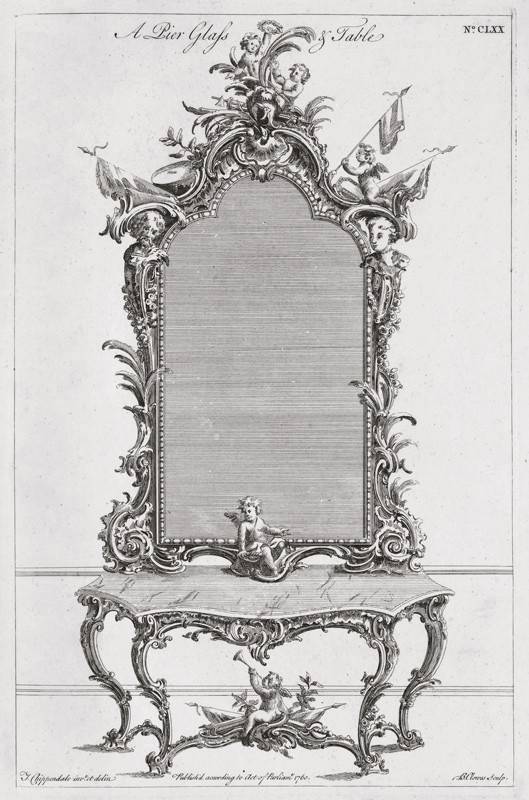

Plate 170 in the third edition of Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1762). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) This plate does not appear in the 1754 and 1755 editions.

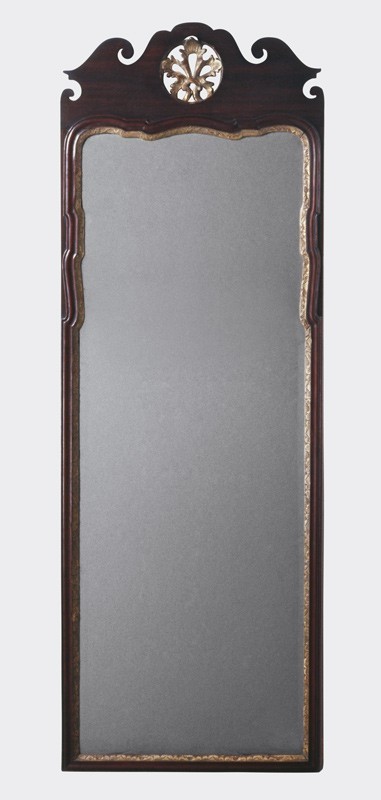

Looking glass bearing the label of John Elliott, England, ca. 1765. Mahogany with spruce and scots pine. 57" x 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The label on this looking glass is in English and German.

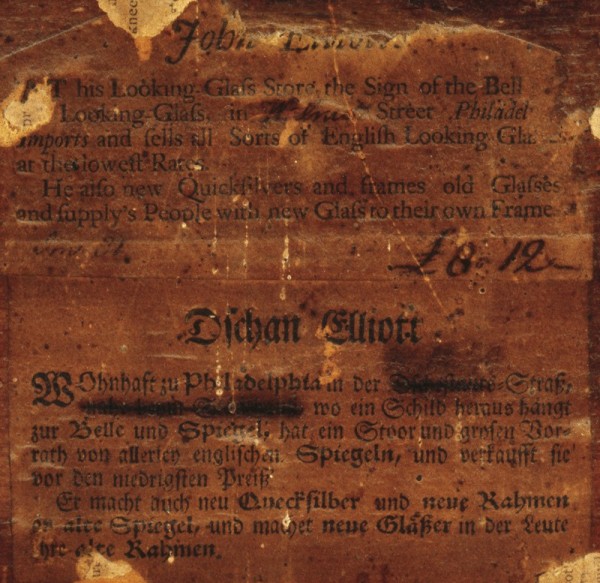

Looking glass bearing the label of John Elliott, England, ca. 1765. Mahogany with spruce and scots pine. 57" x 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The label on this looking glass is in English and German.

John Singleton Copley, Ezekiel Goldthwait, Boston, Massachusetts, 1771. Oil on canvas, 50 1/8" x 40". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, bequest of John T. Bowen in memory of Eliza M. Bowen.) The frame is attributed to Boston carver John Welch.

Detail of the carving on the frame illustrated in fig. 3.

Looking glass attributed to John Welch, Boston, Massachusetts, 1775–1790. Mahogany and white pine (gilded components) with white pine. 43 1/2" x 19 1/2". (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

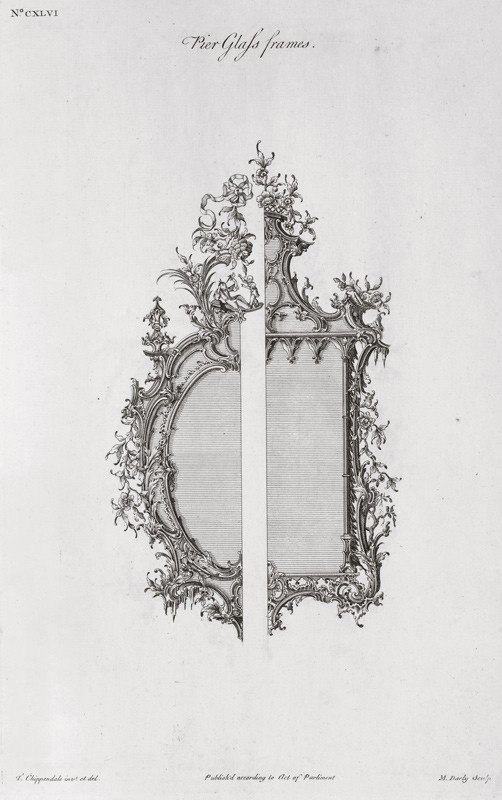

Plate 146 in the first and second editions of Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754, 1755). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Desk-and-bookcase, Boston, Massachusetts, 1770–1790. Mahogany with cherry and white pine. H. 98 1/2", W. 47 1/4", D. 24 3/4". (Courtesy, Historic New England, gift of Elizabeth Inches Chamberlain in memory of her father, Henderson Inches; photo, Richard Cheek.)

