Ceremonial armchair, Britain, ca. 1750. Mahogany with beech. H. 49" (with modern arched board added to the crest), W. 21 1/2", D. 24 1/2" (seat). (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, photo, Hans Lorenz.) The footstool is a reproduction.

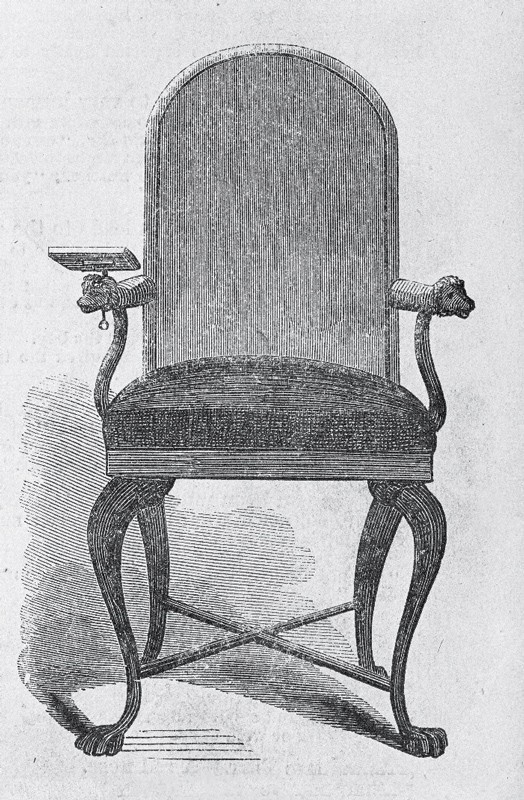

Engraved image of the armchair illustrated in fig. 1 published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, June 16, 1866.

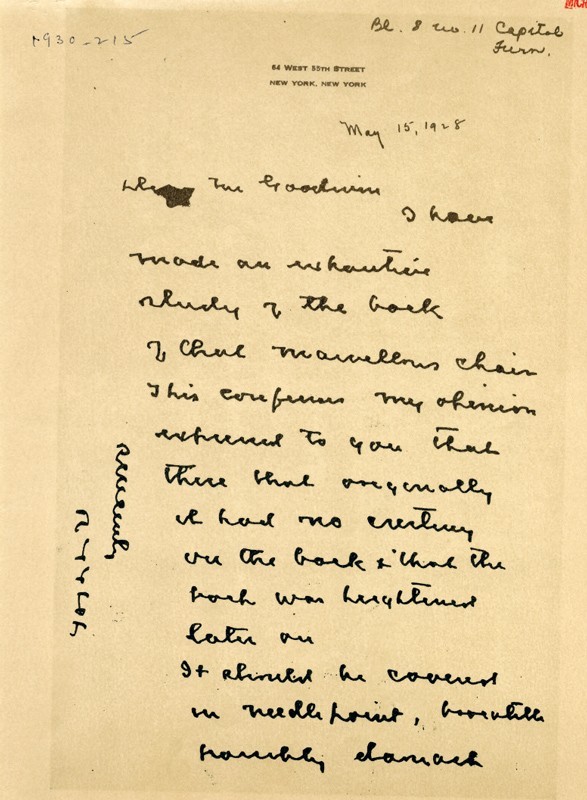

Letter from W. H. Soane to W.A.R. Goodwin, May 15, 1928.

