decorated with blue dashes.

Dish, probably Bristol, England, 1705–1712. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 13 3/4". (Hollings bequest, 1947.0016.0485.) Decorated with a blue-dashed rim and a full-length polychrome portrait of Queen Anne.

Plate, London, England, ca. 1680. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 7 1/2". (Hollings bequest, 1947.0016.0483.4.) This plate is one of a set of six tin-glazed earthenware plates decorated with the so-called Merryman rhymes.

Plate, London, England, or the Netherlands, ca. 1680. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 7 1/2". (Hollings bequest, 1947.0016.0483.5.) The set from which this plate comes is unusually colored in ochre and manganese, possibly by Dutch artists working in London.

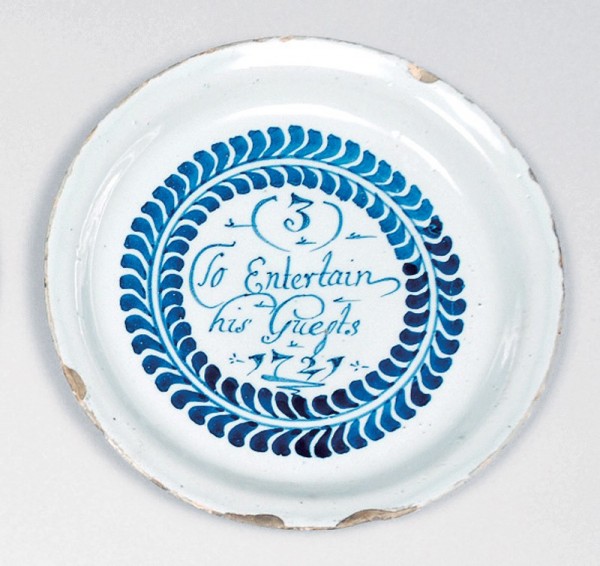

Plate, Bristol or London, England, 1721. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 1/8". (Hollings bequest, 1947.0016.0484.3.) One of six plates from another Merryman set.

Punch bowl, possibly Bristol or Brislington, England, ca. 1732. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 13 1/2". (Holmes collection, 1973.0012.) The bowl is painted with blue enamel decoration and an oval cartouche of James Edward Stuart, Prince of Wales (see fig. 13).

Oval cartouche inside the punch bowl illustrated in fig. 12. It depicts “The Old Pretender” James Edward Stuart, after a 1732 painting by T. Lilly.

Punch bowl, Liverpool, England, ca. 1760. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 12". (Holmes collection, 1979.0037.) The exterior is decorated with Fazakerley colored birds and flowers.

Interior of the punch bowl illustrated in fig. 14.

Teapot, probably London, England, 1750–1760. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 4 1/2". (Hollings bequest, 1947.0016.0478.) The teapot with molded handle and spout is painted in blue with chinoiserie scenes.

Pair of wall pockets, Liverpool, England, 1760–1770. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 7 3/4". (Hollings bequest, 1947.0016.0480.) Each wall pocket is molded and painted in enamels with birds and foliage.

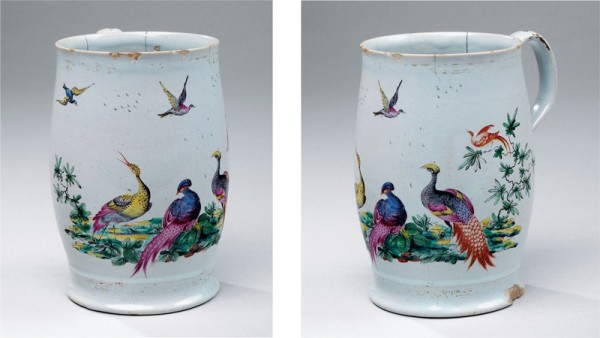

Mug, Liverpool, England, ca. 1760. Tin-glazed stoneware. H. 5 1/8". (W. Ambrose Harding collection, 1984.0040.) The painted enamels depict exotic birds and foliage.

Hand warmer, possibly Faenza, Italy, 17th century. Tin-glazed earthenware. L. 8 1/2". (Holmes collection, 2011.0327.)

Jan II van Grevenbroeck (Italian, 1731–1807), “Courtesan” from Gli Abiti De Veneziani, vol. 3, pl. 159, 1750–1807. Watercolor on laid(?) paper, 11 x 11". (Courtesy, Museo Correr, Venice.) The Italian Renaissance courtesan depicted in the painting wears a shoe similar in style and decoration to the hand warmer illustrated in fig. 19.

