Chest, Catawba County, North Carolina, 1800–1820. Yellow pine. H. 14", W. 24 1/4", D. 12". (Private collection; photo, Wesley Stewart.) This small chest was made in the Catawba Valley region of the piedmont. The façade is decorated with seven compass roses and an inscription in script. Only the first name of the owner—“Sarah”—is legible. The lid has ovolo-molded edges and wooden pintle hinges that are nailed to the back and sides of the top. The wedged dovetails and use of a center foot suggest that the maker was of Germanic descent.

Chest, Davidson County, North Carolina, 1800–1820. Yellow pine. H. 22 1/2", W. 51 3/4", D. 19 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The wedged dovetails and pinned feet and moldings suggest that the maker of this chest was trained in the Germanic tradition. The decorator probably used a rag to dab on the salmon paint and then brushed in the black background of the compass roses. No other chests with a similarly shaped central drop and foot are known.

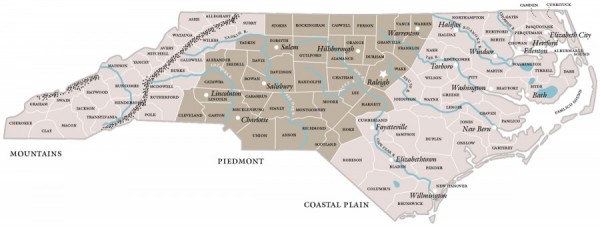

Map illustrating the eastern and western boundaries of the North Carolina piedmont, modern North Carolina counties, and major towns about 1800. (Artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

Map illustrating the major routes taken by early North Carolina settlers into the piedmont region and the major rivers along which they settled. (Adapted from a map in Catherine W. Bishir and Michael T. Southern, A Guide to the Historic Architecture of Piedmont North Carolina [Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003], p. 11; artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

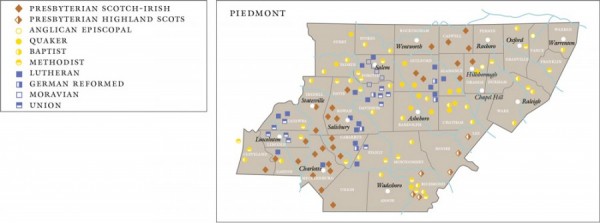

Map illustrating the ethnic settlement patterns in piedmont North Carolina as indicated by religious congregations about 1800. (Adapted from a map in Catherine W. Bishir and Michael T. Southern, A Guide to the Historic Architecture of Piedmont North Carolina [Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003], p. 12.)

John and Rachel Allen House, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1782. (Courtesy, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources.) The Allen House is representative of a typical log dwelling inhabited by early settlers in piedmont North Carolina. Until 1967 the house stood on its original site near Snow Camp but now is part of the Alamance Battleground State Historic Site.

Chest, Rowan County, North Carolina, possibly 1768. Tulip poplar with oak. H. 23", W. 50 1/2", D. 23". (Courtesy, North Carolina Museum of History; photo, Eric Blevins.)

Detail of fingerpainted tulips on the chest illustrated in fig. 7. (Photo, Eric Blevins.)

Detail of crab lock on the chest illustrated in fig. 7. (Photo, Eric Blevins.)

Latta Plantation, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, early nineteenth century. (Courtesy, Historic Latta Plantation, Huntersville, North Carolina.) Latta Plantation exemplifies the type of frame house a member of North Carolina’s emerging backcountry elite might have occupied. The home was built by James Latta, who came from Ireland in 1785 and married Jane Knox. They were part of the strong Presbyterian community in Mecklenburg County. Today Latta Plantation is a living history farm located within Latta Plantation Nature Preserve.

Chest, probably Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1820. Yellow pine. H. 26 1/4", W. 49 1/4", D. 20 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The chest has three lower drawers (the central one was never fitted with a brass pull) separated by panels with molded surrounds. The corners of each drawer front are decorated with quarter fans like those at the corners of the case above. The front edges of the case, the recessed panels separating the three lower drawers, and most of the moldings are painted in colors that contrast with the ochre background. Marks on the surface of the chest indicate that the decorator used a compass, templates, and straightedge to lay out his work.

Detail of the central panel on the chest illustrated in fig. 11. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the right panel on the chest illustrated in fig. 11. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, probably Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1820. Yellow pine. H. 26 3/4", W. 49 3/4", D. 21 1/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Unlike the chest illustrated in fig. 11, this example has two drawers separated by painted lines that simulate inlaid fluting, another possible concession to neoclassical taste

Sugar pot, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1780–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 7 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Signature of Josiah C. Foster on the underside of the lid on the chest illustrated in fig. 14. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest attributed to Daniel Anthony or Henry Anthony, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1850. Walnut with tulip poplar. H. 26 1/2", W. 49 3/8", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, North Carolina Museum of History; photo, Eric Blevins.)

Composite detail showing the drawer dovetails on the chests illustrated in figs. 11 (left) and 17 (right). (Photos, Gavin Ashworth [left] and Eric Blevins [right].)

Details of the left front feet of the chests illustrated in figs. 14 (left) and 17 (right). (Photos, Gavin Ashworth [left] and Eric Blevins [right]).

Chest, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Tulip poplar with yellow pine. H. 23 1/2", W. 43 1/2", D. 19 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) As on the chests illustrated in figs. 11 and 14, the polychrome areas of decoration are painted on a light ochre background. The base and lid moldings on this chest are painted reddish orange to contrast with the case. The lid is attached to the case with forged iron strap hinges. The case and the feet are joined with wedged dovetails, and the lid, base moldings, and feet are attached with both wooden pins and nails. The maker produced a walnut chest identical to this example, which also has a recovery history in the Kimesville area.

Detail of the left panel on the chest illustrated in fig. 20. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, Stanly County, North Carolina, 1820–1840. Yellow pine. H. 25 3/4", W. 47 1/4", D. 20". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The decorator used a round brush or wadded cloth to produce overlapping circular patterns in the salmon and blue grounds. After laying out his designs with a straightedge and compass, the decorator used the same ornamental technique to apply the white paint.

Detail of the central fylfot on the lid of the chest illustrated in fig. 22. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The decorator used a brush to apply the thin black line accentuating the lobes of the fylfots.

Chest, Cabarrus County, North Carolina, 1808–1840. Tulip poplar with yellow pine. H. 25", W. 49 5/8", D. 22 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The inner foot profile is a single cove and ovolo.

Chest, Stanly County, North Carolina, 1823–1840. Yellow pine. H. 30 1/2", W. 50 1/2", D. 24". (Collection of Elbert H. Parsons Jr.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a side of the chest illustrated in fig. 22. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet on this chest terminate with an ovolo at the top.

Detail of a side of the chest illustrated in fig. 25. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet on this chest terminate with an additional cove at the top, making them taller and broader than those illustrated in fig. 26.

Detail showing coped moldings on the chest illustrated in fig. 25. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

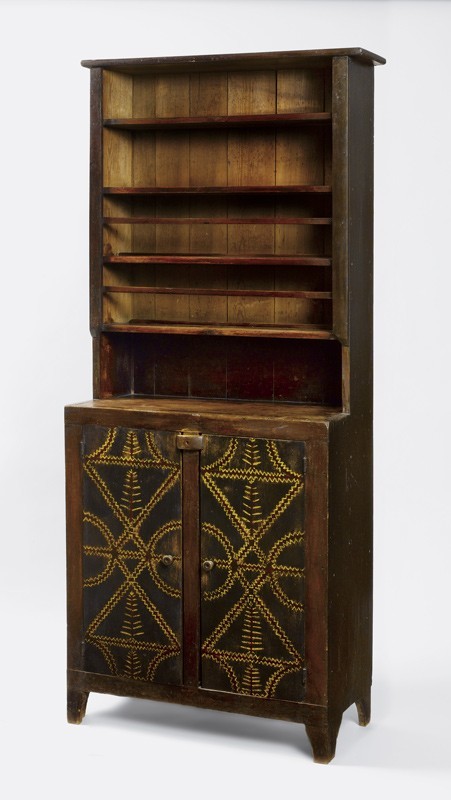

Cupboard attributed to the Jacob Sanders shop, Montgomery County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Yellow pine. H. 84 1/4", W. 50 1/4", D. 21 3/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) A front baseboard that descends to a pronounced peak is common on pieces from this group. Approximately twenty examples are known.

Detail showing the case dovetails, heavy beading, and applied ogee moldings on the cupboard illustrated in fig. 29. (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing a mitered and nailed foot joint and a strap-and-pintle hinge on the cupboard illustrated in fig. 29. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The pintle hinges allow the doors to be easily removed.

Detail of the stacked cornice and fascia on the cupboard illustrated in fig. 29. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The lunettes were laid out with a compass and then sawed.

Chest attributed to the Jacob Sanders shop, Montgomery County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Yellow pine. H. 37 1/2", W. 37 1/2", D. 21 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Fylfots and compass roses like those on this chest are the most common motifs on piedmont North Carolina furniture.

Detail of a strap-and-pintle hinge on the chest illustrated in fig. 33. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dish dresser attributed to the Jacob Sanders shop, Montgomery County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Yellow pine. H. 85", W. 50", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Craig McDougal.) This object has incurved feet like those on the dish dresser and chest illustrated in figs. 38 and 43. Like this example, most dish dressers in the group have central stiles, although not all are shaped.

Detail of the cornice decoration on the dish dresser illustrated in fig. 35.

Hanging cupboard attributed to the Jacob Sanders shop, Montgomery County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Yellow pine. H. 27 1/4", W. 18 1/2", D. 9 1/2". (Courtesy, Greensboro Historical Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Early photograph of a dish dresser with scalloped stiles similar to those on the hanging cupboard illustrated in fig. 37. (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) The crescent-shaped scallops terminate at a shelf or plate rail and are connected by a vertical rod. The stiles on this dresser were removed and discarded during the twentieth century.