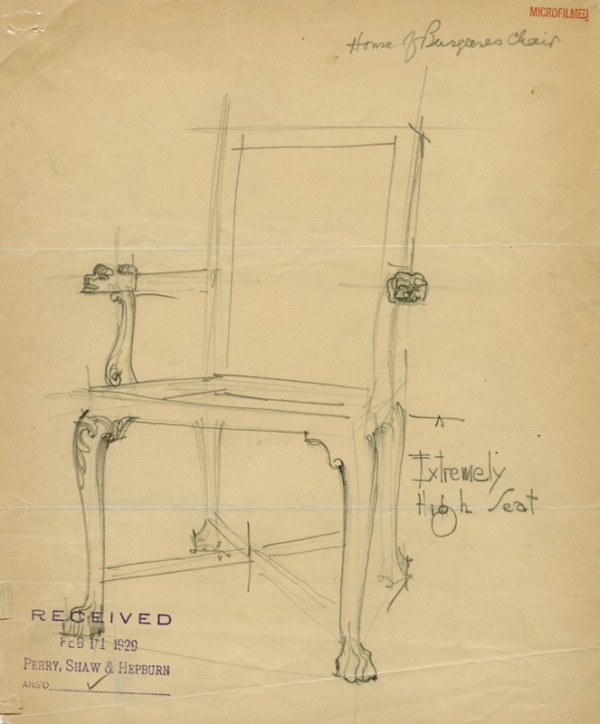

Drawing of the armchair illustrated in fig. 1 marked "RECEIVED / FEB 11 1929 / PERRY, SHAW & HEPBURN."

Photograph of a hall vignette in the “Girl Scouts Loan Exhibition,” New York, 1929. The armchair is visible in the left rear corner.

John Singleton Copley, Henry Laurens, 1782. Oil on canvas. 54 1/4" x 40 5/8". (Courtesy, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., gift of Andrew Mellon, 1942.)

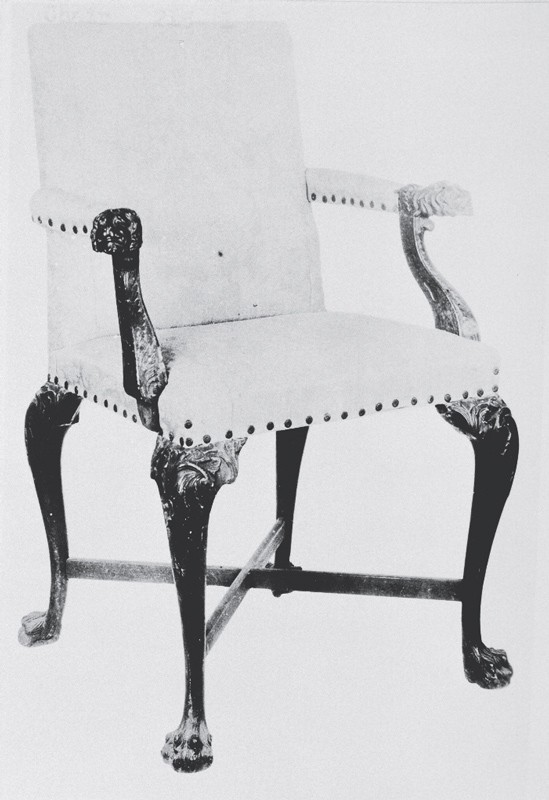

Photograph of the armchair illustrated in fig. 1, taken ca. 1930.

Photograph of the armchair illustrated in fig. 1, taken in 1963.

Photograph of the armchair illustrated in fig. 1, taken in 1977. The arched crest and new leather upholstery were added in preparation for the chair’s exhibition in “Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia: The Product of Mind and Hand,” Virginia Museum, Richmond, 1978. Wallace Gusler curated that show.

Backstool, Britain, ca. 1750. Mahogany with oak, cherry, beech, and ash. H. 40", W. 25", D. 22" (seat). (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Friends of Colonial Williamsburg Collections Fund and the TIF Foundation in Memory of Michelle A. Iverson; photo, Craig McDougal.) The other backstool has red pine in its construction.

Details showing the knee carving on the armchair illustrated in fig. 1 (left) and one of the backstools represented by the example illustrated in fig. 10 (right).

Details showing the paw feet on the armchair illustrated in fig. 1 (left) and one of the backstools represented by the example illustrated in fig. 10 (right).

Details showing the side knee blocks of the left front legs of the armchair illustrated in fig. 1 (left) and one of the backstools represented by the example illustrated in fig. 10 (right). On the armchair knee block, the carver snapped off the volute and had to modify his design.

