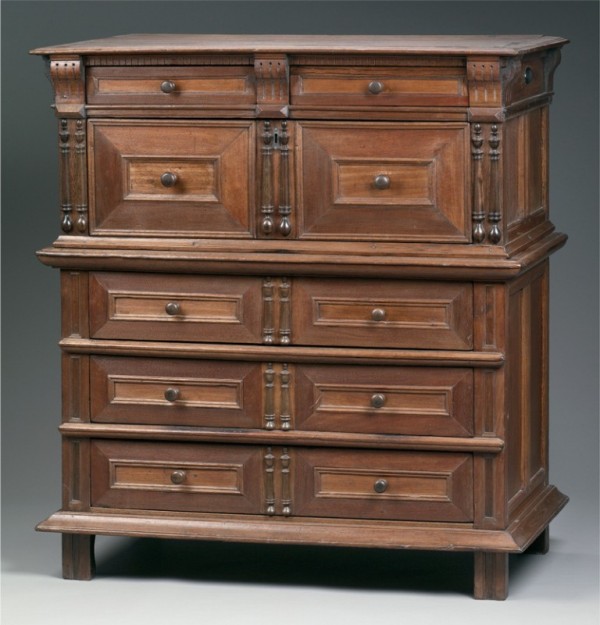

Chest of drawers with doors, Boston, Massachusetts, 1640–1670. White oak, red oak, chestnut, maple, black walnut, red cedar, cherry, cedrela, snakewood, rosewood, and lignum vitae with red oak, white oak, and white pine. H. 48 7/8", W. 45 3/4", D. 23 3/4". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery, Mabel Brady Garvan Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

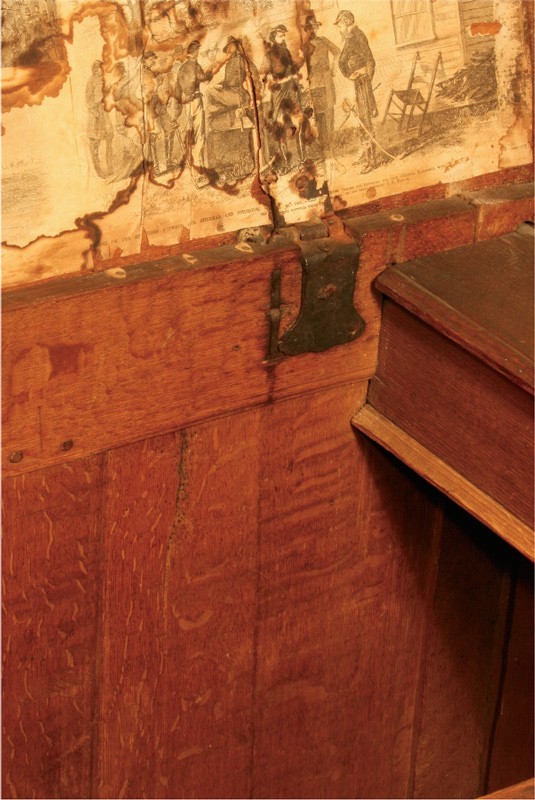

Detail of the chest of drawers with doors illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

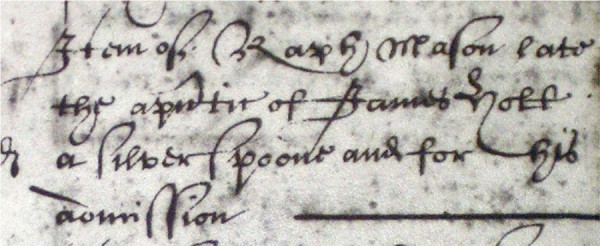

Admission record for Ralph Mason, Master’s and Warden’s Account Books, Worshipful Company of Joiners and Ceilers, London, 1621–1828. (Courtesy, Worshipful Company of Joiners and Ceilers, Surrey, England; photo, Peter Follansbee.)

Gravestone of Henry Messinger Jr., Granary Burying Ground, Boston, Massachusetts, 1686. (Photo, Peter Follansbee.)

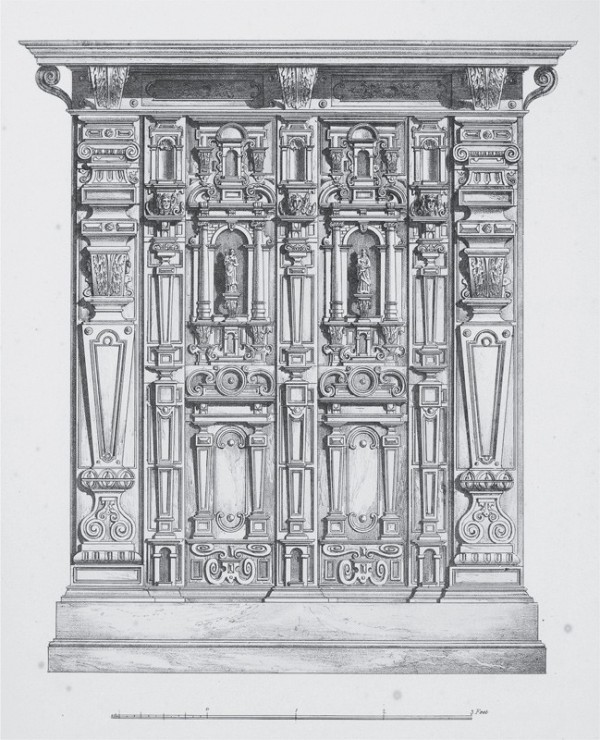

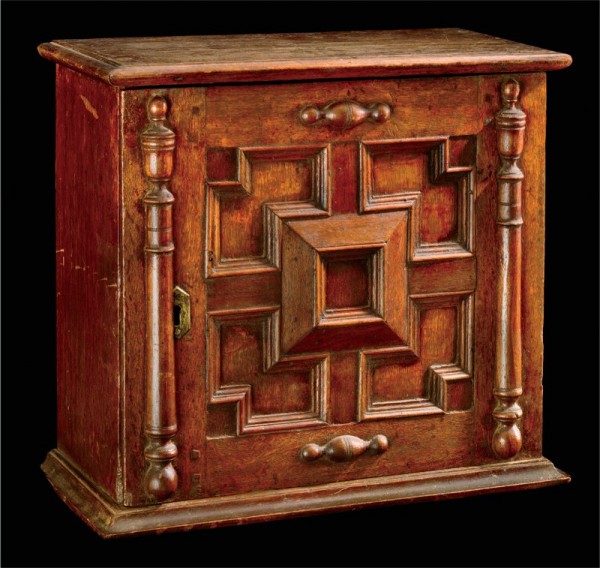

“An English Cabinet formerly the property of King Charles 1st at Theobalds,” from Charles James Richardson, Studies from Old English Mansions Their Furniture Gold & Silver Plate &c. by an Architect, 1st ser., 6 vols. (London: T. McLean, 1841–48), 1: pl. 19. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Printed Books and Periodicals Collection; photo, Jim Schneck.) The scale on the image indicates that the press is about five feet tall and probably was intended for books. The base appears to be a nineteenth-century addition. Originally there may have been a separate base or plinth.

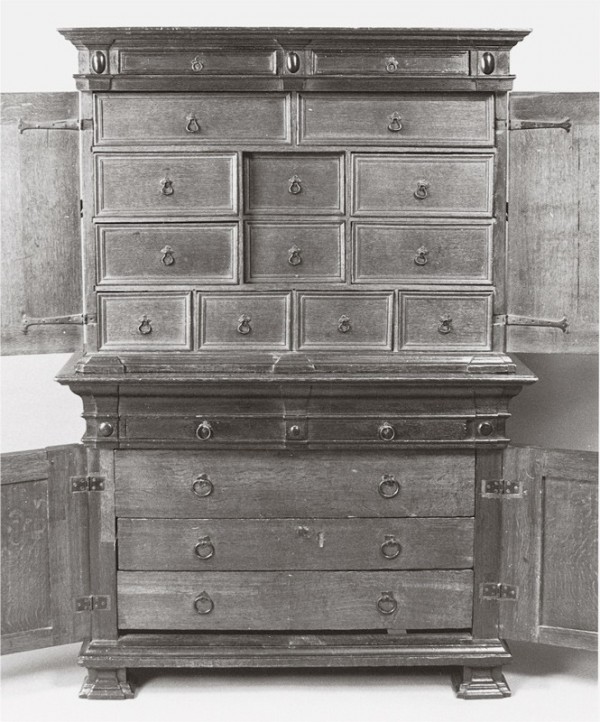

Cabinet and chest of drawers, London, England, ca. 1628–1630. Woods not recorded. H. 59 1/2", W. 41 1/2", D. 16". (Courtesy, Edwin Willson and David Gill, Mary Bellis Antiques, Hungerford, Berkshire.)

Interior view of the cabinet and chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 6. The upper section has a dovetailed board case, whereas the lower section has joined construction.

