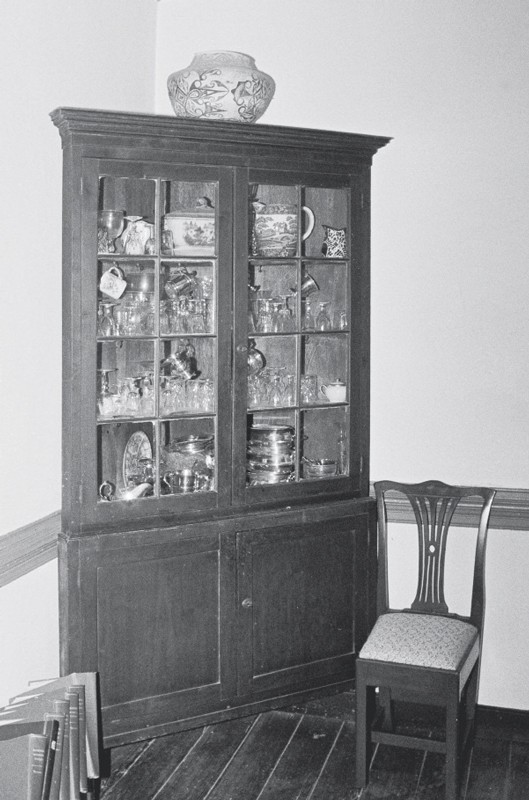

Zuni water jar, 1880–1895, in the St. George Tucker House dining room, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1986. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Willie Graham.)

Randy Nahohai, 2011. (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Decorating Pottery, engraving by H. F. Farny, published in Frank Hamilton Cushing, “My Adventures in Zuñi,” Century Magazine 25, no. 2 (December 1882): 201. (Courtesy, Cornell University.)

Pueblo of Zuni, 1879. (Photo, John K. Hillers; courtesy, Cowan’s Auctions.) Hillers accompanied James and Matilda Stevenson and Frank Hamilton Cushing to Zuni.)

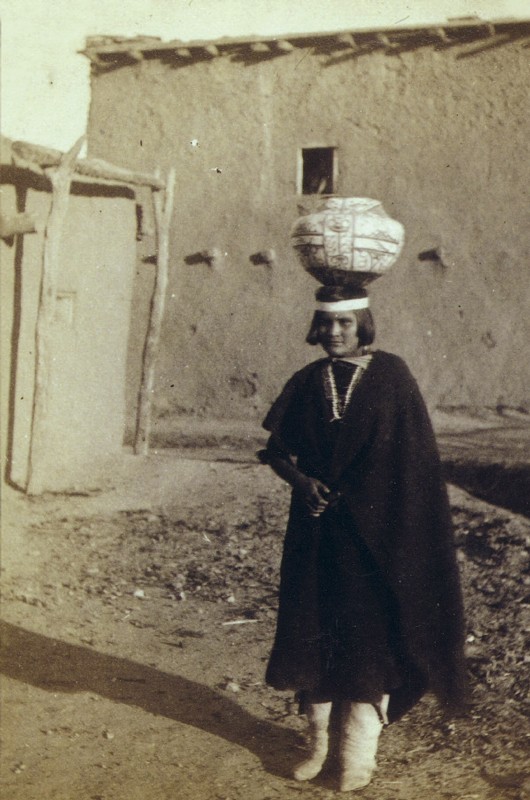

Young Zuni woman with water jar, 1873. (Photo, Corps of Engineers, attributed to Timothy O’Sullivan; author’s collection.)

Bottomless jars used in constructing chimneys, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1879. (Photo, John K. Hillers; courtesy, Cowan’s Auctions.)

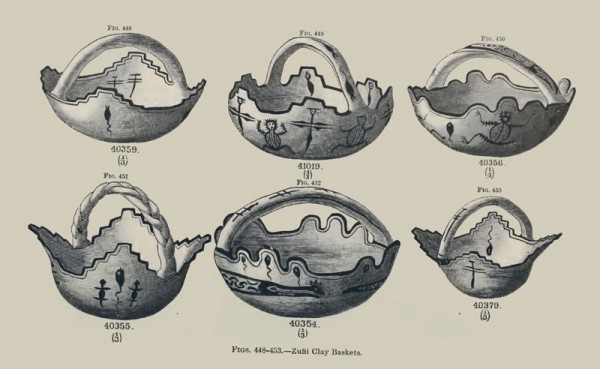

Terraced bowls collected by James Stevenson at Zuni in 1879, published by Bureau of Ethnology, Annual Report, 1883, figs. 448–53. (Courtesy, Smithsonian Institution.)

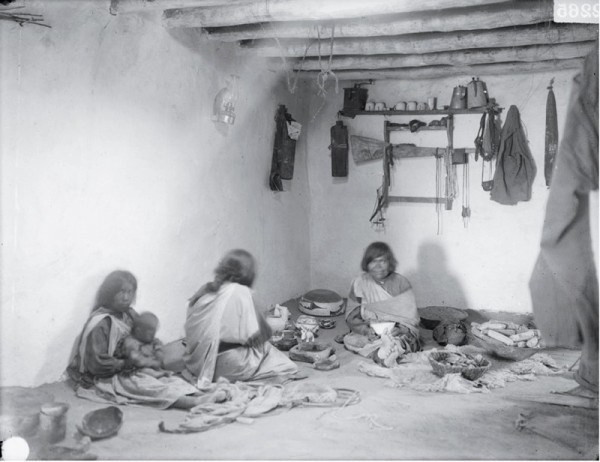

Zuni house interior with plain walls, masonry benches, and water jars, 1899. (Courtesy, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution; photo, Adam Clark Vroman, NAA. GN02297.)

Zuni house interior with women burnishing and painting pottery, 1899. (Courtesy, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution; photo, Adam Clark Vroman, NAA. GN02265.)

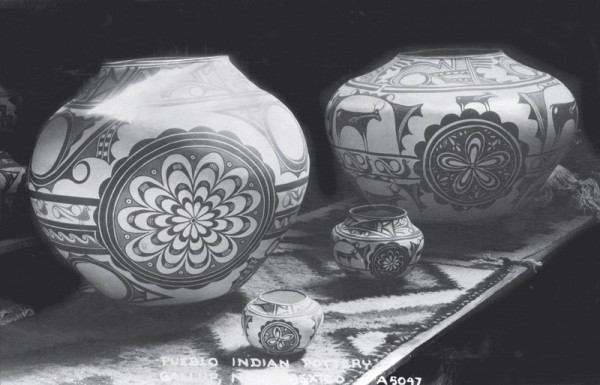

Zuni vessels assembled for the tourist trade, ca. 1900. (Photo, author’s collection.)

Photograph showing aestheticization of Zuni vessels, in sharp contrast to the earlier view in fig. 10. (Photo, Burton Frasher; author’s collection.) The jars are probably by Tsayutitsa, ca. 1930.

Sikyatki Revival bowl with avian motif, Daisy Hooee Nampeyo, Hopi-Tewa, 1950–1970. Earthenware. D. 8 1/4". (Photo courtesy, Quinn's Auction.) In shape, color, and motifs, this vessel is quite unlike those she taught Zuni students to make.

Jar, Eudora Montoya, Santa Ana Pueblo, New Mexico, 1960–1970. Earthenware. H. 7". (Unless otherwise noted, all objects in author’s collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jars, John Montoya, Sandia Pueblo, New Mexico, 1994. Earthenware. H. of tallest 3 1/2", H. of shortest 1 7/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jars, Kewa Pueblo, New Mexico. Earthenware. Left: Andrew William Pacheco, 1990. H. 4 3/4". Center: Robert Tenorio, ca. 1988–1989. H. 5 7/8". Right: Andrew William Pacheco, 1991. H. 5 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Objects by Diego Romero and Santiago Romero, Cochiti Pueblo, New Mexico. Earthenware. Left: Bowl, Diego Romero, 2006. D. 8 1/2". Inscribed “American Highway: Still Truckin’.” Center: “Desert Lylee” (Romero family dog), Santiago Romero, 2012. H. 10 5/8". Unmarked. Right: Bowl, Diego Romero, ca. 2008. D. 7". Inscribed “On the Green” (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Lizard jar, Teresita Romero, Cochiti Pueblo, New Mexico, 1950–1975. Earthenware. H. 6". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar, Tsayutitsa, owned by Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1939. Earthenware. H. 21 5/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Indian Arts and Culture.)

Zuni women with water jars, ca. 1931. (Photo, Burton Frasher; author’s collection.)

Zuni pottery owls, New Mexico, ca. 1950–2015. Earthenware. Back row: Unidetsa Kallestewa, Erma Kalestewa Homer, and Myra Eracho; middle row: Spotted-Feather Owl Potter, Bica-Kalestewa family, Eileen Yatsattie, Quanita Kalestewa, and Zoe Jarmon (two); front row: Spotted-Feather Owl Potter (two), Josephine Nahohai, Erma Homer, Nellie Bica, Nellie Bica and Erma Homer, Rowena Kalestewa, Erma Homer, Celecita Vicente, and Sadie Tsipa. H. of tallest 11", H. of shortest 2 3/8". (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

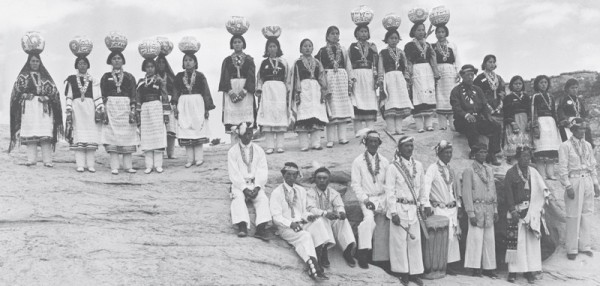

Lawsaiyatesetsa (far left, back row) at Gallup Inter-Tribal Ceremonial, 1937. (Photo, H. Eisenhand; author’s collection.) She carries a jar different from the Deer in His House and Rainbird jars carried by the younger women.

Lawsaiyatesetsa (far left) at Gallup Inter-Tribal Ceremonial, 1938. (Photo, Burton Frasher; author’s collection.)

Jars, Tsaw-a:si, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1951. Earthenware. H. 6 1/2", 9 1/4". (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Offering bowls by (left to right) Erma Kalestewa Homer, Eileen Yatsattie, and Brandon Kallestewa, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, ca. 1995, ca. 2000, 2004. Earthenware. D. 7 1/4", 8”, 6 7/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The bowl on the far right is slipcast.

Erma Kalestewa Homer holding a stew bowl made by her grandmother Nellie Bica in about 1980. (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Pitcher for Rain Priests, Rowena Him, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, ca. 1987. Earthenware. H. approx. 11". (Photo, courtesy Milford and Randy Nahohai.)

Bowls for Rain Priests, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, (left to right) 1986–1990, 1945–1960, 1980–1985. Earthenware. W. (left to right) 12", 9 3/8", 11 3/4". (Courtesy, Eileen Yatsattie; photo, Edward Chappell.) The bowls on the right and left are Eileen Yatsattie’s first and second replacements for the center bowl, by Margaret Walela.