Detail showing a rounded rear post on one of the backstools, represented by the example illustrated in fig. 10.

Detail showing replaced front and side rails on the seat frame of one of the backstools, represented by the example illustrated in fig. 10.

Detail showing the back attachment of one of the backstools, represented by the example illustrated in fig. 10.

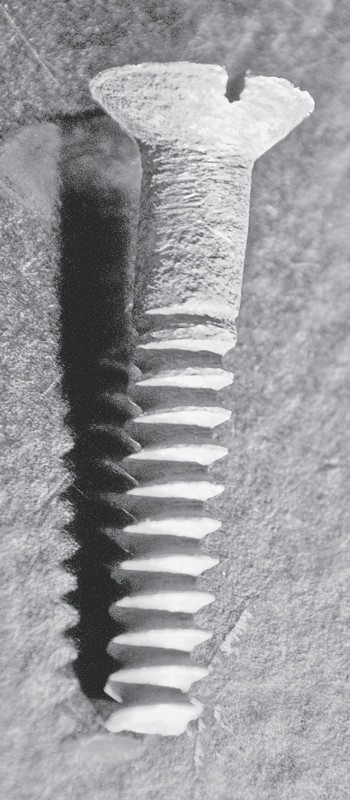

Detail of a screw used in the back attachment of one of the backstools, represented by the example illustrated in fig. 10.

Detail showing altered knee blocks on one of the backstools, represented by the example illustrated in fig. 10.

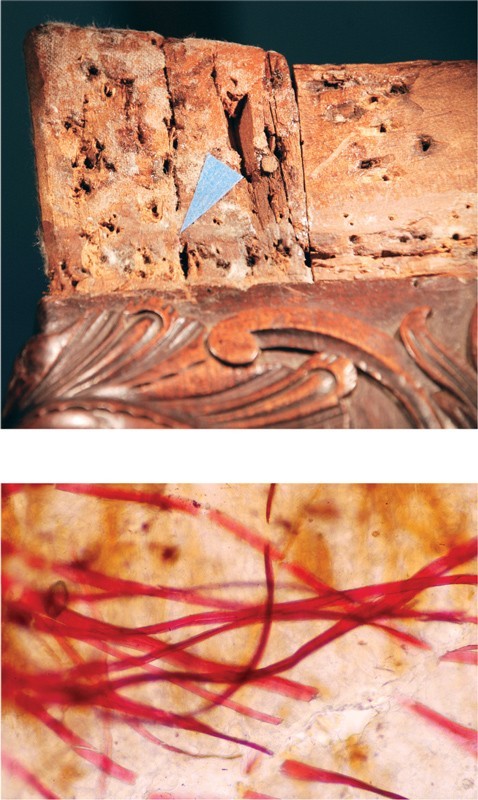

Details showing remnants of the original red wool (top) and silk (bottom) surviving on one of the backstools, represented by the example illustrated in fig. 10.

Detail showing the brass nail pattern on one of the backstools, represented by the example illustrated in fig. 10.

Armchair illustrated in fig. 1 with upholstery removed.

Detail showing a remnant of the original red silk show cloth on the armchair illustrated in fig. 1.

Detail showing the brass nail pattern on the armchair illustrated in fig. 1.

