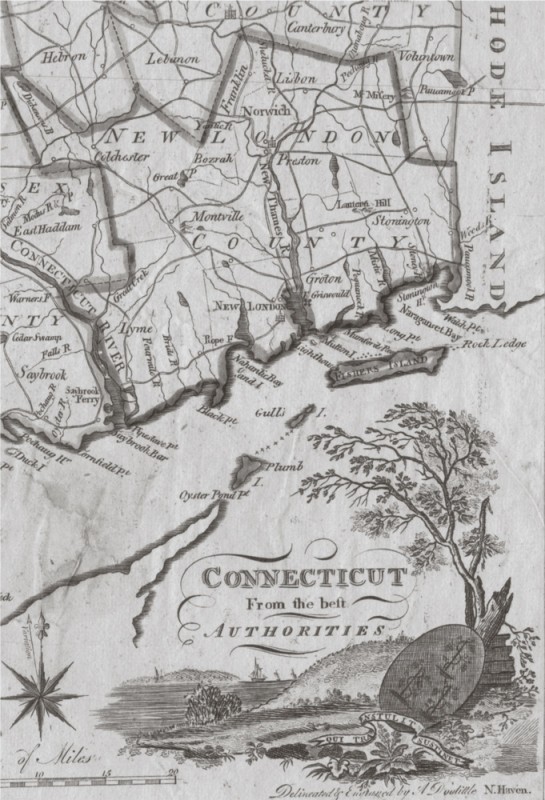

Detail of Amos Doolittle, Connecticut From the best Authorities, first printed by Matthew Carey, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1795. (Courtesy, Connecticut Historical Society.)

Desk, attributed to Felix Huntington, Norwich, Connecticut, 1775–1790. Mahogany and zebrawood with white pine. H. 43 1/4", W. 44 1/4", D. 22". (Courtesy, Art Institute of Chicago, gift of the Antiquarian Society through the Jessie Spalding Landon Fund, 1948.122.)

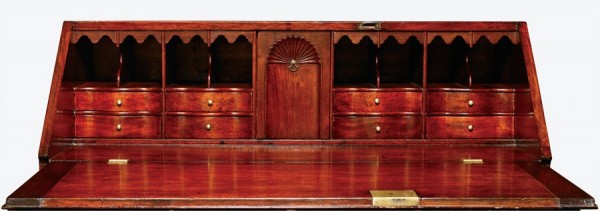

Desk illustrated in fig. 2 with the fallboard open.

Chest-on-chest, attributed to Ebenezer Tracy, Lisbon, Connecticut, 1796. Cherry with white pine, tulip poplar, birch, and chestnut. H. 81 1/4", W. 40 1/4", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Connecticut Historical Society, gift of Frederick K. and Margaret R. Barbour in memory of Newton C. Brainard, 1965.53.0; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This object is inscribed “Lisbon / 1796.” The feet and base molding are restored.

High chest, attributed to Jesse Birchard, Norwich (Bozrah), Connecticut, 1770–1790. Mahogany; secondary woods not recorded. H. 84", W. 36 3/4", D. 21 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Walton Antiques.)

Chest-on-chest, American, Norwich area, Connecticut, 1770–1800. Cherry; one original finial; replaced brasses. H. 95 1/2", W. 46", D. 23 1/4". (Courtesy, The Baltimore Museum of Art: Dorothy McIlvain Scott Collection, BMA 2012-287; photo, Miitro Hood.)

Desk, attributed to Felix Huntington, Norwich, Connecticut, 1775–1790. Mahogany with white pine and tulip poplar. H. 43 1/2", W. 44", D. 22 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the desk illustrated in fig. 7 showing the fallboard open. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left shell on the fallboard of the desk illustrated in fig. 7. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the center shell on the fallboard of the desk illustrated in fig. 7. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left front foot of the desk illustrated in fig. 7. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

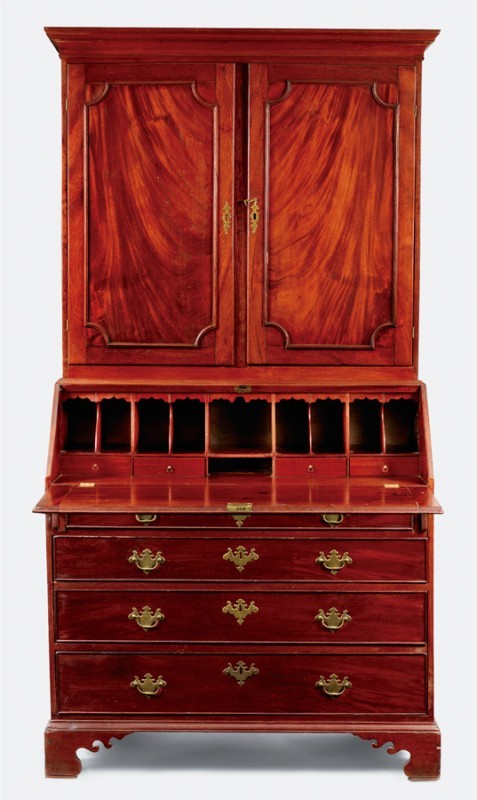

Desk-and-bookcase, attributed to Felix Huntington, Norwich, Connecticut, 1785–1800. Mahogany and cherry with white pine and tulip poplar. H. 83", W. 43 1/2", D. 20 1/4". (Courtesy, Scotland Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest of drawers, attributed to Felix Huntington, Norwich, Connecticut, 1785–1795. Cherry with white pine and chestnut. H. 34 1/2", W. 38 1/2", D. 19 1/2". (Courtesy, Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest of drawers, attributed to the shop of Felix Huntington, Norwich, Connecticut, 1795–1805. Cherry with white pine and chestnut. H. 35 1/2", W. 38 1/2", D. 19". (Private collection; photo, Sotheby’s.)

Chest of drawers, attributed to Felix Huntington, Norwich, Connecticut, 1775–1790. Mahogany with white pine and chestnut. H. 32", W. 37 1/2", D. 21 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Sotheby’s.) The design of this chest is essentially the same as that of the lower section of the chest-on-chests illustrated in figs. 17 and 22. The faces of the front feet differ from those of the chest-on-chests in having a quirk bead rather than rounded beading. The chest is unusually small with a 33-inch case width and an elegant molded top with generous overhang and rounded corners.

Detail of the foot blocking on the chest illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Sotheby’s.) The triangular blocking of the right front foot is original. The square blocking elsewhere is replaced.

Chest-on-chest, attributed to Felix Huntington, Norwich, Connecticut, 1775–1790. Mahogany with white pine and tulip poplar. H. 81 1/4", W. 40 3/4", D. 20". (Courtesy, Connecticut Historical Society, gift of Frederick K. and Margaret R. Barbour, 1960.7.12; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the right front foot of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 17. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a serpentine drawer from the lower case of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 17, showing the rounded and chamfered cutout for the lock. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

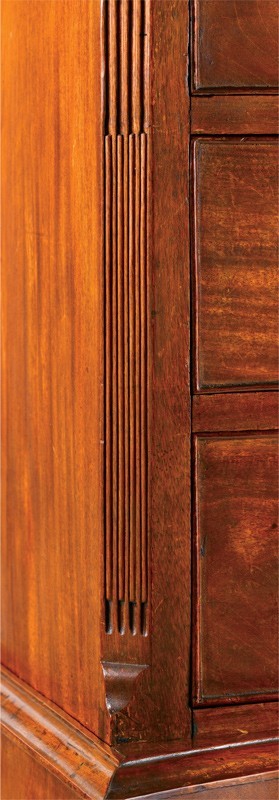

Detail of the left chamfered corner of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 17. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the bottom rail of the lower case of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 17, showing wooden pins used as fasteners. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest-on-chest, attributed to Felix Huntington, Norwich, Connecticut, 1785–1800. Mahogany with white pine, tulip poplar, and chestnut. H. 90 1/2", W. 41 1/4", D. 20 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Christie’s.) Pitched pediments are rare in Connecticut case furniture. Although different in design, the construction of this chest-on-chest is similar to the example illustrated in fig. 17. The finial, side plinths, and brasses are replaced.

Tall clock case, attributed to Felix Huntington, Norwich, Connecticut, 1785–1800. Mahogany with white pine and chestnut. H. 88 1/4", W. 20", D. 9 3/4". (Private collection; photo, David Stansbury.) The movement is by Nathaniel Shipman. The feet, fretwork, and finials are restored.

Detail of the right front corner of the clock case illustrated in fig. 23, showing chamfering and a lamb’s-tongue terminal similar to that on the chest-on-chest illustrated in figs. 17 and 20. (Photo, David Stansbury.)

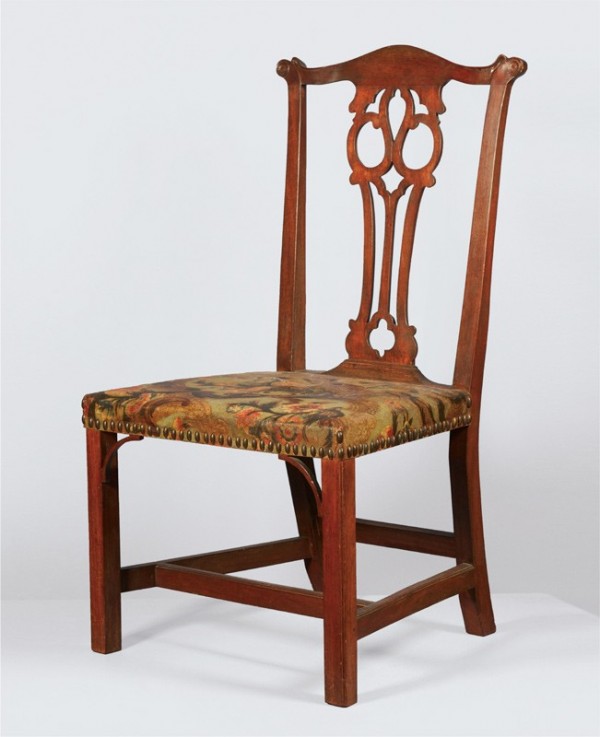

Side chair, attributed to Felix Huntington, Norwich, Connecticut, 1775–1795. Mahogany with maple. H. 37 1/2". W. 21 1/4", D. 17". (Private collection; photo, Nathan Liverant & Son Antiques.) The front knee brackets are missing, and the legs are pieced out at the bottom.

