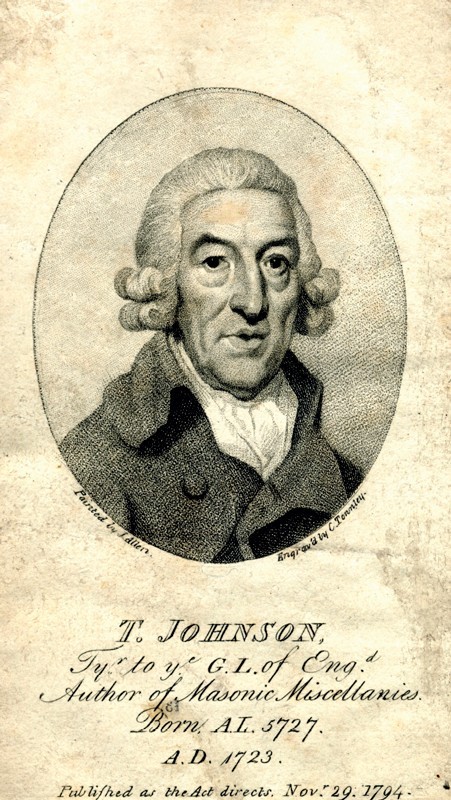

Charles Townley after Joseph Allen, Thomas Johnson, frontispiece in A Brief History of Freemasonry (2nd ed., 1784). (Courtesy, Library and Museum of Freemasonry, London.)

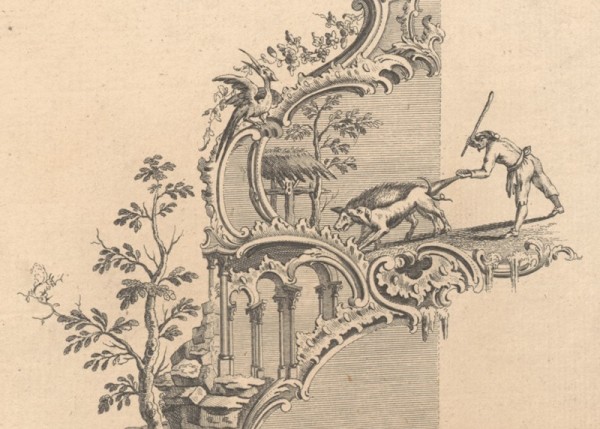

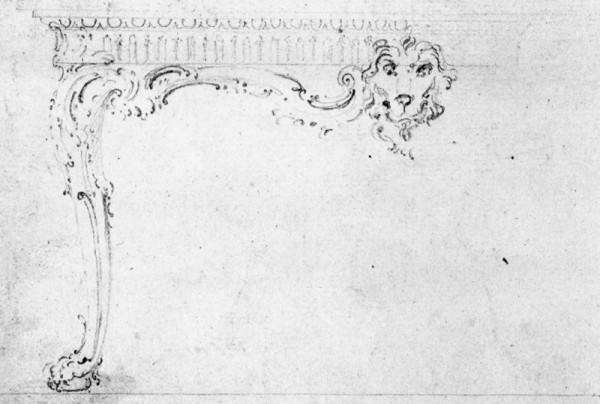

Thomas Johnson, “Contrast bracket to hold a small figure or busto,” London, 1793, from a design drawn in 1746. Etching and aquatint. (Thomas Johnson, The Life of the Author [1793]; courtesy, Library and Museum of Freemasonry.) Matthias Lock’s influence is evident in the drawing and posture of the dragon and style of the leafage, scrolls, and flowers. For related work by Lock, see his 1746 etching of a sideboard table in Peter Ward Jackson, English Furniture Designs of the Eighteenth Century (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1958), pl. 50.

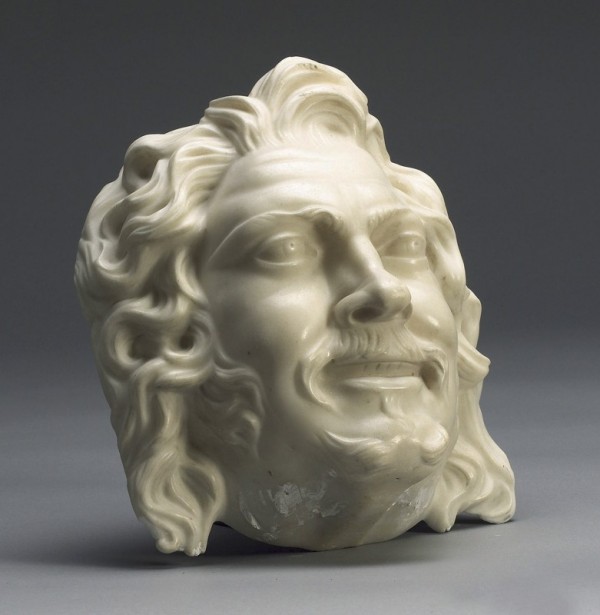

Portrait bust from a chimneypiece, attributed to John Houghton and stonecutter David Sheenhan, from Kenmare House, County Kerry, Ireland, ca. 1752. (Courtesy, Bonhams.)

Thomas Johnson, Girandole with “a ruinated building, with cattle, &c.,” London, 1793, from a design drawn in 1755. Etching and aquatint. (Thomas Johnson, The Life of the Author [1793]; courtesy, Library and Museum of Freemasonry.)

Girandole design attributed to Matthias Lock, London, ca. 1750. Pen and ink wash. 10" x 5 3/8". (© Victoria & Albert Museum; George Lock Collection.)

High chest of drawers with carving attributed to Bernard and Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770–1775. Mahogany with yellow pine, tulip poplar, and white cedar. H. 96 3/4", W. 45 1/2", D. 24 1/2". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Graydon Wood.) The carving on the chest and its matching dressing table is attributed to Bernard and Jugiez. Their firm advertised in several coastal cities and shipped carving as far south as Charleston, South Carolina. Bernard and Jugiez also did commission work for prominent Philadelphians, including Chief Justice Benjamin Chew, Samuel Powel, and John Cadwalader, and cabinetmakers, including Thomas Affleck. The carvers may have worked for Benjamin Randolph, who clearly had access to Johnson’s designs. On August 4, 1771, Nicholas Bernard received a note from Randolph for £40 “payable in Six Months wen paye Shall be in full” (Benjamin Randolph Receipt Book, Winterthur Museum).

Detail of the appliqué on the center drawer of the lower case of the high chest illustrated in fig. 6.

Detail of a design for a pier glass illustrated on pl. 21 in Thomas Johnson’s One Hundred & Fifty New Designs (London, 1761). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) Johnson sold his designs in installments between 1756 and 1757 and as collected editions in 1758 [untitled] and 1761 [titled]). Jacob Simon, “Thomas Johnson’s The Life of the Author,” Furniture History 39 [2003]: 10).