Hanging cupboard attributed to the Jacob Sanders shop, Montgomery County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Yellow pine. H. 29 3/4", W. 25 1/2", D. 13". (Wilkinson Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a strap-and-pintle hinge on the door of the hanging cupboard illustrated in fig. 39. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest of drawers attributed to the Jacob Sanders shop, Montgomery County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Walnut and light wood with yellow pine. H. 52 3/4", W. 39", D. 19 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the lightwood cock-beading, lunetted fascia, and crescent inlay on the chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 41. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest attributed to the Jacob Sanders shop, Montgomery County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Yellow pine. H. 17 1/4", W. 31 1/4", D. 13 1/4". (Courtesy, Greensboro Historical Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dish dresser, Montgomery or Randolph County, North Carolina, 1820–1850. Yellow pine. H. 80 1/2", W. 61 1/2", D. 21 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This piece does not have a central stile like the four other related dressers.

Chest, Rowan County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Tulip poplar with yellow pine. H. 24", W. 49 1/4", D. 20 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Wesley Stewart.) The cream-colored paint on this chest was originally much thicker. The sides and feet are joined with wedged dovetails and the base is nailed in place. The foot is unusual in having sawtooth shaping where the bracket rises toward the base molding.

Detail of the central motif on the chest illustrated in fig. 45. (Photo, Wesley Stewart.) Although now worn, the paint used for the lobe-and-spade-shaped design may have been patterned.

Chest, Chatham County, North Carolina, 1801–1830. Yellow pine. H. 29", W. 48", D. 18". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Beneath the black ground is a red primer coat, probably applied to seal the resinous yellow pine. The chest has wedged dovetails, unusually tall bracket feet, and an applied, filleted ogee beneath its molded top.

Detail of the central motif on the chest illustrated in fig. 47. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Doubloon, Ephraim Brasher, New York, 1787. Gold. (Courtesy, American Numismatic Society.)

Touchmark of Jehiel Johnson, Fayetteville, North Carolina, 1817–1819. Pewter. (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail of the right side of the chest illustrated in fig. 47. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The case extends about one inch beyond the rear edge of the back feet, presumably to accommodate an architectural baseboard.

Chest, Chatham or Randolph County, North Carolina, 1801–1830. Yellow pine. H. 27 3/8", W. 51 1/8", D. 22 3/8". (Courtesy, High Museum of Art.)

Chest, Chatham County, North Carolina, 1840–1850. Yellow pine. H. 24 1/2", W. 41", D. 19". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the central façade decoration on the chest illustrated in fig. 53. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Three chests in this group have the owner’s initials painted in script. The circular belly of the vase and some of the leaves originally had a light pink wash, but only faint outlines and tiny fragmented areas of color remain. The upper section of the vase retains a thicker, darker coat of pink paint like that on the flowers and buds.

Detail of a rear foot on the chest illustrated in fig. 53. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, Chatham County, North Carolina, 1840–1850. Yellow pine. H. 23 1/2", W. 43 1/2", D 18 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The case and feet of this chest are joined with wedged dovetails. The rear feet do not extend beyond the back of the case, and their supports are nailed into the bottom in a conventional manner.

Chest, possibly Rutherford County, North Carolina, 1800–1850. Yellow pine. H. 26 3/4", W. 41 1/2", D. 16". (Private collection; photo, Wesley Stewart.) The decorator of this chest probably used a sponge or rag dipped in black paint to apply the arcs and dots on the façade. This object and the chest illustrated in fig. 58 are similar in form, but their construction differs. The case of the former is dovetailed, whereas the case of the latter is joined and secured with screws.

Chest, possibly Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, 1800–1850. Yellow pine. H. 30 1/4", W. 44 1/2", D. 19 7/8". (Private collection; photo, courtesy Deanne Levison.) The front and back boards are screwed to the side boards, the frame is constructed with pinned mortise-and-tenon joints, and both the case and waist molding are nailed to the frame.

Chest, Wake County, North Carolina, 1800–1820. Yellow pine. H. 24", W. 29", D. 15". (Wilkinson Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The lid has lost much of its paint, but it appears to have been blue with red edges and moldings. The front and side boards are joined with blind dovetails, the rear and side boards are joined with half-blind dovetails, and the front and side feet are joined with fully exposed dovetails. The lid battens are attached with pinned tongue-and-groove joints, and the moldings and base are secured with cut nails.

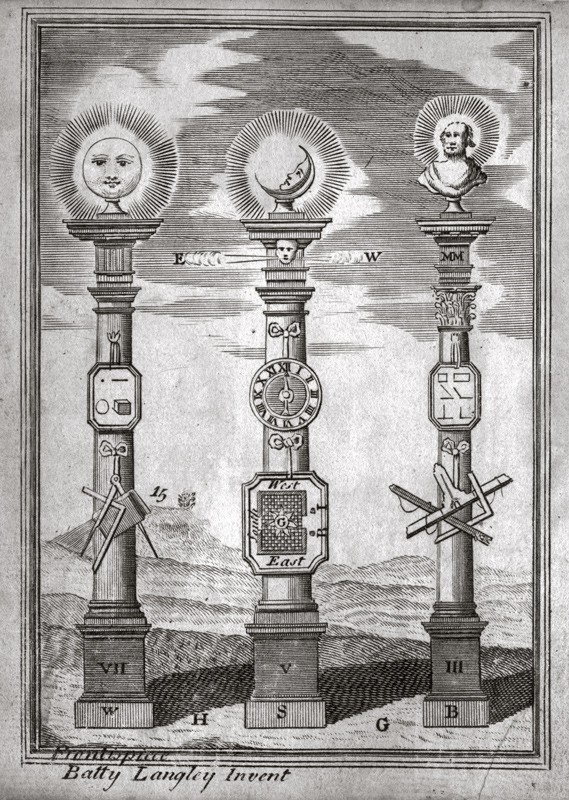

Frontispiece of B. Langley and T. Langley, The Builder’s Jewel: or the Youth’s Instructor and Workman’s Remembrancer, 12th ed. (Dublin: James Williams in Skinner-Row, 1768). (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail of the central motif on the façade of the chest illustrated in fig. 59. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

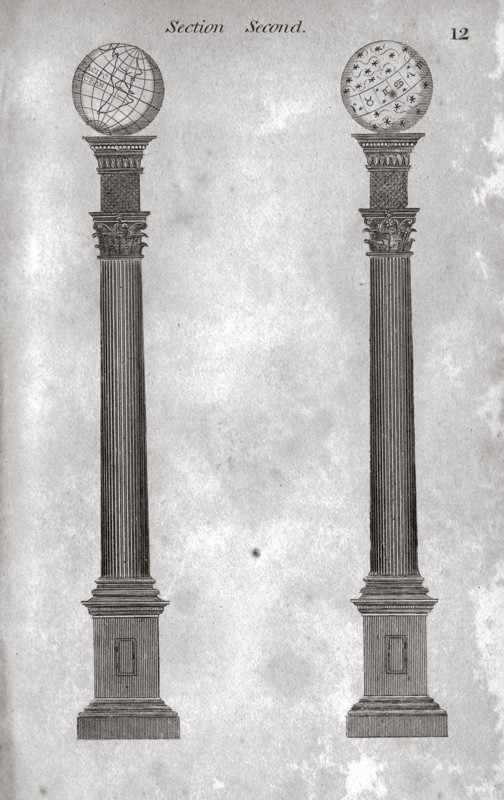

Detail of pillars topped with terrestrial and celestial globes (R. W. Jeremy L. Cross, G.L., The True Masonic Chart or Hieroglyphic Monitor, 5th ed. [New York, 1842], p. 12). (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) These pillars symbolized the Fellow Crafts Degree, Section Second.

Detail of the right bird on the façade of the chest illustrated in fig. 59. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The design of the birds on the chest is similar to that of the eagle in the lower right quadrant of the shield shown in fig. 65.

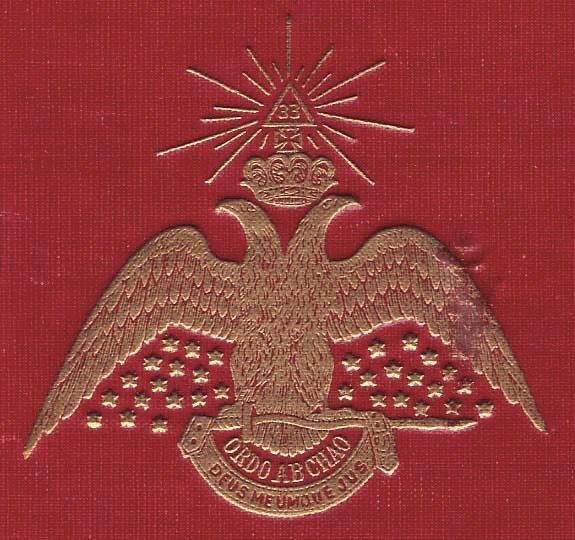

Detail of the cover of Albert Pike, Morals and Dogma of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry (1873).