Left and right: Jars, Jack Kalestewa, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1985–1990. Earthenware. H. 5 1/4", 6 1/2". Center: Cornmeal bowl, Quanita Kalestewa, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1985–1990. Earthenware. W. 10". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar decorated with Deer in His House motif, Nellie Bica, painted by Erma Kalestewa Homer, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, ca. 1985. Earthenware. H. 9 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

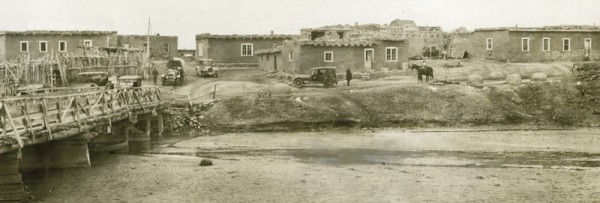

Zuni River and town viewed from the south, ca. 1920, when Josephine Nahohai was a young girl. (Photo, author’s collection.)

Plate with He-lele Ko’hanna figure painted by Dixon Shebala after industrial firing, 1962. Stoneware. D. 10 1/4". Signed on obverse: “Shebala – 62"; mark on reverse: “BAUER CALIF-U.S.A.” (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

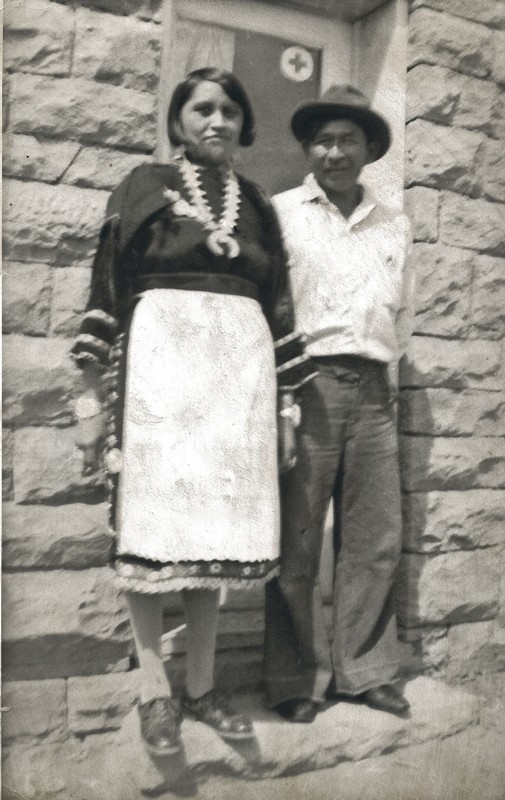

Josephine and Nat Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, ca. 1945. (Photo, courtesy of Milford and Randy Nahohai.)

Jar, Myra Eriacho, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1950–1960. Earthenware. H. 4 3/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar, Ethel Youvella, Tewa-Hopi, Polacca, Arizona, 1975–1990. Earthenware. D. 10 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Zuni potter Kyusita, also called Cayusetsa, applying coils of clay, 1918. (Photo, George H. Pepper; author’s collection.)

Unfired jar, Quanita Kalestewa, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1987. Earthenware, painted with hematite brown and yellow ochre over kaolin slip. D. 6 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Kyusita, having stacked dried dung over unfired pottery, 1918. (Photo, George H. Pepper; author’s collection.)

Zuni woman firing pottery, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1932. (Photo, Burton Frasher; author’s collection.)

Owl, Josephine Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, ca. 1960. Earthenware. H. 9 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar, Josephine Nahohai, painted by Nat Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, ca. 1965–1975. Earthenware. H. 4 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jars, Josephine Nahohai, painted by Nat Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1975–1982. Earthenware. H. (left to right) 4 1/4", 9 1/2", 7". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The two smaller jars have white slip; the larger one is unslipped.

Josephine Nahohai (second from left) performing with Olla Maidens at Heard Museum, Phoenix, 1982. (Photo, courtesy Billie Jane Baguley Library and Archives, Heard Museum, call number PCD:199B 1276589_0042.) Josephine is balancing a slipcast jar painted by Randy Nahohai.

Owl by Jaycee Nahohai that broke during outside firing, 2010. (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Frog bowls (left and center), Josephine Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1970–1984. Earthenware. W. 6 3/8", 6 3/4". Turtle bowl (right), Josephine and Milford Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1986. Earthenware. W. 6 3/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

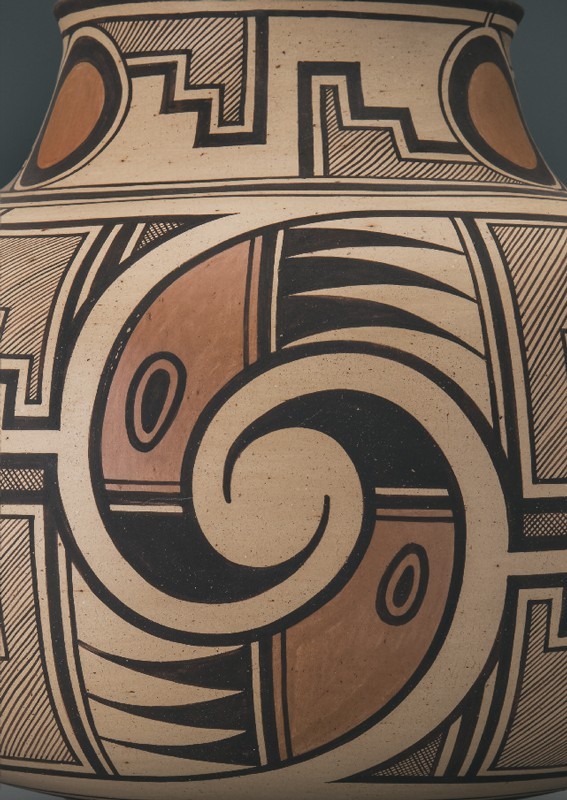

Jar, Josephine and Milford Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1986. Earthenware. H. 9". (Courtesy, the School for Advanced Research, SAR.1986-16-1; photo, Addison Doty.)

Cornmeal bowls by Josephine Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1975–1985. Earthenware. Left: Painted by Josephine Nahohai. W. 6". Center: Painted by Nat Nahohai. W. 6 3/8". Right: Painted by Randy Nahohai, who regularized Josephine’s terraces by applying a black border and ornamented the bowl with tadpoles and dragonflies. W. 6". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar, Josephine Nahohai, painted by Randy Nahohai with Deer in His House motifs, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1978–1984. Earthenware. H. 9 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side view of the jar illustrated in fig. 47, showing dagger motifs flanking doubled and quadrupled frets. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar, Josephine and Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1985. Earthenware. H. 8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar, Josephine, Randy, and Milford Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1983. Earthenware. H. 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Heard Museum Collection, object number NA-SW-ZU-A7-44; photo, Craig Smith.)

Randy Nahohai with stew bowl made for his mother as part of a set for Cindy Tsethlikai’s Shalako house ceremony, 1978. W. 14 1/4". (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Corn figure, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1984. Earthenware. H. 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of the American Indian.)

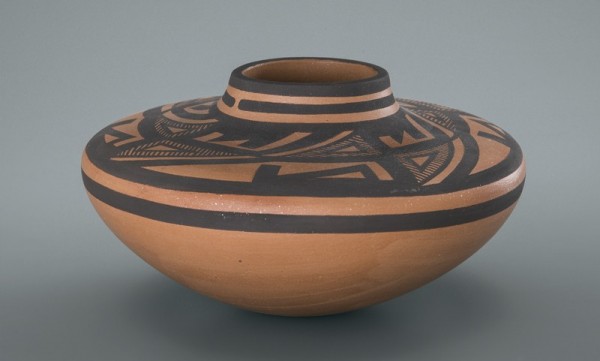

Seed jars, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1984. Earthenware. H. of larger jar approx. 5". (Photo, courtesy Randy Nahohai.)

Vera Eustice in costume carrying a jar decorated with pairs of capped spirals, daggers, and circles, ca. 1940. (Photo, Burton Frasher; author’s collection.)

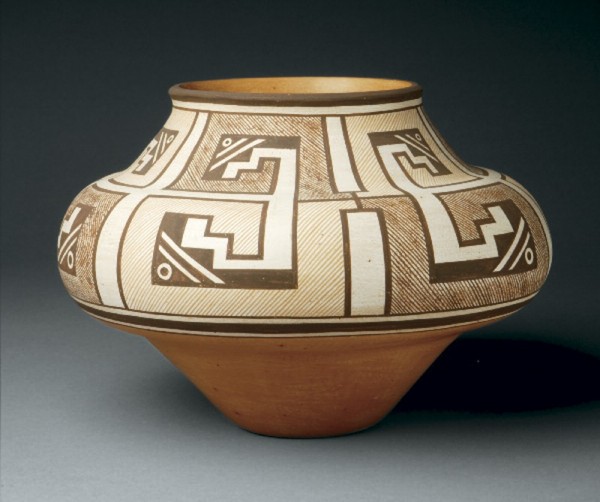

Jar, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1985. Earthenware. H. 5 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

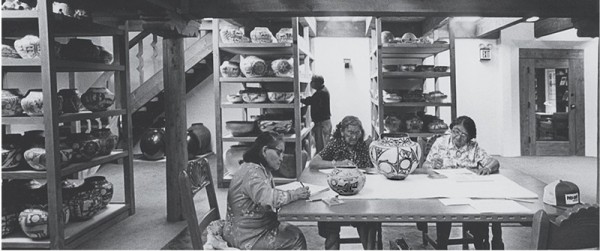

Rose Gasper, Josephine Nahohai and Eloise Westika sketching designs from Zuni pottery at the School of American (now Advanced) Research, Santa Fe, New Mexico. (Photo, Stephen Trimble.)

Jar, Eloise Westika, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1980–1990. Earthenware. H. 4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jars, decorated with Bird in Its House designs, Josephine and Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, ca. 1985 (left), 1986 (right). Earthenware. H. 9", 7 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

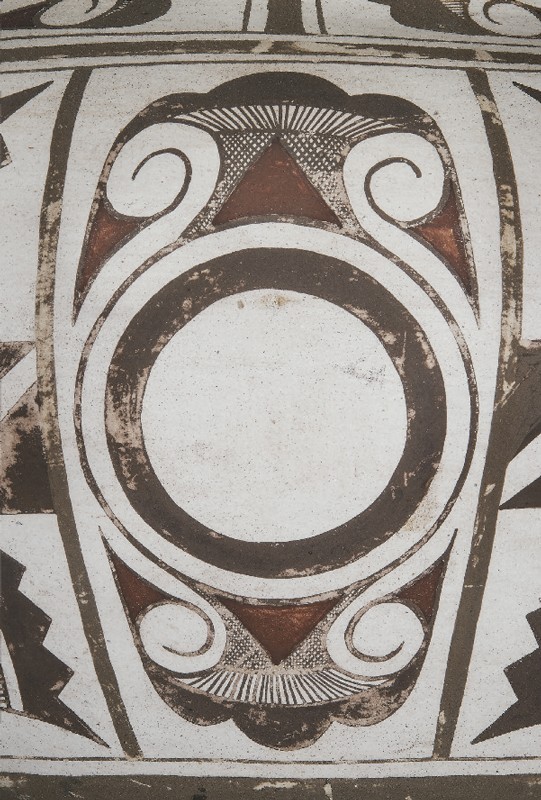

Spacer panel with crooked circle motif on the ca. 1985 jar illustrated on the left in fig. 58, painted by Randy Nahohai. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Rainbird jar, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1985. Earthenware. Dimensions unknown. (Photo, courtesy Milford Nahohai.)

