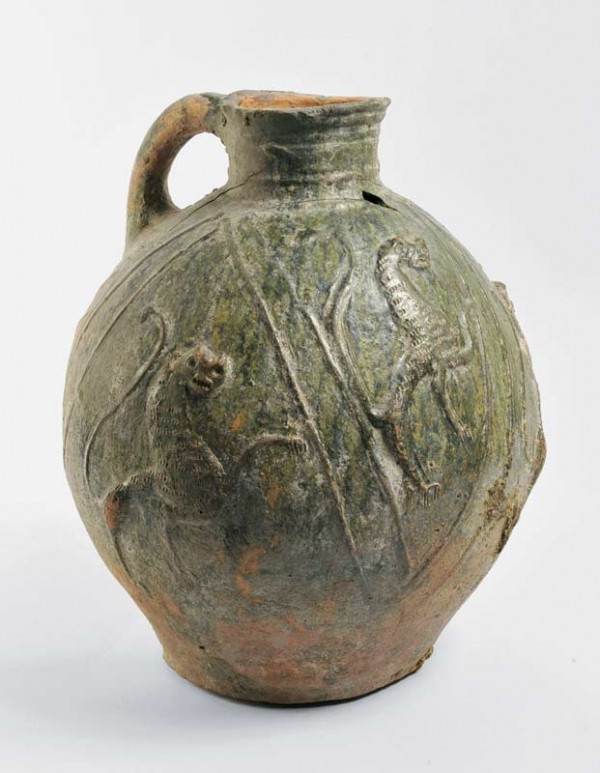

Jug, London, England, 13th century. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 15 5/16". (Courtesy, Museum of London.) This London-type ware jug with zoomorphic decoration was found in the City of London.

Detail of one of the applied beasts on the jug illustrated in fig. 1.

Group of vessels, Surrey-Hampshire border, England, late 16th century. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. of dish 8 13/16". (Courtesy, Museum of London; photo, Edwin Baker.)

Schweinetopf (lit. “pig pot”; casserole), Surrey-Hampshire border, England, late 16th century. Lead-glazed earthenware. L. 10 13/16". (Courtesy, Museum of London, 69.12/1; photo, Torla Evans.)

Bartmann jug, Cologne, Germany, ca. 1550. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7 5/16". (Courtesy, Museum of London, A10986.)

Bartmann jug fragment, Cologne, Germany, ca. 1550. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Museum of London.) Found on the site of 12–26 Magdalen Street, Southwark (MGS96).

Dish, Aldgate pothouse, London, England, dated 1600. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 10 3/16". (Courtesy, Museum of London, C84.)

Fragments of biscuit delft, probably made at the Aldgate pothouse, London, England, late 16th century. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. of wet drug/syrup jar 9". (Courtesy, Museum of London; site code HTP79 context [220].)

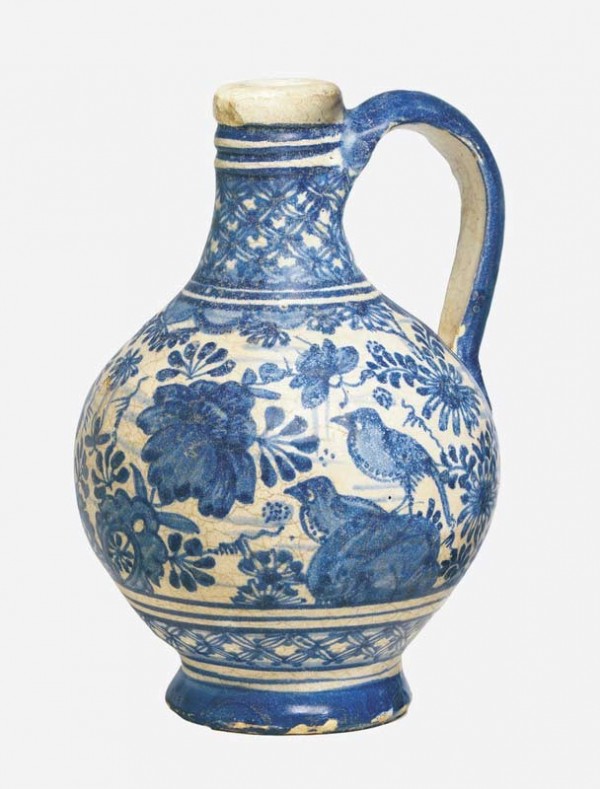

Bottle, Pickleherring, Southwark, London, dated 1627 (possibly 1628). H. 7 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of London; site code PLQ95 context [121].) Note the Bird on Rock decoration.

Plate, Pickleherring, Southwark, London, England, 1625–1630. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 7". (Courtesy, Museum of London, 24368.)

Dish, Harlow, Essex, England, dated 1632. Metropolitan slipware. D. 13 7/16". (Courtesy, Museum of London; site code CEH12, context [105]; photo, Andy Chopping.) This dish was found in London.

Dish, Italy, early 17th century. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 6 11/16". (Courtesy, Museum of London; photo, Andy Chopping.) This polychrome maiolica plate decorated in stile calligrafico naturalistico was recovered from excavations at 1–2 Albion Place, London EC1 (site code ABP94, context [469]).

Dish, Southwark, London, England, late 17th century. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 14 5/8". (Courtesy, Museum of London; photo, Andy Chopping.) This charger was recovered from excavations at Chaucer House, Tabard Street, Southwark, London (site code CH75, context [17]).

