Cabinet-on-stand, London, ca. 1700. Cabinet, oak and pine; stand, pine and basswood. H. 35 7/8", W. 38", D. 19 3/4". (Courtesy, V&A Images, Victoria & Albert Museum.)

High chest of drawers, Boston, Massachusetts, 1730–1740. Maple, white pine, and birch with white pine. H. 86 1/2", W. 38 1/4", D. 20 7/8". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1940 [40.37.1]; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Needlework picture depicting David and Bathsheba, England, late seventeenth century. 14 5/8" x 19". (Courtesy, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.)

Detail of the lower drawer of the upper case of the high chest illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

View of “ANHING” from Johan Nieuhof, Embassy from the East India Company, of the United Provinces, to the Grand Tartar Cham, Emperor of China, . . . . (London, 1673). (Courtesy, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.)

Detail of the drawer directly above the one illustrated in fig. 4. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

“CHINESE MEN” from Johan Nieuhof, Embassy from the East-India Company, of the United Provinces, to the Grand Tartar Cham, Emperor of China, . . . . (London, 1673). (Courtesy, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.)

Detail of the upper section of the high chest illustrated in fig. 2.

Detail of the decoration on the right side of the large drawer at the top of the upper section of the high chest illustrated in fig. 2. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing how the decoration continues from the right edges of the drawers on the right side of the upper section of the chest illustrated in fig. 2 to the left side of the drawers below. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) (A) On the right edge of the small drawer at the top of the upper case, a tree limb arcing up behind a small house intersects the drawer edge and disappears. But its missing portion, which matches the other half of the tree perfectly, reappears on the left-hand side of the large drawer below.

Detail showing how the decoration continues from the right edges of the drawers on the right side of the upper section of the chest illustrated in fig. 2 to the left side of the drawers below. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) (B) The bridge that appears on the right edge of the upper large drawer is repeated on the left side of the drawer below.

Detail showing how the decoration continues from the right edges of the drawers on the right side of the upper section of the chest illustrated in fig. 2 to the left side of the drawers below. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) (C) The flowers on the right side of the second large drawer from the top continue as foliage behind the house on the left-hand side of the drawer below.

Detail showing how the decoration continues from the right edges of the drawers on the right side of the upper section of the chest illustrated in fig. 2 to the left side of the drawers below. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) (D) The fences and trees on the right side of the third drawer down reappear behind the houses on the left side of the bottom drawer.

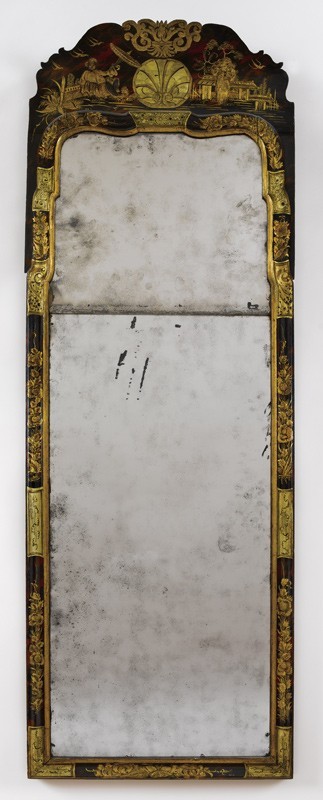

Looking glass, Boston, Massachusetts, 1730–1740. White pine. H. 57 1/2", W. 19 1/8", D. 1 1/4". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1940 [40.37.4]; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the crest of the looking glass illustrated in fig. 11. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

William Burgis, South East View of the Great Town of Boston, Boston, Massachusetts, 1743. 9 7/8"x 20 7/8". (Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.)

High chest of drawers, Boston, Massachusetts, 1730–1740. White pine and maple with white pine. H. 95 3/4", W. 42", D. 24 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

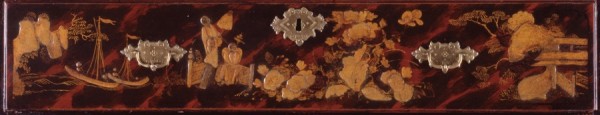

Detail of the decoration on a drawer from the upper case of the high chest illustrated in fig. 14.

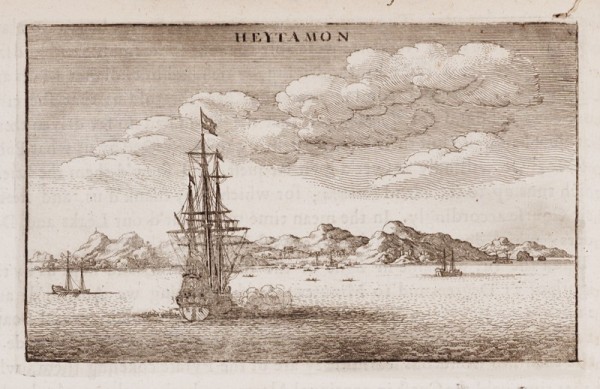

View of “HEYTAMON” from Johan Nieuhof, Embassy from the East-India Company, of the United Provinces, to the Grand Tartar Cham, Emperor of China, . . . . (London, 1673). (Courtesy, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.)

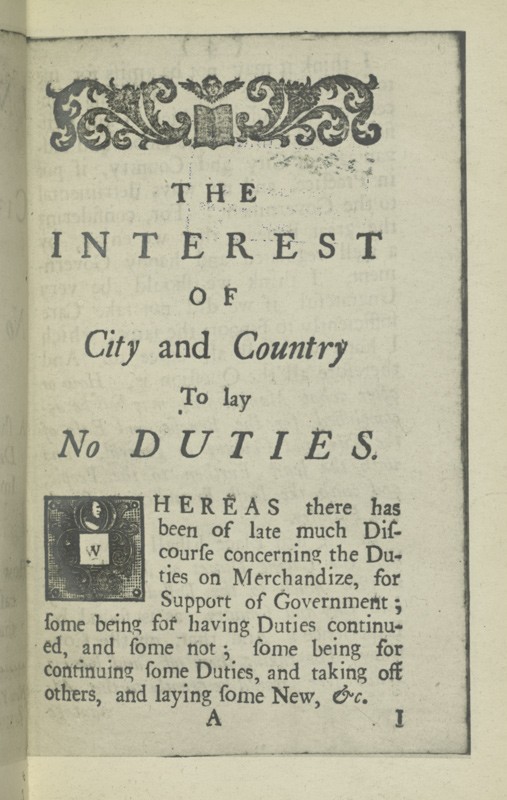

Detail of the opening page of chapter one of The Interest of City and Country to Lay No Duties (New York, 1726). (Courtesy, New York Public Library.)