Parlor in Cloverfields, Queen Anne’s County, Maryland, ca. 1728, with carving installed ca. 1770. (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail of the chimneypiece appliqué illustrated in fig. 9.

Detail of the chimneypiece appliqué illustrated in fig. 9.

Detail of a design for a mirrored overmantel frame illustrated on plate 5 in Thomas Johnson’s One Hundred & Fifty New Designs (London, 1761). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Parlor from the Blackwell House, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, built ca. 1764. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The carving was probably installed between 1766 and 1770.

High chest of drawers with carving attributed to Hercules Courtenay, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1775. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with yellow pine, tulip poplar, and white cedar. H. 91 3/4", W. 44 5/8", D. 22 1/2". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Detail of the tablet on the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 13.

Design for a chimneypiece tablet illustrated on plate 3 on Thomas Johnson’s A New Book of Ornaments By Thos. Johnson Carver, Design’d for Tables & Frizes for Chimneypieces; Useful for Youth to Draw After (London, 1762). (© Victoria & Albert Museum.)

Detail of the drawer appliqué on the high chest illustrated in fig. 14.

Design for a chimneypiece tablet illustrated on plate 5 in Thomas Johnson’s A New Book of Ornaments By Thos. Johnson Carver, Design’d for Tables & Frizes for Chimneypieces; Useful for Youth to Draw After (London, 1762). (© Victoria & Albert Museum.)

Parlor from the Thomas Ringgold House, American, Chestertown, Maryland, ca. 1770. Carver: John Pollard. Carver: Hercules Courtenay. Maker: unknown builder/architect. Yellow pine and mahogany, King of Prussia marble. H. 119 1/4, W. 263, D. 201 1/2". (Courtesy, The Baltimore Museum of Art, purchased as the gift of Emma James Johnson in memory of her husband J. Hemsley Johnson, BMA1932.32.1; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the tablet of the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 19. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the right frieze appliqué on the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 19. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Design for a chimneypiece frieze illustrated on plate 2 in Thomas Johnson’s A New Book of Ornaments By Thos. Johnson Carver, Design’d for Tables & Frizes for Chimneypieces; Useful for Youth to Draw After (London, 1762). (© Victoria & Albert Museum.)

Detail of the right frieze appliqué on the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 13.

Detail of a pier-glass design illustrated on plate 43 in Thomas Johnson’s One Hundred & Fifty New Designs (London, 1761). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

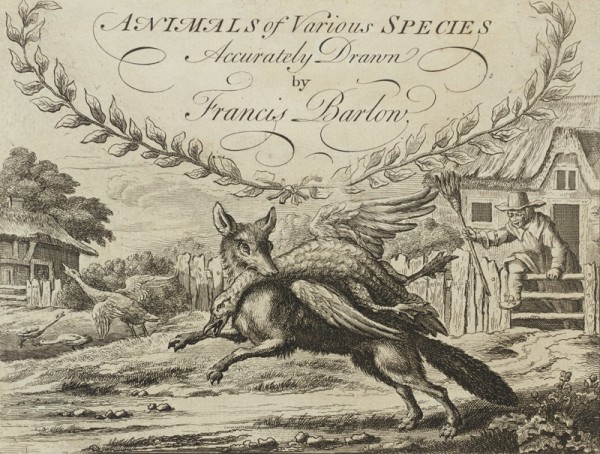

Title page of Animals of Various Species Accurately Drawn by Francis Barlow, part three of Various Birds and Beasts Drawn from the Life (London, ca. 1660–1670). (Courtesy, Tate Museum.)

Detail of the left frieze appliqué on the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 13.

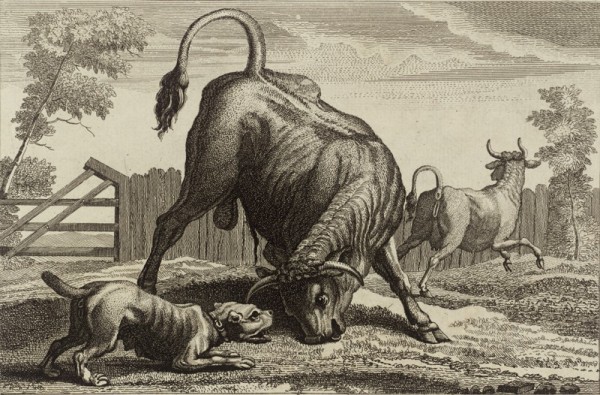

Plate 18 in Animals of Various Species Accurately Drawn by Francis Barlow, part three of Various Birds and Beasts Drawn from the Life (London, ca. 1660–1670). (Courtesy, Tate Museum.)

Detail of the tablet on the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 13.

Plate 21 in Animals of Various Species Accurately Drawn by Francis Barlow, part three of Various Birds and Beasts Drawn from the Life (London, ca. 1660–1670). (Courtesy, Tate Museum.)

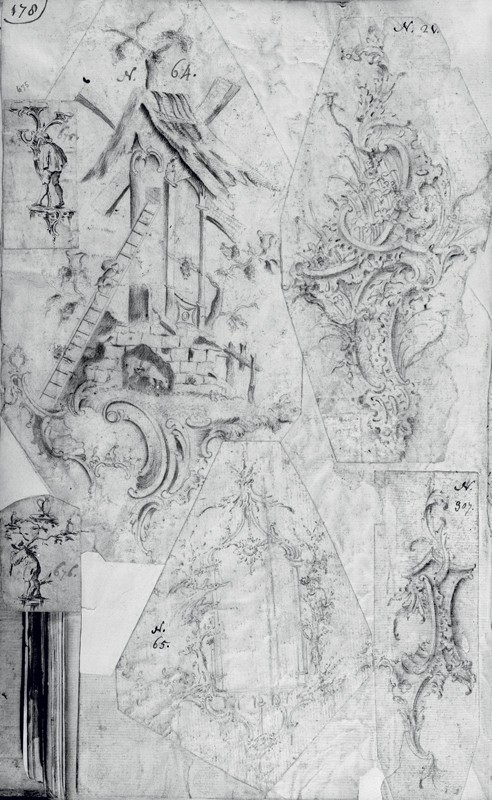

Designs for girandoles in the scrapbook of Gideon Saint, London, ca. 1765. (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art; photo, Art Resource.) These pages include engravings of Thomas Johnson’s designs as well as a pencil drawing of a girandole by Saint.

Drawings for looking-glass frames in the scrapbook of Gideon Saint, London, England, ca. 1765. (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art; photo, Art Resource.) Saint copied these designs from Matthias Lock’s A New Drawing Book of Ornaments, Shields, Compartments, Marks, &c. London, ca. 1746.