Plate, London, England, early 18th century. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 11/16". (Courtesy, Museum of London; photo, Andy Chopping.) This rare plate with a Hebrew inscription was recovered from excavations at 12–14 Mitre Street, London (site code MIR84, context [100]).

Mug, Lowestoft, Suffolk, England, ca. 1760s. Soft-paste porcelain. D. 3 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of London; photo, Andy Chopping.)

After spending thirty-seven years studying thousands of individual pots and recording and analyzing millions of sherds of pottery, I confess the task of distilling this vast array of ceramics into ten objects initially seemed rather daunting. However, the challenge of highlighting representative key items made over some twelve hundred years has also proved to be tremendously stimulating, with the final choices almost lining themselves up for selection.

All the vessels included here were found in London, and half of them were made in the London region. They range in date from the mid-thirteenth to the mid-eighteenth century, and they all come from the collection of the Museum of London or from archaeological excavations carried out by MOLA (Museum of London Archaeology) and its predecessors. These are pots that belonged to people living in London—they represent personal choices made from the very considerable range of ceramics available in one of the world’s great centers of international trade. Yet only two non-English pots have been included, emphasizing the largely local nature of ceramic supply before the rise of the Staffordshire Potteries changed the face of British ceramics forever.

Only one medieval vessel has been selected out of countless possibilities. This one magnificent pot must stand as representative for the ceramic industry of the London area, which flourished from the twelfth to the mid-fourteenth century. The industry played a significant role in wider regional developments through the dissemination of technology and stylistic influence. It was also the first ceramic industry of the London area that I studied in depth, as part of a series of corpora of London’s medieval pottery published between 1982 and 2010.

Two of my chosen pots date to the sixteenth century. One of these was made in the important pottery industry centered on the border between the counties of Surrey and Hampshire. As part of a project to analyze and publish the findings of excavations carried out under the auspices of Guildford Museum in 1968–1972, the vessel selected here played a major part in the identification of Rhenish influence in transforming the border ware industry during the later sixteenth century. My fourth choice takes us directly to the stoneware potteries of the Rhineland and the importance of Continental wares within London’s pottery supply.

Five of my selected pots date to the seventeenth century, a time of vibrant growth and innovation in the potteries serving the London area. Three of these are in London-made delftware, including the earliest known dated piece, one of the jewels in the Museum of London’s crown. The other delftware vessels selected were made in Southwark, where extensive excavation since the 1980s has uncovered vast quantities of ceramic wasters on numerous sites.

The two other seventeenth-century pots I have chosen were made outside London, one of them in the potteries of the Harlow area of Essex and the other in Italy. The magnificent large dish in Metropolitan slipware, excavated in 2013, is one of the earliest dated examples known from the Harlow kilns. Although much less complete, the colorful plate I discuss is a particularly unusual and delightful product of the influential Italian maiolica potteries.

Finally, there are two eighteenth-century vessels. The first of these was found on a site in East London and is the earliest known example of pottery made specifically for use by the Jewish community. My last pot, made in Lowestoft porcelain, was found on the site of a coaching inn in West London, forming part of an important clearance group deposited at the end of the century. I have included it simply because I love it!

Medieval Heraldic Beasts in Clay

This splendid jug (fig. 1) was recovered during excavations in 1987–1988 on a site in the City of London.[1] It was found, virtually complete, in the fill of a cesspit situated in the backyard of a property fronting onto Ludgate Hill. Unbroken vessels are relatively rare finds on heavily built-up city sites, and although the organic pit fill would have helped protect the pot, it remains a mystery why it was thrown away apparently intact and possibly still usable.

Jugs made in a great variety of shapes and sizes are one of the chief London-type forms found archaeologically. This large, rounded jug was made in London-type ware, the major ceramic industry that supplied the capital with everyday pottery from the end of the eleventh to the mid-fourteenth century.[2] The vessel has striking zoomorphic decoration of a kind that developed during the early to mid-thirteenth century.[3] A copper-stained green glaze was applied over a white slip covering the red-brown body, with plastic decoration added in red-firing clay.

The body of the jug is divided into four triangular panels by paired applied strips. Within each of these stands a large, ferocious-looking animal (fig. 2), modeled in relief in applied body clay. They rear erect in classic rampant posture, with the front left paw raised and the long, thin, tufted tail curling upward. The paws have deeply incised claws, and the heads are turned toward the onlooker, baring sharp teeth in a fearsome snarl. Although highly stylized, they have distinctly feline features, with short pointed ears and large saucer-like eyes. The body of each beast has been closely stabbed with a comb, presumably to represent fur.

A distinct tradition of zoomorphic decoration in the London-type industry runs parallel with anthropomorphic styles in which vessels are given human features.[4] These represent the height of decorative elaboration achieved by the London potters, giving rise to remarkable flights of fancy in the mid- to late thirteenth century. Whatever their original inspiration, the nature of the beasts on the Ludgate jug is somewhat ambiguous, although the cat-like features and the stance suggest a rampant lion. Naturalistic representation was never intended, and the artists and craftsmen who created the medieval menagerie were dependent largely on their imaginations to create a world of fantastical beasts whose significance was chiefly symbolic. Potters took their inspiration from what they saw around them, encountering depictions of alien creatures in church carvings and wall paintings, heraldic display, and a limited range of everyday items.