Side chair, attributed to Felix Huntington, Norwich, Connecticut, 1775–1795. Mahogany with maple. H. 37 1/4", W. 20 1/4", D. 16 1/2". (Courtesy, Leffingwell Inn, The Society of the Founders of Norwich, Connecticut, Inc., gift of Henry La Fontaine, #193; photo, Connecticut Historical Society.)

Side chair, attributed to Felix Huntington, Norwich, Connecticut, 1775–1790. Mahogany with maple and white pine. H. 38 1/4", W. 21", D. 17". (Courtesy, Lyman Allyn Museum, 1999.16.) Two chairs from the set represented by this example retain their original gilt leather upholstery and oval brass nails. A third chair was reupholstered between 1958 and 1990.

Detail of the spiral carving on the right crest ear of the side chair illustrated in fig. 27.

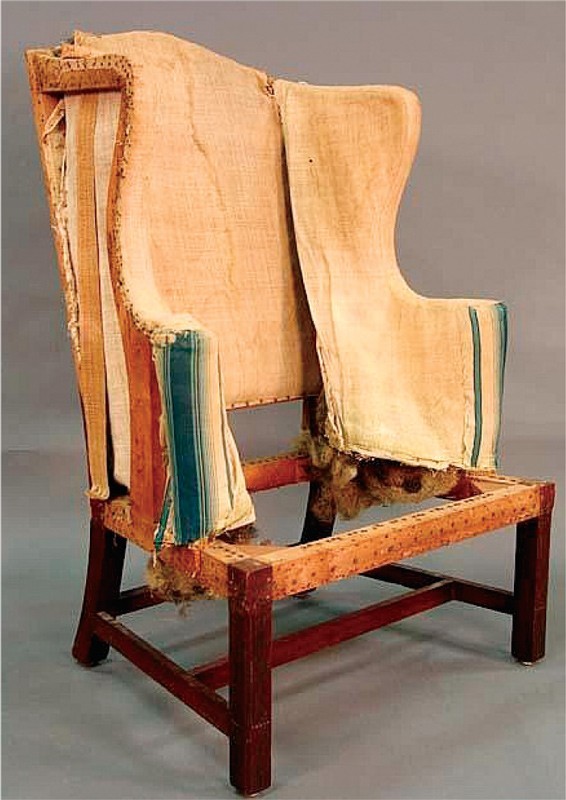

Easy chair, attributed to Felix Huntington, Norwich, Connecticut, 1775–1795. Mahogany with maple and white pine. H. 57", W. not recorded, D. 21". (Private collection; photo, Nadeau Auctions.) This chair has stop-fluted front legs with unusual chamfering at the corners. As with the blockfront desks (figs. 2, 7), the chair reflects strong Newport influence.

Desk, attributed to Nathan Clark, Norwich or Mansfield, Connecticut, 1785–1793. Mahogany and cherry with maple and white pine. H. 43", W. 42", D. 20". (Courtesy, Connecticut Historical Society, museum purchase in memory of Newton Case Brainard, 1966.85.0; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Located at the navigational head of the (New) Thames River (fig. 1), Norwich was the primary commercial center for the eastern half of Connecticut during the eighteenth century. The town’s merchants and seamen were heavily involved in the coastal, West Indian, and European trades, and imported goods “in the latest fashion” were widely available, both before and after the Revolution. With 7,325 inhabitants, Norwich’s population was second only to New Haven’s by 1782. Although Bozrah, Franklin, and Lisbon had been entirely within Norwich’s boundaries, they became independent towns in 1786; nonetheless, because of their proximity to Norwich, furniture produced in those towns is included in this study.

Eastern Connecticut furniture attracted little attention among early scholars. The Hudson-Fulton exhibition of 1909 included, without attribution, a shell-carved, blockfront desk formerly owned by Ebenezer Huntington (1754–1834) (figs. 2, 3). Four years later, Luke Vincent Lockwood’s Colonial Furniture in America (2nd ed.) mentioned but did not illustrate a high chest bearing the inscription “made by Joshua Read of Norwich in the year 1752.” Between 1936 and 1965, Ada Chase published a series of articles on Norwich-area craftsmen. Although she singled out Ebenezer Tracy (1744–1803) and Felix Huntington (1749–1823) as probable makers of case furniture, Chase did not identify any examples of their work. Houghton Bulkeley, Connecticut’s premier furniture scholar of the 1950s and 1960s, published a list of Norwich cabinetmakers in 1964 but, with the exception of the Joshua Read high chest, was unable to link other makers with specific objects.[1]

The first attempt to assemble and exhibit a group of historic artifacts from Norwich occurred in 1965, when The Society of the Founders of Norwich and Friends of the Slater Museum mounted “Craftsmen & Artists of Norwich.” The exhibition featured a range of paintings and decorative arts, including forty-four pieces of furniture. A chest-on-chest (fig. 4) was tentatively attributed to J. Backus, presumably Norwich joiner and wheelwright John Backus (1740–1814). Of the eleven other objects illustrated in the exhibition catalogue, none would be considered of Norwich origin today.[2]

In the 1974 exhibition “New London County Furniture, 1640–1840,” Minor Myers and Edgar Mayhew attributed sixteen pieces of case furniture and half a dozen chairs to Norwich and/or Colchester but, in every case, without an attribution to a maker. The authors did, however, note that the inscription “Lisbon/1796” on the chest-on-chest previously attributed to Backus was similar to writing by Ebenezer Tracy, best known as a Windsor chairmaker. Since Ebenezer and his son are the only cabinetmakers listed among Lisbon taxables in that year, the piece is almost certainly from the elder Tracy’s shop. The first publication to attribute seating other than branded Windsors to specific New London County shops was Robert Trent and Nancy Nelson’s “New London County Joined Chairs, 1720–1790” (1985). Their exhibition and catalogue identified two groups of chairs associated with the William Lathrop and Felix Huntington shops. These sources were the primary references for furniture made in eastern Connecticut until 2005, when Thomas and Alice Kugelman and Robert Lionetti’s Connecticut Valley Furniture: Eliphalet Chapin and His Contemporaries, 1750–1800 identified the work of major Colchester shop traditions and established a base line for differentiating furniture produced in Norwich and other regional towns and communities.[3]

Late Eighteenth-Century Norwich Cabinetmakers

In addition to Felix Huntington, whose work is the principal focus of this essay, the checklist, compiled from various sources, lists approximately two dozen woodworkers active in the Norwich area during the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Evidence suggests, however, that only a few of these tradesmen produced formal case furniture. Ebenezer Carew (1745–1801), Huntington’s cousin by marriage, had a shop with five joiners’ workbenches on the Norwichtown Green, virtually next door to Felix. Given their close proximity, they may well have been frequent collaborators. Ebenezer Tracy had unfinished case furniture and a large inventory of cabinet woods, including mahogany and cherry, in his probate inventory (see fig. 4). Jesse Birchard (1736–1809) of Bozrah, to whom two high chests are tentatively attributed, is another likely candidate (fig. 5). Both Tracy and Birchard appear to have produced stylish, distinctive furniture of high quality that can be differentiated from the output of Huntington’s shop. As yet unidentified is the Lebanon or Norwich craftsman responsible for creating a group of highly distinctive furniture for the Trumbull family (fig. 6).[4]

A dozen related case pieces with ownership histories in and around Norwich can now be attributed to the shop of Felix Huntington. These include four chests of drawers, two blockfront desks with shell-carved fallboards, two chest-on-chests, a desk-and-bookcase, and a clock case. Many of these objects have a documented connection to the Huntington family. A group of chairs with similar associations is also discussed here.[5]

Felix Huntington was uniquely fortunate to have been born into one of the colony’s most powerful, affluent, and influential families. His relatives included three Revolutionary War generals, a president of the Continental Congress who later became the state’s governor, several ministers, judges, merchants, and an array of skilled tradesmen. He spent his entire life in a town where he had easy access to goods from Europe and the West Indies, including high-quality mahogany, exotic woods, imported leather, and other luxury items.