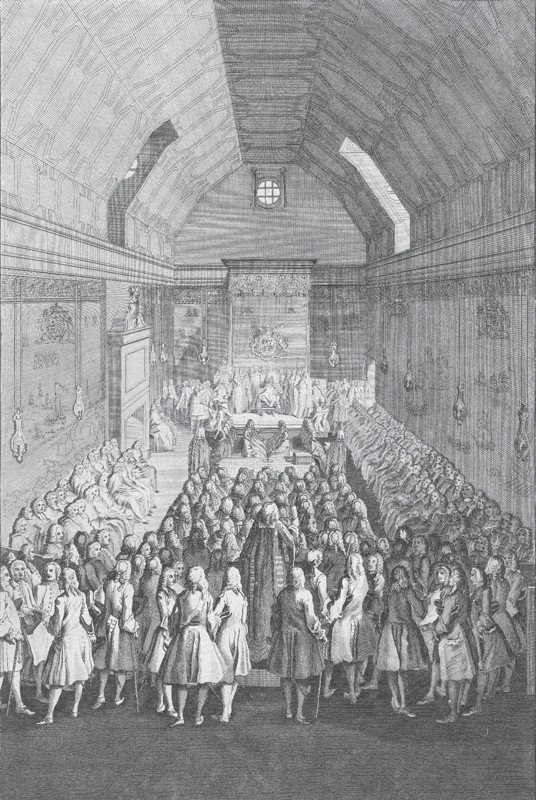

A View of the House of Peers. The King Sitting on the Throne, the Commons Attending Him at the End of the Session, 1755, engraved by B. Cole, London, 1755. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Ceremonial armchair with carving attributed to the shop of Henry Hardcastle (d. 1756), Charleston, South Carolina, 1755–1756. Mahogany with sweet gum. H. 53 3/8", W. 37 3/8" (arms). (Collection of the McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail of the mortises and screw holes in the crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 25.

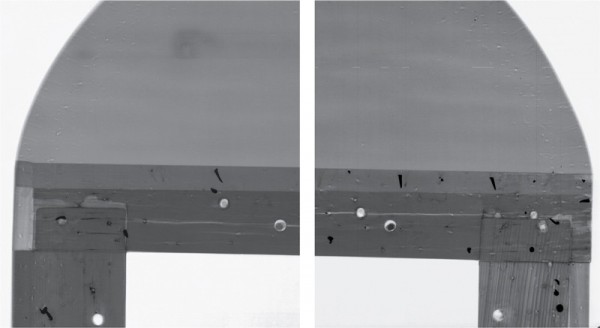

X-radiographs of the crest rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 1.

Detail showing the original placement of a mahogany strip added to the armchair illustrated in fig. 1 during the nineteenth century.

Detail showing the partial mortise in the top of the mahogany strip and alignment with a patched partial mortise in the crest rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 1. The marks left by the lead and outer cutter of the center bit are visible at the bottom of the mortise on the strip and below the patch on the crest.

Detail showing a center bit similar to the example used to bore the mortises in the mahogany strip and crest rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 1.

Detail showing the partial mortises on the mahogany strip and crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 1 with a patch removed.

Detail showing the rabbeted upper rear edge of the crest of the armchair illustrated in fig. 1.

Armchair, backstool and reproduction stool illustrated in this article, with red silk, wool upholstery, and fringe. (Photo, Craig McDougal.)

The ceremonial armchair made for the royal governor’s use in the Capitol Building at Williamsburg, Virginia, is one of the most iconic seating forms with an American history, but its place of manufacture, original appearance, and specific function have been the subject of decades of debate (fig. 1). Furniture historians have traditionally attributed the chair to England or Williamsburg; speculated about whether the crest was originally straight, arched, or fitted with a royal coat of arms; and suggested that the chair could have been used in the General Court or the Council Chamber. Although little new scholarship pertaining to the governor’s chair has emerged over the last fifteen years, the recent discovery of two related backstools owned by a descendant of an eastern Virginia family prompted new research (see fig. 10). This essay will show how the structural and upholstery evidence of these three chairs sheds light on their origin, ceremonial context, changes in design, and how those objects were perceived.[1]

History and Historiography

The history of the armchair is essential to understanding how it looks today. Although presumably made for the second Capitol Building in Williamsburg and taken to Richmond when the seat of government moved there in 1780, the earliest reference to the chair is in the June 16, 1866, issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (fig. 2). Leslie reported that the chair was “made in England, and sent over, with the stoves, as presents for the House of Burgesses.” His stylized illustration shows the chair with cross-stretchers; an upholstered seat, back, and arms (which he described as “lined in red”); a book rest attached to the lion-head terminal of the left arm; and an arched crest and stiles faced with wooden strips. Tradition maintains that the chair was subsequently stored in the attic of the State Capitol Building, then given to William McKie Dillard (1856–1902), who was doorkeeper of the House of Delegates. Richmond antiques dealer Hugh Proctor Gresham purchased the chair from Dillard’s son and sold it to a local dealer named J.F. Biggs by 1928, when John D. Rockefeller’s agent the Reverend W. A. R. Goodwin acquired the chair for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.[2]