High chest of drawers, Boston, Massachusetts, 1710–1720. White pine and maple with white pine. H. 61", W. 40 1/4", D. 22". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the decoration on the upper case of the high chest illustrated in fig. 18. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Recently scholars have interpreted works of literature by focusing on the way in which authors describe and characterize material objects, including pieces of furniture. This essay attempts a similar, but slightly reformulated, version of that project: it endeavors to reveal period-specific meanings of furniture by considering several different genres of literature. Its focus is a group of japanned cabinets-on-stands and high chests of drawers made in late-seventeenth- and early-eighteenth-century London and Boston (figs. 1, 2, 14, 18). The adjective “japanned” refers to the exotic surface ornament of the objects. This ornament, which includes gold-colored human figures, bouquets of flowers, flocks of birds, and rows of pagoda-roofed houses, resembles the imagery on the Asian lacquerware screens and boxes that were imported into Boston and London from China and Japan in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Despite the furniture’s Asian connotations, Western craftsmen, known as japanners, decorated surfaces of the japanned cabinets and high chests. These craftsmen, whose names are largely unknown today, practiced a labor-intensive and expensive craft. Wealthy merchant families purchased many of the japanned objects that were produced during the style’s height of fashion, from roughly 1680 to 1740. Wills and inventories suggest that these families often owned a range of japanned objects, from high chests and cabinets to dressing tables, chairs, and mirrors.[1]

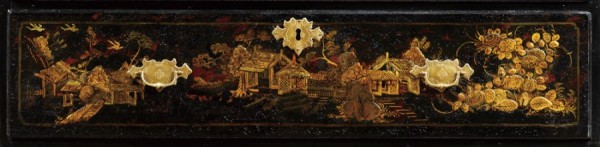

Dozens of japanned high chests and cabinets survive from late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century London and Boston. Although concerned with this entire class of objects, this essay concentrates on a single exemplary piece: a high chest made in Boston between 1730 and 1740 (fig. 2). This object is one of the best-preserved examples of japanned furniture, in that the decoration that covers most of its surface is original. There are identical images of buildings and trees on its sides; abstract, curvilinear patterns on its legs and moldings; cherub heads on its pediment; and, most spectacularly of all, clusters of images on each of its ten drawer fronts.[2]

The first owner of the chest was probably Benjamin Pickman, a wealthy merchant from Salem, Massachusetts. Like many of the owners of japanned furniture, Pickman made a fortune shipping and exchanging various types of commodities between Boston, London, Portugal, and ports to the south, including the West Indies. The high chest is thought to have stood in Pickman’s home on Union Street in Salem. There it would have served as both a showpiece and a container for household goods such as bed linens and clothing.[3]

Generations of English and American furniture historians have studied Pickman’s high chest and other surviving japanned furniture from the period. Their analyses primarily address connoisseurial questions. Focusing closely on artifactual evidence and consulting primary sources such as wills, inventories, and treatises, scholars have studied the process of japanning, have carefully authenticated the japanned objects in museums and private collections, and have attributed a small percentage of these objects to the hands of individual period craftsmen. (Pickman’s high chest has been loosely attributed to Thomas Johnston, a Boston craftsman. Johnston worked primarily as an engraver, but he also advertised his services as a japanner in the 1730s.) Beyond these connoisseurial studies, scholars have drawn two general conclusions about japanned furniture. First, they argue that it, like many household goods from the early eighteenth century, was used to broadcast its owners’ wealth and status. Second, they tie japanned furniture to the eighteenth-century taste for chinoiserie, or Asian-style, domestic objects.[4]

This essay does not dispute these conclusions, nor does it question the connoisseurial studies—indeed, it relies on their findings and employs their method of close analysis. However, in addition to the standard sources of the furniture historian—wills, inventories, and treatises—I also turn to other forms of literature, including professional manuals, novels, and poems. These works help reveal a long-overlooked aspect of objects like Pickman’s high chest: their literary function. I first argue that japanned high chests and cabinets are narrative objects whose ornament tells a story. I then address questions of audience and reception. Although scholars have long associated the chinoiserie style with women, I argue that these narrative objects cater equally to a masculine, and specifically mercantile, sensibility.

Furniture as Literature

The best point of entry into the narrative character of the high chests and cabinets is John Stalker and George Parker’s Treatise of Japanning and Varnishing (1688), which outlines the process of japanning. Intended, in its authors’ words, for both “practitioners” and the “ingenious gentry” who owned japanned furniture, the treatise carefully describes the steps necessary to transform a piece of pine into a spectacular surface of gesso and gilt. In certain passages, however, Stalker and Parker digress from their discussions of method to describe the appearance and character of japanned furniture. These descriptions are important because they provide insight into the ways in which period viewers thought about objects such as Pickman’s chest. The descriptions focus principally on japanning’s visual splendor. Stalker and Parker use phrases such as “delightful and ornamental beyond expression” and words such as “beautiful,” “rich,” and “Majestick” to characterize the style. Yet in other passages, the authors describe japanned furniture in very different terms. At the conclusion of the preface, for example, they write that japanned furniture “calls to mind the fictions of the poets.” Pages later, they note that some of this furniture risks being “registered in doggrel ballad.” At other points, they refer to japanning’s “errata,” “passages,” and “conclusions,” and they speak of the object’s “author” and his “pen.” By aligning japanned objects with narrative forms and narrative structures, these characterizations indicate that Stalker and Parker and, by extension, their readers thought that there was something storylike about japanned furniture.[5]