Wall plaque, Alcora Ceramic Factory, Alcora, Spain, ca. 1750. Tin-glazed earthenware. 21 1/2 x 34". (Frank Savery, Esq. bequest, 2011.0324.0002–003.) This plaque depicts Les amours pastorales, after a scene by French artist François Boucher (1703–1770).

Wall plaque, Alcora Ceramic Factory, Alcora, Spain, ca. 1750. Tin-glazed earthenware. 21 1/2 x 34". (Frank Savery, Esq. bequest, 2011.0324.0002–003.)

Wall plaque, Alcora Ceramic Factory, Alcora, Spain, ca. 1750. Tin-glazed earthenware. 33 x 19". (Frank Savery, Esq. bequest, 2011.0324.0001.)

Temple Newsam is a Tudor-Jacobean manor house in Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. The house was built in 1500 by Thomas, Lord Darcy. Sir Arthur Ingram added two wings in 1628 to make it a four-sided courtyard structure retaining the central block of the Tudor building.

First mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086 as “Neuhusam,” meaning New House, the property’s original structure, which once belonged to the Knights Templar, was situated approximately half a mile south of the current one. In 1909 a portion of the land was taken over by the Leeds City Council for the construction of a sewage plant. The rest of the park and Temple Newsam House itself, however, remained in private ownership until 1922, when Edward Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax, deeded it to the city, with covenants to protect it for future generations; many of the contents were dispersed at that time. Well-known to collectors of English creamware and furniture, the house is maintained and open to the public by the Leeds City Council.

The vast collections at Temple Newsam contain furniture, silver, and paintings of high quality. In addition, the collection has many fine ceramics, given in the twentieth century by collectors such as Thomas E. Hollings (d. 1947) and Mrs. Arthur Smith, who for the most part collected locally. The ceramics gifted by Hollings were particularly strong in English lead-glazed earthenware and salt-glazed stoneware.[1] Some surprising and rare English and Continental pieces were given by other Yorkshire collectors, among them John Holmes (in 1892) and Frank Savery, Esq. (1883–1965).

The collections of delft were not extensive, however. Whereas Yorkshire had its own pottery and porcelain manufacturers, including the renowned Leeds and Swinton Potteries and the lesser known Castleford and Don Potteries, none of them manufactured delftware. Temple Newsam thus began to augment its collections, through gift or purchase, to fill the gaps in early English pottery.

Delft, or tin-glazed earthenware, is a low-fired clay body with a lead glaze that includes about ten percent tin oxide, which creates an opaque surface to which enamel decoration could be added if desired. The primary delftware manufacturing centers in England were initially in London and Southwark, in Brislington from the 1640s, and, later, in Bristol and Liverpool. Delft was also manufactured in Scotland and Ireland.

The tin-glazed earthenware technology was taken from the Middle East and translated to Europe following the conquest of the Muslims in the eighth century. Wherever the wares were made, decorated examples survive in vastly greater numbers than undecorated ones, which were less expensive to produce and less valued by the consumer. In Europe the decorative apex for tin-glazed earthenware was reached in Italian maiolica in the sixteenth century, but Spain was also a serious player, albeit in a much smaller context. The Netherlands and England both played major roles in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Although it was relatively cheap, delft was friable and chipped and cracked easily. The demise of delft in England was due to the advent of the more durable and equally inexpensive salt-glazed stonewares beginning in the 1720s, although the final blows to the industry were not delivered until the later part of the century, by which time creamware had literally swept the market in the 1770s.

Most of the delft in the Temple Newsam collection is of English origin. A few pieces of European manufacture are illustrated because of their possible history of use in Yorkshire and their potential interest to readers.

From the seventeenth century is a dated 1647 bottle on which is written “SACK” (fig. 1). Sack, an inscription seen often on these bottles, was a dry white wine produced in Spain.[2]

Undecorated delftware porringers (fig. 2) were a common household item in the seventeenth century, but relatively few have survived the passage of time. Porringer fragments have been excavated from sites on Maryland’s Western Shore (fig. 3) and from unrecorded sites in Williamsburg.[3]

A few examples of “embossed” ware—delft with bobs pushed out of the clay by hand from the inside—are in the collection. They appear to have been made in Southwark and, thanks to two dated examples, can be firmly placed within 1650–1660.[4] The mug in Temple Newsam House was an early purchase from the John Holmes collection by the Municipal Art Gallery Committee in 1892 (fig. 4).