The earliest accession records indicate that the chair was sent to the New York City firm W.H. Sloane for restoration to be supervised by R.T.H. Halsey. That work included removal of the arched crest and nineteenth-century upholstery, repair of damaged or missing areas of the rear feet, and installation of new upholstery (figs. 3, 4). When the chair was displayed at the “Girl Scouts Loan Exhibition” in 1929, it had a square back, cross-stretchers, and damask upholstery (fig. 5). Aside from removal of the nineteenth-century stretchers and replacement of the missing knee blocks, little was done to change the design of the governor’s chair until 1977, when a board was added to the crest to elevate the back and create an arched profile. From that point until now, scholars have assumed that the chair originally had a “rounded crest,” which “had been cut off, leaving a short square back.” In changing the profile, Colonial Williamsburg curators and conservators looked to contemporaneous British and southern ceremonial chairs, most of which have tall backs. They also noted that the seat height mandated the use of a footstool, as was the case with the thrones of George II and III and the chair depicted in John Singleton Copley’s portrait of Henry Laurens, who served as governor of South Carolina from 1775 to 1776 (fig. 6).[3]

The most significant scholarship on the governor’s chair is presented in Wallace Gusler’s Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia, 1710–1790 and Ronald L. Hurst and Jonathan Prown’s Southern Furniture, 1680–1830: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection. Gusler theorized that the chair was made for “the Governor’s [use] . . . in the General Court,” that it was likely displayed beneath an elaborate canopy, and that “a set of similar chairs of regular height may have accompanied it.” He also pointed out relationships between the governor’s chair and a master’s chair made for Williamsburg Masonic Lodge Six, specifically the use of lion-head arm terminals, arm supports with leaf carving on their outer faces and geometric designs on the inner face, and knees with asymmetrical scroll and acanthus. Based on those shared details, Gusler attributed the construction of the governor’s chair to the Anthony Hay shop and the carving to James Wilson, a London-trained artisan who advertised in Williamsburg in 1755. Hurst and Prown’s interpretation differed in two respects. They felt that the chair was probably made for the governor’s Council Chamber, and that its place of manufacture could have been either Britain or Williamsburg.[4]

Upholstery Evidence: Photographic

Photographs in the accession file for the governor’s chair document five different upholstery treatments. The earliest upholstery, likely done under the supervision of New York decorator Ernest LoNano before 1929, featured a damask show cloth and brass nails with central bosses and milled edges spaced approximately two inches apart (fig. 7). By 1963 the damask had been replaced with leather, and small brass nails were applied, end to end, around the lower edge of the arms and seat, rear edges of the crest and rear stiles, and lower edge of the rear seat rail (fig. 8). In 1977 Williamsburg conservators removed the leather, added an arched board to the crest, and applied new leather upholstery and nails. The tight upholstery lines from that treatment reflected new understanding about period upholstery practices (fig. 9). Additional information gleaned from the study of British ceremonial seating led the foundation’s curators and conservators to replace the leather with red silk velvet and apply fringe on the lower edge of the arms and seat and rear edges of the back stiles in 1985. That treatment remained in place until 2012, when the upholstery was removed to facilitate comparison of the frame with the frames of the recently discovered backstools.[5]