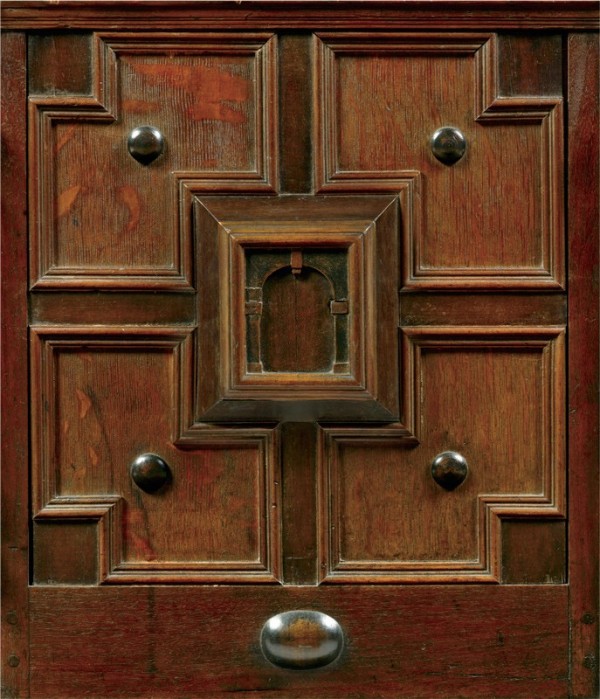

Chest of drawers with doors, London, England, 1650–1670. Oak, ebony, cocobolo (a pale tropical hardwood), mother-of-pearl, bone, and possibly ivory with unidentified secondary woods. H. 51 1/4", W. 46 1/2", D. 25 1/2". (Sotheby’s, A Celebration of the English Country House, New York, April 15, 2010, lot 43.) Several of the inlaid and ebonized oak plaques are missing, and the applied half-columns and feet are replacements.

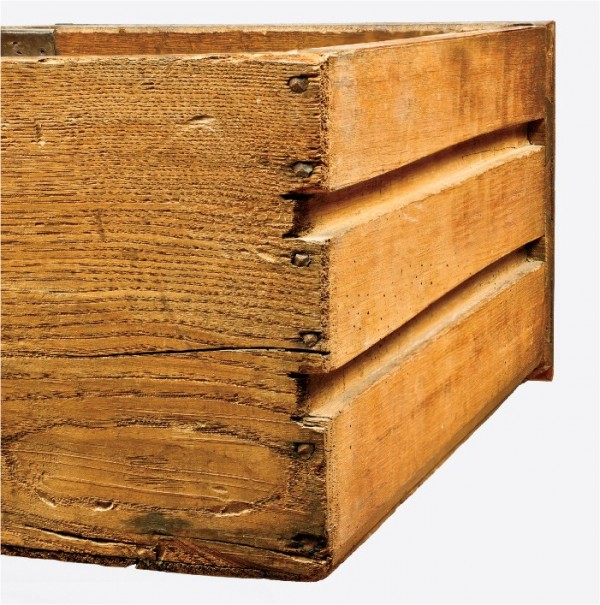

Detail of the chest of drawers with doors illustrated in fig. 8, showing evidence of riving on the interior of the upper case. Most of the framing members and some of the panels are made of riven lumber, while the drawer bottoms, rear panels, and the top of the upper case are made of sawn lumber.

Rear view of the chest of drawers with doors illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the drawer construction of the chest of drawers with doors illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The drawers are dovetailed at the front and nailed at the back.

Detail of the chest of drawers with doors illustrated in fig. 8, showing the lipped tenon on one end of the lower front rail of the lower case. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of lipped tenons on a chest with two drawers, Plymouth Colony, Massachusetts, 1650–1690. (Courtesy, Plimoth Plantation, Plymouth, Massachusetts.)

Detail of the chest of drawers with doors illustrated in fig. 1, showing the lipped tenon of the upper front rail of the lower case. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair attributed to Kenelm Winslow, Plymouth, Massachusetts, 1640–1660. Red oak. H. 42", W. 24", D. 15". (Courtesy, Pilgrim Society, Pilgrim Hall Museum, gift of Abby Frothingham Winslow, 1882.)

Detail of the back of the crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Peter Follansbee.)

Chest of drawers 1640-70. Boston, Massachusetts, United States. Oak, chestnut, cedrela, black walnut, and ebony with oak and white pine. H. 51 1/4", W. 47 3/16", D. 23 1/16". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, bequest of Charles Hitchcock Tyler.)

Cupboard with drawers, Boston, Massachusetts, 1670–1690. Oak, maple, walnut, cedar, and chestnut with oak and white pine. H. 55 5/8", W. 49 3/8", D. 21 3/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The frieze ornaments and the top of the upper case are restored on the basis of those elements on the chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 17.

Rear view of the cupboard with drawers illustrated in fig. 18. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the cupboard with drawers illustrated in fig. 18, showing the underside of the trapezoidal compartment in the upper case. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, Boston, Massachusetts, 1650–1690. Red oak, black walnut, red cedar, and maple with oak and white pine. H. 26 1/8", W. 47 5/8", D. 21 1/2". (Courtesy, Historic New England; photo, Richard Cheek.) The lower drawer, framework, and feet are missing.

Chest, Boston, Massachusetts, 1650–1690. Oak, cedrela, and walnut with oak and white pine. H. 30 1/2", W. 45", D. 20 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the scratch-stock molding on the interior of the chest illustrated in fig. 22. (Photo, Luke Beckerdite.)

Chest, Boston, Massachusetts, 1660–1690. Oak, walnut, and maple with oak. H. 19 3/4", W. 46 1/4", D. 20". (Private collection; photo, courtesy of the owner.) The chest is missing one or two drawers below the storage compartment. The lid is replaced.

Chest, Boston, Massachusetts, 1670–1690. Red oak and black walnut with white pine and hemlock. H. 36 1/4", W. 36 1/2", D. 21 1/4". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, 1909; photo, Gavin Ashworth/Art Resource, NY.)

Round leaf table, Boston, Massachusetts, 1660–1690. Oak, black walnut, cedrela, and maple with oak and white pine. H. 28 3/4", W. 29", D. 29" (open). (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The table is missing the molding around the lower shelf and its turned feet.

Round leaf table, Boston, Massachusetts, 1660–1690. Red cedar, cedrela and maple with oak and white pine. H. 33 1/4", W. 40 1/4", D. 20". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The top, feet, fly rail, and pendants are restored.

Square table, (oak table base), Boston, Massachusettts, 1650–1680. Oak. H. 27 7/8", W. 34", D. 34 1/8". (Collection of Shelburne Museum, gift of George G. Frelinghuysen II. 1965-336.8. Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The top and the bottom portions of the feet are missing.

Cabinet, Boston, Massachusetts, 1650–1690. Cedrela, chestnut, oak, ash, and cedar with white pine. H. 22 3/8", W. 32 5/8", D. 11 1/2". (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum, Nutting Collection; photo, Art Resource, NY.) Several moldings and interior drawers are replaced.

Cabinet, Boston, Massachusetts, 1660–1690. Mahogany and cedrela with oak and white pine. H. 18 5/8", W. 17 1/2", D. 9". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) One foot, several moldings, the edges of the bottom board, and the hinges are restored.

Cabinet, Boston, Massachusetts, 1660–1690. Oak, walnut, cedar, and lignum vitae with oak and white pine. H. 16 1/2", W. 16 1/2", D. 8 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the large and small applied half-columns on the chest of drawers with doors illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a panel on the chest of drawers with doors illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest of drawers, Boston, Massachusetts, 1690–1710. Cedrela with oak and white pine. H. 34", W. 33 1/8 ", D. 21 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest of drawers, Boston, Massachusetts, 1670–1700. Walnut with oak and white pine. H. 35 3/4", W. 37 5/8", D. 21 7/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 35, showing the hewing marks on the interior surface of a side panel of the upper case. (Photo, Luke Beckerdite.)

Chest of drawers, Boston, Massachusetts, 1670–1700. Walnut with oak and white pine. H. 35 3/4", W. 37 3/4", D. 23 1/8". (Private collection, photo, Mark HeVron.) This chest has all of its original hardware.

Detail of the chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 37, showing the spectral mortise on reused lumber. Reused lumber occurs on London case pieces but has not previously been recorded in Boston work.

Chest of drawers, Boston, Massachusetts, 1660–1700. Oak, black walnut, red cedar, maple, and possibly cedrela, with oak, chestnut, and white pine. H. 37 7/8", W. 39 1/2", D. 23 1/2". (Courtesy, Historic New England.)

Chest of drawers, Boston, Massachusetts, 1670–1700. Red cedar and possibly rosewood with oak and pine. H. 35", W. 38 5/8", D. 23 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The fronts of both case sections, the top of the upper case, and the larger and smaller moldings are made of red cedar. The chamfered edges of the cushion panel appliqués on the deep drawer are thick red cedar veneers. Because the maker intended to cover the drawer fronts completely with ornaments, he made the cores out of white pine.

Chest of drawers, Boston, Massachusetts, 1690–1720. Red oak, white oak, white pine, and yellow pine with red oak, white oak, and white pine. H. 40", W. 40 1/2", D. 22". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. J. Insley Blair, 1948; photo, Gavin Ashworth/Art Resource, NY.)

The joinery and turning traditions of seventeenth-century Boston are now perceived as central factors in the interpretation of seventeenth-century New England furniture, but before 1969, few scholars sought to identify specific schools of New England joinery. The few traditions that were identified, like that associated with Thomas Dennis of Ipswich, Massachusetts, were considered without reference to other schools of joinery. Through a revolutionary series of research initiatives and informed guesswork, furniture scholar Benno M. Forman developed a rationale for identifying the diagnostic traits of a Boston school of joinery and turning and suggested several probable makers. While subsequent scholars have questioned the dates assigned to certain objects and attributions to specific craftsmen, none has rejected Forman’s methodology.[1]

Assuming that the founders of the Boston tradition arrived on the Shawmut Peninsula in the late 1630s and began making furniture almost immediately, surviving objects suggest that these artisans and their apprentices made furniture in the London style for more than seventy years (figs. 1, 2). It is only logical to posit that there was significant development within this school and that immigrant craftsmen who arrived in that city after 1630 may have had an influence.

