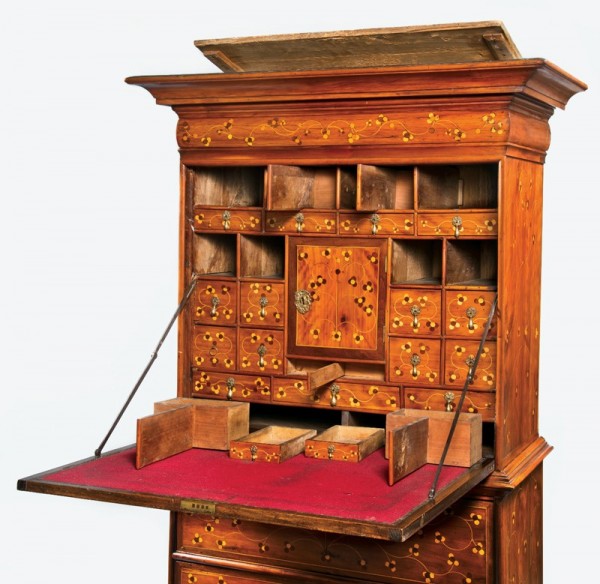

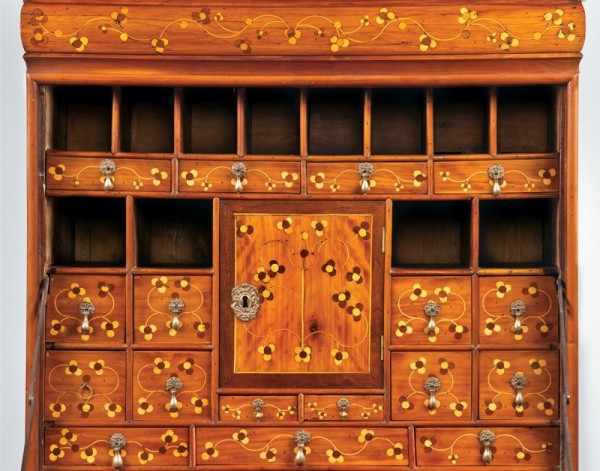

Scrutoir, Kings or Queens County, Long Island, New York, 1700–1725. Red cedar, red cedar and walnut veneers, and light and dark wood inlay with Atlantic white cedar, sweet gum, oak, chestnut, yellow poplar, and hard pine. H. 67", W. 41 3/4", D. (cornice) 22". (Courtesy, Museum of the City of New York; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Photograph of the Brinckerhoff scrutoir from The Family of Joris Dircksen Brinckerhoff, 1638 (New York: Richard Brinkerhoff Publisher, 1887).

Scrutoir stamped “Edward Evans/1707,” Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1707. Black walnut with white cedar and yellow pine. H. 66 1/2", W. 44 1/2", D. 19 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Scrutoir illustrated in fig. 3 with the fall front open.

Scrutoir, Rhode Island, 1700–1730. Walnut and walnut veneer with chestnut and white pine, H. 66", W. 39 3/4", D. 18 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

Scrutoir illustrated in fig. 5 with the fall front open.

Desk-on-frame, New York City or vicinity, New York, 1695–1720. Sweet gum and mahogany veneer with yellow poplar. H. 35 1/4", W. 34 1/2", D. 24 1/8". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Desk, New York or Rhode Island, 1700–1730. Black walnut, unidentified burl veneer, and Cuban oyster wood (interior drawer pulls) with white pine, black walnut, yellow poplar, and cherry. H. 41 1/4", W. 36 1/4", D. 19 5/8" (closed). (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Bayou Bend Collection.) This desk is catalogued as New York by Bayou Bend but after the discovery of the Child scrutoir (see figs. 5 and 6) is now considered by some scholars to be of Rhode Island origin.

Detail of the interior of the scrutoir illustrated in fig. 1, showing its original long iron hinges, secret drawers removed, and hinged top board for a secret compartment open. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Scrutoir, England, ca. 1695. Walnut, burl elm, and seaweed marquetry; secondary woods not recorded. H. 65", W. 46", D. 19 1/2". (Private collection; photo, courtesy Millington Adams Ltd., Knutsford, Cheshire, Eng.) This scrutoir is illustrated in Percy MacQuoid’s Age of Walnut (1905). The turned feet and drop handles are restored.

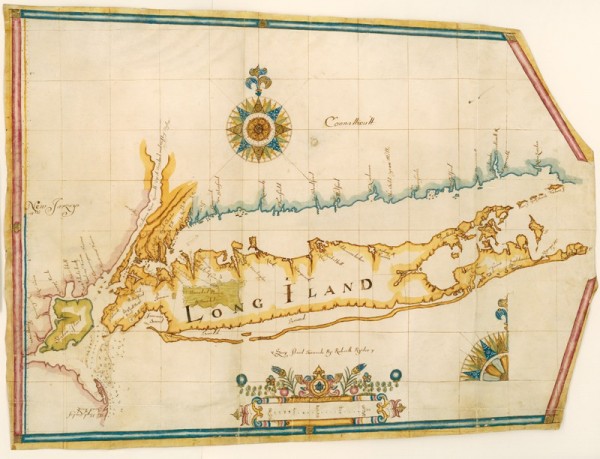

Robert Ryder, Long Iland Siruade by Robartte Ryder (London, [1679?]). 23 3/4" x 31 5/8". (Courtesy, John Carter Brown Library at Brown University.)

Detail of the map illustrated in fig. 11, showing the town of Newtown and Flushing Bay.

Detail of the secret drawer from the scrutoir illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the side of a drawer from the scrutoir illustrated in fig. 1. The front, sides, and rear boards are rabbeted on their lower inside edge, and the bottom is nailed into the rabbets on all four sides. Walnut banding on the drawer front covers the end grain of the dovetails, while the steep pitch of the top edge is a feature characteristic of the drawers in New York kasten. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

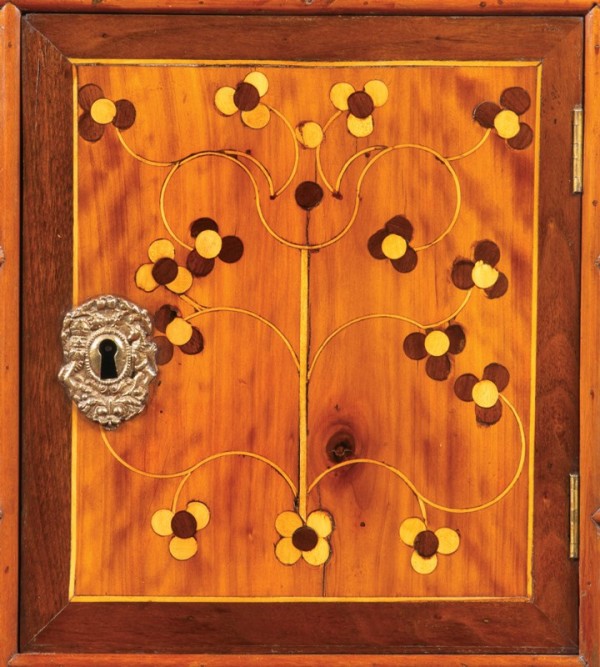

Detail of the central interior door of the scrutoir illustrated in fig. 1, showing the cast brass keyhole escutcheon. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of two interior drawers of the scrutoir illustrated in fig. 1, showing the original pulls with cast brass backplates. (Photo,Gavin Ashworth.)