Today, one is tempted to dismiss Stalker and Parker’s descriptions as poetic license. Japanned furniture, after all, presents pictures, not words, which are generally considered the primary ingredient of “fictions,” “poems,” and “ballads.” Narratives, though, as scholar Mieke Bal has explained in her extensive writings on the subject, can be presented in a variety of media, including images. In eighteenth-century London and Boston, where literacy rates were low, stories told through images were common. In Boston, they surfaced in children’s books such as the New England Primer, whose pictures told stories to help children learn to read. In London, they appeared in public spaces such as churches, where stained-glass windows presented stories from the Bible. In both cities, significantly, they could be seen on a variety of domestic objects. The homes of early-eighteenth-century Boston and London elites contained many narrative objects. These included imported porcelain vases decorated with images that told the story of the hunt by showing its different stages (the successive spotting, tracking, and killing of the deer), porcelain plates that told the story of a voyage from Canton to London by showing the same ship at various points between the two coasts, and panels embroidered with colorful images that presented familiar stories from the Bible. One such panel from 1680s London tells the story of King David’s seduction of the beautiful Bathsheba (fig. 3). At the upper left corner of this object is an image of Bathsheba’s initial seduction; below that, an image of David deliberating with her husband; at the upper right corner, an image of Bathsheba’s husband being murdered; and, finally, in the lower right corner, an image of the concluding moment in the story, when the prophet Nathan admonishes David for his behavior. It is crucial to understand that the images in all of these examples are not just illustrations. By presenting the same characters (the deer, the hunters, the ship, David) at different times in different places, they tell stories—and constitute narratives—themselves.[6]

Japanned furniture can be counted among these narrative objects. The exotic images on Pickman’s chest do not, of course, tell a story from the Bible. Rather, they tell a version of the stories of exotic cultures that were presented in one of the most popular literary genres of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, sea narratives. This genre consisted of works such as William Symson’s New Voyage to the East Indies (1715) and William Betagh’s Voyage Round the World (1728). As these titles suggest, English explorers who had circumnavigated the globe or sailed to its “unknown” coasts, places such as Asia and the Indies, were the authors of the sea narratives. These explorers were famous for the painstaking observations they made in their attempts to record every aspect of the coastlines they encountered, from their geography to their human inhabitants to their commercial opportunities. The result was a series of best sellers: the sea narratives were read by a wide variety of social groups in Boston and London, including the cities’ craftsmen. Art historians Carl Dauterman and Leslie Grigsby have shown that both English silver chasers and ceramists decorated their vessels with images based on illustrations from this kind of travel book.[7]

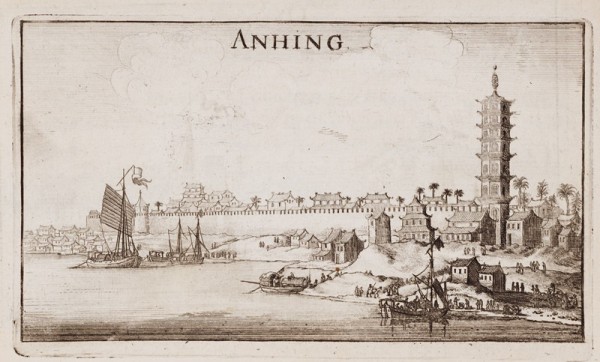

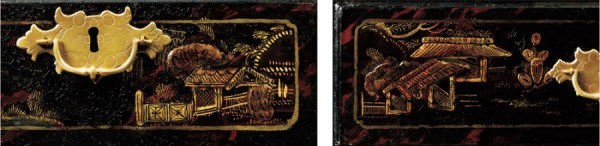

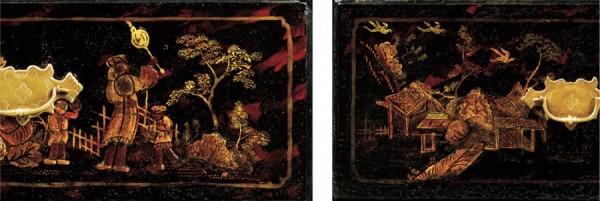

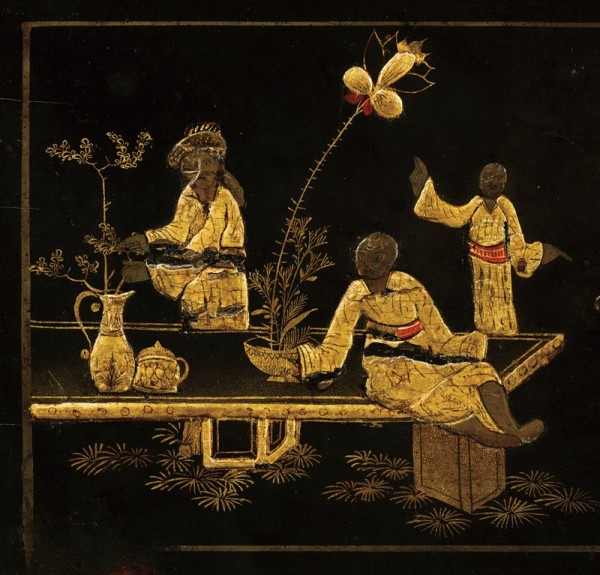

The japanners of London and Boston went a step further. They created objects that actually told sea narratives rather than objects that simply resembled the narratives’ illustrations. We can begin to understand how japanned furniture tells a story by considering the way the images on the Pickman high chest echo two of the sea narrative’s essential characteristics. First, they evoke a location that almost all of the sea narratives illustrate and describe, the Asian coast. Comparing the japanned surface to the images of the coastline that appear in one of the most lavishly illustrated sea narratives, Johan Nieuhof’s Embassy from the East-India Company . . . (1673), makes this connection clear. The houses on the lower drawer of the upper case of the Pickman chest (fig. 4) bear a strong resemblance to the small town pictured in Nieuhof’s engraving of the Anhing section of the Chinese coast (fig. 5). Like the houses in this image, the buildings on the high chest are horizontally proportioned and positioned low to the ground and close to one another in a single line. Similarly, the figures on the drawer above (fig. 6) are depicted in the manner of the coastal inhabitants illustrated in Nieuhof’s book (fig. 7). Like Nieuhof’s engraving of “Chinese Men,” the high chest presents small groups of men and children walking across the landscape wearing loose, flowing clothing.[8]

In addition to these details, other images on the japanned surfaces correspond to aspects of the Asian coastline that the authors of the sea narratives discuss in their texts (fig. 8). Many of the images, for example, relate to the descriptions of the coast of St. John’s, an island off China, in William Dampier’s A New Voyage Round the World, a best-selling sea narrative published in its fifth edition in 1729. The two long-necked birds stationed behind the keyhole on the uppermost large drawer and the small birds hovering on the bottom drawer resemble the “tame fowls . . . ducks and cocks and hens and small birds” that Dampier described flying around the coast, the triangular bridges on the upper large drawer call to mind the bridges he encountered, and the figures spread across each drawer of the high chest resemble the inhabitants the captain observed as he sailed toward the island. As he notes,