During the course of his research, Forman identified what appears to be the dominant school of London joinery from 1630 to 1670. To date, no English furniture scholar has significantly expanded on or refuted his work. While British furniture histories routinely illustrate joined chests of drawers with doors and profuse mother-of-pearl, bone, and exotic wood inlays, most English scholars have studiously avoided attributions. Among the most notable exceptions are Victor Chinnery and Adam Bowett. Chinnery’s “Laudian” school, along with a few surviving architectural fixtures and photographs of lost monuments like the interiors of Holland House published in Country Life, remains one the few irreducible groups of London joinery. Bowett has commented on the South American, Caribbean, and Asian hardwoods used on the façades of English chests of drawers with doors, but he too has refrained from attributing any of those objects to London. This reticence is puzzling, since London is, by far, the most likely center for the production of such early and stylistically elevated objects. Perhaps some English scholars still consider these chests of drawers with doors crude precursors of later Carolean veneered furniture rather than its immediate and necessary antecedent.[2]

This essay will review Forman’s attributions and key issues pertaining to the Boston school, some of which are in dispute. Among these are the identity and London origins of the makers, comparison between English chests of drawers with doors and a seminal American example, the use of exotic woods, and later manifestations of the Boston tradition. In some instances, we will be qualifying Forman’s assertions. In others, we will be amplifying his work, informed by objects that have appeared since his death in 1982.

The London-Trained Joiners of Boston

Publications on Boston furniture of the seventeenth century have focused on Henry Messinger and Ralph Mason as the principal joiners in that town. Both men had several sons who followed them in the trade, and Messinger’s daughter Sarah married Ralph Mason’s son Richard (1630–1674), who was also a joiner. Although these two families constituted a small joinery “dynasty,” several other woodworkers were active during the same period. The numerous chests, chests of drawers, and cupboards that survive in the “Boston” style are clearly from several shop traditions. Further evidence of a wide range of furniture forms exists in the probate records of Suffolk County. Linking these documents to surviving artifacts is difficult, and a further challenge is linking them to the artisans noted in period records.[3]

Many woodworkers identified in period documents left little if any evidence of their work. John Davis is the earliest joiner currently known to have worked in Boston. The principal record of him is a 1640 house contract between Davis and Samuel Dix mentioned in Thomas Lechford’s notebook. Davis was also mentioned in the Boston church records on February 1640/41.

Mrs. Anne Hibbon was excommunicated for her “irregular dealings with our brother John Davisse” in not admonishing him for overcharging, as she conceived it, and for her “causeless uncharitable jealousies and suspicions against him and sundry of the brethren that are joiners and other neighbors of the same calling as if they were of a combination.

Accusations regarding price fixing were common in Massachusetts after immigration ceased with the outbreak of the civil war in England.[4]

Apprenticeship contracts identify John Crabtree as another joiner working in Boston in the mid-1630s. Perhaps the most interesting records pertaining to him are suits for £20 in 1646 and £40 in 1648, both filed against Barbadian joiner Thomas Gray. These records indicate that Crabtree had business dealings in Barbados, which could be significant given the fact that imported woods are relatively common on early Boston chests and chests of drawers. Crabtree died in 1656.[5]

Boston joiner Thomas Scottow (1615–1661) was baptized in Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, England, on April 30, 1615. Presumably, he immigrated with his mother, Thomasine, and brother Joshua, who arrived in New England by 1634. Thomas would have been nineteen at that date, which was too young to have completed his apprenticeship according to English law. He could have begun serving his term in England and finished in Boston, or he could have served a shortened apprenticeship in New England. The earliest reference to Thomas working independently as a joiner is a 1638 deed.[6]

Attempts to curtail short apprenticeships in Boston began as early as June 20, 1660:

[It] is found by sad experience that many youths in this Towne, being put forth Apprentices to severall manufactures and sciences, but for 3 or 4 yeares time, contrary to the Customes of all well governed places, whence they are uncapable of being Artists in their trades, besides their unmeetness att the expiration of their Apprentice-ship to take charge of others for government and manuall instruction in their occupations which, if nott timely amended, threatens the welfare of this Towne.

[It] is therefore ordered that no person shall henceforth open a shop in this Towne, nor occupy any manufacture or science, till hee hath completed 21 years of age, nor except hee hath served seven yeares Apprentice-ship, by testimony under the hands of sufficient witnesses. And that Indentures made betweene any master and servant shall be brought in and enrolled in the Towne’s Records within one month after the contract made, on penalty of ten shillings to bee paid by the master att the time of the Apprentice being made free.[7]

Thomas Scottow remained in Boston until his death in 1661. His probate inventory listed a “chest of drawers” valued at £2, a “settle with drawers” at £1, a “chest” at £1.10, and several objects of presumably greater age, including a “Court Cubboard old cloth & cushion” valued at £1.10 and “5 old basse Chaires” at 8s. Among the tools inventoried in his shop were twenty-five planes, one “long saw,” three “hand saws,” one pair of compasses, three augers, two hold fasts, three benches, thirty-one chisels, two axes, one froe, and “files, & other tooles.” Scottow also had a “lathe and six turning tooles” in the cellar of his house, “parcels” of wood, “bolts & pannells” in the yard, and “lumber” and “boards” in his shop.[8]

John Scottow (1644–1678) followed his father in the joiner’s trade, but he was only seventeen when Thomas died. Presumably, he began training with his father and completed his apprenticeship with another master. Although John’s career may have spanned less than thirteen years, the fashionable furniture listed in his inventory—most notably the chests of drawers and leather chairs—and the high values assigned to the chest of drawers, tools, and materials in his shop suggest that he was among the upper echelon of Boston joiners:

2 boxes 6s and 1 Chest of Drawers 30 / £1:16:00

In the Garrett / 6 new frames 24s one Bedsteed 10 / one stand 5 /

In the west low roome 2 small tables 8 / 1 Chest 25 / £1:13:00

Linnen in sd Chest 9 napkins new 9s 1/2 doz (ditto) 4s Napkins 3s

1 tablecloth 6 towels 5s four pr of pillowbeers 16 / £1:17:07

5 Chaires 14s one Cradle 9s £1:03:00

In the East Low Room one Bed wth furniture & bedsteed cupboard, cupboard cloth and Cushion, £2:10:00

Chest of Drawers 30 / Square table 30 £3:00:00

9 Leather chaires £4/5 two Lookeing glasses 7s £4:12:00

At his Shop: 4 boxes 7 / three Chests 18s two bedsteeds 32s £2:17:00

1 Chest of Drawers £3:00:00

Boards, planks, timber & Joyners tooles £20:06:05[9]

“Ralph Mason, 35 yeres, Joyner” arrived in New England in July 1635, along with his wife, Anne, and their three small children. Immigrants had to swear an oath of allegiance to the crown and present proof of such conformity at the time of emigration. Ralph Mason’s certificate was from the “Ministr & Justice of peace of St Olives Southwarke,” a parish on the south bank of the Thames in London.[10]

Two records from the Worshipful Company of Joiners and Ceilers of London appear to refer to Mason. The first dates between June 12 and September 1, 1628—“Item [received] of Raph Mason late the apntice of James Holt a silver spoone and for his admission . . . [3s. 4d.]” (fig. 3)—and the second pertains to Mason taking an apprentice on the “Last Sept. 1628—Item of Raphe Mason for presenting Richard Praynte.” These are the only references to Mason that predate his immigration. Records for London apprentice bindings begin in 1621, but Mason’s indenture to James Holt (or any other joiner) is not among them. Judging by his age at the time he emigrated, Mason was a little older than usual when admitted to the Worshipful Company of Joiners and Ceilers. An Act touching divers orders for artificers, laborers, servants of husbandry and apprentices (1563) established guidelines for indentures, including the minimum age at which an apprentice could complete his term: “after the custom and order of the city of London for seven years at the least so the term and years of such apprentice do not expire afore such apprentice shall be of the age of 24 year.” It is noteworthy that Mason was allowed to take an apprentice shortly after being admitted to the Worshipful Company of Joiners and Ceilers. Most tradesmen were not allowed to take an apprentice until they had been freemen for three years.[11]

The earliest reference to Mason in New England is a February 19, 1637/38, grant for land in Muddy River, which is present-day Brookline, Massachusetts. The Shawmut Peninsula settled as Boston had already been divided into house lots by that date. In June 1658 Mason agreed to make furniture for the Muddy River town house as partial payment for additional land:

The Cedar swamp att Muddy river is lett to Ralph Mason his heyres and assignes for fifty yeares next ensuing, after the first of March next, in consideration whereof, hee shall pay yearly every first of March fourty shillings in wheate and pease proportionately; and hee is to pay fourty shillings this summer, and a fayre livery Cupboard for the towne house.[12]

Ralph Mason’s probate inventory, dated January 27, 1678, included a “parcel of old Joyners tooles” valued at 5s.; a “worke bench, 6 old plain stocks, 5 old plain Irons, one great piercer bit, 1 new narrow chizell, a bolting plain, a hatchet, 2 bookes, a jointer and iron and turning chizell in the custody of Samuel Mason” appraised at £1.17.3; a “cupboard” valued at £1.10; “some cross plains in the custody of Jacob Mason” appraised at 5s.; a “small table” valued at 2s.; “three old chairs and an old stoole” appraised at 2s.; and an “old chest, some tubbs & other lumber” valued at 12s. The low value assigned to these tools and the references to some being in the custody of Mason’s sons imply that he had either ceased or limited his joinery work.[13]

