(Left) Edward Steichen, Portrait of Charles Lang Freer (1854–1919), New York, New York, 1916. Black-and-white platinum print. (Charles Lang Freer Papers, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives, Gift of the Estate of Charles Lang Freer, FSA A.01 12.01.1.) (Right) C. T. Loo (1880–1957), at C.T. Loo et Cie, Paris, France, 1909. Black-and-white silver gelatin print. (Loo Family Photographs, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., Gift of Janine Pierre-Emmanual, FSA A2010.07.)

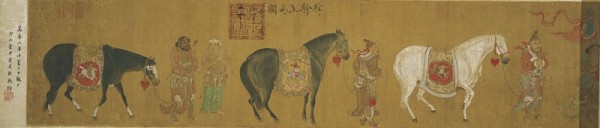

Central Asians Presenting Tribute Horses, handscroll, traditionally attributed to Han Gan (ca. 715–after 781). Ink, color, and gold on silk, 12 3/16 x 75 7/8 in. (Courtesy, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1915.16.) Charles Freer purchased this in San Francisco in 1915 from the L.C. Pang Collection (Pang Lai-chen) (Pang Yuanji) (1864–1949), Chekiang, China, through C.T. Loo.

Bowl, Longquan, Zhejiang province, China, early fifteenth century (Ming dynasty). Stoneware with celadon glaze. H. 3 3/16". (Courtesy, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F19163a–b.) Charles Freer purchased this from Lai-Yuan and Company, New York, in 1916.

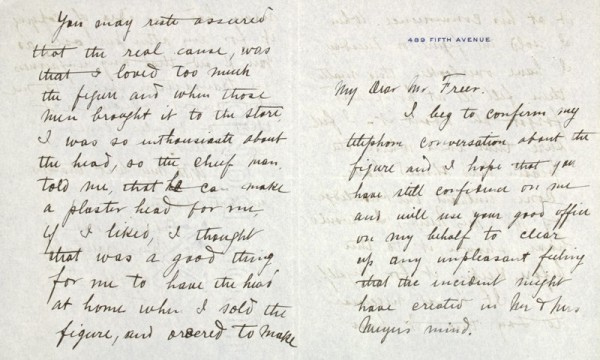

Letter from C. T. Loo to Charles Lang Freer, March 16, 1916, in which Loo explains to Freer the reason he copied a Chinese artifact he sold to the Meyers. Charles Lang Freer Papers, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., Gift of the Estate of Charles Lang Freer.

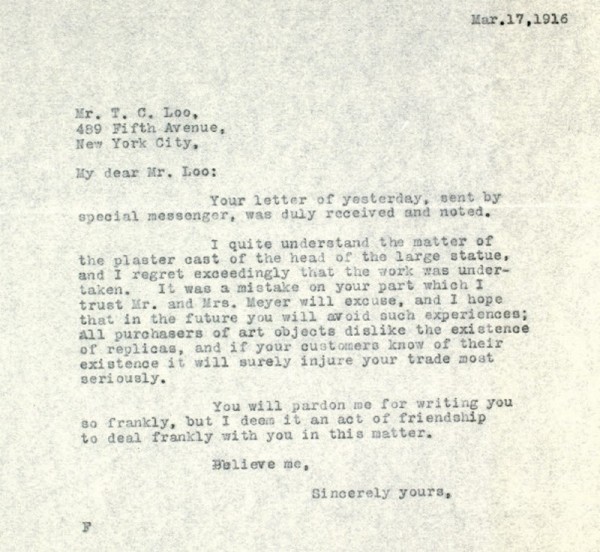

Response from Charles Freer to C. T. Loo [erroneously spelled T. C. Loo], March 17, 1916, regarding the copied head sold to the Meyers.Charles Lang Freer Papers, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., Gift of the Estate of Charles Lang Freer.

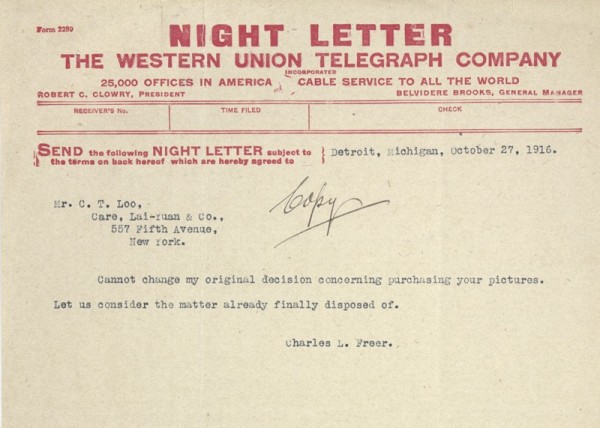

Telegram from Charles Lang Freer to C. T. Loo, October 27, 1916, telling him that he would not purchase the pictures. Charles Lang Freer Papers, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., Gift of the Estate of Charles Lang Freer.