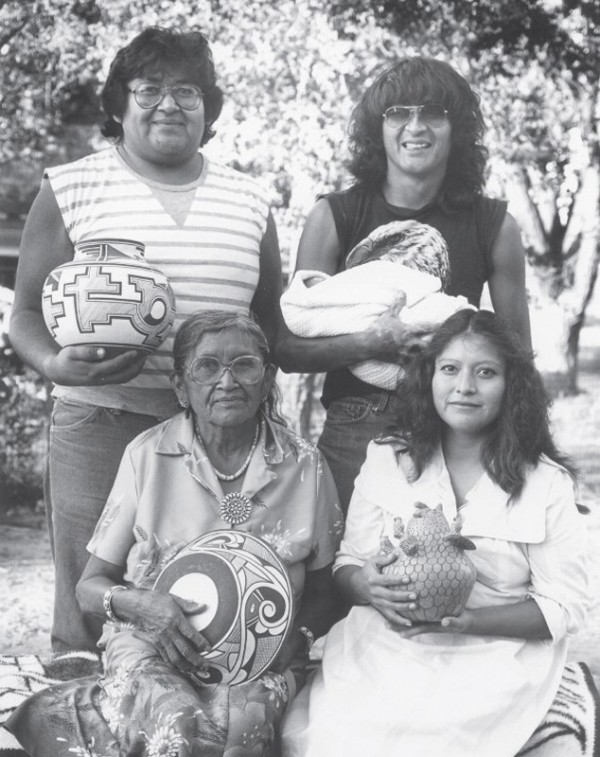

Nahohai family (clockwise from upper left): Milford with Randy’s 1985 Rainbird jar, Randy holding newborn Jaycee, Rowena Him with a pottery owl by Josephine, and Josephine with a Rainbird bowl by Randy. (Photo, Steven Trimble.)

Fragmentary Kiapkwa Polychrome dough bowl from Zuni, ca. 1830. Earthenware. W. 17". (Courtesy, Museum of Indian Arts and Culture.)

Jar, Josephine Nahohai, painted by Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1986. Earthenware. H. 9 7/8". Catalogue No. 87.48.20 (Courtesy, Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, University of New Mexico.)

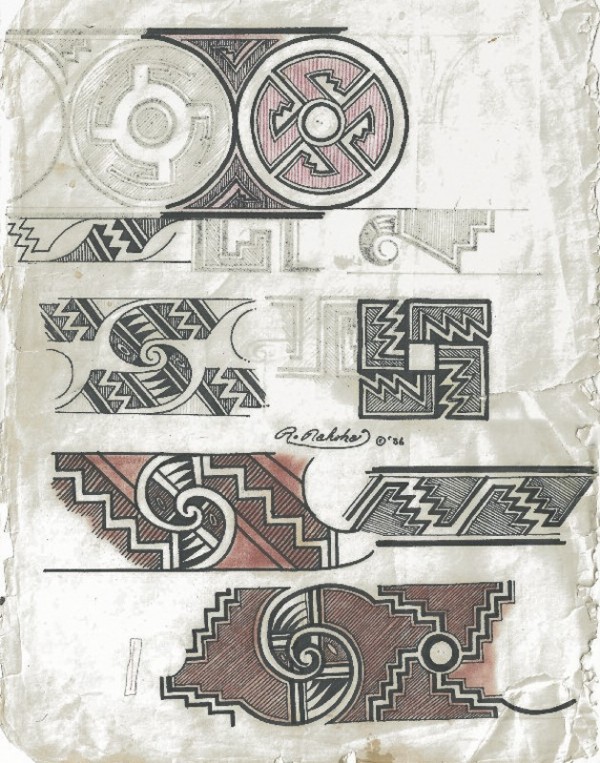

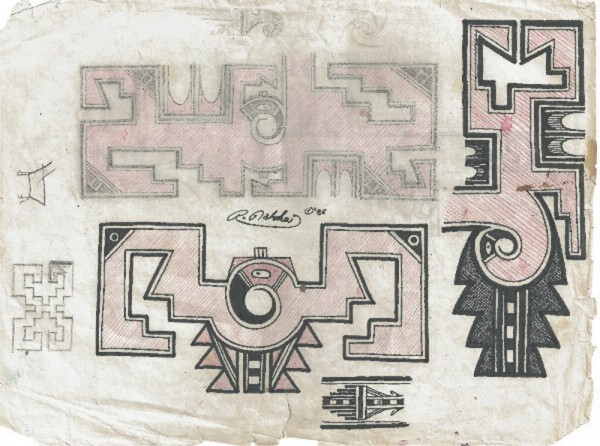

Sketches for directional figures and Rainbirds, Randy Nahohai, 1986. Graphite, ink, and colored pencil on paper. 10 3/4" x 14". (Courtesy, Randy Nahohai.)

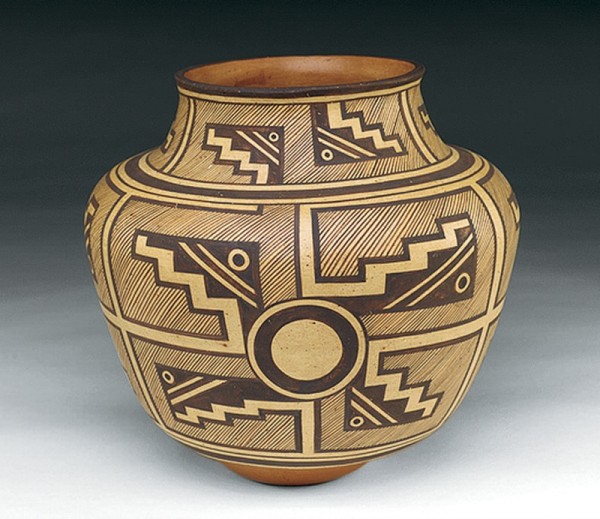

65 Jar, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1988. Earthenware. H. 14 1/2". (Courtesy, Milford Nahohai; photo, Edward Chappell.)

Jar, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1998. Earthenware. H. 10 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1997. Earthenware. H. 8 7/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1998. Earthenware. D. 10 1/2". (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Jar, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1988. Earthenware. H. 8 5/8". (Photo, National Museum of the American Indian.)

Jar, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1987. Earthenware. H. 10". (Courtesy, Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art, Indianapolis.)

Jar, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1987. Earthenware. H. 7 7/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1987. Earthenware. H. 12 1/2". (Photo, Bonhams.)

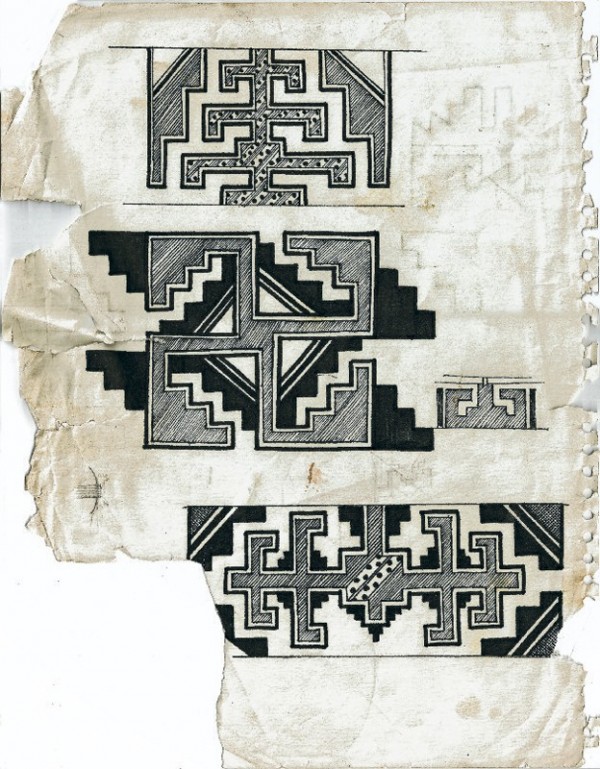

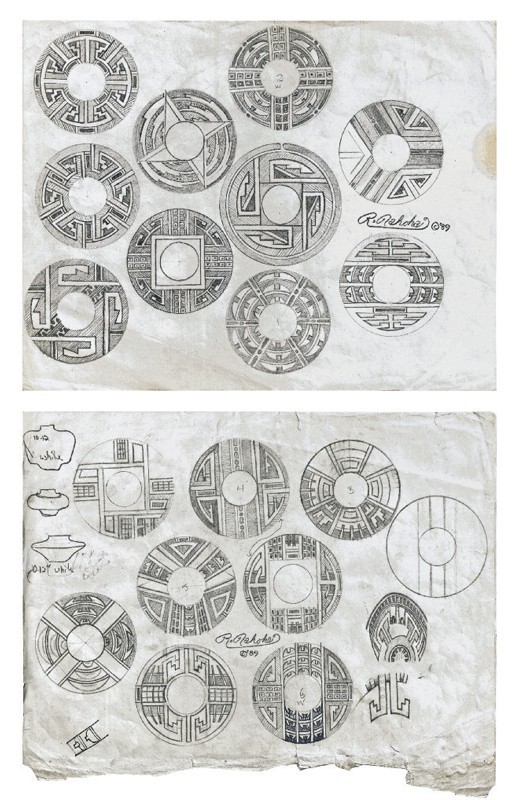

Sketches for geometric and directional figures, Randy Nahohai, ca. 1986. Graphite and ink on paper. 10 3/4" x 14 1/8". (Courtesy, Randy Nahohai.)

Sketches for Rainbird evolution, Randy Nahohai, 1986. Graphite, ink, and red pencil on paper. 10 3/4" x 14". (Courtesy, Randy Nahohai.)

Rainbird jar, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1985. H. 9". (Courtesy, Treadway Gallery.)

Rainbird motif, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1987. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jars, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1987. Earthenware. H. 12 1/2" (left), 9 5/8" (right). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1988. Earthenware. H. 12 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar decorated with hanging cloud motifs, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1988. Earthenware. H. 14". (Courtesy, John Barry.)

Jar, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1987. Earthenware. H. 10 3/4". (Courtesy, Heard Museum, object number 4070-1; photo, courtesy Milford Nahohai.)

Corrugated pottery sherd from surface at Hawikuh village, precontact. (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Jars, two with corrugated necks, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1987–1988. Earthenware. (Courtesy, Randy Nahohai; photo, Randy Nahohai.)

Hawikuh Polychrome jar fragment, glaze-painted, 1630–1680. (Courtesy, Milford and Randy Nahohai; photo, Edward Chappell.)

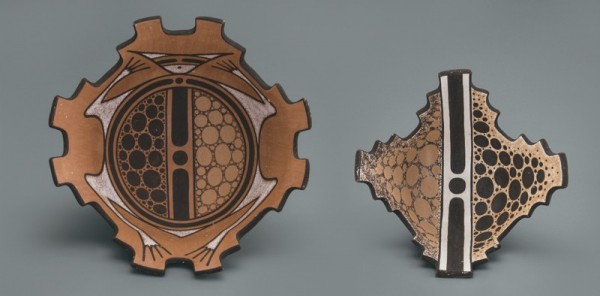

Jar, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1988. Earthenware. D. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, the School for Advanced Research, SAR.1994-4-600; photo, Addison Doty.)

Bowl made for Brenda Shears, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1987. Earthenware. D. 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Keith Kintigh and Brenda Shears; photo, Brenda Shears.)

Hawikuh flying saucer jar, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1989. Earthenware. D. 14 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar (top) and bowl (bottom) with Rainbird compositions, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1990 (jar), 1991 (bowl). Earthenware. D. 11 1/2", 12 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Two sheets of designs for painting jars, Randy Nahohai, 1989, inspired primarily by William Baake’s drawings of pottery excavated at Hawikuh. Graphite on paper. 14" x 11". The rough sketch for a flying saucer jar viewed from the side is labeled “10–12 white for Brenda Shears” on the left. (Courtesy, Randy Nahohai.)