Another purchase from the Holmes collection was a posset pot (fig. 5) with Chinese-style painted figures and landscapes in blue made in London circa 1680. Posset was a concoction of hot curdled milk and wine or ale and other spices; its popularity seems to have waned after the seventeenth century with the introduction of punch. Although there are mentions of posset in the writings of Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832) and Fanny Trollope (1779–1863), the posset pot as we know it was not produced after the seventeenth century and one does not find examples of the form in porcelain or the later earthenwares.[5]

A group of important dishes after the French style of Bernard Palissy were manufactured in London in the seventeenth century, with dates occurring on examples from 1633 to 1697.[6] The so-called fecundity dish in the Temple Newsam collection (fig. 6) is a particularly important example as it portrays three prominent political figures of the time: Charles II, on the upper rim; James II, on the bottom; and Oliver Cromwell as the nemesis within the broad marley border.[7] The potter might be William Price or William Pocock, each of whom lived in the Parish of St. Saviour in Southwark and worked nearby, at either the Pickleherring or Montague Close Potteries.[8]

The tulip charger with a blue-dash border illustrated in figure 7, made in Bristol or Brislington, was one of several stylized versions of the tulip motif that was popular on English delft circa 1700. The tulip became popular in England in the late sixteenth century. The first English author to do justice to the tulip was John Parkinson (Paradisus 1629), who enumerated 140 varieties. The first known reference in Western history to the tulip was by Ogier de Busbecq, ambassador from Emperor Ferdinand I to Sulieman the Magnificent.[9] On his way from Adrianople to Constantinople in late 1554, de Busbecq observed: “We came across quantities of flowers—narcissi, hyacinths, and tulipans, as the Turks call them. . . . The tulip has little or no scent, but it is admired for its beauty and the variety of its colours.”[10] Western paintings, textiles, and pottery do not depict tulips until the end of the sixteenth century, placing de Busbecq on the cutting edge of what was to become tulip mania.

Another blue dash charger (fig. 8), also likely made in Bristol, depicts sponged trees flanking a full-length portrait of Queen Anne holding a scepter in her right hand and standing on a verdant surface of green fronds. Portraits of reigning English monarchs are iconic in English delft production. There are many large dishes depicting Queen Anne, despite her relatively brief twelve-year reign, and most of them show a standing figure. A few, for example one in the Victoria and Albert Museum and two in the Glaisher collection at the Fitzwilliam Museum, show the queen seated. A dish identical to the Temple Newsam example was formerly in the Longridge collection, and another, formerly in the Freeth collection, is currently in the Bristol Museum.[11]

The collections at Temple Newsam House have three sets of the popular delft “Merryman” plates. Two sets are from the seventeenth century, possibly of Dutch origin or made by Dutch potters in London (figs. 9, 10); a third set is dated 1727 (fig. 11). Merryman plates satirize the perennial tussle between husband and wife. They were produced in sets of six, each inscribed with its own line from the six-line rhyme:

What is a / merrey man

let him doe / what he cane

to Entertain / his Guests

with wyne / and mery jests,

but if is / wyfee dothe froune

all merriment / goes downe.

The spelling varies on different sets; on some, it is closer to Dutch than English, possibly indicating that those versions are of Dutch manufacture.

A punch bowl painted in blue bears a portrait of a man on the exterior flanked by “K” “I” and an interior oval with the same portrait labeled “KING JAMES” and, underneath the portrait, “T. LILLY 1732” (figs. 12, 13). As Louis Lipski and Michael Archer point out, it is not a portrait of James II of England, who died in 1701, but a portrait of his son, James Edward Stuart, Prince of Wales, known as “The Old Pretender.”[12] The suggestion is that the political and economic interests of the time may have favored the house of Hanoverian and Jacobite supporters, if they still existed, and that life might have been better had the crown remained on British heads.[13]