In the medieval bestiary, the lion was seen as the king of the beasts.[5] While many of their qualities are noble, lions with long bodies and straight hair were seen as fierce, in contrast with short-bodied and peaceable lions with curly manes.[6] The lion rampant was a powerful symbol, but closely allied to the lion was the leopard, the result of an illicit union between a lion and a “pard.” In medieval heraldry, the leopard was a savage beast with a spotted coat, represented as a lion with its head turned full-face (guardant).[7] The potter who made the Ludgate jug may have been aware of these allegorical meanings, but he was limited by his own undoubted ignorance of the subtleties of the bestiary and of the real animals that inspired them. The vessel would have formed part of the mundane world of the medieval Londoner, not someone at the highest level of society. Even so, such a large decorated jug was unlikely to have been in everyday use, reserved perhaps for special occasions. For whatever reason it was thrown away, it remains one of the most complete vessels of its kind to have been found in London.

A German Potter in Hampshire

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the pottery industry of the Surrey-Hampshire border was one of the most important suppliers of London’s everyday ceramics.[8] This industry was part of a centuries-old tradition of white-firing earthenwares made in the counties to the south of London.[9] At the end of the fifteenth century, the potteries in the Farnborough area of Hampshire phased out the manufacture of coarsely tempered utilitarian whitewares in favor of fine, white-bodied cups and drinking jugs.[10] Throughout much of the sixteenth century these supplied a specialized niche market for high-quality ceramics that were purchased in bulk by institutions such as the Inns of Court.[11] Around the middle of the century, dramatic changes began to take place in the Surrey-Hampshire border ware industry. These can be seen not only in technological developments but also in a considerable expansion in the range of vessels made (some of which are shown in fig. 3).

How and why did these changes come about? The rather unlikely-looking pot illustrated in figure 4 played a key role in unraveling the mystery of this transformation. Known by its German name Schweinetopf (lit. “pig pot”), this ungainly vessel would have been used in the manner of a casserole for slow-cooking meals, its four long legs raising it above the heat source and allowing the contents to simmer gently. The large, barrel-shaped body is enclosed at each end and a lid has been cut into the top, the edges chamfered so that it remains in place during use. Loop handles have been added to the lid and to each end of the body, to aid lifting. The only decoration is a band of thumbed clay applied around the opening for the lid, and there is a token spread of glaze over the top of the vessel.

So why is this particular pot significant? The illustrated vessel was found in London, although its distinctive form does not otherwise appear in the repertoire of the potteries that supplied the capital in the sixteenth century. It is, however, well known in the earthenware industries of the German Rhineland at the same date.[12] And this provides one of the clues to the ceramic revolution that took place in the Surrey-Hampshire border potteries in the second half of the sixteenth century.

Excavations at Farnborough Hill some forty-five years ago uncovered a complex of four kilns and a considerable quantity of ceramic waste, spanning the late fifteenth to late sixteenth centuries.[13] Reexamination of this important site in the early 2000s brought to light sherds from vessels made in the form of the Schweinetopf, as well as numerous other types—flanged dishes, tripod pipkins, skillets, chamber pots, and ceramic stove tiles—that apparently owed their origin to Rhenish forms.[14]

The wide range of “new” forms introduced into the industry led to the inevitable question of how Rhenish influence might have entered the potteries of the Surrey-Hampshire border. And the answer came from local historian Peter Tipton, whose researches had uncovered documents relating to an “allian” potter named Harmon Raignold, who had settled in Farnborough by 1586.[15] The name points to a German origin, although by the time of his death in 1609 Raignold was known as Herman Reynolds. Here lies the key to the ceramic “revolution” that took place in Farnborough in the late sixteenth century, one that was to have far-reaching effects on the role of the border ware industry as one of London’s main suppliers of domestic pottery for the next hundred years and more. The form was short-lived and never really caught on in England, with finds remaining very rare. Yet sherds from a border ware Schweinetopf have even been discovered on the site of the early English colony in Jamestown, Virginia,[16] a far cry from their origins in rural Hampshire and ultimately in the German Rhineland.

A German Pot in London

A German potter managed to transform one of the major ceramic industries of southeastern England in the later sixteenth century, yet pottery from the German Rhineland had been entering the country in considerable and increasing quantities since the fourteenth century. It continued to form the major component in London’s imported pottery market, flourishing under the trading network organized by the Hanse right through to the later seventeenth century.

Some of the most memorable pots I have encountered have been made outside England and brought into London as imported items in their own right (that is, as pots), as containers, or as souvenirs and gifts. One of these is illustrated in figure 5. Made in Cologne stoneware circa 1500–1550, this Bartmann jug has an exceptionally benign and beautifully modeled bearded face of the kind that gives these vessels their German name. The face mask is more or less rectangular in shape, molded in relief and applied to the neck of the jug in a technique pioneered by the stoneware potters of the Rhineland. Its features are carefully delineated, with flowing beard and well-formed nose and eyes, very different from the stylized, crude, and often fierce-looking face masks that adorn the later Bartmänner made in Frechen stoneware. A broad band of scrolled foliage, fruit, and blossom has been applied around the waist of the jug, with triangular panels containing acanthus leaves interspersed with applied lion-mask roundels above and below the central band.[17] The dark gray stoneware body with patchy brown surfaces is covered with a lustrous, speckled salt glaze.

The characteristic bearded face that appears on stoneware Bartmann jugs may represent the popular northern European folk tradition of the “Wild Man,” although later associations with the unpopular Counter-Reformation figure Cardinal Roberto Bellarmino have proved hard to escape.[18] Among all the Bartmänner held by the Museum of London, this one vessel stands out for me, perhaps in part because of its uncanny resemblance to my late friend and colleague Geoff Egan. But it is by no means the only example of a strikingly molded face mask I have known from London. Another example features in the fragment illustrated in figure 6, which comes from a site excavated in Magdalen Street, Southwark, in 1996.[19] It is similar, though not identical, to the complete vessel, and doubtless was made by a different potter and possibly at a different pothouse.