Born in Norwich on November 28, 1749, Felix was the fourth of five children and third son of Daniel (1711–1753) and Rebecca Huntington (1726–1798). The younger Huntington’s maternal grandmother, Rebecca Lathrop (1695–1774), was the sister of Norwich joiner William Lathrop (1688–1778), in whose shop Felix probably trained. There is no evidence that Daniel Huntington was a joiner, and he died when Felix was three years of age. In 1773 Felix married Anna Perkins (1756–1806), whose maternal grandfather, James Brown (ca. 1700–1765), came from Newport; however, no family connection to a major cabinet shop there has been established. None of the couple’s three sons was trained in their father’s craft, perhaps a result of the financial difficulties he encountered when they were still young.[6]

Felix lived and worked in the “old” part of town, now known as Norwichtown. When he completed his apprenticeship in 1771, he purchased the land for his first shop from his great-uncle Ebenezer Lathrop, brother of William. In 1791 Huntington was forced to sell his home and shop to settle his debts. Four years later, he built a new shop nearby, next door to pewterer Samuel Danforth (1770–1827). In 1800 Felix bought a house across the street, owned by his cousin Ebenezer Carew, in whose joiner’s shop he probably worked during the years he did not have a business of his own.[7]

In a number of primary and early secondary sources, Huntington is variously identified as a cabinetmaker, joiner, and carpenter. His only trade advertisement, placed in 1778, requested “A QUANTITY of Hogs Bristles,” presumably for use in brushes. The most enlightening document pertaining to his career is an October 1792 petition from Huntington to the State General Assembly:

Shewing to this Assembly that for some Years before the late War [Felix Huntington] . . . carried on the Business of Cabinet making in said Norwich until the Commencement of the War when the Custom of said Huntington failing in Order to vend more of his Work he build a Vessell and fitted her for Sea and likewise purchased several Shares in sundry other Vessels and that by sundry heavy losses by Sea in the Course of the War at the Time when Peace took Place he was indebted to sundry Persons about fifteen Hundred Pounds in the whole that for the Term of nine Years he hath strove to the utmost of his Power to struggle through his embarrassment and extricate himself from Debt, and that there still remains due from him about One thousand Pounds lawful Money, that he finds himself in the decline of Life hath a large Family of small Children to support by his Labour and that he is unable to pay all his Just Debts Praying for an Act of Insolvency in his favour as per Petition on file, and no one of the said Creditors appearing to object they having been duely Notified.

His petition was granted with the provisions that he deliver “all his Estate and Effects for the Use of his Creditors in proportion to their respective Debts and demands excepting only one Cow, and such necessary wearing Apparel for himself and Family, and such Household furniture and Tools of his Trade as are exempted by Law.”[8]

In July 1792 tax collector Ebenezer Bushnell placed an ad for the sale of Felix’s real estate to pay back taxes for 1790 and 1791. In May 1794, presumably fulfilling his role as one of the bankruptcy commissioners, merchant Andrew Huntington advertised for sale at his store: “For the benefit of the Creditors of Felix Huntington . . . An Easy Chair, a large Table, Mahogany Clock Case, a dozen silver handle Knives and Forks, a Shagreen Case, a pair brass Candlesticks, a parcel of Ivory, and sundry other Articles.” In addition to selling some of his own possessions, Felix attempted to satisfy some of his creditors with cabinetwork. A surviving promissory note reads: “In Value Recd I promise to pay Gurdon Bill Twelve dollars & twenty eight Cents on demand to be taken in Cabinet work if delid when called for in a reasonable time if not Cash with Interest untill paid. Norwich December 6, 1798 Felix Huntington.”[9]

Census records also provide a glimpse into Huntington’s troubled finances and their impact on his productivity. In 1790 his household included four males over the age of sixteen (presumably apprentices and/or journeymen) in addition to his family, but in 1800 and 1810 there were none. Also noteworthy is his omission from town tax assessments by trade in 1797 and 1798. These documents, covering the years 1795 to 1798, identify individuals by name and occupation for each town in the state. The lists are incomplete, and identification of trades varies. Of the two surviving Norwich lists, the one for 1797 identifies all craftsmen as “mechanics.”[10]

In 1815, at age sixty-five, Huntington advertised his house and shop for sale. Five years later the census recorded him living with his son Felix Augustus. Although the elder Huntington’s headstone in the Norwichtown Burying Ground and most subsequent publications record his death as having taken place in September 1822, the Norwich Courier and other newspapers reported it as September 3, 1823.[11]

Furniture from the Shop of Felix Huntington

Like most eighteenth-century Connecticut craftsmen, Felix Huntington did not sign or label his work. All attributions to his shop are based on circumstantial evidence, which includes histories of ownership, account book entries, correspondence, probate inventories, shipping records, and similarity to documented objects. Also assumed is that Huntington family members and business associates would have given more patronage to him than to other local cabinetmakers. This theory is supported by a letter, dated July 4, 1782, from John Chester of Wethersfield to his brother-in-law Joshua Huntington (a second cousin of Felix) in which he orders seating furniture but takes issue with the cost of case furniture: “The Chairs we will have . . . [but Felix] Huntington has rather raised the price of Bureaus. I understood [from] you he asked £7 for one swell’d and trimmed. £6 is certainly higher for a plain one without trimmings. You shall hear more from me soon on this business.” A second letter written eight months later included Felix’s bill, presumably with payment for the chairs, but, regrettably, the invoice has not survived.[12]

Huntington’s furniture production can be divided into two periods, separated by his bankruptcy and the sale of his shop in 1791. Compared with the work of some contemporaries, the number of case pieces associated with his shop is relatively small. Huntington’s most productive years, and those yielding the majority of his best work, are the 1770s and 1780s, a prosperous time for Norwich as well as for members of his extended family. Evidence confirms that Huntington continued making furniture during the federal period, but the quality and quantity of his work appear to have declined. Although he maintained a shop until at least 1815, little documented furniture made after 1800 is known.[13]

Several design and construction features differentiate the products of Huntington’s shop from furniture made by other makers. His work reflects a strong Rhode Island influence and encompasses a variety of sophisticated case and seating forms with a preference for certain details including enclosed ogee heads without rosettes; four-drawer lower cases; serpentine façades; canted corners with stop-fluting and lamb’s-tongue terminals (figs. 20, 24); proficiently carved shells; cock-beaded drawer fonts; ogee and straight bracket feet with paired horizontal cusps (figs. 11, 18); and, on later work, straight bracket feet with canted corners and a conventional vertical cusp (figs. 13, 14). His chair designs feature interlacing splats, most often of the so-called “owl’s-eye” variety, prominent crest ears, and over-the-rail upholstered frames (figs. 25-27). Much of Huntington’s formal furniture is made of mahogany and mahogany veneer; cherry is more common in his later work. Secondary woods used in his shop include white pine, tulip poplar, maple, chestnut, and, occasionally, butternut. As was the case in most cabinet shops, Huntington and his workmen used patterns, design formulas, and standardized construction and assembly techniques. In Huntington’s case, construction and assembly practices appear to have been enforced less rigorously than in shops managed by some of his contemporaries. Although this makes some attributions problematic (figs. 12-14), several structural details recur in furniture associated with him: backboards are oriented horizontally and nailed into rabbets; drawer dividers are blind-dovetailed at the sides and covered with facing strips at the front; drawer runners are set in dadoes in case sides in earlier case pieces and nailed in later work; wooden pins are often used as fasteners (fig. 21); feet are reinforced with small triangular blocks (fig. 16); the bottoms of drawers are dadoed to the sides and front; drawer sides are rounded at the top in early work but not on later case works; and cutouts for hardware are rounded and chamfered on serpentine and blocked drawer fronts (fig. 19). Variations in the construction of Huntington’s furniture probably reflect shortcuts owing to economic shifts and the individual work habits of journeymen and/or collaborators. It is also possible that he subcontracted specialized work like carving, since the shells on his furniture differ significantly from piece to piece. With the exceptions of Ebenezer Carew and a possible apprentice named Nathan Clark (1766–1839), Huntington’s workmen remain unidentified.[14]

The most elaborate and securely documented object attributed to Huntington’s shop is a mahogany blockfront desk originally owned by his second cousin, Revolutionary War hero Major General Ebenezer Huntington (figs. 2, 3). The desk remained in Ebenezer’s family home for more than a century until the death of the last of three unmarried daughters in 1885. New London collector George Smith Palmer (1855–1934) bought the desk from Huntington heirs and subsequently sold it, along with other objects, to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1918. Thirty years later the museum transferred the desk to the Art Institute of Chicago.[15]

Although the Ebenezer Huntington desk has Rhode Island–inspired details like a shell-carved fallboard, its double-cusped ogee feet set it apart from Rhode Island work. Elaborately scrolled feet and aprons have long been associated with southeastern Connecticut furniture, but the design of Huntington’s foot is so idiosyncratic that it can be considered diagnostic of his shop’s work. As the feet on the desk reveal, his ogee model is distinguished by having rounded blocking that conforms both to the façade and the outer edge of the foot, paired cusps oriented horizontally and scrolled upward at the inner edge, and a prominent bead at the inner edge with a wider bead, or astragal, at the base (see fig. 11).

Huntington’s desk is unique in its use of zebrawood (Goncalo alves)—a dark-figured exotic probably imported from Brazil—for the interior drawer fronts (fig. 3). Although there is no reason to assume that this was not intentional, exotics occasionally entered the mahogany trade inadvertently, as evidenced by the occasional use of corbaril (an extremely hard wood that is very difficult to cut) in early Boston furniture. Unlike corbaril, zebrawood would have provided a contrast in color and figure to the mahogany used elsewhere as primary wood on the desk.[16]

A nearly identical desk also has strong family connections to Norwich, but the identity of its first owner is uncertain (figs. 7-11). Its principal difference lies in the simpler interior, which is flat rather than serpentine in configuration; the shell on its prospect door likewise has straight rather than serpentine lobes (fig. 8). Compared with the flamboyant amphitheater-style interiors of contemporary desks attributed to nearby Colchester shops, both Huntington interiors are surprisingly restrained.[17]

A desk-and-bookcase originally owned by Windham merchant Judge Ebenezer Devotion Jr. (1740–1829), another of Felix Huntington’s second cousins, is relatively austere when compared with the preceding desks (fig. 12). The former object is identified in Devotion’s will as “My Mahogany Desk & Bookcase [with] all my Library of Books and Manuscripts.” His account book records numerous transactions with Felix Huntington over a twenty-year period beginning in 1779 that included purchases of a mahogany bureau, a half dozen chairs, a “large” table, a cherry “Pembroke” table, a pair of “backgamd” (backgammon) tables, and two sideboards, one cherry, the other mahogany. Huntington also settled a large account balance of £15.4 in 1798, presumably with furniture.[18]

The construction of the lower section of the Devotion desk-and-bookcase matches that of the blockfront desks, but the former object displays a number of cost-cutting features. The feet are simplified versions of those on the blockfront desks (figs. 2, 7), and the writing compartment has a single row of drawers surmounted by pigeonholes with simple ogee-shaped valences. With a central vertical divider cut to allow access to a latch for the doors and two rows of fixed shelves, the interior of the bookcase section is also quite plain.