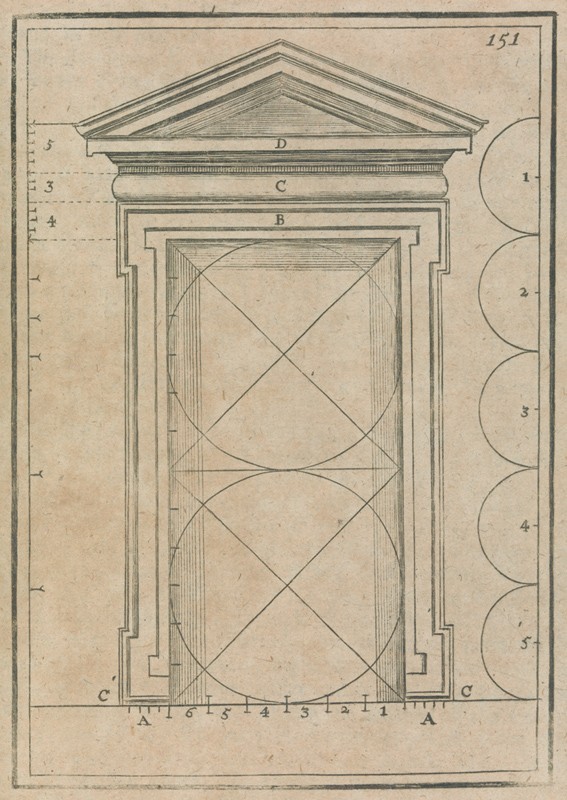

Plate from Andrea Palladio, The First Book of Architecture, translated from the Italian with an appendix on doors and windows by Pierre Le Muet (1591–1669). Translated into English by Godfrey Richards (London: Eben. Tracy, 1716).

Interior doorway in the Pieter Bronck House, Coxsackie, New York, 1700–1738. (Courtesy, Bronck Museum, Greene County Historical Society, Coxsackie; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Kast, Albany, New York, 1710–1735. Gum with tulip poplar and white pine. H. 78 1/2", W. 75 7/16", D. 29 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the cornice of the scrutoir illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

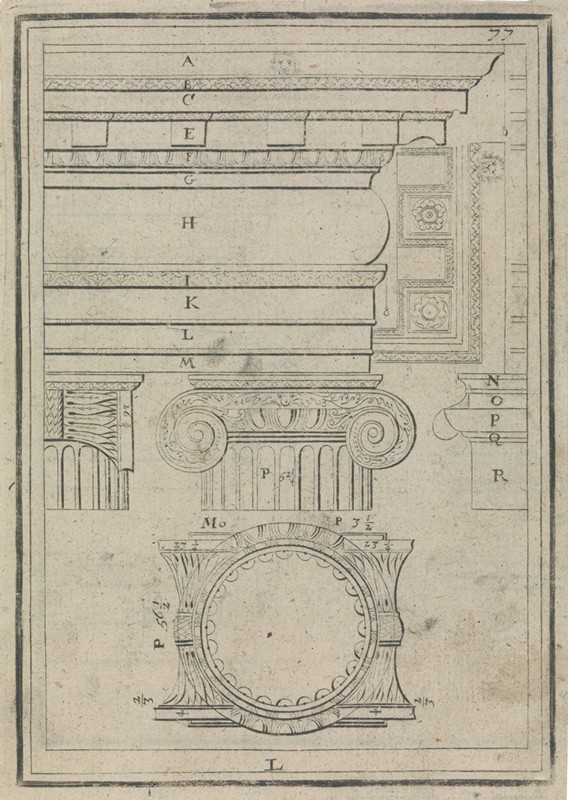

Tavola IX, Capitello, e cornicione Dorico, from Regola delle cinque ordini d’architettura di Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola (Rome, 1563). (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

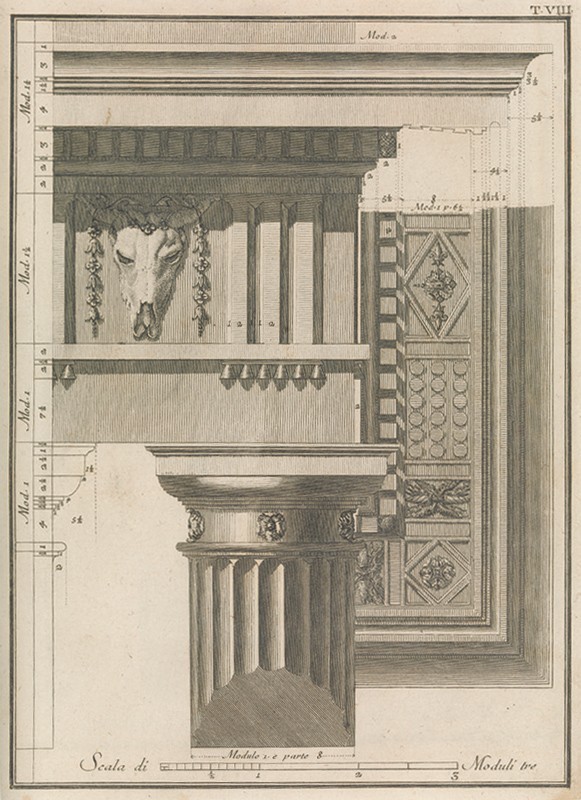

Plate showing an entablature in the Ionic order from The First Book of Architecture by Andrea Palladio Translated out of Italian...by Godfrey Richards (London: James Knapton, 1721). (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Back of the scrutoir illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Chest of drawers, southeastern Pennsylvania, 1710–1735. Walnut with white cedar, yellow pine, and oak. H. 41 1/2", W. 42 5/8", D. 23 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The chest is made in two parts.

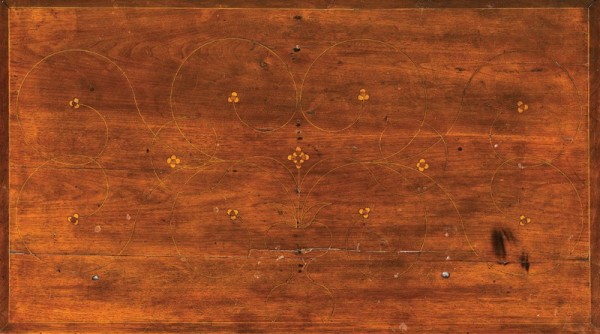

Detail of the top of the chest of drawers illustrated in fig. 24. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Scrutoir illustrated in fig. 1 with the fall front open. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the interior of the scrutoir illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

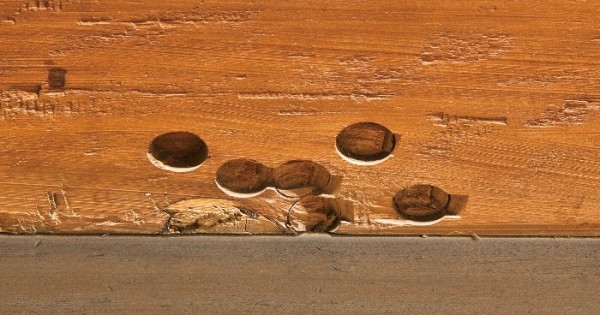

Detail of the back face of the lower drawer in the scrutoir illustrated in fig. 1, showing circular recesses cut with an incannel gouge. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the fall front of the scrutoir illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Left side of the scrutoir illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the figure inlaid into the left side of the upper case of the scrutoir illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jan (Pietersz.) Saenredam (ca. 1565–1607) after Abraham Bloemart (1566–1651). Adam and Eve. Engraving. 11" x 7 15/16". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Nicolaes Visscher I (1618–1679), Earthly Paradise or the Garden of Eden, map drawn for inclusion in Abraham van den Broeck’s Dutch Staten Bible, 1657. (Courtesy, Geographicus.)

