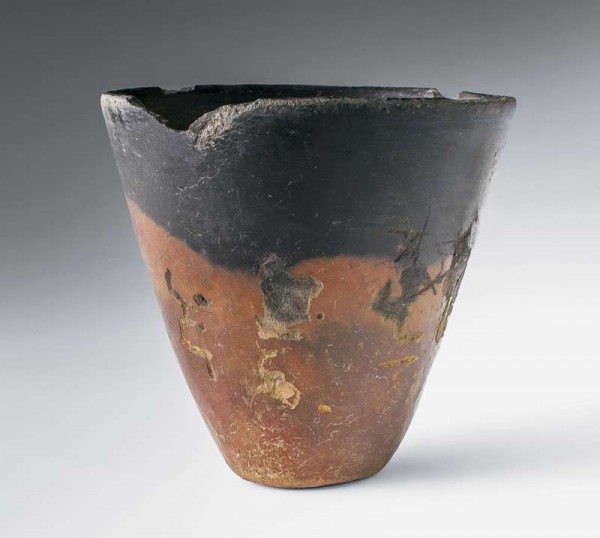

Beaker, Egypt, post-4000 B.C. Earthenware. H. 3 7/8". (All objects from the author’s collection unless otherwise noted; photo, Robert Hunter.) The decoration is the result of both oxidization and reduction in the firing. The incised graffito is of Coptic origin, ca. 500 B.C.

Naturally mummified adult male, alongside Badarian-style beakers, reputedly Gebelein, Egypt, Predynastic period, ca. 3500 B.C. L. 64 1/8". (© Trustees of the British Museum.) The mummy is often referred to by the name Ginger, referencing the tufts of ginger-colored hair on its scalp.

Beakers, Upchurch, England, 1st century A.D. Burnished gray-bodied earthenware. H. 6 5/8" (left) and 5" (right). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These “Upchurch ware” vessels were recovered together from the Medway Marshes.

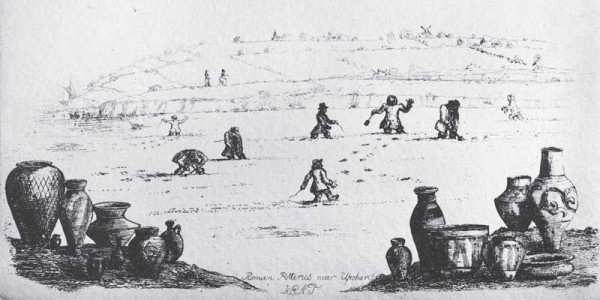

Untitled engraving, England, ca. 1870. Local antiquaries sent servants into the mud in search of Upchurch pots while they picnicked on the high ground.

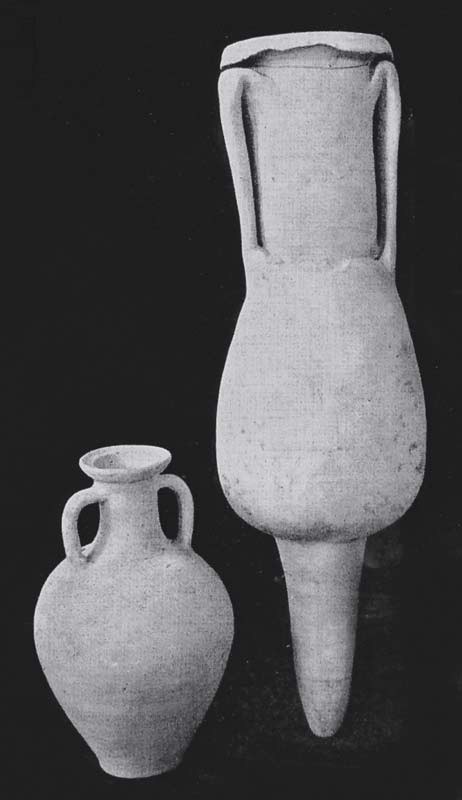

Amphora, Roman, 1st century A.D. Unglazed earthenware. H. 38". (Courtesy, Museum of London Archaeology.) The amphora is flanked by a wine jar, both excavated in London in 1950.

Roman amphora and wine jar illustrated in fig. 5 as first uncovered in the 1950 archaeological excavation, after having been smashed during the sacking of Londinium in A.D. 61. (Courtesy, Museum of London Archaeology.)

Dish, attributed to Martin’s Hundred potter Thomas Ward (act. ca. 1620–1635), James City County, Virginia, dated 1631. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 10 7/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Fragments of a cup, London, England, ca. 1665. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Photo, Ivor Noël Hume.) The fragments, excavated from a 1666 deposit at the London Sergeants’ Inn, are shown here with a reproduction cup (H. 5") made by potter Michelle Erickson.

Cruet fragments with pewter thumbpiece, France, ca. 1760. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. approx. 4 1/2". (Courtesy, E. B. Tucker Collection; photo, Ivor Noël Hume.) The fragments were recovered from the ca. 1760 wreck of a French ship off the coast of Bermuda.