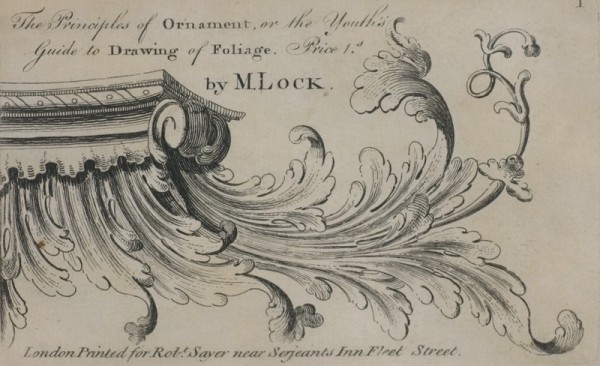

Title page of Matthias Lock’s The Principles of Ornament or the Youth’s Guide to Drawing of Foliage (London ca. 1746). (Chipstone Foundation.) This page is from Robert Sayer’s ca. 1768 reissue; no copy of the ca. 1746 publication is known.

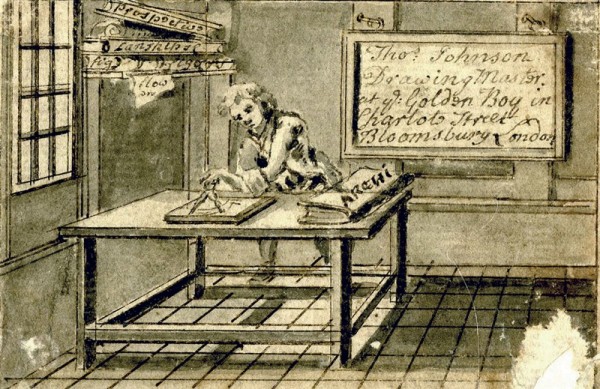

Thomas Johnson, design for a trade card, London, 1769–1775. Watercolor on paper. (© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.)

Chimneypiece from the parlor of the Samuel Powel House, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, built ca. 1765. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The carving was installed in 1770.

Detail of the right truss on the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 34. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Card table with carving attributed to Hercules Courtenay, 1765–1775. Mahogany with oak and yellow pine. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Mack Coffey.)

Detail of the knee carving on the card table illustrated in fig. 36.

Detail of the tablet of the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 34.

James Kirk (etcher) after Francis Barlow, “The Dog and Piece of Flesh,” published by Robert Sayer (London, ca. 1760). (© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.)

Simon Gribelin after Paolo de Mattheis, The Judgment of Hercules, engraving from Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury, Characteristicks of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times.

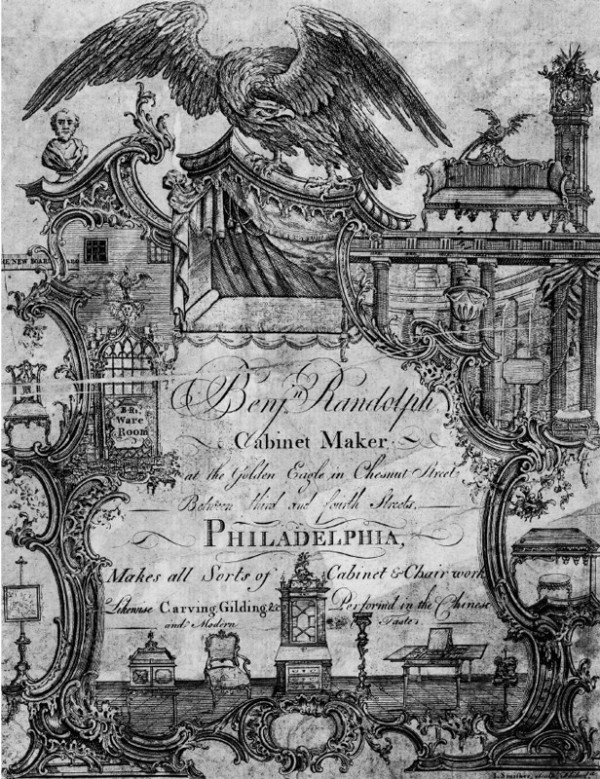

James Smithers, trade card of Benjamin Randolph, 1769. Engraving on paper. 7" x 9". (Courtesy, Library Company of Philadelphia.)

Bracket, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1770. White pine. H. 16", W. 12 3/4", D. 5 3/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Design for a bracket illustrated on plate 27 in Thomas Johnson’s One Hundred & Fifty New Designs (London, 1761). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Easy chair attributed to the shop of Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765-1769. Mahogany with white oak. H. 45 1/4", W. 24 3/8", D. 27 15/16". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details of the carving on the left arm support and right leg of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 44. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the front rail of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 44. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Design for a pier table attributed to Matthias Lock, London, ca. 1745. Graphite on paper. Dimensions not recorded. (© Victoria & Albert Museum.)

Side chair attributed to the shop of Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1769. Mahogany with white cedar. H. 36 3/4", W. 21 3/4" (seat), D. 17 7/8" (seat). (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the back of the side chair illustrated in fig. 48. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair attributed to the shop of Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1769. Mahogany. H. 37 1/2", W. 24 1/2", D. 21". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left rear stile of the side chair illustrated in fig. 50. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the front rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 50. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the side rail of the easy chair illustrated in fig. 44. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the side rail of the pier table illustrated in fig. 55. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pier table attributed to the shop of Benjamin Randolph with carving attributed to John Pollard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1770. Mahogany with yellow pine and walnut. H. 32 3/8", W. 48", D. 23 1/4". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1918 [18.110.27]; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Design for a pier glass and table illustrated on pl. 152 in the third edition of Thomas Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinet Maker’s Director (London, 1762). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Detail of the carving on the front rail of the pier table illustrated in fig. 55.

Detail of the tympanum carving on the high chest illustrated in fig. 14.

Detail of the left truss flanking the fireplace in Cloverfields (fig. 9).

Frieze appliqué over a door in the parlor illustrated in fig. 13.

Firescreen with carving attributed to Hercules Courtenay, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Mahogany. H. 55 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the knee carving on the firescreen illustrated in fig. 61. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tea table with carving attributed to Hercules Courtenay, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Mahogany. H. 27 1/2", Diam. of top: 32 7/8". (Private collection; photo, Christie’s.)

Detail of the knee carving on the tea table illustrated in fig. 63.

Pier table, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Mahogany with yellow pine. H. 32", W. 54", D. 27". (Courtesy, Rhode Island School of Design; bequest of Charles L. Pendleton.)

Detail of the knee carving on the pier table illustrated in fig. 65.

Detail of the leafage in the frieze design illustrated in fig. 22.

Side chair with carving attributed to John Pollard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1769. Mahogany with white cedar and yellow pine. H. 37 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Christie’s.) This example, which has the period ink inscription “Deshler” on its slip-seat frame, is from a set of at least six side chairs, two card tables, and an easy chair.