The natives of this island are Chinese . . . the Chinese in general are tall, straight-bodied, raw-boned men. . . . The Chinese have no turbans, but when they walk abroad, they carry a small umbrello in their hands, wherewith they fence their heads from the sun or the rain, by holding it over their heads. . . . The common apparel of the men is a loose frock and breeches.[9]

The figures on the high chest match Dampier’s description: they wear loose frocks and breeches, lack turbans, and—in the case of the figure on the far right side of the detail shown in figure 9—hold umbrellas. Dampier later describes the way that the inhabitants of the coast “gazed on us as we past by.” The figures on the high chest also match this aspect of the coastal inhabitants. All of them appear to look out at some presence beyond their immediate landscape.[10]

The connections between the japanned surface and the coastlines discussed in the sea narratives, however, are more than a matter of these details. Looking closely reveals that the entire japanned surface represents the kind of place that the sea narratives describe. That is to say, the japanner organized the images into a coherent whole. Although the images on each drawer of the high chest appear to be separated into discrete, horizontal units, they are, in fact, closely linked. The image on the far right side of each drawer corresponds directly to the image on the far left side of the drawer below (fig. 10). This pattern, which extends to the drawers below the waist molding, presents the images on the high chest’s drawers as one continuous, linear image that is similar to those featured on the Asian screens and scrolls that inspired many of the motifs used in japanning. Indeed, if one were to line up the drawers side by side, one could view a panorama of the kind of coastline that the authors of sea narratives such as Embassy from the East-India Company and A New Voyage Round the World explored.[11]

The similarities between the high chest and the sea narratives run even deeper. In addition to their setting, they share the same point of view. Captains such as Dampier and Nieuhof typically viewed and described the coast from the perspective of their ships. For example, Dampier views the shore from his “canoa” and takes note of the gaze of the coasts’ inhabitants as he “pas[ses] by.” Similarly, the large body of water in the foreground of Nieuhof’s image of Anhing (fig. 5) indicates that he portrayed this coast as he viewed it from the deck of a ship still at sea. The japanner of the Pickman chest rendered the coastline on the high chest from this same “ship’s-eye” perspective. The horizontal lines that appear in front of the houses on the pediment drawers, in front of the fences below the waist molding, and in front of the figure on a japanned mirror that scholars believe Pickman bought at the same time as the high chest all make this clear (figs. 11, 12). These lines match those that engravers used to depict waves in period views of Boston, such as William Burgis’s 1743 view of the city from the southeast (fig. 13). The position of these lines in the foreground of the high chest’s landscapes indicates that there is water in front of the coast, and thus that it is viewed from the sea. The images on other pieces of japanned furniture sometimes signal this perspective more explicitly. One high chest from the 1730s, for example, shows a boat sailing in front of a rocky coastline, indicating unambiguously that the view is from the water (figs. 14, 15). Similar boats cruise past the landscapes depicted on several other contemporaneous English chests.[12]

Pickman’s high chest thus represents the same region of the world that the sea narratives describe, and it does so from a similar ship’s-eye point of view. Despite these similarities, the Pickman chest and the sea narratives differ in one important way. Because the sea narratives are characterized by a strong authorial presence in their prose and illustrations, the reader of works such as A New Voyage Round the World is always at a remove from the discovered coast. Dampier consistently writes in the first person: “I shall now add this account,” “I will share my observations,” and the illustrations often show the author in the act of encountering the things he writes about, as opposed to just showing what he encountered. In many of the images of the Asian coast in Nieuhof’s Embassy from the East-India Company, for example, the author’s ship, shown as such by its Western design and Dutch flag, presides in the foreground (fig. 16). These marks of the author make the reader very aware that he is reading about the explorer’s adventures and learning about the exotic coast through the explorer’s mediating eyes. Daniel Defoe makes this clear in his unfinished 1731 work The Compleat English Gentleman, in which he writes that A New Voyage Round the World invites the reader “to go round the globe with Dampier” (my emphasis). To read a sea narrative, then, is to experience exotic places but to do so only secondhand, with the author as a filter and a guide.[13]

On the japanned surface, in contrast, there are no obvious signs of authorial presence. The images on the high chest match the coasts that the sea narratives describe and they match the point of view that the authors had of those coasts, but they do so without depicting the Western ship that marks the presence of the author-explorer. As a result, the viewer has the illusion of an unmediated, “first-person” experience of exploration and discovery. With the right amount of imaginative engagement, a viewer can assume the captain’s place in the “canoa” and experience the coast firsthand. Ultimately, she or he can observe and come to know the coastline on the chest’s surface just as Dampier came to know the coast of China.

This is the sense in which the images on the surface of the high chest tell a story. This story chronicles the reader’s own exploration and discovery of the exotic coastline. The japanner actually arranged the images to imply the progress of an explorer: the ship’s-eye view is that of a gradually approaching vessel. At the top of the high chest, the “ship” is only close enough to allow the viewer to see buildings; as it “sails in closer” in the middle drawers, figures become visible; and, finally, on the drawer above the molding, it retreats to a point from which once again only buildings are visible. To paraphrase Defoe, then, the viewer of the high chest does not go round the world with Dampier, he goes as Dampier himself.

Two pieces of evidence solidify this interpretation. The first is the Treatise on Japanning and Varnishing. Authors Parker and Stalker conclude their discussion of japanning by describing the opportunity for a firsthand experience of exploration as one of the primary attractions of their style: “I had rather see an embassy thus in miniature than go to China that I might really behold one.” The authors refer to the experience of exploration in other passages as well. They advise the viewer of the japanned surface to expect a “Terra incognita and undiscovered provinces,” and they salt their volume with nautical metaphors. The process of placing ornament on the surface is like that of “a ship that ploughs and divides the sea, makes a channel in an instant, but as it sails off, the waters return”; the process of following the plates they lay out for japanners to copy is like “sailing between this scylla and charybdis, passing the rock on one hand, the gulph on the other.” These references are important both because they shed light on the meaning of the Pickman chest and because they suggest that other pieces of japanned furniture likewise present sea narratives.[14]

The second piece of evidence that buttresses this interpretation specifically concerns Pickman’s high chest. The japanner arranged its images in a manner that calls to mind the site in which the sea narratives were originally presented, the printed page. The left-to-right and top-to-bottom linear sequence (created by the repetition of the form at each drawer’s right edge on the left edge of the drawer below, as described above) makes each drawer function like a line of text that is interrupted at the right margin but that resumes on the left-hand side of the line below. The cherub heads placed around the pediment also resemble a type of decoration common in early-eighteenth-century books. Engravers, including Thomas Johnston, the Boston craftsman thought to have japanned the Pickman chest, placed similar heads at the tops of title pages and at the beginnings of chapters (fig. 17). The heads on the high chest occupy a similar position: stationed at the top of the high chest, they call attention to the beginning of a “text” composed of pictures and thus emphasize the way that the surface tells a story.[15]

It is no wonder, then, that Stalker and Parker used words such as “ballad” and “fiction” to describe japanned furniture. For what the viewer, or “reader,” of a japanned high chest encountered was not just a visually striking, exotic object but a piece of furniture that told a captivating tale of discovery, one in which the viewer-reader played a starring role.