Cruet with pewter thumbpiece, France, ca. 1760. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 4 1/2". (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

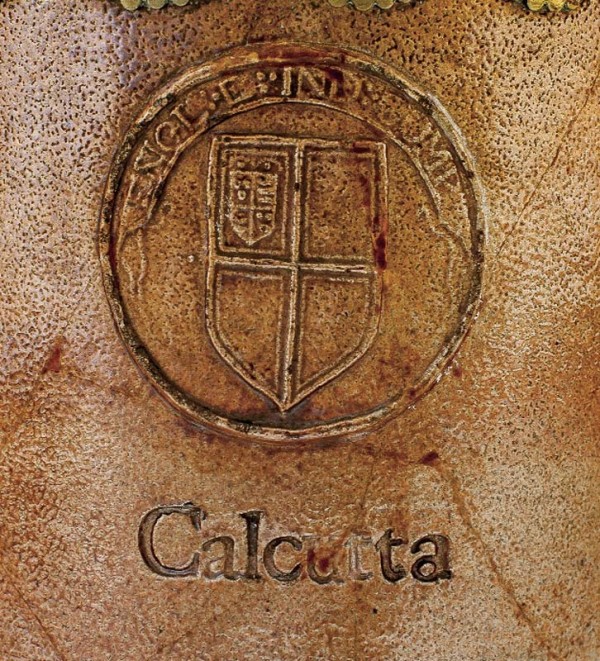

Tankard with original brass mount, England, ca. 1758. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/4". Marks: impressed armorial badge of the East India Company; type-impressed “CALCUTTA” (Photos, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the armorial badge on the tankard illustrated in fig. 11.

Two-handled cup, William Cripps, London, England, 1761–1762. Silver. H. 18 1/8". (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.)

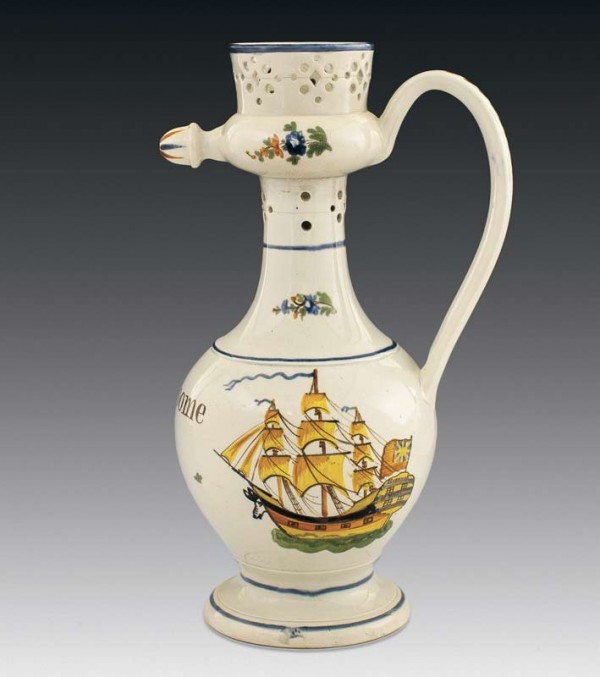

Puzzle jug, probably South Yorkshire, England, ca. 1795. Pearlware. H. 11". (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

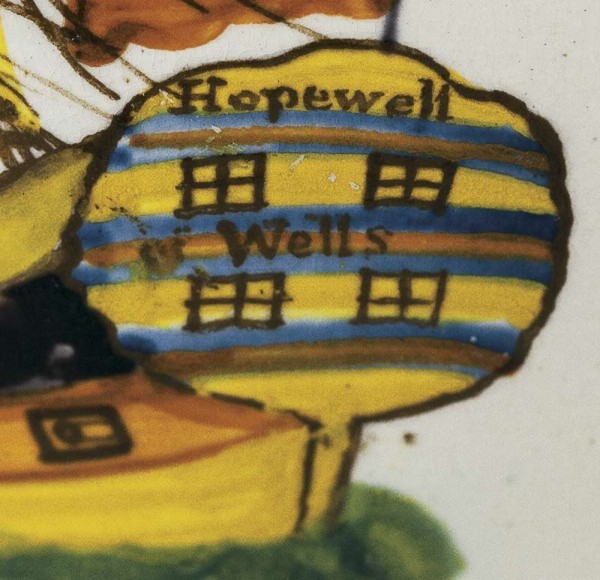

Detail of the ship Hopewell on the puzzle jug illustrated in fig. 14.

Detail of the stern showing the name Wells and the pierced heart on the puzzle jug illustrated in fig. 14.