Detail of the bird ornament on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 7.

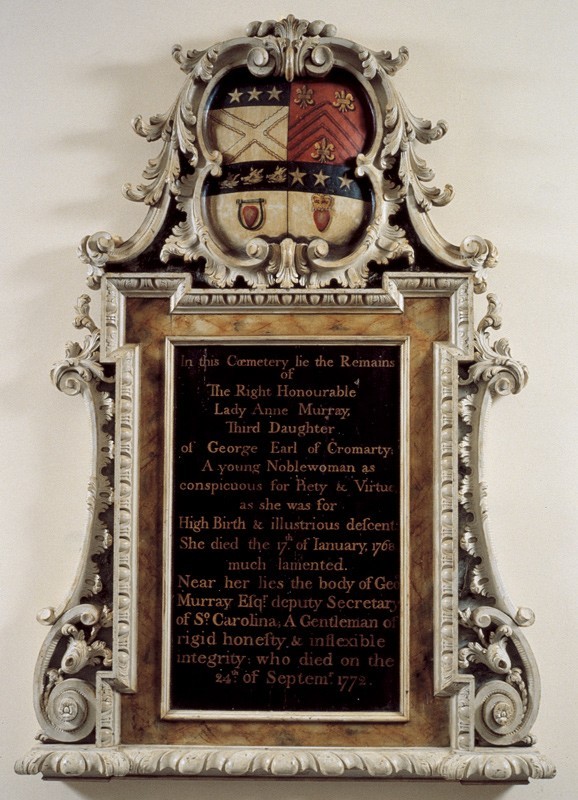

Memorial to Lady Anne Murray, attributed to John Lord, Charleston, South Carolina, 1768–1772. White pine. 73 1/2" x 51 1/4". (Courtesy, First Scots Presbyterian Church; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) As is the case with this memorial, some eighteenth-century looking glasses were painted in imitation of stone.

Looking glass attributed to John Pollard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770–1780. Mahogany with white pine. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Comparative illustration showing (left) the garland on the right side of the looking glass illustrated in fig. 10, (right) a garland from the parlor of the Thomas Ringgold House in Chestertown, Maryland. (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.) All of the carving in the Ringgold House is attributed to John Pollard. Eighteenth-century patrons occasionally commissioned the same tradesman to furnish both furniture and architectural carving. Although there is no evidence that Thomas Ringgold owned this looking glass, its garlands and those in his house show how harmonious the visual interplay between furniture and architectural carving could have been.

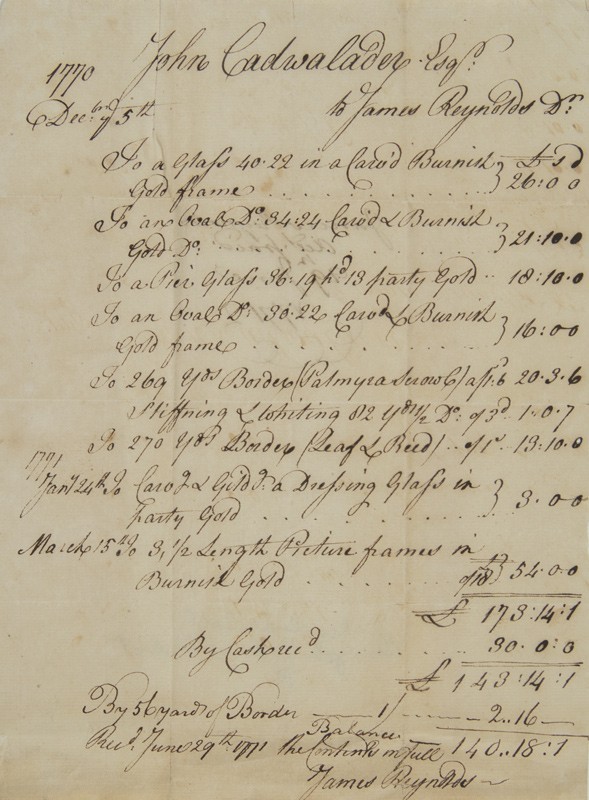

Bill from James Reynolds to John Cadwalader for work performed between December 5, 1770, and March 15, 1771. (Courtesy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.)

Pier glass attributed to the shop of James Reynolds, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770–1771. White pine with tulip poplar. 55 1/2" x 28 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail of the iron armature on the back of the pier glass illustrated in fig. 13.

Detail of the upper left corner of the pier glass illustrated in fig. 13. Reynolds applied three coats of relatively coarse gesso to the frame. The entire gesso zone is off-white in color with a gradation from dark to light. This may indicate a reduction in the percentage of glue used in the second and third coats.

Pier glass attributed to the shop of James Reynolds, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1766–1775. White pine. 60 1/2" x 30 1/4". (Courtesy, Cliveden, a co-stewardship property of the National Trust for Historic Preservation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The sides of the Fisher and Cadwalader frames appear to have been laid out with the same pattern (figs. 13, 16, 17).

