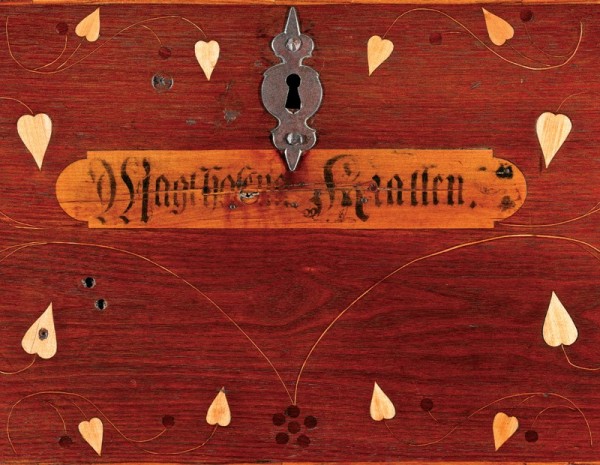

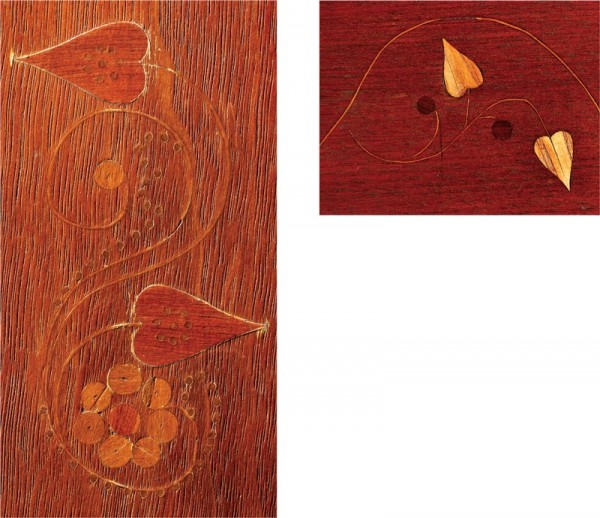

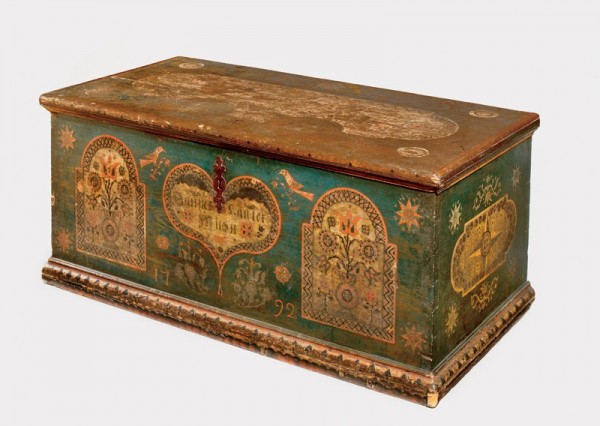

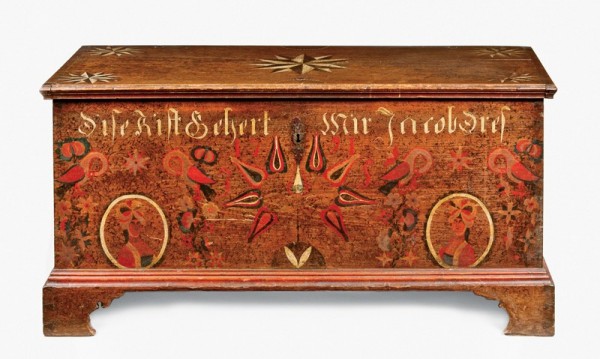

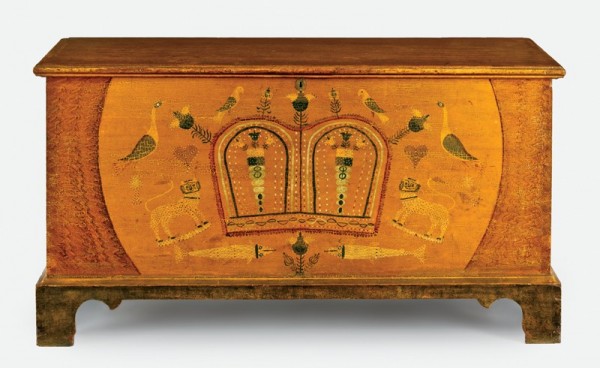

Chest, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1792. Walnut and mixed-wood inlay (including maple, sumac, holly, birch, and possibly mahogany) with white pine and oak; brass, iron. H. 27", W. 59 1/4", D. 24 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Laszlo Bodo.) The brasses are replaced.

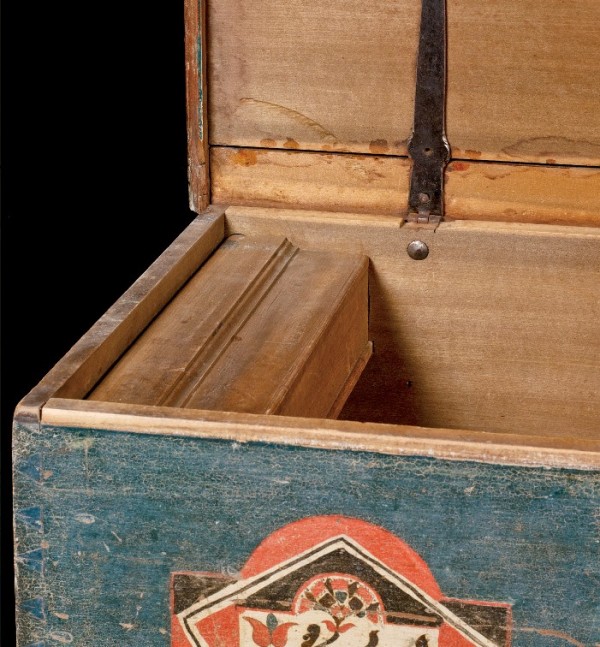

Detail of the interior of the chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.) The surviving till lid has a molded top and edge. Two large fraktur were once pasted to the underside of the chest lid.

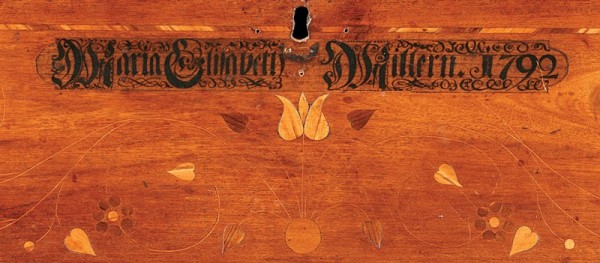

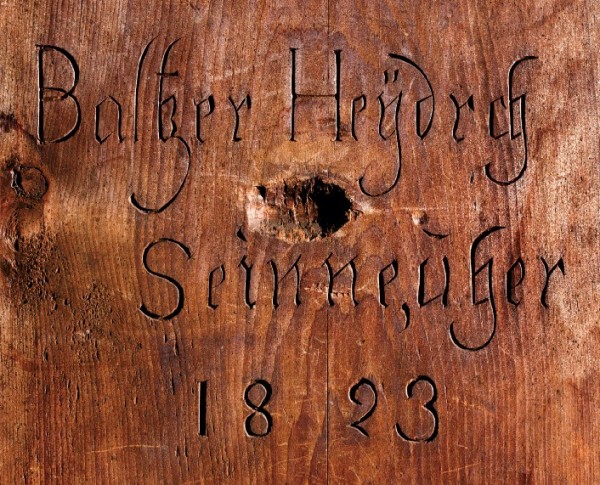

Detail of the inscription on the chest illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.) The “n” after Miller is a suffix applied to women’s surnames (both married and unmarried) in German; depending on the surname, an –n, –en/–in or –sen/–sin suffix was used (e.g., Hoffman/Hoffmanin).

House of George and Maria Catharina Miller, then Michael and Maria Elisabeth Miller, Millbach, Heidelberg Township, Lancaster County (now Millcreek Township, Lebanon County), Pennsylvania, built in 1752 and expanded by 1760. (Courtesy, Millbach Foundation, Inc.; photo, Laszlo Bodo.) The gable end of the original gambrel-roof house is to the right, and the addition built by Michael Miller, to the left.

Gristmill of Michael Miller, Millbach, Heidelberg Township, Lancaster County (now Millcreek Township, Lebanon County), Pennsylvania, built in 1784. (Courtesy, Millbach Foundation, Inc.; photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Date stone from the Miller house, 1752. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

Date stone of Michael Miller’s gristmill, 1784. (Courtesy, Millbach Foundation, Inc.; photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Staircase from the Miller house. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Pierre S. du Pont and Mr. and Mrs. Lammot du Pont, 1926.) The staircase was removed in 1926 along with other interior woodwork and installed as a period room at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Stove support from the Miller house, 1757. Stone. H. 14 3/4", W. 20 1/2", D. 5 1/2". (Courtesy of Conrad Weiser Homestead, Bureau of Historic Sites and Museums, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, CW74.190; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The foliate design above the initials is similar to one carved above the entry of the nearby Heinrich Zeller house, built in 1745 (see fig. 24).

Tall-case clock with movement by Jacob Graff (1729–1778), Lebanon, Lancaster (now Lebanon) County, Pennsylvania, 1750–1760. Walnut and mixed-wood inlays; brass, silvered brass, bronze, iron, steel; glass. H. 98", W. 24 1/4", D. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, bequest of Henry Francis du Pont, 1965.2261; photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Detail of the movement of the clock illustrated in fig. 10. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Chest, Millbach area, Heidelberg Township, Lancaster County (now Millcreek Township, Lebanon County), Pennsylvania, 1750–1775. Walnut with tulip poplar; iron. H. 25 1/2", W. 52 1/2", D. 26". (Courtesy, Millbach Foundation, Inc.; photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Hanging corner cupboard, Millbach area, Heidelberg Township, Lancaster County (now Millcreek Township, Lebanon County), Pennsylvania, 1750–1775. Tulip poplar; iron. H. 34", W. 37", D. 21". (Private collection; photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Winged angel head, Millbach area, Heidelberg Township, Lancaster County (now Millcreek Township, Lebanon County), Pennsylvania, 1750–1775. Unglazed earthenware. H. 5 3/4", W. 6 3/4", D. 2". (Courtesy, Millbach Foundation, Inc.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

New Year’s greeting for Michael and Maria Elisabeth Miller, attributed to Caspar Feeman Jr. (ca. 1725–1810), Millbach area, Heidelberg Township, Lancaster County (now Millcreek Township, Lebanon County), Pennsylvania, 1765. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 20 1/2" x 16 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, bequest of Henry Francis du Pont, 1957.1202; photo, Laszlo Bodo.) The foliate device framing the text is similar to that on the stove support illustrated in fig. 9.

Photograph of a birth and baptismal certificate for Johannes Miller (1766–1848), attributed to Caspar Feeman Jr. (ca. 1725–1810), Millbach area, Heidelberg Township, Lancaster County (now Millcreek Township, Lebanon County), Pennsylvania, ca. 1767. (Courtesy, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Frederick S. Weiser Collection.)

House of Valentine and Susanna Viehmann (Feeman), Millbach area, Heidelberg Township, Lancaster County (now Millcreek Township, Lebanon County), Pennsylvania, built in 1762. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

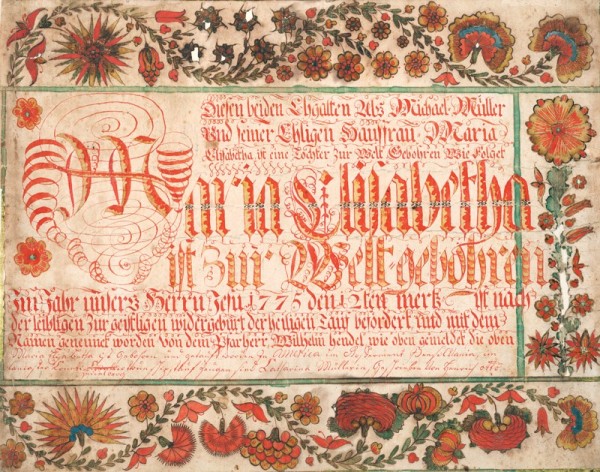

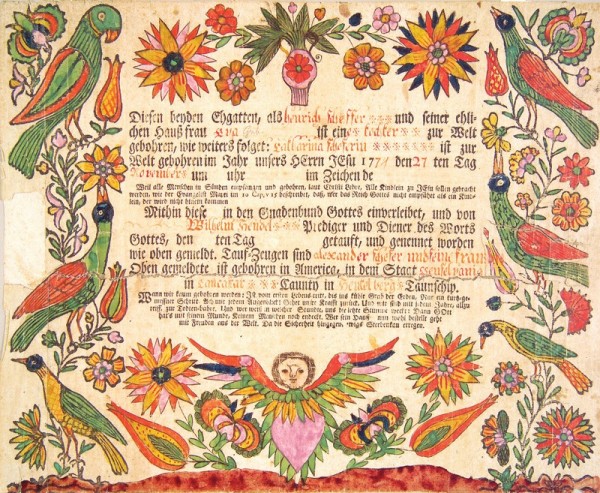

Birth and baptismal certificate for Maria Elisabeth Miller (1775–1843), by Henrich Otto (1733–ca. 1799), Millbach, Heidelberg Township, Lancaster County (now Millcreek Township, Lebanon County), Pennsylvania, ca. 1775. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 12 3/4" x 16 1/4". (Courtesy, Rare Book Department, Free Library of Philadelphia.)