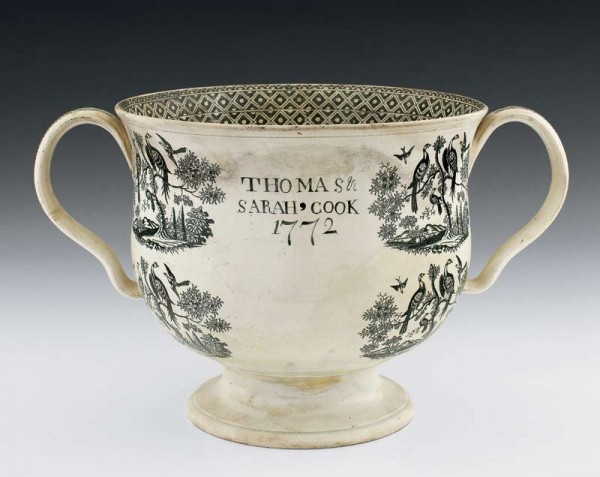

Loving cup, England, ca. 1805. Pearlware. H. 8 5/8". (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the central print inside the loving cup illustrated in fig. 17.

Coffee pot and saucer, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1805–1810. H. of coffee pot 10". (Photo, Robert Hunter.) The coffee pot has the The Archery Lesson print while the saucer design is known as “The Three Graces.”

Flask in the shape of a pistol, Joseph Bourne, Denby Pottery, Derbyshire, England, ca. 1845. Salt-glazed stoneware. L. 9 7/8". (Photo, Ivor Noël Hume.)

When wearing my archaeological hat I often was asked to name my most exciting discovery, and I invariably answered “the last one.” That response may sound both evasive and trite, but it happens to be the truth. I have tried to explain that archaeology is less about finding than finding out. It makes no difference whether the discovery is a rare gold coin or a common potsherd; each belonged to someone and its loss or being thrown away had an impact on a life. Losing the coin might have robbed a gambler of his ability to repay a debt, while reducing a plate to sherds may have led to welts on a serving wench’s back. In short, this is what I call “people stuff,” and I have been privileged to reach out across time to touch the things that once belonged to someone.

It is the same with my ceramic collecting. I have never yearned for the biggest or the best of anything, and price was dictated only by the depth of my pocket. Unlike philatelists, who strive to fill spaces in their albums, possessing all the variants of any one object has been my goal only if attaining them revealed something hitherto unknown. My aim has been to reach beyond the pots to the potters and owners. Thus the pots lead to documentary research and the thrill of delving into the written past. I was tempted to use the word history, but history lies dead on its pages. Holding a ceramic object, on the other hand, is an actual piece of the past. Somebody way back then held it, used it, talked about it, and the memories of that life are locked in the clay.

Many a museum curator will dismiss such an approach as unprofessional nonsense, but I suggest that there is a philosophical difference between many curators and collectors. A collector thoughtfully acquires something because he or she really likes it and is prepared to pay for it. Curators may be hired to care for a collection for which they have no personal affinity; consequently, new acquisitions might be sought for their rarity rather than a desire to put them in their historical context. Buying, say, a Wedgwood Portland Vase can be an exercise in museological one-upmanship leading to its Tiffany-lit exhibition with never a thought to showing it alongside a spread of Josiah’s bread-and-butter wares.

There is no Portland Vase in my collection, but I would argue that my chosen ten are of equal interest. They run an eccentric gamut from first-century Roman earthenware to an American nineteenth-century stoneware ginger-beer bottle. Their acquisitions always were motivated by interests aroused by my archaeological career, which began in the mud of a windswept Dickensian marsh in southern England and ended on the immaculate streets of Virginia’s restored Williamsburg. I make no apologies, therefore, for choosing unattractive and worthless fragments of a shattered and charred delftware mug as one of my chosen ten.

I am cheating, I confess, by including one object that I found but is now in the Museum of London’s collection. A second now belongs to the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. I have chosen them because they recall great ceramic moments in my archaeological career, and not least because each has a “people stuff” story to tell.

I. The El-Badari Beaker

In 1650 James Usher, archbishop of Armagh, informed anyone who could read Latin that the world was created in 4004 B.C. This redware beaker could, therefore, have been made at what poets call the dawn of time (fig. 1). The pot is in the style of Egypt’s prehistoric Badarian culture, which began circa 4000 B.C. Although a rather shoddy example, it has a good deal to say, both about the art of potting and about much later Egyptian history.

But first the potting lesson. Here is a classic demonstration of clay fired in both an oxidizing and a reducing atmosphere. Made without a wheel or a kiln, it was baked upside down in an open fire. The mouth, being deep in the ashes, emerged black, whereas the lower body, exposed to the air, burned red.

I was on my second journey up the Nile to take photographs for a lecture I was to give to the National Geographic Society that I titled “Gods, Graves, and Graffiti.” On my first trip I had been appalled by the deliberate damage done to the monuments by previous travelers, from ancient Greeks to Soviet Russians. So it was that while recording the names of the miscreants I wound up in Luxor after a hot day in the Valley of Kings. An antiquities dealer with a shop below the Winter Palace Hotel talked about his trade while we sipped his glasses of hot tea. Antiquity dealers are very hospitable.