The Backstools

In the summer of 2012, Fredericksburg antiques dealer Bill Beck sold the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation two backstools with ornament executed by the carver of the governor’s chair (fig. 10). The backstools were described as a “Pr. Mahogany side chairs [with], paw feet, acanthus carved knees, [and] upholstered backs” in the October 6, 2011, estate sale of William N. Wilbur. His deceased wife, Mary Tyler McCormick Wilbur (1915–1981), had descended from several eastern Virginia families. Microanalysis verified the use of several secondary woods, including red pine, which provided strong evidence that the backstools and governor’s chair were made in Britain.[6]

All three chairs have sculptural paw feet and knees decorated with asymmetrical shell and acanthus carving, a formula common in British furniture of the mid-eighteenth century (figs. 11, 12). This knee design also occurs in Boston and New York furniture, but the carving on those objects is not as professionally rendered as that on the backstools and governor’s chair. On the latter objects, the leaf and shell motifs are subtly modeled and shaded with carefully regulated flutes made with a very small gouge. Other than minor differences in scale and one design adjustment that reflected a mistake on the part of the carver (fig. 13), the foot and knee carving on the backstools and armchair is nearly identical.[7]

Structural details suggest that the shop responsible for the backstools made them from stock-in-trade side chairs with over-the-rail upholstery, probably to fulfill a large order that also included the governor’s chair. Evidence of conversion is the rounded back edge of the rear posts (fig. 14), replaced seat rails (fig. 15), and unusual attachment of the back, which was simply glued and screwed to the sawn-off rear posts of the repurposed side chairs (fig. 16). The screw threads are die-cut rather than filed, indicating a mid-eighteenth-century date (fig. 17). On most backstools, the stiles of the back frame extend below the lower rail and are set in notches in the side rails. The addition of an upholstered back, which would have been about 1 1/2 inches thicker than a splat, necessitated the use of longer side rails. Because this changed the geometry of the seat, the front rail had to be replaced as well. The maker simply sawed through the original beech front and side rails, leaving their glued-in tenons in place (see fig. 15). Because the traditional joint location had been compromised, he cut new mortises that were more centered on the leg stock and lower than the originals. This new tenon location required the use of front and side rails that descended lower at their juncture with the legs and required alteration of the knee blocks (fig. 18). The blocks, which were originally attached to the stiles of the front legs, were sawn and chopped out to fit over and under the new rails.

The upholstery evidence on the backstools supports the theory that they are period conversions made to accompany the governor’s chair. Fragments of the original dark red silk show cloth are trapped under nails on the front (fig. 19), and fragments of matching red wool are under nails on the back. Period brass nail shanks, which occur at approximately two-inch intervals on both the back and seat frame, indicate that the backstools were upholstered at the same time (fig. 20).

The Governor’s Chair

Subsequent examination of the frame of the governor’s chair revealed tiny fragments of red silk and matching red wool in the same contexts as those on the backstools, along with brass nail shanks at two-inch intervals (figs. 21-23). The shanks on the front and side rails of the seat and arms are approximately one inch above the lower edge, denoting the use of one-inch fringe. Presumably, the footstool received a similar treatment. As is the case with their nearly identical carving, the upholstery evidence on the governor’s chair and backstools supports the theory that they were purchased as a suite. If the suite were made for use in the Council Chamber, a dozen backstools would have been required to seat each member.

With its more elaborate upholstery, the governor’s chair reflected that person’s position as the Crown’s representative in Virginia. As previous scholars have suggested, the chair may have been displayed under a canopy and raised on a platform similar to those shown in the engraving A View of the House of Peers. The King Sitting on the Throne, the Commons Attending Him at the End of the Session, 1755 (fig. 24). Like the armchairs on either side of George II’s throne, the backstools would likely have sat at floor level.[8]