A natural channel close to the Thames foreshore had been filled with waste during the sixteenth century, then cleared, and again filled, circa 1630–1680, with rubbish that included a notably high proportion of imported pottery from France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Portugal.[20] Only a sample of the seventeenth-century finds was analyzed, although the face mask illustrated here came from the earlier feature. Yet the clarity and beauty of the naturalistic molding make this one fragment stand out, presenting a striking comparison with examples illustrated from the collection of the Kunstgewerbemuseum der Stadt Köln, including examples associated with depictions of Jesus.[21] Whether the Magdalen Street find and, indeed, the more complete Bartmann illustrated here were intended to depict Christ or the “Wild Man” of more earthy folk traditions is unknown. Perhaps the latter option is more likely, but what cannot be denied is that these two closely related items found in London represent the height of the stoneware potter’s art in the sixteenth century.

A Unique Delftware Dish from London

The splendid dish or charger illustrated in figure 7 is really without parallel in the corpus of English delftware. It is such a remarkable piece that its entry into this choice of ten pots from London simply could not be denied. The dish is painted in blue, ochre, yellow, green, and manganese (purple), and depicts a view of a city with castellated towers, possibly representing the Tower of London or an idealized London cityscape. The date “1600” is painted between the turrets, and an inscription around the central roundel reads: “THE ROSE IS RED THE LEAVES ARE GREEN GOD SAVE ELIZABETH OUR QUEENE.” The rim is decorated with Italianate arabesques on an ochre ground and has a blue dash edge. Donated to the Museum of London by the Marquess of Lincolnshire in 1915, this is the earliest known dated piece of English delftware.

The strong Italian inspiration in the decoration, especially around the border, seems to suggest that the dish was made in Italy, or possibly in Antwerp under the influence of immigrant Italian maiolica potters. However, chemical analysis of the fabric has shown that the piece can be attributed to London, and more specifically to the Aldgate pothouse, which was the only local source of delftware production at the beginning of the seventeenth century.[22] This view was also held by Frank Britton, without the benefit of scientific analysis.[23] He regarded the style of decoration as a likely consequence of the Italian ancestry of the Flemish potters who established the Aldgate pottery in 1571.[24]

Situated within the precinct of the former Holy Trinity Priory, the Aldgate pothouse was the first successful producer of delftware in England, founded by Jacob Jansen (Johnson) following an abortive attempt to set up a pottery in Norwich (Norfolk). Excavations within the priory precinct by the Museum of London in 1980 uncovered biscuit and glazed wasters that must have come from the Aldgate pothouse (fig. 8), adding to finds made by Peter Marsden and recorded by Ivor Noël Hume, in the City ditch, next to Bastion 6 of London Wall.[25] The significance of the inscription may be twofold, in the first instance expressing laudable patriotic sentiments. It also might refer to the house called the Sign of the Rose, where Jacob Johnson established himself in 1571, and where his second wife, Oyken Popping, continued the trade in merchandise produced at the pothouse after Johnson’s death in 1593.[26] None of these excavated finds, however, has yielded any examples, even in fragmentary form, whose decorative detail can be compared closely with the “Rose Is Red” dish. To date, this piece remains unique, a one-off special item even within the context of the often elaborately decorated and colorful products of London’s growing delftware industry.

A Rare Dated Delftware Bottle

The growth of London’s delftware industry in the early seventeenth century saw the establishment of several pothouses along the south bank of the Thames, in Southwark and Rotherhithe. One of the earliest of these was located at Pickleherring Wharf, where Christian Wilhelm and other immigrant potters from the Low Countries started producing delftware circa 1618.[27] The early products of the Pickleherring pothouse include a highly distinctive range of vessels decorated in blue on white with patterns derived from late Ming porcelain of China’s Wan Li period (1573–1619). Numerous sherds from various different forms painted with the design known as Bird on Rock have been recovered from many sites in London, and good examples of complete vessels are held in museum collections, including that of the Museum of London.[28] But the bottle illustrated in figure 9 has particular significance in that it was recovered archaeologically from a site excavated from the fill of a well in Parliament Square in 1995, and it has its own unique story to tell.[29]

The bottle is one of only six dated, complete examples of its kind known in museum and private collections.[30] Made in a shape that recalls the Rhenish stoneware Bartmann jug, it is decorated around the body with Chinese-inspired birds sitting on rocks, with flowers and foliage, painted in cobalt blue and blue wash over the opaque white tin-glazed body. Above and below this are panels of lattice or diaper decoration, and the base and outside edge of the handle are painted in solid blue. Beneath the handle terminal is the date 1627 (possibly 1628—the last number is unclear). All similar bottles are dated 1628, and there are examples of other forms, such as mugs, with later dates.[31] It is more usual, however, to find undated forms with Bird on Rock decoration, although the design was of fairly limited currency, mostly during the second quarter of the seventeenth century. One of the earliest examples, also held in the Museum of London’s collections, is an unusually flat plate, thought to have been made circa 1625–1630 (fig. 10).[32]

Christian Wilhelm was originally involved in the production of vinegar and smalt (finely ground blue glass with cobalt oxide) and moved into pottery manufacture circa 1618. In 1628 he was awarded an exclusive patent for the manufacture of galleyware.[33] Could the Westminster bottle be one of a small select group of dated decorative wares produced in support of his petition by demonstrating the quality of his work? Its discovery within the Palace of Westminster could well be significant in this respect, and since it was found in a deposit dating to the mid-eighteenth century, it doubtless had been carefully curated for some time before being discarded. It is the manner in which it was found, however, that makes this particular pot memorable. I can clearly recall the day when it was brought into the offices where I was working, carefully wrapped up and shown to the ceramic specialists to see if it was “of any interest.” Indeed it was! And not only was it recognized as an exceptionally important find, but the bottle had also suffered a very lucky escape from the fate that befalls so many archaeological ceramics when it was caught in midair by a quick-witted excavator as it fell out of the section of the well in which it had lain for three centuries.