Jars, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1989. Earthenware. D. 8 1/8" (left), 5 7/8" (right). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

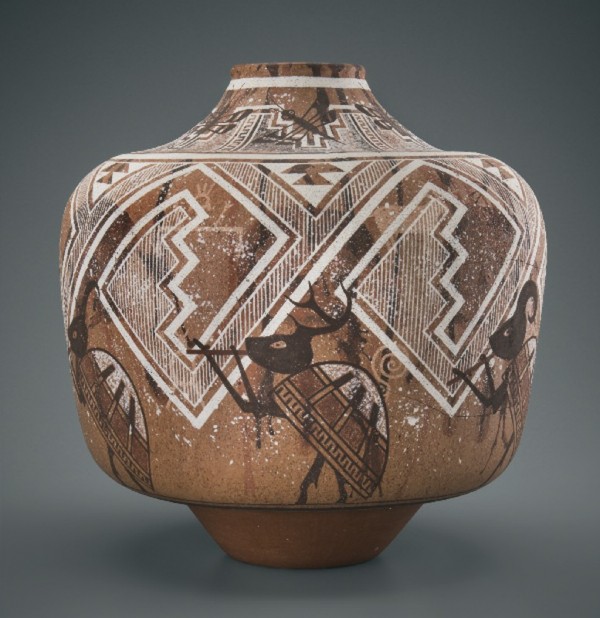

Jar decorated with designs drawn from Matsaki Polychrome vessels, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1989. Earthenware. D. 13 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

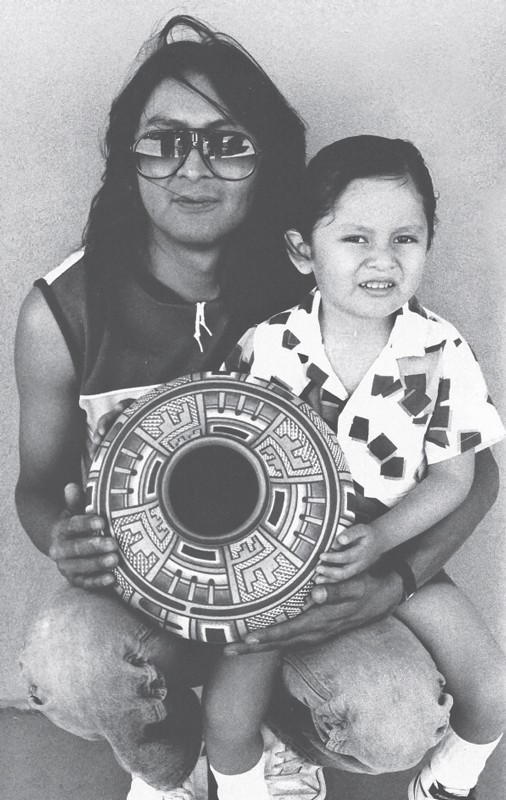

Randy and Jaycee Nahohai with jar, 1989. (Photo, James Ostler, courtesy Milford and Randy Nahohai.)

Bowl decorated with Antelope motif, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1992. Earthenware. D. 8 1/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bowl decorated with Flute Player motif, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1992. Earthenware. D. 9". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bowls with flared rims and corrugated coils, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1992 (left), 1991 (right). Earthenware. Left: white-slipped exterior with rose-painted coil. D. 8 1/8". Right: orange-slipped exterior with unburnished coil. D. 12 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bowl decorated with Wood Rat motif, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1992. Earthenware. D. 8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bowl, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1990. Earthenware. D. 7 5/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bowl decorated with design inspired by a 1350–1450 Gila Polychrome jar, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1992. Earthenware, with unslipped surface. D. 7 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bowl decorated with Knifewing motif, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2009. Earthenware. D. 8 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bowl decorated with Longhair motif, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico. Earthenware. D. 7 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bowl, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2009. Earthenware. D. 7 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bowl, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2009. Earthenware. D. 7 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Kaleidoscope jars, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2007. Earthenware. H. 7 5/8" (left), 8" (right). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Flute player rock art, Village of the Great Kivas, Zuni, precontact. (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Cornmeal bowl decorated with flute players and frogs, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1988. Earthenware. W. 8 3/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar, Randy Nahohai, 1990. Earthenware. H. 12 1/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Indian Arts and Culture.)

106 Jar, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1991. Earthenware. H. 14". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The stains running down the face of the jar and the inverted brown handprints (as at the center) are applied before the figures and multiple white cloud motifs.

Detail of the cliff-faced belly on the jar illustrated in fig. 106, showing petroglyph, Hanging Cloud motif, and flute player. (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Jar, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1991. Earthenware. D. 14". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This view of the top shows six painted terraces, cloud motifs, and dragonflies.

Rainbird sketches, Randy Nahohai, 1985. Graphite, ink, and colored pencil on paper. 14" x 10 3/4". (Courtesy, Randy Nahohai.) Randy drew the more conventional Rainbird patterns at upper left before painting the 1985 jar illustrated in fig. 60.

Rainbird jars, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1999 (left), 2007 (right). Earthenware. H. 8 1/2", 7 3/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jars decorated with deer, antelope, and rams, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2006 (left), 1996 (center), 2010 (right). Earthenware. H. 6 7/8", 6 5/8", 6 3/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Micaceous orange slip is hand-rubbed inside the lip of all three and on the outside of the jar on the far right. Flute players are painted on the lower body of the middle jar.

Jars decorated with Deer in His House motifs, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1999 (left and center), 2002 (right). Earthenware. H. 7 3/8", 7 5/8", 7 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Micaceous orange slip is hand-rubbed inside the lips and some mica is included in the unsmoothed brown.

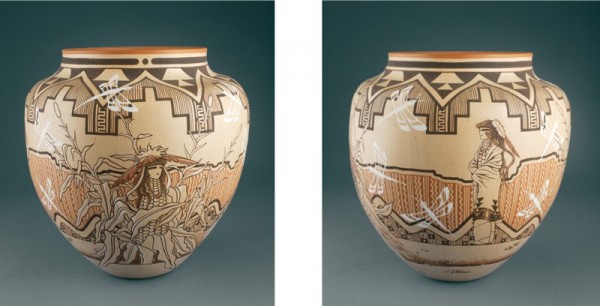

Jar decorated with Corn Maiden scenes, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1994. Earthenware. H. 12 1/8". (Courtesy, Denver Art Museum.)

Cornmeal bowl, Rowena Him, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1987. Earthenware. H. 4 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Cornmeal bowls decorated with frog (left) and frogless (right) pattern, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1992. Earthenware. W. 10 1/2", 8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Cornmeal bowls decorated with frog figures, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2009 (top), 2011 (bottom). Earthenware. W. 6 1/2", 6 3/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Frog and lizard flutes, 2004 (left), 2007 (center), 2011 (right). Earthenware. L. 7", 3 1/2", 7". (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Frog jars, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2002 (left), 2006 (center), 2009 (right). Earthenware. H. 5 1/2", 6 1/2", 5 7/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Micaceous orange slip covers the outside and extends inside the lip.

Jar, “Frog on Maize,” Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2008. Earthenware. H. 6 1/4", D. 7 1/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Top view of the jar illustrated in fig. 119. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jars decorated with cloud patterns, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1999 (left), 2012 (center), 2009 (right). Earthenware. H. 5", D. 8 1/4", H. 5". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tularosa Star, the center jar illustrated in fig. 121. H. 7 7/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Top view of the center jar illustrated in fig. 121, showing penciled guidelines. (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Dragonfly motif on a potsherd from the surface at the Hawikuh site, seventeenth century. (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Cornmeal bowls with Milky Way decoration, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2002 (top) and 2009 (bottom). Earthenware. W. 7 1/8" and 8 3/4". (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Cornmeal bowl, Josephine Nahohai, painted by her grandson Dion Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1989–1992. Earthenware. W. 6 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Cornmeal bowls, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2002 (left), 2013 (center), 2009 (right). Earthenware. D. 7 1/8", 8 3/4", 6 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2008. Earthenware. H. 5 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bowls with sun spirals, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1999 (top), 2006 (middle), 2007 (bottom). Earthenware. D. 4 1/4", W. 9 3/8", W. 10 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jars with Kolowisi, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2006 (left), 2008 (right). Earthenware. H. 7 1/2", 9 1/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bowl, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2007. Earthenware. D. 10 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar and bowl, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2011 (left), 2013 (right). Earthenware. H. 8", W. 7 1/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

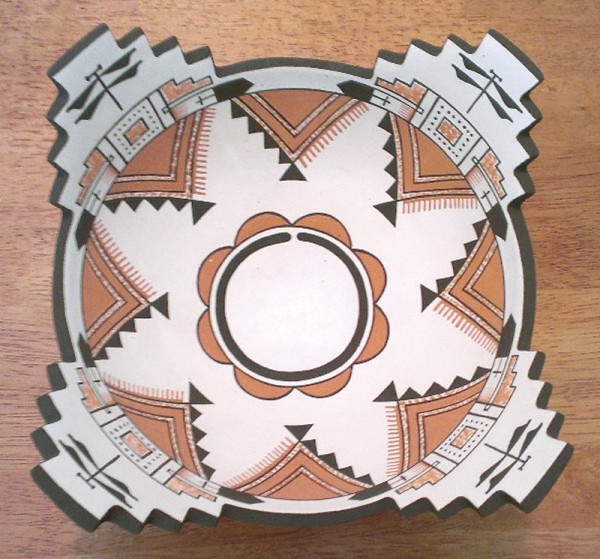

Bowl, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2014. Earthenware. W. 10". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jars decorated with motifs drawn from rock art figures, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, (left to right) 2004, 2007, 2011, 2011. Earthenware. H. 6 3/4", 6 7/8", 7", 8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Cornmeal bowl decorated with rock art motifs, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2014. Earthenware. W. 12". (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Cornmeal bowl made for Darrell and Shaun Tsabetsaye, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2012. Earthenware. W. approx. 12". (Photo, Shaun Tsabetsaye.)

Medicine bowl, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2012. Earthenware. W. 12". (Photo, Shaun Tsabetsaye.)