Another punch bowl (figs. 14, 15) purchased by the museum has flowers painted in the so-called Fazakerley palette of red, blue, yellow, and orange on the outside. The interior decoration, taken from an engraving, has the inscription “DUM VIVE THRIVO” in the banner linking the two lower sides of a mock coat of arms and beneath it the words “TO THE GLORIOUS INCERTAINTY OF THE LAW.” In place of the shield is a parchment with five seals hanging from it. The crest is a fox wearing legal robes and the supports are two male figures—one holds a money pouch and stands on a plough, the other stands on a harrow. In the upper part of the shield is a lawyer in his office accepting bribes, and in the lower half is a book entitled Coke upon Littleton, a reference to Sir Edward Coke’s commentary on the common law from Bracton and Littleton of 1628, which formed the basis of the British constitution.[14] A similar bowl with a variation of the print but quite different exterior decoration is in the Schreiber collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum.[15]

Teapots made in the delft body were particularly susceptible to chipping and crazing with the hot tea, and as a result were never particularly functional or popular. A blue-and-white painted example from the Hollings collection (fig. 16) has a faceted notched handle and crabstock spout and is painted with a chinoiserie landscape.

A pair of wall pockets in the form of cornucopias (fig. 17), another Hollings bequest, was molded with birds and painted in teal, greens, yellow, and blue. These are similar to a pair in the collection of Historic Deerfield in Massachusetts, both made in Liverpool 1760–1770.[16] In 1984 the museum purchased a rare enameled mug of tin-glazed stoneware (fig. 18). The mug is part of a small group of tin-glazed stonewares—fewer than two dozen—about which scholars have yet to determine how they were made or for what purpose.[17] The distinguishing feature of this mug is the polychromed enamel decoration of birds in the style of Worcester or Chelsea porcelain (most of the other identified pieces are decorated principally in blue and white). The rendering of the birds, foliage, and insects is sophisticated and could compete successfully with any porcelain example were it not for the fragility of the glaze, which plagued tin-glazed earthenwares from the onset.

A few important delft examples exist in the Temple Newsam collection that were not made in England. The hand warmer in the form of a shoe (fig. 19) is extremely rare and possibly from Faenza, Italy. Hand warmers, or scalamani, were filled with hot water and placed in a lady’s carriage under a cloak or shawl to warm hands or feet. They are found in the form of books, shoes, and boots, but this particular shape is uncommon. There is a similar shoe in the Stein collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, but the form here differs and the fabric type is more ornate. In a watercolor by Jan II van Grevenbroeck (fig. 20) a courtesan in Renaissance costume lifts her skirt and displays a similarly shaped shoe, which is open at the sides to reveal her hose.[18] Running down the front of the vamp of the shoe in Temple Newsam is a decorative band depicting a metal lace trim popular from the mid-seventeenth century into the 1680s. Shoes with square toes, latchets, and applied ribbon were fashionable in the late seventeenth century.[19] The palette suggests a northern Italy manufacture, and the Philadelphia shoe is attributed to Emilia-Romagna, probably Faenza.[20]

The last offering of tin-glazed wares in the collection is a group of three plaques made at the Alcora Ceramic Factory in Spain and given to Temple Newsam by Frank Savery in 1954. With their elaborate rococo borders and pictorial panels painted in vibrant colors, these plaques must have been produced in some numbers, as there are three in the Victoria and Albert Museum and others are known. Two of the plaques are horizontally oriented and depict European pastoral scenes.[21] One is adapted from a François Boucher (1703–1770) print, Les amours pastorales (fig. 21), the other horizontal plaque depicts the Allegory of the Earth, the reverse of a painting by Francesco Albano in the Turin Museum (fig. 22). The vertical plaque presents the biblical scene of Christ Disputing with the Doctors (fig. 23).

The collections of English and Continental tin-glazed earthenwares at Temple Newsam are explored here only in a cursory way. This brief overview publishes for the first time illustrations of many of the wonderful examples of delft housed in a collection rich in furniture, paintings, porcelains, and other earthenwares as well as textiles.

See Diana Edwards, “Salt-glazed Stoneware in Temple Newsam House, Leeds,” Antiques (July 2006): 70–77.

The term sack may have derived from the German seck but seems to have moved rapidly into general terminology for those wines produced in Jerez de la Frontera, Málaga, and the Canary Islands. In Henry IV, Shakespeare mentions sack in several passages: “If sack and sugar be a fault, God help the wicked!” (II, iv); “Unless hours were cups of sack and minutes capons and clocks the tongues of bawds and dials the signs of leaping-houses and the blessed sun himself a fair hot wench in flame-colored taffeta, I see no reason why thou shouldst be so superfluous to demand the time of the day” (I, ii); and “I’ll purge and leave sack, and live cleanly . . .” (I, v).