Ralph Mason’s four sons—Richard, Samuel, Jacob, and John—all became joiners. In 1660 the eldest, Richard (1630–1674), married Sarah Messinger. Richard probably trained with his father, Ralph, but the possibility also exists that he served his apprenticeship with Sarah’s father, Henry. Although New England apprenticeship contracts from this period are scarce, English records provide insights into prevailing customs. References to joiners apprenticing their sons to other woodworkers are common. Some families lacked the means to raise, educate, and train their children. In some English settings, civic or guild restrictions limited the number of apprentices a tradesman could have at one time, so if a joiner had two or more sons near each other in age, one might be bound to another craftsman. Last, sending a son to train with another craftsman might indicate a desire to align shops and dominate the joinery customs of their town.[14]

Richard Mason worked in Boston, presumably until he died in his mid-forties. His probate inventory, dated May 22, 1674, included the following:

One bedstead and curtains & chest drawers 02 :10 :00

One cabinet and couberd 01 :10 :00

One chest three Joynt stools & a tabell 01 :07 :00

One Box five chears & a cradle 00 :15 :00

Four playns 00 :12 :00

One chest and one coubard 03 :10 :00

Twenty two plates 00 :08 :00

A kneding trough & a lamp 00 :06 :00

A parcell of tools 01 :15 :00

Tow benshes 00 :02 :00[15]

Samuel Mason (1632–1691) was referred to as a “joiner” in a deed from 1671. Considering that he probably worked in Boston for almost forty years, he left little record of his trade. No probate records for him or his brother John (1640–1696) survive.[16]

Jacob Mason (1644–1694/95) married a woman named Rebecca in 1674. Forman noted that Jacob was called an “instrument maker” in Samuel Sewall’s diary, but that description could have meant many things. His February 16, 1694/95 probate inventory, compiled by Boston joiner John Nichols, listed furniture and some unspecified tools: “1 large cedar chest” valued at £1.10, “1 Case of Drawrs” at £1.10, “1 small Table & joint stool” at 5s., “5 old flagg Chairs” at 6s., and “Barrells, tubbs &,” “Timber,” and “Tooles” at £3.10.[17]

The earliest record for Henry Messinger (d. 1681) in Boston is a 1639/40 grant for land at Muddy River. His first child, John, was born in Boston on January 24, 1641. He and his wife, Sarah, remained there for the rest of their lives, eventually rearing eight children. Although several deeds refer to Messinger as a “joiner,” few documents pertaining to his trade are known. His tax rate was adjusted in 1645 in exchange for Messinger’s mending the schoolmaster’s fence. In 1661 he was called on to “secure ye foundation of ye Towne house from damage as also any other pt of ye house.”[18]

The first publication to draw attention to Henry Messinger was Esther Singleton’s Furniture of Our Forefathers (1913). She named several joiners found in period records and included information from Messinger’s will and that of his son Henry (1645–1686). Forman later asserted that Henry Sr., Ralph Mason, and John Davis were London joiners, but at present only Mason can be shown to have trained there. Since then other scholars, most notably Robert Trent, whose work built on what Forman had begun, have considered Messinger and Mason the two most important joiners in Boston.[19]

Henry Messinger Sr. and Ralph Mason are the first two joiners listed on the “Petition of the Handycraftsmen,” which was signed by 129 tradesmen and presented to the General Court in 1677. The petition requested protection from “the frequent intruding of strangers from all parts, especially of such as are not desirably qualified.” The petitioners—shoemakers, coopers, tailors, and joiners—felt that their livelihoods were being jeopardized by men who “never served any time, or not considerably for the learning of a Trade.” The placement of names on documents of this type was often hierarchical, suggesting that the other joiners who signed the petition deferred to Ralph Mason and Henry Messinger Sr. as leading artisans.[20]

The Messinger name is most common in the area around Wigton, Cumberland, England, yet no baptismal record for a child named Henry has been found. There are a small number of baptisms for Henry Messingers in other counties, but none can be linked to the Boston joiner. Similarly, the surname Messinger does not appear in the records of the Worshipful Company of Joiners and Ceilers of London between 1621 and Henry’s arrival in New England.[21]

Henry Messinger’s probate inventory, dated April 30, 1681, sheds some light on his success as a joiner (app. 1). He owned a variety of fashionable forms including leather chairs, upholstered (serge) chairs, elbow chairs, chests, and “a press cubberd wth drawers.” The listing for a “[family] cote of Armes & Joynrs Armes” valued together at 40s. is intriguing, since the “Joynrs Armes” could be those of the Worshipful Company of Joiners and Ceilers of London. In Messinger’s shop were “all sorts of Joyners Tools” valued at £5; a “table and Chest of Drawers not finished” appraised at £1; and “Timber within and without Doors wrought and unwrought” valued at £10. A “parcel of glue and Nurces skins” valued at £2.10 was in a chamber over the hall. This reference to sharkskin, which was used as an abrasive, is unique among New England inventories. André Félibien’s Des principles architecture (1st ed. 1676) notes the use of “sharkskin for polishing wood in irregular figures.” Some of the tropical woods found on seventeenth-century Boston case furniture have interlocked or “irregular” grain, whereas most of the native oak, cedar, maple, and walnut used during the period did not require the use of abrasives.[22]

When Henry Messinger died in 1681, his sons John, Henry, Simeon, and Thomas were all practicing joiners. Since John was born in 1641, he could have been working on his own from the early 1660s. Thomas’s career could not have overlapped that of his father since he was born in 1662 and probably completed his apprenticeship circa 1683. The most detailed document concerning John Messinger’s work is a court case involving ship captain William Hudson. In 1676 John’s apprentice Ebenezer Ingoldsby provided testimony regarding woodworking projects ranging from joined forms to oven lids and beetles. Born in Boston in 1656, Ingoldsby was nearly twenty when he appeared before the court and nearing the end of his term. Deeds from the mid-1680s describe him as a joiner, but his name does not appear in any other Boston records.[23]

Henry Messinger Jr. died on November 17, 1686, at the age of thirty-two (fig. 4). His will, which refers to Benjamin Threeneedle as his “eldest apprentice,” indicates that he had two apprentices at that date. The inventory of his shop listed “Timber, Boards, planks [and] workeing tooles . . . [appraised] by Mr Cunnibell and Tho: Warren, Joyners At Eleven pounds 16/8 . . . [and] A parcel of glew -12-10.” Henry’s wife reported “Money [received] since the death of my husband for worke done for Some Frenchmen 2-05-00.”[24]

Simeon Messinger (1645–ca. 1695) and Thomas Messinger (1661–d. after 1697) left little written record of their careers. A 1676 deed referred to “the shop that Simeon Messneger ye joyner works in at the further end of ye Garden . . . facing and fronting to ye Streete going from-ward ye Town house toward ye Prison in Boston . . . not the part toward Jeremiah Bumsteads.” The only record pertaining to Thomas Messinger’s work is a November 24, 1691, receipt totaling £1.7.8 for making the window shutters on the first Anglican meetinghouse in Boston.[25]

David Saywell (d. 1672), who may have been from Salisbury, Wiltshire, England, first appeared in Boston records in 1660, when he married Abigail Buttolph. He was subsequently mentioned in several deeds, one of which involved local turner Thomas Edsall. As was the case with John Davis and Thomas Scottow, Saywell worked in Boston only a short time. Nevertheless, he appears to have flourished in the joiners’ trade. His inventory listed a cupboard valued at £5 along with “New bedsteeds,” “24 paire of iron screws & nuts” (possibly for the bedsteads), “joint stooles chaire frames,” two chests, three tables, two desks, two boxes, two cabinets, and “some new worke in the shop not finisht.” His timber, lathe, benches, tools, and material were appraised at nearly £20.[26]

Jeremiah Bumstead (Bumpstead) (1636–1709) was born at Bury St. Edmunds, SuVolk, England, in 1636, immigrated to New England with his parents by 1640, and relocated to Boston shortly thereafter. He probably trained in Boston, but his master has not been identified. Bumstead married Hannah Odlin before 1664, when their first child was born. He was described as a “joiner” in Suffolk County deeds between 1669 and 1704. Several of these records reveal that Bumstead owned property next to that of Henry Messinger Sr. The two men apparently had a tumultuous relationship, since “Thomas Varrin, aged about 16 years . . . [testified] That he has heard Jerimyah Bumstead caull henery Messinger senior a wicked base mallitious fellow and . . . a prateing Logarhed.” In 1685 Bumstead was allowed to “sell beere & Cyder by retayle, in consideration of the wounds & lamnesse he receaved in ye time of the Indian warr.” Forman assumed that Bumstead’s career as a joiner was over at that point, but subsequent references to the latter as a “joiner” suggest that was not the case. Bumstead’s sister Mercy married Boston joiner John Roleston.[27]

John Cunnable (1649/50–1724) was described as a “Citizen and Joyner of London” in a debt record for £48 owed to ironmonger John Russell and recorded there in November 1673. That debt was still outstanding when Russell filed suit in Boston thirty-six years later. Cunnable arrived in New England shortly after 1673 and lived in Boston for most of his life. Judge Samuel Sewall mentioned work done by Cunnable including making a window and stairs for the former’s house in the 1690s. Cunnable died in April 1724. His inventory listed “1 Oval table” valued at 25s., “1 Square ditto” at 15s., “1 Case of Draws” at 50s., several “Strait Slate chairs,” “five back’d Ditto,”and “1 Arm’d Ditto.” Tools were not included, having been bequeathed to his son Samuel (1689/90–1746). The younger Cunnable and his son Samuel (1717–1797) were both called “housewright” and “joyner” in contemporary records.[28]

