Wardrobe, Charleston, South Carolina, 1785–1790. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with white pine and cedar. H. 91", W. 53 1/4, D. 25 3/4". (Kaufman Americana Collection; photo, Dirk Bakker.)

Double-top sideboard, Charleston, South Carolina, 1790–1800. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with ash, tulip poplar, and white pine. H. 45 1/2", W. 66 1/2", D. 31". (Courtesy, Rivers Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

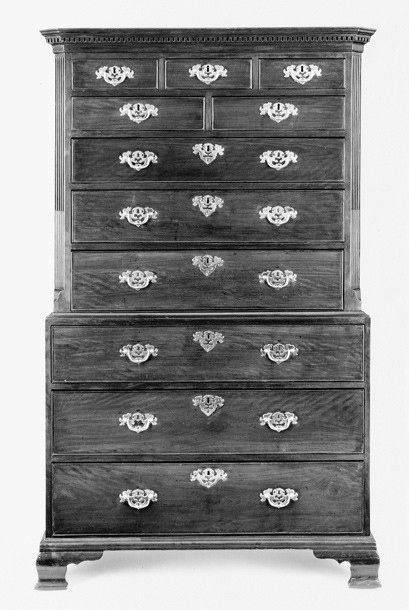

Double chest, Charleston, South Carolina, 1750–1760. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with cypress and white pine. Descended in the Holmes family. H. 72", W. 44 5/8", D. 24". (Courtesy, Charleston Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the “WA” cipher stamped on the lower case of the double chest in fig. 3. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bradford L. Rauschenberg and John Bivins, Jr., The Furniture of Charleston, 1680–1820. Frank L. Horton Series. 3 vols. Winston-Salem, N.C.: Old Salem, Inc., and the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 2003. Vol. 1, Colonial Furniture. Vol. 2, Neoclassical Furniture. Vol. 3, The Cabinetmakers. xxxv + 1388 pp., numerous color and bw illus., maps, appendices, bibliography, concordance, index. $325.00.

The much-anticipated work of Bradford L. Rauschenberg and John Bivins, Jr., The Furniture of Charleston, 1680–1820, lends proof to the adage, good things come to those who wait. After more than twenty years of fieldwork and research, the authors have produced a monumental tome. Composed of three volumes with more than one thousand pages, it features hundreds of color and black and white photographs of more than four hundred pieces of furniture plus maps, appendices, bibliography, concordance, and index. Weighing nearly sixteen pounds, the book is a goldmine of information for furniture scholars, collectors, and dealers interested in the Carolina Lowcountry’s unique material culture. As the preface by Gary J. Albert notes, it combines “Rauschenberg’s tenacious research skills and mastery of microscopic wood analysis” with “Bivins’ encyclopedic knowledge of all American furniture forms and unique insight into an artisan’s approach to construction” (p. ix).

Recognizing that an opus of this size cannot be produced in isolation, the authors acknowledge generously the many individuals and institutions whose support, both financial and otherwise, made the book possible. The research was partially funded by the Research Tools and Reference Works program of the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Chipstone Foundation provided valuable support for the expense of extensive color photography. The book has been published as part of the Frank L. Horton series, an endowed fund created by the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA) especially for the publication of monographs on southern crafts and craftsmen. Previous titles in the series include John Bivins, Jr.’s The Furniture of Coastal North Carolina (1988), Benjamin H. Caldwell, Jr.’s Tennessee Silversmiths (1988), and Harold Eugene Comstock’s The Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley Region (1994). As the fourth and most recent installment in this distinguished series, The Furniture of Charleston symbolizes MESDA’s ongoing commitment to the serious study of southern material culture.

In the first few pages, Brad Rauschenberg provides furniture scholars with a noteworthy anecdote for the historiography of their field. For decades, the renaissance of interest in southern furniture has been attributed to the reaction sparked by a comment made at the 1949 Williamsburg Antiques Forum by Joseph Downs, curator of the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, that “nothing of artistic merit was made south of Baltimore.” Rauschenberg demonstrates that Milby Burton (1898– 1977), then director of the Charleston Museum, had addressed this issue fully eight years earlier in a 1941 interview with a Richmond, Virginia, newspaper. In his published remarks, Burton decried the established biases of both “the Plymouth crowd and the Jamestown crowd” and made the pithy remark that he was “so damned tired of hearing the Boston crowd infer there was no silver or furniture making in the South” (p. xxvi).