Card table with carving attributed to John Pollard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1769. Mahogany with oak and yellow pine. H. 28 3/4", W. 33 3/4", D. 16 1/2" (closed). (Private collection; photo, Christie’s.)

Detail of the carving on the back of the side chair illustrated in fig. 68.

Detail of the carving on the right front leg of the card table illustrated in fig. 69.

London carver Thomas Johnson (fig. 1) was one of the most influential rococo designers in the English-speaking world, yet no documented example of his work in wood or in any media other than paper is known. The only carving that can definitively be linked to Johnson or to any tradesman directly associated with him is that of former apprentice and journeyman Hercules Courtenay, who probably went to Philadelphia under an indenture agreement with cabinetmaker Benjamin Randolph. This essay will examine the careers and work of both men and their role in disseminating London rococo design. Johnson’s life is more fully documented than that of Courtenay; the former’s experiences as a carver provide context for understanding the challenges that many émigré artisans like Courtenay faced. At the same time, the furniture and architectural carving associated with Courtenay and the principal tradesman with whom he interacted—John Pollard (and other craftsmen who worked in Randolph’s shop)—suggest that the range of Johnson’s work may have been broader and more diverse than previously thought.[1]

Thomas Johnson

Helena Haywood’s Thomas Johnson and the English Rococo clearly demonstrated that her subject was one of the most influential British proponents of that style, and her subsequent entry in the Dictionary of English Furniture Makers, 1660–1840 included many biographical details about his early life. Much of the latter information proved to be incorrect, largely owing to confusion about which of the many contemporaneous Thomas Johnsons was the carver and designer. Thanks to scholar Jacob Simon’s discovery of Thomas Johnson’s autobiography in the Library and Museum of Freemasonry in London and his article “Thomas Johnson’s The Life of the Author,” a much clearer narrative of the designer’s career has emerged.[2]

Thomas Johnson was born in London in 1723 and apprenticed at the age of thirteen to his cousin Robert Johnson, whom the former described as “the worst carver. . . that had any title to the profession.” In July 1744 Thomas began working as a journeyman for James Whittle, one of the leading carvers and gilders in London. Although Johnson described himself as “an indifferent hand,” his skills improved quickly:

There were upwards of thirty men, amongst which was the famous Matthias Lock, a most excellent carver and reputed to be the best Ornament draughts-man in Europe. To this man I paid great attention, who feeling me emulous, took uncommon pains with me, as did two or three more of the best workmen. I took great delight in copying Lock’s drawings; and now so much was my mind bent to improvement, that I accustomed myself to set up three nights in the week modeling, &c.

Some of Lock’s drawings may have been shop designs, whereas others might have been preparatory work for his first design book, Six Sconces, published just three months before Johnson joined Whittle’s workforce, or for Six Tables, issued in 1746. Lock’s relationship with Johnson was apparently close, as the former interceded when Whittle fired the latter. Johnson described the events in detail:

At this time, Mr. Lock, having a frame to carve for a friend, and not having opportunity to stay from shop, by his desire I undertook to do it for him, but forgetting to bring my mallet from the shop, I made use of a shoemaker’s last. . . . Having finished my job and returned to shop, Mr. Whittle told me to pack up my tools, for he employed no master carvers. . . . Upon hearing [Mr. Lock] . . . immediately went to the shop, and took the frame I had done, with him, and shewed it to Mr. Whittle, telling him at the same time the man had done it was at present out of employ, and would be glad to work for him? Mr. Whittle passed great incomiums on the frame, and asked Mr. Lock, to bring the man who had carved it, to shop, asking what wages the person required; Mr. Lock said twenty shillings per week, was the least. Mr. W. said he would willingly give it, and thought him deserving it. I was sent directly: at my entering the shop, Mr. Lock said to Mr. Whittle, there is the man and that is the frame done with the shoemaker’s last, the frame is sufficient proof of his meriting the wages I have asked for him, and hope you will not go from your word. Mr. Whittle said he would not . . . and his only reason for discharging me, was a precedent to the rest of the men.

Johnson noted that the “great advance from fifteen to twenty shillings per week, doubled my diligence, and fired me with ambition if possible to become as great a man as Lock.” Johnson’s tenure was short-lived; in 1745 he left London after being accused of impregnating the maid of his cousin Robert.[3]

Johnson’s description of his departure is instructive as it shows how few resources some journeymen had when they left their master’s employ and how motivated they were to find work. He and two fellow carvers “let out early” on Easter Sunday morning with “our tools and shirts tied in our leather aprons, the rest of our wardrobes being on our backs, having each procured a hook stick with our bundles on our shoulders . . . all the money we could muster amongst us did not exceed two guineas and a half.” A week later the men arrived in Liverpool, where they came upon ship carver Richard Prescott “at work in a shop; the window had no sash, but open to the street.” After Johnson asked for work and told Prescott about his origin, the latter responded that he had heard of “a new way of working in London.” Johnson “understood he meant contrast, a taste at that time new,” and advised Prescott that he had “worked a good deal in that way” in the “best shop in London.” Prescott made no promise regarding wages but told Johnson, “thou may’st bring thy tools, and thou wilt in the morning . . . ha what thou can earn.” Johnson was not pleased with the arrangement that followed, but it proved advantageous in the long run:

Next morning [Monday] I took my tools and went to shop. . . . [Prescott] said . . . there lies a piece of wood there, thou may’st take it, and do what thou wilt; do something in the tross [bracket] way; if it worth anything I’ll buy it of thee, if its good for nought thou may keep it. . . . the wood he pointed to was a piece of lime-tree, as much as three of us could lift on bench. I sawed off a piece and carved a contrast bracket, to hold a small figure, or busto, &c. . . . I got my job finished by next Saturday noon.

On seeing the bracket (fig. 2), Prescott told Johnson “he had never seen anything that pleased him better,” and paid him a guinea, which, according to the former, was “more than an mon got a day in Lerpoo before.” Unable to offer Johnson any work other than ship carving and concerned over the suitability of his “catstick arms” for that type of work, Prescott offered to help the young man find employment elsewhere. The following day Prescott recommended Johnson to a looking-glass maker named Mr. Roberts and arranged for him to see the latter’s bracket. Roberts, who had previously worked in London for five years, “prais’d” the carving and mentioned having sold a looking-glass frame with a similar dragon. The following morning, he offered Johnson ornaments to carve and gild and took him to see the frame, which was the same one Johnson had carved for Lock. Johnson noted that he “did several jobs for Roberts” and that Prescott provided workspace but “would never take any profit.” Johnson subsequently left Prescott’s shop and went to work for the ship carver’s former apprentice William Mercer. That arrangement proved unsatisfactory because Mercer refused to let Johnson do any ship work.[4]