Judging from surviving examples, chests of drawers, or bureaus, appear to have been a mainstay of the Huntington shop. The most common model features a serpentine façade, canted corners and either cusped ogee or plain bracket feet (figs. 13-16). A cherry bureau that descended in the same line as the Devotion desk-and-bookcase displays the neat, precise construction associated with Huntington’s earlier work, although the feet and nailed drawer runners suggest that the piece was made after 1785. Most of the bracket foot examples probably postdate Felix’s bankruptcy in 1792. The chest illustrated in figure 14 supports that theory, having stamped federal brasses and a number of cost-saving structural shortcuts: the edge of the top is beaded rather than molded; the rear foot bracket is angled rather than being ogee-shaped; and the base molding is a simple cove without a fillet at the top and bottom. This chest could represent the work of an apprentice or journeyman from Huntington’s shop.[19]

The mahogany chest-on-chest illustrated in figures 17–21 has a relatively low arching pediment with no scroll terminations, a design likely influenced by Newport furniture. The roof boards are lined on the interior with pages from the June 10, 1784, issue of the Norwich Packet. More unusual is the pitched pediment of the chest-on-chest illustrated in figure 22. The somewhat awkwardly conceived upper case suggests that Huntington’s shop was unaccustomed to producing this particular form. The center plinth, with its virtually straight sides, and the unusual wide-lobed shell differ significantly from those on the bonnet-top example. The pitch-pediment chest-on-chest also has a curious labor-saving feature; the lower case drawer locks are attached above the right brasses, where the drawer front is thinner than in the middle. This eliminated the need for a deep lock mortise, which would have been required for the more conventional placement of locks at the top center of each drawer.[20]

The account books of Norwich clockmakers Joseph Carpenter (1747–1804) and Nathaniel Shipman (1764–1853) record several transactions with Felix Huntington, including the purchase of at least five clock cases each between 1787 and 1790. In 1789 Huntington’s cases in mahogany sold for £5 and cases in cherry, £3. The clock illustrated in figure 23 descended in the family of Felix’s older brother, Levi (1747–1802), a Norwich merchant and frequent collaborator in the cabinetmaker’s business ventures. It was listed in Levi’s probate inventory as “1 Brass Clock 200 / [£10].” The silvered brass dial is inscribed “Shipman / Norwich” and elaborately engraved in the manner of Norwich’s senior clockmaker, Thomas Harland (ca. 1735–1807), Shipman’s presumed master. The arched door at the waist has a complex applied molding and is flanked by chamfered stop-fluted corners with lamb’s-tongue ends, comparable to those of the chest-on-chest (figs. 20, 24).[21]

Several sets of side chairs have been attributed to the Huntington shop based on family ownership (figs. 25, 26). As with his case furniture, the formal chairs are made of either mahogany or cherry. Distinguishing characteristics include knee brackets attached to the front seat rail and legs, and crests with prominent ears, some having spiral carving (fig. 28). Furniture scholar Robert F. Trent has suggested that much of the upholstery was the work of Felix’s cousin Jonathan Huntington Jr. (1751–after 1792).[22]

Partial provenances for the two sets of mahogany side chairs mentioned above and an easy chair (fig. 29) are recorded on early twentieth-century copper plaques: “This chair was in the Jabez Huntington House, 16 Huntington Lane, Norwich Town, Conn. Bought by Edith Huntington Wilson in 1922. This chair left to her cousin Sydney (Stevens) Williston in 1939.” Major General Jabez Huntington (1719–1786), patriarch of the Revolutionary War–era Huntington clan, owned the house now known as the Bradford-Huntington House. His life and marriage dates suggest that the chairs were commissioned by one of his children, most likely his son, Major General Zachariah Huntington (1764–1850), another of Felix’s second cousins. The house was purchased from his descendants in 1922 by antiquarian Edith St. George (Huntington) Wilson (1866–1939), a distant relative.[23]

One of the aforementioned sets has over-the-rail upholstery and distinctive owl’s-eye splats—a design long associated with the Norwich area (fig. 25). These splats differ from those on similar chairs produced in Massachusetts in that their large circular piercings (“eyes”) are positioned much higher. Nail holes on the underside of the front seat rail and inner edges

of the front legs indicate that these chairs originally had knee brackets. The other set has slip seats, uncarved ears, and more complex strapwork (fig. 26).[24]

Many other side chairs have been attributed to the Huntington shop based on their similarity to the examples with commemorative plaques. One mahogany chair with a slip seat and uncarved ears reputedly descended in the family of an unidentified Huntington descendant. Another pair from a cherry set, possibly dating from 1782, descended in the Devotion family with the chest of drawers and desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 12 and 14.[25]

The most elaborate set of side chairs attributed to Huntington’s shop have embossed, gilt “Spanish” leather upholstery attached over the rail with oval brass nails (fig. 27). Identical leather was used to cover walls in an unidentified Norwich house and a trunk lined with an 1805 Norwich newspaper. Advertisements listing imported nests of gilt leather trunks, presumably of different sizes, appeared in New London County by 1763. Decorated leather and leather goods of this type were popular in Europe in the mid-eighteenth century. Much of this leather was produced in the Netherlands and imported to the colonies from England.[26]

Robert Trent has attributed simpler joined chairs with upholstered seats, such as those with cross slats, to the Huntington shop. Although these objects have ears, crest rails, and knee brackets similar to those on the chairs illustrated in figures 25 and 26, they lack secure documentation and have details that differ from seating in the Huntington group. Many of these divergent chairs were likely produced in other shops, especially that of Ebenezer Tracy, the region’s most prolific chairmaker.[27]

Huntington’s shop did, however, produce a range of less expensive turned and painted chairs. In 1789 he delivered “writing chairs” valued at 20s. each, three dozen green Windsors, and an easy chair to the brig Polly, scheduled to debark for the West Indies. Governor Samuel Huntington (1731–1796) of Windham, another of Felix’s second cousins, owned “7 Green Armed chairs” valued at £2.6 and “5 High top’d green Chairs” (probably Windsors) valued at 10s.[28]

Ledgers and account books, including those of merchant Andrew Huntington, clockmaker Nathaniel Shipman, and Judge Ebenezer Devotion, confirm that Huntington’s shop produced an array of household furnishings. Among the objects listed are various types of tables and stands, looking glasses, sideboards, firescreens, and pitchpipes. Future research will undoubtedly identify some of the objects and possibly other work associated with Huntington.[29]

Some of the apprentices and journeyman who worked in Huntington’s shop may have established cabinetmaking businesses of their own (see checklist). A desk with structural and stylistic features associated with his work has a plaque inscribed with the following provenance: “From the Maker Nathan Clark To Ruth Parker Married Dec. 10th 1793 To Olive Clark Durkee March 25th 1822 To Eliza Durkee Gifford May 13th 1840 To Herbert Morton Gifford Oct. 17th 1877 To Paul Morton Gifford Sept. 13th 1911.” Nathan Clark (1766–1839) of Mansfield, the presumed maker of the desk, apparently presented it as a wedding gift to his wife, Ruth Parker (1765–after 1850). The dates on the plaque suggest that it passed from generation to generation at the date of the recipient offspring’s marriage.[30]

The Clark desk exhibits most of the index characteristics of the Huntington shop’s case furniture (use of mahogany and mahogany veneer, dadoed drawer supports, cock-beading on exterior drawers, double-cusp feet with small triangular blocks, strips covering drawer blade dovetails), but its execution is less refined. The use of maple for the drawer dividers and vertically laminated feet (mahogany on pine) are also atypical of Huntington’s work. Variations of this type are common in the work of apprentices and journeymen who developed work habits in one shop and subsequently modified or augmented them to expedite production, take advantage of locally available materials, or accommodate consumer expectations.