An Early Dated Slipware Dish

This large dish is the third dated piece illustrated in this selection of London ceramic finds (fig. 11). Found in 2013, it is also the most recently discovered item included here. It is made in Metropolitan slipware and was recovered from the fill of a ditch on a site excavated in Tanner Street, Southwark, along with sherds from pottery dating to the mid-seventeenth century.[34] These include Surrey-Hampshire border wares, Essex-type fine redwares, and London-made delftware, as well as part of a dish in Chinese late Ming porcelain. Other finds from the fill suggest that the ditch was used as a convenient dumping ground for waste from nearby housing and possibly a tavern. The site has not yet been analyzed in detail, so the slipware dish is making an early appearance in this article, ahead of full publication.

Metropolitan slipware, so called because London was its main market, was made at pottery kilns located in and around Harlow in the county of Essex, some twenty-two miles to the northeast of the capital. Pottery manufacture had been taking place in this region from at least the thirteenth century, but Harlow wares played an especially important role in London’s ceramic supply in the seventeenth century, as the Tanner Street dish boldly proclaims in its date of 1632, in the very center of the decoration.

The dish is made in a fine red earthenware fabric typical of the post-medieval Harlow potteries and has a clear lead glaze on the inside only.[35] It has a broad flanged rim and shallow flared profile, and is decorated inside with fine white-trailed slip in a design arranged around the central cartouche containing the date. This design is based on a division of the decorated surface into four chevrons, each containing several nested V-shaped motifs, and separated by stylized double-ended tridents.[36] The rim has a series of alternating stars and groups of three parallel vertical lines. All these decorative motifs are common within the Metropolitan slipware potteries, used in endless combinations with other motifs that do not appear here.

Just as the Surrey-Hampshire border ware industry was revitalized by German potter Harmon Raignold in the late sixteenth century, and the manufacture of delftware was introduced into London by Low Countries potter Jacob Jansen, so too was the development of the Harlow slipware industry influenced by immigrant Dutch potter Emmanuel Emmyngs, who arrived in this area of Essex in 1592.[37] Metropolitan slipware did not become common in London before circa 1630, and as London was its chief market, production probably began only a short time before this. The earliest known example, now in the Museum of London, is dated 1630, so the Tanner Street dish, made only two years later, comes right at the beginning of the life of this highly decorative pottery industry.[38] It is a spectacular and significant discovery, all the more so for having been recovered archaeologically from a particularly important and rich assemblage of finds whose secrets have yet to be unlocked through analysis.

A Chinese-Inspired Italian Plate

Just as the delftware bottle illustrated in figure 9 shows the influence of Chinese late Ming porcelain in its overall design, so does the rather more fragmentary plate illustrated in figure 12. These two pieces are similar in date, but they come from very different sources: the bottle was made in London, and the plate near Genoa, Italy.

Finds of Italian maiolica from various centers are not uncommon in London excavations, but this particular one is something of a rarity when compared with the more usual Montelupo and Ligurian wares. It is decorated in a style known as calligrafico naturalistico, which is based on designs seen on imported porcelain made in China during the Wan Li period. These had a profound effect on potters working in centers as far apart as southern Iran and London. The first major shipments of late Ming porcelain, which had been captured from the Portuguese, were sold in the Netherlands in 1602 and 1604, and in 1606 a cargo from Amsterdam reached Genoa. Blue-and-white maiolica was being produced nearby in Albisola and Savona and, later, in Turin (by 1620), although the late Ming style of decoration probably did not become common until the 1630s.[39]

The plate is decorated in blue, ochre, and green, with the design elements delineated in manganese. The rim is divided into panels in a manner typical of Chinese kraak ware, each carrying stylized floral motifs and auspicious symbols; leaf motifs are painted in blue on the back of the plate. The central decoration is based on a delightful depiction of a hare leaping over a fence. The animal’s fur is indicated with close, carefully made brushstrokes, and in its use of color and the free rendition of the traditional design elements, the piece both declares its original Chinese inspiration and forms part of a distinctly European take on the Orient. A fish painted underneath the base is the mark of the Pescio or Pescetto family of Albisola and dates the plate to the second half of the seventeenth–early eighteenth century.[40]

The interweaving of stylistic influences by potters is endlessly fascinating, and this is in large part why this particular plate has been included in my selection. It was found in 1994 during excavations in a garden area within the outer precinct of the former St. John’s Priory, in Clerkenwell, North London, and remains one of the few examples of this kind of maiolica to have been found in London to date.[41] It was not a standard imported ware and might have been brought back to Clerkenwell as a souvenir of foreign travel, an eye-catching and exotic memento from the Mediterranean. Since it was some one hundred years earlier than the other artifacts in the feature in which it was found, it had clearly been valued and passed down through several generations until (presumably) someone accidentally broke it beyond repair. In its careful and lengthy curation, the plate can be compared with one of the other “special” pots included in this selection—the Bird on Rock bottle from Westminster.