Most of what he was selling came, he said, from the village of Gournou, which stands atop the tombs of Egypt’s lesser folk who had provided a long supply of chopped-up sarcophagi and assorted grave goods (fig. 2). But all good things come to an end, said my friend, and when they did, the inhabitants of the village became skilled in manufacturing new ones. “But this,” he said, handing me the Badarian beaker, “this one, he okay.” And it clearly was.[1]

Scratched deep into one side was a crudely incised inscription put there by a Coptic Christian who had dug it up, used it, and scarred it. His were the same people of the fifth to the seventh century B.C. whose insistence that there could be no god but theirs had led to defacing any deity they could reach without a ladder. Thus, the vandalism that I had come to photograph could now come home with me on a perhaps four-thousand-year-old pot as a lasting reminder that in Egypt religious zeal is no respecter of other people’s past.

II. The Best Beaker

To determine the most prized object in one’s collection, the simple answer is to see which one you are cradling when a hurricane strikes. For me it is always these paper-thin, burnished gray beakers that came to be mine by virtue of treading on them in the mud of the Medway Marshes (fig. 3).

In the mid-nineteenth century Kentish antiquaries came upon the remains of extensive Roman-period pottery manufacturing on these riverside marshes (fig. 4). Eighteen hundred years ago the marshes were low-lying dry land and supported a Staffordshire-like ceramic industry. While a novice archaeologist working in London, I frequently came across pottery that books called “Upchurch ware” and dated to the first and second centuries A.D. The quality of the potting and the shapes of the wares were so diverse, however, that it was hard to believe that they came from the same source. Audrey, my archaeologist wife, and I decided to follow the Victorians and look for ourselves. Where once there had been land, at low tide acres of gray mud stretched as far as the eye could see. Ribboning through it were narrow causeways flanked by what appeared to be a shoreline of water-washed pebbles. On closer inspection they turned out to be myriad Upchurch potsherds that were washing out of the causeways.[2] The erosion had been going on for centuries, leaving pottery buried in pits below the mud’s surface. But there were other hidden pits, left by the area’s usage as a World War II bombing range, into which an unwary step could be fatal.

The beaker’s pit (if, indeed, it was a pit) was shallow, and my heavy-booted foot ceased sinking when it rested on the most splendid, unbroken examples of Upchurch’s best I was ever likely see.[3]

III. The Walbrook Amphora

Cups and dishes are well known as household projectiles, but it is rare to find anything this large being used as a weapon of destruction. I found the 38-inch Roman wine jar on a London construction site in January 1950 (fig. 5). The type was not unique but, being unbroken, it attracted national media attention, but it was not the jar but its moment in British history that resonated.[4]

I could pin the date to A.D. 61, when the East Anglian tribe of the Iceni rose against their Roman conquerors. Led by Queen Boudicca, an army of Britons burned the Roman towns of Verulamium (St. Albans) and Camulodunum (Colchester) on their way to destroy Londinium. Once there they raped, slaughtered, sacked, and burned the city. In one looted home they took sixteen earthen pots from a kitchen and threw them into an open trash pit. To make sure that they were smashed, the invader hurled the amphora down on top of them, causing the fragments to erupt around it (fig. 6). Then, to complete the job, a large two-handled ewer landed on the wine jar, cracking the amphora’s upper handle. The force of the contact broke the neck off the ewer, which landed on one side and the body on the other. I was staring into the face of Vengeance, of wanton destruction not unlike the carnage unleashed by Germany that had left this site in ruins 1,879 years later. Never, to my knowledge, has a ceramic object so forcefully marked its place in history.[5]

IV. Take Two!

When filming, it is always best to get it right the first time, particularly if one is both the writer and the on-camera narrator. Consequently, the discovery of my third selection carried with it a never-to-be-forgotten cinematic embarrassment. It happened like this: I was excavating on an archaeological site we believed to be the home of one of Virginia’s earliest potters, John Jackson, who had been among the first settlers at the plantation known as Martin’s Hundred. He had been at work there before 1622, when Indians, who preferred not to be colonized, attacked the farms and fort and killed more than fifty of the settlers. Jackson was among the survivors who picked up the pieces and tried again.

Encouraged and funded by the National Geographic Society, we made a warts-and-all but ultimately prize-winning television chronicle of the excavation and our interpretation of what we were finding. One morning, deep in the woods, I was excavating in an artifact-filled pit and explaining to the camera that we could determine the date of the filling by an analysis of its clay tobacco-pipe fragments. Their message, I said, was 1619, the year that Martin’s Hundred began to be settled. “In this pit, this very pit, we are uncovering the beginning of potting history in America,” I declared while exposing the edges of a slip-decorated earthenware dish.

Seemingly on cue, a shaft of sunlight speared through the trees onto the dish to highlight the date that the potter had slipped onto it. In large yellow digits it read “1631.” I forget my unnarrator-like response that prompted our director to shout “Cut!” Yet even though everything I had been saying about tobacco-pipe dating was proved wrong, I was half right about the dish. Elaborately decorated with a spread-winged bird, in a style that a decade later in England would be called Metropolitan slipware, it was, and remains, the earliest dated example of American slipware (fig. 7).[6]

V. London’s Burning!

Urban archaeologists, by training, tend to look down. I was doing so one 1952 day at London’s Sergeants’ Inn, where utility workers were digging a sidewalk trench. The dirt thrown up from it was interestingly dark, and in it lay the reason why: burned and warped fragments of window glass, a cupboard hinge, pieces of a scorched delftware mug (fig. 8), and a couple of readily datable tobacco pipes. The workers were digging through the debris of the great fire that destroyed London in 1666.