Audience

Scholars have long associated chinoiserie goods, including japanned furniture, with women. The arguments in one recent book are typical: “In Restoration London,” writes historian David Mitchell, “it was in the chambers, dressing rooms and closets of the wives of City merchants . . . that porcelain, japanned furniture and Oriental textiles were most commonly found.” Significant historical evidence supports this assertion. Inventories suggest that japanned furniture stood in the women’s spaces of the home; treatises directed at amateur japanners have titles—The Art of Japanning Published at the Request of Several Ladies and Ladies Amusement, the Whole Art of Japanning Made Easy—that propose these practitioners were often female; and, most significantly, period literature connects japanned furniture with women. Alexander Pope, for example, associated japanned decoration with the subject of his 1710 poem “Chloe”: “She while her lover pants upon her breast / Can mark the figures on an Indian chest.” (Britons and Anglo-Americans used the word “Indian” to refer to all Asian peoples.) Also in 1710, in his “Advice to an Author,” the Earl of Shaftesbury sarcastically commented, “Effeminacy pleases me. The Indian figures, the Japan work, the enamel strikes my eye.” The feminine connotations of japanned furniture were operative well into the mid-eighteenth century; in 1762 Swedish painter Olof Fridsberg pictured a woman in an interior that featured a japanned chest.[16]

This evidence would seem to suggest that the Pickman chest and others like it were intended for a female audience, and indeed, the literary character of japanned furniture probably added to its appeal for women. Women of the classes that could afford japanned furniture spent significant time reading in the early eighteenth century, and they often acquired and produced domestic goods, such as ceramics and needlepoint, that told stories with pictures. Yet other evidence points to an audience broader than that of the typical chinoiserie object. Close examination of the japanned cabinets and chests indicates that this furniture caters to a decidedly masculine and particularly mercantile sensibility.[17]

The first indicator that the story on the Pickman chest caters specifically to men is the fact that it positions the viewer in a role with which (male) merchants were especially familiar. Though any member of an English or American household could probably imagine him- or herself as an explorer viewing a coast from the deck of a ship, the merchant could assume this position quite literally, for many such men had firsthand familiarity with the explorer’s perspective. Early in their careers, they had often sailed on ships as captains or as travelers and had seen the coast from a similar point of view. Merchants who did not have this experience also were adept at assuming the deck-of-the-ship perspective. As owners of and investors in trading ships, they spent time planning the courses of sea voyages. Many of the maps they were likely to have consulted in this process portrayed coastlines from the sea and thus habituated the merchant to the captain’s position.[18]

The deck-of-the-ship perspective that the japanners adopted also asks the viewer to assume a role that male merchants particularly, even feverishly, desired: that of explorer. Many of the merchants portrayed in the era’s new realistic novels and plays fantasize about exploring distant shores. Robinson Crusoe, son of a merchant in Defoe’s 1719 story, is distracted by his wish “to see the world”; Lemuel Gulliver from Jonathan Swift’s story of 1726 has an “insatiable desire to see foreign lands”; and George Barnwell, the aspiring merchant in George Lillo’s 1731 play The London Merchant, speaks of “quit[ting] his ease and trust[ing] to rocks and sands and stormy seas; in hopes [of] some unknown golden coast to find.” Exploration appealed to these merchants not only because of the prospect of encountering exotic places but also for the opportunity to discover new markets in which to buy and sell goods, and, ultimately, from which to grow rich. Thus, the merchants in Lillo’s play describe “the populous east, luxuriant” that “abounds with glittering gems, bright pearls,” while Gulliver, who eventually submits to his desires and sails to a coastline populated by miniature figures like those on the japanned surface, likewise emphasizes the “commerce” and the “marketplace” in the places he discovers.[19]

The japanned story invites its reader to fulfill these fantasies of what one might call commercial discovery. For it not only offers the reader an experience of exotic peoples and animals, but it also gives him the chance to encounter a range of commercial opportunities. Though Pickman’s chest makes no direct allusions to commerce, other japanned high chests show figures selling goods, signaling that the coast is ready to trade. On one high chest built in Boston in the 1720s, for example, japanned figures stand around a table that displays the kind of porcelain wares—teapots, bowls, and pitchers—that the English actually brought back from China (figs. 18, 19). On a more basic level, the gold colors of the japanned surface emphasize that the coastline is a place so wealthy, as the nameless author of The Pleasant and Profitable Companion wrote of China in 1733, that “all the bridges, doors, Gates, tops of the windows . . . and all the roofs of the houses were cover’d with Plates of gold.”[20]

The implied masculine audience for the high chests is not only a matter of the way these objects appealed to merchants’ daydreams of exploration and wealth. These objects also affirmed and effectively taught their viewers what merchants, in their professional role as traders, viewed as the proper way to approach material objects. The many treatises written while japanning was at the height of fashion to educate aspiring and practicing merchants counseled their readers to observe and build a comprehensive knowledge of the objects they exchanged. In 1734 English author Edward Hatton opened his treatise The Merchant’s Magazine by noting that the merchant had to have “clear notions” of “the quality of the most material and best commodities.” Lewes Roberts treated this subject more extensively in his book The Merchant’s Map of Commerce, published in its fourth edition in 1700. This work, intended for the edification of “all merchants . . . in any part of the habitable world,” devotes an entire chapter to the importance of the merchant’s knowledge of “commodities in general.” Roberts writes, “a principal part of [being a merchant] is to know and learn” commodities. He must have “unlimited knowledge” of them and “have a generall inspection in every part and member of them,” from their “colours” to their “goodnesses, substance, vertue, taste, seeing, or feeling.” This knowledge, Roberts notes, “is best gotten by often viewing the same, and heedfully marking the qualitie and properties thereof.”[21]