Comparative illustrations showing, from left to right, the lower right corner of the pier glass illustrated in fig. 13 and the lower right corner of the pier glass illustrated in fig. 16. Patterns typically transferred only the basic outlines of carved detail, which accounts for variations within and between these looking glass frames. After laying out the carving on one side, Reynolds simply flipped the pattern to lay out the other side.

Pier glass attributed to the shop of James Reynolds, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1766–1775. White pine. 48" x 26". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Pier glass attributed to the shop of James Reynolds, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, probably 1772. White pine. 78" x 42". (Courtesy, Cliveden, a co-stewardship property of the National Trust for Historic Preservation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This glass is one of a pair.

Girandole attributed to the shop of James Reynolds, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, probably 1772. White pine. 38 1/2" x 23 1/4". (Courtesy, Cliveden, a co-stewardship property of the National Trust for Historic Preservation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The branches are missing. Their original place of attachment corresponds with the oval element above the opposing C-scrolls at the bottom of the frame.

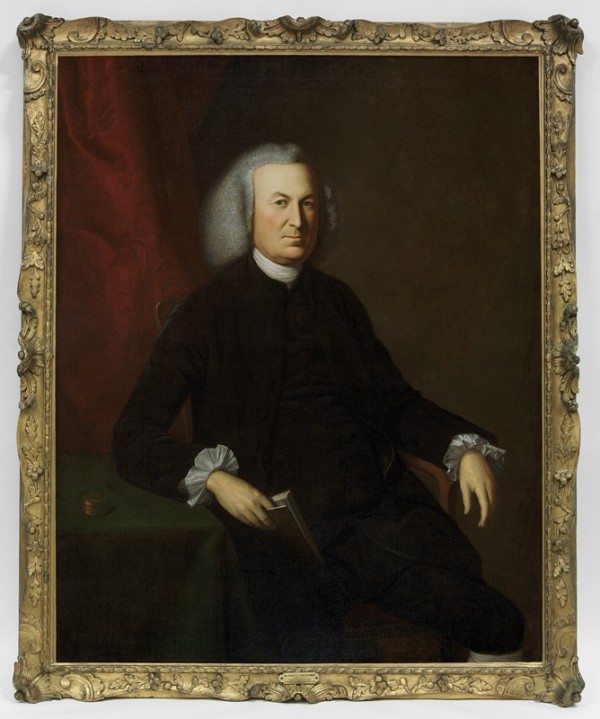

Charles Willson Peale, Thomas Cadwalader, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770. Oil on canvas. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; purchased for the Cadwalader Collection with funds contributed by the Mabel Pew Myrin Trust and the gift of an anonymous donor, 1983.) The frame is attributed to the shop of James Reynolds and measures approximately 60" x 50". All four sides have had their outer edges altered. This example is one of the three “1/2 Length Picture frames in Burnish Gold” listed in the bill illustrated in fig. 12.

Charles Willson Peale, Hannah Cadwalader, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770. Oil on canvas. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; purchased for the Cadwalader Collection with funds contributed by the Mabel Pew Myrin Trust and the gift of an anonymous donor, 1983.) The frame is attributed to the shop of James Reynolds and measures approximately 60" x 50". All four sides have had their outer edges altered. This example is one of the three “1/2 Length Picture frames in Burnish Gold” listed in the bill illustrated in fig. 12.

Charles Willson Peale, Lambert Cadwalader, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770. Oil on canvas. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; purchased for the Cadwalader Collection with funds contributed by the Mabel Pew Myrin Trust and the gift of an anonymous donor, 1983.) The frame is attributed to the shop of James Reynolds and measures approximately 60" x 50". All four sides have had their outer edges altered. This example is one of the three “1/2 Length Picture frames in Burnish Gold” listed in the bill illustrated in fig. 12.

Charles Willson Peale, The John Cadwalader Family, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1771. Oil on canvas. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; purchased for the Cadwalader Collection with funds contributed by the Mabel Pew Myrin Trust and the gift of an anonymous donor, 1983.) The frame is attributed to the shop of James Reynolds and measures approximately 60" x 50". All four sides have had their outer edges altered.

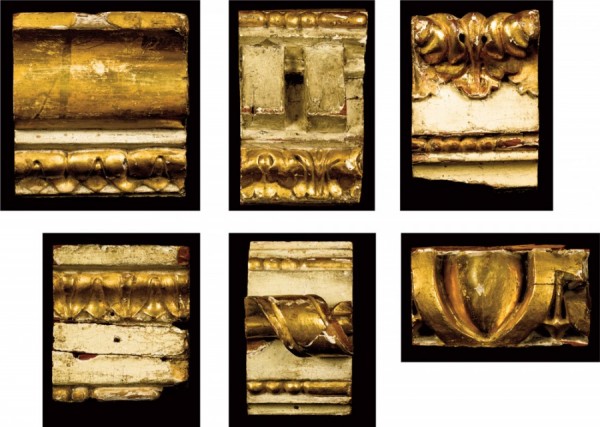

Molding sections, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1775. White pine. (Courtesy, Powell House; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The moldings at the upper left and center are cornice sections. The molding at the upper right appears to be the lower element of a chair rail. The molding at the bottom center may be a picture slip or a section of an architrave surround.

Card table attributed to Thomas Affleck with carving attributed to the shop of James Reynolds, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1771. Mahogany with yellow pine, white oak, and tulip poplar. H. 28", W. 39 1/2", D. 19 1/4". (Courtesy, Dietrich American Foundation; photo, Will Brown.) Either this table or its mate is depicted in Charles Willson Peale’s portrait The John Cadwalader Family illustrated in fig. 24.