Little is known about Clark other than his Revolutionary War pension file, which states that he spent his adult life in Mansfield, about twenty miles northwest of Norwich in Windham County. There is no record of him as a cabinetmaker, nor does he appear as a woodworker in the surviving Mansfield tax assessments for 1795 and 1797. Although there is no reason to doubt the plaque’s assertion that Clark made the desk, one must acknowledge the possibility that he either bought or inherited the piece and that subsequent family tradition was in error. The latter seems unlikely, however, since a desk of this caliber would have been an unlikely purchase for a young man who, at the very least, subsidized his income by farming.[31]

The objects described above constitute the largest and most cohesive group of furniture attributable to a single shop in southeastern Connecticut. Their association with Norwich and the Huntington family combined with the documentary evidence surrounding the life and career of Felix Huntington are persuasive in identifying him as the shop master. The pervasive influence of Newport design, especially in the blockfront examples, is readily apparent, as are regional idiosyncrasies evident in the bold ogee feet, embellished canted case corners, and elaborate strapwork chair backs. These designs, for the most part, lack the imaginative flair of Samuel Loomis III (1748–1814) and other nearby Colchester contemporaries but remain in keeping with the fashion of the day. Nevertheless, Huntington’s craftsmanship is meticulous and his decorative vocabulary impressive for the context in which he worked. He deserves to be included in the first rank of Connecticut’s eighteenth-century cabinetmakers.[32]

Checklist

Furniture Craftsmen Working in Norwich, 1770–1800[33]

ALLYN, STEPHEN BILLINGS (1774–1822), advertised with DANIEL HUNTINGTON 3D from the Chelsea section of Norwich in 1797, that they “carry on the Cabinet and Chair making business . . . [and] doubt not but that they shall be able to exhibit as good work, and as cheap as can be had from New-York or elsewhere.” The partnership dissolved by 1802, when Huntington advertised alone. In 1807 Allyn advertised that he had moved his shop to his dwelling house. In 1810 he advertised with JOEL HYDE (1764–1853) of Preston “FOR SALE, A FEW THOUSAND FEET CHERRY BOARDS.” In 1821 Allyn announced his departure for the West Indies; he died in Demerara, British Guiana, the following year. His probate inventory included five workbenches, a lathe, many tools, and a considerable quantity of lumber, including cherry and mahogany boards. The implication is strong that he was a major furniture producer during the federal period.[34]

AVERY, JABEZ (1733–1779), his son RICHARD (1764–1824), and his father, JOHN (1706–1766), all owned joiners’ tools. Jabez’s inventory indicates he was also a turner, and an Avery genealogy describes him as a coach maker. Jabez was the uncle of joiners AMOS and JOHN GAGER.[35]

AVERY, OLIVER (1757–1842), a first cousin of clockmaker John Avery, was born across the Thames River in Preston. He was living in Norwich at the time of the Revolution. In 1781 he advertised as a “CABINET AND CHAIR MAKER, Near the Court House, Norwich . . . [where] he carries on said business in all its various branches.” Shortly thereafter he moved to Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where he appeared in the 1790 census. In 1799 he moved to (North) Stonington, Connecticut, where his house still stands. Oliver’s account books (1788–1831) and other papers are at the Winterthur Museum. These papers document his production of several furniture forms, including clock cases.[36]

AYER, JOSEPH (1733–1793), lived in Franklin. His probate inventory includes a shop, bench, lathe, and a large assortment of woodworking tools.

BACKUS, JOHN (1740–1814), was a lifelong resident of Norwich. His probate inventory lists “Joiner’s & Turner’s Tools @ $120” and “Lumber & Stock in the Shop, Barn &c, unfinished @ $20.” Also listed are a number of finished and unfinished wheels of various sizes and reels, implying that he made spinning wheels. John had tools bequeathed to him by his brother SIMON (1729–1764), whose inventory indicates that he also had a brief career as a Norwich joiner.

BIRCHARD, JESSE (1736–1809), lived in Bozrah and married the widow of Norwich chairmaker OZIAS BACKUS (1739–1764). A few weeks before his death Birchard advertised “FOR SALE . . . a small BARN and SHOP for the Cabinet and Chair Making business.” The 1790 census lists four adult males and one under sixteen in his household, implying that he may have had one or more apprentices and/or journeymen. Birchard’s inventory lists a bench, lathe, and woodworking tools. Two similar mahogany scroll-top high chests have been attributed to him, based on ownership by descendants and attachment of his Revolutionary War pass to the side of a drawer (fig. 5).[37]

BRANCH, STEPHEN (1744–1828), was in born in Preston. Circa 1790 he moved eight miles north to Lisbon, where he built a house that stands today. Branch’s inventory lists a large assortment of joiner’s tools and a lathe. His father was Preston joiner THOMAS BRANCH (1698–1778).

BRIGDEN, TIMOTHY (1749–1813), was born in Wethersfield into a family of chairmakers that included his father, THOMAS (1703–1781), and brother MICHAEL (1743–1828). He moved to Norwich shortly after completing his training, circa 1770. In addition to the customary assortment of tools, his inventory lists a separate “Bench Shop” and “Turning Shop” as well as a “Man’d” and “Water Lathe.” His lumber supply included planks of butternut.

CAREW, EBENEZER (1745–1801), a lifelong resident of Norwich, was closely related through his mother and by marriage to numerous HUNTINGTON and LATHROP craftsmen. He sold the house he had built on the Norwichtown green to FELIX HUNTINGTON in 1800. In 1778 he advertised for an apprentice in “the joiner’s business,” and for a runaway apprentice in 1791, at which time he described himself as a “House Carpenter & Joiner.” The 1790 census lists seven males over the age of sixteen in his household, all but two of whom may have been apprentices and/or journeymen. Town tax assessments for 1797 describe him as a “mechanic” with a relatively high assessment of $25. His probate inventory is extensive and includes “5 Joiners Work benches . . . 1 Turning Lathe . . . 1 Duff Tail [Saw] . . . etc.” The tools and lumber make it clear that he was both a house and a shop joiner, and, perhaps, the busiest joiner in town.[38]

CASE, SAMUEL (1762–1791) and his brother ASAHEL (1769–1828) both owned joiner’s tools. Samuel owned a lathe and unfinished table legs, window frames, and clapboards, indicating he was both a house and a shop joiner. Asahel owned a box of rush, suggesting he may have made chairs.

DOWNER, JABEZ (1749–1791), was a resident of Franklin. His inventory includes tools and a lathe, as well as unfinished chair, table, and bedstead parts, and wheel spokes for carts. He also owned a large quantity of cherry, maple, pine, oak, and ash lumber. No case furniture is mentioned, even among his limited personal belongings.

FARGO, JASON (1735–1782), owned, in addition to the customary tools and a lathe, “1 Set for a Stand Leg” and “Part of a Set furniture for draws.”

GAGER, AMOS (1772–1809), and his older brother JOHN (1764–1817) worked in Franklin. Amos had the more comprehensive inventory with unfinished bedstead, table, chair, and wagon parts as well as large quantities of chestnut, oak, and ash. He had two benches and a lathe. A flat-top maple high chest that descended in the family is privately owned, but its maker is unidentified.[39]

GRIST(E), JOHN (1734–1832), a cousin of JESSE BIRCHARD and nephew by marriage of WILLIAM LATHROP, is said to have sold his joiner’s shop in 1783 before moving to Pennsylvania five years later. The Griste genealogy reports that he apprenticed as a cabinetmaker at age fourteen.[40]

HUNTINGTON, DANIEL, 3D (1776–1805), a cousin once removed and likely apprentice of FELIX HUNTINGTON and brother of Norwich silversmith Philip Huntington, advertised when he completed his apprenticeship in 1797 with STEPHEN BILLINGS ALLYN as quoted above. In 1802 he advertised alone for “A JOURNEYMAN Cabinet Maker.” There is no probate inventory on file.[41]

HUNTINGTON, FELIX (1749–1823): See article.

KELLEY, HEZEKIAH (1761–1822), advertised in 1793 the dissolution of a cabinetmaker partnership with DAVID HAMILTON (1766–1798) who is otherwise unknown as a woodworker. The same year Kelley made seven clock cases for Daniel Burnap of East Windsor. The four adult males in his 1790 household could have included as many as three apprentices or journeymen. By 1795 he had become a merchant, identified as such in 1797 town tax assessments and confirmed with an ad. He invested heavily in the West Indies trade with disastrous results, filing for bankruptcy in 1801. He was still in Norwich in 1813 but died in Illinois. JOHN BACKUS was his wife’s uncle and a likely master.[42]

LATHROP, WILLIAM (1688–1778), was one of a dynasty of Norwich woodworkers that includes his cousin once removed ZEBEDIAH LATHROP (1743–1783) and great-nephew ISAAC LATHROP (1765–1826). He was a likely master to another great-nephew, FELIX HUNTINGTON. An exceptional set of early maple Queen Anne chairs, inscribed in 1756 with the name of his niece Elizabeth Lathrop, has been attributed to him. The account book of Isaac Huntington (1688–1764) records a chest and cradle made by Lathrop in 1720. His probate inventory (at age ninety) lists only a few household tools. Zebediah’s inventory contains a full complement of joiner’s tools and barrel parts. Isaac advertised as a shop joiner in 1788 but was living in Rome, New York, by 1798.[43]

LESTER, TIMOTHY (ca. 1769–1810), advertised first in 1791 in a partnership with ELEAZER HAZEN (1772–1849) as “Lester & Hazen, CABINET & CHAIR-MAKERS . . . [who] supplied every kind of FURNITURE that can be comprehended in their line of business . . . by practicing with some of the best workmen on the Continent.” The partnership was dissolved a year later, and Lester continued to advertise alone intermittently until 1799, including requests for apprentices. The 1800 census suggests he may have had an apprentice at the time. In 1802–1803 he was engaged as a “machinist” to assist in the building of a hemp-spinning mill. His inventory, in addition to three benches and mahogany, maple, and cherry boards, has unfinished furniture that includes a stand and washstand. Among his tools is a “vaniering saw.” Clapboards, window frames, and other materials for house joinery are present as well.[44]

TIFFANY, ISAIAH, JR. (ca. 1723–1806), was born in Woodstock and moved with his family to Lebanon in 1743. Ten years later he moved to Norwich, where he remained for about twenty years before returning to Lebanon. His account book, covering the years 1746–1772, demonstrates the versatility of his talents and occupations. Early in his career he produced a substantial quantity of seating and case furniture, including nine high chests, three desks, and three clock cases, as well as many chairs and tables. Many of these date before his move to Norwich, where he advertised as a merchant of imported goods in 1768. None of his cabinetwork has been identified with certainty.[45]