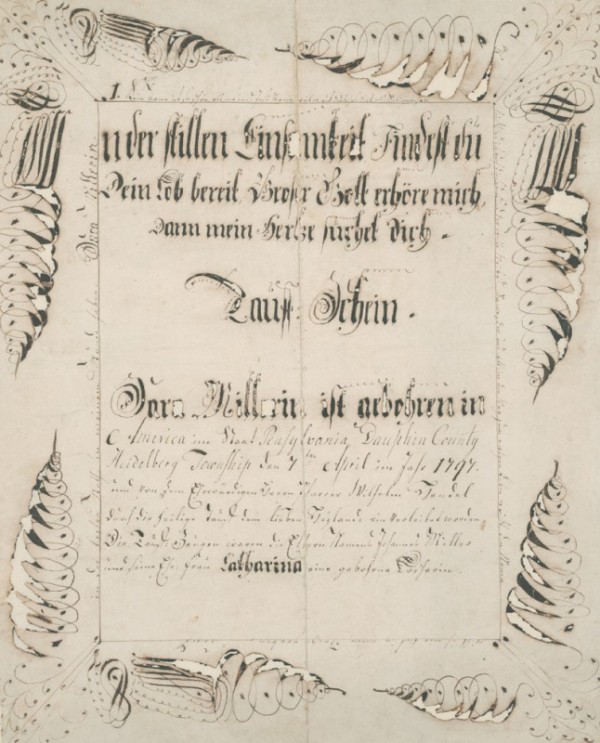

Birth and baptismal certificate for Sara Miller (1797–1870), Millbach, Heidelberg Township, Lancaster County (now Millcreek Township, Lebanon County), Pennsylvania, ca. 1797. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 15 3/4" x 12 3/4". (Courtesy, Rare Book Department, Free Library of Philadelphia.)

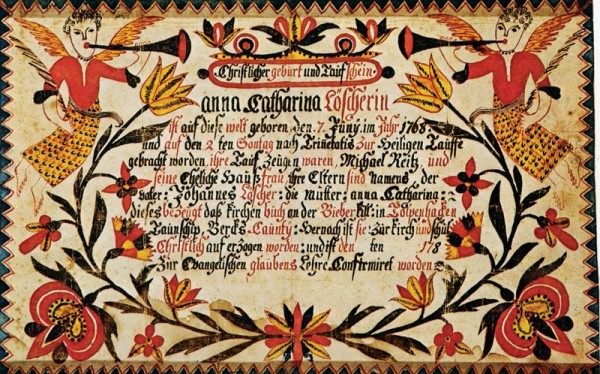

Birth and baptismal certificate for Anna Catharina Lescher (1768–1808), attributed to Johann Conrad Gilbert (1734–1812), ca. 1785. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 8 1/4" x 12 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail of the line-and-berry inlay on a drop-leaf table owned by James and Elizabeth Bartram, possibly by James Bartram (1701–1771), Marple Township area, Chester (now Delaware) County, Pennsylvania, 1725. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, promised gift of Mr. and Mrs. John L. McGraw; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Map of southeastern Pennsylvania showing the location of the Tulpehocken Valley and the counties of Berks, Dauphin, Lancaster, and Lebanon. (Artwork, Nichole Drgan.)

House of Heinrich Zeller, near Newmanstown, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, built in 1745. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.) The central chimney and flared kick to the roof are Germanic features.

Detail of the door lintel of the Zeller house. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.) The foliate device framing the shield is similar to that on the stove support illustrated in fig. 9.

Charming Forge Mansion, built for George Ege, near Womelsdorf, Heidelberg Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1783. (Photo, Kurfiss/Sotheby’s International Realty.)

Christ Lutheran Church, near Stouchsburg, Marion Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania, built in 1786. (Courtesy, Mr. and Mrs. Michael Emery.)

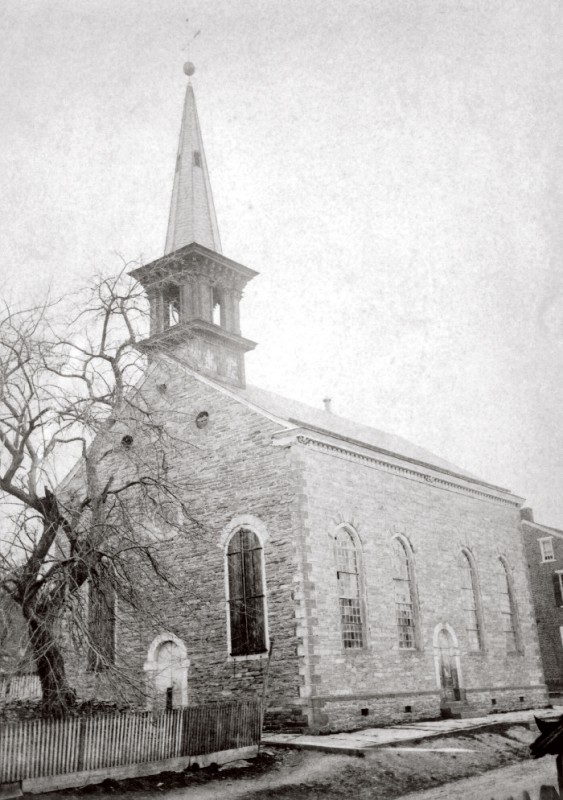

St. Luke Lutheran Church, Schaefferstown, Heidelberg Township, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, built between 1765 and 1767. (Courtesy, Historic Schaefferstown, Inc.) This photograph was taken before 1884, when the church was remodeled.

Winged angel heads from St. Luke Lutheran Church, Schaefferstown, Heidelberg Township, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1767. Pine. H. 36", W. 22", D. 6" (framed). (Courtesy, Katharine and Robert Booth; photo, Laszlo Bodo.) The frame is modern.

Chest, Elizabeth Township area, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1790. Walnut and mixed-wood inlay (including sumac, maple, holly, and fruitwood) with white pine; iron, brass. H. 30 1/4", W. 55 3/4", D. 24 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The lower section, including the drawers, base molding, and feet, is rebuilt.

Detail of the inscription on the chest illustrated in fig. 29. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall-case clock, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1790. Walnut and mixed-wood inlay (including sumac) with white pine; brass, painted sheet iron, iron, bronze, steel; glass. H. 93 1/2", W. 22 1/4", D. 12 1/8". (Courtesy, John J. Snyder Jr.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet are replaced.

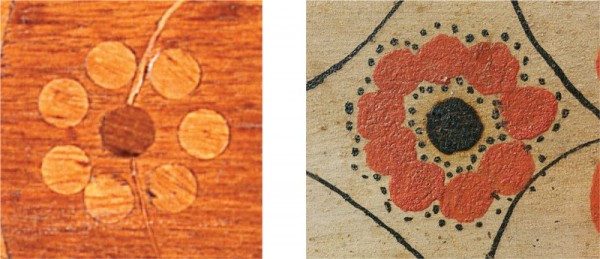

Detail of the inlay on the chest illustrated in fig. 29 (right) and the clock illustrated in fig. 30 (left). (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall-case clock with movement by Jacob Diehl (d. 1857), Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1790. Walnut and mixed-wood inlay with pine; brass, painted sheet iron, iron, bronze, steel; glass. H. 96 1/2", W. 21 1/2", D. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchase, Douglas and Priscilla deForest Williams, Mr. and Mrs. Eric M. Wunsch, and The Sack Foundation Gifts, 1976.279; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the clock illustrated in fig. 33. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

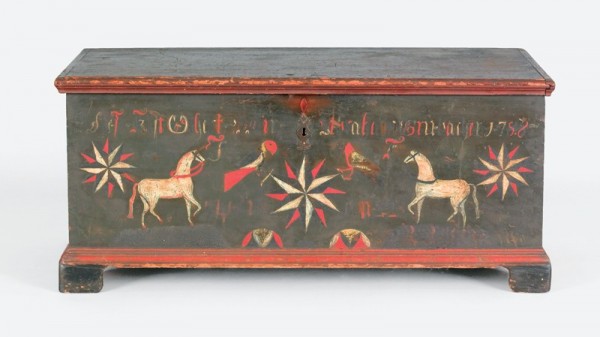

Chest, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1788. White pine; iron, brass. H. 26 3/4", W. 54", D. 2 1/2@". (Private collection; photo, David Bohl.) The feet are replaced.

Detail of the till lid inside the chest illustrated in fig. 48. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a crayon mark inside the chest illustrated in fig. 57. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Carrying handles on the chests illustrated in figs. 29 (above) and 48 (below). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the lock inside the chest illustrated in fig. 48. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details of the lock inside the chest illustrated in fig. 52. This lock is similar to the examples shown in fig. 86.

Detail of pomegranate motifs on the chests illustrated in figs. 1, 48, 52, and 55.

Detail of flower motifs on the chests illustrated in figs. 1 and 52.

Detail of the inscription on the chest illustrated in fig. 48. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the small drawers under the till of the chest illustrated in fig. 76. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the decoration and inscription on the chest illustrated in fig. 35. (Photo, David Bohl.)

Box, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1828. (Courtesy, James and Nancy Glazer.)

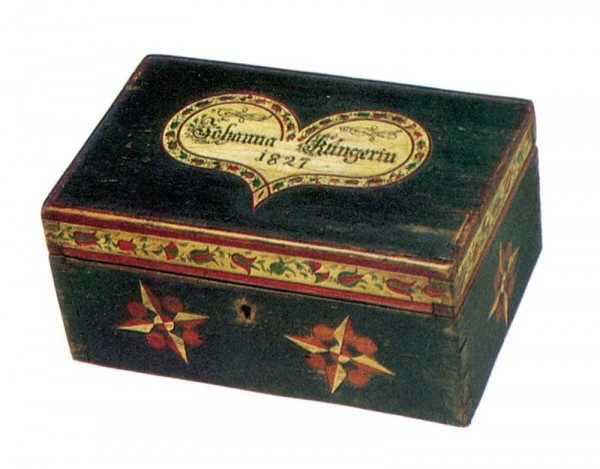

Box, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1827. (Private collection; photo, Schecter Lee.)

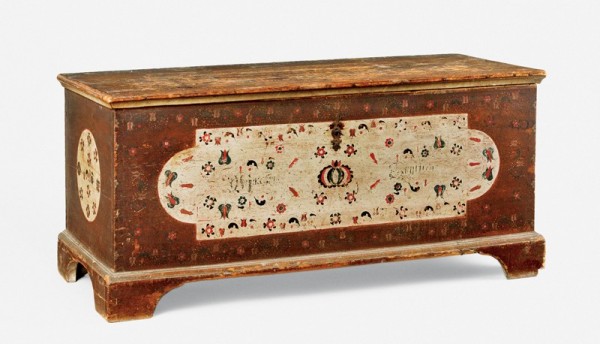

Chest, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1789. Tulip poplar; iron. H. 23 1/2", W. 53 3/4", D. 23". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a hinge inside the chest illustrated in fig. 48. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1790. Pine and tulip poplar; iron. H. 25", W. 54", D. 23 1/2". (Courtesy, Detroit Institute of Arts, USA/The Bridgeman Art Library, 41.127). The feet are replaced.

Chest, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1793. Materials and dimensions unrecorded. (Photo, Clarence Spohn.)

Chest, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1790. Tulip poplar and pine; iron, brass. H. 26 3/4", W. 52", D. 23 1/8". (Courtesy, a Museum of Fine Arts, Boston trustee and her spouse; photo, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

Detail of the lid of the chest illustrated in fig. 52.

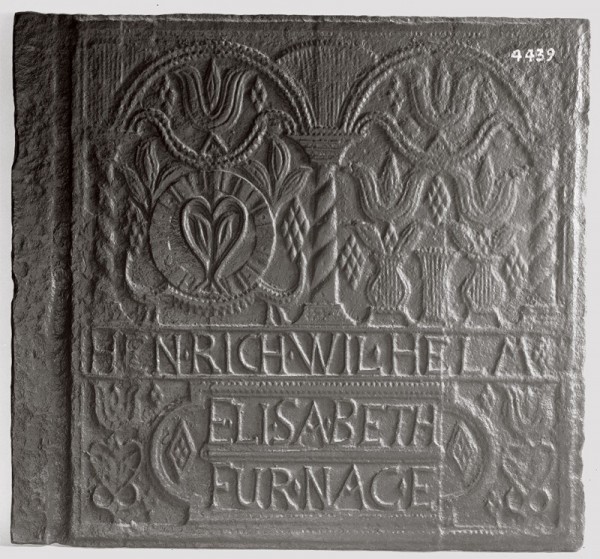

Stove plate, Elisabeth Furnace, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Iron. 23 1/2" x 25 1/2". (Courtesy, Mercer Museum of the Bucks County Historical Society.)

Chest, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1795. White pine; iron, brass. H. 22 3/4", W. 50", D. 21 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet are replaced.

Chest, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1796. Tulip poplar; iron. H. 23 3/4", W. 51 1/2", D. 22 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet are replaced.

Chest, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1790. White pine; iron. H. 23 1/2", W. 52", D. 22 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the underside of the till of the chest illustrated in fig. 57. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the end panel of the chest illustrated in fig. 57. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1790. White pine and tulip poplar; iron. H. 23 1/2", W. 51 5/8", D. 22 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet are replaced.