While in Liverpool, Johnson met artist Edward Alcock, who had greatly admired the contrast bracket the carver made for Prescott. Alcock gave Johnson food, lodging, and a “bench in his ware-house” after he left Mercer’s shop and provided medical assistance when the carver fell ill. After his recovery, Johnson described carving a “very rich table-frame for Mr. Thomas Seal, a merchant, which was much admired, and was the means of my being much esteemed, as a carver, by all the merchants, &c. in town.” Seal and two partners also commissioned Johnson to carve ornaments for their privateer Jenny. That job allowed Johnson to pay his doctor’s bill and other debts and “take a trip across the sea” to Dublin.[5]

In 1747 Johnson moved to Dublin and found employment in the shop of Ireland’s leading carver, John Houghton. Johnson considered Houghton to be the “best wood-carver of basso-relievo figures” he ever saw “before or since” and claimed to have made “great improvements” and “a great deal of money” while working there. Houghton’s shop was noted for the production of sculptural architectural carving in both wood and stone. Among the many works associated with him are a circa 1750 wooden overmantel panel depicting Marcus Aurelius (from Dublin Castle) and a contemporaneous marble chimneypiece with portrait busts commissioned by Thomas Browne, 4th Viscount Kenmare (fig. 3). Johnson’s designs rarely include references to figures from antiquity, but it is likely that he used them, particularly in architectural carving where depictions of “lofty subjects” were popular.[6]

Although Johnson reputedly received “many advantageous offers” during his nine-month stay in Dublin, he returned to Liverpool by early 1748 and set up shop with the financial backing of Alcock, who agreed to loan him money at 5 percent. His autobiography notes that he took three apprentices—two of whom became “eminent carvers in London”—and employed twelve journeymen, carved a “door-case” for merchant ‘T. Ball” (probably Thomas Ball, whose niece Mary Ball married Johnson in 1750), and worked on the new Liverpool Exchange. To allay his debt, Johnson entered into a “disadvantageous partnership” with Alcock, who, the carver claimed, “reduced my number of Journeymen from twelve to two; so that half the earnings of myself and apprentices was his.” Alcock subsequently agreed to dissolve the partnership in exchange for £160, payable over the following year. Ball and his brother Hugh agreed to act as security, and Mr. T. Ball left Johnson £100 “towards the payment” at his death.[7]

In 1753 Johnson returned to Dublin, where he, three of his apprentices, and his four journeymen found employment in the shop of “Mr. Partridge, a principal carver in supplying the glass shops with frames.” Johnson’s autobiography states that he provided “several pieces of work” for Lady Abrella Denny, including a Gothic chimneypiece, and may have later worked for her nephew Lord Shelburne, who tried to entice Johnson to stay in Dublin. According to Johnson, “his Lordship . . . said he understood I was going to England; if that was not my determined resolution, . . . I should have his work and interest; and he would endeavor to get me the custom of almost all the nobility in the kingdom.” Although Johnson replied that it was his “fixt resolution to set off to England,” Shelburne offered him the opportunity to make designs for a “Gothic summer house” he planned to build in England and accompanied the carver and his family and workers on their voyage to London in 1755.[8]

On his return in December, Johnson sought employment from his former master James Whittle:

I went to my old master . . . where my chief dependence was for work. He received me kindly, and gave me some trifling jobs home, which served my boys to do. On my asking him for some better work, he observed that by my being so long from London I must have forgot mostly what I knew when I left. . . . [To convince him otherwise] . . . I carved a girandole, in a taste never before thought on; the principle of it was a ruinated building, with cattle, &c. . . . [fig. 4]. When I had finished it, I carried home the work done by my boys, and on receiving more of the kind, I told Mr. Whittle he had given me nothing worth doing with my own hands, and informed him I had carved a girandole, if he pleased to see it I believed it would convince him there was no work in his shop that I was not capable of doing. I showed him my girandole, which he immediately purchased at a very good price, and bespoke a fellow to it; and so greatly was it esteemed, that many of the men took molds from the heads off the figures.

Johnson may have exaggerated the novelty of his design, as similar works attributed to Matthias Lock are contemporaneous if not earlier (fig. 5); however, it is noteworthy that Johnson offered Whittle a demonstration of his work, just as he had with the “contrast bracket” carved for Prescott a decade earlier.[9]

To further reestablish his reputation in London, Johnson began publishing his designs. This apparently garnered the attention of Thomas Vaills, “a carver, in a very great business,” who, from circa 1756 to 1777, hired Johnson to “make all his drawings, and do the principal part of his work.” Johnson estimated that he received about £150 from Vaills annually. According to Johnson, the patronage of Vaills and Whittle provided enough business to support himself, four apprentices, and twenty-five journeymen. On July 3, 1756, Johnson paid £30 to take Hercules Courtenay as an apprentice, and on March 16, 1760, the carver paid £31.10 for John Fabry. Courtenay’s indenture described Johnson as a carver from St. Giles in the Fields, whereas Fabry’s gave his master’s location as St. Ann’s, Westminster. It is possible that both apprentices had earlier experience, since their indenture fees were above the average for carvers at those dates.[10]

Courtenay’s tenure overlapped with the publication of Johnson’s largest and most well-known collection of designs, A New Book of Ornaments. Initially issued in installments at the rate of four sheets per month between 1756 and 1757, the fifty-three plates constituting the full run appeared as a single collection of designs in 1758 and 1761. The 1761 compilation included one additional plate and was retitled One Hundred & Fifty New Designs. Johnson published two other collections of designs, both from his shop the Golden Boy, which was located on Grafton Street in Soho. The first was composed of eight plates, titled A New Book of Ornaments, priced at 2s., and issued in 1760; the second comprised six plates, titled A New Book of Ornaments By Thos. Johnson Carver, Design’d for Tables & Frizes for Chimneypieces; Useful for Youth to Draw After, priced at 3s., and issued in 1762. No complete copy of the 1760 publication is known, and only one complete copy of the 1762 publication is known. The only other printed works associated with Johnson are the title page for A Book of New Designs for Useful & Ornamental Furniture in Imitation of Drawings By Thos. Johnson Carver, dated June 1, 1775, and an etching with neoclassical looking-glass designs dated the following August. Since Johnson’s autobiography fails to mention the latter book, it is possible that it was never issued as a complete volume. In 1776 he became involved with freemasonry, a pursuit that dominated the later years of his life.[11]