Gerardus Duyckinck I (1695–1746), Christ Healing the Blind Man, ca. 1725–1730. Oil on canvas, 35 1/4" x 45". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Rarely can the word unique be used to describe a piece of early American furniture, but in the case of the profusely inlaid cedar scrutoir (fig. 1) that is the subject of this article a more apt description could hardly be found. The existence of this scrutoir was noted as early as 1852, when it was described in the Annals of Newtown in Queens County, New York as an “antique writing desk, to which tradition ascribes a Holland origin.” In 1887 the scrutoir was published again in The Family of Joris Dircksen Brinckerhoff, 1638, where a short chapter written by its then owner, T. Van Wyck Brinkerhoff (1822–1891), is dedicated to it (fig. 2). Among other things, this is what he had to say:

This secretary was brought to New Amsterdam by Joris Dircksen Brinckerhoff, the first representative of the family in America in 1638. It is five feet six inches high, three feet six inches wide, and twenty-two inches deep.... It contains six different secret drawers....In the upper part there is a large space for silverware, where the family silver was kept secreted. This, too, has a private approach of its own. The wood of the secretary is of a light mahogany color and is very handsomely inlaid with satin, wood and ebony....This ancient piece of furniture is the most precious heirloom of the family. It speaks of Joris Dircksen, our honored ancestor, and has a language of common interest to us all....It has been given by repeated wills to the sons of the name, and has always been an object of especial interest.[1]

Such an early and carefully recorded family history is a boon for the furniture historian and provides an essential baseline for interpreting the Brinckerhoff scrutoir in place and time. Yet challenging and provocative questions nearly as numerous as its secret drawers remain. If, as all physical and stylistic evidence suggests, Joris Dircksen Brinckerhoff (1604–1661) could not have been its original owner, then who actually commissioned this ambitious and complex piece of baroque case furniture? How can the hybrid nature of its design, which differs markedly from English William and Mary scrutoirs and its known American counterparts be explained? Are the patterns expressed in line-and-berry inlay on its sides and front meant to convey some meaning, and, if so, what were the motivating factors for the client who conceived its iconographic program?

While the distinctive and exuberant inlay playing across the broad, planar surfaces of the Brinckerhoff scrutoir makes it unique, the form itself is remarkably rare in American furniture, with only two other examples known: a signed and dated scrutoir made in 1707 by David Evans of Philadelphia (figs. 3, 4); and a recently discovered example listed in the will of James Child of Swansea, Massachusetts, as “one Chist [chest] of Drawers & Cabinett £5” (figs. 5, 6). Whether fall-front scrutoirs were as uncommon in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries as their rarity today suggests is difficult to tell based on period inventories from New York, Pennsylvania, and New England that include such terms as scriptore, scriptoire, scredoar, scritoire, and screwtor, all refashioned versions of the French escritoire, meaning a writing desk containing interior compartments for stationery and documents. Unfortunately, these words appear to have been used interchangeably to describe the fall-front scrutoir and the other writing-desk forms popular in the period, the desk box-on-frame (fig. 7) and the slant-top desk (fig. 8). The New World of Words (London, 1706) describes a “Scrutoir, or Scritory” as “a sort of large Cabinet with several Drawers, and a place for Pen, Ink, and Paper, the Door of which opening downwards, and resting upon Frames or Irons, serves as a Table to write on.” There is room in this definition for the “Door” to be either slanted or vertical, but it is the mention of “Irons” that assures us that a fall-front scrutoir is being described here. The Brinckerhoff, Evans, and Child scrutoirs all have long iron hinges that support their writing falls in the open position (fig. 9). The “Irons” on the Brinckerhoff scrutoir are unquestionably original, although it seems that chains also were used for this purpose, as indicated by a reference to “4 pr Scrutore Chains with two dozen bolts” in the inventory of a shopkeeper in New York in 1692.[2]

Another way to distinguish whether a particular inventory reference describes a scrutoir like the Brinckerhoff, Evans, or Child examples is by the value assigned to it, fall-front writing cabinets being the larger and more complicated form to make. The Child family scrutoir valued at £5 in 1738, for instance, was among the most valuable household items in the inventory. At New York (Manhattan) in 1704 “2 schrutoors”—a spelling furniture historian Luke Vincent Lockwood cleverly quipped, “none but a Dutchman could have executed”—were assigned a joint value of £13, indicating that they, too, were fall-front writing cabinets. A “black walnut scruptore” valued at £10 that stood in Gertruy Van Cortlandt’s parlor when her household inventory was recorded at New York in 1724 may also be of this type, although there is a chance that it could be a desk-and-bookcase. Also in 1724 the inventory of George Duncan of New York includes one “inlaid scriptore” valued at £6.5 as well as a “cedar ditto,” references that have particular resonance in relation to the Brinckerhoff scrutoir. Was Duncan’s “inlaid scriptore” locally made or imported? If the latter, then perhaps it had light wood arabesque marquetry inlay on a dark ground like the scrutoir illustrated in figure 10 or panels of flower marquetry, an earlier seventeenth-century technique that remained popular into the William and Mary period.[3]

Wealthy New Yorkers are known to have appointed their homes with fine imported Dutch, English, and even exotic East India furniture in the late seventeenth century. The several carved and veneered walnut Dutch kasten imported to New York in the last quarter of the seventeenth century with histories of ownership in the Beekman, Livingston, and Staats families attest to this fact. No such case furniture in the English Restoration or William and Mary styles and with an early history of ownership in New York is known, but period references strongly hint at its presence there. For instance, in 1692 Lawrence Deldyke of New York is recorded as owning an olive wood cabinet, while in 1705 Colonel William Smith owned a chest of drawers of walnut and olive wood valued at £15, which, as that number suggests, may have had oyster veneers or perhaps even a marquetry panel on the top. English baroque scrutoirs with light-wood marquetry like the example illustrated in figure 10 may generically have had an influence on the inlaid decoration of the Brinckerhoff scrutoir, but the language of this ornament actually comes from a source much closer to home in southeastern Pennsylvania. Some furniture historians have claimed that the decoration on the Brinckerhoff scrutoir “reflects the Dutch aesthetic for ornate surfaces,” or that it “is a reflection, though distant, of the elaborate marquetry of Dutch baroque cabinetwork, which was imitated in England.” But these explanations ignore the essential fact that this American original was produced in an area on western Long Island that was a meeting ground of Dutch and English Quaker cultures from the mid-1600s onward (fig. 11).[4]