C.T. Loo (Loo, Ching-tsai, 1880–1957), the premier dealer of Chinese porcelain in America during the first half of the twentieth century, is a controversial figure. While he may have preserved Chinese artifacts that might have been destroyed during volatile war years in China, he simultaneously sold his country’s treasures, some of which were literally chiseled from their in situ locations. Whether Loo was Savior or Satan for China’s cultural artifacts, then, depends on one’s perspective.

Loo’s business dealings with his American clients (and perhaps his European ones as well, but I do not have those records) are also troubling and controversial. When I first wrote about him in regard to Eli Lilly (1885–1977)—CEO of the pharmaceutical firm Eli Lilly and Company from 1932 to 1948 and purchaser of Chinese art from Loo in the second half of the 1940s[1]—I was more forgiving than I am today. This was because I had not yet read Loo’s correspondence with Charles Lang Freer (1854–1919), a collector of Asian porcelain and respected turn-of-the-century American industrialist. In reviewing those communications, I found that Freer had tried to mentor Loo early in his selling career in America regarding the forthrightness and honesty expected of American art dealers, yet he met with little if any success. Ultimately Freer was sufficiently repelled by Loo’s continued shenanigans that he gave up on the man. I found this riveting, because some thirty years later Eli Lilly became disenchanted with Loo for similar reasons. Lilly noticed that Loo charged three to four times what he had sold the same objects for only a few years earlier. Loo had continued to be a “bad boy” dealer despite Freer’s considerable efforts to teach him American standards and ethics. It was the perceived financial unfairness of the dealer by buyers Freer and Lilly that led each to distance himself from Loo.

Early Interactions

Although a large number of objects at the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., were purchased from CT Loo and Company, Charles Freer’s direct purchases from Loo were far fewer.[2] In part this was because Loo did not begin to trade in the United States until 1915, when he was thirty-five and Freer was sixty-one (fig. 1). Freer died four years later, in 1919.

By the time Loo set up his establishment in New York City, he already had a shop in Paris and offices in Shanghai and Beijing.[3] He moved to the United States to escape the turbulence in Europe due to World War I, and in 1915 opened his first showroom in Manhattan, at 489 Fifth Avenue; by June 1916 he had moved to 557 Fifth Avenue.

Freer met Loo for the first time in 1915 at the Panama Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, and it was there that he purchased thirteen paintings from the dealer (fig. 2).[4] Loo fostered communications between the two, knowing that Freer’s wealth and power meant that he could buy for himself and also introduce Loo to other important and wealthy potential customers. Charles Freer was already a seasoned collector with a discerning eye when he met Loo (fig. 3). Freer was considered an expert in Asian art, having traveled to Asia on five occasions—the first in 1892—to buy objects and to increase his knowledge about Asian art. He was, in fact, arguably more knowledgeable than Loo, who was twenty-six years younger and had traded Chinese art only since 1903—a far shorter period than Freer.[5]

Freer as Mentor

Throughout 1916 Freer expedited transactions for Loo. For example, on June 10, 1916, Loo wrote to Freer and thanked him for facilitating a sale to the well-known financier J. P. Morgan. Six days later, on June 16, Freer assisted Loo with a sale of a bronze to his influential and wealthy friends Eugene and Agnes E. Meyer.[6] Eugene was a multimillionaire investor, among other successful accomplishments, and his sometimes flamboyant wife, Agnes, was a journalist and a good friend of Freer. However, an awkward and delicate situation arose for Freer. Loo sold a piece to the Meyers, but unbeknownst to them had a duplicate made for himself. Evidently the couple found out and Loo was fearful of their reaction. He wrote to Freer on March 16, 1916, asking him to intervene with any “unpleasant” feelings the Meyers might have. Loo explained his action by claiming that “I loved too much the figure” (fig. 4).