Being beyond London’s walled square mile, I had no authority to stop the digging or even to get down into the trench. All I could do was salvage fragments from the top of the dirt pile. I have them still, all carefully wrapped in newspaper advertising the songs of Elvis Presley and a 1937 Bentley for £400 (£100 deposit)—social history old and new together in a box.

The fire started on September 2, and when Sir Thomas Bludworth, the Lord Mayor, was told about it, he dismissed it, saying “Pish! A woman might piss it out!”[7] Four days later his city was in ashes, 13,200 houses and 87 churches burned, and virtually its entire population had become homeless. The flames that had broken out near London Bridge were stopped short of the Tower, but spread westward down Ludgate Hill, jumped the Fleet River, and headed up Fleet Street to Sergeants’ Inn, where I was now standing. Beyond, in the fire’s path, lay the historic church of the Knights Templar, which was saved by blowing up the houses around it.

Holding up my fragments of window glass I could imagine the eyes of the last person to peer through it as the flames drew nearer. It turned out that I was not the first to salvage such a souvenir. On September 5, 1666, diarist Samuel Pepys, picking his way home through the still-smoldering ruins, “took up (which I keep by me) a piece of glass of Mercer’s chapel in the street, where much more was, so melted and buckled with the heat of the fire, like parchment.”

Like Pepys, I have kept these fragments by me across half a century, a continuing reminder that a scorched and shattered delftware mug (like the one Michelle Erikson reproduced for me) can bring one within a hand’s touch of history.

And for me, that is what collecting is all about.

VI. The French Connection

In 1908 the wise Water Rat in Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows told Mr. Mole that “there is nothing—absolutely nothing—half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats.” The words were barely out of his mouth when the boat grounded. In this disaster all hands (or, rather, feet) scrambled safely ashore. It was rarely so.

I was reminded of another shipwreck while hunting for treasures, not underwater but on a wet day in London’s Portobello antiques market. In a stall beneath a dripping canvas roof stood a small faience pitcher whose twin I had seen in fragments among hundreds spread out on a Bermuda veranda (fig. 9). It was a French cruet bottle, elegantly pedestal-based and nearly swan-necked, and polychrome-decorated with a sprig of flowers and a girth girdle in blue and red. Its faience lid was decorated with radiating lozenges using the same palette and secured with a pewter thumb plate, a mount identical to that of the Bermuda fragments (fig. 10).[8]

In the course of my longish life there have been several “why me?” occasions, and this was one of them. Why should I have been the one chosen to reassemble the shipwreck fragments and why should it have been me who had bothered to peer under the dripping canvas to find their mate?

The wreck was excavated by famed Bermudian diver Teddy Tucker who, though reviled as a treasure hunter, had carefully salvaged every tiny ceramic fragment from the ship we know only as “the French wreck.” No gold or silver repaid the divers for their efforts, but among the complete ceramics was a gourd-shaped faience bottle, polychrome-decorated with a pair of dueling Chinamen and inscribed “La Violeta 1749,” thus providing a date after which the cruet bottle put to sea.

Although fitted with at least a dozen cannon of six-pound caliber, this was a merchant ship sailing north from the Caribbean, where it had picked up a cargo of lignum vitae. The presence also of crates of rusted muskets and cutlasses suggested that she was on her way to Louisbourg or Quebec during France’s Seven Years’ War with England. Indeed, her captain may never have intended to go anywhere near British Bermuda and its treacherous reefs.

There is no denying that nothing is half so much fun as messing about in boats that sank, but this one provided a time capsule of mid-eighteenth-century French ceramics unparalleled even in France.

VII. Heroes on the Hugli

The Seven Years’ War that had taken a French cruet to Bermuda took another ceramic treasure to India and into the 1759 Battle of the Hugli River. But that is not where my story begins. It starts at a Williamsburg Antiques Forum in 1963 or thereabouts. In those far-offdays, attendees with mink coats and money threw competing cocktail parties to which anybody who was anybody was quietly invited. Although these were social events at which it was unseemly to do business, up-market dealers would discreetly mention that they had something exciting to offer. One of them was Rupert Gentle, a renowned specialist in brass, who showed me a photograph of a large English brown stoneware mug with “CALCUTTA” type-impressed on its front and its rim concealed under a decorative brass collar (fig. 11).