Cornmeal bowls, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2012 (top), 2013 (bottom). Earthenware. W. 11 3/8", 8 3/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Cornmeal bowl decorated with motifs of Pinnawa Glaze-on-white bowls from 1350–1450, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2013. Earthenware. D. 9 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Cornmeal bowl, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2013. Earthenware. W. 8 3/8". (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Cornmeal bowl, Prayers and Messengers, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2015. Earthenware. D. 9 3/4". (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Jar, Anderson Peynetsa, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1989. Earthenware. H. 5 3/8". (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Jar, Alan E. Lasilou, New Mexico, ca. 2007. Earthenware. H. 5 7/8". (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Jar with painted and decal decoration, Les Namingha, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 2010–2011. Earthenware. H. 5". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth)

Jar, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2013. Earthenware. H. 8 3/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Duck vessel, Rowena Him, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1998. Earthenware. L. 7 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Frog vessel, Rowena Him, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1996. Earthenware. L. 6". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pottery bears, Rowena Him, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1988–1992. Earthenware. L. 2 3/4" (left), 2 3/8" (right). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Canteens, Rowena Him, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1993 (top), 1998 (bottom). Earthenware. H. 7 1/4", 6 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bowl, Rowena Him, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2005. Earthenware. D. 6 1/4". (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Jar, Rowena Him, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2008. Earthenware. D. 7 7/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar, Josephine and Milford Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, ca. 1990. Earthenware. D. 4 7/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Cornmeal bowl, Josephine and Milford Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1994. Earthenware. D. 7 7/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Owls, Josephine and Milford Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1998 (left), 2000 (center), 2001 (right). Earthenware. H. 6 1/8", 6 1/2", 6 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Cornmeal bowl and incense burner, Milford Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2002 (corn bowl) and 2010 (incense burner). Earthenware. W. 5 7/8", D. 6", respectively. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Milford Nahohai, at Village of the Great Kivas, 2011, who is particularly interested in spirals with pairs of outer scrolls, as seen at upper left. (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Parrot bowls. Rowena Him, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1995 (top), 2000 (second). Earthenware. D. 5 1/2", 7". Milford Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2004 (third), 2010 (bottom). Earthenware. D. 6 3/8", 6 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Kechipawan parrot bowl, Milford Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2012. Earthenware. D. 6 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of incense burner with colored frogs illustrated in fig. 155, Milford Nahohai, 2010. (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Jar, Milford and Jaycee Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2013–2014. Earthenware. D. 7 1/2". (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Cornmeal bowl, Eileen Yatsattie, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, June 1997. Earthenware. W. 5 7/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Eileen Yatsattie with her traditionally made second bowl for Rain Priests. (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Owls, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 1989. Earthenware. Left: Shaped and painted by Irma Nahohai. H. 6 1/2". Back center: Shaped by Josephine Nahohai and painted by herself and Irma. H. 7 7/8". Right: Shaped by Josephine and painted by Maynard Nahohai. H. 7 3/8". Chicken figure (front center) by Josephine and painted by Maynard, ca. 1990. W. 4 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Cornmeal bowls and jars, Josephine Nahohai, painted by Maynard Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, ca. 1990. Earthenware. H. of large jar 6 1/4", W. of small bowl 3 7/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Maynard Nahohai with his painted and sgraffito-decorated greenware stew bowl for Long Horn House, 2008. (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Jaycee Nahohai with his first large owl, 2012. (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Small bowls, Jaycee Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2004 (bottom left), 2009 (top), 2010 (bottom right). Earthenware. D. 5 1/4", 5 1/4", 4 7/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar, Randy and Jaycee Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2007. Earthenware. H. 5 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Puzzle jar, Jaycee Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2013. Earthenware. H. 7 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pitchers, Jaycee Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2014. Earthenware. D. 8 5/8" (left), 7 5/8" (right). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Kolowisi plate, Jaycee Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2011. Earthenware. D. 10 5/8". (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Frog jars, Jaycee Nahohai, (right) shaped by Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2012. Earthenware. H. 6", 7 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Owls, Jaycee Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2009 (left), 2010 (center), 2011 (right). Earthenware. H. 5 1/2", 4 7/8", 5 3/4". (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Owls, Jaycee Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2013 (left) and 2014 (right). Earthenware. H. 7 1/8", 7 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

First large owl to survive, Jaycee Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2013. Earthenware. H. 15 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jaycee Nahohai shaping a jar lid on a banding wheel, 2015. (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Lidded jar, Jaycee Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2014. Earthenware. H. 9 7/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Storyteller owl, Jaycee Nahohai and Rowena Him, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2014. Earthenware. H. 7". (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Lidded jar, Jaycee Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2014. Earthenware. D. 12". (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Lidded jar, shaped by Rowena Him and Jaycee Nahohai, painted by Jaycee Nahohai, 2014. Earthenware. H. 4 3/4". (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Jar, Randy Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2014. Earthenware. H. 8 1/4". (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Glaze-painted pottery from surface at Hawikuh. (Photo, Paul Diehl.)

Glaze-painted jar, Jaycee Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2015. Earthenware. H. 8 3/8". (Photo, Edward Chappell.)

Offering bowls, Jaycee Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2015. Earthenware. D. 5 1/2". (Photo, Edward Chappell.) The bowl on the left is glaze-painted.

Cornmeal bowl, Milford Nahohai, Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico, 2004. Earthenware. W. 6". (Photo, Edward Chappell.) This bowl represents his brief influence from Australia, which he had visited.

Zuni water jar, 1880–1895, brought by George Coleman from Gallup, New Mexico, to Williamsburg, Virginia. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; photo, Willie Graham.)

Bookshelves overflow with publications about Native American pottery from the southwestern United States. A few extol the work of the region’s celebrity potters. More, including some of the earliest and most comprehensive, are broadly conceived cultural studies that use archaeological collections to trace the movements of ancient populations, developments in their technologies, and the reach of their trading networks. The following study of potters in the modern Zuni Pueblo draws connections with this larger, older tradition of scholarship. It does something else besides. By working with a contemporary family of Zuni potters—the Nahohais—I have had the privilege to observe how elements of a larger culture take shape piece by piece, pot by pot, brushstroke by brushstroke, influenced by values shared by parents, children, and kin as well as by choices, sometimes idiosyncratic and creative, made by the artists themselves when they press their thumbs into a lump of clay or dip a brush into a dish of paint. Culture, magnified by biography, comes alive. But living traditions come from the past. So that first.

Historical Context

Early in the twentieth century Zuni potters found their rhythm of life and structures of commerce altered by the advent of the railroad. Soon after the trains started arriving, these potters—virtually all women—began making the forty-mile trek by wagon from their village on high, rocky land just west of the Continental Divide to the scruffy mining and rail town of Gallup, New Mexico, east of the Arizona line and 150 miles west of the Rio Grande.[1] For them and other Native people, Gallup had grown to be both a benefit and a curse, a source of modest income and a center of unwanted foreign intrusion.

The A:shiwi potters, known to outsiders as Zunis, carefully packed their handsome newly made wares, along with a few old vessels, for the rough ride to the rail station. There, they briefly encountered buyers from another world, who communicated awkwardly in a different language but traveled with sufficient cash to spend on large souvenirs.

One of these self-confident foreign customers in the 1920s was George Coleman, a genteel Virginian who lived with his family in the rambling Williamsburg house his great-grandfather had built to overlook a market square in the old Tidewater town. Coleman treasured those local credentials, but he made his livelihood as Virginia’s commissioner of highways, and he sometimes traveled far, occasionally on the transcontinental railway.

Coleman stepped off the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe train in Gallup and joined others gesturing and talking among the Zuni women alongside the tracks until he had purchased three sizable water jars with thin, hand-coiled walls and rich ornamental painting. He paid little, probably about five dollars, and packed the jars so poorly that all three broke on the long ride back to Virginia. Still, such southwestern pottery was in fashion among well-traveled Americans in the 1920s, so his family glued the oldest and best jar back together and set it on the dining room cupboard (fig. 1). It remained there for more than half a century, a dramatic piece of exotica in a room filled with family portraits, old silver, and food prepared by generations of household servants.[2]

Coleman’s experience exemplifies much of the popular history of Native American art in the early twentieth century, particularly Pueblo pottery. As the story goes, touristic buying and art collecting replaced traditional use of family-made ethnographic objects, especially ceramics, because cheaply manufactured vessels sold to Indians made local production unnecessary in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. “Too much Tupperware,” potter Randy Nahohai (fig. 2) jokes, “was why Zuni pottery almost died out,” referring to the pattern of replacement by industrial products. It was a lucky alignment of developments that educated Arts and Crafts taste for handmade, locally or ethnically distinctive decorative arts rose to prominence as functional Native use declined.[3]

Museum professionals and anthropologists cultivated this popular interest in the name of science and education. Frank Hamilton Cushing and Matilda Coxe Stevenson, for example, focused primarily on Zuni as a supreme example of a distinctive Native community. Cushing and Stevenson both began publishing material in the 1880s that introduced Zuni to readers throughout the country and in Europe. They expressed paternalistic affection, and Cushing fought strenuously for Zuni land rights, while both scholars exoticized the people. Cushing in particular wrote popular accounts—such as the series “My Adventures in Zuñi,” published in Century Magazine—that were as much travel writing as ethnography and served as financial and political support for his scholarship (fig. 3).[4]

Cushing and Stevenson arrived at Zuni in 1879 as part of the first organized expedition mounted by the nascent Bureau of Ethnology (hereafter BAE, although it did not officially become the Bureau of American Ethnology until 1897) and led by Colonel James Stevenson, Matilda Stevenson’s husband. John Wesley Powell had visited Zuni and the Hopi mesas in 1873, and as bureau director he initiated this and subsequent expeditions with the purpose of collecting material from the pueblos before it disappeared into the hands of “visitors and speculators.” The Stevensons acquired vast quantities, sending some five thousand Zuni pottery objects to the BAE in 1879 and on two subsequent visits, at a time when the total Zuni population was less than two thousand.[5] The railroad made such large-scale and rapid transfer possible.

Cushing, too, was involved in the acquisition of Zuni objects for museums as far away as Germany, as European as well as North American museums vied for Native American objects from what they viewed as a rapidly diminishing pool of goods.[6] But the ethnologists’ aim was broader than mass consumption of picturesque ceramics and other artifacts. Stevenson, Cushing, and the BAE were motivated and directed by a newly focused evolutionary view of human history developed by Lewis Henry Morgan that cast such tribes in an especially important light. In 1877, inspired by Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution and natural selection, Morgan advanced the paradigm that all human progress developed through comparable stages, from “Lower Savagery” through “Upper Barbarism” toward “Civilization,” and that study of non-industrialized societies could help explicate human history in general.[7]

Communities like the Pueblos of New Mexico and Arizona, Morgan’s apostles argued, could stand in proxy for the stages through which Europeans had developed long ago. Study of such peoples was a pressing need because expansion of industrialized populations, like those of English-speaking America, severely threatened the purity and even survival of Native culture.[8] The BAE fieldworkers, then, were involved in what is now called “salvage ethnography,” out to harvest all the information and material culture that embodied the character of the people.[9]

Physical art forms, as well as spiritual beliefs and their ceremonial systems, were high on the agenda for recording. Zuni art and belief systems were distinctive among the Pueblos and both were seen as having great potential as evidence linking living Pueblo people with the predecessors who had left dramatic archaeological remains throughout much of the Southwest. The competitive Stevenson and Cushing viewed comparative study of Pueblo pottery as offering graspable links in a chain leading back into North American prehistory.[10] There was a certain nationalistic mandate to the quest, establishing an impressive antiquity for the country. As photographer Edward Curtis wrote two decades later, “You, who say there is nothing old in our country, turn your eyes for one year from Europe and go to the land of an ancient primitive civilization. The trails are rarely traveled, and you will go again” (fig. 4).[11]

Located far from cities and the Rio Grande, Zuni was seen as having a particularly complex and unaltered ceremonial culture. Cushing suggested that no ethnographic resource in North America, perhaps in the world, was richer in uncollected material than the Pueblos, and that Zuni was their “highest representative.” Religious belief, the “inner life of the Pueblos,” he argued, formed the deep framework of the people’s material life. Cushing, a rural New Yorker, slowly ingratiated himself into belief-based groups at Zuni in order to learn hidden ways, and Matilda Stevenson assertively recorded ceremonies and their accoutrements.[12] Much influenced by Cushing, Stewart Culin, prominent ethnology curator at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences (now the Brooklyn Museum), made Zuni ceremonial materials, textiles, and pottery making the central elements in the museum’s iconic 1905 Hall of the Southwest.[13]