Benjamin Thwing (1619–1672) arrived in Boston in 1635 as a sixteen-year-old servant to his sister’s husband, Ralph Hudson, a woolen draper from Yorkshire. In 1638 Hudson left Thwing £10 in his will, stating that it should be paid “when [the latter’s] time should be out.” Thwing must have served the remainder of his apprenticeship with a joiner, but his master’s identity remains a mystery. A 1670 deed between Thwing and his son Benjamin (1647–1680) refers to the elder man as a “joiner” and the younger as a “carpenter.” Another son, John (b. 1644), married Maria Messinger, daughter of Henry Messinger Sr., but there is no evidence that the former worked in the joinery trade. Benjamin Sr.’s inventory included “One Cheste 6s; one meal trough 1s; one Livery cup board not finished 5s; two chairs 3s; one small table one box 6s.”[29]

The lack of detailed records for Bumstead, Cunnable, and Thwing suggests that in the Boston joinery trade they were less influential than David Saywell, Thomas and John Scottow, Henry Messinger Sr. and Jr., and Ralph Mason and his sons. There were many other furniture makers working in Boston during the seventeenth century of whom even less is known. Forman recorded more than one hundred joiners as well as turners and cabinetmakers, the latter beginning with John Clarke in 1681. As the seventeenth century drew to a close, furniture forms began to change in Boston, and other areas of New England followed. John Cunnable’s architectural work may reflect that shift, particularly if he was unable to adapt to new styles and methods of furniture construction.[30]

The London-Trained Turners of Boston

Turning was an important facet of the furniture-making trades in seventeenth-century Boston. Much of the applied ornament on early Boston chests and cupboards—pillars, half-columns, feet—is turned, and some of it represents the work of specialists who sold piecework to joiners, chair makers, master builders, shipwrights, and others. The most common work probably consisted of woodenware and nautical components like blocks and pulleys.

London court records from the early 1630s outline demarcations between the trades of joiners and turners in that city:

[The] Compy of Turners be grieved that the Compy of Joyners assume unto themselves the art of turning to the wrong of the Turners. It appeareth to us that the arts of turning & joyning are two several & distinct trades and we conceive it very inconvenient that either of these trades should encroach upon the other and we find that the Turners have constantly for the most part turned bed posts & feet of joyned stools for the Joyners and of late some Joyners who never used to turn their own bedposts and stool feet have set on work in their houses some poor decayed Turners & of them have learned the feate & art of turning which they could not do before. And it appeareth unto us by custom that the turning of Bedposts Feet of tables joyned stools do properly belong to the trade of a Turner and not to the art of a Joyner and whatsoever is done with the foot as have treddle or wheele for turning of any wood we are of the opinion and do find that it properly belongs to the Turner’s and we find that the Turners ought not to use the gage or gages, grouffe plaine or plough plaine and mortising chisells or any of them for that the same do belong to the Joyners trade.

Outside London, the same craftsman often performed turning and joinery. Thomas Quilter of Great Dunmow “[combined] the twin crafts of joiner and turner” and divided “his ‘working tools’ equally between his two sons, giving each “a turning lathe and a grindstone unhanged.” Quilter directed that his “elder son is to have the larger grindstone if he will teach his brother joining and turning in the best manner he can.”[31]

In Boston some joiners, like Scottow and Saywell, owned lathes and did their own turning, whereas others commissioned piecework from specialists or had a professional turner working in their shop. Presumably, joiners working in the London style would have patronized turners working in the London style. Assuming that a joiner trained in a city where the two trades were separate, he might not have known how to turn.

Thomas Edsall has been described as one of the earliest turners in Boston and credited for providing piecework for the Mason-Messinger shops. Forman did not cite but must have used Charles Pope’s Pioneers of New England as a source in creating Edsall’s biography. According to Forman, Edsall was forty-seven when he sailed from London onboard the Elizabeth and Anne in April 1635; however, the name on the passenger list is “Thomas Hedsall,” and there is no further reference to an “Edsall” or “Hedsall” until Thomas Edsall married Elizabeth Ferman in Boston in 1651 or 1652. Genealogist Robert Charles Anderson subsequently concluded that “Hedsall” and “Edsall” could not have been the same man, based on the unlikely circumstance that a man who left London in 1635 could have lived in Boston for nearly sixteen years without having been mentioned in records. As further evidence, Anderson noted that this immigrant would have been sixty-three when he married, and that the “Thomas Edsall” who married Ferman was mentioned frequently in the town records after 1652.[32]

Forman speculated that Thomas Edsall was either the brother or the son of London turner Henry Edsall, who took his first apprentice in 1627 and served as warden and master of the Worshipful Company of Turners in the 1650s and 1660s, but there is no concrete evidence to substantiate that claim. Moreover, several men with similar last names are mentioned in seventeenth-century English records, as is the case with Henry (b. 1619) and Thomas (b. 1612) Edsall of Sunninghill, Berkshire. Until further evidence comes to light, Forman’s assertion that Thomas Edsall was “unquestionably the most important turner” of his era in Boston and subsequent eVorts to link him with the Messinger and Mason shops must be discounted.[33]

The most detailed record pertaining to Edsall’s work in Boston is a court ruling against Henry Harris, who may have been an apprentice who ran away or a journeyman who owed Edsall work. As Forman noted, this document provides insight into the amount of work a tradesman was expected to produce per week:

According to a covenant . . . dated the 19th day of March, 1666/7 . . . I judge and order the said Harris either to dwell with & serve the said Edsell eight whole weeks beginning on the 17th Day of this June [1672] & to make every of the said weekes fifteen chair frames [illegible] good and merchantable or else shall make one whole hundred and twenty such frames in the whole eight week [illegible] the said Edsell finding & allowing unto him the said Harris sufficient place, tooles & stuff to make them.

Later in 1672 Harris won a suit against Edsall, receiving £12.4.7.[34]

Another turner identified by Forman was Nathaniel Adams Sr., who died in Boston in 1675. Adams’s inventory shows that lathe work for furniture (fifteen new chairs and forty-eight unbottomed chairs) accounted for only a small percentage of his shop’s production and sales. As yet, there is no documentation that Nathaniel Adams Sr. was associated with any of the joiners mentioned in this study.[35]

The London Chest of Drawers

How Forman arrived at the conclusion that London joinery and London-trained joiners were the source for the archetypal Boston seventeenth-century chest of drawers is not entirely clear. He was impressed with the dovetailed drawers of Boston case pieces and their strong resemblance to those of English chests and cognizant of a 1632 London lawsuit between that city’s joiners and carpenters restricting dovetailing to the former trade. Forman’s research on sixteenth- and seventeenth-century immigrant woodworkers in London showed that many of those craftsmen resided in Southwark, across the Thames from the city’s center. He also demonstrated that foreign artisans who specialized in making inlaid gunstocks and sword hilts produced similar ornament for London chests and cabinets. Forman eventually concluded that all case pieces with this class of ornament were from London and that the city’s joiners literally invented the chest of drawers.[36]

The latter theory may not be entirely correct. A group of northern Italian chests of drawers referred to as canterali in Genoa during the period are usually dated 1580–1620, although Italian furniture scholars have not provided substantial documentation for that range. “Virtuosos,” or connoisseurs, at the Stuart courts who traveled to Italy may have introduced the idea of a chest of drawers as a specifically Italianate furniture form. No English versions of these heavily carved canterali are known, but a few English patrons commissioned copies of Italianate sgabello chairs for grottoes from London craftsmen.[37]

The earliest English object resembling a chest of drawers with doors belongs to a small group of courtly cabinets made for the uppermost echelons of the Carolean court. Referred to as the “Laudian” school by Victor Chinnery, these cabinets have dovetailed cases filled with small boxes or drawers and doors with large appliqués that form niches with pediments, a conceit popular throughout Germany during the period. Among the better-known members of this school are a cabinet made for William Laud during his tenure as bishop of London between 1628 and 1633 and a press owned by Charles I (fig. 5). Paneling in the Jerusalem Chamber at Westminster Palace, commissioned by Laud from London joiner Adam Brown in 1629, is also in the same style. The most pertinent object of the Laudian school is a case piece composed of a cabinet over a chest of drawers with doors (figs. 6, 7). The cabinet and chest sections are shallow, and the wide drawers in the lower case were obviously intended to hold rolled-up deeds and other large legal documents rather than textiles. Some scholars have posited that the chest dates later than the cabinet. While differences between the two sections are apparent, their ornamental details are similar. This suggests that the chest section was commissioned within a few years of the cabinet, if not contemporaneously, and that furniture forms close to a chest of drawers were being made in London by the early 1630s.[38]

Some scholars have questioned the earliest dates assigned to seminal Boston chests like the example illustrated in figure 1. Their criticism was based largely on London chests of drawers with bone and mother-of-pearl inlay, many of which bear dates ranging from 1647 to 1663 on the ornament (fig. 8). Although those dates are useful in determining when such inlays were fashionable, they provide no benchmark for determining when London joiners began making chests of drawers. Court documents published by Forman support the use of chests of drawers in that city by 1638. Before sailing from London to take his post as the president of Harvard College, Rev. Joseph Glover commissioned a lavish set of household goods. He died on the voyage, and his widow, Elisabeth, married the new president of Harvard College, Henry Dunster, soon afterward. Years later, Glover’s heirs sued Dunster for bequests and residues from their parents’ estates. Part of the case centered on furnishings that were in Mrs. Glover’s house in Cambridge before her second marriage. Testimony offered by a maid who worked in the Glover household in 1638 referred unequivocally to textiles that were stored in a chest of drawers, which presumably accompanied the Glovers on their voyage to New England. The earliest reference to a chest of drawers in London is the 1640 inventory of alderman Anthony Abdy, who had one example in a chamber over the hall and another in the chamber over the parlor. Chests of drawers first appear in Boston inventories in 1643. In that year, appraisers valued an example owned by the late John Atwood at £3.1, a considerable sum. Other early references to chests of drawers are found in the inventories of London merchants who settled in New Haven in Connecticut, where London-trained joiners also worked. The 1647 inventories of Thomas Gray and Francis Brewster each listed a chest of drawers. Similarly, Stephen Goodyear, one of the London merchants who founded New Haven, died in 1658 owning two chests of drawers, one of which was described as “old.”[39]