Published in 1955, Milby Burton’s book Charleston Furniture, 1700–1825 launched the first serious examination of Charleston’s early furniture production. For decades, the subject then lay dormant until 1986, when John Bivins penned a significant article, “Charleston Rococo Interiors: The ‘Sommers’ Carver,” in the fall issue of the Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts. Since then, interest in Charleston furniture has skyrocketed, both in scholarly venues and in the marketplace. Important monographs in recent issues of this journal have included Luke Beckerdite’s analysis of the French Huguenot influence on South Carolina’s seventeenth-century furniture, Thomas Savage’s research on Martin Pfeninger and Charleston’s pre-Revolutionary German cabinetmakers, and John Bivins’ discussion of Scottish, German, and Northern influences on Charleston’s post-Revolutionary cabinetwork (each in American Furniture 1997), as well as an examination by Maurie D. McInnis and the author of this review of the New York City cabinetmakers Deming and Bulkley and their impact on Charleston’s nineteenth-century furniture (American Furniture 1996). Similarly, in Southern Furniture, 1680–1830: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection (1997), Ronald L. Hurst and Jonathan Prown shed new light on a number of pivotal Charleston objects, and, in recent years, a distinguished coterie of southern scholar-dealers—Sumpter Priddy, Deanne Levison, Milly McGehee, Harriett and Jim Pratt, and George Williams—have made groundbreaking discoveries in the realm of Charleston furniture studies. Today, The Furniture of Charleston stands on top of this mountain of research, which collectively presents a powerful tribute to the life’s work of Frank L. Horton and the research resources he has created at MESDA.

As the introduction states, this book is not simply “a catalog” of the Charleston furniture in MESDA’s collection; rather, it is a highly detailed analysis of the cabinetmaking industry in a sophisticated urban center, Charleston, and a compilation of the known furniture it produced. Arranged chronologically, the first two volumes move from the colonial period in volume one to the neoclassical period in volume two, and each volume carefully analyzes the construction and stylistic features that allow shop groups to be identified. In the section on neoclassical bedsteads, for example, a chart examines the characteristics of forty surviving bedsteads and suggests the presence of seven distinct shop groups that either employed or contracted with at least six turners and three carvers between the years 1785 and 1815 (p. 805). Throughout the book, the authors succeed in building important relationships between the individual objects and the region’s supporting documentation. So, while Charleston’s most famous cabinetmaker, Thomas Elfe (ca. 1719–1775), remains elusive without the discovery of a single signed, labeled, or documented example of his production, the authors’ expert analysis showcases his surviving day books for the years 1768 to 1775 and how they illuminate the intricacy of Charleston’s early cabinet trade.

Through furniture, the authors illustrate how Charleston evolved from an early outpost of the British colonial empire into a thriving capital and cultural center. Founded in the late seventeenth century by an assortment of British, French, Dutch, German, Swiss, and Sephardic Jewish settlers, Charleston became a place where by 1740 Eliza Lucas Pinckney could say, “the people live very Gentile and very much in the English taste.” Deeply imbued with British style, Charleston’s colonial furniture reflects the city’s rising level of sophistication. Charleston’s eighteenth-century cabinet wares typically feature paneled backs, full or three-quarter length dustboards, center drawer muntins, and other construction characteristics that typify urban British craftsmanship. By 1770 Charleston possessed one of the most professional and diverse cabinetmaking communities in British North America. Composed of English, Scottish, French, German, Swedish, and African American professionals, Charleston’s cabinetmakers fashioned some of the finest furniture produced in early America. The Edwards library bookcase, for example, with its complex construction, triple serpentine form, polychrome marquetry and ivory inlay, made in Charleston between 1770 and 1775, is, as the authors describe, “unparalleled in American furniture” (p. 168). In his 1997 article on this piece and its relationship to the German-born cabinetmaker Martin Pfeninger (d. 1782), Savage explains how it presents “a synthesis of British and Continental structural and decorative features within the context of Charleston taste and patronage.”[1]

After the Revolution, Charleston’s urbane consumers continued to support talented emigré craftsmen. In the city’s post-Revolutionary economic and cultural environment, Scottish furniture makers such as Robert Walker (1772–1833), who arrived in 1793 with copies in hand of Thomas Sheraton’s The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book and The Cabinet-Makers’ London Book of Prices, competed with German- and English-born craftsmen like Jacob Sass (1750–1836) and John Ralph (ca. 1743–1801), whose businesses had been established in Charleston some twenty years earlier. As Germanic features first seen in the Edwards library bookcase continued well into the 1790s (see fig. 1), and Scottish furniture forms such as the double-top sideboard became relatively commonplace in Charleston (see fig. 2), the city’s neoclassical furniture expressed the happy coexistence of these disparate styles. By the early nineteenth century, Charlestonians could boast a cosmopolitan culture that combined their native-grown society with imported influences from abroad as well as those from the northern states, most especially New York and Massachusetts. The authors fully describe the impact of imported northern-made furniture on early nineteenth-century Charleston’s cabinet trade, how it influenced ’s eventual decline.