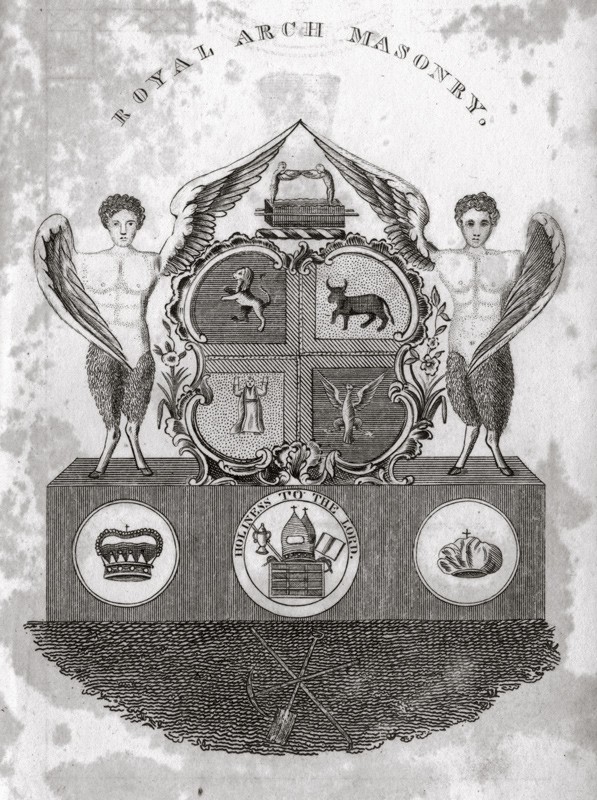

Detail of facing cherubim guarding the ark of the covenant (R. W. Jeremy L. Cross, G.L., The True Masonic Chart or Hieroglyphic Monitor, 5th ed. [New York, 1842], p. 42). (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail of the right building on the façade of the chest illustrated in fig. 59. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the right side of the chest illustrated in fig. 59. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

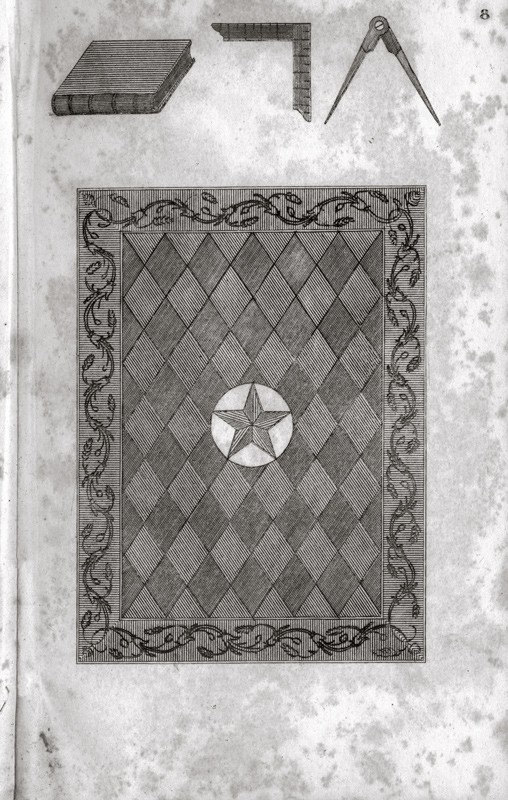

Detail of a Masonic floorcloth (R. W. Jeremy L. Cross, G.L., The True Masonic Chart or Hieroglyphic Monitor, 5th ed. [New York, 1842], p. 8). (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

John Luker, Masonic master’s chair, pillars, and candlestands, Vinton County, Ohio, 1870. (Courtesy, Scottish Rite Masonic Museum and Library, gift of the Estate of Charles V. Hagler; photo, David Bohl.) The shape of the large pillars is similar to that of the central motif on the chest illustrated in fig. 59.

Cupboard, Catawba, Lincoln, Cleveland, or Burke County, North Carolina, 1880–1920. Yellow pine. H. 52 1/2", W. 35 3/4", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The decorator typically used one ground color for the stiles and rails and another for the doors, top, and case sides. This allowed him to frame his ornamental designs.

Cupboard, Catawba, Lincoln, Cleveland, or Burke County, North Carolina, 1880–1920. Yellow pine. H. 53", W. 36", D. 16". (Private collection; photo, Wesley Stewart.) The brown may be a stain or wash rather than an opaque paint.

Dish dresser, Catawba, Lincoln, Cleveland, or Burke County, North Carolina, 1880–1920. Yellow pine. H. 76", W. 34", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The thick application of bright paint makes the more methodical decorator’s work particularly dramatic.

Composite detail showing the door decoration on (from left to right) a dish dresser (fig. 72) and two cupboards (figs. 70, 71). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth [left and middle] and Wesley Stewart [right].)

Cupboard, Catawba, Lincoln, Cleveland, or Burke County, North Carolina, 1880–1920. Yellow pine. H. 53", W. 36", D. 16 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Wesley Stewart.) The name “Zara Havner” is written in pencil on the inside surface of the left door. The only person with that name in North Carolina census records from the early twentieth century was an eight-year-old girl who lived in Icard Township in Burke County in 1900. She was the daughter of farmer Daniel A. Havner and his wife, Margaret.

Cupboard, Catawba, Lincoln, Cleveland, or Burke County, North Carolina, 1880–1920. Yellow pine. H. 52", W. 36", D. 16". (Private collection; photo, Wesley Stewart.) On this cupboard and the example illustrated in fig. 76, the decorator used lunettes to outline the diamonds and the designs beneath them. The methodical painter of the related cupboards and dish dresser used sawtooth lines in the same context. This cupboard is the only example with quatrefoil motifs, which may have been intended to represent flowers.

Cupboard, Catawba, Lincoln, Cleveland, or Burke County, North Carolina, 1880–1920. Yellow pine. H. 53", W. 36", D. 15 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Wesley Stewart.)

Composite detail showing the door decoration on cupboards illustrated in (from left to right) figs. 74, 75, and 76. (Photos, Wesley Stewart.)

Basket, Qualla Boundary, North Carolina, ca. 1950. River cane. H. 11", W. 9", D. 8 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Wesley Stewart.)

Basket, Qualla Boundary, North Carolina, ca. 1950. River cane. H. 16", W. 17 1/2", D. 8". (Private collection; photo, Wesley Stewart.)

Washstand, Iredell County, North Carolina, ca. 1850–1875. Yellow pine. H. 30 1/2", W. 31", D. 17". (Private collection; photo, Wesley Stewart.)

Detail of the compass rose on top of the washstand illustrated in fig. 80. (Photo, Wesley Stewart.)

During the last fifty years, scholars have published numerous books and articles on late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century furniture from the piedmont region of North Carolina. Most of their research has centered on hardwood case pieces and tables made by cabinetmakers including Mordecai Collins, Thomas Day, Peter Eddleman, James Gheen, William Little, Jesse Needham, and John Swisegood. By contrast, scholars have paid relatively little attention to paint-decorated furniture from North Carolina’s backcountry. Only a few groups of related objects are known, and until recently most makers have remained anonymous. Although the practice of decorating furniture was less prevalent in the piedmont region than in many other areas of the American backcountry, painted architectural fixtures and movables frequently brightened the interiors of early North Carolina homes. As this article will show, furniture makers in the piedmont region used yellow pine and poplar as the canvas on which to paint everything from traditional designs, such as fylfots and compass roses (figs. 1, 2), to abstract subjects almost impossible to interpret.[1]

Settling the Piedmont

The piedmont region of North Carolina is situated between the fall line in the east and the foothills of the mountains in the west (fig. 3). Between those geographic boundaries lie the gently rolling hills, plentiful rivers and streams, and rich soil that lured early settlers into the region. The search for cheap, fertile land began in earnest in the 1740s and 1750s. Thousands of settlers migrated from northeast North Carolina and southeast Virginia via the old Indian Trading Path, which came through Petersburg, Virginia, and Hillsborough, North Carolina. Others migrated from southeast North Carolina via the Cape Fear Road, which went through the fall line town of Cross Creek (Fayetteville). The large majority of settlers, however, made the long, arduous journey down what came to be known as the Great Wagon Road. Originating in Philadelphia, the Great Wagon Road followed a westward path through Lancaster, York, and Gettysburg in Pennsylvania, then turned south to traverse western Maryland and Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley before crossing into the North Carolina piedmont in present-day Rockingham County (fig. 4). Once they entered central North Carolina, the new inhabitants settled primarily along the Eno and Haw rivers in the eastern piedmont, the Deep and Yadkin/Pee Dee rivers in the central piedmont, and the Catawba River in the western piedmont.[2]

What started as a slow trickle of immigrants in the 1740s and 1750s turned into a deluge in the 1760s and early 1770s, and by the eve of the American Revolution white settlers had claimed most of the land in the piedmont. The state’s population mushroomed from about 35,000 in 1730 to more than 250,000 by the 1770s, with most of the new inhabitants settling in the piedmont. On November 30, 1767, the Connecticut Courant reported:

There is scarce any history . . . which affords an account of such a rapid and sudden increase of inhabitants in a back frontier country, as that of North Carolina. To justify the truth of this observation, we need only to inform our readers that twenty years ago there were not twenty taxable persons within the limits of the above-mentioned County of Orange; in which there now are four thousand taxable. The increase of inhabitants, and flourishing state of the other adjoining back counties, are no less surprising and astonishing.[3]

Early migrants to the piedmont region tended to settle in clusters with people who spoke the same language, observed similar religious practices and customs, and were of the same ethnic background. The largest and most widely dispersed group was Scotch-Irish, most of whom were Presbyterians from southeastern Pennsylvania. Also largely Presbyterian were the Highland Scots, who arrived as first-generation immigrants via the Cape Fear Road and settled in the southeastern section of the piedmont. Rounding out the English-speaking population were Anglicans and Quakers, who came from northeastern North Carolina, southeastern Virginia, southeastern Pennsylvania, as well as the northern colonies, and settled in the eastern and central piedmont. The German-speaking population was largely composed of migrants from Pennsylvania. Most settled in the central and western sections of the piedmont and were members of Lutheran, German Reformed, or Moravian churches. These settlement patterns created “a patchwork of religious and cultural enclaves” in the center of North Carolina (fig. 5).[4]