“Isn’t it odd,” he said, “that they would put the name of an Indian town on an English mug?” I suggested that as the front also included an armorial badge under the wording “Eng*E*Ind*Comp” (fig. 12), one could deduce that Calcutta was the name of a company ship. “Of course!” Gentle replied. Would I be interested in buying it? I would indeed, but the mug had been broken and very badly restored, and his price was way beyond my budget. Nevertheless, as my enthusiasm for English stoneware burgeoned, I repeatedly kicked myself for having allowed that seemingly unique relic of the East India Company to escape. Worse, I had given Gentle information that could enable him to boost his price even higher.

Ten years later, in London’s Brompton Road, antique dealer and friend Alastair Sampson told me that he had something that might appeal to me. It was an English stoneware mug with the name of an Indian town on it—which he thought was odd. Odd, indeed; but so was the fact that Alastair was pointing to Rupert Gentle’s CALCUTTA mug. It had shed my information but had been very well re-restored and could now be mine at half his price. It would not escape again.

The mug has an unhelpful “WR” excise stamp below its rim, but there was no doubt from its style that it could be attributed to the mid-eighteenth century. In all likelihood it was ordered by the East India Company in 1758, when the Calcutta was commissioned. The ornamental brass rim also suggested that the mug was intended for sea service.

The ship was built on behalf of the company at the Wells family’s Rotherhithe shipyard.[9] She was a 632-ton three decker with mounted 26/30 guns; she had a crew of ninety-nine. Her captain, George Wilson, was part owner; Pitt Collett signed on as first mate. Together, they sailed from Portsmouth on February 15, 1759, and reached the Hugli River on November 19.

The Hugli is a branch of the Ganges, and in 1690 the British had founded the town of Calcutta on it. Thenceforth its garrison was skirmishing with the French and Bengal’s successive Nawabs. After Calcutta had been lost in 1755 and retrieved a year later, the Dutch decided to take advantage of the battle-weary British and sent six 36-gun ships and 1,500 soldiers to see what they could grab.

Only three East India merchant ships stood between the invaders and the city. They were the Duke of Dorset, the Hardwicke, and Captain Wilson’s Calcutta. On November 24, drawn up in line of battle, the three East Indiamen awaited the arrival of the Dutch fleet. When the fleet came in range, the battle was brief. The Dutch commodore struck his colors; four more surrendered, and a sole warship escaped, only to be captured later by two arriving company merchantmen.[10]

One would like to claim that the Calcutta’s mug reverberated to the roar of her guns, and that on the day of the battle Captain Wilson had his fist around its handle. But such romantic notions aside, the 1758 tankard may be the only surviving ceramic memorial to the drama played out that November day on the Hugli River. However, it is not the sole relic of the battle. London’s National Maritime Museum has a silver cup (fig. 13) given to the Duke of Dorset’s first mate, John Allen, who took command when the captain, Bernard Forrester, was fatally wounded. In 1762, after returning safely to England, Captain Allen received both the silver cup and a 50-guinea bonus from the company, whose gratitude and generosity extended also to the three ships, each receiving £2,000.[11]

There may be no record that the little fleet’s commander, Captain Wilson, received a silver cup, but his memory endures in the Calcutta’s stoneware mug.

VIII. A Fool and His Money?

Buying is not the same thing as collecting, particularly if you intend to buy only one—as I explained to my wife when I set out to buy John Bloome’s puzzle jug (fig. 14). It had turned up in the catalogue of dealer Jonathan Horne, but by the time I saw it he had taken it to New York to an antiques fair. He undoubtedly expected it to be quickly and advantageously sold. It turned out, however, that it was still sitting on his stand when the show ended. Perhaps the would-be buyers saw it as they would a loving cup that had lost its handles, a poor thing unworthy of a collector’s cabinet. John Bloome’s pearlware jug had only one spout.

The whole arcane idea was that puzzle jugs had a sufficient number of spouts to be puzzling. The majority had three and a few as many as six; so why was Bloome’s jug made with only one? The question may have been of no concern to the New York fairgoers, but to me it stood out as a mystery that had to have an answer.

The jug was safely out of reach and on its way home to England when I bought it—still unseen. It was several weeks, therefore, before I had it in my hands. Despite its paucity of spouts, the jug was an extremely elegant example of the potter’s art. It was painted in colors often associated with so-called Pratt Ware and dated 1795–1805. John Bloome’s name was boldly spelled out, accompanied on one side by a delicate strewing of blossoms (I hesitate to say blooms) and on the other with an eight-gun ship in full sail, a merchant fleet’s red ensign at her stern and under it her name, Hopewell (fig. 15). Under it there is more, an arrow-pierced heart and, to its right, the name Wells (fig. 16). Could the ship have been built by the Wells brothers in their East India Company yard?

On advancing from stern to bow, however, one finds a device as puzzling as a dearth of spouts. Where a mermaid, lion, or some other uplifting icon should provide the gilded figurehead, the Hopewell sported a gray and carefully painted jackass.

Readers may think up a different explanation, but here is mine:

John Bloome squandered his fortune on a failed enterprise involving the Hopewell and her cargo. His distraught and furious wife voiced her opinion by ordering him a puzzle jug so simple that even a jackass could figure it out.