Details showing the cabachon and acanthus on the pier glass illustrated in fig. 13.

Details showing the cabachon and acanthus on the front rail of the card table illustrated in fig. 26.

Details showing the acanthus in the upper left corner of the pier glass illustrated in fig. 13.

Details showing the acanthus on the front rail of the card table illustrated in fig. 26.

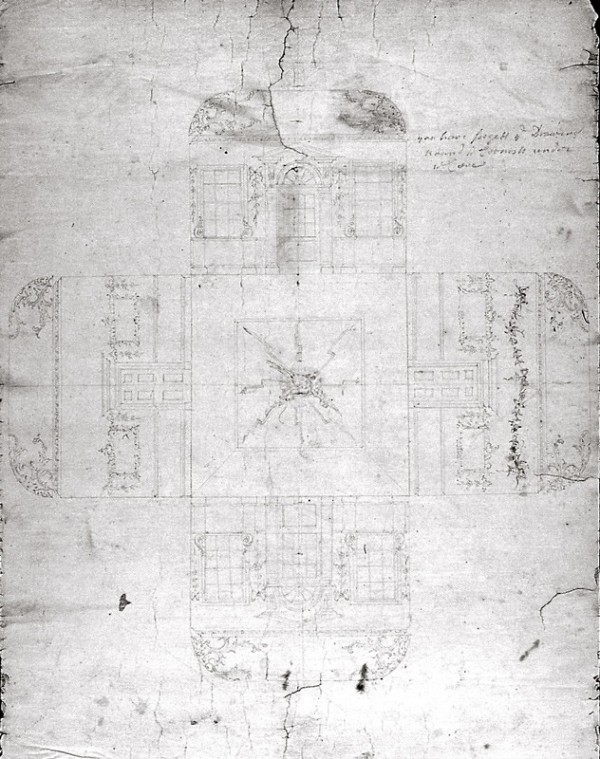

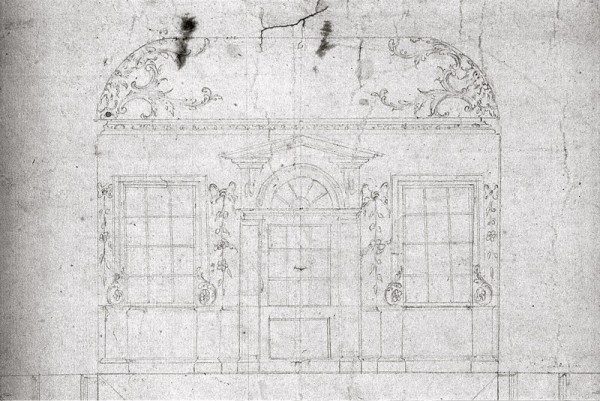

A Draft of Ornaments for the Hall at Whitehall, Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1765. Pencil on paper. Dimensions not recorded. (Photo, Luke Beckerdite.)

A Draft of Ornaments for the Hall at Whitehall, Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1765. Pencil on paper. Dimensions not recorded. (Photo, Luke Beckerdite.)

Detail of a mask representing one of the four winds in the great hall of Whitehall, Anne Arundel County, Maryland, 1765–1770. White pine. Dimensions not recorded. (Photo, Luke Beckerdite.)

Detail of a garland in the hall of Whitehall, Anne Arundel County, Maryland, 1765–1770. White pine. Dimensions not recorded. (Photo, Luke Beckerdite.)

In describing his designs for the pier glass and table illustrated in plate 170 in the third edition of The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1762), Thomas Chippendale noted that they would allow a skillful carver to “give full scope to his capacity” (fig. 1). During the eighteenth century, few furniture forms were more suited to a display of the carver’s art or more essential for an elegant interior than looking glasses. In the colonies, chimney glasses, pier glasses, and girandoles were imported from England in vast numbers and sold by merchants, cabinetmakers, upholsterers, and carvers. Although surviving bills, receipts, and advertisements by colonial tradesmen indicate that they were able to produce ornate carved looking glasses, fewer than a dozen examples in the rococo style have been identified.[1]

With their heavy glass and fragile frames, looking glasses were easily damaged or destroyed. Virginia planter William Byrd reported on an unusual incident after visiting the home of Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spotswood in 1732:

I was carried into a room elegantly set off with pier glasses, the largest of which soon came to an odd misfortune. Amongst the favorite animals that cheered . . . [Mrs. Spotswood’s] solitude, a brace of tame deer ran familiarly around the house, and one of them came to stare at me as a stranger, but, unluckily spying his own figure in the glass, he made a spring over the tea table that stood under it and shattered the glass to pieces and, falling back upon the tea table, made a terrible fracas among the china.

Although Byrd noted that Mrs. Spotswood accepted the mishap with “good humour,” the pier glass would have been very costly to replace. Even with elaborate carved and gilded looking glasses, the mirror was typically more expensive than the frame. The best crown glass used to glaze furniture, lanterns, and windows was not suitable for looking glasses. Being blown and swirled into circular sheets, it was too irregular and thin to withstand the grinding and polishing required for a smooth, reflective surface. Plate glass made by the broad process was widely used for mirrors; however, the finest glass was made in sheets cast directly from the glass furnace. Chippendale evidently imported most of his sheet glass from France. On a tour of Chippendale and Haig’s shop in 1775, Thomas Mouat was shown three French plate looking glasses 9 1/2 feet long and 5 feet 10 inches wide, which were valued at £450 each.[2]