Most of the piedmont’s early inhabitants were nonslave-holding farmers who lived simply, often in one- or two-room log structures (fig. 6). Some also combined farming with the operation of cottage industries such as sawmills, gristmills, potteries, and blacksmith’s shops. Small towns like Hillsborough, Salem, Salisbury, Charlotte, and Lincolnton grew up around county courthouses and transportation routes, particularly intersections of roads and river crossings. Market towns and county seats like these provided residents with a place to buy goods that could not be produced locally, register deeds, and take care of other legal matters. As late as 1790, however, most towns in the piedmont region were no more than villages of a few hundred people.[5]

Transferring Style

A chest that reputedly descended in the Johannes Stirewalt (1732–1796) family of southern Rowan County shows how furniture and decorative painting styles arrived with early settlers of the piedmont region (fig. 7). Like so many of their Rowan County neighbors, the Stirewalts probably emigrated from southwestern Germany to Pennsylvania, then moved to North Carolina in search of inexpensive land. Not surprisingly, the chest resembles contemporary Pennsylvania German work in both construction and decoration. Made primarily of tulip poplar, the chest has a red lid and base and a board case with a mottled surface likely achieved by using crinkled papers to apply brown or ochre paint on a cream-colored ground. The lunetted panels on the front and sides have black mottling with four stylized tulips fingerpainted in a crosslike arrangement and white outlines for contrast (fig. 8). If the 1768 date between the front panels denotes the year of manufacture, then the Stirewalt chest is the earliest documented paint-decorated case piece from the piedmont region. By comparison, the earliest dated Pennsylvania chest with Germanic paint decoration was made in 1755 for an eleven-year-old Reading girl named Susanna Beyerin.[6]

The case, feet, and drawers of the Stirewalt chest are all joined with wedged dovetails; the drawer bottoms, case bottom, and chest moldings are attached with wooden pins; and the hardware includes a decorative crab lock (fig. 9), shaped keyhole surround, and long, tapered strap hinges with circular ends, one of which is attached to the back of the chest, the other to the interior backboard. Family tradition suggests that Johannes Stirewalt made the chest, but no documentary evidence corroborates this suggestion. There is little doubt, however, that the maker was part of the greater German migration that followed the Great Wagon Road from Pennsylvania into the North Carolina piedmont.[7]

Cultural and Stylistic Assimilation

Like many early Teutonic inhabitants of the piedmont region, the maker of the Stirewalt chest probably lived in a predominantly German community, attended a Lutheran or German Reformed church, and rarely socialized with his English-speaking neighbors. The latter were just as content with maintaining cultural separation, typically limiting interaction with their Germanic neighbors to trade or other financially profitable pursuits. By the first quarter of the nineteenth century, however, the children and grandchildren of the first wave of settlers had intermarried, raised their own children, and embraced English as their common language. If they were fortunate enough to become a part of the emerging elite, members of these later generations might live in frame (fig. 10) or brick houses rather than log structures. Many of them had been lured by the revivals of the Second Great Awakening from their parents’ faith to one of the new Methodist or Baptist churches sprouting up throughout the North Carolina piedmont. As historian Harry Watson noted, “an elderly grandparent or a handful of personal heirlooms was often all that kept alive the memory . . . [of a family’s ethnic origins].” At the turn of the nineteenth century, most inhabitants of the piedmont would have considered themselves North Carolinians.[8]

Most of the paint-decorated furniture surviving from the piedmont region was made after this period of assimilation. The synthesis of two different cultural aesthetics is reflected in the design and decoration of the chest illustrated in figure 11. It was probably made in southern Alamance County (created from Orange County in 1849), an area settled primarily by Germans and English Quakers. The ornament on the chest is reminiscent of that found on Pennsylvania German examples, but the case design is more British than German. The façade (figs. 12, 13) consists of three panels with ochre backgrounds over a light base, each containing stylized flowers with contrasting dots, or jeweling, and circular, compass-generated motifs. Many of the flowers and stems terminate in distinctive, lancet-shaped designs rendered in black or red. The initials “GR” on the center panel probably refer to the owner, but a plausible candidate has yet to be identified. Given the nineteenth-century date of the chest, the diamonds framing the panels may have been inspired by those on neoclassical inlaid furniture, which was popular in the piedmont region.[9]

With its tall bracket feet, board lid, and relatively simple moldings, the design of the GR chest has more in common with neat and plain British furniture than the more baroque case work associated with immigrant-generation artisans from Teutonic countries. The same can be said of many Pennsylvania decorated chests. As decorative arts historian Monroe Fabian and others have noted, the use of deeply stepped moldings and applied architectural ornament waned during the last quarter of the eighteenth century as Pennsylvania German artisans began producing simpler forms and incorporating British details like ogee feet. At the same time, the construction of this chest is more Germanic than British. All of the dovetails are wedged, and the feet, lid, and base moldings are attached with wooden pins.

Although its surface has been compromised by early attempts at cleaning, the chest illustrated in figure 14 is clearly by the same maker and decorator as the preceding example. The entire chest has a cream undercoat with dark ochre graining over that, black and cream flowers with a few red accents, dark blue and red base and top moldings, and blue molding above the drawers. Variations in the panel decoration on these two chests indicate that they were not laid out with patterns that transferred all of the design information at once. The templates used were either sectional or for individual elements. On the GR chest, the decorator used black bands with vertically stacked red lozenges to separate the center and end panels. On the chest illustrated in figure 14, he used black bands with interlocking cream-colored cymas—a common detail on late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century slipware from Randolph and Alamance Counties (fig. 15).

The lid of the chest illustrated in figure 14 bears the chalk inscription “Josiah C. Foster” (fig. 16), and the lid of its till is marked in pencil “Josiah C. Foster, this the 10 of Oct. 1849.” Although the maker has not been conclusively identified, decorative arts scholar Frank L. Horton considered Daniel Anthony (1812–1883) or his father, Henry (ca. 1777–1862), likely candidates. Both men lived in southwestern Alamance County and were part of the German Lutheran community that settled near Stinking Quarter Creek. A walnut chest (fig. 17) with drawer dovetails and feet matching those on the decorated chests (figs. 18, 19) descended from Daniel Anthony to his granddaughter Eleanor George of Gun Creek, along with a set of molding planes, two of which are marked “H. ANT[HON]Y.” Although family tradition maintained that Daniel was the chest’s maker, it is also possible that he inherited it from his father.[10]

The first Anthony documented in Orange County is Henry’s father, Jacob. The latter owned land near Stinking Quarter Creek in 1784 and was listed in the 1790 census. Henry appeared in the Orange County census from 1800 to 1840 and the Alamance County census from 1850 to 1860. The 1850 census referred to him as a “mechanic.” In 1814 Henry bought property north of Great Alamance Creek, which is slightly north of Stinking Quarter Creek. He died in 1862 and was buried in the cemetery of St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in Alamance County. Daniel was also listed in the 1850 Alamance County census as a “mechanic” and in censuses taken from 1860 to 1880 and, like his father, was buried at St. Paul’s.[11]

If Henry or Daniel Anthony made these three chests, then what do the inscriptions on the example illustrated in figure 14 signify? Josiah C. Foster could, of course, simply be the name of an owner. Another possibility is that he worked with one of the Anthonys. The 1860 Alamance County census listed a “J. C. Foster” who was thirty years old and identified as a farmer. He would have been nineteen when the 1849 date was inscribed on the chest, old enough to have been an apprentice in Henry and/or Daniel Anthony’s shop. Eleven years later, all three men lived in the Graham Post Office District just south of Graham, North Carolina. Additional evidence that J. C. Foster may have been a woodworker is the name and profession of his son Josiah. The 1910 census of Alamance County described Josiah C. Foster as a carpenter, suggesting that his father’s full name was the same as that inscribed on the chest, and that the younger Foster may have trained with his father. Although it is difficult to reconcile the chest’s design and decoration with a mid-nineteenth-century date, one cannot discount that possibility.[12]

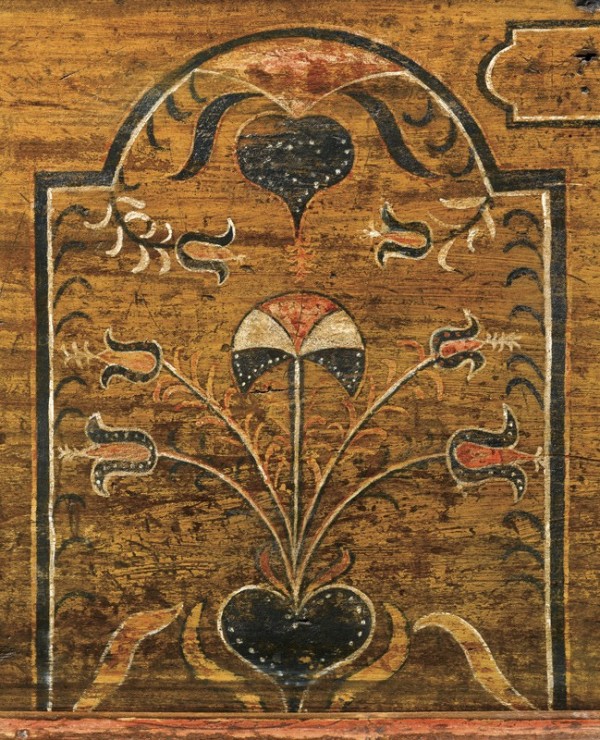

A chest recovered at Kimesville (fig. 20), a small Alamance County town southwest of Stinking Quarter Creek, appears to be related to the examples illustrated in figures 11 and 14. The façade of the former object has a small rectangular panel with astragal ends at the top and two large panels with astragal heads (fig. 21). Presumably, the upper panel displayed the initials of the owner and either a commemorative date or the year of manufacture, but now only a “B” and the numbers “1” and “3” are legible. Each of the large panels has black hearts with branching black, white, and orange flowers and leaves at the top and bottom. As on the related chests, the decorator depicted leaves and petals as simple cyma-shaped forms and used contrasting jeweling to highlight his designs. The most notable variations in the decoration of these objects are compositional. On the chests illustrated in figures 11 and 14, the panel designs radiate up and away from the center; on the example with the Kimesville history, stylized leaves and flowers also extend inward from the edges of the panels. Moreover, no layout marks are visible on the latter chest, and the stems, leaves, and protruding tulip stamens were painted freehand.[13]