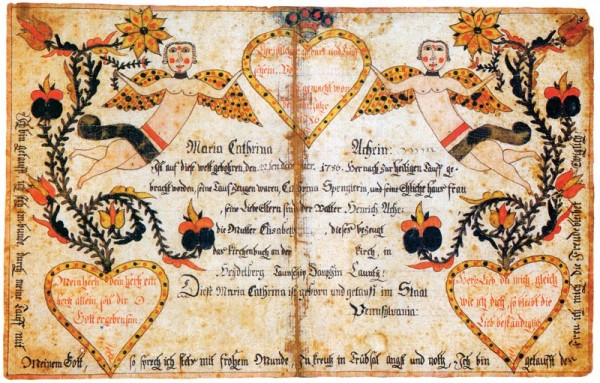

Birth and baptismal certificate for Maria Catharina Ache, attributed to Johann Henrich Goettel (1745–1807), Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1786. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 7 3/4" x 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

Chest, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1790. White pine and tulip poplar; iron. H. 22", W. 50", D. 21 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Raymond Martinot.)

Zither, attributed to Samuel Ache (1764–1832), Schaefferstown, Heidelberg Township, Dauphin (now Lebanon) County, Pennsylvania, 1788. Maple and pine; iron. H. 1 7/8", W. 3 3/4", L. 37 3/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, gift of Mrs. Jeannette S. Hamner, 2000.708.1.) The inscription on the side reads “Das Hertze mein, Soll dir Allein, Ergeben sein, Amen das werde Wahr, wir wollen Singen und Spihlen Ein gantzes jahr / Heydelberg Daunschip Dauphin Caunty 27 Den feberwari SAMUEL ACHE 1788” (This heart of mine shall be given to you alone, Amen. That is true we will sing and play an entire year. Heidelberg Township, Dauphin County 27th of February Samuel Ache 1788).

Detail of the inscription on the zither illustrated in fig. 63.

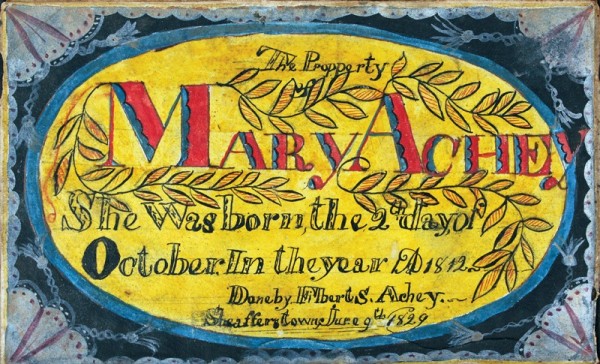

Bookplate for Mary Ache, by Filbert Achey (1812–1832), Schaefferstown, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, 1829. Watercolor and ink on wove paper. 3 1/4" x 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Dr. and Mrs. Robert M. Kline; photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

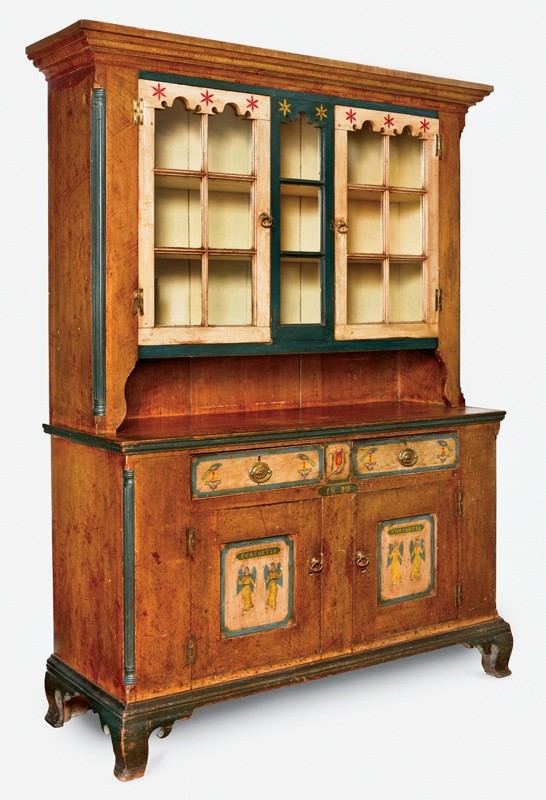

Schrank, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1790. Pine; iron, brass. H. 80", W. 70", D. 21". (Courtesy, Pook & Pook.)

Detail of the tulips on the zither illustrated in fig. 63.

Chest, probably by Moses Pyle (d. 1784), London Grove Township area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, 1747. Walnut and mixed-wood inlay (including sumac, maple, and holly) with white oak, white cedar, and tulip poplar; brass, iron. H. 14 1/4", W. 21 1/8", D. 13 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, partial purchase and partial gift of William R. Smith and sons in memory of Marjorie B. Smith, wife and mother, 2001.19; photo, Laszlo Bodo.) The left drawer is replaced.

Chest façade, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1790. White pine; iron. 14 1/2" x 50 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The façade retains its original lock (fig. 86).

Chest, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1805. Pine; iron. H. 23 1/2", W. 52 1/2", D. 23". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet are replaced.

Details showing the painted faces on the chest illustrated in fig. 70 and a fraktur. (Private collection.)

Chest, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1790. Pine; iron, brass. H. 29 1/2", W. 53 1/2", D. 23". (Courtesy, Christie’s.) The feet are replaced.

Pair of date boards on the house of Johannes and Anna Maria Bollman and their son George Bollman, Millbach, Heidelberg (now Millcreek) Township, Lebanon County, 1819. (Photo, Laszlo Bodo.) The paint is restored, based on evidence found under a layer of white overpaint.

Chest, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1792. Tulip poplar; iron. H. 19 1/2", W. 45 1/2", D. 23". (Courtesy, Renfrew Museum and Park, Waynesboro, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the end of the chest illustrated in fig. 74. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1794. Tulip poplar; iron. H. 24", W. 50", D. 22 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

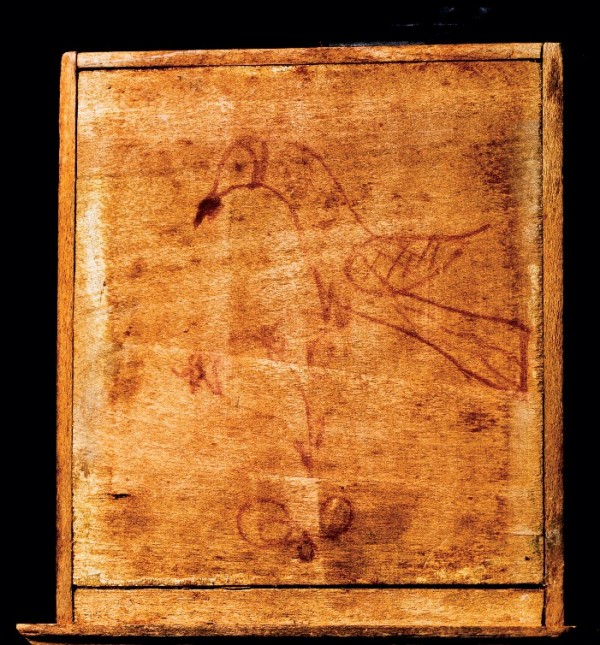

Detail of the bird drawing on the underside of the till drawer of the chest illustrated in fig. 76. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

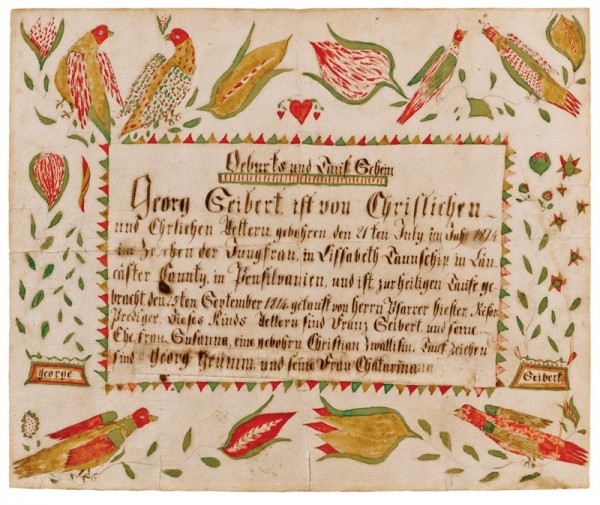

Birth and baptismal certificate for George Seibert, attributed to Andreas Kessler, Elizabeth Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1815. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 12 5/8" x 15 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1795. Tulip poplar and pine; iron. H. 23", W. 50", D. 23". (Courtesy, Peter Tillou; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1795. Tulip poplar and pine; iron, brass. H. 26 3/4", W. 51 1/2", D. 23 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Milly McGehee.)

Chest, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1798. Tulip poplar; iron. H. 24 5/8", W. 51 1/2", D. 23". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Berks County Museum and Library, Reading, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1792. Tulip poplar and pine; iron, brass. H. 21 7/8", W. 51 1/2", D. 23". (Courtesy, Milwaukee Art Museum, Layton Art Collection, L2000.1; photo, Larry Sanders.)

Chest, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1793. White pine and tulip poplar; iron. H. 22 1/4", W. 51 1/4", D. 21 3/4". (Courtesy, Greg K. Kramer Antiques; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, Heidelberg Township area, Lebanon or Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1797. White pine; iron. H. 22", W. 50 1/2", D. 21 3/4". (Courtesy, Olde Hope Antiques; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the decoration and inscription on the chest illustrated in fig. 84. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details showing the tops and inner surfaces of three locks, the center example installed on the chest illustrated in fig. 69, probably by Henry Seiler (d. 1785) or Henry Seiler Jr. (b. 1772), Lebanon, Lebanon County, ca. 1780–1790. (Courtesy, Sidney Gecker and Philip H. Bradley Co.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

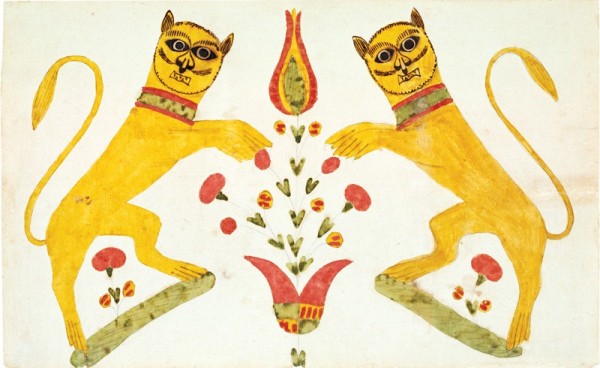

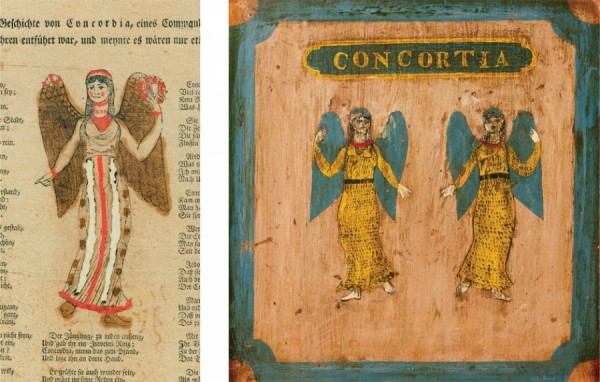

Drawing, attributed to Henrich Otto (1733–ca. 1799), probably Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1775–1785. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 7 3/4" x 12 5/8". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of George H. Lorimer, 25-95-2.)

Chest, probably Alsace or Windsor Township area, Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1788. Tulip poplar; iron, brass. H. 28 3/8", W. 50", D. 24". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, bequest of Henry Francis du Pont, 1959.2804.) The feet are replaced.

Chest, probably Rapho Township area, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1782. Tulip poplar and pine; iron. H. 23", W. 53 1/2", D. 21 5/8". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of George H. Lorimer, 25-95-1; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet are replaced.

Chest, probably Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1803. Tulip poplar and pine; iron, brass. H. 27", W. 50", D. 22". (Private collection; photo, Pook & Pook.)

Chest, probably by John Flory (1767–1836), Rapho Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1791. Tulip poplar and pine; iron. H. 25", W. 50", D. 24". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Titus C. Geesey Collection, 58-110-1; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

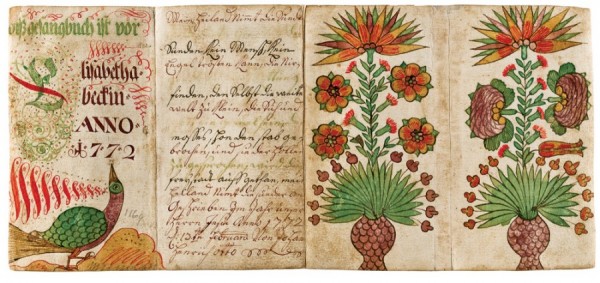

Bookplate for Elisabetha Beck, by Henrich Otto (1733–ca. 1799), probably Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1772. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 6 1/8" x 13 1/2". (Courtesy, Schwenkfelder Library & Heritage Center, Pennsburg, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The tapering spiral motif after Otto’s signature, which he often used for embellishment or to fill space, is related to similar designs used to mark the inside of some chests (see fig. 37).