Treasured Family Icon

When T. Van Wyck Brinkerhoff wrote of the history of the Brinckerhoff scrutoir, he believed it to have been a prized possession of eight consecutive generations of Brinckerhoffs in America. The Brinckerhoffs were among the earliest and most respectable families to settle in the towns established on western Long Island in the early Dutch period. The progenitor of the family, Joris Dircksen Brinckerhoff, was born in 1604 in the northeastern Dutch province of Drenthe and immigrated with his wife, Susannah Dubbels (1602–1676) and their three sons and daughter to New Netherland in 1638, eventually settling on a grant of land acquired at Breukelen (Brooklyn) in 1646. In the Annals of Newtown, Joris Dircksen is described as “a man of worth” who served as an elder in the Reformed Dutch Church of Brooklyn at the time of his death in 1661. Joris Dircksen did not live long enough to witness the English takeover of New Netherland in 1664; the declaration by James II in 1685 making New York a royal province; Leisler’s Rebellion, which broke out with special virulence on Long Island in the wake of England’s Glorious Revolution (1689–1691); or the ascension of William and Mary to the English throne. However, within his lifetime he established for his family in the New World a foundation of wealth and a reputation for probity, industriousness, and piety. A traditional family history that Joris Dircksen brought the Brinckerhoff scrutoir with him to New Netherland from Holland, however, is simply not possible given its style and the fact that it is made entirely of native American woods, including red cedar, Atlantic white cedar, yellow poplar, gum, and chestnut. Its earliest credible owner, therefore, according to its line of descent, would be Joris Dircksen’s third-eldest son, Abraham Jorise Brinckerhoff, a man who would have experienced directly and been sensitive to the changeover from Dutch to English rule and the emerging influence of the English William and Mary style on New York furniture in the late seventeenth century.[5]

Abraham Jorise was born in the Netherlands in 1631 and died at Newtown in Queens County, Long Island, in 1714. He spent his youth and early manhood on his father’s farm in Brooklyn, and in 1660 he married Aeltie Strycker (1632–1697), the daughter of Jan Strycker of Flatbush. Abraham and his wife first settled on property he had acquired in nearby Flatlands, where, as his father had done before him at Brooklyn, he served as an elder in the Reformed Dutch Church. Trusted, respected, and literate, he was chosen as a local magistrate in 1673. Abraham was apparently quite entrepreneurial as well, partnering with his brother-in-law Cornelis Jansen Berrien in 1684 to purchase more than four hundred acres of land at the head of Flushing Bay in the vicinity of Newtown (fig. 12), an area now called Elmhurst, Queens, that they would hardly recognize today yet glimpsed by countless airline passengers on their descent into La Guardia Airport as a teeming urban landscape below. In 1685 Abraham and his brother-in-law divided that land and, after also having purchased another large farm on Flushing Meadow, established a family homestead there. According to the Brinckerhoff family biography, “the lands at Newtown were fertile and productive, and by reason of thrift and good management, Abraham Jorise, beside raising his family of nine children, acquired quite a competency of goods, chattels, and estates, which he afterwards divided among his children.” Whether his descendant’s most treasured family possession was among these goods and chattels remains unknown, however, since Abraham Jorise’s will, despite the claims of its existence in 1887 by the family historian, T. Van Wyck Brinkerhoff, has yet to be found.[6]

A second candidate as the first owner of the Brinckerhoff scrutoir is Abraham’s eldest son, Joris Brinckerhoff (1664–1729), who succeeded to the paternal farm on Flushing Bay and also acquired several other farms in the area during his lifetime. At his death he distributed these farms among his five sons, one of whom, Teunis (1697–1784), according to family history, passed the scrutoir on to his son George (1726–1797). The record does not indicate whether Joris, like his father, was a church elder or a magistrate. Although his will survives, there is no mention in it of the scrutoir or any other piece of furniture. The only possession Joris singled out as a bequest was his silver beaker, which he left to his eldest son, Abraham (1694–1767), as “his birthright.” To his “Dearly beloved wife Annetie” he left his “Plantation” as well as “all my personal Estate,” which may have included the scrutoir. Curiously, written with a red lead pencil in period script on the side of one of its hidden drawers, as well as on the board that withdraws it from its hiding place in the interior, is the letter “J”—possibly his initial (fig. 13). Sadly, this tantalizing clue neither confirms nor denies Joris’s original ownership of the scrutoir, since he could have written his initial on it at various points in his life, even after he inherited it from his father’s estate in 1714. It should be remembered that Joris succeeded to the paternal farm, or “plantation,” which included the family house and possibly its contents as well.[7]

Finally, it is within the realm of possibility that Joris’s previously mentioned son, Teunis, was the original owner of his family’s treasured heirloom. Teunis was born in 1697, married in 1721, and, like his grandfather Abraham, was a church elder and a civil magistrate in his lifetime. His ownership of the scrutoir, therefore, would have to extend its possible date of manufacture into the 1720s, which may be a stretch given its fairly early type of drawer construction (fig. 14) and the style of its original hardware (figs. 15, 16). T. Van Wyck Brinkerhoff relates an interesting story about the scrutoir in the Brinckerhoff family biography that also casts doubt on Teunis’s being its original owner:

It passed by the will of Tunis Brinckerhoff who was born in 1697 and lived to be eighty-seven years old to his only son George and is called “The Drawers.” My grandfather, whose name was George and whose father’s name was George, gave “The Chest of Drawers to his son Tunis” and mentions as the reason “because he was named after his great great-grandfather Tunis.” I have myself heard my grandfather and Uncle Morg, his colored family servant, both say, that the old secretary came from Holland, “for old grandfather Tunis had told them so.” They were both of them young men when he died. Grandfather Tunis must be accepted as the very best of authority. He was seventeen years old when his grandfather Abraham Joris died, and lived in the old Flushing Bay homestead with him and therefore must have known all about it.

T. Van Wyck Brinkerhoff’s grandfather and his servant Uncle Morg may not have been correct in the story they passed on that the scrutoir came from Holland, but if “old grandfather Tunis” had commissioned it during his lifetime, it certainly seems unlikely that he would have started such an ill-founded rumor. In fact, this account, admittedly many years after the fact, places the scrutoir in the home of Abraham Jorise Brinckerhoff at the time of his death in 1714, suggesting that he was its first owner.[8]

Family histories often get some details wrong, but like all generalities and stereotypes they are more often than not based on some underlying truth. The notion that the ownership of their family’s “old secretary” reached back to the first Brinckerhoffs to arrive on these shores may be accurate after all, since it has a fifty-fifty chance or better of having been made for Abraham Jorise Brinckerhoff, also an immigrant when he arrived in New Netherland as a boy with his parents in 1638. Without Abraham’s will or household inventory to prove that he owned the scrutoir at the time of his death, however, we simply must live with the ambiguity that it could have belonged originally to either him or his son, Joris.