TRACY, EBENEZER (1744–1803), known primarily for his Windsor chairs, also produced a full range of other furniture. Working in Lisbon, Ebenezer and his son ELIJAH (1766–1807) are the only two woodworkers in this checklist specifically identified as cabinetmakers in town tax assessments. In 1796 Ebenezer received the unusually high assessment of $80, the highest of anyone in town; his son was assessed the more customary $17. Elijah advertised in 1796 for an apprentice “to the Cabinet and Windsor Chair making business.” A Newport-influenced cherry bonnet-top chest-on-chest, inscribed “Lisbon / 1796,” is almost certainly from Ebenezer’s shop (fig. 4). The 1800 census indicates that he had seven males under the age of twenty-five in his household at the time, four of whom were family members. Preston clockmaker JOHN AVERY (1755–1815) made seven lathes for the shop between 1792 and 1800, along with brass furniture escutcheons, brands, and other items. The number of tools, unfinished chairs and case furniture (including a sideboard and large stock of brasses and locks), board feet of mahogany, cherry, birch, beech, mangrove, chestnut, and other lumber dwarf comparable amounts in other probate inventories. The 2,148 board feet of cherry suggest that the shop produced a significant amount of case furniture in addition to chairs. The presence of mangrove, a tropical wood most often used in ship building, may be unique in a Connecticut cabinetmaker inventory. The shop was sold by family members in 1810 to Preston joiner JOEL HYDE (1764–1853). Furniture scholar Nancy Evans has reviewed his life, work, extended family of craftsmen, and influence in great detail.[46]

WILLIAMS, MOSES (1724–1803), spent most of his working life in Norwich; he moved to Preston after 1788. Even as he approached eighty, Williams appears to have been a busy chairmaker; his probate inventory included “400 chair rounds, 4 Great Chairs finished, 3 do. Unfinished, 440 feet Maple Boards [and] 1 Joyners Shop with all the Tools & Stuff Contained therein.” The shop and tools were valued separately from his house and land at $200.00—more than all of his personal belongings put together.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author thanks furniture scholar and conservator Robert Lionetti for his long-standing collaboration and support and for corroborating much of the technical detail in this article.

Henry W. Kent and Florence N. Levy, The Hudson-Fulton Celebration, 2 vols. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1909), 1: 68, no. 169. Luke Vincent Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America, 2 vols., 2nd ed. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1913), 1: 92. Joshua Read (1725–1795) left Norwich for Windsor, Massachusetts, where his son Simon was born in 1763. There is no other record of him as a cabinetmaker. The Read high chest is illustrated in Houghton Bulkeley, “The Norwich Cabinetmakers,” Connecticut Historical Society Bulletin 29, no. 3 (July 1964): fig. 1. It is highly unusual in having a mirror, reportedly original, between pairs of upper-case small drawers. Ada R. Chase, “Ebenezer Tracy, Connecticut Chairmaker,” Antiques 30, no. 6 (December 1936): 166–69; Chase, “Amos D. Allen, Connecticut Cabinetmaker,” Antiques 69, no. 2 (August 1956): 146–47; Chase, “Two 18th-Century Craftsmen of Norwich,” Connecticut Historical Society Bulletin 25, no. 3 (July 1960): 84–88; Chase, “Joseph A. Carpenter, Jr., Silversmith and Clockmaker,” Antiques 85, no. 6 (June 1964): 695–97; and Chase, “Thomas Harland’s Clock—Whose Case,” Antiques 87, no. 6 (June 1965): 700–701. Bulkeley, “The Norwich Cabinetmakers,” pp. 76–85.

Craftsmen & Artists of Norwich, edited by Jo Darmstadt (Stonington, Conn.: Pequot Press, 1965), pp. 50–60 with addenda. The catalogue includes an expanded list of Norwich cabinetmakers by Houghton Bulkeley (pp. 1–11). The chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 4 (cat. 29) is inscribed as made in Lisbon; John Backus was a lifelong resident of Norwich. His probate inventory indicates that he was a wheelmaker (see checklist).

Minor Myers Jr. and Edgar deN. Mayhew, New London County Furniture, 1640–1840 (New London, Conn.: Lyman Allyn Museum, 1974). The chest-on-chest inscribed “Lisbon / 1796” on the inside of the backboard is no. 70. Town tax assessments by trade for the years 1795–1798 for each town in Connecticut are in the William L. Warren Collection, Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, Conn. (hereafter CHS). Ebenezer Tracy and his son Elijah are the only cabinetmakers listed in Lisbon’s 1796 assessments (see checklist). Ebenezer’s assessment was by far the highest of anyone in town. Robert F. Trent and Nancy L. Nelson, “New London County Joined Chairs,” Connecticut Historical Society Bulletin 50, no. 4 (Fall 1985): 1–200. Thomas P. Kugelman and Alice K. Kugelman with Robert Lionetti, Connecticut Valley Furniture: Eliphalet Chapin and His Contemporaries, 1750–1800 (Hartford: Connecticut Historical Society, 2005), pp. 201–83. For much of the eighteenth century Colchester was part of Hartford County, with economic and social ties to Hartford, Middletown, and other valley towns.

Ebenezer Carew’s mother and wife were both Huntingtons. His brother-in-law Jonathan Huntington Jr. (1751–after 1792) is believed by Robert Trent (“New London County Joined Chairs,” p. 23 and n22) to have been Felix’s principal upholsterer. Carew’s ads and probate inventory indicate he was both a house and a shop joiner (see checklist). For details of Ebenezer Tracy’s probate inventory, see checklist. For illustrations of the Birchard high chests, see Antiques 131, no. 1 (January 1987): 4; and Wallace Nutting, Furniture Treasury, 3 vols. (New York: Macmillan Co., 1928), 1: fig. 375. Birchard’s Revolutionary War pass is glued to a drawer side of the high chest that descended in a branch of his family (fig. 5). The Nutting example, formerly in the George S. Palmer Collection, has full twisted columns at the upper case corners similar to those associated with high chests attributed to the neighboring town of Preston. The attribution to Birchard’s shop was part of a presentation by the author at the Winterthur Furniture Forum in 2009. The Trumbull family furniture included a shell-carved, blockfront chest-on-chest with unusual oblong claw-and-ball feet and Corinthian capitals (fig. 6), a marble-top table, and an elaborately carved candlestand. For details, see Nancy E. Richards and Nancy Goyne Evans, New England Furniture at Winterthur: Queen Anne and Chippendale Periods (Winterthur, Del.: Winterthur Museum, 1997), pp. 248–49, 285–86, and William V. Elder and Jayne E. Stokes, American Furniture, 1680–1880, from the Collection of the Baltimore Museum of Art (Baltimore, Md.: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1987), pp. 80–81. The chest-on-chest was last owned by Jonathan George Washington Trumbull (1787–1853), grandson of Jonathan Trumbull Sr. He was related through both his mother and wife to joiners in the Lathrop and Backus families (see checklist).

Nine pieces were examined in the course of this study. Two of the chest of drawers are mahogany, a primary wood rarely used in furniture from this area.

William Lathrop is credited with making a chest and cradle in 1720 in the Isaac Huntington account book, CHS. A set of formal Queen Anne chairs inscribed with the date 1756, by Lathrop’s niece Elizabeth, are attributed to him as well. See also Trent and Nelson, “New London County Joined Chairs,” p. 79 and no. 21; and checklist. William B. Brown, “Chad Browne of Providence, R.I.,” New England Historical and Genealogical Society Register 80, no. 2 (April 1926): 176.

Mary E. Perkins, Old Houses of the Ancient Town of Norwich (Norwich, Conn.: Bulletin Co., 1895), pp. 191–92, 213–14.

Norwich Packet, November 23, 1778. Public Records of the State of Connecticut, edited by Leonard W. Labaree (Hartford: State of Connecticut, 1948), 7: 539–41. Public Records of the State of Connecticut, edited by Leonard W. Labaree (Hartford: State of Connecticut, 1951), 8: 62–63.

Weekly Register (Norwich, Conn.), July 17, 1792; Norwich Packet, May 22, 1794. Felix Huntington promissory note, MS file no. 72896, CHS. Gurdon Bill (1757–1815) was a Norwich sea captain and another of Felix’s second cousins. His brother-in-law Daniel Lathrop Coit (1754–1833) was one of Felix’s two bankruptcy commissioners.

Town Tax Assessments, 1795–1798, Warren Collection, CHS. Ebenezer Carew is listed in 1797 but not in 1798 (see checklist).

Norwich Courier, July 5, 1815. The property apparently did not sell. A follow-up advertisement placed by his son Felix Augustus in 1821 offers the house, shop, and land once again. Hale Cemetery Inscriptions, Connecticut State Library, Hartford (hereafter CSL). Norwich Courier, September 10, 1823. This is confirmed in both the American Mercury and the Connecticut Courant of September 16, 1823, among others. His headstone has either been misread or was carved sometime after his death when memories were faulty. His death is not recorded in town vital records or family genealogies. No probate records survive.

“Huntington Papers: Correspondence of the Brothers Joshua and Jedediah Huntington during the Period of the American Revolution,” in Collections of the Connecticut Historical Society, Vol. 20 (Hartford, 1923), pp. 159–60, 171.