Birth and baptismal certificate for Johannes Schaeffer, by Henrich Otto (1733–ca. 1799), Schaefferstown, Heidelberg Township, Lancaster (now Lebanon) County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1782. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 12 5/8" x 15 3/4". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. Robert W. de Forest, 1933, 34.100.66; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details of the pomegranate motifs on the chest illustrated in fig. 48 and the fraktur illustrated in fig. 18.

Chest, painted decoration attributed to Henrich Otto (1733–ca. 1799), Earl Township area, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1780. Tulip poplar with oak and walnut; iron. H. 23", W. 50 1/2", D. 21 1/4". (Courtesy, State Museum of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 73.163.83; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the floral motifs on the chest illustrated in fig. 95. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, painted decoration attributed to Henrich Otto (1733–ca. 1799), Millbach area, Heidelberg Township, Lancaster County (now Millcreek Township, Lebanon County), Pennsylvania, 1783. Tulip poplar; iron. H. 23 1/8", W. 49 3/4", D. 22 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet are replaced.

Detail of the lid on the chest illustrated in fig. 97. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, painted decoration probably by Henrich Otto (1733–ca. 1799), Earl Township area, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1772. Tulip poplar; iron. H. 24 5/8", W. 52 1/8", D. 22 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

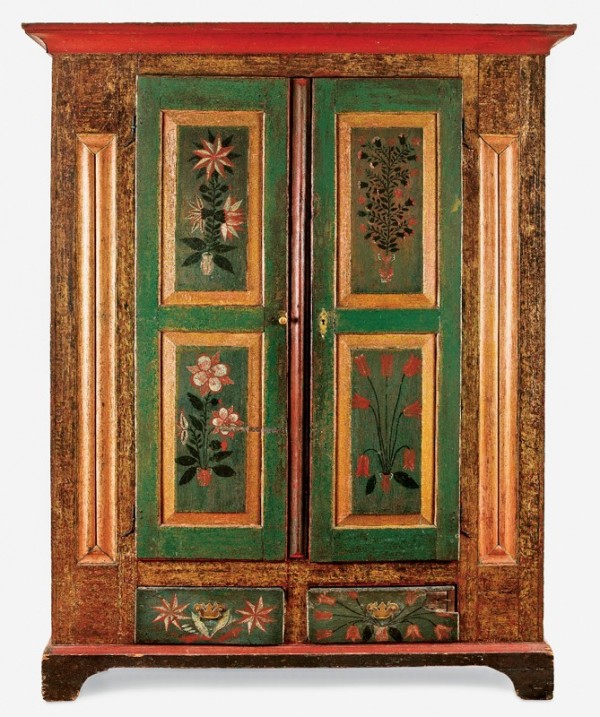

Schrank, painted decoration probably by Henrich Otto (1733–ca. 1799), probably Earl Township area, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1775. Tulip poplar; iron, brass. H. 82", W. 64", D. 19". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

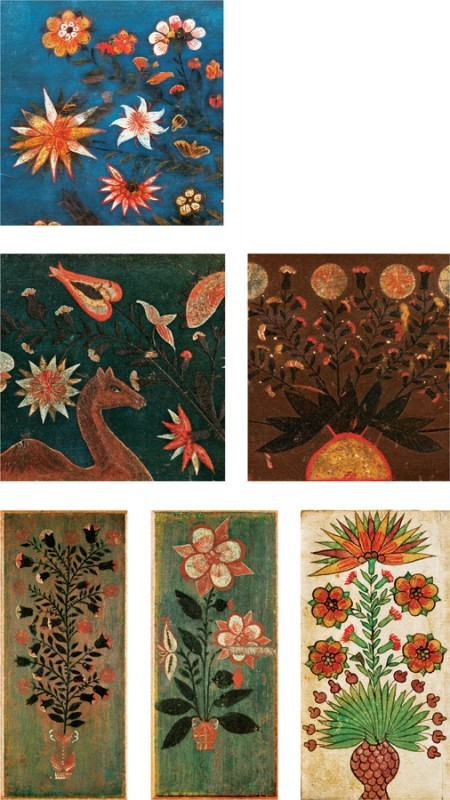

Details showing the flowers on the chests illustrated in figs. 95, 97, 99; schrank in fig. 100; and fraktur in figs. 92 and 93.

Details showing flowers on the fraktur illustrated in fig. 93 and the chest illustrated in fig. 95.

Details showing the letters and dates on the fraktur illustrated in fig. 92 and the chests illustrated in figs. 95 and 97.

Birth and baptismal certificate for Johann Michael Moor (b. 1776) by Friedrich Speyer (act. ca. 1774–1801), Millbach, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, 1784. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 13" x 16". (Private collection; photo, Irwin Richman.) The certificate is signed by Speyer and inscribed “Schulmeister au der Mühlbach” (Schoolmaster on the Mill Creek).

Birth and baptismal certificate for William Heiser (b. 1843), infill by Conrad Otto (ca. 1770–1857) on a form printed by Gustav S. Peters in Harrisburg, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1840. Watercolor and ink on wove paper. 16 1/2" x 12 7/8". (Courtesy, Philip and Muriel Berman Museum of Art at Ursinus College, Pennsylvania Folklife Society Collection, PAG1998.218; photo, Glenn Holcombe.)

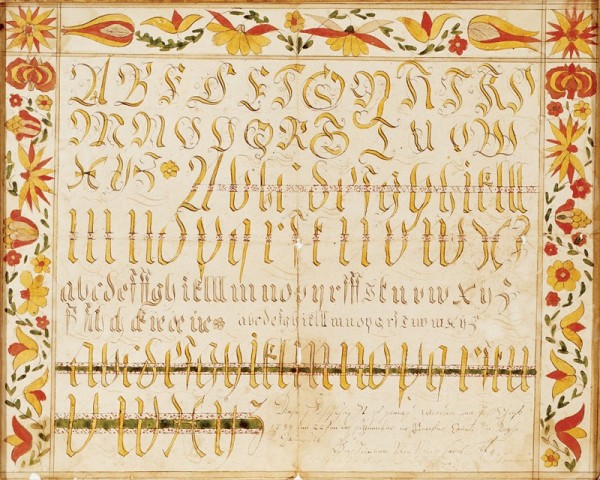

Writing sample, by Jacob Otto (ca. 1762–ca. 1825), Rapho Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1795. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 16 3/4" x 21". (Private collection; photo, Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Frederick S. Weiser Collection.)

Birth and baptismal certificate for Maria Breneise (b. 1770), infill and decoration by Jacob Otto (ca. 1762–ca. 1825) on a form printed at Ephrata, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1784. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 13 3/8" x 16 5/8". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of J. Stogdell Stokes, 28-10-91.)

Birth and baptismal certificate for Catharina Schaeffer (b. 1774), infill and decoration attributed to Jacob Otto (ca. 1762–ca. 1825) on a form printed at Ephrata, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1787. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 12 1/2" x 15 3/4". (Courtesy, Philip and Muriel Berman Museum of Art at Ursinus College, Pennsylvania Folklife Society Collection, pag1998.156.) The vase with cluster of leaves is similar to that on the chest illustrated in fig. 95. Although the flowers on this fraktur are quite similar to those on examples signed by Henrich Otto, there is a slightly heavier feel to them, suggesting that Jacob Otto both infilled and embellished this work.

Chest, probably by John Flory (1767–1836), Rapho Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1799. Pine; iron. H. 26", W. 52 1/4", D. 24". (Private collection; photo, Christie’s Images/Bridgeman Art Library.)

Chest, probably by John Flory (1767–1836), Rapho Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1788. Pine; iron. H. 21 1/2", W. 50", D. 21 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Pook & Pook.)

Chest, probably by John Flory (1767–1836), Rapho Township area, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1792. White pine; iron. H. 24 1/2", W. 50", D. 23". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the chest illustrated in fig. 111. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, probably by John Flory (1767–1836), Rapho Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1794. Pine; iron. H. 26 1/4", W. 50", D. 23". (Courtesy, American Museum in Britain, Bath, UK.)

Chest, probably by John Flory (1767–1836), Rapho Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1794. Pine; iron. H. 22 1/2", W. 51 3/4", D. 22". (Private collection; photo, courtesy of Christie’s Images/Bridgeman Art Library.)

Chest, possibly by Jacob Otto (ca. 1762–ca. 1825), Rapho Township area, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1791. Walnut with pine and walnut; brass, iron. H. 27 5/8", W. 56", D. 26". (Courtesy, G. W. Samaha; photo, Rob Manko.)

Birth and baptismal certificate for Anna Maria Haberack, by William Otto (1761–1841), Lower Mahantongo Township, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, 1834. Watercolor and ink on wove paper. 12" x 15 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, attributed to William Otto (1761–1841), Lower Mahantongo Township, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, 1812. Pine; iron, brass. H. 23 1/4", W. 52 3/4", D. 18 1/4". (Courtesy, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.)

Chest, attributed to William Otto (1761–1841), Lower Mahantongo Township, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, 1814. Tulip poplar and white pine; iron. H. 22 5/8", W. 51", D. 22 1/2". (Courtesy, Olde Hope Antiques; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the chest illustrated in fig. 118. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

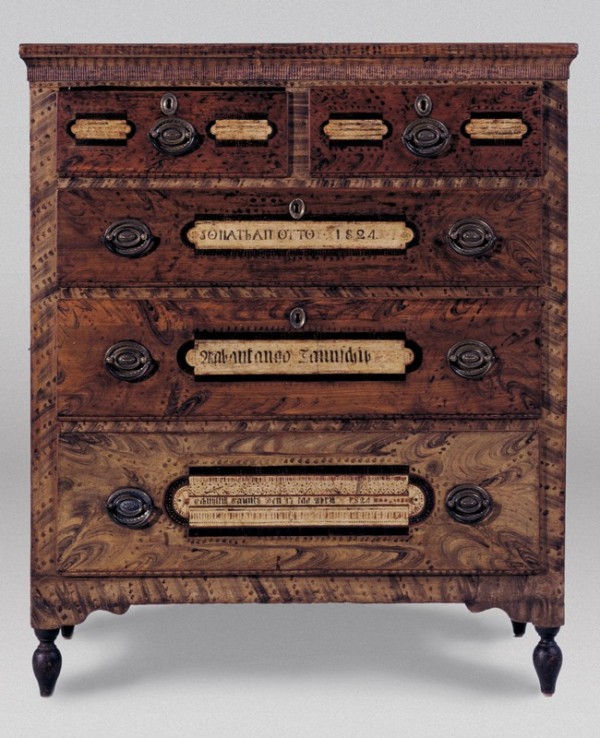

Chest of drawers, attributed to William Otto (1761–1841), Lower Mahantongo Township, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, 1824. Pine; brass. H. 44", W. 40", D. 19". (Private collection; photo, Olde Hope Antiques.) The feet are replaced.

Birth and baptismal certificate for Christian Zimmerman (b. 1799), attributed to Daniel Otto (ca. 1770–ca. 1820), probably Centre County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1815. Watercolor and ink on laid paper 7 1/2" x 12 1/2". (Courtesy, a trustee of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and her spouse; photo, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

Drawing, attributed to Daniel Otto (ca. 1770–ca. 1820), probably Centre County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1815. Watercolor, pencil, and ink on laid paper. 8 1/8" x 13 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1959.305.2.)

Drawing, attributed to Henrich Otto (1733–ca. 1799), probably Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1780. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 13 1/8" x 16 1/2". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, 1966.66.242.1; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, painted decoration probably by Daniel Otto (ca. 1770–ca. 1820), probably Centre County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1815. White pine and tulip poplar; iron. H. 27", W. 50", D. 21". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, probably Centre County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1815. White pine; iron, brass. H. 27 1/2", W. 50 3/4", D. 21 7/8". (Courtesy, Barnes Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, probably Lancaster or Centre County, Pennsylvania, 1790–1815. Tulip poplar; iron. H. 23 1/2", W. 48", D. 20 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet are replaced.

Details showing the lions on the chests illustrated in figs. 124–26. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest, painted decoration probably by Daniel Otto (ca. 1770–ca. 1820), probably Centre County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1815. Pine; iron. H. 24 3/4", W. 48", D. 23". (Private collection; photo, Sotheby’s.)

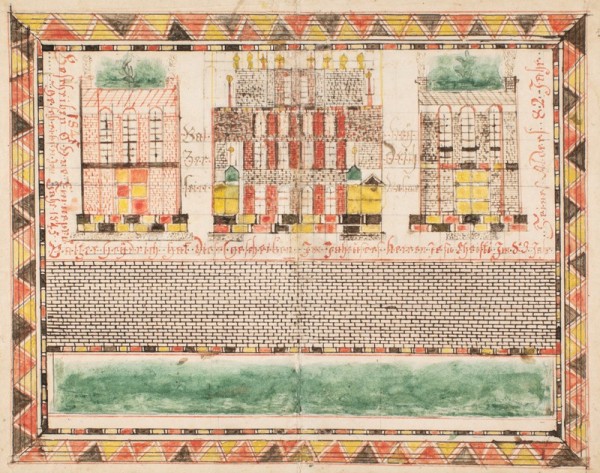

Tall-case clock with case by Baltzer Heydrich (1765–1846) and movement by Abraham Swartz, Lower Salford Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, 1823. Cherry with mixed-wood inlays; brass, painted sheet iron, iron, bronze, steel; glass. H. 90 1/2", W. 21 7/8", D. 11 1/4". (Courtesy, Schwenkfelder Library and Heritage Center, Pennsburg, Pa. gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Calhoun; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Inside the pendulum door the date “October 18th 1823” is written in chalk.