Creolization of a William and Mary Form

The broad overall proportions, flattened bun feet, drawer arrangement, and relatively small cornices on the Evans and Child scrutoirs are design features that align them precisely with their English William and Mary counterparts (compare figs. 3, 5, and 10). The Brinckerhoff scrutoir, by contrast, has a character all its own. Aside from its profusion of inlaid ornament, the most striking aspect of that object in relation to the Evans and Child examples and to English baroque scrutoirs is its attenuated proportions and boldly scaled cornice and feet (fig. 1). Standing only 1 1/4 and 1 3/4 inches taller than Evans and Child scrutoirs respectively, the proportions of the Brinckerhoff example make it a more classically architectonic form. They are reminiscent of Palladian-style portals (fig. 17) as well as interior and exterior doorways with cornices in early New York Dutch houses (fig. 18). The large, slightly flattened ball feet on the Brinckerhoff scrutoir, turned from blocks of red cedar, offer a solid and appropriately scaled foundation for the architectural mass of the form. They also take up a fair amount of the available space below the standard ± thirty-inch height of its writing surface, which may partially explain why the Brinckerhoff scrutoir has two deep drawers of equal size in the lower case rather than the three tiers of graduated drawers (top tier split) typical of most English William and Mary scrutoirs (figs. 3, 5, 10).

The bold, jutting cornice, strong Roman ovolo base molding, and large ball feet on the Brinckerhoff scrutoir give it a commanding architectural presence and relate it directly to that most iconic of New York Dutch forms, the kast (fig. 19). This powerful baroque combination was masterfully blended into the overall design of the scrutoir with the express purpose, it seems, of bending a stylish Anglo furniture form to the will of the local vernacular. Curiously, however, the profiles used in the cornice, actually the entire entablature, on the Brinckerhoff scrutoir do not follow the usual sequence found on late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century New York Dutch kasten. Instead, the entablature appears to be an outsize version of those found on English William and Mary cabinets and scrutoirs, which typically utilize either the Ionic order or a combination of the Doric and Ionic orders. The latter holds true for the Brinckerhoff scrutoir (fig. 20), its cornice being composed of a deep cavetto with a flat corona that extends below the soffit to form a drip edge in the same manner as a cornice shown in a plate from Vignola’s Cinque ordini d’architettura, which depicts a capital and full entablature in the Doric order from the Teatro di Marcello in Rome (fig. 21). The frieze on the Brinckerhoff scrutoir comprises an ovolo, a cavetto, and a wide pulvinated section, like that in a plate from a seventeenth-century English translation of Palladio’s Il primo libro dell’architettura (fig. 22). While it seems unlikely that the maker of the Brinckerhoff scrutoir or his client were able to consult either of these architectural treatises, his manipulation of a classical Roman entablature to satisfy a New York Dutch aesthetic underscores the extent to which prescribed European patterns and forms could be subject to dynamic and unexpected changes in the hands of creative colonial American craftsmen.

The molding profiles in the entablature on the Brinckerhoff scrutoir (with the exception of the ovolo and cavetto profiles in the frieze, which were shaped by a scratch stock) were formed by a combination of hollow and round planes. Even the slightly odd-looking scotia profile below the pulvinated frieze, which serves as the architrave in the entablature (fig. 20), was made with a round plane. This use of hollow and round planes and a scratch stock suggests that the maker of the Brinckerhoff scrutoir did not have access to the types of architectural molding planes used to fashion classical Roman profiles like those on the Child and Evans scrutoirs and also that he was trained in the New York Dutch tradition of joinery. The technique of forming the profiles of a cornice on a single board with hollow and round planes and then installing it at an angle on separate dovetailed cornice boxes to approximate architectural mass is referred to as “pitched-plank” or “pitched-line” construction and is highly characteristic of New York kasten as well as fixed architectural trim in early New York Dutch house interiors. The Brinckerhoff scrutoir, unlike its New England and Pennsylvania counterparts, utilizes this pitched-plank construction technique and features the same distinctive type of dovetailed cornice box as seen on the kasten but not employed on either the Evans or Child scrutoirs (figs. 23).[9]

The New York Dutch design features that so powerfully inflect the Brinckerhoff scrutoir represent just half of the cultural borrowing that makes it one of the most thoroughly creolized pieces of early American furniture. The other half, and undeniably its most resplendent, is its wholesale appropriation of the line-and-berry inlay tradition of southeastern Pennsylvania. Perhaps the Brinckerhoff scrutoir is ornamented this way because an itinerant specialist craftsman from Pennsylvania was in or around Newtown or Flushing, Long Island, and was commissioned to undertake the work. Or perhaps a local craftsman and/or his client saw this relatively simple method of compass-work decoration on a box, cabinet, or other piece of line-and-berry inlaid furniture brought to western Long Island by a Pennsylvania family that resettled there or that perhaps was sent there as a gift, and then tried to replicate it. The minutes of Quaker Meetings in New York suggest that members were quite mobile and moved with some frequency in both directions between western Long Island and southeastern Pennsylvania. There also were numerous marriages between Quakers from Flushing and Newtown and those from southeastern Pennsylvania. In one of the few such references that record the name of a recognized furniture maker, David Humphrey of Merion, Pennsylvania, appears in the minutes of the Flushing Quaker Meeting on March 20, 1727/28, when he married Elizabeth Ford, the daughter of Flushing joiner Thomas Ford (d. 1743). Humphrey was in Flushing well before that date, having been recorded in the minutes on August 13, 1724, as “being home to visit his parents.” Could Humphrey have been Ford’s apprentice and then, in time-honored fashion, married his master’s daughter? There is also reference to the marriage of Sarah, daughter of Edward Burling (1639–1697), progenitor of the Burling family of wheelwrights, carpenters, joiners, and cabinetmakers in America, to John Way, who was granted a certificate from the Newtown, Long Island, Quaker Meeting to move with his wife to Pennsylvania on March 2, 1718/19. Tantalizing as these Quaker Meeting records might be, however, it has not been possible to determine from them the presence of a Quaker furniture craftsman or line-and-berry inlay specialist from southeastern Pennsylvania on western Long Island in the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century.[10]

The Brinckerhoff scrutoir’s early date of manufacture, sometime between 1700 and 1725, places it in rare company as far as Pennsylvania line-and-berry decorated furniture made in that date range is concerned, which makes it difficult to draw comparisons with the patterns and techniques used there. The earliest known Pennsylvania example is a walnut chest of drawers with a top inlaid with the initials “I” and “B,” the date “1706,” and two single berries and two clusters of four berries within an elliptical reserve of light-wood stringing. The only point of comparison between the inlay on this chest of drawers and that on the Brinckerhoff scrutoir is the somewhat sloppy way the berries are cut and set into the ground. The next earliest dated example is a magnificent inlaid oval table with falling leaves that has the initials of James and Eliza Bartram and the date “1725” set within a cartouche of light-wood stringing and curving inlaid tendrils that terminate in small pointed leaves and a single cluster of three berries. The stringing and other inlay are very fine and more competently executed overall than on the Brinckerhoff scrutoir. This same quality workmanship is found on an undated walnut chest of drawers (fig. 24) that, based on its early two-part design, may have been made before 1725. Like the Brinckerhoff scrutoir, it has clusters of four berries and occasionally even five (fig. 25), which, in a way, transform the pattern from line-and-berry to vine-and-flower. On the Brinckerhoff scrutoir this decoration is especially pleasing in the pulvinated frieze (fig. 26), where it reads like a delicate floral valance. Tiny flowers sprout among the larger ones, as they do on some of the interior drawers, giving the overall composition a more naturalistic effect. The random mixing of flowers with dark centers and light-wood petals and vice versa enhances this effect further still (fig. 27). By comparison, the line-and-berry or vine-and-flower inlay on the drawer fronts of Pennsylvania furniture more often appears to be laid out in bilaterally symmetrical patterns. This difference is clearly visible when one compares the inlaid drawer fronts in the base of the Brinckerhoff scrutoir with those in the two-part chest of drawers (figs. 24, 26).