Such aggressive collecting and recording of religious belief and ceremonial systems created problems in a culture where control of esoteric knowledge and avoidance of intrusion on ceremony are fundamental. Practical motivations for secrecy grew as the national government increasingly imposed assimilationist schools and land distribution on Zuni and other Pueblos. In this context, past archaeological excavation at Zuni ancestral sites is now recognized as colonialism.[14] Extensive digging at the circa 1450–1680 village of Hawikuh and roughly a thousand of its graves by Frederick Hodge for the Heye Foundation in 1917–1923 increased resentment, even as it provided hard-currency jobs for Zuni men and artistic resources for later potters. That resentment has endured, with growing popular intrusion into pre-solstice Shalako ceremonies, the elaborate winter ritual that brings Zunis home to the Middle Place and ensures prosperity for the coming year.[15]

In recent decades the Pueblo of Zuni has employed its own anthropologists and archaeologists, as well as sponsored excavation in the town that contributes depth to seriation of ancestral pottery.[16] This is happening in the context of anthropologists in general working to support Pueblo interests while avoiding appropriation of sacred knowledge and objects.[17] Zuni leadership has crafted a consensus on repatriation of particular religious objects from such museums as the Smithsonian Institution and Denver Art Museum.[18] Zuni elder Octavius Seowtewa, aided by Denver anthropologist Chip Colwell, recently traveled to London, Paris, Berlin, and elsewhere to ask more recalcitrant European museums to return War God effigies taken from sacred shrines.[19] The A:shiwi A:wan Museum has successfully mediated exchanges between many of the Zunis and outsiders at the Pueblo, although there was substantial community sentiment that the museum should be located at some distance from the town.[20] There is, then, a spectrum of outlooks among Zunis regarding access to cultural information, and it is a basic responsibility of all non-Zuni visitors, myself included, not to pursue or circulate controlled spiritual knowledge.[21]

Much Zuni pottery, when closely observed, raises important questions about the principal forces that have affected its making since the era of Cushing and Stevenson. Beyond that, there is value in studying how small groups of Zunis have developed their pottery and its uses over the last half century, within the modern Pueblo world. The potters’ circle at the center of this article is a single extended family, the Nahohais, who have learned primarily from one another and by examining older pottery and anthropological publications. I focus on a principal innovator, Randy Nahohai, while seeing creativity and skillful performance in other family members: mother, siblings, wife, son, and nephews. Randy Nahohai has made his own rules while working to sustain the distinctiveness of his community, a small, culturally unified society that seeks to maintain degrees of separateness in contemporary society, especially in spiritual matters. The story suggests that the potters who looked backward most intensely are also those who pushed the art form forward most dramatically. This group of artists has both broadened the range of fine pottery produced at Zuni and cultivated popular respect, inside and outside the community.[22] By better understanding these local perspectives, we can more thoughtfully judge the values outsiders have assigned to Pueblo pottery, and more broadly to what are often called ethnic or folk arts. If the work blurs boundaries traditionally assigned to these fields, that blurriness reflects present reality and that of the future. Such categories are decreasingly relevant and useful.

This study is primarily based on conversations with the Nahohai and Kalestewa families and on observation of their work. Our discussions began at Zuni in 1987 and grew more frequent and intensive after 2007. I do not substantially address the potters who primarily learned their techniques in school, as theirs is a somewhat separate story.[23]

PART I

Zuni Polychrome

The shaping and painting of pottery were remarkably varied among the Pueblos in the nineteenth century, and none was more distinctive than Zuni pottery.[24] By then, the work of Zuni potters had evolved into a number of distinctive forms, painted in characteristic ways, which led scholars and collectors to call the work Zuni Polychrome. Rather arbitrarily, some of those authorities see Zuni Polychrome as ending about 1920.

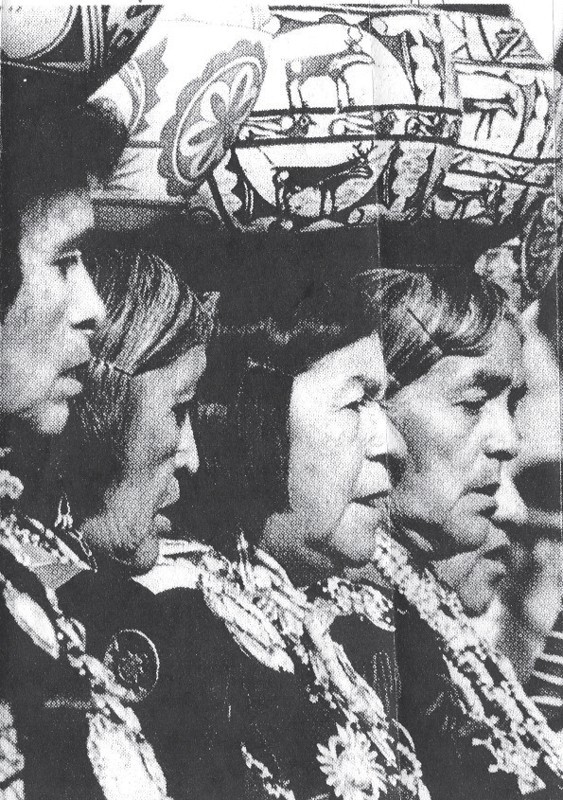

Most visually impressive were large water jars called ollas in Spanish and tinajas in Shiwi’ma (Zuni language), according to Cushing in 1879, and kāh’-wi-nā-kä-tehl-le according to the 1883 catalog for the Smithsonian.[25] Nearly all the jars had well-defined tripartite shapes: a round body between an outward-curving neck and a narrow base shaped like a truncated cone. Photographs and a handful of early films show Zuni women filling such jars with four to six gallons of water, then balancing them on their heads to carry them from the river or spring to their house. The rich ornamental quality of the vessel distinguished its bearer, quietly shaping an identity based on the skill of the potter.[26] Conversely, the women carrying high the great jars through the Pueblo brought a visual unity to the community, like the specialized dress of Zuni dancers at ceremonies in the plazas (fig. 5).[27] Graceful movement was a challenging skill that involved climbing ladders up multiple stories and descending through hatchways, requiring a different training from that of the dancers.

Upper openings of simpler globular jars were covered with leather and used by Zuni men as drums, te/-peja, and others without bottoms were stacked, one above the other, and used as chimneys rising from the flat roofs of the town (fig. 6).[28] Smaller pottery canteens followed mammiform shapes that Cushing interpreted as having more than passing resemblance to women’s breasts.[29] Randy Nahohai calls the canteen meh-heh’doh.[30]

Potters also made bowls in simple round shapes with convex sides and straight or outwardly turned rims as vessels for preparing and serving food. Cushing, Stevenson, and recent scholars have observed three general sizes of bowls made circa 1875–1885, the smallest sometimes identified as vessels for individual food consumption, which Randy Nahohai and his son Jaycee call sa’tsa’nah.[31] Zunis ate from shared stew bowls in the late nineteenth century, and the broad vessels had ritualistic as well as functional roles when they were used to carry food to participants in religious ceremonies.[32] Jaycee calls these ma’si-ya’kya sa’weh or sa’leh.[33] The largest—more than sixteen inches in diameter—were used for bread making after the Spanish introduction of wheat. Randy characterizes the dough bowl as “like an aluminum tub” and calls it mo-tsa-ash-na-kya sa-le.[34]

Equally distinctive in shape as the great tripartite jars are smaller terraced bowls: broadly proportioned vessels with stepped sides or round bumps representing the landscape of Zuni (fig. 7). Cushing related the belief that Earth Mother brought form to the world as a great terraced bowl, and that the Zuni world remains like an offering bowl “terraced with mountains, whence rise the clouds.”[35] In English, Randy Nahohai refers to the form as “cloud bowl,” and his brother Milford calls the bowl a-wetuyaba sa’le.[36] Terraced bowls played integral roles in Zuni ceremonial life by the time Cushing and the Stevensons intruded on such scenes.[37] The general absence of terraced bowls from excavated seventeenth-century archaeological deposits indicates a post-Pueblo Revolt (1680–1692) evolution in at least some accoutrements of religious offerings and medical intercession. One wonders which contributed more to a change toward such distinctive vessel shapes: the introduction of the form through displacement of other Pueblo peoples, or the later lessening of Roman Catholic control.[38] A better understanding of when Zuni potters began making the bowls awaits more excavation in the present town.

Motifs painted on the vessels varied according to their form and function. Outsiders associating Native American motifs with names, meanings, and spiritual purpose is a long-debated exercise, one now as often attributed to cultivating sales to non-Native buyers as to actual beliefs. Early anthropologist Jesse Fewkes called it “picture writing.”[39] Romanticized explanations for design elements extend well beyond Native American material culture, as when everyday preindustrial Anglo-American building components are ascribed to religious beliefs, nautical construction, or mortgage status.[40] Pueblo pottery scholars Dwight Lanmon and Francis Harlow were especially prudent in avoiding most interpretations of meaning in their monumental study of Zuni Polychrome pottery and its origins.[41] This article takes a somewhat riskier route because it is more focused on the purposes and thoughts of contemporary makers, to the degree they are shared.[42] Cushing, Stevenson, and their successors observed that Zuni culture was so rich and its belief systems so intact that interpretations of motifs have validity, even if they vary over time and among individuals.[43] Much of that culture and its beliefs still flourish.

Into the twentieth century, too, there was a clear division between motifs used for different sorts of vessels, dependent on use. In the 1920s anthropologist Ruth Bunzel wrote that “The cleavage between household and ceremonial objects in regard to form and decoration is so complete that it is difficult to believe that two such different ceramic types belong to the same age and the same people.”[44] Motif selection, then, was not random. Drums were unornamented or painted with rattlesnakes and large mammals such as bears or mountain lions associated with the medicine society, on a plain background.[45] Terraced bowls were usually painted with depictions of frogs, tadpoles, dragonflies, sometimes butterflies, and the mythic water serpents called Kolowisi. Bunzel observed that these figures were crudely painted on a plain white field without any of “the carefully integrated structure that characterizes the household pottery.”[46] Rather, their structure was more often contextual, as the vessels took up prescribed positions in ceremonial spaces that also contained colorful altars, figural wall paintings, supplicatory floor patterns, and other objects of spiritual use. Terraces on altar posts and elements hung from chamber ceilings reflected the silhouettes of the bowls.

With encouragement and direction from Franz Boas, Bunzel came to Zuni initially to study women’s work, subscribing to the view that “society consisted of more than old men with long memories.”[47] She referred to decorated domestic vessels as household art worthy of greater care by the makers, who most often were also the users. Nineteenth-century drawings and photographs show the striking vessels in rooms of houses virtually unornamented otherwise, contrasting with ceremonial space (figs. 8, 9). Like ceremonial vessels, jars for transporting and storing water and bowls for food preparation or eating were overwhelmingly slipped with a white surface. From the nineteenth century into the twentieth, Zuni potters painted the recessed lower segment of their water jars a darker color (first orange or red, later primarily brown-black). This continued the late-eighteenth-century tradition, now called Kiapkwa Polychrome, contrasting with the application of orange paint to the unarticulated lower segment of Acoma, Laguna, and Zia Pueblo jars.[48] Zuni potters painted motifs on the upper two segments, with independent neck patterns separated from the protruding belly by one or more heavy horizontal lines.[49] Into the twentieth century such segregating lines above and below the belly were usually interrupted by a small break.[50] I call these principal horizontal lines “boundary lines.”