Developing Local Preferences

Paint-decorated furniture made in the piedmont region during the first half of the nineteenth century often says more about the emergence of local design preferences than the persistence of old-world cultural traditions. The chest illustrated in figure 22 is related to several examples with histories of descent and recovery in Stanly and Cabarrus counties, an area where inhabitants of Scotch-Irish and German heritage lived side by side. With its salmon and blue background colors and white fylfots (fig. 23), hearts, and arched panels, this chest is the most ornate in the group. Although all of these motifs occur in the British decorative tradition, their arrangement on the chest—particularly the use of hearts between arched panels—is more closely aligned with Germanic work.

A chest that descended in the Cannon family of Cabarrus County has more subtle decoration (fig. 24). The front and sides have a mottled surface likely produced by dabbing blue-green paint on a white ground. Distribution of the blue-green coat suggests the decorator applied it with a cloth rather than a brush. He then used fingerpainting techniques to produce the fan-shaped design beneath the astragal panel on the façade and squiggles at the ends of the front and sides. As one would expect, the decorator laid out the panel with a compass and straightedge and applied all of the red paint—lid molding, base, panel outlines, letters, date—at the same time. Regrettably, the original owner of the chest, whose initials were probably “SMH,” has not been identified. Although now greatly diminished, the chest lid once had an additional larger astragal panel in the center and red and dark blue quarter fans at the corners of the top.[14]

A related chest (fig. 25) with a recovery history in Albemarle, a small town in Stanly County, has a dramatic, bichromatic paint scheme and a façade panel bearing the inscription “MARTHA MAULDEN WAS / BORN: AUG: 19: 1823.” No female with this birth date has been identified, but individuals with the same last name were listed in early census records for Stanly County. Assuming that Martha Maulden received this chest during her teens, its probable date of manufacture is 1835–1840. Although that date seems incongruent with the chest’s bold bracket feet and applied moldings, furniture styles remained behind the times in many areas of the piedmont.

As the designs and dates of the preceding examples suggest, more than one shop was responsible for the chests in the Stanly-Cabarrus County group. Moldings and bases on some examples are pinned, whereas the same components on other chests are nailed; the dovetails on some examples are wedged, whereas those on other chests are not. Connecting these objects is the consistent use of broad, bracket feet with cove-and-ovolo inner profiles. The most elaborate examples have an additional cove at the top and are taller than those that terminate in an ovolo (figs. 26, 27). The Maulden chest is the most structurally complex example in the group, although its nailed drawer frames and awkwardly coped vertical moldings suggest that it was made by a carpenter or house joiner rather than a cabinetmaker (fig. 28).

A much larger group of idiosyncratic, paint-decorated furniture originated in north-central Montgomery County and southwestern Randolph County (fig. 29). Several examples have recovery histories near the tiny communities of Ophir and Pisgah, which are only about ten miles apart. Most of the early settlers, who were primarily of British descent—English with a few Scotch-Irish and Highland Scots—occupied land near the Uwharrie and Little rivers and their feeder creeks. There were no towns of significant size in this relatively isolated area, but by the beginning of the nineteenth century small farms, gristmills, sawmills, and sporadic gold mines dotted the hilly landscape of the Uwharrie Forest.[15]

A few examples from this group may have been made during the late eighteenth century, but most date from the first half of the nineteenth century. The range of forms includes wall cupboards, corner cupboards, dish dressers, small hanging cupboards, and chests. Most are made of yellow pine and are either painted one color or decorated with contrasting colors, most often combinations of red, white, blue, and black. A few examples have been stripped, overpainted, or altered structurally, making their original decorative schemes unclear. Although variations occur within the group, the construction of these pieces typically includes the following features.

• Dovetailed cases (fig. 30). The uppermost dovetails on tall case pieces often protrude 1/8 inch to 1 inch above the top board. Some dovetails are wedged while others are not.

• Molded baseboards with integral feet. The boards are mitered at the front corners and nailed (fig. 31).

• Front baseboards that descend to a peak in the front center (fig. 29).

• Ogee moldings. These moldings are almost invariably applied with large nails and often used to outline the case and divide the façade (fig. 30).

• Doors with pinned mortise-and-tenon frames and raised panels.

• Heavy beading around openings and on raised panels and the edges of drawers and doors (fig. 30).

• Dovetailed drawer frames with bottoms that are nailed into the sides, front, and back. A few pieces have nailed drawer frames.

• Cornices composed of wide molded boards (see fig. 36) or narrower single or stacked moldings (fig. 32). The most common molding is a filleted ogee. The cornices of large case pieces often have decorative fascias with dentils, lunettes, or sawtooth repeats at the bottom.

• Varied door hardware, although strap-and-pintle hinges are common (figs. 30, 31).

• Wrought nails often with original cut nails.

Only two objects in the Montgomery-Randolph County group are decorated with painted motifs. The chest and dish dresser illustrated in figures 33 and 44 have white fylfots and compass roses set against circular, dark blue and black grounds respectively. The chest also has a similarly painted astragal panel bearing the initials “SP,” and the front edges of its case, moldings, and feet are painted blue. On most of the objects in this group, the front edges of the case are covered with applied ogee moldings. To attach the lid to the backboard of the chest, the maker used thin strap hinges with pintle joints (fig. 34). Both hinge sections are secured with clinched wrought nails.

The paint on the cupboard illustrated in figure 29 is more typical of the group. The decorator used contrasting colors to accentuate the panel bevels, applied moldings, drawer fronts, and base. The most striking application of polychrome paint, however, is on the cornice (fig. 32), which is composed of three separate sections: the upper ogee is red with a green fillet; the lower ogee is green with a white fillet; and the lunettes of the fascia below repeat a red, creamy white, red, and green sequence.

Recent paint analysis revealed that the red paint, which now resembles a thin wash, was originally a much thicker layer composed of red ochre and red lead pigments in linseed oil. The creamy white paint created from white lead and linseed oil was originally much brighter, and what now appears to be a black accent color was originally green. For the green, the decorator mixed Prussian blue, yellow ochre, and white lead pigments in linseed oil. Although it is impossible to determine when exposure to light, dirt, and other factors altered the appearance of the cupboard, its paint scheme would originally have been more dramatic than it appears today. Given the fact that these objects were probably made by carpenters, their paint colors, moldings, and other decorative details may have been chosen to resonate with those of the interiors they occupied.[16]

The dish dresser illustrated in figure 35 has a paint scheme similar to that of the cupboard (fig. 29) but with blue rather than green accents. Its cornice is made of a wide board with a filleted ogee at the top and a smaller ogee below. The fascia has a lunetted fret with a drilled plaque in the center of the façade and a sawtooth lower edge. As was the case with the cupboard, the dresser’s cornice has a complex polychrome decoration: the filleted ogees are blue and red with blue fillets while the fret and sawtooth border are white with alternating red, blue, and white pierced lunettes (fig. 36). Also adding to the visual impact of the dresser are the shaped stiles, rails, and board appliqué—cut to simulate superimposed columns—of the upper section. The inner edges of the stiles and rails are highlighted with blue paint, and the outer edges of the board appliqué are tipped with white.[17]

The craftsmen responsible for the Montgomery-Randolph County group often used similar decorative details on different forms. A small hanging cupboard has scalloped stiles and rails (fig. 37) that resemble those on the dish dresser illustrated in figure 38. Because the latter object was altered at a later date, it is impossible to determine if its scalloped edges were highlighted with blue paint like those on the cupboard. Another hanging cupboard is basically a smaller version of the upper section of standard wall cupboards from this group (fig. 39). Its red surface is in good condition, but the blue areas have been overpainted and the cross on the door is probably a later embellishment. The hinges on this hanging cupboard are unusually ornate, and their tripartite ends may represent stylized flowers (fig. 40).[18]

In addition to making paint-decorated objects, the artisans responsible for the Montgomery-Randolph County group also produced walnut furniture. The chest of drawers illustrated in figure 41 shows how the maker used inlays and appliqués to replicate painted details. He substituted lightwood cock-beading for painted edging and a lunetted maple fascia for a polychrome one (fig. 42). The horizontal crescents on each of the top drawers do not have precise cognates in paint, although their basic shape is echoed in the scalloped rails of the hanging cupboard and dish dresser illustrated in figures 37 and 38. Unlike urban artisans who occasionally used paint to simulate more costly inlay, the rural maker of this chest did the opposite.

No two objects in this group are exactly alike, which suggests that they are the products of a large shop tradition with multiple makers. Variations in the molding sequences, frets, and decorative fascias of cornices could have resulted from efforts to make those details match corresponding features in their intended architectural setting, but that does not explain the use of at least six different foot patterns. Local patrons apparently wanted objects that were different from those of their neighbors, and the makers associated with this group used a broad range of foot designs, cornice treatments, and paint schemes to satisfy a demand for variety.