An inlaid box, chest of drawers, or other piece of southeastern Pennsylvania furniture that is a more immediate cognate of the Brinckerhoff scrutoir, if indeed one ever existed, has yet to be found. It is possible that the inlay on the Brinckerhoff scrutoir was done by an immigrant Welsh craftsman who made his way to western Long Island, Wales being the place credited as the source for this type of decoration on southeastern Pennsylvania furniture by the leading scholar on line-and-berry inlaid furniture. If this were the case, however, why is it that no other example of New York furniture with this type of decoration is known? At least for the present, the most likely scenario is that the decoration on the Brinckerhoff scrutoir is anomalous, a one-off, executed either by a local craftsman working outside the tradition of southeastern Pennsylvania line-and-berry furniture or by a Pennsylvania craftsman following designs prescribed by a patron. The more naturalistic pattern of the inlay on the Brinckerhoff scrutoir as well as the inelegant way the flower petals and centers occasionally mash up against each other provide circumstantial evidence to support the conclusion that the person who executed this inlay was not proficient at his craft. It can be said with certainty, however, that the person who inlaid the Brinckerhoff scrutoir lacked neither ambition nor patience. Slightly more than one thousand circular reserves had to be cut into its surface and, in turn, more than one thousand berries had to be cut to fill them, not to mention the yards of stringing that had to be made and inlaid on a radius. The survival of some trial excavations into the back surface of one of the drawer fronts provides evidence of the technique used to form these circular holes (fig. 28), which were not, as might be assumed, made with a boring tool. Instead, they appear to have been cut with an incannel firmer gouge, a type of gouge that is ground on the inside to give an outside cutting edge. This technique may eventually provide sounder evidence that the inlay on the Brinckerhoff scrutoir was done by a local craftsman, especially if it can be proven that the round holes on Pennsylvania line-and-berry inlaid furniture were formed by a brace and bit.[11]

Iconography: The Ark of a Covenant

The naturalistic decoration that covers the entire front surface of the Brinckerhoff scrutoir, both inside and out, is reflective of the baroque taste for rich, complex surfaces and overall naturalistic patterns of vines, flowers, and leaves found more often on painted New England furniture of the first quarter of the eighteenth century and believed to be inspired by imported English ceramics and Indian cotton textiles. The ornamental composition on the fall front (fig. 29), a tree of life within a patterned border, is typical of Indian cotton chintz palampores, which may very well have served as the basis of its design. But there is more to the ornamental program on the Brinckerhoff scrutoir than can be perceived in a frontal view. Published fully six times in the twentieth century in exhibition catalogues and histories of American furniture, the Brinckerhoff scrutoir has only been illustrated turned at a slight angle to the viewer with its fall front in the open position. The striking and unusual ornament on its sides has until now never been fully seen, nor, even more surprisingly, did it elicit any interest on the part of the authors who published the scrutoir. Inlaid into the upper and lower case of the scrutoir, identical on each side, are two whimsical anthropomorphic figures (fig. 30), laid out with a compass and drawn in light-wood stringing. What do these figures represent? Perhaps the so-called Green Man, a pre-Christian folklore figure who symbolized fertility or the spirit of nature and finds expression later in carved architectural ornament in medieval and Renaissance churches? Possibly. Yet when considered in combination with the tree of life pattern on the fall front, an alternative interpretation emerges that centers on covenant theology, a concept or system of belief developed by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Reformed Protestant theologians to describe the way that God enters into fellowship with the faithful. Unlocking the iconography of the ornament on the Brinckerhoff scrutoir relies on establishing male and female identities for the inlaid figures on the sides. The figure in the upper case (fig. 31) has a round face with inlaid berries and compass-curved stringing that serve as its eyes, nose, and mouth. The crossed tendrils and flowers at the top and those sprouting at the sides make it appear as if the figure is wearing some type of floral bonnet or flowers in its hair, while the curved tendrils that form the lower part of its body, considerably broader and more elaborate than on the figure below, suggest the outline of a wide flowered skirt. The figure below, also whimsically drawn, nonetheless is far less fancy. It would seem fair to say, therefore, that the one in the upper case has more attributes one might describe as feminine, while the inlaid figure in the lower case, owing to its relative plainness, could be interpreted as male. Male and female figures, a stylized tree bearing fruit or flowers, a trellis of flowering vines in the pulvinated frieze, and abundant vines and flowers over all the base drawers and the interior compartment of the upper case: Could these have been intended to create a composite picture of Adam and Eve and the tree of life, or the tree of knowledge of good and evil, in the Garden of Eden?

The pillars of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Dutch Reformed orthodoxy were the covenant of works and the covenant of grace. The former was defined by Dutch Reformed theologian Wilhelmus a’ Brakel (1635–1711) as an agreement between God and Adam in which God promised Adam eternal salvation on the condition of obedience and threatened eternal death for disobedience. Adam and Eve broke this covenant by eating the forbidden fruit from the tree of knowledge of good and evil and were expelled from the Garden of Eden. God, in his infinite mercy, however, offered Adam and Eve and the elect a second chance through the covenant of grace, which promised eternal salvation on the condition of maintaining faith in God. Images of Adam and Eve in paradise and their expulsion from the Garden of Eden were ubiquitous in the visual culture of the Low Countries in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as evidenced by such works as a series of six prints titled The Story of Adam and Eve (fig. 32), by Jan Saenredam (ca. 1565–1607), or in the engravings used to ornament the borders of Dutch Bible maps (fig. 33) by Amsterdam engraver Nicolaes Visscher I (1618–1679). Religious art decidedly had a place in the homes of the New York Dutch. Take, for instance, the Dutch biblical tiles that lined the back walls of their jambless fireplaces, or the scripture paintings based on Dutch engravings by such artists as Gerardus Duyckinck I (1695–1746) that graced their walls (fig. 34). Dutch Bibles were kept out for reference and display sometimes on a Bible desk or bybellessenar, a kind of a desk on frame, similar to the example shown in figure 7 that has a hinged, slanted top with a book ledge at the bottom that kept a Bible from sliding off. Two of the possible original owners of the Brinkerhoff scrutoir, Abraham Jorise Brinckerhoff and his grandson Teunis, were elders in the Dutch Reformed Church and could have been motivated by their faith to commission an iconographic program based on covenant theology.[12]