The story on the japanned surface invites its reader to approach a material object in precisely this manner. For insofar as it asks a viewer to consider a piece of furniture from the point of view of an explorer, it puts him in a position from which he is expected to closely observe and “heedfully mark” all of the properties of the object. Certain period writings actually allude to the benefits of viewing commodities with a captain’s careful eye. For example, Swift’s 1730 poem “The Lady’s Dressing Room” details Strephon’s exploration of his lover’s dressing room and his “strict survey” of the objects in this space, which included a chest. This “survey,” a kind of looking characteristic of sea narrative explorers, reveals that the chest is not quite what it seems. As Strephon “ventur’d” to consider the chest, he realized that though it looked like an expensive cabinet with drawers that opened from the front, it was in fact a less expensive chest whose top opened up: “In vain, the Workman shew’d his wit / With Rings and Hinges counterfeit / To make it seem in this Disguise, / A Cabinet to vulgar Eyes.” By inviting the viewer to “survey” and “venture” through a real object, the japanned story thematizes the close looking that Swift describes.[22]

The japanned narrative instructs its reader in the proper way to look at an object in another respect, too. Roberts writes that the close observation and knowledge of the commodity had a single objective:

Neither yet must his knowledge rest it selfe here upon the consideration of the meere goodnesse of commodities, but must also extend it selfe to the consideration of the true worth and value thereof . . . their maine scope and aime should be to make this knowledge and skill profitable and beneficiall unto them.

To move from “knowledge” to “value” and thus to profit, a merchant needed to make a deduction: he had to translate the “goodness” of the commodity into a monetary price. The japanned story calls for its reader to execute just this kind of conversion. Insofar as it caters to the merchant’s fantasies of commercial discovery, it invites him to extrapolate his observations about the coast into an assessment of its value.[23]

Despite the imaginative engagement it invites, the japanned story ultimately imparts a very practical lesson. With every “sail” past the japanned coast, the viewer is subtly reminded of the proper way to engage with a commodity. An object such as a high chest or cabinet was a particularly appropriate means by which to convey such a reminder. As a permanent fixture in the home, it constantly broadcast its lessons. Moreover, furniture was itself a traded commodity in the early eighteenth century. Chairs and sometimes chests were actively exchanged between Boston and London and other colonial ports. The kind of looking that japanning encouraged was thus especially relevant to the type of object it ornamented.[24]

One is thus led to question or at least to qualify the nature of the audience typically associated with japanned furniture. Though women no doubt “read” these literary objects, most japanned high chests and cabinets catered to a masculine, mercantile sensibility. These objects brought the imaginative life and perceptive modes of the countinghouses into the home.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For their valuable insights and assistance, the author thanks Dennis Carr, Edward S. Cooke Jr., Karina Corrigan, Carma Gorman, Jennifer Raab, Jessica Roth, and the American Art Reading Group at Yale University. Particular thanks are also owed to David Raizman for his enthusiasm and encouragement. A version of this essay was first published in David Raizman and Carma Gorman, eds., Objects, Audiences and Literatures: Alternative Narratives in the History of Design (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Press, 2007). The author thanks Cambridge Scholars Press for granting permission to reprint the article.

For interpretations of literature, see Bill Brown, A Sense of Things: The Object Matter of American Literature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003) and Things, edited by Bill Brown (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004). The high chest of drawers was principally a Boston form. The cabinet-on-stand was principally a London form. However, examples of each object existed in both Boston and London. See Benno Forman, “The Chest of Drawers in America, 1635–1730: The Origins of the Joined Chest of Drawers,” Winterthur Portfolio 20 (spring 1985): 1–30. For images of the two types of objects, see John Kirk, American Furniture and the British Tradition to 1830 (New York: Knopf, 1982). Often the cabinets-on-stands had doors. My arguments, however, concern the decorated surfaces behind these doors. For lacquerware examples, see Hans Huth, Lacquer of the West: The History of a Craft and an Industry, 1550–1950 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971); and Adam Bowett, English Furniture, 1660–1714: From Charles II to Queen Anne (London: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2002). Most japanned objects with known provenances are associated with wealthy merchant families in Boston and London. For London, see David Mitchell, “A Passion for the Exotic,” in City Merchants and the Arts, 1670–1720, edited by Mirelle Galinou (London: Oblong, 2004), pp. 72–82. For Boston, see Phyllis Hunter, Purchasing Identity in the Atlantic World: Massachusetts Merchants, 1670–1780 (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2001), pp. 117–18; and Dean Fales, “Boston Japanned Furniture,” in Boston Furniture of the Eighteenth Century, edited by Walter Whitehill (Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1972), pp. 49–71. Fales lists many of the merchant families that owned japanned objects in Boston, including the Governor James Bowdoin family, the Captain Joshua Loring family, and the Benjamin Pickman family. On the period of japanning’s fashion, see Huth, Lacquer of the West, pp. 36–51.

Many of these objects are discussed in Fales, “Boston Japanned Furniture,” pp. 49–71; Huth, Lacquer of the West, pp. 36–41; and Bowett, English Furniture, pp. 144–69. The Boston high chest is discussed in Morrison Heckscher, American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Late Colonial Period: The Queen Anne and Chippendale Styles (New York: Random House, 1985), pp. 241–43; the condition of the object is discussed in Morrison H. Heckscher and Frances G. Safford, “Boston Japanned Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” Antiques 129, no. 5 (May 1986): 1049. Heckscher dates the high chest to 1730–1750. I have narrowed his date to a shorter, decadelong period for three reasons. First, several similar high chests from Boston have been dated to this decade; second, the likely japanner of the high chest, Thomas Johnston, was particularly active in this decade (for more on Johnston, see Heckscher, American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, p. 240; and Elizabeth Rhoades and Brock Jobe, “Recent Discoveries in Boston Japanned Furniture,” Antiques 105, no. 5 [May 1974]: 1082–91); and third, Benjamin Pickman, the original owner, was married in 1731, and high chests were often presented as wedding gifts. The case for this object as exemplary is made throughout this essay; I consistently show how my arguments about Pickman’s high chest apply to japanned furniture more broadly. Japanned furniture is well suited to this kind of case-study approach because its ornament is so consistent. Though individual objects were made by different hands, the surfaces of the objects, as Bowett writes, “varied little over the period” when they were in fashion (Bowett, English Furniture, p. 162).