The Boston Chest of Drawers

Wood extraction and preparation are significant factors in evaluating London-style joinery and its Boston derivatives. Forman believed that the Shawmut Peninsula was largely deforested in the early seventeenth century, owing to the Native American practice of burning undergrowth to facilitate hunting. That led him to conclude that Boston joiners, like their London counterparts, made furniture primarily from imported wood, which they sawed into working dimensions. In reality, the acquisition and preparation of wood in both cities will not be fully understood until more London examples have been examined in detail. In London, where wood was at a premium, timber entered the city through various sources. Among these were the so-called wainscot fleets, which arrived from Scandinavia and northern Europe, once or twice a year, with cargoes of oak balks, joists, and planks. Some of this imported timber was sawn into boards in the Netherlands before being shipped to London, and some was imported in riven form as well. Once wainscot entered the London woodworking trade, it was either sawn or riven into usable sizes. In English urban centers, pit sawing appears to have been the most common means of processing wood. In the Netherlands, water- or wind-powered sawmills often took the place of pairs of sawyers. By contrast, riving involved cleaving ring-porous hardwoods radially, using wedges and beetles to section trunks and lighter froes and wooden clubs called mauls to split out smaller pieces. Riven stock is automatically aligned on the medullary ray plane, whereas sawn stock can be radial or transverse in orientation.[40]

Forman’s contention that London artisans worked exclusively with sawn stock is refuted by the chest of drawers illustrated in figures 8 and 9 and by records of riven timber for carpentry in that city’s marketplace (see app. 2). The question of how commonly riven wood was used in London joinery remains unclear. It is unlikely that the city’s joiners could have obtained unseasoned oak to rive, unless such wood was brought down the Thames from inland sources or via the sea from the West Country.

Although clearly based on London work, the Boston chest of drawers with doors illustrated in figure 1 provides little information regarding the extraction of its stock. The interior surfaces have been planed smooth, removing all evidence of pit sawing or riving. Although one might assume components oriented on the medullary ray plane were extracted by riving, that is not necessarily the case. The most significant attribute of radial stock is that it will not warp across its width. This is an important consideration in drawer fronts that are intended to receive applied ornament, because warping could promote loss. Stock aligned with the medullary ray plane is also preferable for drawer sides, which need to remain stable to avoid binding. While it is true that almost all riven oak is aligned with the radial or medullary ray plane, the same orientation can be obtained by quarter sawing.

London and Boston case pieces typically have wide, thin framing members and relatively small panels (fig. 10). The panels of London case pieces are sometimes made of multiple boards, a feature also seen in London-derived furniture from the New Haven Colony and kasten from New York. London-trained joiners may have used broad framing members to regulate the dimensions of panels. Wide, thin sections of clear panel stock were the most difficult components to produce, especially if extracted by pit or frame sawing. This problem would have been particularly acute in cities like London, where timber for furniture making was largely imported. As the stiles and rails of the chest of drawers with doors illustrated in figure 1 suggest, London-trained joiners in Boston continued using Old World techniques and modes of construction after they arrived in New England, despite having ready access to oak and other ring-porous hardwoods.[41]

In both the London and Boston joinery traditions, makers used half-blind dovetails to connect the drawer sides to the fronts and nails to secure the rear corners (fig. 11). The number of dovetails varies according to drawer height. Thus, shallow drawers often have only one dovetail, slightly larger drawers usually have two, and very deep drawers—presumably intended for table linens or seasonal storage of bedding—sometimes have three. Dovetailed drawers also appear in joined case pieces attributed to Braintree, Cambridge, and northern Essex County, but it is unclear if their dovetailing was influenced by Boston practice.[42]

Another feature shared by London case pieces and their Boston counterparts is an exceptionally thin top, which is set in a shallow rabbet (usually 1/4"–3/8" deep) in the cornice moldings of both one- and two-piece forms. In London such tops are often made from three boards. To reinforce the tops, makers often attached a strut to the front and rear rails below. Why London joiners used thin tops is a puzzle, since the savings in material was offset by the labor needed to saw or rive thin stock. Surprisingly, the chest of drawers with doors illustrated in figure 1 and a related chest of drawers (fig. 17) do not have fore-and-aft struts, whereas most other Boston joined case pieces do.

The lipped tenon found on some Boston case pieces is another feature seen in London work. In most cases, mortise-and-tenon joints are positioned in the stock so the rails and stiles are flush with each other. The archetypal London lipped tenon is positioned farther to the rear, thus setting the face of the rail ahead of the face of the adjoining stile. This feature seems to have evolved in order to place the front base molding ahead of doors (fig. 12). Another version of this lipped tenon has long been associated with the lower cases of chests with drawers and cupboards made in Plymouth Colony, Massachusetts (fig. 13), but on those objects the lipped tenon serves no apparent function. The Boston chest of drawers with doors has lipped tenons, but they are not in the same location as those on the London examples. Their use on the upper front rail of the lower case may have reflected the maker’s desire to position the large waist molding of the case forward of the doors (fig. 14). Further evidence that the lipped tenon is a London joinery detail can be found on an armchair that belonged to Edward Winslow (1595–1655) and is attributed to his brother, London-trained joiner Kenelm Winslow (1599–1672) (figs. 15, 16). On the chair, the tenons are cut in the top of the rear stiles and fit into mortises cut in the crest rail. Because the tenon extends up behind the crest rail and prevents wracking, it provides a measure of structural support.[43]

The large chest of drawers illustrated in figure 17 is the only other London-derived two-part chest of drawers from seventeenth-century Boston with three drawers in the lower case. Although similar in proportion, this object and the chest of drawers with doors (fig. 1) have structural differences critical to dating them. The interior surfaces of the chest are rougher, with marks left from riving, and the sides of its drawers are laminated (fig. 17). This could indicate that the maker had a shortage of wide riven stock, or that he was following the prevailing London practice of gluing up smaller-dimensioned materials to conserve wood. The chest also shares with other Boston case pieces the “paneling” of the front stiles (the chest of drawers with doors is an exception because the doors cover the stiles of the lower case). To render this detail, joiners planed channels with fine edge moldings along the entire length of the front faces of the stiles, then used mitered stops to create the illusion of panels. Several other eastern Massachusetts shop traditions used this technique, but only on drawer fronts. Much of the carcass of the two-part chest is made of riven cedrela (Spanish cedar), an imported wood often used for moldings, glyphs, and other appliqués; the rear framing members and the rails between the drawers are the only structural oak in the case. Except for the sides of the rear stiles, none of the oak shows in the finished object.

Other Furniture Forms Attributed to Boston

The cupboard illustrated in figure 18 is the only indisputable Boston example known, and contemporary London examples are rare. By 1670 cupboards were being displaced by chests of drawers, and the growing popularity of the latter furniture form explains why joiners began to install drawers in the lower cases of some cupboards. The Boston cupboard shares several traits with other London-derived case pieces, including a strut under the top boards of the upper case, dovetails at the front corners of the drawers, and large, academically correct cove and Roman ovolo moldings. The cupboard deviates from conventional London and Boston practice in having elaborate applied ornament on the sides of the lower case and is unique in its use of ebonized curly maple to simulate a tropical hardwood.[44]

The maker of the Boston cupboard used different methods to enclose the rear of the two case sections (fig. 19). The rear of the upper case has a large pine panel with feathered edges that engage grooves plowed on the inner edges of the four framing members. The rear of the lower case has three vertical boards that meet in lap joints and feathered edges that are set in grooves in the vertical framing members and nailed into rabbets in the horizontal framing members. Another distinctive feature involves the framing of the trapezoidal compartment (fig. 20). Rather than attaching the rails of the compartment to the rear posts with mortise-and-tenon joints, the maker merely nailed them in place from behind. This is substandard practice, considering the more normative use of pentagonal posts on Boston leaf tables with trapezoidal frames (figs. 26, 27).[45]

Although furniture scholars were not aware of the Boston cupboard during Forman’s lifetime, two chests with applied ornament on the front panels informed his theories. On the example illustrated in figure 21, two of the panels have crossets at the corners, and the third features a round motif with four circular, molded segments separated by voussoirs—a design common in London chests of drawers but unique in Boston work. The other chest (not illustrated) has three crosseted panels.[46]

Other chests that have appeared since Forman’s death shed additional light on Boston versions of that form. The example illustrated in figure 22 has an applied Roman ovolo above a false drawer and an ogee molding on the front edges of the lid and till. The bottom of the till protrudes past the interior side and is also molded (fig. 23). As is the case with the chest of drawers with doors (fig. 1), the interior surfaces of the chest are smooth and neat. The maker used planes and scrapers to remove all evidence of riving and/or sawing and scratch-stock cutters to produce the moldings on the framing members. A fragmentary Boston chest has a different ornamental scheme, featuring a crosseted panel in the center and side panels that are further accented with lozenge-shaped appliqués (fig. 24). Boston chests of this type are rare, which is surprising when one considers that the form is one of the most common in other New England joinery traditions.