American merchants and tradesmen had access to both types of glass. John Francis Delorme, a Charleston upholsterer, advertised French looking glasses with and without frames in sizes as large as 80 by 63 inches. Although French sheet glass was available to American artisans, most colonial looking glass makers appear to have used Vauxhall plate. In November 1773 Charleston, South Carolina, carver John Lord offered his patrons “a large assortment of The Best Vauxhall Plates for square and oval Pier Glasses” as well as an assortment of the “most fashionable Pier Frames, Gerandoles, . . . [and] Picture Frames.” Like Lord, most colonial carvers supplemented their income through the sale of imported looking glasses. Philadelphia cabinetmaker John Elliott imported large numbers of looking glasses with simple scrolled frames to which he attached labels that often were printed in German, English, or both (fig. 2).[3]

Most of the silvering, diamond cutting, and polishing advertised by colonial carvers and looking glass makers appears to have been for repair rather than manufacture. Those tradesmen who endeavored to make mirrored glass probably had difficulty competing with inexpensive imports. In 1767 Boston japanner Stephen Whiting complained that he did more “towards manufacturing Looking-Glasses than any one in the Province, or perhaps on the Continent, and would be glad of encouragement enough to think it worth while to live.”[4]

For much of his career, Whiting was associated with Boston carver John Welch. Born in that city in 1711, Welch may have received his training in the shop of George Robinson, a prominent carver and acquaintance of Welch’s father. Welch attained journeyman status by March 1732, when he was described as a carver in a summons to the Suffolk County Court of Common Pleas. He received numerous important commissions for ship and architectural carving, but his most important patron may have been artist John Singleton Copley. At least thirty-two Copley portraits are surrounded by frames that were carved by Welch (figs. 3, 4).[5]

The only looking glass associated with Welch is an oval example that reputedly descended through six generations of his family and may be the “1 mahogany frame glass” valued at £2.2 in his 1789 probate inventory (fig. 5). Like the portrait frames documented and attributed to Welch, the looking glass is decorated with bold, but relatively simple, scroll and leaf carving. The near absence of shading cuts in his work may reflect Welch’s background in ship carving, where large ornaments were viewed from a distance and did not require minute detail.

Although oval looking glasses are generally interpreted as neoclassical, they were clearly in vogue by the mid-1750s. Chippendale included designs for three oval pier glasses in the first edition of The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754) (fig. 6). Welch’s looking glass probably dates from the 1770s or 1780s, based on relationships between its bird ornament and those on Boston desk-and-bookcases from that period (figs. 7, 8).[6]

Welch appears to have relied on Whiting for gilding most of his carved frames. While in New York in 1771, Copley wrote his stepbrother Henry Pelham: “I have parted with two small frames . . . let me know what you paid Welch for carving and Whiting for Gilding.” This unusual separation of the carving and gilding trades was largely confined to New England, where ship carvers and cabinetmakers established the practice of subcontracting gilding and decorative painting to japanners during the first quarter of the eighteenth century.[7]

In contrast, carvers from other colonial cities followed British practice in gilding and painting their frames. In the December 7, 1765, issue of the New-York Gazette or the General Advertiser, James Strachan reported that he made “all Sorts of Picture and Glass frames . . . carved and gilt, in Oil or Burnished Gold.” The following year John Lord offered “An assortment of Glasses with carved frames to be sold cheap . . . [along with] all kinds of work new gilt.” No looking glasses by either man are known, but Strachan provided six carved and gilded picture frames for portraits of James Beekman’s family, and Lord was probably the maker of a monumental memorial to Lady Anne Murray of Charleston (fig. 9). The quality of the carving on these objects seems to confirm the London training that both men claimed to have received.[8]

Although dozens of tradesmen advertised the manufacture of carved looking glass frames, Philadelphia carvers were responsible for nearly all of the surviving examples in the rococo style. Of those, one is attributed to John Pollard (figs. 10, 11), and five to James Reynolds. A London-trained carver, Reynolds arrived in Philadelphia on the brig Mary and Elizabeth in August 1766. The next month he advertised “all the various Branches of Carving and Gilding in the newest . . . Taste, such as . . . House Work, Chair and Cabinet Ditto, Glass and Picture Frames, Slab and Table Ditto, Girandoles, Chandiliers . . . and Ship Work in general.” Subsequent notices

indicate that Reynolds also sold imported looking glasses, gilding and painting supplies, and papier-mâché moldings, as did many of his contemporaries in the carving trade.[9]

Reynolds enjoyed the patronage of a number of prominent Philadelphians including merchant John Cadwalader, Pennsylvania Chief Justice Benjamin Chew, and Governor John Penn. In June 1771 Cadwalader paid Reynolds £140.18.1 for four large carved looking glasses, 539 yards of papier-mâché molding, a dressing glass, and three half-length picture frames in burnished gold. The carver’s bill specified the basic shape of the frames, their glass dimensions, and their finish (fig. 12).[10]

A large rococo pier glass that descended in the John Cadwalader family appears to be the “party gold,” or parcel-gilt, example listed in Reynolds’s bill (fig. 13). Reynolds used a frame saw to size the stock for the top, bottom, and sides. After planing the rabbet for the glass, he cut the rough profile of the Chinese pilasters, rock outcroppings, scrolls, and naturalistic elements with a bow saw, then used chisels and gouges to establish the final outlines. Reynolds probably screwed the frame sections to boards before starting the carving, since that would have been the most effective way to hold long work pieces in place. Alternatively, he could have secured the frame sections to the bench with either clamps or holdfasts. Like all carvers, Reynolds glued up his stock where additional thickness was required. That procedure saved both time and materials. After completing the carving, Reynolds assembled the frame, gluing together the corners and reinforcing each butt joint with an iron armature (fig. 14). Last, he screwed a wood brace to the center of the top section to prevent it from bowing. British looking glasses often have metal or wood supports in similar positions.