The penciled inscription “S. D. Hardister” on the backs of both upper doors on the cupboard illustrated in figure 29 initiated research that suggests Jacob Sanders (ca. 1765–ca. 1817), his son Jacob L. Sanders (1799–ca. 1865), and possibly his grandson Ira Sanders (1821–ca. 1905) made most of the objects in the Montgomery-Randolph County group. A man named Green Hardister appears in the 1830 census of Montgomery County and as the owner of property “on the southeast side of Uhari [Uwharrie] River on the Dark fork of Barnns Creek” six years later. In the 1850 census, his wife Margaret and son Ezekiel were listed as being fifty-five and twenty-five years of age respectively. Ten years later, the census takers listed “Peggy” Hardister as a widow still living with Ezekiel. Green Hardister’s estate records contain no evidence that he was a carpenter, but they do indicate that he was allied with the Sanders family.[19]

Peggy Hardister was the daughter of Jacob and Mary Sanders. The 1790 Montgomery County census listed Jacob as the head of a household containing seven other people, most likely his wife and six children. His name appears in numerous land warrants and surveys starting in 1794, and, like his son-in-law Green Hardister, Sanders owned property on Barnes Creek. Jacob’s estate records were probably destroyed in one of several Montgomery County courthouse fires, but family tradition supports the theory that Jacob was a carpenter. According to a 1965 letter written by his great-granddaughter Phebe Hoge, Sanders “built household furniture with the use of hand tools and sold them. I don’t know how many children they [Jacob and Mary] had, but he gave each . . . a homemade chest—made soon after they were born in which to keep their clothing.” The small chest illustrated in figure 43 may represent the type Jacob made for his children.[20]

At least one of Jacob’s sons was also a woodworker. The 1850 Montgomery County census listed Jacob L. Sanders as a fifty-one-year-old carpenter, and it is likely that he learned his trade from his father. The younger Jacob and his family subsequently moved into the New Hope Township in southern Randolph County, where he was listed as a carpenter again in the 1860 census. Although there is no documentation that any of his brothers were woodworkers, the 1860 Randolph County census listed his thirty-nine-year-old nephew Ira as a carpenter. It is highly likely that Jacob Sanders, his son Jacob L., and possibly his grandson Ira made the majority of the objects in the Montgomery-Randolph County group.

Inscriptions on two objects support attribution of the group to the Sanders family of woodworkers. The name “S. D. Hardister” on the cupboard illustrated in figure 29 may refer to Sara Della Hardister (b. 1864), the daughter of Ezekiel Hardister and Louisa Sanders. (This Ezekiel appears to be the son of Wiley and Candis Hardister, not the aforementioned son of Green and Peggy Hardister.) Louisa’s father, Sampson, was one of the elder Jacob Sanders’s sons and a brother to Jacob L. Other than Sara Della, no other person with the initials S. D. and last name Hardister has been found in Montgomery and Randolph County records of the period. If she is the S. D. Hardister whose name appears on the cupboard, then this object may have descended from Jacob Sanders, to his son Sampson, to Sampson’s daughter Louisa and to her daughter Sara Della.[21]

The dish dresser illustrated in figure 35 has the name “George M. Allen” inscribed in pencil on a lower shelf support. A George Allen owned property on Barnes Creek near the Hardister and Sanders families. His 1848 estate inventory listed several lots of plank; two log chains; heavy woodworking tools including crosscut saws, adzes, and axes; “1 set saw mill Irons” valued at $20.00; and “1 [set of] . . . smith’s tools” valued at $26.10. These items and the high values assigned to them suggest that George Allen was a blacksmith who may also have operated a sawmill. It is possible that he provided the lumber and many of the hinges and forged nails used on the furniture presumably produced by members of the Sanders family. If that theory is correct, the dish dresser could have been commissioned by Allen or taken in payment for lumber and blacksmith work.[22]

Five dish dressers in the Montgomery-Randolph County group appear to have been made by an artisan familiar with but outside the Sanders shop tradition. The example illustrated in figure 44 has fylfots and compass roses like those on the chest bearing the initials “SP” (fig. 33), but its case is nailed rather than dovetailed; its feet are dovetailed rather than nailed; and its front baseboard is only slightly peaked. The dish dressers in this aberrant group also differ from their mainstream counterparts (see figs. 35, 38) in having flat door panels and tops composed of a single board with no applied cornice. Although the maker of these five related dressers was influenced by furniture from the Sanders shop tradition, his use of entirely different construction techniques suggests that he probably did not train with a member of that family.

Nationalism, Neoclassicism, and Fancy

By the early nineteenth century, national and international styles began influencing the decorative arts of the piedmont region. On the chest illustrated in figure 45, a central cream motif resembling a cut-paper valentine (fig. 46) and seven cream-and-black compass roses are combined with cream neoclassical drapery swags with black tassels. Although the latter are somewhat naively painted, they reflect the backcountry decorator’s awareness of this popular neoclassical pattern.

Three chests from the Chatham-Randolph County area have stylized foliate borders resembling those commonly engraved on neoclassical silver and façades decorated with eagle and starburst motifs set in jeweled circles. Eagle motifs became increasingly popular after that bird was depicted on the Great Seal of the United States in 1782. The chest illustrated in figure 47 descended in the E. W. Reitzel family of Chatham County. With the exception of its circular reserves, which were laid out with a compass, all of the decoration was done freehand. The focal point of the decorator’s design is an eagle with folded wings and a shield on its breast (fig. 48). In most versions of this popular design, the eagle clutches a leafy branch in one talon and a cluster of arrows in the other. Often the eagle’s head is encircled with stars, and in some versions the bird holds a banner—occasionally bearing the inscription “E PLURIBUS UNUM”—in its beak. The decorator of this chest and the similar example illustrated in figure 52 deviated from those designs by placing his eagle on a stylized orb and adding yellow flourishes to the banner in its beak. Those flourishes may represent the leafy branches in more conventional adaptations. Possible inspirations for this artisan’s work can be found on period coins and touchmarks on pewter and silver. A 1787 doubloon by New York goldsmith and jeweler Ephraim Brasher depicts a dropped-wing eagle framed by a circular wreath (fig. 49). On the opposite side of that coin is a rising sun with a circular beaded border that resembles the jeweled reserves on the chest. A similar dropped-wing eagle also appears on pewter plates by Jehiel Johnson (fig. 50), who worked in Fayetteville, North Carolina, between 1817 and 1819. Objects from Johnson’s shop may well have been in Chatham and Randolph counties during the period when these chests were made.[23]

The sides of the chest illustrated in figure 47 feature a jeweled square with radiating brushstrokes that resemble fireworks (fig. 51). Pyrotechnical displays were extremely popular in the South, as indicated by an advertisement in the July 2, 1807, issue of the South Carolina Gazette and Daily Advertiser: “The 4th July, Being the Grand . . . Day of the INDEPENDENCE OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, will be displayed . . . the most Superb and Variegated collection of FIRE WORKS, that ever yet has been exhibited in this city.” Alternatively, the radiating design on the sides of the chest could have mimicked kaleidoscopic patterns, which were prevalent in fancy decorative arts of the early nineteenth century.[24]

According to Reitzel family tradition, the maker of the chest illustrated in figure 47 was J. R. Edwards. The 1850 census of Chatham County identified a James Edwards as a forty-year-old carpenter and resident of the “western region.” Thirty years later, the census recorded that Edwards lived in Matthews Township in the southwestern part of Chatham County and had a seventeen-year-old son named Jas. R. The recurrence of the same neighbors in both censuses indicates that the elder Edwards remained in the same location from 1850 to 1880. Members of the Reitzel family appear in Chatham County records by 1900. The census for that year listed farmer Henry Reitzel and his sixteen-year-old son Eugene W. The latter was probably the E. W. Reitzel from whom the chest descended.[25]

Determining who made the chest is more problematic. There is no evidence that the younger Jas. R. Edwards was a woodworker, and he was born much too late to have made the chest. If that object’s 1801 date is commemorative, then his father, James, can be considered a possible maker. The elder Edwards would probably have completed his carpentry training about 1830. Although that date seems late for the chest, another example by the same decorator is dated 1824.[26]

Except for its color scheme, the decoration on the chest illustrated in figure 52 is essentially the same as that on the Reitzel family example. The former object has a salmon primer coat and ground, and its primary motifs, borders, and jeweling are executed in ochre, black, and white paints. The design and construction of the bracket feet differ significantly from those of the Reitzel chest, indicating that these two chests are not by the same maker. On the chest illustrated in figure 52 the backs of the rear feet are cut from a single board that is arched in the middle rather than being dovetailed and nailed individually as they are on the Reitzel chest (fig. 51).[27]

Neoclassical urns (fig. 53), plaited baskets (see fig. 56), and delicate foliate designs distinguish a group of five chests likely made in northeastern Chatham County. Similar motifs occur on needlework, watercolor, and velvet pictures produced in female academies during the first half of the nineteenth century. All of the chests have a dark blue ground and decoration in varying shades of yellow, green, and either pink or red, but structural variations indicate that they are by at least three different makers.[28]

A chest bearing the initials “LB” (fig. 53) is simply but neatly constructed. The case is dovetailed, the feet are mitered at the front corners and nailed together, and the base and lid moldings are secured with nails. The rear feet extend beyond the back and are nailed to angular supports attached to the bottom of the case. Each support has a beveled upper edge to make it less visible when viewed from the side (fig. 55).

Although made by a different hand, the chest illustrated in figure 56 was painted by the same decorator as the LB chest. Both pieces have foliate borders on the edges of the façade that may have been stenciled rather than painted freehand. On the LB chest the design flows up, but on the other example (fig. 56) the direction is reversed. The urn on the former (fig. 54) and basket on the latter appear to have been partially laid out with a compass and straightedge, then finished freehand. The leaves, flowers, and decorative flourishes associated with the urn and the basket were also hand painted.