Thomas Johnson’s Designs in Colonial Philadelphia

In “English Furniture Pattern Books in Eighteenth-Century America,” decorative arts scholar Morrison Heckscher lists two colonial references to Johnson’s published work: “Johnsons Carver’s Designs” in the December 19, 1774, inventory of Virginia and Maryland architect and builder William Buckland; and “[A Book of Ornaments] containing 150 new Designs for Carvers” advertised by John M’Lure in the November 18, 1783, issue of the Maryland Journal and Baltimore Advertiser. Few copies of Johnson’s publications appear to have been in colonial America, but several examples of Philadelphia furniture and architectural carving document his influence on the rococo style in that city. As Heckscher observed, the clock in Benjamin Randolph’s trade card (see fig. 41), a wall bracket (see fig. 42), and the drawer appliqués on a Philadelphia high chest and matching dressing table were derived from engravings in One Hundred & Fifty New Designs (figs. 6-8). The same can be said of the carving in Cloverfields (figs. 9-11), a small brick house built on a tract of land William Hemsley patented in Queen Anne’s County, Maryland, on October 10, 1726. Cloverfields passed to his son Philemen (d. 1752), then to Philemen’s brother William, who probably commissioned the carving circa 1770. William’s name appears in the account book of Philadelphia cabinetmaker Benjamin Randolph in 1769, but the entries are not descriptive. The carving in Cloverfields is attributed to Courtenay, and elements of the overmantel appliqué were taken from a design for a mirrored overmantel frame illustrated in plate 5 in Johnson’s One Hundred & Fifty New Designs (figs. 10-12).[12]

No colonial references to either A New Book of Ornaments or A New Book of Ornaments . . . Design’d for Tables & Frizes for Chimneypieces are known, but designs from the latter work did make their way to colonial Philadelphia. Heckscher noted that the border design of the central tablet of a chimneypiece from the Blackwell House in Philadelphia (fig. 13) and the drawer appliqués on a high chest and a matching dressing table in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 14) were taken from plates 3 (figs. 15, 16) and 5 respectively (figs. 17, 18). Architectural carving from the Thomas Ringgold House in Chestertown, Maryland, also features designs from A New Book of Ornaments . . . Design’d for Tables & Frizes for Chimneypieces (fig. 19). The swans on the overmantel tablet are mirror images of those in plate 5 (figs. 18, 20), and the appliqués on either side were inspired by the frieze design in plate 2 (figs. 21, 22). Like William Hemsley, Ringgold had an account with Benjamin Randolph. Although the August 5, 1771, debit entry under Ringgold’s name—“To Shop 23:6:6d”—would have been insufficient for all the appliqués, trusses, and garlands installed in his parlor, the Maryland merchant’s patronage of Randolph and the cabinetmaker’s association with Courtenay’s and Johnson’s designs give cause for speculation that the basic architectural components could have been fabricated in the cabinetmaker’s shop before being delivered to the carver (or carvers if there were time constraints).[13]

The frieze appliqués on the Blackwell House chimneypiece bear a strong resemblance to Johnson’s work (fig. 13). The right appliqué depicts a fox stealing a fowl, imagery occurring at the bottom of a looking-glass design illustrated in plate 43 in the collected edition of One Hundred & Fifty New Designs (figs. 23, 24). Johnson’s source was the title page of Animals of Various Species Accurately Drawn by Francis Barlow, part three of Various Birds and Beasts Drawn from the Life (London, ca. 1660–1670)—a publication from which he borrowed heavily (fig. 25). The dog and stag on the left appliqué and the bull and dog on the central tablet can also be traced to engravings in that publication (figs. 26-29). These Barlow-based images, and possibly a variant of the border framing the fox and fowl and dog and stag, may have been published in Johnson’s 1760 New Book. It is also possible that copies of Johnson’s drawings done in preparation for the aforementioned publications, but not included in either, made their way to Philadelphia.[14]

Design books were only one avenue for the transfer of London rococo designs. Émigré carvers like Courtenay and John Pollard probably arrived with portfolios of engravings and drawings, which they would have begun compiling during their apprenticeships. The scrapbook of London carver Gideon Saint is a particularly relevant example, because he established a shop near Thomas Johnson’s the year before the latter declared bankruptcy and Courtenay immigrated to Philadelphia. Saint’s scrapbook consists of drawings and engravings—primarily those of Matthias Lock, Lock and Copland, and Johnson—pasted into the book and drawings executed directly on the pages (figs. 30, 31). Some of the drawings are copies of published designs, whereas others—two of which are initialed “G. S.”—probably represent Saint’s work and possibly those of his former master Jacob Touzey. If Courtenay had a similar collection, it likely included copies and engravings of Johnson’s designs as well as conceptual and working drawings executed during his tenure in the latter’s shop. The presence of such a portfolio in Randolph’s shop would explain the use of relatively obscure Johnson designs by other carvers, including John Pollard, to whom the Blackwell House tablet and appliqués are attributed.[15]

Johnson’s interaction with Matthias Lock suggests how this sharing of information might have occurred. During his term in Whittle’s shop, Johnson copied Lock’s drawings and practiced modeling in the evenings. Assuming that Courtenay and Pollard arrived with portfolios of designs, they may have shared them with each other as well as with Randolph and the journeymen and apprentices in his shop. Copying designs and perfecting drawing skills were among the first steps required to become a carver. Robert Campbell’s The London Tradesman (1747) noted that a “Carver . . . ought to be set to Drawing, and Kept at it as long as his Apprenticeship lasts.” Designers like Lock and Johnson clearly encouraged that practice. Lock published a drawing primer titled The Principles of Ornament or the Youth’s Guide to Drawing of Foliage (ca. 1746; reissued by Robert Sayer, ca. 1768) (fig. 32), and Johnson began referring to himself as a “Drawing Master” by 1760 (fig. 33). Both men probably spent as much time at the drawing table as at the carving bench, which would not have gone unnoticed by apprentices and journeymen like Courtenay who sought to imitate their masters. Just as Johnson claimed to have done “all [the] . . . drawing] and a “principal part of [the] . . . work” for Thomas Vaills, furniture and architectural carving associated with Benjamin Randolph’s shop suggests that Courtenay was responsible for a great deal of the Philadelphia cabinetmaker’s ornamental design, at least from the mid- to late-1760s.[16]

Hercules Courtenay

The earliest reference to Courtenay is his signature on the Non-importation Agreement of 1765. Courtenay probably completed his apprenticeship by 1763 and may have worked as a journeyman in Johnson’s shop until 1764, when the designer declared bankruptcy after suffering cost overruns in building a new house and ship following his family’s move from Seven Dials to Soho. Courtenay may have received passage to Philadelphia as part of an indenture agreement with Benjamin Randolph. In December 1766 Randolph paid £3.16.6 to the carver’s account with Jacob Chrystler, and the following July he bought Courtenay a “barygane coate.” If Courtenay was indentured, his term likely expired by May 1768, when he married Mary Shute at Gloria Dei Church. Three months later he advertised, “Hercules Courtenay, Carver and Gilder, from London . . . undertakes all Manner of CARVING and GILDING, in the newest Taste, at his House in Front-Street, between Chestnut and Walnut on Front Street.”[17]