Although Freer was kind and helpful in his return letter the following day, he was also firm and direct (fig. 5):

I quite understand the matter of the plaster cast of the head of the large statue, and I regret exceedingly that the work was undertaken. It was a mistake on your part which I trust Mr. and Mrs. Meyer will excuse, and I hope that in the future you will avoid such experiences; all purchasers of art objects dislike the existence of replicas, and if your customers know of their existence it will surely injure your trade most seriously.

After this jolt to the otherwise harmonious relationship between Freer and Loo, the summer of 1916 passed quietly between the two. As fall neared, however, it was business as usual. Loo began asking Freer for advice and favors. In a letter dated August 14, 1916, he wrote to Freer about a Japanese plaster lacquer sitting statue of the Tempio period he had seen in Paris. He said he was considering offering 20,000–25,000 francs for the object, but first wanted Freer’s advice. Did Mr. Freer think Loo should risk buying the piece even if Freer would not add it to his own collection?

Freer replied five days later, on August 19, and told Loo that the object was similar to one he already owned that was on exhibit in Cleveland, Ohio. He had purchased it for $600, delivered to his residence in Detroit, “some years ago.” He added that a purchase price of 20,000 francs (roughly $3,333 in 1916 currency) was considerably more, but conceded that the interest in oriental art in America was such that even 30,000 francs might be justified. Freer informed Loo that the Cleveland, Minneapolis, and Philadelphia museums did not have this lacquer statue and might be interested in buying the piece. It is clear that Freer continued to be friendly and helpful toward Loo. However, the next transaction between the two marked the beginning of the end of their relationship.

A Potential Deal

On September 30, 1916, Loo sent to Freer a catalog of Chinese paintings gathered by a Mr. Kwen. Upon receipt, Freer was enthusiastic: “I want to see the paintings immediately after their arrival and should like to be considered a purchaser of some if not all of the collection. Perhaps you and I can arrange a satisfactory price for the entire lot, but concerning this we can talk fully during your coming visit . . . .” This must have pleased Loo enormously. He replied on October 10, expressing thanks to Freer for his constant courtesy and kindness. He also sent tea and flattered Freer: “I hope that you are enjoying with the paintings as much as I have enjoyed the beautiful sceneries of your true Sung hermitage of a pure and righteous learned philosopher of the 20th century in the New World.” Loo was surely anticipating a quick and profitable sale.

But, there was a hitch. After seeing the paintings in person, Freer reconsidered. On October 13, Freer wrote and thanked Loo for the tea but also wavered on his earlier thought of buying the paintings outright: “Some of the paintings are very much restored and their aesthetic interest is sadly injured. . . . This letter, however, is simply to report progress and later I will write you fully and frankly.” Presumably there were verbal negotiations between the two men about the price of the paintings, but what is known securely comes only from written documentation near the end of their communications.

Unfairness Perceived

Loo, trying to negotiate a better price, wrote to Freer on October 23 and said his friends in China—perhaps what we in the United States would call “pickers”—were not able to accept Freer’s offer but would make a “special price” for him of $60,000. This rich sum, well over a million dollars in today’s currency, apparently did not suit Freer and he must have indicated to Loo verbally that he would not pay it. Loo sent a cable to Freer the next day, October 24, and used capital letters to emphasize the urgency: “PLEASE DO ME FAVOR SEND PAINTINGS TO YOUR POSSESSION AND LET ME HAVE TIME TO WORK AGAIN.” A handwritten note by Freer on Loo’s telegram tells the remainder of the story: “Answered Oct. 24th Declining to further care for paintings and ending all negotiations for their purchase—both by wire and letter—.”

Freer also wrote to his friend Agnes Meyer that day: “This broke the camel’s back! The pictures were instantly returned to Loo not-withstanding his protest—and so far as I am concerned the book covers are slammed shut.” It is clear that Freer’s decision was final, but Loo was not giving up. He knew that if he did, he would lose not only this sale, but almost certainly Freer’s future help. Loo responded with a handwritten note to Freer the same day, Oct. 24: “I feel quite upset about the difference in the price on the paintings, and have failed to give you a satisfactory reply. . . . I feel sure your estimation is the proper value and Mr. Kwen must have paid too much on certain pictures.”

Loo reinforced this the next day, October 25, in another letter to Freer: “For our past good relations would you do me a personal favor to take the collection at the price you figured me and give orders for the exhibition for the sake of public interest, and our future success which is entirely depending on you and let me still rely on your help.”