Scholars have also speculated about the display of a royal coat of arms with the governor’s chair, and whether that armorial was attached to or suspended above the crest. Precedent for an attached armorial can be found in contemporaneous ceremonial seating from Britain as well as an armchair made for the royal governor of South Carolina (fig. 25). The coat of arms on the South Carolina chair is missing, but mortises and screw holes in the back of its crest demonstrate that the chair had an armorial attached with a wrought-iron armature (fig. 26). X-radiography and visual examination of the wood surfaces and nail shanks on the Virginia governor’s chair indicate that the crest was reduced in height and rabbeted on the back but uncovered no evidence for an attached coat of arms (fig. 27). Although these alterations make it impossible to exclude an attached or integral coat of arms as part of the original design, it is far more likely that the chair originally had a square back and a coat of arms suspended above. The crest rail shows no sign of catastrophic damage, which would likely have been present if an integral coat of arms broke off, or evidence for the attachment of an armorial.[9]

When the governor’s chair was upholstered in 1977, two strips of mahogany were removed from the frame and placed in storage, where they remained until 2013. Nail evidence indicates that the long strip was attached to the left rear stile (fig. 28) and the shorter strip to the right rear stile. The discovery of a partial mortise drilled in the top of the long strip led to a closer study of the crest, which had been patched at both ends (fig. 29). The mortise was cut with a center bit, which had a short lead and outside cutter (fig. 30). Removal of one of the patches on the crest revealed another partial mortise that matched the one on the mahogany strip (fig. 31). These mortises and the one-half-inch rabbet on the back edge of the crest (fig. 32) were probably related to the attachment of an arched extension, installed before Frank Leslie illustrated the chair in 1866 (see fig. 2). The individual responsible for that work probably cut off the top edge of the crest, presumably to remove a surface compromised by holes from upholstery nails. If the stock used to make the crest was of the same dimensions as the stiles of the back frame, which is the case with the backstools, only one half inch is missing from the top. That would have been enough space to attach the original upholstery. The back of the governor’s chair did not have webbing like the backstools. To support the foundation, the upholsterer nailed a single piece of linen to the front face of the back frame of the governor’s chair. In contrast, the seat frame of that chair has nail sites from period webbing.[10]

Between the 1930s and 1960s, original materials used to cover upholstered seating furniture made or used in the American colonies was often removed and, more often than not, discarded. Important evidence was lost in the process. Although the governor’s chair, too, was reupholstered by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, the process was well documented, and each element that was removed from the frame was preserved, making it possible to meticulously examine the piece in order to return it to what we believe was its original appearance (fig. 33).[11]

No study of this type can be undertaken in isolation. Although the physical evidence on the frame of the governor’s chair was the most important consideration in determining its likely original appearance, paintings and prints depicting British ceremonial chairs provided a wealth of information about the upholstery and use of contemporaneous examples. Another important source consulted during this study was Colonial Williamsburg’s extensive collection of seating furniture with original upholstery, which documents many methods used by early craftsmen to create the various contours and profiles. Decades spent intensely studying those objects provided the basis for our understanding of period techniques and reinforced the conclusions drawn from the evidence surviving on the frame of the governor’s chair. The results of the foundation’s commitment to the study and preservation of upholstered furniture will be published next year in a lavishly illustrated book, Reading the Evidence: The Craft and Preservation of Early Seating Upholstery by Leroy Graves.

Accession file no. 1930-215, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (hereafter CWF), Williamsburg, Va. Wallace B. Gusler, Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia: The Product of Mind and Hand (Richmond: Virginia Museum, 1978), pp. 11, 12, fig. 4; Wallace B. Gusler, Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia, 1710–1790 (Richmond: Virginia Museum, 1979), pp. 70–72, fig. 46; Morrison H. Heckscher and Leslie Greene Bowman, American Rococo, 1750–1775: Elegance in Ornament (New York: Harry N. Abrams for the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1992), p. 167, fig. 39; Ronald L. Hurst and Jonathan Prown, Southern Furniture, 1680–1830: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection (New York: Harry N. Abrams for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1997), pp. 185–89, no. 52.