A Southwark Windmill Charger

One of the more unusual examples of a delftware charger to have been recovered archaeologically in London is my next choice (fig. 13). Fragments of seventeenth-century chargers with blue-and-white or polychrome decoration are common finds in London excavations, but near-complete or reconstructable pieces are far less frequent. “Special” items usually would have been treated with greater care than everyday pots, and many of these have found their way into private and museum collections. Unhappily for its original owners, the item illustrated here, with its unique and distinctive decoration, did not survive the end of the seventeenth century.

The charger was found during excavations in 1975–1976 at Chaucer House, in Tabard Street, Southwark. It was part of a large ceramic assemblage recovered from the fill of a cesspit, which could be closely dated to circa 1660. A large proportion of the pottery consisted of everyday domestic forms in London-area redware and Surrey-Hampshire border ware, although about one-quarter of the vessels recovered were made in London delftware.[42] Among these were the fragmented remains of the large polychrome charger illustrated here. It is decorated in blue, green, yellow, and ochre with a highly unusual scene depicting a miller, standing with a sack over his shoulder in front of his mill. There are three more sacks of grain in the foreground, while on the right a horse carries additional sacks on its back. The post mill is typical of the seventeenth century, with a ladder leading up to the door and sails to the rear. A blue-dash border surrounds an inner band of herringbone design, also painted in blue. The vessel has a plain lead glaze outside, with the letter “H” painted in blue inside the foot rim.

The painting is fairly crude and with an untrained grasp on perspective, but the style is typical of mid-seventeenth-century Southwark delftware. The treatment of the grass in the foreground and its bright emerald green can be seen on chargers from pothouses in Southwark made between the 1630s and 1660s.[43] However, windmills are seldom depicted on English delftware, especially in the seventeenth century. A few examples of eighteenth-century date are known in museum and private collections, but these show only the mill and no people.[44] There is also an example in the Colonial Williamsburg collection, dated 1704 and probably English in origin.[45] The early date of the Chaucer House charger and its unusual slant on the decoration in showing the miller and his horse as well as the mill make this a significant find. Was it perhaps an individual commission, a one-off piece ordered by a prosperous Southwark miller to celebrate the mill that provided his livelihood? Whatever its genesis, it provides a wonderful insight into London’s past through the medium of its delftware industry.

A Glimpse of London’s Jewish Community

Most of the items in my choice of ten could lay claim to being unique. This term must, however, be qualified—they are unique as far as the body of ceramics used by Londoners that has survived the centuries is concerned. How unusual they were when first made is another matter, although many of the pots included here may well have been one-offs or rarities in their day, just as they are now. My next choice can certainly lay claim to be a highly unusual find within London’s rich archaeological record.

The item in question is an almost-complete delftware plate, decorated very simply with an inscription in Hebrew (fig. 14). It was discovered in a closely dated assemblage of pottery and other finds in the fill of a brick-lined cesspit, dating to the 1740s and excavated at 12–14 Mitre Street, near Aldgate.[46] A high proportion of the pottery consisted of kitchen and sanitary wares in London-area redware and Surrey-Hampshire border ware, as well as white salt-glazed stoneware, Chinese blue-and-white porcelain, and London delftware. Among these otherwise unexceptional finds, the Hebrew plate stands out as very different. I clearly remember emptying out the bag of sherds and puzzling over the curious decoration, which remained completely obscure until correctly oriented, when it became clear that it was in fact a word written in Hebrew. The shape and profile of the plate are typical of the early eighteenth century.[47] The decoration, executed in pale blue and dark blue, includes a simple Chinese-inspired border.[48]

The central inscription reads chalav (milk) and is carefully painted in ornamental Hebrew script of Ashkenasi style.[49] It can be related to Jewish dietary laws and the separation of dairy and meat products in observant Orthodox households. These require the use of separate sets of crockery for each food group, with those intended for meat inscribed with the word basar. No other excavated examples of such plates have yet been identified in England, although there is a delftware plate marked basar in the Jewish Museum, in Camden Town, London.[50] That example has added floral decoration and can be dated to the 1760s, but it was donated to the museum rather than excavated archaeologically. Tin-glazed Passover plates are also known from excavations in Amsterdam, including one from Waterlooplein inscribed Pesach and basar.[51]

The Mitre Street area was an early focus of Jewish settlement following the Readmission under the Commonwealth. Sephardic Jews from Spain, Portugal, and the Netherlands and Ashkenasi Jews from Germany all settled in this part of London. The delftware plate was undoubtedly a special commission, most likely ordered directly from a delftware pothouse, or perhaps from a retailer specializing in Judaica. It provides a fascinating and all too rare insight into the everyday life of one of the many diverse peoples that made up the eighteenth-century metropolis, and as such could not escape inclusion here.