Freer was not moved by Loo’s pleas, which is painfully clear in his night telegram of October 27 (fig. 6): “Cannot change my original decision concerning purchasing your pictures. Let us consider the matter already finally disposed of.” Freer explained his decision in detail to Loo in a letter that same day. The content of that letter is important because it clarifies how inconsistent Loo was in his price negotiations for the paintings. In fact, when Loo thought he would lose the sale, he decreased the price to less than he indicated earlier that the paintings had cost. Freer wrote:

I have given considerable thought to the matter and am now fully convinced that in deciding not to buy the collection or to consider the obsurd [sic] advances which you proposed, I did exactly right . . . . I cannot understand even today that if I were to accept the pictures at my prices, as suggested in your letter of the 25th, that your partners in Shanghai would be satisfied, particularly when you ask to have certain numbers returned to you, because my price is, I understand, less than you paid for them, as you know full well, I want no financial favor from you or your partners. I am always ready and willing to pay what I consider a fair value for objects bought from you, but I will not be a party to excessive profits, nor will I take things from your concern at less than cost . . . .”

Although Loo contacted Freer again, apparently he received no reply. Loo’s mentor was finished with him.

This story is even more illuminating when compared with Loo’s interaction with Eli Lilly decades later. During 1947–48, a time when Lilly was purchasing from him, Loo used the same tactics he had with Freer, showing how little he had learned, if anything, from Freer’s counsel. Yet Lilly similarly reduced his interactions with Loo, perceiving, as had Freer, inconsistencies in Loo’s behavior.

Beyond Loo

Although most of the antique dealers with whom Freer dealt were to his liking, this was not the first time he had been made wary enough to withdraw from a potential deal.[7] During his 1907 trip to Asia, he discovered that Japanese dealers were trying to dupe him by placing their wares in a temple rather than in their shops. When Freer visited the holy place, he was told everything was for sale. He thought the priests were the sellers. Freer studied the objects for two days and only when he was ready to buy did he learn that the priests were actually dealers in disguise. This deception angered him: “To protect myself against contemplated conspiracies, which I quickly discovered after my landing at Kobe, were aimed in a big way, and most devilish, at my purse. . . . The story is an amazing one, particularly the part played by dealers, long enough for a sensational novel, unholy enough to satisfy a missionaries’ dream and beset with the greatest aesthetic pitfalls I have thus far met. The closing act, I dare not put on paper.” Lawton and Merrill report that the “closing act” was Freer forcibly removing a fake Buddhist priest from his hotel room.[8]

History in Light of Cultural Influences

It is possible that Loo was simply acting within the tradition of Chinese antique dealers. He was, after all, born and raised in China. A contemporary Chinese museum director related this scenario to me regarding his knowledge and experience with Chinese antique dealers and explaining what he called “unwritten rules”: “Let’s say that an antique dealer bought a plate from someone for RMB 30 [Renminbi, the official currency of China], and one day a customer wants to buy this plate from him, then it’s very likely that the antique dealer will ask for RMB 15000, and even pretends like he offers the lowest price, saying he just bought it from someone else for RMB 13000. . . . [T]he point is that both the buyer and seller know that the seller is not telling the truth, it’s just a tactic for bargaining.”[9]

Agnes E. Meyer, Freer’s friend and colleague when buying Chinese art, confirms that this was also the attitude of the 1910s.[10] It seems almost certain this was Loo’s modus operandi when he dealt with Freer.

History from a Psychological Perspective

Charles Freer reacted to Loo’s unacceptable behavior over and over again and he eventually made it clear he no longer wished to deal with Loo, who had tried Freer’s good graces once too often. This was similar to what later transpired between Loo and Eli Lilly. Offers are rejected not only on the basis of monetary considerations, but also as a form of punishment for an unfair action on the part of the seller. Moreover, a rejection, according to studies by Ernst Fehr and Urs Fischbacher, can promote more reasonable and accommodating behavior in the future.[11] Unfortunately, this was not the case with Loo, as evidenced by his dealings with Lilly decades later.

There is also recent research that suggests unfair or unreasonable offers can generate anger toward the perpetrator, in this case the buyer toward the seller.[12] Freer clearly did not want to deal with Loo again. Lilly, who lived in Indianapolis, wrote to Loo, “Don’t come to Indianapolis.” Both men distanced themselves from the seller, and in both situations it is possible, even likely, that anger fueled their aversion not only to the deal but to the dealer as well. Feelings of disgust for the seller can also arise, as it is an avoidance reaction originally developed to protect an individual from a harmful contaminant such as worm-infested food. In modern society, disgust is also associated with moral codes relating to social misbehaviors, such as lying or misrepresentation.[13] This revulsion leads to avoidance of social interaction with those not in line with the norm in the opinion of the person in judgment.