This provenance follows from a family history. See Heckscher, American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, p. 240. Pickman traded in barrels, wood, codfish, vinegar, and rum. See James Phillips, Salem in the Eighteenth Century (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1937), pp. 244–56; and The Diary and Letters of Benjamin Pickman (1740–1819) of Salem, Massachusetts with a Biographical and Genealogical Sketch of the Pickman Family, edited by George Francis Dow (Newport, R.I., 1928).

For process, see John Hill, “The History and Technique of Japanning and the Restoration of the Pimm Highboy,” American Art Journal 8 (November 1976): 59–84; R. W. Symonds, “The Craft of Japanning,” Antique Collector, September–October 1947, 149–54; R. W. Symonds, “The Craft of Japanning, Part II,” Antique Collector, November–December 1947, 183–89. For museums and private collections, see Bowett, English Furniture; Fales, “Boston Japanned Furniture”; J. Michael Flanigan, American Furniture from the Kaufman Collection (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1986), pp. 50–53; Heckscher and Safford, “Boston Japanned Furniture”; Huth, Lacquer of the West; Danielle Kisluk-Grosheide, “A Japanned Cabinet in the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 19–20 (1984–1985): 85–95; Rhoades and Jobe, “Recent Discoveries”; Nancy Richards and Nancy Goyne Evans, New England Furniture at Winterthur: Queen Anne and Chippendale Periods (Winterthur, Del.: Winterthur Museum, 1997), 304–9; and David Warren, American Decorative Arts and Paintings in the Bayou Bend Collection (Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1998), pp. 44–46. For attributions, see Rhoades and Jobe, “Recent Discoveries”; Richard Randall, “William Randall, Boston Japanner,” Antiques 105, no. 5 (May 1974): 1127–31; and Skinner, American Furniture and Decorative Arts, Boston, Massachusetts, November 7, 2004, lot 230. A design book created by Boston japanner Jean Berger is reproduced in Robert Leath, “Jean Berger’s Design Book: Huguenot Tradesmen and the Dissemination of the French Baroque Style,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1994), pp. 137–62. For Johnston, see Heckscher, American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, p. 240. For a discussion of Johnston and other Boston japanners, see Rhoades and Jobe, “Recent Discoveries.” For japanning and social status, see Hunter, Purchasing Identity, pp. 117–18. For japanning and the taste for chinoiserie, see Hugh Honour, Chinoiserie: The Vision of Cathay (New York: Harper & Row, 1961), pp. 64–67; and Oliver Impey, Chinoiserie: The Impact of Oriental Styles on Western Art and Decoration (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1977), pp. 111–29.

John Stalker and George Parker, A Treatise of Japanning and Varnishing (Oxford: printed for the authors, 1688), Epistle 25. For a discussion of the continued use of this publication in the eighteenth century, see Hill, “The History and Technique of Japanning and Restoration of the Pimm Highboy,” p. 61. Stalker and Parker, Treatise, preface, pp. 9, 29.

Mieke Bal, Narratology (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002). For vases, see Ronald Fuchs, Made in China: Export Porcelain from the Leo and Doris Hodroff Collection at Winterthur (Hanover, N.H.: University of New England Press, 2005), p. 169. For plates, see Kee Il Choi, “Hong Bowls and the Landscape of the China Trade,” Antiques 156, no. 4 (October 1999): 500–509. For panels, see Mary Brooks, English Embroideries of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries in the Collection of the Ashmolean Museum (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2004), p. 12.

Philip Edwards, The Story of the Voyage: Sea Narratives in Eighteenth-Century England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), pp. 2–3. English writer the Earl of Shaftesbury identified these “wonders of the terra incognita” as the “chief material to furnish out a library.” See his Soliloquy or Advice to an Author (London, 1710), p. 178. William Dampier, author of A New Voyage Round the World, one of the most widely read sea narratives, even conceded that he chose “to be more particular than may have been needful.” William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World (1697; reprint, London: Argonaut Press, 1927), p. 3. Leslie Grigsby, “Johan Nieuhof’s Embassy: Inspiration for Relief Decoration on English Stoneware and Earthenware,” Antiques 143, no. 6 (January 1993): 173–83. Carl Dauterman, “Dream Pictures of Cathay: Chinoiserie on Restoration Silver,” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 23, no. 1 (summer 1964): 11–25. Both Grigsby and Dauterman focus on the connections between English objects and one specific book: Nieuhof’s Embassy from the East-India Company. This volume is discussed in greater detail below. Dauterman also speculates about connections between early chinoiserie and the theater.

Johan Nieuhof, An Embassy from the East-India Company, of the United Provinces, to the Grand Tartar Cham, Emperor of China . . . , translated by John Ogilby, 2nd ed. (London, 1673). This volume was originally published in Dutch in 1665.

Dampier, New Voyage, p. 275. For the reception of Dampier in London, see Diane Preston and Michael Preston, A Pirate of Exquisite Mind: The Life of William Dampier (New York: Walker and Company, 2004), p. 242; in Boston, see “From the Magazine,” Boston Gazette, September 11–18, 1738.

Dampier, New Voyage, p. 275.

Ibid., p. 309. This is also true of the two figures below the waist molding that are not shown in this illustration.

One also wonders if the japanner was familiar with Asian handscrolls, since the continuous structure and proportions of the bands of imagery on the high chest evoke these objects.

Dampier, New Voyage, p. 275. Heckscher discusses the mirror illustrated in figure 11 in American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, p. 328. For a similar coastline, see the boat placed centrally on the London cabinet-on-stand illustrated in Huth, Lacquer of the West, pl. 55.

Dampier, New Voyage, p. 3. Daniel Defoe, The Compleat English Gentleman (London: D. Nutt, 1890), p. 225.

Parker and Stalker, Treatise, pp. 50, 40–42. For other japanned pieces that appear to present sea narratives, see the objects illustrated in David Dewey, The Geffrey Museum: A Brief Guide (London: Geffrey Museum Trust, 1998), p. 16; Fales, “Boston Japanned Furniture,” pp. 55, 58; Flanigan, American Furniture from the Kaufman Collection, p. 50; Heckscher, American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum, p. 238; Honour, Chinoiserie, pls. 30 and 31; Huth, Lacquer of the West, pls. 55, 59, 60, 90, 92; Brock Jobe and Myrna Kaye, New England Furniture: The Colonial Era (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1984), p. 197; and Richards and Evans, New England Furniture at Winterthur, pp. 305–7. As these illustrations suggest, and as mentioned in note 2, in the case of cabinets, the narrative images appear on the cabinet’s interior drawers, behind the doors.