Detail of the inscription inside the clock illustrated in fig. 129. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Drawing, by Baltzer Heydrich (1765–1846), Lower Salford Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, 1845. Watercolor and ink on wove paper. 12 7/8" x 16 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, 1959.141; photo, Jim Schneck.)

Chest with printed broadside decorated by Friedrich Speyer (act. ca. 1774–1801), Probably Bern Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1790. White pine; iron, brass. H. 28", W. 50 5/8", D. 22 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, 1955.95.1; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall-case clock with movement by Heinrich Rentzheimer, Salisbury Township, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1788. Walnut with pine; watercolor and ink on laid paper; brass, painted sheet iron, iron, bronze, steel; glass. H. 99", W. 23 3/4", D. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, James and Nancy Glazer.) The bottom third of the lower section and the feet are rebuilt.

Detail of the fraktur in the waist door of the clock illustrated in fig. 133.

Chest of drawers, Mahantongo Valley, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1835. Tulip poplar and yellow pine; brass. H. 52 1/2", W. 44", D. 20". (Courtesy, Katharine and Robert Booth; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details showing an angel on a fraktur printed by Henrich Ebner, Allentown, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1820 and the chest illustrated in fig. 135. (Courtesy, Katharine and Robert Booth; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Kitchen cupboard, Mahantongo Valley, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, 1830. Tulip poplar and pine; glass; brass. H. 83 1/4", W. 66", D. 33 1/2". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Titus C. Geesey Collection, 54-85-32a,b; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details showing the angel on the broadside of the poem Concordia printed by Daniel P. Lange and the angels on the door of the cupboard illustrated in fig. 137, Hanover, Adams County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1825. (Courtesy, York County Heritage Trust.) Printer John S. Wiestling of Harrisburg, Dauphin County, also used similar angels.

Chest, Mahantongo Valley, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1835. Yellow pine and tulip poplar; iron, brass. H. 28 1/2", W. 49 7/8", D. 21". (Courtesy, Katharine and Robert Booth; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The drawers are false.

Details of a praying child on the chest illustrated in fig. 139 and a praying child from a birth and baptismal certificate with printing attributed to Jacob Schnee, Lebanon, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1815. (Courtesy, Rare Book Department, Free Library of Philadelphia.)

Chest, Mahantongo Valley, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, 1831. Yellow pine and tulip poplar; iron, brass. H. 29 7/8", W. 50", D. 23". (Courtesy, Katharine and Robert Booth; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet are replaced.

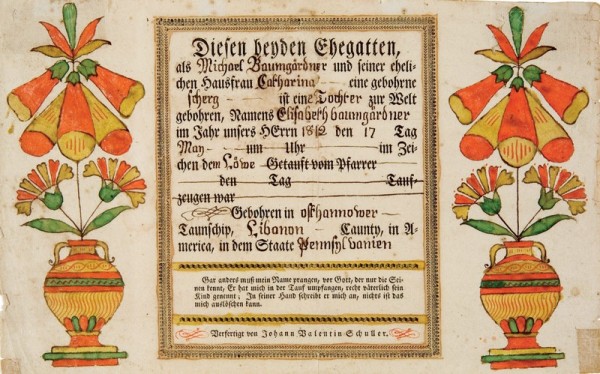

Birth and baptismal certificate for Elisabeth Baumgardner (b. 1812), by Johann Valentin Schuller Jr. (1759–ca. 1816), on a form probably printed in Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1811. Watercolor and ink on laid paper. 7 1/2" x 12 3/8". (Courtesy, Philip and Muriel Berman Museum of Art at Ursinus College, Pennsylvania Folklife Society Collection, PAG1998.173.)

Chest, probably Mahantongo Valley, Northumberland County or Centre County, Pennsylvania, 1800–1820. Pine; iron, brass. H. 24 3/4", W. 50", D. 17 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, 1957.99.4).

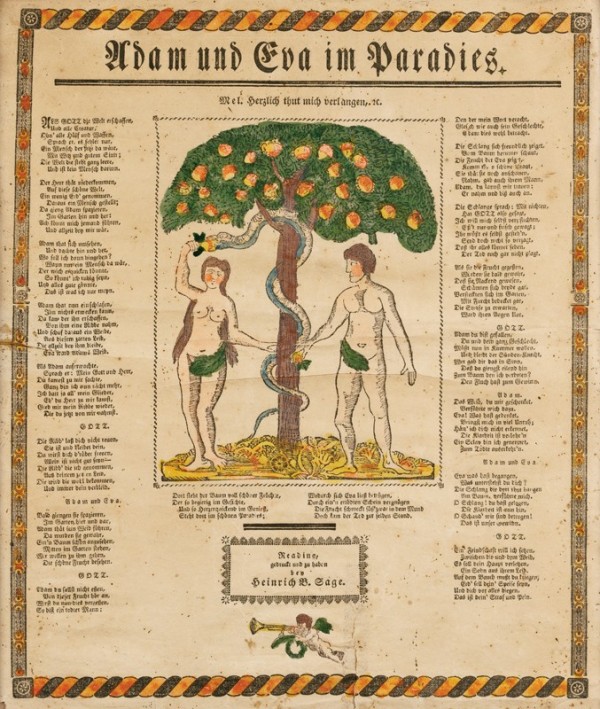

Broadside of Adam and Eve, printed by Heinrich B. Sage, Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1820. Watercolor and ink on wove paper. 14 1/2" x 12 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

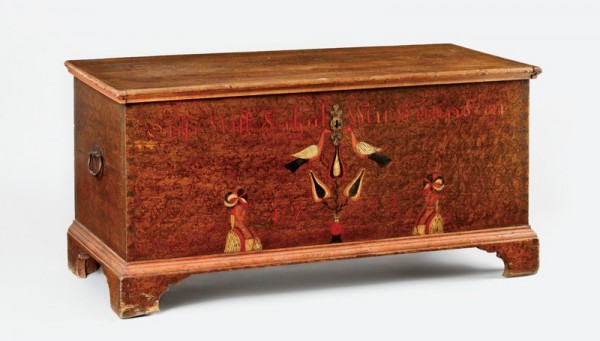

In 1792 an extraordinary walnut chest with inlaid decoration was made for Maria Elisabeth Miller (fig. 1). Many unusual features distinguish this object, most notably the four external drawers within the main compartment and three lower drawers, two interior tills, and one till drawer (fig. 2). This extravagant construction would have added greatly to the overall cost of the chest, requiring additional labor to build the seven exterior drawers as well the cost of brass locks, escutcheons, and pulls for each. Walnut was also a more expensive choice than tulip poplar or pine, as were the ogee feet, which are more difficult to make than straight bracket or turned feet. Although the exact cost of the Miller chest is unknown, some idea can be derived from the account book of Bucks County joiner Abraham Overholt, who charged £1.10 in 1792 for a pine chest with three drawers, painted brown, and £3 in 1799 for a “walnut chest with three drawers, locks and hardware.” The Miller chest has inlaid floral motifs on a large horizontal panel that is attached to a mortise-and-tenoned frame, rather than the more typical single-board façade. Presumably the maker used that construction to accommodate the external drawers flanking the panel. A second panel containing the owner’s name, in elaborate German Fraktur lettering, is inset within the larger panel (fig. 3). Who was Maria Elisabeth Miller? Why was her chest built and inlaid in such a singular and costly manner, and who made it? Was the elaborate lettering of Maria Elisabeth’s name rendered by the maker of the chest or by a professional calligrapher such as a fraktur artist? Although not all of these questions can be definitively answered, the examination of the Miller chest and other related inlaid or painted objects sheds light on the remarkable furniture production of a distinctive cultural region and enables an exploration of the myriad connections between fraktur and furniture.[1]

The Miller Chest

The identification of Maria Elisabeth Miller is critical for understanding this chest within its original context and exploring its relation to other objects. Maria Elisabeth Miller (1775–1843) was the youngest child of Michael and Maria Elisabeth (Becker) Miller of Millbach, in Heidelberg Township, Lancaster County (now Millcreek Township, Lebanon County). Named after the Mill Creek or Mühlbach, the village was home to several families who attained significant wealth through farming and milling. Four miles to the southwest was Schaefferstown, the largest settlement in the area (see fig. 22). In 1746 Maria Elisabeth’s paternal grandfather, George Miller, provided an acre of land on which a German Reformed church and schoolhouse were built. Construction of the church began in 1751, and in 1770 Lutheran patriarch Henry Melchior Muhlenberg (1711–1787) described it as “built of massive stones and is furnished with a tower. . . . Lying between trees and open fields, it offers a pleasant prospect.”[2]

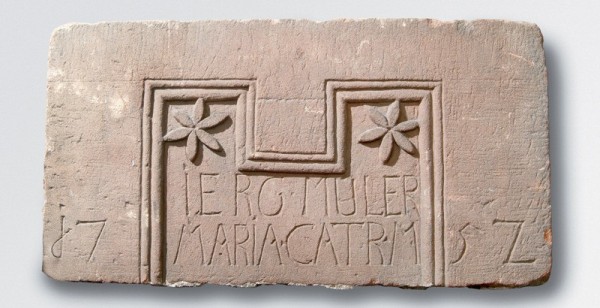

A German immigrant, George Miller (1706–1791) and his wife, Maria Catharina Stump (1711–1787), built a large stone house along the banks of the Mill Creek in 1752 (fig. 4). The house was soon expanded by their son Michael (1732–1815), who subsequently built a new gristmill that was attached to the main house and likely replaced an older mill in the same location (fig. 5). This house-mill combination is particularly associated with the Pennsylvania Germans and is a rare survival of a European house type. Notable is the house’s kicked gambrel roof, which provided a large attic well suited for the storage of grain. Two carved date stones (figs. 6, 7) were made for the buildings, one for the house with the inscription “JERG MULER / 17 MARIA CATR M 52” and the other for the mill, “1784 / GOTT ALEIN DE EHR (God alone the Honor) / MICHAEL MIELER / M ELISABET MILERN.” The interior of the house is equally impressive, with a Germanic floor plan consisting of a large kitchen, stove room, and bedchamber on the first floor. Other distinctive features include elaborately paneled doors and a massive staircase with square-sawn balusters in the German baroque manner (fig. 8).[3]

In 1753 George Miller transferred the house, mill, and 144 acres to his son Michael. According to the deed, George was then a resident of Rowan County, North Carolina. Records there appear to confirm the family tradition that George left his wife, Maria Catharina, behind in Pennsylvania and moved to North Carolina with a servant girl. In 1754 he applied for a license to keep a tavern on his plantation in Rowan County. Deed books show that George settled on Abbotts Creek, now part of Davidson County, and established a gristmill. In 1773 he transferred three enslaved servants “for natural love & affection to & for services of 20 yrs. to Glory Miller otherwise Glory Lettsler.” In his will of 1785, George refers to his wife, “Glory Litsler Miller,” as well as four sons, John, Jacob, David, and Frederick. He died in 1791. On the heels of this family scandal, Michael Miller acquired the Millbach property at only twenty-one years of age. He would become one of the wealthiest men in the community by the time of his death in 1815 and was consistently taxed at one of the highest rates of all residents in Heidelberg Township. In addition to expanding the house (probably to provide his mother with independent living quarters) and building a new gristmill, Michael made other improvements, including the construction of a sawmill by 1777. When the federal direct tax was taken in 1798, Heidelberg Township had a total of nine saw- or gristmills, two of which were owned by Michael Miller. His property comprised the large stone house; a two-storey stone gristmill of 50 by 20 feet, with two pairs of stones and described as “in good order, new”; a sawmill of 40 by 12 feet with double gears, “in very good order”; a large barn of 100 by 28 feet; and a log still house of 30 by 20 feet in “good order.” The house and mill were assessed at $1,000.00 each; by comparison, the average tradesman’s house in Schaefferstown was valued at $268 and the average farmhouse at $434.00.[4]

A partial inventory conducted after Michael Miller’s death in 1815 lists a table, stove and pipes; a bed and bedstead worth £3.15 and three more bedsteads; “1 Closset” (likely a schrank) worth £4.10; a “spinet” worth £11.5; “1 Conk shell”; a chest, cradle, dough trough, and meal chest; two kitchen dressers; four tables; a corner cupboard; and extensive pewter including a dozen plates, seventeen spoons, seven basins, and five other “large” forms. Also appraised were a still kettle valued at £16.17.6 and “63 vesels the half belonging to the Stillery” valued at £22.10.6. Known furnishings of the Miller house are as Germanic as the architecture. The stove room was heated by a large iron stove, fed through the back of the kitchen hearth, which was supported by an ornately carved stone (fig. 9) inscribed with the date “1757” and initials “MM / MLM” (for Michael Miller and Maria [E]lisabeth Miller), along with symbols of the miller’s trade—lower half of the main wooden gear from a gristmill, a square, and dividers. A tall-case clock (fig. 10) with eight-day movement by Jacob Graff (1729–1778) of Lebanon descended in the family until the early twentieth century and, according to tradition, stood in the kitchen. One of the earliest known Pennsylvania German tall-case clocks, it dates to about the time Michael Miller acquired the house. The case’s form and construction are overtly Germanic, with ample use of wooden pegs (rather than nails) and a trapezoidal pediment that appears on Continental furniture but is extremely rare in America. The clock’s eight-day movement features a moon phase dial, calendar wheel, and day-of-the-week disk (fig. 11). A walnut chest (fig. 12) with paneled lid in the Continental manner and a hanging corner cupboard with raised panel door (fig. 13) are also associated with the Miller house; details such as the notched corners of the raised panels on the chest and the shape of the raised panel of the cupboard door relate closely to the doors and shutters of the house.[5]