On these, the most publicly used vessels, potters painted the principal canvas in a number of compositions. One approach was to wrap an overall pattern around the full circumference of the belly. Another was to divide the belly into horizontal and vertical registers, which could be roughly rectangular, or an unboxed series of circles, crooks, or other motifs alternating with large rosettes, conceivably inspired by geometric rosettes common in European-American (including Hispanic) decorative arts.[51] The belly pattern often consisted of crook-and-scroll compositions, the crooks sometimes taking the form of a stylized, coiled head of a bird. Most prominently, and often copied by late-nineteenth- and twentieth-century potters at eastern Pueblos, especially Acoma, the belly was painted with depictions of deer, seen in profile, with a red arrow extending into their mouths, a convention associated with the animals’ sacred breath, which was respected by Zuni hunters.[52]

Potters painted the exterior of large stew bowls with many of the more geometric domestic motifs, which were highly visible when women carried these vessels, too, on their heads, among the largely unornamented buildings at Zuni. The potters painted canteens and the interiors of round food bowls for domestic use with similar motifs. Heavy boundary lines, again with a break, commonly separate a relatively narrow upper zone of bowl interiors, like the lines marking the shoulders of water jars. Crook, scroll, and other motifs are often arranged around a central circle, square, or concave diamond shape. Concentration of ornament on the inside of bowls reflects the fact that most often they were placed on the floor or other low surfaces and viewed from above. Drums were left blank or painted with one or more aggressive species of animal on a plain field. Purely utilitarian cooking pots (which by the 1880s were being replaced by a trade in metal vessels) and those favored for chimneys were typically left unslipped and undecorated.[53]

Extreme Contact

Both the production and use of Zuni pottery were jolted by exposure to the modern world beginning in the late nineteenth century, and to some degree the responses have paralleled developments at other Pueblos. The picturesque Southwest became a commodity for artists and travelers, with Santa Fe and the northern Pueblo of Taos playing central roles.[54] Santa Fe reinvented itself as a regional destination for leisure travel by developing an architectural vocabulary that drew on the urban massing of existing Pueblo communities such as Acoma, Taos, and Zuni, and on endemic details like adobe walls and projecting vigas (joists) below plastered flat roofs. Developers and Anglo designers appropriated Pueblo art forms for their new or historicized old buildings.[55] Hotels came to resemble Zuni architecture shorn of its trap doors, ladders, and mica-glazed windows just as such details were disappearing from the village. Firms such as the Fred Harvey Company provided tours to genuine Pueblos, making it easier to meet real Indians and buy products of their culture, especially pottery. Zuni was far from the tourist centers, but that remoteness strengthened its appeal for certain travelers.[56]

The interest and purchasing power of such visitors, dealers, and museums has had a powerful impact on Pueblo pottery that has varied among the communities according to the degree of outsider access, individual talent, and the attitude of the makers toward the often aggressive Anglo market. Pottery not purchased by museum collectors was literally stacked up by traders and offered in retail store windows like factory-made merchandise (fig. 10). Curio merchants commonly bought the cheapest goods from local dealers and sold them nationwide as handicrafts appropriate for middle-class houses.[57] In response, perceptions of authenticity—that is, based on what was made for traditional use as opposed to what was made for sale to outsiders—offered a criterion by which scholars and the educated Anglo public judged and influenced the work of many potters, especially at the eastern Pueblos.

Regional preservationists and anthropologists played influential roles, seeking to stimulate Pueblo arts, create a more discerning market, and maintain or improve quality as they saw it. Styling himself an “art archaeologist,” Kenneth Chapman at the Museum of New Mexico and later at the Laboratory of Anthropology in Santa Fe carefully drew and categorized painted Pueblo pottery designs such as Zuni bird motifs as a means of preserving and cultivating regional Southwest culture.[58] He applied art connoisseurship to San Ildefonso and Kewa (then Santo Domingo) pottery, for example, evaluating which designs were the most skillfully executed and dynamic.[59] Chapman and others helped change public perception of Pueblo pottery from the classification of ethnographic objects, or curios, to art, reflecting a more universal early-twentieth-century fascination with nonacademic art and abstract painting (fig. 11).[60]

Ironically, the cultivation of popular taste for what was considered ethnic or vernacular art often carried strictures in the cause of authenticity. Throughout much of the world, from Yucatan to the White Sea, a strong modern perception has been that folk culture is largely static, varying more across regions than over time. Such interest especially resonated in the United States in the 1920s and 1930s, when, in a time of economic turmoil, Americans sought stability and elites were discomforted by the growth of immigrant populations. Seeking purity of traditions, scholars of folk music pursued what they viewed as intact, anonymous English and Scottish ballads. Soon the search for ballads unspoiled by publication extended to American enclaves distant from industry and worldly education, such as the southern Appalachian Mountains.[61] African-American and Native American folkways were seen as comparable or richer than the scattered British relics, and worthy of recording while they survived alongside industrializing America. Like restoring Spanish missions and old New England houses, cultivating Native American arts was important to sustaining the personality of those regions for what was considered the public good.

In the Southwest, championing authenticity in Native pottery contributed to an idealized conception of Pueblo life used to fashion an appealing regional identity that would attract outsiders.[62] Artistically engaged members of the Anglo Santa Fe community did seek to protect Pueblo culture and landholdings by promoting what they viewed as authentic Native art, particularly painting.[63] But one can also consider this in systemic political terms, beyond local circumstances. Literature and anthropology professor Barbara Babcock identifies demands for “authenticity” in Native craftwork and efforts to lock Pueblo people and other Native Americans into an ethnographic package as mechanisms for managing them into peaceful supporting roles for the larger society.[64]

In the still influential book Patterns of Culture (1934), anthropologist Ruth Benedict used a Nietzschean model to portray Zunis as Apollonian—communal, peaceful, even passive—in comparison with Dionysian Native Americans of the Plains and Northwest Coast. Their harmonious personality defined their urban culture, a culture that left impressive monuments from the past. For the reading Anglo public it was a seductive stereotype, whether projected back on Pueblo ancestors or applied to the living. Benedict’s conflict-free characterization has been substantially challenged, even if Zuni attitude does suppress aggrandizers. Archaeologist Stephen Lekson skewers what he calls the “Benedictine Fallacy” that Pueblo culture was timeless and universally harmonious, but it sells well nevertheless.[65]

Conceptions of authenticity have often been focused on continuing preindustrial Pueblo production methods as well as shapes and painting morphologies dating from the late nineteenth century. Archaeological excavations have uncovered long histories of particular patterns and extensive evolution well before first contact with Europeans. Anthropologist Bruce Bernstein inverts the popular view to suggest that the chief tradition of Pueblo pottery is, in fact, change.[66] Change in precontact pottery making was sometimes rapid, with entire styles morphing and disappearing. Change appears to have accelerated in the era of violent contact with Spanish soldiers and mission builders. As early as 1939, H. P. Mera hypothesized that the oppressive Spanish encomienda labor system disrupted populations to such an extent that pottery styles were diffused among the Pueblos.[67] Archaeologist Barbara Mills sees increased use of Puebloan ceremonial motifs on Zuni ancestral pottery from the missionization era before the Pueblo Revolt, beginning in 1680, and a broad shift to more abstracted feather motifs as well as more subtle changes in materials acquisition and production as the Zuni population declined and the number of substantial villages dropped from as many as eight to one. Mills posits that Zuni potters made a rapid, intentional change to vessels much closer in appearance to nineteenth-century Zuni pottery, when repopulating that single village circa 1680–1700.[68] J. J. Brody points to broader Pueblo loading of abstract ritual imagery onto pottery as the people experienced the diseases, religious intolerance, and administrative oppression brought by Europeans.[69] In less than a decade following the Stevensons’ first collecting in 1879, Mills and anthropologist Margaret Ann Hardin observed a simplification in the painted decoration of small eating bowls at Zuni. The change could reflect a decline in the concentration of traditional knowledge due to the loss or destruction of some of the best models and the death of older, skilled potters from a smallpox epidemic caused by Mormon settlers, as well as production for a new external market, including the Smithsonian, thought to favor a certain variety of work.[70]

In spite of abundant evidence of long-term change in Southwest pottery, already evident in the 1920s, sophisticated consumers considered Zuni Polychrome and contemporary traditions at other Pueblos as authentic objects against which new work could be critiqued. Such rarefied taste as well as the tourist market affected what people made, but personal and community preferences dominate when a broader story of Pueblo pottery-making is told, or certainly this is so in Zuni.

Chapman and other self-appointed cultural managers significantly helped Pueblo potters do thoughtful, careful work and cultivated public respect for certain potters. Together, reflecting on what design methods in old pottery could best direct new work, the potters and their facilitators created a recognized canon of contemporary Pueblo pottery, a solid base from which later artists could develop. The canon also perpetuated standards that placed hurdles in the careers of innovators and modest potters who simply disagreed. Hardin observes that potters like the Nahohai family had to overcome potentially crippling categories by which dealers and administrators judged Zuni pottery at the great Santa Fe Indian Markets (previously called Fairs) into the 1980s. Traditional outdoor firing was a common request. The younger potters drew their own lessons from old work and chose self-determination rather than take direction from what Randy Nahohai gently refers to as “the experts.” He breezily dismisses the challenges, remarking that his chief innovation at the Indian Market was to sell broken pots.[71]

Old and New Traditions: Pueblo Context

For more than a century Pueblo potters have preserved, recaptured, or created traditions, often under the surveillance of connoisseurs and critics. They have increasingly developed and altered traditions through individual choice rather than from ignorance of alternatives. Classroom education and exposure to electronic media and modern materials have liberated artists’ options, even when institutional training sought to limit what it defined as the acceptable oeuvre. Some innovators have enlivened or initiated durable traditions that have drawn fellow artists into constructing specific Pueblo styles, and others have seen no substantial response from their communities. Much of this evolution has been undeniably market-based. As we will see at Zuni, however, the market is not entirely external nor is the choice of designs so controlled by outsiders.