The basic carving and surface treatment of the Cadwalader pier glass are consistent with contemporary British work. All of the shading cuts are in the wood rather than in the gesso. Recutting was limited to areas where the gesso was too thick and obscured the carved detail. A mixture of hide glue and chalk, the gesso on most rococo frames was intended to fill the pores of the wood and produce a smooth, homogenous surface for the bole and gold leaf rather than function as a substrate for carving. To protect the gilding, Reynolds applied a coat of varnish. Microscopy reveals that the varnish covered both gilded and ungilded areas, indicating that the frame was originally parcel-gilt, as described in the bill to Cadwalader (fig. 15). A closely related pier glass that reputedly descended in the Fisher family of Philadelphia may also have had a parcel-gilt surface (fig. 16). More important, its sides appear to have been laid out with the same pattern used for the Cadwalader example (fig. 17).[11]

During the last half of the eighteenth century, painted frames were a less expensive alternative to those with burnished gold or parcel-gilt surfaces. On October 4, 1771, Reynolds billed Cadwalader £11.15 for “a glass 36:19 in a Carv’d white frame.” That was nearly £7 less than the parcel-gilt pier glass of comparable size listed in the carver’s earlier bill. Cadwalader’s white pier glass may have resembled one reputedly made for Richard Edwards, first owner of Taunton Iron Works in Taunton, New Jersey (fig. 18). Like the surviving Cadwalader glass (fig. 13), the Edwards example has butt-joined corners secured with glue and an iron armature. There are minor variations in the design of the carved elements on these frames, but they were clearly executed by the same hand. On both glasses, the C-scrolls in the upper corners have small clusters of acanthus leaves that were shaded with flutes made perpendicular to their natural flow. Other similarities can be noted in the modeling of the scroll volutes and the outlining and shading of the leaves in the garlands. On the Edwards frame, white lead paint and a resin varnish were used to produce a cream-colored surface. The specific composition of the varnish is not known; however, eighteenth-century carvers and gilders frequently used a hard “white varnish” to protect gilt or painted surfaces. White varnishes were usually made of spirits of wine, turpentine, white resin, and one or more gums, and they could be tinted to make exposed gesso surfaces resemble stone.[12]

Two large pier glasses and a girandole that descended in the Chew family of Cliveden appear to have been painted white and varnished like the Edwards glass (figs. 19, 20). On April 20, 1772, Chief Justice Benjamin Chew paid Reynolds £51.19 “in full of (his) . . . Account &. all Dues and Demands.” That amount would have been sufficient for a pair of large pier glasses and a pair of girandoles. The pier glasses are undoubtedly from Reynolds’s shop. Both have butt-joined frames that are glued and reinforced with iron brackets and carved details matching those on the Cadwalader, Fisher, and Edwards pier glasses. Because of their greater size, the Chew examples have two mirrored plates. The carved, horizontal cross brace is dovetailed from the back and serves two purposes: it traps and supports the mirrored plates and prevents the sides from bowing under the considerable weight of the glass.[13]

In his Blue Book of Philadelphia Furniture, William Macpherson Hornor speculated that Chew may have acquired the pier glasses and girandole from the estate of John Penn Sr. Although none of the glasses described in the May 15, 1788, inventory of Penn’s estate matches the Chew examples, Penn was one of Reynolds’s most important patrons. On October 27, 1774, Penn paid the carver £139.12 for “Sundry Articles,” which were probably looking glasses. Fifteen looking glasses were listed in Penn’s inventory. Seven parcel-gilt girandoles, an “elegant oval looking glass in a white and gold frame,” and a “similar frame, the glass of which has been broken” hung in the dining room. The front parlor contained a “large oval pier looking glass,” and the “Back Chamber,” or bedroom, had a “large oval looking glass in a gilt frame and a swinging glass in a mahogany frame.” The remaining looking glasses hung in the “Front Chamber,” or bedroom. These objects were described as “a large looking glass in a gilt frame” and an “elegant small glass in a white frame.”[14]

Cadwalader’s inventories and accounts reveal even more about the display of looking glasses in eighteenth-century America. According to inventories taken in 1786, one “large gilded looking glass” and five “family pictures” (figs. 21-24) hung in the front parlor on the first floor. The gold surfaces of the looking glass and picture frames undoubtedly provided a striking contrast with the blue walls, blue Wilton carpet, and blue silk damask curtains and upholstery fabrics in that room. A similarly uniform color arrangement was found in the rear parlor, which had a “gold frame oval looking glass,” yellow walls, and yellow silk upholstery and curtains. The upper floors of Cadwalader’s house were painted green. On the second storey a “large white & gold looking glass” hung in the front chamber and a gilt looking glass hung in the rear. A single “white frame looking glass” was on a wall on the third storey.[15]

Although Cadwalader’s interiors were unusually elaborate by colonial standards, there is extensive evidence of similar furnishing schemes in Britain. Sir Rowland Winn’s accounts with Chippendale for furniture and interior decorations for Nostell Priory provide a contemporary comparison. According to the “list of furniture for different Appartments” prepared by Chippendale in 1767, the dressing rooms and antechambers adjacent to the bedrooms were hung with green, blue, crimson, and yellow flock wallpapers. The antechamber next to Sir Rowland’s bedroom was hung with a “blew verditure paper and a small Gooderoon border gilt in burnished gold” and furnished with forty-one burnished gold picture frames, an elaborate oval looking glass with “Mouldings and Ornamental parts gilt in burnish gold,” and an overmantel picture of Cleopatra in a carved and gilded frame.[16]