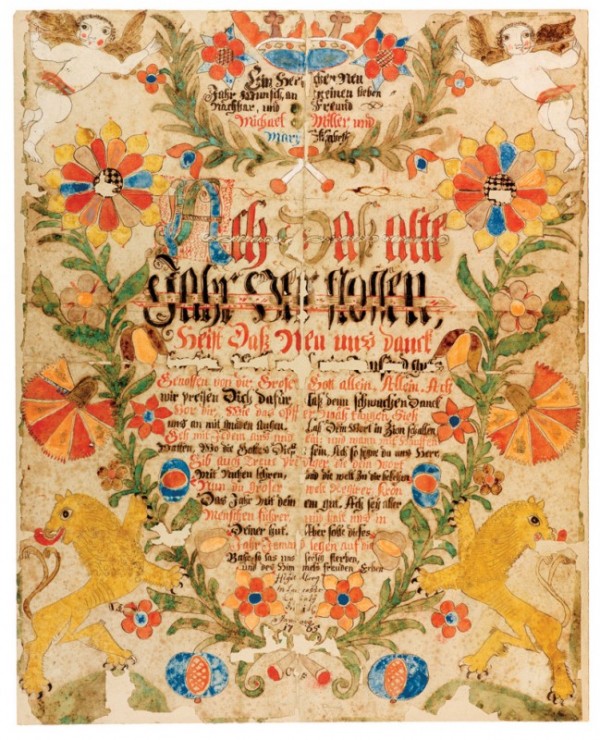

One of the most unusual objects associated with the house is an earthenware angel head (fig. 14) that was probably an architectural ornament. In 1765 Michael and Maria Elisabeth Miller were presented with a large New Year’s greeting (fig. 15), which is addressed to them as “my dear neighbors and friends.” The same artist also made a birth and baptismal certificate for the Millers’ son Johannes (John), born in 1766 (fig. 16). At the bottom of the New Year’s greeting are the initials “CF,” which stand for Caspar Feeman (Viehmann), who either made or commissioned this piece. Less than two miles from the Miller house stands the dwelling of Caspar’s brother, Valentine Viehmann (1719–1779) and his wife, Susanna, built in 1762 (fig. 17). The Viehmann and Miller houses share such details as massive carved summer beams and large attics. The Viehmanns’ attic also included a hoist system and large bin for storing grain. In 1778 Valentine and Susanna sold their property to their son Adam (1747–1815), who remained at that location until 1796.[6]

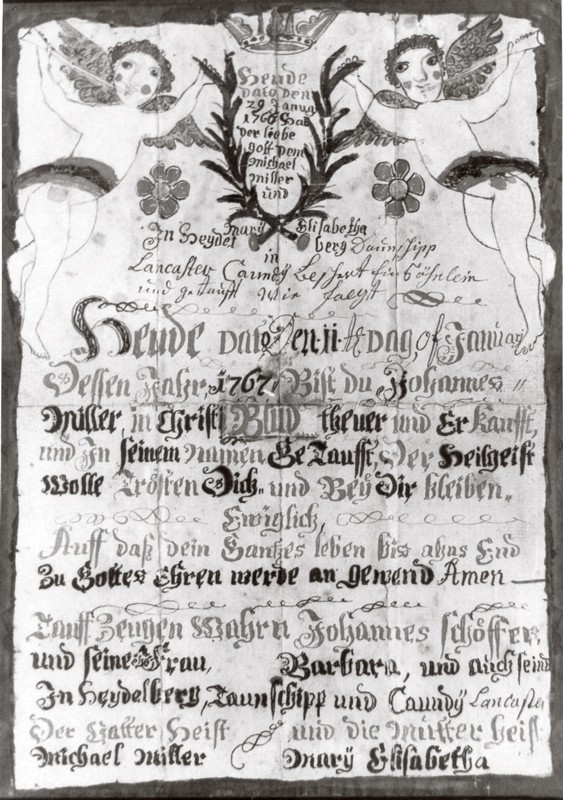

Michael Miller married Maria Elisabeth Becker (1736–1801) circa 1755. They had eight sons, four of whom predeceased them, and two daughters. Michael was an active member of the Millbach Reformed Church, serving intermittently as its treasurer, and his children were baptized and likely schooled there. Philip Erpf (1724–1803), a tavern keeper and prominent Schaefferstown resident, sponsored the baptisms of sons John Frederick and Philip; John Schaeffer (eldest son of Schaefferstown founder Alexander Schaeffer) and his wife, Barbara, sponsored son John (1766–1848); and Maria Catharina Miller (Michael’s mother) sponsored the youngest child, Maria Elisabeth (1775–1843). An elaborate certificate (fig. 18) made by fraktur artist Henrich Otto commemorated Maria Elisabeth’s baptism. Many of the motifs on this document relate to those inlaid on her chest, in particular the pomegranate with ruffled border. Little is known about Maria Elisabeth’s life between her baptism and the death of her father in 1815. She married Henry Schultze (born Henrich Christopher Emanuel Schultze; 1774–1824), probably before 1797, when the couple appear as baptismal sponsors for the daughter of Maria Elisabeth’s brother Frederick. Maria Elisabeth and Henry’s marriage was a union between two of the most preeminent Pennsylvania German families, the Millers being of significant wealth and the Schultzes of significant influence. Henry’s father, Emanuel Schultze (1740–1809), was the minister at Christ Lutheran Church near Stouchsburg, Berks County, from 1771 until his death in 1809, and his mother, Eve Elisabeth Muhlenberg (1748–1808), was the eldest daughter of Lutheran patriarch Henry Melchior Muhlenberg. Henry’s brother John Andrew Schultze (1775–1852) was a three-term member of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives; the first prothonotary, recorder of deeds, register of wills, and clerk of courts for Lebanon County, from 1813 to 1821; and a two-term governor of Pennsylvania from 1823 to 1829. Maria Elisabeth and Henry Schultze had no children, a fact that would play a role in her inheritance and, ultimately, the chest’s line of descent.[7]

Faced with a substantial estate and many heirs, Michael Miller prepared his last will and testament in 1809. In that document he mentioned 194 acres of land in Berks County given to his late son Benjamin; 94 acres in Tulpehocken Township, Berks County, given to his son Michael; 133 acres in Heidelberg Township given to his late son George; and 138 acres in Heidelberg Township given to his son Frederick (who would also predecease him). The elder Michael’s son Jonathan, a Philadelphia merchant, was to inherit £650, and his daughter Catherine, wife of Michael Gunckle, was to inherit £800. To his son John Miller, who had already received 300 acres of land along with the house and mill, Michael Sr. left a horse, two wagons, two plows, two harrows, “my Clock with the case,” a ten-plate stove and pipes, two still kettles of his choice and half of the distilling vessels, “and all my smith tools” but permitting “my son Fredk. and the heirs of my deceased son George to work with the said Tools in the smith shop.” To his youngest child, Maria Elisabeth, Michael bequeathed £150 outright (in addition to £300 that she had already received) and £600 to be put out at interest, for which she was to receive yearly dividends and payments of £150 at increments of eight, eleven, fourteen, and seventeen years after Michael’s death. If she was widowed, she was to receive the entire principal of £600 at once, but if her husband outlived her and they had no issue, the principal was to be divided among her siblings. Michael Miller appointed his son John as the sole executor.[8]

The careful wording of the bequest to Maria Elisabeth indicates that her father wanted to protect her inheritance from her husband. Although Henry Schultze came from a distinguished family, the archival record suggests that he was a bit of a ne’er-do-well. When Henry’s father, Emanuel Schultze, died in 1809, the inventory of the latter’s estate mentioned the sum from his “Family Book,” which listed what each of his children had received. Henry Schultze had been given £2,375.9.9—nearly triple the total of what his four siblings had together received. No record of Henry and Maria Elisabeth’s marriage has been found, which is surprising given the numerous ministers on his side of the family, nor have any deeds or estate papers for Henry Schultze come to light. Problems pertaining to inheritance began soon after Michael Miller’s will was recorded following his death in late 1815. In May 1817 Henry and Maria Elisabeth Schultze, along with her brother Jonathan Miller and his children Jonathan Miller Jr. and Catharine Miller, wife of Jacob Hiester, were named as defendants in a suit filed in the Lebanon County Court of Common Pleas “to try the validity of a Certain Instrument of Writing purported to be the last Will & Testament of Michael Miller.” The plaintiffs were John Miller; Catharine (Mayer/Meier) Miller, widow of George Miller (d. 1804); Catharine (Philippi) Miller, widow of Frederick Miller (d. 1811), and her daughter Catharine, wife of Daniel Strickler; and the heirs presumably of Benjamin Miller (d. 1814): Elisabeth Miller, wife of Andrew Kapp; and Catharine Miller, wife of Jonathan Mohr. Complicating matters further was the fact that John Andrew Schultze, Emanuel’s brother, not only was Lebanon County’s prothonotary and clerk of courts at the time but was also appointed by one of the defendants, Jonathan Miller, as his personal attorney in November 1816. A protracted legal battle ensued in which both sides hired attorneys and filed numerous appeals. Court documents include testimony that on September 28, 1816, all of the heirs discussed the validity of the will and that “John Miller had given the reasons why his brothers & sisters had got so small a portion.” The surviving witness to the will testified that he had met with Michael Miller on October 27, 1809, that following dinner Michael gave him instructions in German regarding his will, and that he then prepared Michael’s will in English and explained it to him in German. The court found in favor of the plaintiffs, but the defendants’ attorney filed a writ of error to move the case to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania. On October 11, 1817, the Supreme Court upheld the Court of Common Pleas decision and ordered the defendants to pay the plaintiffs $300.00.[9]

The Schultzes responded by filing suit against John Miller, seeking “amicable action in debt.” The court referred the case to arbitration, and three men were appointed to meet at Jacob Stouch’s tavern in Lebanon to review the case on January 30, 1818. According to the testimony, John Miller and his attorney “appeared at first but shortly thereafter withdrew.” The Schultzes then presented their case, arguing that £150 (or $400.00) had been bequeathed to Maria Elisabeth by Michael Miller and was to be paid within two years of his death, that his executor John Miller had “neglected & refused” to do so, for which the Schultzes sought the £150 “with lawful interest.” In addition, the Schultzes claimed that Michael Miller was indebted to them “for the work and labor care and diligence of the said Maria . . . as nurse for the said Michael Miller in his lifetime and at his special instance and request in and about the nursing and taking care of him the said Michael Miller whilst he was sick & laboring under divers maladies and diseases.” Furthermore, “being so indebted he the said Michael Miller” had promised on September 1, 1815, to pay Maria Elisabeth the sum of $1,500.00 but died before doing so, and John Miller refused to honor the debt. The arbitrators decided in favor of the Schultzes and ordered John Miller to pay them $1,002.50 ($602.50 “for the attendance of Mrs. Shultze upon her father in his sickness” and $400.00 “as the Legacy in the Will what is Due”), plus court costs. On January 31, 1818, John Miller’s attorney filed an appeal and the case went before the Lebanon County Court of Common Pleas. No record of the court’s decision has been found, but the final administrative accounts of Michael Miller’s estate submitted by John Miller indicate that the Schultzes were paid $602.50.[10]

Henry Schultze died in 1824 and was buried at the Millbach Reformed Church. Soon after his death, Maria Elisabeth and her brother John Miller appear to have resolved their differences. Widowed and childless at the age of forty-nine, Maria Elisabeth moved back to Millbach by 1830 to live with John, who since 1808 had been a widower. She is listed in both the 1830 and 1840 censuses directly before his name. In 1827 and again in 1834, she stood as a baptismal sponsor at the Millbach Reformed Church for two of her great-nieces. Maria Elisabeth died in 1843 and was buried at Millbach beside her husband. Her tombstone identifies her as both the wife of Henry Schultze and the daughter of Michael Miller—nearly thirty years after her father’s death. The inventory of her estate totaled more than $1,400.00 and indicates a well-appointed household, including carpet and window curtains; three looking glasses; a stove and pipe; numerous books and two pairs of spectacles; twelve silver teaspoons (six of them German) and “Flowered Glass”; five “Profiles”; an orange tree, flowerpots, garden seed, and eleven chickens. Her furniture consisted of two bureaus and a small case of drawers; two dining tables, twelve chairs, and an armchair; three bedsteads; a thirty-hour clock, corner cupboard, and queensware; two dough troughs and a kitchen cupboard; quilting frames, two spinning wheels, and a wool wheel; “1 Trunk” valued at $1.00, and “2 Chests & 1 Box &c &c” valued at $2.00. On February 27, 1843, Maria Elisabeth prepared her will, beginning it with the date and the word “Mülbach.” This brief document, written by her own hand in German script, noted, “the household goods my brother Johannes shall keep what he can use,” and the leftover items were to be divided into four portions among his three daughters (Catharine, 1792–1869, m. Jacob Weigley; Sara, 1797–1870, m. William Forry; and Martha, 1802–1885, m. George Zeller) and the children of his deceased daughter Maria Magdalena (1789–1841, m. George Becker). The will also bequeathed a $1,200.00 bond to be divided between her brothers John and Jonathan Miller. Most significantly, the administrator’s account included a credit of $198.54 “for the Articles bequeathed to the daughters of John Miller & included in the Inventory.” One of these items was almost certainly the inlaid chest (fig. 1).[11]