The Capitol Building was completed ca. 1754. Accession file no. 1930-215, CWF. An October 25, 1989, memo from John O. Sands states that “Ms. Vera Goodman . . . inquired some months ago about the Governor’s chair in the CW collections. She thought that it looked like a chair that her father had described playing in as a child of three or four, then the property of his great uncle. . . . She suggests that the chair was given to William McKie (Mack) Dillard (1856–1902), who was the doorkeeper of the House of Delegates. It appears that the chair had been relegated to storage, and was given to Dillard, probably upon retirement. On his death, it passed to his brother Thomas Massenburg Dillard (1848–1929), of 211 South High Street, Blackstone, Virginia. That house still stands, and it was there that her father played on the chair. Apparently, upon the death of T. M. Dillard, it went into the hands of an antiques dealer.” This account of the ownership of the chair after William McKie Dillard differs from others, which maintain that the piece passed directly to his son.

Accession file no. 1930-215, CWF. Colonial Williamsburg furniture conservator Albert Skutans added an arched board to the crest between 1977 and 1978, when the chair was being readied for exhibition in “Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia: The Product of Mind and Hand.” Hurst and Prown, Southern Furniture, p. 187. Gusler cited the throne of George III in Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia, p. 70; and Hurst and Prown illustrated and discussed A View of the House of Peers. The King Sitting on the Throne, the Commons Attending Him at the End of the Session, 1755, an engraving by B. Cole of London (p. 187). Hurst and Prown also illustrate a chair made for use by the royal governor of South Carolina. That object has a tall back and a crest rail with mortises and screw holes in the back, presumably from the attachment of a carved coat of arms.

Gusler, Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia, pp. 70–74, 103–9. Hurst and Prown, Southern Furniture, pp. 185–89, no. 52.

The leather upholstery applied in 1977 or 1978 was subsequently tufted.

See accession file no. 2012-25, CWF, for a copy of the microanalysis (Alden Wood I.D., October 27, 2011), a copy of the sale advertisement, and a genealogical report.

For Boston chairs with this carving formula, see Luke Beckerdite, “Carving Practices in Eighteenth-Century Boston,” in New England Furniture: Essays in Memory of Benno M. Forman (Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1987), pp. 123–36. Most of the New York pieces with this knee design are card tables, most dating between 1760 and 1780. See accession file no. 2012-25, CWF.

Gusler, Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia, pp. 70–72; Hurst and Prown, Southern Furniture, pp. 185–87.

For more on the South Carolina chair, see Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “The Royal Governor’s Chair: Evidence of the Furnishing of South Carolina’s State House,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 6, no. 2 (November 1980): 1–32. Rauschenberg attributed the chair to the cabinet firm of Elfe and Hutchinson based on a March 14, 1758, entry in the journal of the Commons House of Assembly, which recorded their bill for “Furniture for the Council Chamber amo £728.2.6”; and Act 874 of the 1758 Statutes at Large of South Carolina, which noted that the firm’s “Extraordinary” charge was for chairs and tables for the Council Chamber (pp. 8–9). Luke Beckerdite later attributed the carving on the South Carolina governor’s chair to the shop of Henry Hardcastle, a British-trained carver who immigrated to New York by 1751 and moved to Charleston, South Carolina, between July 1755 and the artisan’s death in October 1756 (Luke Beckerdite, “Origins of the Rococo Style in New York Furniture and Interior Architecture,” American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite [Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1993], pp. 32–37). According to Beckerdite, the entries cited by Rauschenburg do “not mention the Governor’s chair and probably referred to chairs and tables for the members of the Upper House of Assembly.” He further notes that Elfe and Hutchinson’s charges reflect the exchange rate for Charleston and English currency, which was 7:1 in 1758 as compared with 1.7:1 in New York and 1.6:1 in Pennsylvania. Beckerdite suggests that the South Carolina governor’s chair was ordered in 1756, citing “the treasurer’s advance to pay tradesmen’s bills for furniture on July 6 of that year, Hardcastle’s working dates in Charleston, and an order for a mace for the governor, robes for the speaker, and a gown for the clerk in March 1756.”

The author thanks Colonial Williamsburg furniture conservator Albert Skutans for information pertaining to the seating frame in 1977.

Wallace Gusler and Albert Skutans were responsible for preserving all of the components added to the frame.