Fine Porcelain from an Eighteenth-Century Coaching Inn

My last choice is a personal favorite out of all the ceramics I have worked on over the past thirty-seven years, largely because of the naive charm of its decoration and also because it is part of a highly significant assemblage of pottery, glass, and other finds that formed a particularly stimulating research project. The item in question is a cylindrical mug made in Lowestoft porcelain (fig. 15) and is an early and rare find. It is decorated in underglaze blue with a Chinese-inspired design that features a statuesque lady of European appearance, holding a parasol and standing in a rocky landscape with a very large bird flying overhead. The few known parallels are dated to the early 1760s.[52] The lattice and flower border decoration inside the rim can be dated to 1757–1766.[53] The mug has a slightly flared base, which can be compared with an example in Norwich Museum dated to circa 1760–1764.[54] Inside the foot rim is a painter’s tally mark, probably “7,” which ties in with a system of painters’ numbers used at Lowestoft between 1757 and 1775.[55]

The Lowestoft mug was found in a large group of late-eighteenth-century pottery excavated from the fill of a well in the courtyard of a former coaching inn, The King’s Arms, in Uxbridge, Middlesex (now West London).[56] Apparently part of a wholesale clearance of damaged or outmoded and unwanted crockery, the finds were most likely thrown away circa 1785–1800, perhaps when a new licensee took over the running of the inn. They include parts of several dinner services in creamware, sherds from thirty-six vessels in Chinese porcelain decorated in blue-and-white and famille rose palette, and from eighteen vessels in English soft-paste porcelain from Lowestoft, Worcester, and Caughley.[57]

The high proportion of porcelain forms from various sources made for drinking hot beverages highlights one of the principal functions of a busy coaching inn during the eighteenth century, as a focus of hospitality for travelers and entertainment among the local community. These account for 16.5 percent of the whole assemblage and may hint at provision for a more select clientele.[58] The finds also give a valuable glimpse into the wealth of ceramics available within the wider London area during the later eighteenth century. Lowestoft, a well-known seaside resort situated on the Norfolk coast, near Great Yarmouth, is a long way from Uxbridge. The products of its porcelain industry were very popular locally as “trifles”—gifts and souvenirs—and perhaps it is in this context that the King’s Arms mug reached Uxbridge. It may well be that the licensee or one of their family found the vessel as irresistible as I do, and so brought it back from a holiday by the sea as a memento. Or it could be that the mug was purchased from a London china seller along with other wares used to furnish the inn. Either way, it provides a rare insight into the tastes of the time and, as such, makes a fitting finale to my choice of ten key ceramics from London.

JACQUI PEARCE graduated from University College London in 1977 with a 1st Class Honours degree in Anglo-Saxon archaeology, then joined the Museum of London’s Department of Urban Archaeology as a specialist in medieval and later ceramics. She is now Senior Specialist in Ceramics with MOLA (Museum of London Archaeology) and has written and coauthored numerous major papers and books, including four parts of the standard Type-Series of Medieval Pottery from London, and one volume in a series on the pottery of London circa 1500–1700, as well as a study of the kiln site at Farnborough Hill in Hampshire. She has been involved in the establishment and maintenance of the MOLA Fabric Reference Collection, the principal fabric type-series for the London area. Jacqui also specializes in clay tobacco pipes from the London region and beyond, and has been instrumental in the establishment of the Museum of London’s Clay Tobacco Pipe Makers’ Marks website. Other areas of specialization are medieval and later glass and a wide range of other artifacts.

Jacqui is a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London and a Member of the Institute for Archaeologists. She served as assistant editor then coeditor of Medieval Ceramics for more than ten years and is currently joint editor of Post-Medieval Archaeology. She is also a long-standing committee member of the English Ceramic Circle and a Trustee of the National Clay Tobacco Pipe Archive. She has been teaching regular classes in archaeological finds work since 2001, initially through Birkbeck College, University of London, and subsequently with local archaeology groups in the London area.

Excavations were carried out on the site, located between Carter Lane, Pilgrim Street, and Ludgate Hill, by the former Department of Urban Archaeology of the Museum of London (DUA); site code PIC87 context [3058].

Jacqueline E. Pearce, Alan G. Vince, and M. Anne Jenner, A Dated Type-Series of London Medieval Pottery, Part 2: London-Type Ware, London and Middlesex Archaeological Society Special Paper 6 (London: London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, 1985).

Ibid., pp. 30–31.

Ibid., p. 30, fig. 56.

Janetta Rebold Benton, The Medieval Menagerie: Animals in the Art of the Middle Ages (New York: Abbeville Press, 1992), p. 85.

Ibid., p. 86.

Anne Payne, Medieval Beasts (London: British Library, 1990), p. 22.

Jacqueline Pearce, Post-Medieval Pottery in London, 1500–1700, Volume 1: Border Wares (London: HMSO, 1992).

Jacqueline Pearce and Alan Vince, A Dated Type-Series of London Medieval Pottery, Part 4: Surrey Whitewares, London & Middlesex Archaeological Society Special Paper 10 (London: London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, 1988).

Jacqui Pearce and Peter Tipton, “How Technology Transfer from the Continent Transformed English Ceramic Manufacture in the Sixteenth Century,” Transactions of the English Ceramic Circle 22 (2011): 182.

Jacqueline Pearce, Pots and Potters in Tudor Hampshire: Excavations at Farnborough Hill Convent, 1968–72 ([Guildford]: MoLAS/Guildford Borough Council, 2007), p. 11.

Ibid., p. 93; David R. M. Gaimster, The Historical Archaeology of Pottery Supply and Demand in the Lower Rhineland, AD 1400–1800, Studies in Contemporary and Historical Archaeology 1, BAR International Series 1518 (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2006), fig. 53, no. 1.

Excavations were carried out between 1968 and 1972 by Felix Holling, of Guildford Museum, and John Ashdown.

Pearce, Pots and Potters in Tudor Hampshire, pp. 93–94, fig. 53, nos. 267–69; pp. 194–99.

Ibid., p. 13; Pearce and Tipton, “Technology Transfer,” p. 187.

Beverly A. Straube, “This Little Piggy Went to Virginia,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2005), pp. 217–19.