Five years after Maria Elisabeth died in 1843, John Miller passed away and his executors sold the Millbach property to the Illig family. The inventory of John Miller’s belongings lists a silver watch and three items that likely represent the same objects in his father Michael’s estate: “1 clock & case” (probably the one made by Jacob Graff), a “Pianno Forte” (probably the “spinet”), and “old Blacksmith tools.” John Miller’s wife, Anna Catharina, had died in 1808, leaving him to finish raising their four daughters. Sara, born in 1797, was the recipient of a birth and baptismal certificate (fig. 19) that shows the family’s continued adherence to Germanic cultural traditions. In addition to the certificate made for John Miller (fig. 16), a colorful certificate with trumpeting angels was made for John Miller’s wife, Anna Catharina Lescher, by schoolmaster Johann Conrad Gilbert. Although this certificate documents her birth in 1768 (fig. 20), it was probably not made before the early 1780s, when Gilbert moved to Tulpehocken Township, Berks County. For some time before his death, John Miller shared the house with his daughter Catharine and her husband, Jacob Weigley (1789–1880). The Weigleys had ten children. One of their sons, William M. Weigley (1818–1887), married Anna Rex (1808–1900), great-granddaughter of Schaefferstown founder Alexander Schaeffer. William M. Weigley made a fortune in the mercantile business and in 1883 erected a brownstone mansion in Schaefferstown so grandiose that it was published in Godey’s Lady Book. Following Maria Elisabeth’s death, the chest likely went to her niece Catharine (Miller) Weigley, although no documentation exists to confirm this. However, the serendipitous discovery of a notation made by a later descendant reveals the subsequent line of descent. The next documented owner was Catharine Miller Weigley’s eldest daughter, Mary (1811–1898), who never married. Four years before her death, Mary gave the chest to her niece Emma (b. 1865), daughter of her youngest brother John (b. 1832). This is documented by a note in a ledger kept by Emma’s brother Walrow, who, on March 15, 1894, wrote, “Emma got great-grandfather Miller’s sister’s chest from Aunt Mary.” This notation provides conclusive evidence of this line of descent and indicates that the chest was regarded as a family heirloom. Emma Weigley most likely left the chest to her sister Westa (1859–1934), who lived near Millbach in Richland Borough, Lebanon County. The inventory taken of Westa Weigley’s belongings in 1935 includes what appears to be a short list of family heirlooms: a “Grandfathers clock” valued at $100.00; sideboard, $7.50; sofa, $3.00; marble-top table, $1.00; teapot and two pitchers, $1.00; and “Trunk” valued at 25 cents.[12]

What happened to the chest after Westa’s death in 1934 is unknown, but its history had been forgotten by 1969, when it was offered in the sale of Pennsylvania collector Perry Martin. The auction catalogue described it as an “Extremely rare Chester County Dower Chest with raised panel, inlaid with closed tulips, hearts, daisy, tulip trees, and vines and berries . . . the only known chest of this kind.” No doubt the Chester County attribution was based on the style of the inlaid decoration, which bears a resemblance to the line-and-berry inlay used on furniture owned primarily by Chester County Quaker families (fig. 21). The appearance of similar inlay on the Miller chest raises questions about potential cross-cultural influences, possibly introduced by Quakers who began moving into German-speaking areas of Berks County as early as the 1730s, when the Exeter Friends Meeting was founded by Welsh Quakers from the Gwynedd Monthly Meeting. Whatever the inspiration for the inlay, the revelation of Maria Elisabeth Miller’s identity enables the chest to be more fully understood as a product of the Tulpehocken Valley—a region long noted for its extraordinary Germanic architecture but heretofore with little known about its furniture.[13]

The Tulpehocken Valley

Derived from an Indian word meaning “land of turtles,” the Tulpehocken Valley is a fertile region that extends across what is now western Berks and eastern Lebanon Counties, bounded by the Blue Ridge and South Mountains and containing approximately 322 square miles or 206,000 acres (fig. 22). Much of the valley was originally part of Heidelberg Township, Lancaster County. The Tulpehocken Creek, of which Mill Creek is a major tributary, is the largest stream in western Berks County, rising just west of Myerstown and flowing east approximately twenty-six miles to join the Schuylkill River at Reading. Approximately 95 percent of the original Tulpehocken settlers were of German heritage, a fact that was reflected in the region’s early architecture, such as the house built in 1745 for Heinrich Zeller (figs. 23, 24). Many had settled initially in the Schoharie Valley of New York but relocated to the Tulpehocken region in response to an invitation in 1722 by Governor William Keith of Pennsylvania. In 1723 some fifteen to eighteen families from Schoharie traveled southward along the Susquehanna River, then east along the Swatara Creek to its juncture with the headwaters of the Tulpehocken. The early Tulpehocken inhabitants were of diverse religious backgrounds. From 1729 to 1743 Lutheran, Reformed, and Moravian factions competed for influence in a period known as the “Tulpehocken Confusion.” The arrival of Lutheran minister Henry Melchior Muhlenberg in 1742, followed by Reformed minister Michael Schlatter in 1746, and their efforts to organize churches and provide ordained ministers helped settle this matter.[14]

Many contemporary observers remarked on the agricultural prosperity and Germanic character of the region. In 1783 German physician Johann David Schoepf wrote, “We crossed Tulpehacken Creek, and passed through a part of the Tulpehacken valley, an especially fine and fertile landscape . . . the inhabitants are well-to-do and almost all of them Germans.” The 1790 census reveals that Schoepf was quite accurate in his observation: Berks County was 85 percent German, while Lancaster County was 72 percent and Dauphin County 52 percent. When Theophile Cazenove traveled in 1794 from Womelsdorf to Myerstown, he was astounded by the clothing worn by the local inhabitants, writing, “It seemed to me I saw people coming out of church in Westphalia, so much have all these farmers kept their ancestors’ costume.” In 1829 Philadelphia antiquarian John Fanning Watson traveled through the “Tulpehocken Country,” which he described as “a rich valley country—with high mountains in the distant views. The Cultivation & Scenery always fine. . . . The whole face of the Country looks German—All speak that language, & but very few can speak English. Almost all their houses are of squared logs neatly framed—of two stories high. The barns are large & well-fitted,—generally constructed of squared Logs or stone, but all the roofs were of thatched straw.” The region’s fertile and well drained limestone soil was responsible for the agricultural prosperity, and Tulpehocken Creek supported the development of numerous milling operations as well as an iron furnace. Founded in 1749 as the Tulpehocken Eisenhammer and later renamed Charming Forge, the site remained in operation until 1895. George Ege acquired the furnace in 1783 and erected a stately mansion with interior woodwork rivaling that of elite Philadelphia town houses (fig. 25). His son Michael Ege married Margaretha Schultze, a sister-in-law of Maria Elisabeth Miller. In the 1820s Tulpehocken Creek became part of the Union Canal system, built to connect the Schuylkill Canal at Reading to the Susquehanna River at Middletown. One of the first canals in the United States, the Union Canal brought great prosperity to Lebanon County before the advent of the railroad.[15]

Millbach, settled in the 1720s, was one of the earliest communities in the Tulpehocken Valley. About four miles to the northwest was Myerstown, founded in 1768. Four miles to the northeast was Womelsdorf (est. 1762), the home of Conrad Weiser (1696–1760), a renowned Indian interpreter and treaty negotiator, justice of the peace, and father-in-law of Henry Melchior Muhlenberg. Just west of Womelsdorf were the town of Stouchsburg and Christ Lutheran Church—one of the most affluent congregations in Pennsylvania in the 1700s and the center of a large parish that was made up of from five to nine congregations in Berks, Lebanon, and Lancaster Counties (fig. 26). Founded in 1743, Christ Lutheran was one of the first churches in Pennsylvania to have an organ, commissioned in 1752 from Moravian Johann Gottlob Clemm of Philadelphia for the staggering amount of £127.3.4 (to which Valentine Viehmann contributed). One of the largest settlements in the area was Schaefferstown, laid out in 1758 by Alexander Schaeffer (1712–1786) and initially known as Heidelberg. The illiterate son of a poor German peasant family, Alexander Schaeffer immigrated in 1738 and became a highly successful entrepreneur and landowner by the time of his death. He lived on a farm adjacent to the town, where he built and operated a tavern known as the King George. Schaefferstown grew rapidly after its founding. In 1759 the inhabitants began one of the first public water works in the country, using underground wooden pipes to carry water to two fountains on Market Street. A market house was erected near the center of town, used primarily during the annual cherry fair, which remains in operation to this day. In 1783 the Schaefferstown tax list included a locksmith, blacksmith, nailsmith, mason, miller, tanner, saddler, baker, three carpenters, three tailors, three shoemakers, and six weavers. By 1798 the town’s population approached five hundred people.[16]

Soon after Schaefferstown was laid out, the Lutheran and Reformed inhabitants built a log structure to serve as a shared or “union” church and schoolhouse. The arrangement did not last long. In 1765 the Lutheran congregation sold its interest in the log church to the Reformed congregation, which used it until 1795, when it was replaced by a stone church. Between 1765 and 1767 a new Lutheran church was built, later known as St. Luke, using gray limestone with contrasting red sandstone quoins and architraves (fig. 27). This style of stone construction was repeated throughout the Tulpehocken region on other churches as well as prominent houses such as that of the Millers, providing a visual cohesiveness to the region’s elite architecture. A unique feature of the new church was the three carved winged angel heads (fig. 28) attached to the cornice, which were likely removed when the building was remodeled in 1884. Dragon heads were also reputed to have been part of the building’s woodwork. A committee that included local innkeeper Philip Erpf oversaw the construction, led by master builders Henry and Philip Pfeffer, who inscribed the sounding board above the wineglass pulpit: “Heinrich Pfeffer, Philip Pfeffer, Schreiner, haben diese Kirche Arbeit gemacht in Juny Monat 1767” (Henry Pfeffer, Philip Pfeffer, Carpenters, have built this church. Made in month of June 1767). Henry Melchior Muhlenberg preached to a large crowd gathered for the dedication of the church in 1769 and described the building as “one of the best in this land, built of massive stones, large, well laid out, and adorned with a tower.” In 1770 his son Frederick Muhlenberg (1750–1801) became minister of St. Luke. Arriving in the Tulpehocken region after spending seven years in Germany, Frederick wrote that “the Tulpehocken people may be regarded as quite genteel.” In 1771 he married Catharine Schaeffer, daughter of a wealthy Philadelphia sugar refiner. Frederick served as pastor of St. Luke until 1773, when he accepted a call to New York City. He later left the ministry for politics and in 1789 became the first Speaker of the U.S. House. His sister, Eve Elisabeth Muhlenberg, married Lutheran minister Emanuel Schultze, the father-in-law of Maria Elisabeth Miller.

Another renowned Schaefferstown-area inhabitant was ironmaster and glassmaker “Baron” Henry William Stiegel, who emigrated from Germany in 1750 along with his mother and brother Anthony. Stiegel married the daughter of Jacob Huber, owner of the Elizabeth Furnace located some five miles south of Schaefferstown near Brickerville, and engaged in iron manufacture. In 1762 he founded the town of Manheim, Lancaster County, where he established a short-lived glassworks and built a large brick house that is reputed to have had imported Dutch tiles, tapestries and scenic painted landscapes on the walls, and a chapel. In 1769 Stiegel built a seventy-five-foot-tall wooden tower on a hilltop outside Schaefferstown to use for entertaining. Local legend maintains that his visits were heralded by trumpet players and his departures by cannon so the next destination was forewarned to prepare.[17]

The discovery of the Maria Elisabeth Miller chest and its history of ownership provides a starting point from which to explore the furniture of the Tulpehocken Valley. Several other examples of inlaid furniture have been found that relate to the Miller chest, as well as a large group of chests with painted decoration, long associated with the so-called Embroidery Artist. Genealogical research has identified many of the chests’ owners and linked them to the Tulpehocken region. Most of the families had ties to the Millbach Reformed Church, St. Luke Lutheran Church, or Christ Lutheran Church. Through an in-depth analysis of this group of furniture, distinctly local patterns of decoration and construction emerge that shed light on the furniture-making traditions of the Tulpehocken Valley.