Randolph’s account and receipt books do not specify the work Courtenay did as a member of the cabinetmaker’s workforce, but several bills for architectural work survive from the period when the carver operated his own shop. The earliest work that can be documented to Courtenay is on a chimneypiece from the parlor of Samuel Powel’s house at 224 South Third Street (fig. 34). Between August and October 1770, Powel paid Courtenay £60 for carving in his “dwelling house.” The trusses on the chimneypiece have acanthus leaves that stand in high relief on “toed-back” moldings. Typical of rococo carving, the leaves display considerable overlapping as well as twisting and turning at the ends. On the large leaves, Courtenay used chip cuts and short parallel gouge cuts to articulate the convex surfaces behind the turned ends (fig. 35). This technique frequently occurs on furniture carving attributed to him (figs. 36, 37).[18]

The central tablet of the Powel chimneypiece depicts Aesop’s fable “The Dog and Its Reflection” (also “The Dog and Piece of Flesh” and “The Dog and Shadow”) (fig. 38). Courtenay’s design may have been derived from an illustration in Francis Barlow’s edition, published in 1687, but similar engravings by others—Wencelaus Hollar, Elisha Kirkhill, and Robert Sayer—were available at the time (fig. 39). Thomas Johnson frequently borrowed designs from Barlow’s engravings, so it is only natural that Courtenay would have done the same. A simplified version of “The Dog and Its Reflection” also appears on the end plate pattern of a ten-plate stove marked “W. H. STEIGEL / ELIZABETH FURNACE” and dated 1769. Like many of his competitors, Courtenay carved casting patterns for regional iron furnaces.[19]

As an independent craftsman, Courtenay enjoyed the patronage of several prominent Philadelphians, including John Cadwalader and John Dickinson. On September 17, 1770, the carver charged Cadwalader £81.2.11 for “27 Books of Gold laid on Cornice” and a variety of moldings, appliqués, friezes, trusses, and tablets. One tablet, described as “The Judgment of Hercul.” cost £8.10 (fig. 40), which was more than the Philadelphia firm Bernard and Jugiez charged for carving the highly sculptural mahogany pattern that ironmaster Isaac Zane Jr. used to cast firebacks with the “Arms of Earl of Fairfax.” This suggests that the “tablet” was quite large and may have been an overmantel relief similar to those produced by John Houghton. Johnson probably carved bas-relief figures and panels while working in Houghton’s shop, and it is likely that he taught Courtenay and other apprentices to do the same. Courtenay was clearly capable of doing a variety of sculptural work, as indicated by his April 1773 bill of £2.5 for carving six busts for Cadwalader’s coach. Dickinson’s account with Courtenay was even larger than Cadwalader’s. On November 1, 1772, Dickinson paid the carver £105.7.6 for carving 50 trusses, 23 stair brackets, “2 Long Brackets for West Room” (probably large trusses for the sides of a chimneypiece architrave), 59 feet 2 inches of molding, four flowers (probably for the ears of an overmantel architrave), and a spandrel “for [the] Stucco man.”[20]

Courtenay worked in the carving trade until he enlisted in the colonial army during the Revolutionary War. He was accused of “leaving his howitzer in the field in the action of Brandywine, in a cowardly unofficerlike manner” but received only a “reprimand in consideration of his service and previous bravery.” Courtenay abandoned his trade and became a tavern keeper in 1779. He continued in that business until his death in October 1784.[21]

Carving and Collaboration in Benjamin Randolph’s Shop

Courtenay may have been the principal conduit for Thomas Johnson’s designs in Philadelphia. Entries in Benjamin Randolph’s receipt book (1763–1777) and account book (1768–1777) suggest that he and John Pollard were the cabinetmaker’s principal carvers during the 1760s and 1770s. Pollard’s background is unknown, but the furniture and architectural carving attributed to him suggest that he trained in a major London carving shop, perhaps that of Johnson. The designer’s bankruptcy undoubtedly left his apprentices in search of new masters and his journeymen in pursuit of employment. Randolph and his wife, Anna, had inherited a large sum of money from her father the year before, so the cabinetmaker was in an ideal position to begin building his workforce. In 1767 he purchased the Chestnut Street shop of Quaker carpenter Thomas Shoemaker and began advertising cabinet and chair work at the “Sign of the Golden Eagle.” His trade card, engraved by James Smithers in 1769, includes designs by Thomas Johnson and Thomas Chippendale—images that asserted his shop’s ability to work in the latest London taste (fig. 41).[22]

Just as Johnson carved a “contrast bracket” for Robert Prescott and a girandole for James Whittle, Courtenay and Pollard may have each produced an example of avant-garde work for Randolph to demonstrate their skill and knowledge of rococo design. If so, they may have carved a bracket, looking-glass frame, or other furniture form that required minimal joinery. The bracket illustrated in figure 42 was based on plate 27 in Johnson’s One Hundred & Fifty New Designs (fig. 43), and its carving relates to work attributed to both Courtenay and Pollard. Differentiating between the two hands can sometimes be challenging, because of Courtenay’s and Pollard’s contemporaneous London training and their influence on each other while working in Randolph’s shop. This is particularly true in the case of heavily painted architectural carving or castings (from carved patterns), where the technical nuances of their work are less clear.[23]

With Courtenay and Pollard as part of his workforce, Randolph was able to offer his clients an extraordinary range of carved furniture forms. This is illustrated by a group of chairs likely made in his shop between 1765 and 1770, some of which descended in the family of the cabinetmaker’s second wife, Mary Wilkinson Fenimore (figs. 44-46). These chairs have been the subject of considerable debate since the 1920s, when scholars James Curran and Samuel Woodhouse began referring to certain examples as “sample chairs,” theorizing that they were kept as prototypes in Randolph’s shop. Subsequent scholars have refuted that theory, but as decorative arts scholar Andrew Brunk observed, these chairs are “unique among known Philadelphia examples.”[24]

With its exposed, carved arm faces, carved rails, and cabriole legs with hairy paw feet at the front and rear, the easy chair illustrated in figures 44–46 represents a clear departure from contemporaneous Philadelphia work. The arms are the most overtly rococo features of the chair, with sweeping curves, disappearing planes, and elaborately decorated inner and outer faces (fig. 45). The carving relates to work associated with both Courtenay and Pollard, and, like the architectural ornaments in the Blackwell House, may have involved both hands. If that is the case, the chair probably dates 1765–1769, when Courtenay and Pollard were both journeymen in Randolph’s shop. The front feet are the most highly developed American examples of their type, having well-defined pads, deeply modeled and shaded strands of hair, and long fetlocks with large tufts that curl and intertwine in a naturalistic manner (fig. 45). By extending the toe tendons up into each ankle, the carver created a sense of tension that makes his feet appear almost life-like. Paw feet and masks are absent from Johnson’s published designs, but those details occur on circa 1745 drawings of sideboard tables attributed to his mentor Matthias Lock (fig. 47) and remained popular in English furniture through the 1750s. Paw feet and masks are also archetypal in mid-eighteenth-century furniture from Ireland, where Thomas Johnson worked between 1747 and 1748 and again between 1753 and 1755. If Johnson assimilated Irish details and passed his knowledge of them to his apprentices, Courtenay is a likely source for their appearance in furniture from Randolph’s shop. Courtenay may even have been of Irish descent, as was a contemporaneous Baltimore merchant with the same name.