First, modern developments at selected other Pueblos provide some context for individuals and families engaging with a cash economy while sustaining Pueblo identity, often on their own terms. Most famous is Nampeyo (ca. 1856–1942), a Tewa potter at the tiny village of Hano on First Mesa in eastern Arizona, who developed a pottery style in the 1890s that drew on precontact Sikyatki Polychrome pottery with energetic geometric and bird motifs that had influenced ancestral Zuni pottery. Polacca Polychrome wares were influenced by later Zuni pottery, or at least the two shared motifs, and the wares had become standard for Hopi and Tewa people on the Arizona mesas circa 1780–1890. Nampeyo’s earth-tone colors and distinctive freehand ornamentation made hers the first modern revival Pueblo pottery desired as furnishings for Arts and Crafts, Mission, and similarly themed houses being built for the growing number of middle-class families. Nampeyo demonstrated pottery making and stayed with her family members at Fred Harvey Company’s faux Pueblo Hopi House at the Grand Canyon in 1905–1907 and in Chicago in 1910. The market for her pottery fluctuated, and she lived a modest life on the mesa, without modern amenities or command of the English language. She founded a dynasty of potters who have continued working in her revival style and retained her name into the fifth and sixth generations.[72] One of her granddaughters, Daisy Hooee (1906–1994), traveled internationally, studied art at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and in the 1960s became the second person (and first non-Zuni) to teach Pueblo pottery-making at Zuni High School, shifting from Hano Polychrome to Zuni Polychrome motifs (fig. 12).[73]

Near Santa Fe, Maria Martinez (1887–1980) and her husband Julian (1879–1943) made the first eastern Pueblo pottery widely recognized as art. After developing polychrome pottery drawn from the late-nineteenth-century San Ildefonso tradition, they worked in consultation with archaeologist Edgar Hewett on pottery informed by earlier wares excavated at Bandelier National Monument (although the difficult Hewett claimed more influence than he provided). In 1919–1920 they began making smooth-surfaced, black-on-black pottery (blackware) by smothering their manure-fueled fire to create a reduction atmosphere. Before firing, Maria burnished the body to a high gloss, and Julian painted it with black slip, drawing on diverse ancestral and contemporary Native American sources, including Zuni and Hano Polychrome.[74] The result—matte black designs on supremely polished black pottery—had great appeal to the Anglo population in an era when Native American–themed motifs were common in stylized classical and Art Deco designs and a certain reserve in figural ornament was valued in machine-finished material. Making some of their blackware as plates and other European-American forms increased its desirability in the popular market. Maria, her family, and her followers, as well as the Tafoya family at Santa Clara, have made great quantities of refined black pottery, which continues to appeal to buyers with urbane and often Modernist taste.[75] The growing fame of both families and their proximity to Santa Fe allowed them to sell much of their pottery directly to tourists and collectors, bringing substantial income to their communities They, like Nampeyo and her family, developed means of entering the cash economy while living and working in their Pueblo communities and continuing to play major, traditional, community roles. This provided a model for other matriarchs and their families, among them that of Lucy M. Lewis at Acoma.[76]

Never in the twentieth century did Acoma pottery slip from the public view, and there have long been more potters from Acoma than any other Pueblo. Within that context, though, Lucy M. Lewis (1902/5–1992) attained a high standard of work. At mid-century she employed a number of painted designs inspired by or borrowed from precontact Mimbres, Tularosa, and Hohokam pottery, as well as nineteenth-century Zuni Polychrome, all of which she saw in publications and in Santa Fe museum collections. Mimbres is especially worthy of brief explanation because it became such a recurring influence on Southwest potters when it was excavated in the twentieth century. Mimbres women were part of the larger Mogollan group and lived in present-day Southwestern New Mexico from about 1000 to 1250. They painted domestic and funerary bowls with such imaginative human, animal, and geometric compositions that they now seem the wittiest of Native American ancestors, whatever the ancient artists’ intended meaning.[77] Lucy Lewis’s daughters Emma Lewis Mitchell and Dolores Lewis Garcia and other descendants have perpetuated the clarity of her figural design, painting in black or black and red on white slipped vessels.[78] The family has exhibited its pottery at Santa Fe Indian Markets since 1960, where their friendship has encouraged non-Acoma potters, including the Nahohais.

Many talented Pueblo women worked successfully without fame and generous income. The style of Santa Ana pottery diverged in the nineteenth century from that of nearby Zia to production of bowls and globular jars painted with robust abstract motifs. There was little market for new Santa Ana pottery in the early railway era, and the number of potters dropped nearly to zero between about 1910 and the 1940s. Potter Eudora Montoya (1905–1996) was most active in reviving Santa Ana work about 1946, making thick-walled, white-slipped pots that she or her husband painted with elemental brown or black and red motifs, roughly rendered in slips that she sometimes acquired from sources other than those her ancestors had used, such as white kaolin she bought from Zia (fig. 13). Among her motifs were ones Kenneth Chapman showed her on what he believed were the best old Santa Ana pots previously acquired at the Pueblo. The amount of work declined in the 1950s and 1960s but was revived when Montoya taught pottery making to other Santa Ana women in 1973. It was revived once again in the 1990s by those taught by Montoya, and a small group of women potters now keep the tradition alive.[79]

As bland postwar American popular taste broadened and Pueblo pottery-making became somewhat more profitable by the 1970s, more men took up the trade. In the 1990s, after first painting mass-produced greenware, John Montoya created a lively revival idiom in hand-coiled pottery at Sandia, a Pueblo without a recent tradition of ornamental pottery. He drew on varied sources to make Acoma-like jar shapes, figures reminiscent of Zuni owls, and vases resembling precontact cylinders excavated at Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon. He painted all these with geometric rock art motifs and Mimbres renderings of small animals as well as popular Native American images of plants, feathers, and rainstorms (fig. 14). He often added naturalistic portraits of larger mammals and mountain landscapes. Painting with gray and soft brown on pinkish white slips, he covered every surface of his vessels, some nearly two feet tall. He talked of moving to Japan and opening a Native American art store, but died unexpectedly about 2004 and no one has substantially followed his pottery-making lead.[80]

Kewa has been viewed as a particularly conservative Pueblo whose pottery changed relatively little in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Its potters remained active primarily for Pueblo use into the twentieth century, but some of them defied Native leaders by selling pottery in Santa Fe Indian Fairs in the 1920s, led by Monica Silva from Santa Clara, who had married a Kewa man. By the 1980s Robert Tenorio (b. 1950) was most prominent among contemporary Kewa potters, turning to traditional methods with help from his grandmother Andrea Ortiz and great-aunt Lupe Tenorio after first studying jewelry making and stoneware pottery at Santa Fe’s Institute of American Indian Arts in the late 1960s. Using shadowy black and orange on a cream ground, he often combines traditional Kewa geometric motifs with animal portraits appealing to non-Pueblo collectors (fig. 15, center). His sisters and his nephew William Andrew Pacheco began working in a comparable manner, Pacheco beginning as a teenager to paint dinosaurs on jars and plates about 1990 and continuing to work with wry imagery within the developing family idiom (fig. 15, right and left).[81]

The contemporary art market for work by living Pueblo potters has shifted to favor what could be called ironists over straight traditionalists. Among the most commercially successful potters of recent decades have been men and women who mixed elements of revival style with contemporary individualized expression. One of the most creative is Diego Romero (b. 1964), who paints semi-spherical bowls with narrative scenes in a manner that draws on classical and cartoon art as well as Mimbres pottery. Most often the artist uses Mimbres-inspired figures to portray, with humor and pathos, current Native Americans living in a strange modern world (fig. 16, right and left). Romero lived in Berkeley and Cochiti and studied art at UCLA and the Institute of American Indian Arts. He addresses contemporary issues and popular art using revival idioms in such an engaging way that every self-respecting museum showing Native American art must exhibit one of his bowls. Museums tend to favor his savvy portraits of present-day Native life and reinterpretations of comic book images over his explicit anticolonial and (rarer) sexual scenes.[82] As familiar with European-American art and pop graphics as he is with Southwest pottery, Romero’s smart use of gold, green, and other unexpected colors in combination with traditional Pueblo pottery hues shows that he makes his choices knowingly.

His brother and sometime collaborator artist Mateo Romero (b. 1966) cites their grandmother Teresita Romero’s freewheeling Cochiti revival pottery with applied small animals (fig. 17) as the principal inspiration for his own politically assertive easel painting. In comparing her work with that of Diego Romero, one sees a refinement in execution that exemplifies much of the development in Pueblo pottery over the last half century. In 2012 Diego’s son Santiago Romero (b. 1987), educated at Dartmouth College, began making three-dimensional clay renderings of his father’s trickster coyotes and Desert Lylee, the family’s blue dog, acting out a second generation of antics.[83] Dressed in lightning-backed vest and wood-grain circuitboard-pattern pants, Desert Lylee is shown begging for food, symbolizing Pueblo people’s supplication, sacrifice, and restraint in perpetually pleading for rain (see fig. 16, center). Santiago moved on to geometric bird sculptures (doves, parrots, and quails by late 2014) inspired, he says, by the William Butler Yeats poem “The Second Coming,” which he interprets as a chaos of birds marking the rise or collapse of civilization.[84] All three Romeros unapologetically confront the loss of the innocence that Chapman’s generation of connoisseurs found beguiling in Pueblo art.

Just as earlier critics judged working Southwest potters by the degree to which they maintained or revived traditional methods and iconography, curators now celebrate only museum-anointed artists who break free from “restrictive inheritance” or recast tradition with angst or irony.[85] Hipster dealers regard (and promote) two varieties of Pueblo pottery as most desirable and expensive: that by living radicals and that by dead traditionalists. Especially with Zuni pottery, the highest commercial value is assigned to good work claimed to predate World War I, unless it is clearly by an identifiable later potter. There is no reason to accept these market-driven criteria as objectively valid. Doing so would be to ignore the perspective of a community that has long favored selective acceptance of outside ideas while staunchly defending its beliefs. Anthropologist James Ostler calls Zuni a cultural as well as a language isolate, suffering little concern for non-Zuni taste. Zuni artists are locally acknowledged when they excel within a niche, more by specialization than revolution, and excessive personal attention can be divisive in the community, or worse.[86] Ostler observed that the artists design primarily for a Zuni audience, even when their work is largely sold to outsiders.[87] Bernstein remarks that repetition can be as important as innovation.[88] There is sufficient honor in sustaining tradition.[89] This can itself involve creativity and change, embracing what appears to be a stronger as well as older mode of work.

Making Choices

Material culture scholars employing linguist Noam Chomsky’s cognitive models argue that members of traditional societies follow the rules of their culture unconsciously, based on cultural learning. When speaking, creating songs, or building houses, for example, individuals make choices that are diverse but grammatical, drawing on the performances of other speakers, singers, or builders with which they are familiar. “From birth the head is filled with constant sensations, a hum of sound, a shimmering of sights,” folklorist Henry Glassie remarked, from which the person derives a set of procedures used to structure his or her creations, whether formed by hand or mouth.[90] There remains room for change, as new models are introduced when necessary. Archaeologists are particularly interested in such changes evinced in the material record of the Southwest, long before as well as after contact with Europeans. All Pueblo communities sustained dramatic change when the Spanish invaders sought to alter their patterns of work and replace their systems of belief, and perhaps even more in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with modernization and political intervention threatening to erase much of their time-honored experience and introducing different, foreign models for nearly everything.

For Zunis and countless other groups, maintaining distinctive traditions has in the last two centuries become increasingly a matter of choice rather than performance within a limited grammar. Art or craftwork performed at home allows a certain “cocooning” that has helped preserve rituals and beliefs essential to Pueblo communities, but cocooning there represents selective shielding of practices and values rather than removal from all agents of mass culture. From Nampeyo to Diego Romero, artists have chosen to reinvent as well as preserve design elements that can represent both individual expressions and a shared aesthetic.[91] Zunis in particular have kept their pottery tradition alive through an era in which minority cultures worldwide have responded to radical change. Cultural survival, then, is a dynamic rather than static process. Beginning late in the last century, Randy Nahohai and other Zuni artists increasingly worked to reestablish and enrich the tradition within a community that has chosen to maintain a distinctive and complex web of practices and beliefs, especially spiritual ones.

Randy, we will see, has quietly set about constructing a coherent grammar of Zuni pottery over the last three decades, a grammar with shapes drawn from historic Zuni models, and with ornament inspired by a variety of sources, all of which resonate with his perception of the Zuni past. Much of his work can be seen as less overtly radical than that of Diego Romero and Santiago Romero, but certainly it is no less thoughtful. Looking at the spectrum of Randy’s work, one sees an extraordinary rigor in the development and use of his enhanced grammar. It is a rigor he applies only to himself—he seldom criticizes others for following different routes along their design careers—yet it is intended as an effort on behalf of the community, not for the artist’s satisfaction alone. A detailed look at twentieth-century Zuni pottery and the Nahohai family’s work is useful in understanding an art form that is changing within a culturally distinct society.