Another curious furniture form from Boston is a narrow chest with drawers (fig. 25). Six examples with one or two drawers are known. Their proportions and design suggest that they were used as chamber tables or dressing tables. Their dovetailed drawer construction and applied ornament is squarely in the Boston tradition, and the example shown in figure 25 has applied half-columns similar to those on the lower case of the Boston cupboard (fig. 18). These case pieces may be antecedents for the numerous chamber tables with an open shelf beneath a case section that were made in several shops on the South Shore of Massachusetts.[47]

Two Boston leaf tables are extraordinary rarities within the surviving corpus of New England furniture (figs. 26, 27). Tables of this type appear to have been used initially for drinking wine or dining, rather than gaming. Celia Fiennes may have seen a comparable example when she visited Hampton Court in 1698. Her diary mentions a “Clap table,” which was the Dutch term for any folding, or leaf, table. The word “clap” obviously referred to the sound a leaf made when closed against the legs or frame. Fiennes also noted that the “back room” at Hampton Court contained “a little Wanscoate [oak] table for tea, cards or writeing.” This suggests that small tables, like the Boston examples, performed several functions, regardless of their shape or top design.[48]

The Boston table illustrated in figure 26 has an oak frame, a black walnut top, and walnut, cedrela, and maple applied ornaments. The sources for this furniture form in England are ambiguous, but Dutch leaf tables, which often have a draw leg or a hinged fly leg, may have been an influence. The fly legs on Dutch tables of this genre were generally turned from two pieces of laminated stock with a paper interface, then separated like the applied half-columns on case pieces; one half remained stationary, and the other half rotated out to support the leaf and back to abut its mirror image and create the illusion of a single turning. In contrast, almost all English examples are framed with an auxiliary post, or leg, and both Boston tables are constructed in that fashion. This required an extraordinarily thick rear rail in order to house the fly leg post when the tables are shut. Another interesting feature of the Boston tables is the pentagonal shape of the posts where the rails join to form trapezoids. This allowed makers to secure the rails to the posts at approximately ninety-degree angles.

Both of the Boston leaf tables are sophisticated in design and construction, which suggests a connection to the upper echelon of London’s joinery trade. They have dovetails at the front corners of their drawers and are composed of native and exotic woods. The table illustrated in figure 26 is the only Boston object with carved brackets, and its legs have multiple rings reminiscent of the “Ordre Français” designed by sixteenth-century French architect Philibert de l’Orme. The other table is even more architectural, having arches and classically correct Doric columns with pronounced entasis (fig. 27). It is made primarily of red cedar and cedrela with maple bosses and cedrela glyphs. The red cedar probably came from Bermuda or the Carolinas, whereas the cedrela came from the Caribbean. Extensive riving evidence on this table indicates that the cedar was treated like a ring-porous hardwood.[49]

A square table base formerly owned by pioneer collector Dwight Prouty (fig. 28) may also be a seventeenth-century Boston product. It is distinguished among early New England examples in having turned stretchers and is the earliest table from that region with bilaterally symmetrical balusters. Pinning evidence in the frieze rails indicates that the base probably had a multiboard, clamped oak top, much like those surviving on three other New England square tables. The posts and stretchers are approximately 2 5/8" square, and the rails are made of riven stock that tapers substantially across the grain. The maker used the thicker dimension at the top, since that was the pinning surface for the top boards. The brackets are integral with the rails and have ogees generated with scratch-stock cutters.

Two square tables currently attributed to Boston are later in date and have maple posts, dry-brushed grain painting, and single baluster turnings on the posts. Nevertheless, there seems to be a relationship between the turnings of all three objects. Heavy balusters with pronounced, filleted collarinos are relatively rare in New England turning, although they are common in the Middle Atlantic region and the South. This suggests that two different shop traditions used the same turner. The later tables have medial struts to support the top boards, much like those seen on seventeenth-century Boston chests of drawers.[50]

The cabinet was another form favored by Boston joiners working in the London style. The large example illustrated in figure 29 is the only Anglo-American example with two doors, and the only one to approach the size and architectural grandeur of its European prototypes (fig. 6). The strong horizontal emphases of the surbase and frieze and the lack of turned feet suggest that the cabinet may have been intended for use on a table or, perhaps, that it originally had a tall base resembling a table frame. Certainly the carrying handles on the ends suggest that it was moved on a regular basis, perhaps back and forth from a countinghouse to a sailing vessel.[51]

Two smaller Boston cabinets, possibly used for storing writing materials and implements, also survive. The example illustrated in figure 30 is extraordinary in being made of mahogany and cedrela. This object may be earlier than a Salem, Massachusetts, chest with a mahogany plaque bearing the date 1700, making the cabinet the earliest piece of American furniture with that wood. British and American one-door cabinets of this general type often have turned feet, but that was not the case with the Boston example illustrated in figure 31. It has an unusually elaborate door, with an oak panel and framing members and walnut and cedar appliqués. With its raised pyramidal mount, L-shaped plaques, and crosseted corners, this door would have been described during the period as having a “cushion” panel. Flanking the panel are applied walnut half-columns.

Use of Exotic Woods and Applied Ornaments

Forman was the first scholar to recognize the use of exotic woods in seventeenth-century Boston furniture. His research focused on cedrela, but many other exotic species have been identified since his death. Indeed, several scholars have noted that black walnut, often referred to during the period as “Virginia walnut,” was regarded as an exotic in both England and New England because that wood was imported from the southern colonies. The same was true of cedar and cypress. In 1682 Thomas Ashe wrote that the Carolinas were “cloathed with odoriferous and fragrant . . . Cedar and Cyprus Trees, of . . . which are composed goodly Boxes, Chests, Tables, Scrittores, and Cabinets. . . . Carolina [cedar] is esteemed equal . . . for Grain, Smell and Colour . . . [to] Bermudian Cedar, which of all the West Indian is . . . the most excellent.”[52]

Exotic woods were commonly reserved for ornamental appliqués, like the exceptional Tuscan-Doric half-columns (fig. 32) on the Boston chest of drawers with doors (fig. 1). As is the case with many Boston half-columns, these have a pendant vase at the bottom and a turned urn at the top. A second type, exemplified by the half-columns on the lower case of the Boston cupboard with drawers (fig. 18), has an unconventional urn element. Whereas some Boston case pieces have appliqués made of exotic woods, others have half-columns, bosses, and other components made of maple and finished to resemble ebony. Mimicking exotics in that fashion was the norm in other eastern Massachusetts shops. In Boston case furniture, cushion panels and inset panels on drawers and stiles are often made of exotics (fig. 33). While some inset panels are plaques, others are thin enough to be considered veneer.

Exotics used in Boston furniture include black walnut, red cedar, cedrela, snakewood, rosewood, and lignum vitae. What is not clear is how those species arrived there. Boston merchants and timber dealers could have imported exotics circulating in the Dutch timber trade via London or acquired them directly from the Caribbean, through legitimate trade or through acts of piracy. Certainly New England merchants obtained large amounts of Spanish-American silver specie, through means both fair and foul. Further, New England shippers competed with Dutch carriers throughout the Atlantic and may have learned about cargoes of exotic woods in that manner.[53]

Several Boston chests are made of cedrela (fig. 34), and some hewing marks on the interior surfaces left by the enslaved, mixed-race logging crews who cut down the trees in the jungles of the Caribbean and Central America and squared them up into balks for export can still be seen (fig. 36). The Boston chest illustrated in figure 37 has such marks, but it is made of walnut and recycled oak, as witnessed by a spectral mortise pocket on the interior (fig. 38). Although a cousin of mahogany, some species of cedrela are ring-porous and suitable for riving. Cedrela’s popularity in the seventeenth century probably reflected its relative low cost, availability in wide widths, fine pore structure, and pale color. It also contrasted dramatically with darker woods, like walnut or rosewood, and ebonized surfaces.[54]

A black walnut chest of drawers that descended in the Pierce family of Dorchester has moldings of maple, red cedar, and possibly cedrela (fig. 39). It is identifiable in inventories extending back to the original owners and is one of the few Boston case pieces known to have descended in a family from near that city. The wood generally referred to as “red cedar” in descriptions of seventeenth-century Boston furniture is actually a juniper. The popular name refers to either Virginia red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) or Bermuda cedar (Juniperus bermudiana). The location where boards are taken from a juniper trunk determines whether those boards are clear or exhibit tiny knots. Most commercially available red cedar today is relatively free of such knots and seems to come from the lower portions of large trees that grow in mountainous areas. By contrast, the red cedar used in most early American furniture is rife with small knots. Much of that wood may have come from the lowlands of the Carolinas or Florida. Less plausibly, some of the timber used in Boston may have come from Bermuda, although wood shortages in seventeenth-century Bermuda make that scenario less likely.[55]

English observers were well aware of exotic woods, often noting their use in architecture. In 1698 Celia Fiennes wrote:

I went to admiral Russells [house] who is now Lord oxfford . . . The hall . . . its wanscoated wth wall Nutt tree, the pannells and Rims round wth mulberry tree yt is a Lemon Coullour, and ye moldings beyond it round are of a sweete outlandish wood not much differing from Cedar but of a finer Graine, the Chaires are all the same [wood].

Much of the cedar described in period documents appears to have been red cedar from the American South or Bermuda, rather than Atlantic white cedar. The fourth edition of John Evelyn’s Sylva: A Discourse of Forest Trees & the Propagation of Timber (1706) provides one of the best period accounts of woods used for furniture and architecture. In reference to cypress, he stated:

Since these precious materials may now be had at such tolerable rates (as certainly they might from Cape-Florida, the Vermuda, or other parts of the West-Indies) . . . I cannot but suggest that our more wealthy citizens of London, every day building and embellishing their dwellings, might be encourag’d to make use of it in their shops, at least for shelves, counters, chests, tables, and wainscot, &c the fancerings (as they term it) [veneering?] and mouldings, since beside the everlastingness of the wood, enemy to worms, and those other corruption we have named, it would likewise greatly cure and reform the malignancy and corrosiveness of the air.