At the risk of extending this religious interpretation too far, it nonetheless should be pointed out that the Brinckerhoff scrutoir is primarily constructed of cedar, a tree and timber mentioned frequently throughout the Old Testament: “The righteous will flourish like a palm tree: he shall grow like a cedar in Lebanon” (Psalms 92:12); “Thus saith the Lord GOD; a great eagle with great wings, longwinged, full of feathers, which had divers colours, came unto Lebanon, and took the highest branch of the cedar” (Ezekiel 17:3); “Now Hiram the king of Tyre had furnished Solomon with cedar trees and fir trees, and with gold, according to all his desire, that then king Solomon gave Hiram twenty cities in the land of Galilee” (1 Kings 9:11). Just as in biblical times, cedar was admired in England and colonial America for the “Goodness” of its “Grain, Smell and Colour” as well as its “everlastingnesse,” or rot resistance, and the ability to protect linen and woolen cloth from “Moths” and “Corruption.”[13]

Two types of cedar were detected by microanalysis in the Brinckerhoff scrutoir: the genus Juniperus for the front of one of the square inlaid drawers in the interior compartment; and Chamaecyperis thyoides, Atlantic white cedar, for the right side of the top drawer in the bottom section. The microanalysis for the drawer front in the interior compartment was conducted at Roderic H. Blackburn’s request by Gordon Saltar at Winterthur. In a note to Blackburn dated February 1, 1975, Saltar suggested that the wood was either J. bermudiana or J. virginiana. The range for Juniperus virginiana extended from New England to Florida, so if this is the wood used on the interior drawer fronts, in addition to, as it appears by eye, on the veneered fall front and the fronts of the deep drawers in the lower case, the solid case sides, moldings, and turned ball feet, then it could have been felled and processed locally or imported by ship from the Carolinas, Virginia, or Pennsylvania. And of course, if it is Juniperis bermudiana, it likely came from the island of Bermuda. By eye, the red-brown color and satiny sheen of the narrow widths of cedar used to veneer the fall front and the fronts of the drawers in the lower case, as well as the solid board sides of the case, all the moldings, and the turned ball feet suggest that all of these are Juniperus as well.

Aside from the Brinckerhoff scrutoir, early New York furniture made of cedar is virtually unknown. The fact that the fall front and the faces of the drawers in the lower case of the Brinckerhoff scrutoir are covered with multiple swaths of cedar veneer and that the sides of the upper and lower cases are made of multiple boards of lesser-quality wood (fig. 30) indicates that the maker of the Brinckerhoff scrutoir was working with a limited supply of fairly narrow cedar boards. Veneering may also imply the preciousness of a commodity in relatively short supply. In 1670 English diarist John Evelyn described Juniperus bermudiana, Bermuda cedar, as “this precious material” and went on to suggest that “our more Wealthy Citizens of London, now Building, might be encouraged to use it in their Shops; at least for Shelves, Comptoires, Chests, Tables, Wainscot, &c. It might be done with moderate Expense, especially, in small proportions and in Faneering, as they term it.” It is intriguing to consider the possibility that the Brinckerhoff who commissioned this scrutoir may have provided the Juniperus used to build it in the knowledge that he was using a rare, highly desirable commodity, or because it resounded for him with Old Testament meaning.[14]

The only early baroque veneered case furniture that unequivocally can be said to come from New York are two kasten made at Albany between 1710 and 1740. Constructed principally of solid bilsted, or gum as it is called today, these kasten have complex paneled doors with applied perimeter moldings, projecting applied blocks at the center, and, in between, flat mitered swaths of gumwood veneers. On one of these Albany kasten (fig. 19) the doors are composed of vertically oriented, 3/4-inch-thick, white pine boards to which the perimeter moldings, central blocks, and mitered veneers are applied. The other has a frame and panel assembly beneath the applied moldings and veneers. The door and side panels on this kast are ledger-rabbeted, as are the side panels on the kast with the board cores. Ledger-rabbeted panels are a labor-intensive method of construction used to create a flush surface between the panel and frame for the application of veneers. According to authors Robert F. Trent, Alan Miller, Glenn Adamson, and Harry Mack Truax II, this technique offers qualified evidence that these Albany kasten were made by an immigrant ébéniste, probably from the Netherlands, “who used American primary woods as he would have used exotics in Europe.” The core of the fall front on the Brinckerhoff scrutoir is a frame-and-panel assembly constructed of chestnut with a ledger-rabbeted central panel made of several edge-joined boards. These boards have separated over time owing to shrinkage, causing the vertical cracks, now poorly filled, that mar the surface of the fall front (fig. 29). The Albany kasten and the Brinckerhoff scrutoir are also closely related through the similarities of the profiles of their ovolo base moldings and turned ball feet (compare figs. 19 and 27). Trent and his fellow authors cite Italian Renaissance furniture as the precedent for the turning profile of the feet on the kast illustrated in figure 19, with its upper ovolo, stiff tapering neck, slightly flattened ball, and flaring base, and suggest that these feet may be the work of a specialist turner. Explaining the precise relationship between these kasten and the Brinckerhoff scrutoir, which nonetheless appear to come from different shops, is difficult. But it does seem to add weight to the theory that the maker of the Brinckerhoff scrutoir was trained in a shop in which Continental European, most likely Dutch, furniture-making traditions held sway.[15]

Despite these efforts to explicate the Brinckerhoff scrutoir, much about it remains shrouded in mystery. Long Island has produced other furniture enigmas as well. Take, for instance, the remarkable seventeenth-century two-door inlaid oak wardrobe in the Winterthur collection originally owned by the Hewlett family of Merrick, which continues to confound furniture historians as to its origins and its relationship to other seventeenth-century New York oak furniture. Objects as rich and complex as these from the crossroads of Anglo-Dutch culture on western Long Island are what makes early New York furniture at once so maddening and endlessly fascinating.[16]

T. Van Wyck Brinkerhoff, “Joris Dircksen Brinckerhoff’s Secretary,” in Roeliff Brinkerhoff and T. Van Wyck Brinkerhoff, The Family of Joris Dircksen Brinckerhoff, 1638 (New York: Richard Brinkerhoff Publisher, 1887), p. 114. Despite the claim of the scrutoir’s being “given by repeated wills to the sons of the name,” only two Brinckerhoff wills and one inventory in the line of descent could be located: the will of Joris A. Brinckerhoff (1664–1729; see note 7 below), which does not mention the scrutoir; the will of George Brinckerhoff (1726–1797), probated February 22, 1798, which mentions a “chest of drawers” given to his son George Brinckerhoff (1765–1834), recorded Book A, p. 333, file box 3377, Dutchess County, Surrogate’s Court, Poughkeepsie, New York; and the inventory of Tunis Brinckerhoff dated February 14, 1874, which lists “One old secretary or Desk given by will of Testator to T. V. W. Brinckerhoff,” recorded Book 2, p. 452, file box 7666, Dutchess County Surrogate’s Court, Poughkeepsie, New York. T. Van Wyck Brinkerhoff used the scrutoir for many years in his family home in East Fishkill, New York, where it was photographed for inclusion in his 1887 family history. The house, the earliest part of which dates to 1751, is known as the Storm-Adriance-Brinckerhoff House and is listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, NRHP Reference #08000581. It was acquired by George Brinckerhoff (1765–1834) in 1794. T. Van Wyck Brinkerhoff’s daughter Julia Hunter Brinkerhoff Clapp (1868–1937) kept the house in the family until 1930. In 1936 she lent the scrutoir to the Museum of the City of New York, which eventually acquired it in 1945. For the origins of the Brinckerhoff family in the Netherlands, see James Riker Jr., The Annals of Newtown in Queens County, New York (New York: published by D. Fanshaw, 1852), p. 291. For their kind assistance in the preparation of this article, I would like to thank Christine Ritok of the Museum of the City of New York; James Tottis; Samantha DeTillio; Catherine Mackay, American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Mark Anderson, Winterthur Museum; Wendy Cooper; Jackie Killian; Bill DuPont; Gavin Ashworth; Luke Beckerdite; Olaf Unsoeld; and especially Alan Miller for his interest, insight, and support.