Kugelman, Kugelman, and Lionetti, Connecticut Valley Furniture, p. 133. The authors have identified at least eight high chests from the Eliphalet Chapin shop in East Windsor, a dozen high chests from the Wethersfield Willard group, and eight Higgins group block-and-shell chests from Chatham. The shop master for the last two groups has not been conclusively identified. The account book of Judge Ebenezer Devotion Jr. records the purchase of a mahogany sideboard from Huntington in 1799. Lance Mayer and Gay Myers, The Devotion Family (New London, Conn.: Lyman Allyn Museum, 1993), p. 53.

In general, shops in the Connecticut River valley appear to have enforced standardized work practices more rigorously than in other regions, perhaps because craft traditions were more tightly controlled and based on family ties.

Kent and Levy, The Hudson-Fulton Celebration, 1: 68, no. 69; and Nutting, Furniture Treasury, 1: fig. 629. See also Judith A. Barter, Kimberly Rhodes, and Seth A. Thayer, American Arts at the Art Institute of Chicago (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1998), p. 104 (acc. no. 1948.122).

Zebrawood identified by J. T. Quirk, Center for Wood Anatomy Research, U.S. Forest Products Laboratory, Madison, Wis., March 1, 1976 (Art Institute of Chicago, acc. no. file 1948.122). Also known as tigerwood, zebrawood belongs to the species Astronium and was most often imported from eastern Brazil. Norwich merchants like Ebenezer Huntington were heavily involved in the West Indian trade. The authenticity of the pigeonhole valances of the desk could not be established.

Christie’s, Important American Furniture, Prints, Folk Art, and Decorative Arts, New York, October 12, 2001, lot 134. Possible first owners, based on descent, include John Chester (1749–1809) of Wethersfield, Thomas Coit (1752–1832) of Norwich, or Gustavus Wallbridge (1738–1819) of Norwich and Bennington, Vermont. For the Colchester desks, see Kugelman, Kugelman, and Lionetti, Connecticut Valley Furniture, pp. 209, 222, nos. 93, 99.

Mayer and Myers, The Devotion Family, pp. 52–53. Ebenezer Devotion probate file, CSL. The desk-and-bookcase was bequeathed to an unmarried son and daughter who shared the judge’s personal estate. It descended in the family of their sister, Eunice (Devotion) Waldo (1770–1854), and is still in the Edward Waldo homestead, now owned by the Scotland Historical Society, Scotland, Conn.

Only two of the chests were available for complete inspection (figs. 13, 14). Information on the others is based on photographs and communication with Connecticut antiques dealer and furniture scholar Arthur Liverant. A virtually identical mahogany chest, also examined, was owned by Nathan Liverant and Son and is illustrated in their brochure, Spring 2002. That firm’s files include a number of similar bureaus with both straight and serpentine façades, indicating that the Huntington shop, and probably others in the region, produced comparable examples. Sotheby’s, Important Americana, New York, October 11, 2001, lot 262; Edwin Nadeau Auction, Windsor, Conn., October 20, 2007, lot 75 (fig. 14). Sotheby’s, Important Americana, New York, January 19, 2008, lot 295 (fig. 15). The chest has an unsubstantiated history of ownership in the Hyde family of Norwich. A virtually identical example is illustrated in Antiques 141, no. 2 (February 1992): 269.

The bonnet-top chest-on-chest was purchased from Joe Kindig & Son in 1959. For the pitch-pediment example, see Christie’s, Important American Furniture, Folk Art, Silver, Prints, and Decoys, New York, January 18–19, 2007, lot 620. It has a twentieth-century brass plaque inscribed “Madeleine P. Nichols from Sara J. Pattison / Com. Isaac Hull,” implying ownership by Commodore Isaac Hull (1773–1843), naval hero of the War of 1812 as commander of the USS Constitution. Before his service in the newly formed U.S. Navy, Hull was active in the West Indian trade from Norwich and New London as master and part owner of several ships. The Connecticut Ship Database (Mystic Seaport) lists him as master of the Norwich ship Minerva and schooners Beaver and Olive from 1795 to 1798. Sara J. Pattison has been identified as Sarah Jarvis Dennis (1828–after 1920) who married Elias Pattison of New York. Their granddaughter, Madeleine P. Nichols (b. ca. 1911) of Boston, was the recipient on the plaque. She had no documented connection with the Hull family. However, both the Pattisons and Hull heirs (two nieces) were living in New York City in the latter part of the nineteenth century, and the chest-on-chest could have changed hands at that time. It next appeared in the shop of Ansonia, Connecticut, dealer Harry Arons in 1963 and was subsequently exhibited in the Diplomatic Reception Rooms in Washington, D.C. Historic Deerfield owns a cherry desk-and-bookcase (acc. no. 54.208) with a pitch pediment that has New London County features, including double-scrolled returns on the ogee feet. The combination of chestnut, butternut, tulip poplar, and pine as secondary woods is also associated with that region. The pediment does not extend the full depth of the upper case, and the joinery is unlike that from the Huntington shop.

Chase, “Two 18th-Century Craftsmen,” p. 85; and Chase, “Joseph A. Carpenter, Jr., Silversmith and Clockmaker,” pp. 695–97. The Carpenter account book (private collection) covers the years 1787–1803; Shipman’s account book (Society of the Founders of Norwich) covers the years 1785–1812. Carpenter, a cousin of Felix Huntington by marriage, also supplied Huntington with eight-day brass movements on three other occasions, one as late as 1795, for which the latter presumably made cases. The Shipman clock is in a private collection. It was purchased from a seventh-generation descendant in 1988 (Betty [Huntington] Culhane to owner, January 15, 1988). The first four generations lived in Norwich, ending with Levi’s great-grandson Jedediah Huntington (1837–1885).

Trent and Nelson, “New London County Joined Chairs,” p. 23. Jonathan’s occupation is documented by a bill for upholstering a set of chairs in the account book of the Preston blacksmith Calvin Barstow (1750–1826). Trent hypothesized that Jonathan might have trained in the Boston area, accounting for the fact that some chairs have over-the-rail upholstery, which is rare in New London County seating.

According to Chase, “Two 18th-Century Craftsmen,” p. 85, Zachariah was one of Felix Huntington’s creditors in 1792. Edith Wilson was only distantly related to previous owners of the Bradford-Huntington House; her eighteenth-century Huntington ancestors had moved to Vermont, and she was born in Spencerport, New York. Her cousin Sydney (Stevens) Williston (1880–1944), to whom the chairs were bequeathed, resided in Northampton and Marblehead, Massachusetts. The earliest reference to the chairs outside the family is Israel Sack, Inc., Antiques from Israel Sack Collection 15 (February 1967): no. 946.

For information on the chair illustrated in figure 25, the author thanks Kevin Tulimieri of Nathan Liverant and Son. For antecedents of this splat design, see John T. Kirk, Connecticut Furniture: Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Hartford, Conn.: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1967), no. 233; and Richards and Evans, New England Furniture at Winterthur, p. 59, no. 33. The three surviving examples all descended in branches of the East Hartford family of Governor William Pitkin (1694–1769). Early generations of the Pitkin family were all from the Hartford area. The Hartford-area origin is further supported by a privately owned corner chair of similar design with history of descent in the Talcott family. Whether these earlier chairs were made in Hartford or Norwich remains unknown. The set of chairs represented by figure 26 is illustrated in American Antiques from Israel Sack Collection, 10 vols. (Alexandria, Va.: Highland House, 1970), 2: 375, no. 946. An image was unavailable. One chair from this set is also shown in Kirk, Connecticut Furniture: Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, no. 246. The seat frame is branded “J.A. BELL” (Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, Del., Decorative Arts Photographic Collection [hereafter DAPC], acc. no. 67.490.68.3060). A likely candidate is James Andrews Bell (1816–after 1863), an upholsterer who was born in New Haven and moved with his family to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, before 1825. Local newspapers and census records list him there from 1850 until his enlistment in the Civil War. He could have worked in the Norwich area during the 1830s or 1840s and reupholstered the chairs at that time. An apparently identical chair (fig. 26) with no family history is in the Leffingwell Inn, Norwich (no. 193, gift of Henry LaFontaine). A similar pair made of cherry with over-the-rail upholstery is in the collection of Historic Deerfield (acc. nos. 2039 a, b; Trent and Nelson, “New London County Joined Chairs,” nos. 54, 55). For the wing chair, see Edwin Nadeau Auction, Windsor, Conn., October 11, 2008, lot 50. Lot 60 in the same sale was an upholstered mahogany lolling chair with square back, said also to be from the Jabez Huntington House. The spiral carving at the end of the arms is similar to that on the ears of Huntington shop side chairs.

Christie’s, Property of Marguerite and Arthur Riordan, New York, January 18, 2008, lot 588. For the Devotion chairs, see Mayer and Myers, The Devotion Family, p. 20, fig. 7; these chairs are at the Brookline (Mass.) Historical Society.