Regarding red cedar, he wrote:

After all these exotics brought from our plantations, answering to the name of cedar, I should esteem that of the Vermuda, little inferior, if not superior, to the noblest Libanon, and next, that of Carolina for its many uses, and lasting . . . the natural, wholesome, and ancient use of timber, for the more lasting occasions, and furniture of our dwellings; And though I do not speak all this for the sake of joyn’d-stools, benches, cup-boards, massy tables, and gigantic bed-steads, (the hospitable utensils of our fore-fathers) yet I would be glad to encourage the carpenter, and the joyner.[56]

The Boston leaf table and two-part chest of drawers illustrated in figures 27 and 40 are exceptional in having red cedar primary woods. The chest is further distinguished by having contrasting plaques made of rosewood or some other dense, dark tropical hardwood. The plaques are set in recesses cut in the front stiles and drawer fronts.[57]

Later Boston Furniture in the London Style

The latest manifestations of Boston joinery in the London style appear to have been coeval with the dovetailed-board, veneered case pieces of the baroque, or “William and Mary” style, and include chests of drawers, chests with drawers, and chamber tables (fig. 41). Many of these case pieces lack dovetails, are made principally of softwoods, and have extensive painted decoration. Some scholars have been reluctant to attribute these objects to Boston because of the lack of dovetailed drawers, but the high correlation of other shared traits suggests that they are Boston products, and that many date from the eighteenth century. Although genealogical research has called into question attributions made by Forman and some of his students to specific makers and shop traditions, their observations pertaining to the overall school of Boston joinery remain largely valid. Undoubtedly, more objects by this school of joinery and turning will emerge, and further documentary work in England may clarify the origins of Henry Messinger and other important artisans.[58]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article, the authors thank Gavin Ashworth, Luke Beckerdite, Paul Beedham, Kathryn Bolles, Dennis Carr, Katherine Chabla, Victor Chinnery, David Gill, Constance Godfrey, the late Dudley Godfrey, Joseph P. Gromacki, Erik Gronning, Peter Kenny, Robert Leath, Susan Newton, Martin O'Brien, Jonathan Prown, Helena Richardson, Harry Mack Truax II, John and Marie Vander Sande, Nancy Sazama, Gerald Ward, and Edwin Willson. We are particularly grateful to Alan Miller and Adam Bowett for reading the manuscript and providing helpful suggestions and references.

Appendix 2

Timber in London Records

The 1607 bylaws of the Company of Carpenters provide information on various timber components used in the city. Although these specifications pertain to the building trades, they show some of the types of timber that were available in London during the seventeenth century. The quarter-boards (not the “quarters” or the “double-quarters”) and the “seelinge-boards” were tapered in thickness. This most likely resulted from their having been radially riven from ring-porous woods such as oak.

The Master and Wardens, or three of them . . . to make search in all places within the limits, for & upon timber, boards, planks, rafters, joists, quarters, laths, & other things belonging to carpentry, to be sold; to try & see that the same should contain the just length, measure & assize following, that is,

Every load of timber hewed or sawn to contain in measure of solid timber fifty foot of assise, and every tunne of such timber, 40 ft. of assisse, under a penalty of 2s6d for every load or tunne put to sale contrary thereto.

Every load of rafters to contain in number 30 rafters, each rafter 12 ft. of assisse in length at least; and at the greater end in breadth, 4 inches & 1/2 an inch, and in thickness, 4 inches; and at the lesser end in breadth, 4 inches, and in thickness, 3 inches at least, under a penalty of 2 pence for every rafter.

Every load of joists to contain in number 30 joists, every joist to be in length 8 ft. 6 inches of assise, in breadth 6 inches, and in thickness 4 inches from end to end at the least, under a penalty of 2 pence for every joist.

Every load of puntions, being of oak to contain 40 puntions, every puntion to be in length 6 ft. 6 inches, in breadth 6 inches, and in thickness 4 inches. Every load of puntions being of beech, to contain 50 puntions, every puntion to be in length 6 ft. 6 inches, and 5 inches square, under a penalty of 2 pence for every puntion.

Every load of bedsides to contain 50 bedsides, every bedside to be in length 6 ft. 6 inches, in breadth 10 inches, and in thickness 2 inches, under a penalty of 1 penny for every bedside.

Every load of double quarters to contain in number 50 double quarters, to be in length 8 ft. 6 inches, in breadth 4 1/2 inches, and in thickness 3 inches from end to end at least.

Every load of single quarters to contain 100 single quarters, each quarter to be in length as the double quarters, in breadth 3 1/2 inches, and in thickness 2 inches from end to end at the least, under the penalty of 1 penny for every double quarter, and 1 halfpenny for every single quarter.

Every load of stable planks to be 40 planks, each plank to contain in length 6 feet 6 inches, in breadth 12 inches, and in thickness 2 inches, under a penalty of 1 penny for every plank.

All quarter-boards to be at the thinner edge the 3rd part of an inch in thickness, and at the thicker edge 1 inch, under a penalty of sixteen pence for every hundred quarter boards.

All seelinge boards to be thicker at the edge half an inch, and at the thinner edge the 3rd part of an inch, under a penalty of sixteen pence for every hundred seeling boards.

All planch boards to be in thickness an inch, under a penalty of sixteen pence for every hundred planch boards. All planks and boards to be measured & accounted after the rate of 5 score ft. of plank or board to the hundred, flat measure, being duly measured without fraud, according to the plain superficies, what length, breadth, or thickness soever may be.

All laths to contain in thickness at either end the 3rd part of an inch, and in breadth from end to end an inch & a half, or very little less, and all laths to be in length 5 ft. or 4 ft. of assise, and them of 5 ft. long to be accounted 5 score laths to every bundle, and them of 4 ft. long to be accounted 6 score and 5 laths to every bundle; 30 such bundles to be a load, being 20 bundles of them at least hart lath, and the shorter not to be packed or bound up with the longer, under the penalty of 4 pence for every bundle.

. . . if any of the Master or Wardens should find any such stuff belonging to the occupation of Carpentry to be bought between forraine and forraine contrary to the liberties of the city, the Master & Wardens to have power to seize the same. . .

. . . all manner of wayny pieces of timber that should arise out of the premises & be serviceable, there should be allowed two for one, or three for two or otherwise, as should be indifferent between buyer & seller.

Source: E. B. Jupp, An Historical Account of the Worshipful Company of Carpenters (London: Pickering & Chatto, 1887), pp. 145–52.

Benno M. Forman, “Urban Aspects of Massachusetts Furniture in the Late Seventeenth Century,” in Country Cabinetwork and Simple City Furniture, edited by John D. Morse (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1970), pp. 1–34. Benno M. Forman, “Boston Furniture Craftsmen, 1630–1730,” MS, Winterthur, Delaware, 1969, in the possession of Robert F. Trent. Benno M. Forman, “Continental Furniture Craftsmen in London: 1511–1625,” Furniture History 7 (1971): 94–120, pls. 25–28. Benno M. Forman, “The Origins of the Joined Chest of Drawers,” Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 31 (1981): 169–83. This article was republished with additions by Robert F. Trent, as Benno M. Forman, “The Chest of Drawers in America, 1635–1730: The Origins of the Joined Chest of Drawers,” Winterthur Portfolio 20, no. 1 (Spring 1985): 1–30. A summary of critiques of Forman’s last article can be found in Robert F. Trent, “Furniture in the New World: The Seventeenth Century,” in American Furniture with Related Decorative Arts, 1660–1830, edited by Gerald W. R. Ward (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1991), pp. 25–28 n. 8.

Adam Bowett, “The Age of Snakewood,” Furniture History 34 (1998): 212–25; Adam Bowett, “Myths of English Furniture History: Anglo-Dutch,” Antique Collecting 34, no. 5 (October 1999): 29–33; and Adam Bowett, “Furniture Woods in London and Provincial Furniture, 1700–1800,” Regional Furniture 22 (2008): 87–114. Victor Chinnery, Oak Furniture: The British Tradition (Woodbridge, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1979), pp. 432–37. For related architectural work, see Howard Colvin, The Canterbury Quadrangle of St. John’s College, Oxford (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), pp. 44–46, pls. 41, 42. In a later essay, Chinnery cited some 1598 furniture designs of Johann Jakob Ebelmann of Strasburg, Germany, as a potential source for the aediculae of door panels in the Laudian group. However, it is evident that such panels were prevalent throughout Germany, so the Ebelmann source need not be considered an immediate prototype. See Sotheby’s Concise Encyclopedia of Furniture, edited by Christopher Payne (New York: Harper Collins, 1989), pp. 50–52.

For previous attributions pertaining to the Messinger and Mason shops, see n. 1 above; New England Begins: The Seventeenth-Century, edited by Jonathan L. Fairbanks and Robert F. Trent, 3 vols. (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1982), 3: 522–27, 536–38; and Gerald W. R. Ward, American Case Furniture in the Mabel Brady Garvan and Other Collections at Yale University (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Art Gallery, 1988), pp. 125–28. Many upholstered chairs can be interpreted as seventeenth-century Boston work, but none has been linked to a specific joiner’s shop. In his unpublished manuscript “Boston Furniture Craftsmen, “Forman attempted to identify all the turners and joiners working during that period. Another invaluable reference is Annie Haven Thwing, Inhabitants and Estates of the Town of Boston, 1630–1800 and The Crooked and Narrow Streets of Boston, 1630–1822 (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society and Massachusetts Historical Society, 2001), CD-ROM. This essay will take a narrower focus, concentrating on new research on the Mason-Messinger tradition and other Boston shops that produced case furniture in the London style.