In England and her colonies, gilded borders and moldings were used to provide visual continuity between looking glasses, picture frames, and interior architectural details. Papier-mâché borders were less expensive than carved moldings and were often gilded. Cadwalader’s house had a variety of them. Painter and glazier Anthony DeNormandie charged him £13.2 for “laying gold on 786 feet [of] Paper Mache” in November 1770. The following month Cadwalader ordered two different patterns from Reynolds. Described as “Palmyra Scrowl” and “Leaf &. Reed,” they were apparently installed the following October, when the carver charged Cadwalader £1.10 for “putting up the Borders in [the] Chamber” and 15s. for two pounds of brass pins. The pins were used to blend in with the gold leaf and avoid discoloration, which would have resulted had Reynolds used iron nails.[17]

Like many elaborate British houses of the period, Cadwalader’s interiors had gilt architectural carving. The carving, which was produced by three different shops at a cost of more than £362, included sculptural appliqués, tablets, festoons, flowers, trusses, and a variety of carved moldings. Hercules Courtenay, the carver responsible for much of the sculptural work, received £12.13 for “27 Books of Gold laid on (the) cornice.”[18]

Although Cadwalader’s house was demolished in the late nineteenth century, several fragments of gilded moldings from an unidentified Philadelphia town house allow one to visualize to some degree how his rooms may have appeared (fig. 25). On these fragments, the dentils, fascia, and uncarved moldings of the cornice sections are painted cream white and the carved elements are gilded. Each molding has four thin, but distinct, gesso layers: a white ground covered successively by gray, yellow-white, and gray-white coats. On the cornice and carved band molding, an ochre bole was used to give the gold a warm, reflective quality. Elsewhere red bole and burnished gold were used to produce a surface with greater depth and richness. If these fragments came from the same room, there would have been obvious tonal variation in the gilding.

The precise architectural context of these fragments is difficult to determine. However, it appears that the acanthus-carved cyma was the lower element of a chair rail and the banded half-round molding was a picture slip (fig. 25). Picture slips were attached to the wall below the cornice and used for hanging paintings, prints, and looking glasses. Although the bills for architectural carving in Cadwalader’s residence did not specifically mention a picture slip, references were made to several moldings that could have served that purpose.

The looking glasses and family portraits in Cadwalader’s main parlors were part of an extensive furnishing scheme that included multiple suites of furniture with carving by Reynolds and other tradesmen who provided architectural ornaments for the house (fig. 26). Harmony and balance were achieved through corresponding details and common workmanship (figs. 11, 27). The tradesmen commissioned by Cadwalader probably submitted sketches for his approval, then created patterns to ensure that designs could be transferred from object to object.

An anonymous drawing inscribed “A Draft of Ornaments for the Hall at Whitehall” illustrates this practice in colonial America (fig. 28). It depicts the great hall of Whitehall, country residence of Maryland Royal Governor Horatio Sharpe (1718–1790). The carving includes a rococo bird taken from a design by Thomas Lightoler, masks representing the four winds (fig. 29), seventeen garlands (fig. 30), and four rectangular looking glasses. The size and shape of the looking glasses suggest that they were intended to have sofas or tables beneath them. Sharpe may taken the looking glasses with him when he returned to England in 1773, or they may have been bequeathed to his attorney John Ridout, who lived in Whitehall following the governor’s departure.[19]

Large-scale, sculptural work like that surviving in Whitehall required exceptional skill. Indeed, it is possible that Sharpe’s carver specialized in looking glasses, picture frames, pier tables, and architectural ornaments, as was common in large British shops. As the looking glasses discussed above indicate, the three-dimensionality of these forms gave carvers the ability to exploit their skills as fully as their patrons’ pockets and imaginations allowed.

Thomas Chippendale, The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (London, 1762), p. 18, pl. 170.

William Byrd II, “A Progress to the Mines,” in The London Diary (1717–1721) and Other Writings, edited by Lewis B. Wright and Marion Tinling (New York: Oxford University Press, 1958), p. 355. Christopher Gilbert, The Life and Work of Thomas Chippendale, 2 vols. (London: Studio Vista, 1978), 1: 44.

City Gazette & Daily Advertiser, January 28, 1796. South Carolina Gazette, November 8, 1773. Philip D. Zimmerman, “Early American Makers’ Marks,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Easthampton, Mass.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2007), pp. 137–38.

Boston News Letter, November 12, 1767, as quoted in The Arts and Crafts of New England, 1704–1775: Gleanings from Boston Newspapers, compiled by George Francis Dow (Topsfield, Mass.: Wayside Press, 1927), p. 129.

For more on Welch and Whiting, see Luke Beckerdite, “Carving Practices in Eighteenth-Century Boston,” in Old Time New England: New England Furniture, Essays in Memory of Benno Forman, edited by Brock Jobe (Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1987), pp. 142–48; Morrison H. Heckscher and Leslie Greene Bowman, American Rococo, 1750–1775: Elegance in Ornament (New York: Harry Abrams, 1992), pp. 137–42; and Morrison H. Hechscher, “Copley’s Picture Frames,” in Carrie Rebora, Paul Staiti, Erica Hirshler, Theodore E. Stebbins Jr., and Carol Troyen, John Singleton Copley in America (New York: Harry Abrams for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995), pp. 142–59.