David R. M. Gaimster, German Stoneware, 1200–1900: Archaeology and Cultural History (London: British Museum Press, 1997), fig. 37l.

Ibid., p. 192.

Steve Chew and Jacqui Pearce, “A Pottery Assemblage from a Seventeenth-Century Channel at 12–26 Magdalen Street, Southwark,” London Archaeologist 9, no. 1 (1999): 22–28.

Ibid., fig. 4.

Gisela Reineking von Bock, Kunstgewerbemuseum der Stadt Köln: Steinzeug, 3rd ed. (Cologne: Kunstgewerbemuseum der Stadt Köln, 1986), nos. 253, 256.

Michael Hughes and David Gaimster, “Neutron Activation Analyses of Maiolica from London, Norwich, the Low Countries and Italy,” in Maiolica in the North: The Archaeology of Tin-Glazed Earthenware in North-West Europe c. 1500–1600, British Museum Occasional Paper 122, edited by David Gaimster (London: British Museum, 1999), pp. 64–65.

Frank Britton, London Delftware (London: Jonathan Horne, 1987), p. 105, fig. 24.

Ibid., p. 27.

Ibid., p. 28; Ivor Noël Hume, Early English Delftware from London and Virginia (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1977), p. 111, fig. XIX.

Noël Hume, Early English Delftware, pp. 111–14.Noël Hume, Early English Delftware, pp. 111–14.

Britton, London Delftware, p. 35.

For example, see ibid., figs. 30–32; Noël Hume, Early English Delftware, pp. 38–43, pls. 30–31, 37–38, 40–41; Kieron Tyler, Ian M. Betts, and Roy Stephenson, London’s Delftware Industry: The Tin-Glazed Pottery Industries of Southwark and Lambeth, MoLAS Monograph 40 (London: Museum of London Archaeology Service, 2008), figs. 42–44.

Christopher Thomas, Robert Cowie, and Jane Sidell, The Royal Palace, Abbey and Town of Westminster on Thorney Island, MoLAS Monograph 22 (London: Museum of London Archaeology Service, 2006), pp. 129–30.

Ibid., p. 129.

See, e.g., Britton, London Delftware, fig. 31, dated 1630.

Ibid., fig. 32.

Tyler et al., London’s Delftware Industry, p. 28.

Jacqui Pearce, “Century House, Tanner Street: Assessment of the Post-Medieval Pottery,” unpublished Museum of London Archaeology report, 2013.

Wally Davey and Helen Walker, The Harlow Pottery Industries, Medieval Pottery Research Group Occasional Paper 3 (London: Medieval Pottery Research Group, 2009), pp. 25–26.

Ibid., pp. 75–76, fig. 36.

Ibid., p. 97.

The jug (Museum of London, A27662) carries the inscription “OBAY THE KING 163,” in which the “0” of 1630 appears to run into the “O” of OBAY.

Julia Poole, Italian Maiolica, Fitzwilliam Museum Handbooks (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), p. 110.

Arrigo Cameirana, Ceramica in Banca, 50 Maioliche Liguri della Casa di Risparmio di Genova e Imperia (Albisola Superiore: Museo della Ceramica “Manlio Truccio,” 1989), p. 64.

Barney Sloane and Gordon Malcolm, Excavations at the Priory of the Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem, Clerkenwell, London, MoLAS Monograph 20 (London: Museum of London Archaeology Service, 2004), pp. 346–47 (the plate was originally misidentified as Portuguese in origin).

Roy Stephenson, Medieval and Later Pottery from Chaucer House, unpublished Museum of London archive report, undated.

Michael Archer, Delftware: The Tin-Glazed Earthenware of the British Isles (London: HMSO in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1997), pls. 33, 34, 38, probably made at Pickleherring, Rotherhithe, or Montague Close.

Frank Britton, English Delftware in the Bristol Collection (London: Sotheby Publications, 1982), figs. 14.41, 14.42.

John Austin, British Delft at Williamsburg (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in association with Jonathan Horne Publications, 1994), p. 132, fig. 164.

Jacqueline Pearce, “A Rare Hebrew Plate and Associated Assemblage from an Excavation in Mitre Street, City of London,” Post-Medieval Archaeology 32 (1998): 95–112.

Britton, London Delftware, p. 194, profile J.

Louis L. Lipski and Michael Archer, Dated English Delftware: Tin-glazed Earthenware, 1600–1800 (London and Scranton, Pa.: Sotheby Publications, 1984), no. 328, dated 1724.

Pearce, “A Rare Hebrew Plate,” p. 105.

Jewish Museum, 1982-10-19.

Jerzy Gawronski and Ranjith Jayasena, “A Mid-Eighteenth-Century Mikveh Unearthed in the Jewish Historical Museum in Amsterdam,” Post-Medieval Archaeology 41, no. 2 (2007): 213–21, fig. 1.

Geoffrey A. Godden, The Illustrated Guide to Lowestoft Porcelain (London: Herbert Jenkins, 1969), fig. 81; Antique Dealer and Collectors Guide (October 1998): 12.

Sheenah Smith, Lowestoft Porcelain in Norwich Castle Museum, vol. 1, Blue and White and Excavated Material ([Norwich]: Norfolk Museums Service, 1975), p. 261.

Ibid., p. 146, no. 216, fig. p. 155.

Ibid., pp. 37–38, 254.

Jacqueline Pearce, “A Late Eighteenth-Century Inn Clearance Assemblage from Uxbridge, Middlesex,” Post-Medieval Archaeology 34 (2000): 144–86.

Ibid., pp. 148–61.

Ibid., p. 171.