Al Luckenbach and Diana Edwards, “Ceramics of the Lost Towns Project: 17th- and Early 18th-Century Wares from Maryland’s Western Shore,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 18, pt. 3 (2004): 567–69; Ivor Noël Hume, Early English Delftware from London and Virginia (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1977), pp. 90–91.

In his London Delftware (London: Jonathan Horne, 1987), p. 119, Frank Britton illustrates a similar mug given to the Museum of London by J. C. Joicey, and indicates that it was made in Southwark. There is a dated example of a posset pot with embossed decoration in the Wellcome Museum of the History of Medicine at the Science Museum, London, but according to Louis L. Lipski and Michael Archer it was originally undecorated and the date was added later. Lipski and Archer, Dated English Delftware: Tin-glazed Earthenware, 1600–1800 (London: Philip Wilson; New York: Harper & Row, 1984), no. 958.

“A gold posset-dish to contain the night-draught,” in Sir Walter Scott, Kenilworth; a Romance (Edinburgh: A. Constable, 1821), chap. 6; “I do wish he would try a hot posset of a night, just before going to bed,” in Fanny Trollope, Charming Fellow II (London: Chapman & Hall, 1876), p. 205.

Graham Slater, “English Delftware ‘Palissy’ Dishes Based on ‘La Fécondité’ Design,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 17, pt. 1 (1999): 47.

This crudely painted portrait might have been taken from Sir Peter Lely’s ca. 1675 portrait of Charles II (1630–1685) in the National Portrait Gallery, London (npg 153). See Kai Kin Yung, comp., National Portrait Gallery: Complete Illustrated Catalogue, 1856–1979, edited by Mary Pettman (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1981), no. 153. Charles II became the focus for Royalist sympathizers after his father’s execution and numerous images of him were circulated. James II, brother of Charles II and his successor, immediately sought sittings for portraits directly after the Restoration. The portrait of James II (1633–1701) may have been taken from a painting by Sir Peter Lely that is in the National Portrait Gallery (NPG 5211) or possibly from a miniature in ivory after Sir Godfrey Kneller, l152(15), currently on loan to the NPG. A full-length portrait by Henri Gascus, ca. 1672–73, in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, resembles the clothing and the stance from the shoulders upward in the crudely painted miniature portrait on the dish. The portrait of Oliver Cromwell resembles a miniature portrait in the Victoria and Albert Museum painted by Andrew Benjamin Lens (b. 1708).

Slater, “English Delftware ‘Palissy’ Dishes,” pp. 58–62.

Wilfrid Blunt, Tulipomania (Harmondsworth, Eng.: Penguin Books, 1950), p. 7.

Ogier Ghislen de Busbecq, Turkish Letters (1927; repr., London: Eland, 2005), p. 16.

Frank Britton, English Delftware in the Bristol Collection (London: Sotheby Publications, 1982), p. 65, no. 3.53; Leslie B. Grigsby, The Longridge Collection of English Slipware and Delftware, 2 vols. (London: Jonathan Horne, 2000), vol. 2, Delftware, p. 66, no. D33.

Lipski and Archer, Dated English Delftware, no. 1087.

Ibid.

Peter Walton, “Acquisitions of English Pottery made for the Temple Newsam Collection since 1976,” Leeds Arts Calendar 90 (1982): 17–19.

The probable print source for the interiors of both of these bowls as published by Roger Massey is in the British Museum. English Ceramic Circle Transactions 16, pt. 2 (1997): 235–36.

Amanda E. Lange, Delftware at Historic Deerfield, 1600–1800, exh. cat. (Deerfield, Mass.: Historic Deerfield, 2001), no. 73.

Alan Smith, “An Enamelled, Tin-glazed Mug at Temple Newsam House,” Leeds Arts Calendar 82 (1978): 14–16.

Wendy M. Watson, Italian Renaissance Ceramics: The Howard I. and Janet H. Stein Collection and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, exh. cat. (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2001), pp. 141, 144.

I am grateful to Oriole Cullen and Susan North of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s textile department for advice pertaining to the dating of this shoe.

Watson, Italian Renaissance Ceramics, p. 144.

Hugh Honour, “The Ceramics of Alcora,” Leeds Arts Calendar 17, no. 24 (Winter 1954): 17.