Beckerdite, “Carving Practices,” pp. 138–48. A late baroque looking glass illustrated in Luke Vincent Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America, 2 vols. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1921), 1: 296, fig. 333, has a bird ornament that may be related to those attributed to Welch.

Letters and Papers of John Singleton Copley and Henry Pelham, 1739–1776, compiled by Charles Francis Adams, Gurnsey Jones, and Worthington Chauncey Ford (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society Collections, 1914), p. 166.

For more on Strachan, see Morrison Heckscher, “The Beekman Family Portraits and Their Eighteenth-Century New York Frames,” Furniture History 26 (1990): 116–17, 120; Heckscher and Bowman, American Rococo, pp. 156–48; and Luke Beckerdite, “Immigrant Carvers and the Development of the Rococo Style in New York, 1750–1770,” in America Furniture, edited by Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1996), pp. 247–48. Furniture historian John Bivins was the first to attribute the Murray memorial and several important Charleston carved interiors to Lord. For more on Lord and Charleston carving, see John Bivins, “Charleston Rococo Interiors, 1765–1775: The ‘Sommers’ Carver,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 12, no. 2 (November 1986): 1–129.

For more on Pollard, see Luke Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part III: Hercules Courtenay and His School,” Antiques 131, no. 5 (May 1987): 1052–63; Luke Beckerdite and Leroy Graves, “New Insights on John Cadwalader’s Commode-Seat Side Chairs,” in American Furniture, edited by Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2000), pp. 152–69; and Andrew Brunk, “Benjamin Randolph Revisited,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Easthampton, Mass.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2007), pp. 2–83. Pennsylvania Gazette, September 4, 1766. For more on Reynolds, see Luke Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part 1: James Reynolds,” Antiques 125, no. 5 (May 1984): 1120–33.

The “1/2 Length Picture frames in Burnish Gold” valued at £18 each were for Charles Willson Peale’s portraits of John Cadwalader’s parents and his brother Lambert. Bill from James Reynolds to John Cadwalader, payment dated June 29, 1771 (for work performed between December 5, 1770, and March 15, 1771), box 2, folder 20, General John Cadwalader Section, Cadwalader Collection, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. This bill is also reproduced in Nicholas B. Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur: The House and Furniture of General John Cadwalader (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1964), p. 46. Reynolds also made a similar frame for Peale’s group portrait of the John Cadwalader family (fig. 24).

Many British looking glasses in the late baroque style have frames that were rough modeled then coated with numerous layers of gesso to build up a dense homogenous ground for the finish cuts. Flat surfaces, such as the pediments and architraves of architectural glasses, were particularly well suited for this treatment. The furniture conservation staff of the Winterthur Museum identified the original varnish layer using fluorescence microscopy.

The furniture conservation staff of the Metropolitan Museum of Art performed fluorescence microscopy on the Edwards glass. Bill from James Reynolds to John Cadwalader, payment dated November 25, 1771 (for work that commenced by October 4), Incoming Correspondence, 1771–1772, box 3, folder 14, General John Cadwalader Section, Cadwalader Collection, Historical Society of Pennsylvania. This bill is reproduced in Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, p. 124. Boston News Letter, November 12, 1767, as quoted in Dow, comp., The Arts and Crafts of New England, p. 129. Colonial Furniture of West New Jersey, compiled by Thomas Smith Hopkins and Walter Scott Cox (Haddonfield, N.J.: Historical Society of Haddonfield, 1936), p. 51.

Raymond V. Shepherd Jr., “Cliveden and Its Philadelphia Chippendale Furniture: A Documented History,” American Art Journal 2, no. 2 (November 1976): 11.

William Macpherson Hornor Jr., Blue Book of Philadelphia Furniture: William Penn to George Washington (Philadelphia: privately printed, 1935), pp. 277–78. Marie G. Kimball, “The Furnishings of Governor Penn’s Town House,” Antiques 19, no. 5 (May 1931): 375–78.

Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, pp. 62–74; Beckerdite, “James Reynolds,” p. 1133 n. 26; and Beckerdite and Graves, “New Insights on John Cadwalader’s Commode-Seat Side Chairs,” pp. 160–65, 168 n. 10.

Gilbert, The Life and Work of Thomas Chippendale, 1: 180–83.

DeNormandie’s bill is reproduced in Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, p. 34. Bill from James Reynolds to John Cadwalader, November 25, 1771.

Hercules Courtenay to John Cadwalader, payment dated February 5, 1771 (for work performed in September 1770), Incoming Correspondence, Bills, and Receipts, box 2, folder 17, General John Cadwalader Section, Cadwalader Collection, Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Courtenay’s bill is reproduced in Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, p. 12.

Previous scholars attributed Whitehall to William Buckland based on the unsupported assumption that he worked in Maryland before moving there permanently in 1771 (Rosamond Randall Beirne and John Henry Scharff, William Buckland, 1734–1774: Architect of Virginia and Maryland [Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 1958], pp. 60, 69, 72, 74, 123, 135, 161). Not only does the writing on the drawing differ markedly from Buckland’s hand, but the carving is entirely different from that attributed to Buckland’s principal carvers, William Bernard Sears, who worked for Buckland from 1755 to ca. 1765, and Thomas Hall, who worked for Buckland from 1771 to 1774. For more on these artisans and Buckland’s career in America, see Luke Beckerdite, “William Buckland Reconsidered: Architectural Carving in Virginia and Maryland, 1755–1775” (master’s thesis, Wake Forest University, 1986). For information on Sharpe’s and Ridout’s residency, see Charles Scarlett Jr., “Governor Horatio Sharpe’s Whitehall,” Maryland Historical Magazine 46 (March 1951): 8–26.