While the organization of these first two volumes seems innovative, it is perhaps not likely to be repeated. Each piece of furniture is assigned a unique number based on the period (early, colonial, neoclassical), the form (case furniture, tables, chairs, beds), and finally the sequence in which it appears in the book. So, for example, the first colonial-period table is CT-1 and so forth. Each piece is then catalogued with a complete discussion of its primary and secondary woods, dimensions, construction details, markings or inscriptions, and provenance. Honed by MESDA’s many years of field research, the descriptions of construction seem particularly excellent, and the concordance allows readers to find every page on which a particular piece might be mentioned. However, due to the page design and layout, this reader found the overall organization frequently difficult to follow, and to track a particular detail, it was sometimes necessary to use all three volumes simultaneously, flipping pages from volume one to volume two to the references to a specific cabinetmaker contained only within volume three.

The third volume features a comprehensive biographical dictionary of all the furniture-related craftsmen discovered by MESDA’s documentary research on the Carolina Lowcountry. With more than six hundred artisans listed, it cites all the known references to each one found in the region’s court records, newspaper advertisements, directories, and manuscripts, both published and unpublished. Also included are photographs of all the known signed, labeled, or documented examples of an artisan’s work. The volume contains three appendices: an alphabetical listing of tradesmen, a chronological listing, and tradesmen clustered by street address intended, as Rauschenberg notes, to provide “a rare glimpse into the relationships and evolution of artisans and partnerships, as well as the rise and fall of business” (p. 871). Unfortunately, this volume does not include a fourth appendix that divides the furniture-related artisans into their specific subcategories: joiners, turners, cabinetmakers, chair makers, carvers, painters/ gilders, upholsterers/paperhangers, picture-frame makers, even Venetian blind makers. An appendix of this kind would have underscored one of book’s main points, the complex and increasingly specialized nature of Charleston’s cabinetmaking community.

However, the darkest lining in the silver cloud of this book was undoubtedly the death of the co-author, John Bivins, in August 2001. A swashbuckling figure in the American decorative arts, John was a consummate craftsman and scholar. During his career at MESDA, he served as the director of restoration and as the curator of crafts, and, later, as the director of publications, editing two journals, The Luminary and The Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, during a golden age of that museum’s institutional history. John was the author of numerous books and articles including those cited previously in this review, Long Rifles in North Carolina (1968), and The Moravian Potters in North Carolina (1972), which he also co-authored with Rauschenberg.

As a teacher, John inspired students to enter the museum field, and as a colleague, he shared his research and opinions generously. Perhaps the greatest tribute to John’s career will be how The Furniture of Charleston inspires future generations to advance the study of the topic he loved so well. For an example, one need only consult pages 102 to 113 of the first volume. Here, the authors illustrate two quintessential Charleston pieces, a mahogany desk-and-bookcase with cypress and a mahogany and mahogany veneer double chest with cypress and white pine secondary woods (see figs. 3 and 4) made between 1750 and 1765. Each bears the cipher “WA” stamped on the bottom of the lower cases. The ciphers are identical, and the authors predict that their discovery will lead to an eventual attribution to the cabinetmaker William Axson (ca. 1739–1800), based on “matching marks” seen on the brickwork at Pompion Hill and St. Stephen’s churches, where Axson is known to have worked, and as “he was the only Charleston cabinetmaker with those initials that was active in the 1750s and 1760s” capable of producing such stylish wares. However, Rauschenberg and Bivins conclude that:

Linking these two pieces to the same shop and thus further linking the other eight or nine pieces in this group to Axson is tempting, but impossible to positively attribute without further research on this topic—research that is impossible for the authors to perform with the discovery of the mark on the double chest coming so close to deadlines for this publication. The marks and their relationship to furniture and cabinetmakers must be left for future researchers to investigate (pp. 102–3).

Which American furniture student is now prepared to accept the authors’ challenge? By completing such a comprehensive encyclopedia of Charleston furniture, Brad Rauschenberg and John Bivins have guaranteed that questions such as these will occupy the minds of America’s furniture scholars, collectors, and dealers for decades to come.

Robert A. Leath

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

J. Thomas Savage, “The Holmes-Edwards Library Bookacse and the Origins of the German School in Pre-Revolutionary Charleston” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Founation, 1997), p.107.