Mug or “cann,” mottled slip decoration, England, ca. 1685–1695. Slipware. H. 4". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources and Jamestown Settlement, Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

“Canns,” mottled slip decoration, England, ca. 1685–1695. Slipware. (Right) H. 5". Catalog nos. COLO J 47308 (left) and COLO J 11806 (right). (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

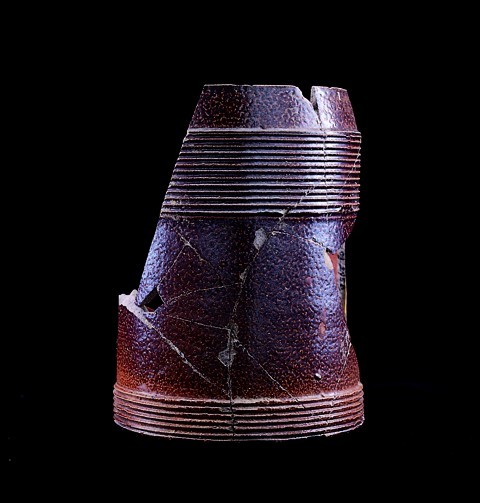

Detail of “squab” handle terminal, England, ca. 1685–1695. Slipware. COLO J 11806. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Mug, Fulham, England, ca. 1685–1695. Brown salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources and Jamestown Settlement, Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Closely resembling the form of the mottled slipware “canns,” this archaeological example also was found at the William Drummond site in James City County, Virginia.

During the early 1980s, state archaeologists working on the William Drummond plantation site in James City County, Virginia, recovered two unusual cylindrical mugs or “canns” from circa 1690 archaeological contexts (fig. 1). Subsequently, two other examples that had been previously excavated were identified in the National Park Service archaeological collections at Jamestown (fig. 2). Unfortunately, these examples had been excavated decades earlier and information concerning their recovery had been lost. More recently, fragments of two more of these curious canns have been found in other nearby archaeological sites.[1]

Although stoneware vessels of this general form were manufactured in large quantities during the late seventeenth century, in and around London, these particular canns are unusual because they are earthenware. The clay body is very fine grained, red clay with small white ecks and frequent gray and orange streaks. The vessels were wheel thrown and trimmed on the lathe resulting in an exquisitely thin product. Multiple horizontal reeded bands ornament the exterior just below the rim and above the base. Flattened and ovoid-sectioned with a central groove, their extruded vertical strap handles end at the bottom with a well-formed “squab”-terminal (fig. 3).[2]

The exterior of the canns were spattered all over with two or three colors before they were glazed, creating a “marbled” appearance. A thin matte and finely crazed lead glaze gives the fabric a reddish-brown appearance. The most intact example from Jamestown, although partly discolored from exposure to fire, is decorated with splashes of dark manganese appearing blackish brown, and a grayish white, possibly tin, oxide. The other Jamestown example is similarly decorated, but includes also a light cobalt blue, which is probably a mixture of cobalt and tin oxides. The Drummond site canns have splashes of manganese appearing brown, white, probably from tin oxide, and green from copper oxide.

These six vessels from the Jamestown environs comprise the only recorded examples of this ware. They appear to represent a rare and highly experimental period in English ceramic production. In the late seventeenth century, John Dwight of Fulham, and the Elers brothers of Staffordshire and Vauxhall, are best known for their pottery experiments, as well as their legal disputes. In terms of form and skill of manufacture, the canns closely resemble John Dwight’s brown stonewares produced after 1685, but do not match any of the known Fulham examples (fig. 4).[3] Furthermore, Dwight is not known to have worked in red earthenware. The canns are wheel thrown rather than slipcast, thus lessening the likelihood of the Elers’ Staffordshire pottery as the source.[4]

During this period of experimental pottery manufacture, similar decorative techniques are demonstrated on other wares. For example, a unique gray salt-glazed stoneware Fulham gorge circa 1680 in the Victoria and Albert Museum is splashed with oxides of iron brown and cobalt blue. Also, some of Elers’ red and brown stonewares are decorated with enameling, as evidenced on a brown teapot also in the Victoria and Albert Museum.[5] An important inuence may have been the spattered cobalt technique known as bleu Persan or bleu de Nevers that was commonly used in the nearby London delftware factories during the 1680s, demonstrated by wasters found at Dwight’s kiln site.[6]

On June 20, 1693, Dwight filed a lawsuit contending that one of his laborers, John Chandler, had been lured away and revealed secrets to the Elers of Fulham, as well as other potters working in Nottingham and Burslem.[7] In John Dwight’s Fulham Pottery Excavations 1971–79, Chris Green states that Dwight employed “[a]t least one thrower of the highest abilities” from circa 1685 until 1695, and very guardedly conjectures that it was possibly Chandler, who worked there from 1683 to 1691.[8] The six earthenware canns found in and around Jamestown bear a strong resemblance to the Fulham stoneware mugs, suggesting a link with Dwight. Could they be examples of the unrecognized red stoneware Dwight is known to have produced?[9] Or did Chandler, whom Dwight sued for stealing secrets, share with others the sophisticated lathe turning technique employed in the manufacture of these six slip-decorated canns? If so, are they examples of the unidentified “browne muggs,” made at Elers’ London pottery at Vauxhall? Only time will tell, as we must await new research at other late seventeenth-century British pottery-manufacturing sites.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank David Riggs, Curator, and William Cahoon, Museum Technician, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park; and Thomas Davidson, Curator, Jamestown Settlement, Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation for making the vessels available for study and photography. For sharing their opinions of the curious canns, I would like to thank Robin Hildyard, Jonathan Horne, Garry Atkins, Chris Green, Robert Hunter, and Ivor Noël Hume.

Merry Outlaw

New Discoveries Editor

<Xkv8rs@aol.com>

“Cann” was a common seventeenth-century ceramic term for tankard. Chris Green, John Dwight’s Fulham Pottery Excavations 1971–79 (London: English Heritage, 1979), p. 63.

Green, John Dwight’s Fulham Pottery Excavations, pp. 121–22.

Ibid.; Letter from Chris Green to Garry Atkins, 26 October 2001.

Gordon Elliot, John and David Elers and their Contemporaries (London: Jonathan Horne Publications, 1998), pp. 17–18.

Robin Hildyard, Brown Muggs: English Brown Stoneware (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1985), fig. 19, p. 37, fig. 48.

Green, John Dwight’s Fulham Pottery Excavations, p. 67.

Ibid., p. 333.

Ibid., p. 118.

Ibid., pp. 128–29.