The attribution of this group to northeastern Chatham County is based on recovery histories and oral tradition. A chest (not illustrated) reputedly made for William A. Marcum (b. 1819) and a similar example reputedly made for his wife Nancy (b. 1824) bear the initials “WM” and “NM” respectively. The former chest is decorated with a basket of flowers, whereas the latter has an urn with flowers. The chests were probably made around the date of their wedding in 1842. The Marcums and their children were listed in Chatham County census records from 1850 to 1860, when they were residents of the Williams Store Post Office District in the northeastern part of the county.

Although probably made during the mid-nineteenth century, the chests in this Chatham County group have urns and other decorative details with classical origins. The retention of such designs was unusual for the period, because the dominant aesthetic of the second quarter of the nineteenth century was anticlassical. As decorative arts scholar Sumpter Priddy has shown, the widespread shift to nonrepresentational art in Western cultures began with the invention of the kaleidoscope in 1815. Enthralled by that novelty’s ability to create a seemingly endless variety of multicolored fractal designs, artisans and their patrons began experimenting with color and pattern. As the rational gave way to the romantic, paint decoration on furniture became increasingly whimsical and abstract. The purpose of highly stylized designs, kaleidoscopic patterns, and radical paint schemes was to delight the observer’s fancy.[29]

The decoration on a chest with a recovery history in Rutherford County shows how one piedmont artisan responded to these philosophical and stylistic changes (fig. 57). With its red ground and black arcs and dots, the decoration on the façade of the chest may be an abstract representation of mahogany. Unlike most eighteenth-century painters, who endeavored to mimic different species of wood as closely as possible, their nineteenth-century counterparts favored palettes and patterns that were not strictly governed by nature. The sides of the chest are decorated with corner fans and dots, and the frame is painted in a mottled pattern. Given the fact that complexity and variety were important aspects of fancy, this artisan’s use of different designs was undoubtedly intentional.

A chest with a similar frame (fig. 58) has a recovery history in Mecklenburg County, which is just east of Rutherford County. Loosely painted onto its reddish brown base coat is a stylized tree, circular motifs with jeweled perimeters (possibly representing fruit or nuts), abstract quarter-fans, and lozenge-shaped designs. For contrast and additional variety, the decorator painted the frame black and added cross-hatching. As Priddy has noted, the fancy aesthetic included the imaginary: “From caricatured . . . painting, it was a simple step for the ingenious [decorator] . . . to leave behind all hints of wood grain and move toward highly imaginative and completely original designs.”[30]

Fancy painted furniture was intended to catch the eye and awaken the mind. The stylized “pointillist” swags, diapering, and graphic images on a singular chest with a recovery history near Lake Mirl in northeastern Wake County would have undoubtedly delighted the fancy of both its maker and owner (fig. 59). As is the case with many fancy objects, the decoration on this chest probably had layers of meaning. Some of the designs may be Masonic. The halo of dots outlining both the central column and birds is reminiscent of the halo encircling the three lights of the lodge—the sun, the moon, and the worshipful master (fig. 60). The perpendicular design topped with an orb in the center of the chest (fig. 61) could refer to one of those lights or one of the three pillars, which designated both the legendary grand masters—King Solomon, Hiram of Tyre, and Hiram Abiff—and the officers of a lodge. In nineteenth-century Masonic decorative arts, the pillars often assumed the form of simple columns surmounted by globes (figs. 62, 69). Similarly, the birds on the chest (fig. 63) may have been adapted from the double-headed eagle associated with Scottish Rite Freemasonry, which was first established in America in 1801 (fig. 64), or they could represent the two facing angels that guard the ark of the covenant, arguably the holiest object in King Solomon’s Temple (fig. 65). The gable-fronted buildings beneath the birds (fig. 66) may allude to Freemasonry’s roots in craft, and specifically to the importance of architecture within the fraternity: the parts of a building being “united . . . [to] form a beautiful, perfect, and complete whole.” The intricate dotted pattern forming diamonds and triangles on the side of the chest (fig. 67) might represent the mosaic pavement of the lodge, which was “emblematical of human life, chequered with good and evil” (fig. 68). Lending credence to these interpretations is the chest’s dark blue ground. That color is common on Masonic furniture (fig. 69) and is traditionally associated with the regalia of the lodge.[31]

The motifs on this chest can be read in other ways as well. Because the painter’s depiction of the birds is highly stylized, they could represent doves, phoenixes, neoclassical eagles, or angels. Viewed in tandem, the birds could also allude to the union of two people in marriage. Perhaps the entire frontal tableau might be visionary and, as with much visionary art, should be viewed subjectively. Might the design be a representation of mere mortals living in earthbound abodes but protected by hovering spirits that owe allegiance to an even greater, all-seeing power—one with a big red eye? Although one is tempted to ascribe “mystical” attributes to some of these motifs, the decoration on this chest may simply reflect the idiosyncrasies and whims of its painter.

Postindustrial Craft

Factory-made furniture became increasingly available in piedmont North Carolina during the last half of the nineteenth century, but in many isolated areas cabinetmakers, house carpenters, and other woodworkers continued to make objects by hand. Where Catawba, Lincoln, Cleveland, and Burke counties meet in the western piedmont, an artisan with limited furniture-making skills produced at least ten paint-decorated cupboards (figs. 70, 71, 74, 75, 76) and one dish dresser (fig. 72). The construction of the cupboards is remarkably consistent.

• All are approximately 53 inches high, 36 inches wide, and 16 inches deep.

• The feet are cut from the front stiles and board sides.

• The rails and stiles are lap-joined and nailed together.

• The doors are single planks and often have two battens on the back to keep them from cupping.

• The two-board tops have a molded edge.

• The edges of the outer backboards are flush with the top and sides and are nailed in place.

• Pulls are spool-shaped.

• Doors are attached with butt hinges and generally held shut with a turnbuckle at the top and bottom; a few have a third central turnbuckle.

• Interiors contain two nailed-in shelves.

• Components are attached with both cut nails and round nails.[32]

All of the furniture in this group has bright polychrome decoration. Paint colors include red, green, and yellow, and, to a lesser extent, brown, blue, and white. The door decoration on these objects probably represents the work of two artisans, possibly members of the same family. One decorator applied his paint precisely, following lines scribed with a compass and straightedge, whereas the other was less regimented and rarely used layout tools.

The cupboards and dish dresser illustrated in figures 70, 71, and 72 are by the more methodical decorator. His work is geometric and often features straight lines that intersect to create triangles, curved lines that form half and quarter circles, sawtooth lines, and motifs resembling crosses and stylized trees (fig. 73). The trunks of the trees and the lines forming the crosses were laid out with a straightedge, but the sawtooth borders and tree “boughs” were painted freehand. Although the overall decoration on each cupboard is unique, the basic design elements are the same and, regardless of how they are combined, the overall effect is balanced. The top half of each door is usually a mirror image of the bottom half.

The cupboards illustrated in figures 74, 75, and 76 represent the work of a second painter, whose stylistic vocabulary included diamond chains, quatrefoils, and lunettes (fig. 77). Although he also used stylized tree and cross motifs like the orderly painter of the preceding cupboards and dish dresser, the second decorator’s doors do not have mirror-image designs, and his brushwork is broader and much less controlled. Apparently, these decorators worked concurrently, since all of the furniture in this Catawba Valley group appears to be by the same maker.

The motifs on this furniture are difficult to interpret. The triangles could represent the Trinity, the trees could signify the Tree of Life, and the crosses could allude to Christ’s sacrifice. Alternatively, some of the geometric designs could have been inspired by Cherokee decorative patterns as represented in the baskets illustrated in figures 78 and 79. The latter scenario seems possible since members of that Indian nation lived slightly west of the area where the cupboards were made. One local tradition maintains that the pieces were sold at a hardware store near the town of Casar in Cleveland County, whereas another tradition suggests that a minister made them. The name “four corners group” has recently been applied to these objects because they were made in a region where the boundaries of four counties meet.[33]

One final object suggests the willingness of piedmont North Carolina woodworkers to embrace new forms while adhering to traditional styles and decorative motifs. Although made in the last half of the nineteenth century, the red, green, and yellow Iredell County washstand illustrated in figure 80 combines traditional decorative motifs—a compass rose on top (fig. 81) and a slightly smaller circle on the bottom shelf—with neoclassical tapered legs and a Gothic revival skirt. The creative juxtaposition of the new and the old attests to the strength of piedmont North Carolina’s paint-decorated furniture tradition. One has to wonder what other colorful treasures of its ilk are yet to be discovered.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article, the author thanks Gavin Ashworth, Charlotte and L. C. Beckerdite, Eric N. Blevins, Mark and Lisa Chandler, Tara Chicirda, Claire and Newton Crouch Jr., Bill and Annette Ivey, Leland Little, Steve Lott, Shane and Melanie Manuel, Patricia Marshall, Craig McDougal, Ralph Newsome, Daniel Ray Owen, Jane and Rob Pearce, Scott Philyaw, Sumpter Priddy, Danny Richard, Gary B. Sanders, Gretta Saunders, Tom and Sara Sears, Scott and Wendy Smith, David Springs, Wes Stewart, and Jon Zachman.