But what about the pierced heart? Could Mrs. Bloome have been in love with Captain Wells?

If these pots could talk is a wish of many a collector. But few can speak as loudly as this jug does of the voices raised on the day that John Bloome unwrapped his gift.

IX. If It’s Dated

...it has to be worth a lot more! That adage comes readily to the tongue of every antiques dealer. It not only excites the collector, it also hides any ignorance or doubts in the mind of the seller. Both are aware that in ceramic studies, the dated pieces are the cornerstones of comparative research. They bring back into the fold many a lost lamb whose age has hitherto been in doubt. Thus, when we risk bidding at an auction on the bowl that is described but not illustrated, we can have confidence that the auction house cataloger is not mistaken. Dates don’t lie.

Or do they?

When I started writing about pearlware back in the early 1960s, it was looked upon as cheap creamware’s poor relation and could be bought for a short song. Unfortunately, my series of articles in Antiques magazine soon elevated it to levels above my range. Nevertheless, now and again a piece came up at Sotheby’s that I could not allow to escape. One of them was a large pearlware loving cup, transfer-printed and hand-inscribed in black “Thomas & / Sarah Cook / 1772” (fig. 17).

For the benefit of colonial archaeology students, I should note that it is sometimes hard to distinguish pearlware from the whiter creamwares. The difference most readily shows itself by glaze piled up inside footrings where creamware appears greenish yellow and pearlware blue. The latter became popular in the 1780s and stayed common into the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Thus, when in archaeological contexts, it was safe to assume that the deposit was post-colonial—until the Cook loving cup turned up in London.

In 1779 Josiah Wedgwood named his whitened creamware “Pearl White,” and though he did not see it as a worthy successor to the yellow ware, other factories did. By 1787 eight Burslem factories were producing what they called “china glaze” blue painted or transfer printed. I had noted that this “was of considerable importance in that it shows that transfer-printing on ‘china glaze’ or ‘pearlware’ had begun by 1787.”[12]

Here, therefore, was a groundbreaking discovery—the Cook loving cup was saying that it was made seven years before Wedgwood named it, and seventeen before it was in general production. Being in Williamsburg while the sale was in London, I asked dealer friend and stoneware expert John May to go to Sotheby’s and look to be sure that it really was pearlware and, if it was, to bid on it. Yes, came his answer, the blue was there, but so also was a bad crack. I told him that the crack didn’t count; it was the message that mattered.

Two months later the cup arrived and it proved to be exactly as described. It also had a pair of unusual but pleasing ear-shaped handles and was decorated with transfer-printed birds that looked like pheasants. The game-hunting theme carried over to the inside, where the central print showed two women practicing archery—which was where my jaw dropped.

The print, usually called The Toxophilites or The Archery Lesson, was designed by Thomas Turner circa 1794 and showed three female archers separated by their tutor (fig. 18).[13] Ralph Wedgwood bunched them up and hid all but the tutor’s head, a design in his pattern book put together before 1801.[14] A related pattern depicting the Three Graces became popular at the time of the Treaty of Amiens in 1805, and that, alas, has to be the approximate date of the loving cup (fig. 19). As for the Cooks and their 1772 date, perhaps it recalls their thirty-third wedding anniversary.[15] True or not, the pearlware cup is a constant reminder that although dates rarely lie, they certainly can mislead.

X. Stand and Deliver!

Eighteenth-century travelers cringed at the sound of that order, and so did I. But the voice was not that of a highwayman but of a security officer at Heathrow Airport. I tried to explain to him that the pistol in my carry-on bag was no threat to anyone.

“You should know, sir, that no weapons are allowed onboard,” he replied in a tone that brooked no argument.

“But it’s not a weapon, it’s....”

“It looks like a weapon to me, sir.”

“... it’s stoneware. It is only pottery!”

“It’ll be returned to you when you get to New York.”

I watched him drop it into a paper sack, but too late to remind him that the pistol was a fragile antique more than a hundred years old (fig. 20).

While we were coming in to land, our stewardess came down the aisle carrying two paper sacks. “You’re Mr. Hume, right? This one is yours,” she smiled. “All safe and sound.”

She had departed toward the rear of the aircraft when I opened my sack and found that its pistol was not by Bourne of Derbyshire but by Smith & Wesson of Springfield, Massachusetts. The mistake was quickly rectified, but I have often wondered who had surrendered the .38 Special and what might have happened later if neither of us had opened our sacks.

The security man had been right—up to a point. The stoneware pistol by Joseph Bourne of the Denby Pottery does look realistic, more so than the several others made by London’s Doulton and Watts (1815–1858), Stephen Green (1831–1858), or S. & H. Bridden of Brampton, Derbyshire (ca. 1848–ca. 1860).[16] Just as firearm technology advanced from flintlock guns to the use of percussion caps, so did the potters’ model makers. But even while moving with the times, the stoneware pistols were pretty clunky and unlikely to deceive. But who, if anyone, were they supposed to scare into standing and delivering?