Related Inlay

Closely related to the Miller chest is another inlaid walnut example made for Magdalena Krall (fig. 29). As on the Miller chest, a separate lightwood plaque that contains the owner’s name is set into the façade (fig. 30). Magdalena Krall was the daughter of Christian and Catharine Krall of Elizabeth Township, Lancaster County. Her paternal grandfather, Ulrich Krall, emigrated from Germany in 1729. Tax and probate records reveal that the Kralls were of moderate wealth in comparison with the Miller family. In 1798 Christian Krall’s dwelling was assessed as a one-storey log house of 30 by 24 feet, described as “old but in good repair.” The inventory taken at the time of his death in 1802 lists a case of drawers valued at £1.2, a clothespress at £5, a house clock at £8, a corner cupboard at £7.10, as well as queensware, pewter, grain, and livestock. The total value of his inventory was £1,283.17.10. The Kralls were likely Mennonite, as their name is absent from local church records, and about four miles west of Schaefferstown was the Krall’s Mennonite Meetinghouse, founded in 1811. Inlay related to that on the Krall chest appears on another walnut chest with two drawers— inlaid on the façade “1794 / M B” within a rectangular surround from which a pair of undulating vines with leaves and tulips emanates—and several tall-case clocks, including one dated 1789 and another with a history of ownership in the Taylor family of Womelsdorf, Berks County (fig. 31). Inlaid motifs on the pendulum door echo those on the Krall chest, such as heart-shaped leaf and single-berry terminals and flowers consisting of a ring of dots surrounding a single dot (fig. 32). A third clock, with a history of ownership in the Illig family of Millbach, has the initials “PI” (or “PL”), inlaid above the pendulum door and is embellished with line-and-berry motifs, tulips, and stars (figs. 33, 34).[18]

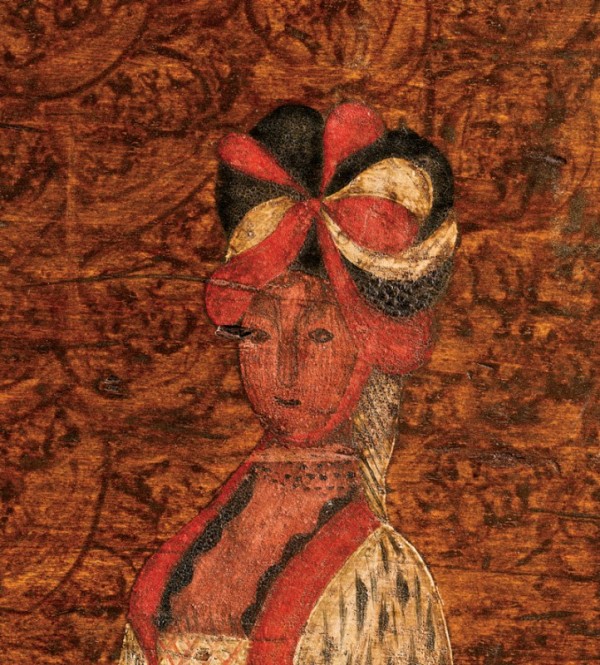

The Embroidery Artist Chests

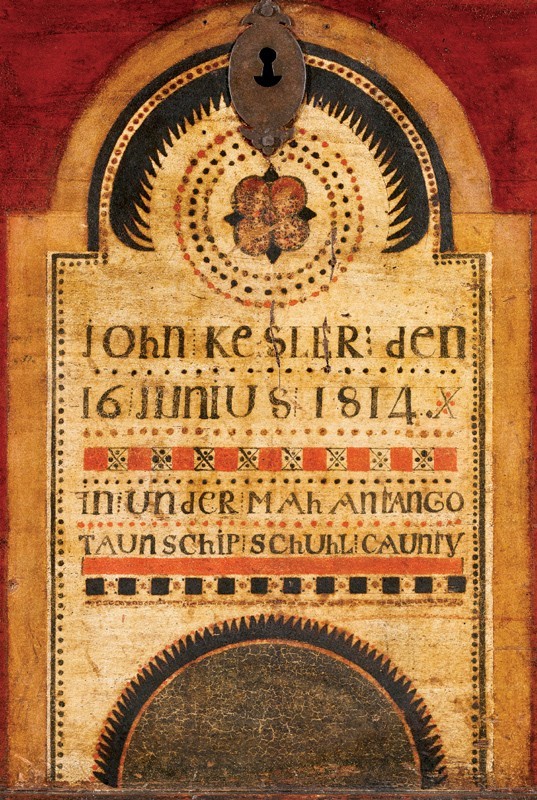

The Miller and Krall chests have several distinctive features of ornament, construction, and hardware that also characterize a group of paint-decorated chests associated with the so-called Embroidery Artist, of which more than twenty examples are known, ranging in date from 1788 to 1805 (fig. 35). Two basic models of painted decoration are found, the first having a large, horizontal panel across the façade, similar to the inlaid walnut chests, in which the owner’s name and the date are typically inscribed. The alternative design features a central heart flanked by two arched-head panels. The painted chests are made of tulip poplar or pine and have typical Germanic construction details including the use of wooden pegs to attach the moldings and wedges driven into the end grain of the pins to secure the dovetails. Several more notable construction features are found on the Embroidery Artist chests that help provide a set of defining characteristics. Thirteen of the chests (in addition to the Miller example) have till lids with a stepped molding running down the center, rather than the typical flat board with molded edge (fig. 36). This detail, which has not been observed on any other group of chests, required the craftsman to remove nearly half the thickness from one side of the board and use a molding plane to finish the resulting lip. Another feature that often appears on the underside of the lid and interior of the chest is a tapering spiral motif, made by the craftsman in a red crayon to mark the inside of each board (fig. 37). The maker also typically marked the inside of the front and back boards in red to indicate the placement of the bottom edge of the till lid, as a guide for the two mortises he had to chisel out to hold the front board of the till compartment. Most of the chests have straight bracket feet, which extend from the base molding, and were built without glue blocks. Many of these unsupported feet broke over time and were replaced, sometimes with ball feet. The only known exception to this construction is the Miller chest, which has short ogee bracket feet that are supported by an oak batten that runs front to back at either side.[19]

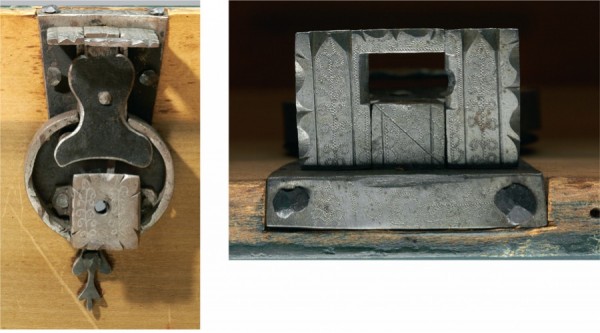

The hardware of the chests is also unusual and related. Ten chests, including the walnut one made for Magdalena Krall, have identical wrought-iron carrying handles consisting of two quatrefoil backplates and a bale with a pair of incised lines at the center (fig. 38). Another common feature is the locks, eight of which have decorative wrigglework engraving—some with dates and/or initials. Although chest locks are commonly found with decorative filework, locks with wrigglework engraving are highly unusual; thus, the presence of this feature on so many chests in this group is extraordinary. The three locks that are dated correspond closely to the date on the chest. The lock on the Catharina Lebenstein chest, dated 1789, is inscribed “HS 1788” (fig. 39). The Henrich Schorck chest, dated 1793, has a lock inscribed with the same date, as does the Susanna Zwally chest with a lock inscribed “17 IS 94.” The undated locks range from the lock on the Miller chest, which has a small wrigglework flower between the initials “HS,” to that on the Peter Rammler chest, which is embellished with profuse wrigglework on both the top and side and inscribed with the initials “IS” (fig. 40).[20]

The painted ornament on the chests is quite similar. A pomegranate appears inlaid on the Miller chest and on many of the painted examples (fig. 41). Another typical design is a simple flower formed by multiple light-colored dots, surrounding a darker central dot (fig. 42). Because of the elaborate nature of the painted decoration, the overall pattern was laid out first with a compass and straightedge. Many of the designs were then drawn on with a fine brush or pen. Scribe lines were also used to help align the lettering of the names, which were typically rendered in elaborate fashion with many calligraphic flourishes (fig. 43). Fine lines were used to embellish the decoration and inscriptions on many of the chests, such as cross-hatching within the pomegranates and between the two vertical strokes of the “1” in the dates.

Variations in the painted decoration and lettering on the chests indicate that three or more decorators may have been involved in their production. Construction differences also help to subdivide the chests further. The largest group (A) is characterized by the use of till lids with a stepped molding, straight bracket feet without glue blocks, and red spiral motifs drawn on the inside of the boards. This group has painted decoration in two different formats, one having a long, horizontal panel with ovolo ends, the other a central heart flanked by arched-head panels. Six of the chests in this group have identical carrying handles, and five retain their original locks with wrigglework ornament. The second group (B) is made up of five chests, each of which has the same type of till lid as group A, along with the additional feature of two small drawers under the till (fig. 44). Only one of the five chests in group B has the iron carrying handles, and none has ornamented locks (although one lock is missing). Group B chests have straight bracket feet, with further embellishment on two examples that have cusps and two with a dentilled base molding. The painted decoration on all five group B chests consists of arched-head panels flanking a central heart but differs from the group A chests in the use of urns within the arched-head panels and the placement of the date flanking the central heart rather than within it. The smallest group (C) includes three chests, which have the same carrying handles as many of the group A chests but differ in that they have flat rather than molded till lids. On the whole, these three groups of chests share a distinctive set of construction details, hardware, and painted decoration—suggesting that they were made in a limited geographic area, if not a single shop, and providing a strong rationale for considering them as one body of evidence. New research on the owners of the chests, none of which has survived with a solid family history, reveals their common origin in the Tulpehocken region and provides a starting point from which to explore the potential makers and decorators of the chests.[21]

GROUP A

The earliest known chest is dated 1788 and bears the name “Maria Stohlern” within the central heart (fig. 45). This chest was recorded by the Index of American Design in 1938 and is one of the most widely published Pennsylvania German examples. Maria Stohler was born in 1761 and grew up on a farm about two miles north of Schaefferstown, near Reistville. Her father, Johannes Stohler (1714–1785), immigrated in 1749 and married Anna Maria Glassbrenner in 1759. Stohler was a wealthy man at the time of his death; his inventory lists eighteen pewter plates and dishes; nearly four dozen pewter spoons, half of them new; and extensive linens, including nineteen tablecloths. His daughters Maria and Magdalena were each bequeathed £106—the same as their sisters Ann and Elisabeth had already received, likely when they married. Maria was given an additional £5 and a new side saddle. Three years after her father’s death, she received the chest. Circa 1790 Maria married John Shenk (1740–1814), a wealthy Mennonite widower who was twenty-one years her elder. Shenk owned a substantial stone house and several hundred acres in an area of Heidelberg Township known as Buffalo Springs. His estate inventory totaled £3,153, of which £1,678.8 was “Cash in the House.” To Maria he bequeathed £1,000 along with the right to use the house, new kitchen and cellar, “Two good Beds and Bedsteads, all my Linen Cloath my two Copper Kettles all my Pewter Ware and Kitchen Furniture, as also all my China Glass Delph and Silver ware in my Corner Cupboard together with the said Cupboard . . . one Cloaths Press . . . House Clock and Case and Ten Plated Stove” and her choice of kitchen furniture. In addition, Maria was to receive an allowance of £36 annually for “cloathing and boarding” his son Christian. John instructed his sons John and Joseph to keep the house in good repair and provide their stepmother with food and firewood and appointed as sole executor “my trusty Friend Samuel Rex,” storekeeper in Schaefferstown. Maria outlived her husband by twenty-one years and died in 1835. Her niece Sarah Stohler (1809–1880) was the owner of a small dome-top box with related painted decoration and inscribed with her name and the date, 1828, on the top in elaborate lettering (fig. 46). A closely related flat-top box inscribed for Johanna Kunger and dated 1827 has geometric designs identical to those on the drawers and façade of the Maria Stohler chest (fig. 47).[22]

The next chest in the group is dated 1789 and was made for Catharina Lebenstein (1774–1828) (fig. 48). This object retains its original hinges with tulip-shape terminals (fig. 49), carrying handles (fig. 38), and wrigglework-decorated lock bearing the initials and date “HS 1788” (fig. 39). Catharina was born on January 12, 1774, to David Lebenstein Jr. (1736–1789) and Elisabeth Hock, who married in 1762. According to family tradition, her father was born aboard the ship Princess Augusta en route from Europe. Immigration records list a David Löebenstein, aged forty, among the ship’s passengers, along with such Schaefferstown-area settlers as Gottfried Lautermilch, Bastian Stoler, Durst Thoma; Sebastian, Jean, and Diederich Gackelie; and Hans Zwally. Two David Lebensteins appear in the 1759 tax list for Heidelberg Township, the younger listed as a freeman (single man over age twenty-one). The Lebensteins settled in Millbach, on land next to Michael Miller and the Viehmanns, where they joined a small group of German Baptists or Dunkards (so called for their practice of full-immersion baptism) who in the 1720s established a settlement in Millbach. David Lebenstein Sr. died sometime before 1771, when only David Jr. appears in the tax list. David Jr. died in 1789, having prepared copies of his will in both English and German in which he described himself as “being very Sick and weak in Body.” His inventory included farm equipment and livestock; a loom, forty yards of linen and tow; a house clock valued at £6.10; and pewter plates, dishes, and a basin worth £2. To each of his three daughters he bequeathed a £120 share in his estate. Catharina Lebenstein married John Royer (1765–1839) of Heidelberg Township, with whom she had seven children. In the 1798 direct tax list, her mother, “Widow Lebenstein,” appears as a member of John Royer’s household. The tax list also indicates that John Royer was a prosperous farmer and owned nearly two hundred acres of “good limestone land” with a “new and well finished” stone house of 40 by 31 feet along with two smaller hewn-log houses; a small log stable; and a large stone-and-log barn. Catharina died in 1828 and John in 1839; they are buried at the Millbach Brethren Meetinghouse along with her parents. The inventory of John’s estate included a weaving loom, anvil and smith tools, farm equipment, and one “Chist”—possibly the one made for Catharina.[23]