For more on cabinetmakers in the piedmont region, see Rodney D. Barfield and Patricia M. Marshall, Thomas Day: African American Furniture Maker (Raleigh: North Carolina Office of Archives and History, 2005); Frank L. Horton and Carolyn Weekley, The Swisegood School of Cabinetmaking (High Point, N.C.: Hall Printing, 1973); John Bivins, “A Piedmont North Carolina Cabinetmaker: The Development of Regional Style,” Antiques 102, no. 5 (May 1973): 968–73; Carolyn J. Weekley, “James Gheen, Piedmont North Carolina Cabinetmaker,” Antiques 102 , no. 5 (May 1973): 940–44; Frank L. Horton, “William Little, Cabinetmaker of North Carolina,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 4, no. 2 (November 1978): 1–25; and Luke Beckerdite, “City Meets the Country: The Work of Peter Eddleman, Cabinetmaker,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 6, no. 2 (May 1980): 59–73. Approximately sixteen examples of paint-decorated furniture from the piedmont region have been illustrated. For examples, see North Carolina Furniture, 1700–1900, edited by Robert E. Winters Jr. (Raleigh: North Carolina Museum of History, 1977), pp. 19, 35, 38; Monroe H. Fabian, The Pennsylvania-German Decorated Chest (New York: Main Street Press, 1978), pp. 106–7; Dean A. Fales Jr. and Robert Bishop, American Painted Furniture, 1660–1880 (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1979), pp. 77, 250; Carolina Folk: The Cradle of a Southern Tradition, edited by George Terry and Lynn Robertson Myers (Columbia: University of South Carolina, 1985), pp. ii, 76, 78; Sumpter Priddy III and Luke Beckerdite, “Furniture of the Carolina Piedmont: Tradition and Taste,” in Terry and Myers, eds., Carolina Folk, pp. 56, 57; J. Roderick Moore, “Decorated Furniture,” in Southern Folk Art, edited by Cynthia Elyce Rubin (Birmingham, Ala.: Oxmoor House, 1985), pp. 144, 147, 148, 150, 157, 162; John Bivins and Forsyth Alexander, The Regional Arts of the Early South: A Sampling from the Collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 1991), p. 119; Ronald L. Hurst and Jonathan Prown, Southern Furniture: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1997), pp. 496–98, 507–10; and Sumpter Priddy, American Fancy: Exuberance in the Arts, 1790–1840 (Milwaukee, Wis.: Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 102–3. Orange County inventories from 1800 to 1808 were used as an index to help determine the prevalence of painted or decorated furniture in piedmont households (Orange County Records, Volume XVI, Inventories and Accounts of Sales, 1800–1808, edited by William Doub Bennett [Raleigh, N.C.: Oak Grove Press, 1995]). The inventories listed very few painted objects and no furniture described as “paint-decorated.” Typical entries are “1 painted chest” (p. 41), “2 Red painted tables” (p. 42), “1 Blew Cupboard / 1 Red Cupboard” (p. 50), “4 red chairs / 1 red table” (p. 73), “1 red chest / 1 blk. Chest / 1 white chest” (p. 78), “1 painted bedstead” (p. 81), and “2 painted presses for papers” (p. 89). Numerous paint pigments were available in the piedmont region. The Salem (North Carolina) Community Store Journal, 1814–1815 lists “white lead / Prussian blue” (p. 5), “red lead / Sp. Brown” (p. 7), “Brown ocre / Ocre” (pp. 30–31), and “verdigreece” (p. 127) (Old Salem Museums & Gardens, Winston-Salem, N.C.). In the December 3, 1804, issue of the Raleigh (North Carolina) Minerva, Joseph and William Peace advertised “White lead, Spanish Brown, yellow Ochre, Prussian Blue, Patent Yellow, Lampblack, and verdigrise.”

Catherine W. Bisher and Michael T. Southern, A Guide to the Historic Architecture of Piedmont North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), pp. 3–11. Elizabeth A. Fenn and Peter H. Wood, “The Great Wagon Road,” in The Way We Lived in North Carolina, edited by Joe A. Mobley (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), pp. 79–82. Parke Rouse Jr., The Great Wagon Road from Philadelphia to the South (Richmond, Va.: Dietz Press, 2004).

Bisher and Southern, Historic Architecture of Piedmont North Carolina, pp. 9, 13. Connecticut Courant, November 30, 1767.

For more on the British settlement of the piedmont region, see James G. Leyburn, The Scotch-Irish: A Social History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1962); H. Tyler Blethen and Curtis W. Wood Jr., From Ulster to Carolina: The Migration of the Scotch-Irish to Southwestern North Carolina (Raleigh: North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1998); Duane Meyer, The Highland Scots of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1961); Francis Charles Anscombe, I Have Called You Friends: The Story of Quakerism in North Carolina (Boston: Christopher Publishing House, 1959); and Seth B. Hinshaw, The Carolina Quaker Experience, 1665–1985 (Davidson, N.C.: Briarpatch Press, 1984). For more on the German settlement in the piedmont, see G. D. Bernheim, History of the German Settlements and of the Lutheran Church in North and South Carolina (1872; reprint, Baltimore: Regional Publishing Company, 1975); History of the Lutheran Church in North Carolina, edited by Jacob L. Morgan, Bachman S. Brown Jr., and John Hall (N.p.: United Evangelical Lutheran Synod of North Carolina, n.d.); Daniel B. Thorp, The Moravian Community in Colonial North Carolina: Pluralism on the Southern Frontier (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1989); C. Daniel Crews, Villages of the Lord: The Moravians Come to Carolina (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Moravian Archives, 1995); C. Daniel Crews, My Name Shall Be There: The Founding of Salem (with Friedberg, Friedland) (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Moravian Archives, 1995); The Autobiography and Chronological Life of Reverend Paul Henkel (1754–1825), edited by Melvin Miller et al. (Harrisonburg, Va.: Campbell Copy Center, 2002); and S. Scott Rohrer, Hope’s Promise: Religion and Acculturation in the Southern Backcountry (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2005). Fenn and Wood, “Great Wagon Road,” in Mobley, ed., Way We Lived, p. 78.

For more on life in the piedmont region, see Bisher and Southern, Historic Architecture of Piedmont North Carolina, pp. 15–18; and Watson, “An Independent People,” in Mobley, ed., Way We Lived, pp. 122–30.

The Beyerin chest is in a private collection. I thank Luke Beckerdite for this reference.

All information pertaining to the paint decoration, construction, and history of the Stirewalt chest was obtained from the curatorial report provided by the North Carolina Museum of History, Raleigh (acc. 2203.126.1), and from my inspection of the object. A description of the decoration, construction, and hardware on Pennsylvania German chests can be found in Fabian, Pennsylvania-German Decorated Chest, pp. 38–67; chests with graining and fingerpainting similar to those on the Stirewalt chest are illustrated in figs. 127, 202, 234; hardware similar to that on the Stirewalt chest is illustrated on pp. 93, 95. For more on the Stirewalt family, including the undocumented association of both John Stirewalt Sr. and his son John Stirewalt Jr. with the building and carpentry trade, see Davyd Foard Hood, The Architecture of Rowan County: A Catalogue and History of Surviving 18th, 19th, and Early 20th Century Structures (Salisbury, N.C.: Historic Salisbury Foundation, 2000), pp. 93, 251.

James S. Brawley, The Rowan Story, 1753–1953: A Narrative History of Rowan County, North Carolina (Salisbury, N.C.: Rowan Printing Company, 1953), pp. 29, 52. Watson, “Independent People,” in Mobley, ed., Way We Lived, pp. 107, 116. Bisher and Southern, Historic Architecture of Piedmont North Carolina, pp. 20, 27–29.

For Pennsylvania chests with related decoration, see Fabian, Pennsylvania-German Chest, pp. 130–32, 191. English chests of drawers with tall, narrow bracket feet are illustrated in David Knell, English Country Furniture: The National and Regional Vernacular, 1500–1900 (New York: Cross River Press, 1992), pp. 85–86.

For Horton’s attribution, see Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (hereafter cited as MESDA), Winston-Salem, N.C., object database S-1248. The birth and death dates of Henry and Daniel Anthony were taken from their tombstones in St. Paul’s Lutheran Cemetery on Bellemont-Alamance Road in Alamance County. Ruby Clapp Pentecost also makes claim to the cabinetmaking history of the entire Anthony clan, stating, “Furniture in the home [of ‘Little Daniel Anthony,’ son of William Anthony, who was a brother of Daniel Anthony] had been made by Jacob, Henry, Daniel, a brother of William, or Little Daniel himself” (as quoted in Alamance County: The Legacy of Its People and Places, edited by Elinor Samons Euliss [Greensboro, N.C.: Legacy Publications, 1984], pp. 40–41). All information pertaining to the construction and history of the Anthony chest was obtained from the curatorial report provided by the North Carolina Museum of History, Raleigh (acc. 1990.182.4), and from my inspection of the object. The molding above the drawers on the walnut chest illustrated in fig. 17 differs from that on the two painted chests. The shape of the back feet on the walnut chest is also different, as are the glue blocks on all three examples.

All census information used in this article was obtained from census page images available through the subscription database www.Ancestry.com. Orange County Records, Vol. III, Deed Book 3, Abstracts, edited by William D. Bennett (Raleigh, N.C.: privately published, 1990), p. 27. Will of Jacob Anthony, July 31, 1828, Orange County Wills, North Carolina Archives, Raleigh. In this document, Jacob refers to Henry as his son. Orange County Records, Volume XVIII, Deed Book 14, edited by William Doub Bennett (Raleigh, N.C.: privately published, 1996), p. 94. Henry’s wife Mary (Garrett) died in 1864 and was buried in the same cemetery as her husband. Daniel’s wife Barbara (Albright) was also buried at St. Paul’s.

A dated chest made by Jonathan Long (MESDA object database S-13565) in northern Davidson County, North Carolina, presumably in 1856, is nearly identical to examples made almost forty years earlier by his master John Swisegood.