On a dark night in the narrow alleys of London’s East End slums, drunken topers staggering home might be intimidated if they saw only the muzzles, yet it is unlikely that they would have sufficient pennies left to be worth robbing. The pistols are an enigmatic and minor element in the collecting field collectively known as “spirit flasks.” Beginning about 1830, London and other potteries began making molded, brown stoneware bottles in the shape of political heroes and their causes, most relating to the surge toward parliamentary reform, such as portraits of Lords Brougham, Grey, and Russell—as well as King William IV, who was seen as the figurehead of the bad guy, no reformers. By 1836, when the matter had been resolved (after a fashion), the flask makers turned their attention to the coronation of Queen Victoria and then to subjects of general amusement, like polka dancing and cartoon characters. About 1840 the flask molders turned their attention to their customers. The genre died circa 1856, when the Crimean War provided the modelers with their last great marketing idea.

Somewhere in that post-coronation category emerged the ceramic pocket pistols. (The term originated long before potters got the idea.) Thus, as early as 1730, one Edward Burt wrote, “I have always on my journeys a pocket-pistol loaded with Brandy mixed with juice of lemon.” The name continued in use long enough to find a place in The Slang Dictionary (London, 1865), in which it was defined as “a dram flask.” Ignoring the question of whether by then the flask still looked like a gun, it is reasonable to suppose that selling gin in a stoneware pistol had been a reasonably successful marketing ploy.

In an era long ago and far away (1927 London) IVOR NOËL HUME was born with a silver spoon in his mouth. It was snatched away in the Wall Street crash, foretelling a life dappled with ups and downs. An artistic child, he was taught to be a ceramist in kindergarten. He made a gift for his mother, who received it with “Good God, what’s that?” He told her that it was a pottery pea pod. Thereafter his creative drive took other directions, such as adding beards to schoolbook illustrations and making gunpowder as a step toward building fireworks that only went sideways. His academic years lacked brilliance, as did his World War II career as a volunteer for the Indian Army that ended without a day in Delhi. Four subsequent years in the magical world of the theater ended with a stint as the Demon King in a haunted pavilion in Cornwall, followed by a Dickensian role as a Thames River mudlark. He was saved from starvation by the curator of London’s Guildhall Museum, and in 1949 he found himself the museum’s sole employee and responsible for the City of London’s postwar archaeological salvage. He was twenty-two years old, as was Audrey Baines, who had a degree in archaeology and risked marrying him. Together they immigrated to Virginia and made new careers as archaeologists for Colonial Williamsburg, which, since 1930, consisted of spade-digging without understanding what a trowel could do. After thirty-five years demonstrating the trowel technique, they found themselves in a limousine bound for Buckingham Palace and a word of encouragement from their queen. Audrey died a year later. He remarried and continued a literary career that included Chipstone’s If These Pots Could Talk. He is still writing, albeit more slowly.

World Ceramics: An Illustrated History, edited by Robert J. Charleston (1968; New York: Crescent Books, 1981), p. 24.

Ivor Noël Hume, “Romano-British Potteries on the Upchurch Marshes,” Archaeologia Cantiana 68 (1954): 72–90.

Ivor Noël Hume, All the Best Rubbish (New York: Harper & Row, 1974), pp. 134–35.

Ivor Noël Hume and Audrey Noël Hume, “A Mid-First Century Pit near Walbrook,” Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society 11, pt. 3 (1952): 249–58.

Ivor Noël Hume, Discoveries on Walbrook, 1949–50 (London: Guildhall Museum, 1950), pl. VI.

Ivor Noël Hume, Martin’s Hundred (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1979), pp. 126–29.

Neil Hanson, The Great Fire of London: In That Apocalyptic Year, 1666 (Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, 2001), p. 49.

Ivor Noël Hume, Shipwreck! History of the Bermuda Reefs (Hamilton, Bermuda: Capstan Publications, 1995), pp. 20–24.

The East India Company’s main shipyard was across the river at Blackwall and had been since circa 1600. It was bought by John and William Wells in 1788. I am deeply indebted to Rosalind Martin and the British Library for this and much other related information.

Sir Evan Cotton, East Indiamen: The East India Company’s Maritime Service, edited by Sir Charles Fawcett (London: Batchworth Press, 1949), pp. 155–56.

I am greatly indebted to Angelika Kuettner, who recognized the relevance of the National Maritime Museum’s covered cup (coll. no. PLT0003).

Ivor Noël Hume, A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America (New York: Knopf, 1972), p. 128.

Geoffrey A. Godden, British Pottery and Porcelain, 1780–1850 (New York: A. S. Barnes, 1964), p. 38.

Minnie Holdaway, “The Wares of Ralph Wedgwood,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 12, no. 3 (1986): 255-64, pl. 162a.

If one pushes the cup back into the 1790s, their twenty-fifth anniversary would have been in 1797

Ivor Noël Hume and Lance Mytton, Gin: Legacy of the Doomed (Shrewsbury, Eng.: Curiosus Press, 2013), p. 27, and p. 91, no. 37