A critic of the conjectured neuropsychological insights above might say that Freer was old and ill and that these factors might have contributed to his lack of patience with Loo. Evidence suggests that was not the case. His close friend Agnes Meyer wrote that although Freer was fragile and had become increasingly sensitive to whatever bothered him in 1917, he did not “become mentally affected” until 1918–1919, well after he had severed ties with Loo.[14]

Conclusion

Loo’s preconceived ideas about how to sell his wares in America were surely shaped by his cultural experiences, but even after his client Charles Lang Freer attempted to teach him a better business model, Loo’s unscrupulous conduct was in evidence thirty years later in his dealings with Eli Lilly, and presumably existed at many or all points in between. The consequence of his behavior was that Freer and Lilly both reacted based on human characteristics that we now recognize through neuropsychological studies, and each sought to distance himself from Loo. This of course affected Loo’s business at the time, but his failure to adopt the kind of professionalism Freer tried to impart to him has also tainted his legacy as the premier dealer of Asian art in America in the first half of the twentieth century.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I wish to thank David Hogge, Head of Archives at the Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., for his generous and valuable help with resources.

Shirley M. Mueller, “Eli Lilly Jr. (1885–1977): How New Science and Historic Archives Reveal a Collector’s Decision-Making Process,” Collections: A Journal for Museum and Achieves Professionals 7, no. 3 (2011): 289–98; Mueller, “Tug of War: Mr. Lilly Collects,” Traces (Summer 2013): 18–25; Mueller, “Eli Lily [sic] Collects: Emotions at Work,” Fine Art Connoisseur (July/August 2011): 49–50.

James J. Lally, Pope Memorial Lecture, “Two Great American Collectors of Chinese Ceramics: Morgan and Freer,” at The Freer Gallery of Art and The Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., June 25, 2011; available online at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CijiYxZh1qQ (uploaded August 8, 2011).

Yiyou Wang, “The Loouvre from China: A Critical Study of C.T. Loo and the Framing of Chinese Art in the United States, 1915–1950,” Ph.D. diss., Ohio University, 2007.

Ingrid Larsen, “‘Don’t Send Ming or Later Pictures’: Charles Lang Freer and the First Major Collection of Chinese Painting in an American Museum,” Ars Orientalis 40 (2011): 6–38.

Thomas Lawton and Linda Merrill, Freer: A Legacy of Art (Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, in association with Harry N. Abrams, 1993), p. 59; Larsen, “Don’t Send Ming or Later Pictures,” p. 22.

Unless otherwise noted, all quotes from correspondence between Charles Lang Freer and C. T. Loo are taken from letters exchanged between March 16 and December 16, 1916, in the Charles Lang Freer Papers, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., Gift of the Estate of Charles Lang Freer

Lawton and Merrill, Freer: A Legacy of Art, p. 73.

Ibid.

Email communication between the author and Chunming Yu, director of the Nanchang University Museum in Nanchang, China, November 23, 2012, based on his interpretation of conversations with old antique dealers in China and as characterized in the Chinese television series “Sophora Flower of May.”

Agnes E. Meyer, Charles Lang Freer and His Gallery (Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art, 1970), p. 16.

Ernst Fehr and Urs Fischbacher, “The Nature of Human Altruism,” Nature 425 (October 23, 2003): 785–91. For recent neuropsychological studies on this topic, see, e.g., Shirley M. Mueller, “The Neuropsychology of the Collector,” in Steven Satchell, ed., Collectible Investments for the High Net Worth Investor (Oxford: Academic Press, 2009), pp. 31–51; Mueller, “Why Collectors Collect,” Fine Arts Connoisseur (January/February 2010): 59–61; and Mueller, “Inside a Collector’s Head,” Aziatische Kunst 42, no. 4 (December 2012): 2–12.

Madan M. Pillutla and J. Keith Murnighan, “Unfairness, Anger, and Spite: Emotional Rejections of Ultimatum Offers,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 68, no. 3 (December 1996): 208–24.

. Joshua M. Tybur, Debra Lieberman, and Vladas Griskevicius, “Microbes, Mating, and Morality: Individual Differences in Three Functional Domains of Disgust,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 97, no. 1 (July 2009): 103–22.

Meyer, “Charles Lang Freer and His Gallery,” p. 19.