Dennis Carr, “Recent Discoveries in Rhode Island Furniture,” Antiques 181, no. 1 (January–February 2014): 217. Irving Whitall Lyon, The Colonial Furniture of New England: A Study of the Domestic Furniture in Use in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, & Co., 1891), pp. 116–18, for use of a variety of terms for writing desks in colonial inventories. The New World of Words: or, Universal English Dictionary, compiled by Edward Phillips (London: printed by H. Rhodes and J. Taylor, 1706) as cited in Lyon. Luke Vincent Lockwood, Colonial Furniture in America, 3rd ed. 2 vols.(New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1926), 1: 218.

Lockwood, Colonial Furniture, 1: 218. Ruth Piwonka, “New York Colonial Inventories: Dutch Interiors as a Measure of Cultural Change,” in New World Dutch Studies: Dutch Arts and Culture in Colonial America, 1609–1776, edited by Roderic H. Blackburn and Nancy A. Kelley (Albany, N.Y.: Albany Institute of History and Art, 1987), p. 74. Esther Singleton, The Furniture of Our Forefathers (New York: Doubleday, Page and Company, 1900), p. 274.

Singleton, Furniture of Our Forefathers, p. 269. Jonathan L. Fairbanks and Elizabeth Bidwell Bates, American Furniture, 1620 to the Present (New York: R. Marek, 1981), p. 58. Reinier Baarsen, Philip M. Johnston, Gervase Jackson-Stops, and Elaine Evans Dee, Courts and Colonies: The William and Mary Style in Holland, England, and America (New York: Cooper-Hewitt Museum, 1988), p. 154. Dean F. Failey, Long Island Is My Nation: The Decorative Arts and Craftsmen, 1640–1830, 2nd ed. (Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities, 1998), pp. 11–15.

Riker, Annals of Newtown, pp. 290–91.

Ibid., pp. 292, 339. Brinkerhoff and Brinkerhoff, Family of Joris Dircksen Brinckerhoff, p. 154.

Riker, Annals of Newtown, p. 293. Brinkerhoff and Brinkerhoff, Family of Joris Dircksen Brinckerhoff, p. 154, where it is stated that in the years 1675 and 1676 there was but one person who paid a higher tax in the town of Flatbush than Abraham Brinckerhoff. Will of Joris A. Brinckerhoff, November 6, 1729, File no. 841 series J0038-92, microfilm roll 5, New York State Archives, Albany, New York.

Brinkerhoff and Brinkerhoff, Family of Joris Dircksen Brinckerhoff, p. 114.

Robert F. Trent, Alan Miller, Glenn Adamson, and Harry Mack Truax II, “High Craft along the Mohawk: Early Woodwork form the Albany Area of New York,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 119–20.

William Wade Hinshaw, Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, 6 vols. (Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1969), 3: 55, 177. For Thomas Ford, see Failey, Long Island Is My Nation, p. 276. Cross-referencing the names of joiners from Chester County, Pennsylvania (see Margaret Berwind Schiffer, Arts and Crafts of Chester County, Pennsylvania [Exton, Pa.: Schiffer, 1980]), with Hinshaw’s survey of New York Quaker Meetings failed to reveal names of any carpenters or joiners who moved from Chester County to Newtown or Flushing. Likewise, the list of woodworking craftsmen listed in appendix 1 in Failey failed to reveal any movement of Quaker craftsmen from Chester County to Long Island.

Lee Ellen Griffith, “Line and Berry and Inlaid Furniture: A Regional Craft Tradition in Pennsylvania, 1682–1790” (Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1988), pp. 157–82. Griffith (p. 175) states that the “existence of an inlaid fall front desk (the Brinckerhoff scrutoir), made in New York in about 1700, confirms that these types of inlay patterns (line and berry inlay on Pennsylvania furniture) had their roots in Dutch, or nearby Flemish, culture.” If this assessment is true, then why is there not any other inlaid New York furniture like the Brinckerhoff scrutoir, not to mention pieces from Flanders and the Netherlands? I would like to thank Alan Miller for his keen observation that the holes in the back face of the drawer in the Brinckerhoff scrutoir were made with an incannel gouge. One also sees slightly irregular countersunk holes for nails, possibly formed with an incannel gouge and plugged with face-grain wood, in the sides and cornice of some kasten from western Long Island. A kast from Kings County, New York, is a good example of this. Dennis A. Carr, “Going Dutch: The Mott/Willis Family Kast,” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin 2003 (2003): 100–103 (acc. 2000.29.1).

For a discussion of the covenant of works and covenant theology, see Shane Lems, “The Covenant of Works in Dutch Reformed Orthodoxy,” Outlook 57, no. 6 (June 2007): 13–18, reprinted at http://www.reformedfellowship.net/articles/lems_cov_jun07_v57_n06.htm. Roderic H. Blackburn and Ruth Piwonka, Remembrance of Patria: Dutch Arts and Culture in Colonial America (Albany, N.Y.: Publishing Center for Cultural Resources for the Albany Institute of History and Art, 1988), p. 178.

http://classic.net.bible.org/dictionary.php?=Cedar. www.artbible.info/concordance/c/7400-1.html. Adam Bowett, Woods in British Furniture-Making, 1400–1900: An Illustrated Historical Dictionary (Kent, Eng.: Oblong Creative, in association with Royal Botanic Gardens, 2012), p. 276 n. 34, p. 281 n. 57.

Neil D. Kamil, Winterthur Fellow, to Margie Sterns, Museum of the City of New York, November 28, 1977. Gordon Saltar, Winterthur, to Roderic H. Blackburn, Albany Institute of History and Art, February 1, 1975, accession files for 45.112 a–c. The joints between the two pieces of veneer used on the drawer fronts are clearly visible. Extensive infills running the full length of two of the four vertical joints on the fall front make the precise location of the joints on the panel impossible to determine. The substrate beneath the veneers on the fall front is chestnut, and on the base drawers it appears to be Juniperus. John Evelyn, SYLVA, or a Discourse of Forest Trees and the Propagation of Timber in His Majesties Dominions (London, 1670), pp. 120–21, as cited in Bowett, Woods in British Furniture-Making, p. 281.

Trent et al., “High Craft along the Mohawk,” pp. 115–18.

For the Hewlett family wardrobe, see Failey, Long Island Is My Nation, pp. 36–37.