Cherub heads also have a precedent in furniture design in that similar heads occasionally appear in the carved stands of English lacquered cabinets. See Bowett, English Furniture, p. 156. The connections between the Pickman chest and the printed page support the chest’s attribution to Thomas Johnston. Johnston had an established connection to the Boston book industry. He engraved trade cards for Boston bookseller Thomas Hancock and Boston bookbinder Andrew Barclay that feature cherub heads above lines of text. The trade cards are illustrated in Sinclair Hitchings, “Thomas Johnston,” in Boston Prints and Printmakers, edited by Walter Whitehill (Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1973), pp. 86, 118–19. There are also established connections between the bookmaking and japanning industries in London. John Baskerville, the important Birmingham type founder, trained as a japanner early in his career, in the 1720s. John Dreyfus, “The Baskerville Punches, 1750–1950,” in Dreyfus, Into Print: Selected Writings on Printing History, Typography and Book Production (London: British Library, 1994), p. 13. The author thanks David Raizman for this reference. In addition to its front, the sides of the high chest also emphasize the surface’s storytelling function. They loosely resemble bookbindings and therefore evoke a part of another material object that presents stories. As noted earlier, the two sides of the high chest feature identical images of a house and tree placed within painted rectangular frames. While this composition has parallels in Asian lacquerware, it also resembles high-style eighteenth-century bindings, which often include similar ornamental “centerpieces,” set, as their name suggests, in the center of rectangular frames. For a specific binding that the sides of the high chest resemble, see David Pearson, English Bookbinding Styles, 1450–1800 (New Castle, Del.: Oak Knoll, 2005), p. 74, fig. 3.75. Insofar as the front of the high chest resembles a printed page and the two sides loosely resemble bindings, the entire object could be said to represent a book, with its two covers opened to reveal a page of text.

Mitchell, “A Passion for the Exotic,” p. 82. For another recent work that connects chinoiserie with women, see David Porter, “Monstrous Beauty: Eighteenth-Century Fashion and the Aesthetics of the Chinese Taste,” Eighteenth Century Studies 35 (2002): 395–411. Pope and Shaftesbury, as quoted in Honour, Chinoiserie, p. 81. The Fridsberg painting is illustrated in Peter Thornton, Authentic Décor: The Domestic Interior, 1620–1920 (London: Seven Dials, 2000), p. 128.

On women and reading, see John Brewer, The Pleasures of the Imagination: English Culture in the Eighteenth Century (New York: Harper Collins, 1997), p. 193. On women as the creators of narrative objects, see Brooks, English Embroideries in the Ashmolean Museum, p. 12.

David Hancock, Citizens of the World: London Merchants and the Integration of the British Atlantic Community (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), p. 41. Pickman came from a family of ship captains and he himself traveled to Canada during the period when he owned the high chest (Phillips, History of Salem, p. 210). For the merchants’ use of coastline maps, see Hancock, Citizens of the World, p. 34. Historian Catherine Delano-Smith has also discussed the way that cartographers made maps for merchant companies such as the East India Company; see Catherine Delano-Smith, English Maps: A History (London: British Library, 1999), p. 156.

Daniel Defoe, Robinson Crusoe (1731; reprint, New York: Tor, 1989), p. 5. Jonathan Swift, Gulliver’s Travels (1726; reprint, New York: Putnam, 1999), p. 74. George Lillo, The London Merchant (1731; reprint, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press), pp. 24, 34. Swift, Gulliver’s Travels, p. 87. The connections between Lilliput and the japanned coast are more than a matter of scale. The Lilliputians also look like the japanned figures: their dress is “plain and simple, and the fashion of it between the Asiatic and the European; but he had on his head a light helmet of gold adorned with jewels, and a plume on the crest. . . . The ladies and courtiers were all most magnificently clad, so that the spot they stood upon seemed to resemble a petticoat spread on the ground, embroidered with figures of gold and silver,” pp. 19–20 (my emphasis). This connection is not coincidental: Swift owned a japanned cabinet. The fact that he wrote a story about discovery that concerns figures like the ones on this cabinet buttresses my readings of the japanned narrative and generally opens up new possibilities for thinking about the role of furniture in Gulliver’s Travels. For Swift’s cabinet, see Victoria Glendinning, Jonathan Swift (London: Hutchinson, 1998), p. 138.

The Pleasant and Profitable Companion: Being a Collection of Ingenious and Diverting Historys; With Suitable Applications or Morals for Instructing the Mind, and Encouraging Virtue (Boston, 1733), p. 137.

Edward Hatton, The Merchant’s Magazine, or, Trades-man’s Treasury, 9th impression, corrected and improved (London, 1734), preface. Lewes Roberts, The Merchant’s Map of Commerce (London, 1700), pp. 40–45. Jonathan Swift, “The Lady’s Dressing Room” (1730), in Norton Anthology of Poetry, edited by Alexander Allison and Blake Herbert, 3rd ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1983), p. 396.

Roberts, Merchant’s Map, p. 43. Historian Joyce Appleby discusses the need for this kind of conversion in Economic Thought and Ideology in Seventeenth Century England (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977), p. 201.

In the longer discussion of japanned furniture that I present in my dissertation, I argue that the way that japanning made furniture into something to explore or know had more than just an instructional purpose. It also radically changed the position that furniture maintained relative to its owner. In the seventeenth century and earlier, Anglo-Americans conceived of furniture as an almost sentient entity that, though material, possessed certain subject capacities over and above its materiality, including the capacity to know and understand like a person. Japanning, by making furniture something to be known, reversed this traditional position, making furniture an object rather than a subject. This shift is symptomatic of the new Cartesian conception of the object that emerged in the early eighteenth century. See Ethan Lasser, “Figures in the Grain: The Enlightenment of Anglo-American Furniture, 1660–1800” (Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 2007). For furniture exports from London, see Bowett, English Furniture, p. 31. For furniture exports from London to Boston specifically, see Jobe and Kaye, New England Furniture, p. 19. For furniture exported from Boston, see Leigh Keno, “‘The Very Pink of the Mode’: Boston Georgian Chairs, Their Export and Their Influence,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1996), pp. 266–306.