An assembled set of seven chairs, two of which retained their original gilt leather upholstery, were owned by Norwalk dealer John Kenneth Byard in 1958 (DAPC 71.70, microfilm roll no. 1652-9A). He sold one of the chairs with original leather to Mystic Seaport, where it was exhibited in the Buckingham House until 1989. It sold at Skinner, Americana Auction, Bolton, Mass., March 31, 1990, lot 205, and was privately owned until acquired by the Lyman Allyn Museum in 1999. Byard’s remaining six chairs were on view at the Cincinnati Art Museum until offered for sale at Northeast Auctions, Americana Auction, Manchester, N.H., August 6, 2006, lot 1738. The one chair in that group with original leather, differing in details of splat design from the others, had been reupholstered (Brock Jobe to Thomas Kugelman, March 2, 1991; and personal inspection, March 13, 2010). Another chair, apparently from the same set, still retaining its original leather and oval tacks, allegedly descended in the family of Ebenezer Hough (1767–1846) of Bozrah until acquired by the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design in 1999 (acc. no. 1999.67). Hough was a farmer; his will directed that his personal estate be sold and the proceeds divided among his children. A search of Norwich probate inventories conducted in 1991 by James Sexton, covering the years 1769–1826, failed to identify any likely owners of gilt leather objects (CHS acc. file 1999.61.0). The wall covering is illustrated in Catherine Lynn, Wallpaper in America (New York: W. W. Norton, 1980), p. 15. The fragment, said to be from the Stephen Gifford House, is owned by the Society of the Founders of Norwich. A number of individuals by that name resided in Norwich; none of them is associated with a historic building. The gilt leather trunk, owned by the Connecticut Historical Society (acc. no. 1999.61.0), has no ownership history; the newspaper lining it, The (Norwich) Courier, dated April 17, 1805, is most likely at least a generation later than the leather covering. On April 6, 1763, The New-London Summary, or, The Weekly Advertiser reported: “Thomas & Benjamin Forsey, HAVE just Imported . . . at their Store in New London, VIZ . . . Nests of hair and gilt leather Trunks.” Embossed leather wall covering was also used in the Branford home of Connecticut Governor Gurdon Saltonstall (1666–1724). For information on the European origin of gilt leather, see John W. Waterer, Spanish Leather (London: Faber & Faber, 1971); this pattern is illustrated on p. 119, pl. 66.

Trent and Nelson, “New London County Joined Chairs,” nos. 57–59.

Nancy Goyne Evans, American Windsor Chairs (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1996), pp. 289, 291, figs. 6–97. The shipment included some case furniture as well. The invoice for the brig Polly is in the Joseph Williams Papers at Mystic Seaport, Mystic, Conn. A Windham native, Samuel Huntington married Martha Devotion (1739–1794), sister of Judge Ebenezer Devotion Jr. The Winterthur chairs are noteworthy in having seats made of butternut, a wood occasionally used by Huntington in case furniture. Evans points out that since the chairs are unmarked they could also be the work of Ebenezer Tracy or another contemporary chairmaker. Samuel Huntington’s probate inventory contains much formal cherry and mahogany furniture, very likely from Huntington’s shop.

Chase, “Two 18th-Century Craftsmen,” p. 85. The ledger of Andrew Huntington (Society of the Founders of Norwich) is quoted but could not be located during a recent inquiry. Chase mistakenly identifies Andrew as Felix’s father. See also Mayer and Myers, The Devotion Family, p. 53.

Dates all refer to weddings. Inheritance was by direct descent to a daughter or son. Paul Morton Gifford died in 1961 in the nearby town of Woodstock. The desk apparently never left eastern Connecticut, probably accounting for its good condition and original hardware.

Tax assessments, Warren Collection, CHS. Simeon Allen (b. ca. 1758) is the only Mansfield cabinetmaker listed (in 1797).

Kugelman, Kugelman, and Lionetti, Connecticut Valley Furniture, pp. 201–55, nos. 104, 105, for the work of Samuel Loomis. Of particular interest is a mahogany blockfront desk with shell-carved lid that relates to the two Huntington desks (see figs. 104b and 104c). In addition to its distinctively carved shells, it has full spiral columns at the corners that swell in the middle.

Earlier compilations include checklists in Myers and Mayhew, New London County Furniture, pp. 106–32; and Houghton Bulkeley, “The Cabinetmakers,” in Darmstadt, ed. Craftsmen & Artists of Norwich, pp. 1–12. Craftsmen working in Bozrah, Franklin, and Lisbon, which were within the boundaries of Norwich until incorporated as separate towns in 1786, are included. Those identified as house joiners exclusively and transients who died young or moved away are omitted. Probate inventories are on file alphabetically at the CSL. Most are in the Norwich Probate District.

Courier (Norwich, Conn.), May 31, 1797; April 29, 1807; July 25, 1810; January 10, 1821. Joel Hyde worked as a cabinetmaker in Lisbon after 1810.

Elroy M. Avery and Catherine Avery, 2 vols. The Groton Avery Clan (Cleveland, 1912), 1: 326.

Ibid., 1: 283. Norwich Packet, January 23, 1781. Winterthur acc. no. 55x26 (Mic.102).

Courier, June 14, 1809. For illustrations of the two high chests, see Antiques nt. 4 above.

Norwich Packet, July 20, 1778; December 1, 1791. Tax assessments by trade for the years 1795–1798 are in the Warren Collection, CHS. Not all towns are represented for each year, and the trade designations vary from town to town. Many towns simply refer to manual tradesmen as mechanics. Norwich, Bozrah, Franklin, and Lisbon are all represented by at least one such list. Carew and the Tracys are the only individuals in this checklist identified in the assessments.

The high chest, examined by the author, is similar to one illustrated in Myers and Mayhew, New London County Furniture, p. 19, no. 10. The shaping of the front apron and absence of knee returns are distinctive.

Perkins, Old Houses of the Ancient Town of Norwich, p. 217; and J. C. Griste, History of the Griste Family in America (Morris, Ill., 1901), p. 1 (online transcription).

Courier, May 31, 1797; September 29, 1802.

Norwich Packet, February 7, 1792; Courier, March 1, 1798; March 4, 1801. In 1795 and 1796 a David Hamilton was master of the schooner Anna, a ship of which Kelley was part owner. In 1797 Hamilton took over the helm of the schooner Lucy; he died in Newburgh, New York, the following year. Presumably, Hamilton the mariner and cabinetmaker are one and the same. Penrose R. Hoopes, Shop Records of Daniel Burnap (Hartford: Connecticut Historical Society, 1958), p. 55. Hoopes mistakenly records Kelley as being in Norwich, Vermont; however, the original manuscript (CHS) makes no such designation. Burnap would have known him from his apprenticeship days in Norwich. The Connecticut Ship Database (Mystic Seaport) records ten ships in which Kelley invested between 1795 and 1813. Four additional ships in which he had ownership interest were seized by French privateers between 1797 and 1800 and the cargo confiscated. Kelley received insurance settlements as partial recovery for his losses in two instances (Greg H. Williams, The French Assault on American Shipping, 1793–1813 [Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2009], pp. 104, 248, 271, 303).

Isaac Lathrop ad in the Norwich Packet, October 2, 1788. The chairs are illustrated in Trent and Nelson, “New London County Joined Chairs,” pp. 79, 93, figs. 20, 21. Isaac Huntington account book, p. 24, CHS.

Norwich Packet, May 5, 1791; January 15, 1795; June 2, 1796; June 20, 1799. Weekly Register (Norwich, Conn.), August 28, 1792; September 10, 1793. Eleazer Hazen’s identity, uncertain in earlier publications, is based on the description of him as a cabinetmaker in Tracy E. Hazen, The Hazen Family in America (New Haven, Conn.: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor Co., 1947), p. 144. He married in Worthington, Massachusetts, in 1798 and later moved to Waterville, New York, and Ravenna, Ohio.

Isaiah Tiffany account book, CHS. For a summary, see Newton C. Brainard, “Isaiah Tiffany’s Ledger,” Connecticut Historical Society Bulletin 17, no. 4 (October 1952): 30–32. New London Gazette, July 22, 1768. A cherry chest-on-chest at Yale, illustrated in Gerald W. R. Ward, American Case Furniture in the Mabel Brady Garvan and Other Collections at Yale (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1988), p. 182 (acc. no. 1984.32.40), is inscribed on the underside of the upper case with initials that have been interpreted as “IT.” A mahogany blockfront bureau with similar feet and a history of ownership in the Jonathan Trumbull family of Lebanon is illustrated in Antiques 147, no. 3 (March 1995): 345 (C. L. Prickett ad). Trumbull purchased a “Case of Draws without trimming . . . 32.0.0 [and] Dressing Table without trimming . . . 8.0.0” from Tiffany in 1749/50. Whether the illustrated pieces are Tiffany’s work is uncertain; they appear to postdate the ledger entries by at least two decades.

Tax assessments, Warren Collection, CHS. Elijah Tracy ad in the Norwich Packet, April 7, 1796. The chest-on-chest is owned by CHS (acc. no. 1965.53.0) and illustrated in Myers and Mayhew, New London County Furniture, no. 70. In the catalogue description the authors note the similarity of the writing on the case to that of Tracy. The chest has chamfered corners similar to those of the Huntington shop. A one-drawer blanket chest, branded “EB Tracy,” is illustrated in Antiques 99, no. 2 (February 1971): 268. Two bureaus, branded by family members, demonstrate additional evidence of this shop tradition’s output of case furniture. A straight-front Chippendale bureau with shaped top and chamfered corners, branded “A. D. Allen” by Tracy’s son-in-law, probably working in Windham, is illustrated in Kirk, Connecticut Furniture, no. 70. A federal bureau, branded “S. Tracy” by Ebenezer’s nephew Stephen, may predate the latter’s move to Cornish, New Hampshire, in 1810 (Historic Deerfield, acc. no. 91.262, illustrated in database). For Tracy’s dealings with John Avery, see Amos G. Avery, Clockmakers and Craftsmen of the Avery Family (Hartford: Connecticut Historical Society, 1987), p. 71. Mangrove is known for its resistance to water. Several species are known, all of which grow in tropical and subtropical tidal areas of the West Indies. The white mangrove is also known as buttonwood. Its value in the Tracy inventory is low, about one-tenth that of mahogany. See Evans, American Windsor Chairs, pp. 285–302.