Circumstantial evidence suggests that a set of commode-seat side chairs commissioned by Philadelphia merchant John Cadwalader are also from Randolph’s shop (fig. 48). Seven examples from the set are known, but there may have been between sixteen and twenty originally. They appear to have been completed before September 1, 1770, when Charles Willson Peale received payment in full for portraits of John Cadwalader’s parents and brother Lambert, the latter of which depicts a chair from the set. During the fall of 1769, Lambert supervised work on John and Elizabeth’s town house while the couple attended to her ailing father in Maryland. John’s Waste Book notes that he reimbursed his brother £94.15 for “B. Randolph[s] acct for Furniture” and £30 for “2 marble Slabs etc. had of C. Coxe.” It is impossible to attribute the chairs to Randolph’s shop based solely on the £94.15 entry, but that sum would have been sufficient for a large set.[25]

The chair illustrated in figure 48 may be the one depicted in Lambert’s portrait. The underside of the shoe is numbered “I,” and the carving is more detailed and more carefully rendered than that on the other surviving chairs. Courtenay’s involvement in the production of the chairs is evident in the ornament on the back; the leaves on the stiles are flatter versions of those on the trusses of the Powel House and knees of the card table in figure 36, but they have the same turns at the end and chip cuts on the trailing convex surfaces (fig. 49). If he did not actually carve the backs of the chairs, Courtenay was almost certainly the draftsman responsible for the design of their leafage. In the production of large, ornate sets or suites, he or Pollard would likely have drawn the ornament, overseen the production of patterns, and, possibly, produced a prototype to guide other carvers in Randolph’s workforce. The cabinetmaker clearly employed other carvers, including, quite possibly, Pollard’s future partner Richard Butts, who is first mentioned in Randolph’s account book in 1768. Evidence of this is the rail and knee leafage on the Cadwalader chairs, which is by an artisan somewhat less skilled than the carver of the chair backs. In the production of large sets or elaborately carved forms, the most talented craftsmen typically carved the ornaments that were the closest to the observer’s eye.[26]

A side chair with similarly carved stiles (figs. 50, 51) appears to be contemporaneous with the Cadwalader commode-seat set but, like most of the seating furniture illustrated on Randolph’s trade card (fig. 41), it has scroll feet. That type of foot was the most popular rococo variant during the period when Courtenay and Pollard served their apprenticeships and worked as journeymen in London. All of the side-chair designs in the first and second editions of Thomas Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754, 1755) incorporate scroll feet, as do most of those in the third edition (1762). The carving on this Philadelphia example relates to work associated with both Courtenay and Pollard, but it may be by a journeyman working from the émigrés’ designs and/or under their supervision. This theory is supported by comparisons of similar motifs, such as the cabochon and acanthus clusters on the front rail of the side chair (fig. 52), side rails of the easy chair (fig. 53), and side rails of a pier table corresponding to Cadwalader’s Waste Book entry for “2 marble slabs etc. had of C. Coxe” (figs. 54, 55). Although the table was inspired by “A Pier Glass & Table” design in plate 152 in the third edition of the Director (fig. 56) and has carving attributed to Pollard, passages of the ornament resemble Courtenay’s work, at least from a drawing perspective. This is most evident in the tripartite cabochons flanking the reclining figure on the front rail and the twisting and turning leafage on either side (fig. 57).[27]

Philadelphia Carving in the London Style

Courtenay’s career as an independent artisan began by August 1769 and continued until 1779. Pollard worked for Randolph until 1773, when he and an artisan by the last name of Butts (presumably Richard Butts) advertised “all manner of Carving in the House, Cabinet, Coach, and Ship way” at the “sign of the CHINESE SHIELD.” The last entry for Pollard in Randolph’s account book is 1779, but several objects associated with the carver suggest that he worked into the 1780s. Although Pollard and Courtenay were competitors, they almost certainly worked together on occasion. Bills for architectural carving installed in John and Elizabeth Cadwalader’s town house suggest that Randolph may have facilitated some of Courtenay’s and Pollard’s collaborations. On November 24, 1770, the cabinetmaker billed Cadwalader £252.16.1 for carving in his large front and back parlors, entry, small parlor, and second-storey front and back rooms. This work—comprising a variety of moldings, trusses, and friezes along with “two dragons for the pediments”—was done when Pollard was Randolph’s principal carver. Courtenay’s bill, which totaled £81.2.11, included carving for the same rooms, so it is likely that he and Pollard produced some working drawings and patterns together, to achieve a harmonious decorative scheme. Work by both men is present in the parlor from the Blackwell House, although that carving probably dates from the period when they were both in Randolph’s shop.[28]

In addition to influencing each other’s work, Courtenay and Pollard had to accommodate prevailing tastes in Philadelphia, where furniture forms and details that would have been considered old-fashioned in London– cabriole-leg high chests and dressing tables, claw-and-ball and hairy feet—remained popular during the 1760s and 1770s. Although both carvers continued quoting published designs, most of their work was in a hybridized Philadelphia-London style. A high chest (fig. 14) and matching dressing table serve as a case in point. Courtenay based their drawer appliqués on a tablet design in A New Book of Ornaments or A New Book of Ornament . . . Design’d for Tables & Frizes for Chimneypieces but changed the orientation of the birds (figs. 17, 18). The looping strapwork and complex layering of the leafage resembles those features in several Johnson designs but do not relate directly to any of them. Like the arm faces of the easy chair illustrated in figure 44, the tympanum carving and foliate scrolls on the high chest are preeminent examples of Courtenay’s work (fig. 58). The leaves that descend from the upper edge of the scroll moldings where the ogee-and-cove transitions into a deep cove are set in high relief, recalling those on the trusses flanking the fireplace opening in the parlor of Cloverfields (fig. 59) as well as those from the Powel House (fig. 35).[29]

Other examples of Courtenay’s work relate very closely to the tympanum carving on the high chest. The frieze appliqués over the doors in the Blackwell parlor are, in many respects, elongated inversions of the same design (albeit without having a loop in the strapwork) (fig. 60), whereas the knee carving on the firescreen illustrated in figures 61 and 62 represents a greatly simplified variant. Courtenay’s designs often feature similar arrangements of leaves; small, stacked C-scrolls; and tripartite cabochon-like devices. He was equally adept at working in high relief or creating the illusion of considerable depth on furniture and architectural components that did not require such sculptural treatment. Courtenay’s proficiency in the latter is evident in the knee carving on a variety of furniture forms, including the tea table illustrated in figures 63 and 64. Like the high chest, the table is a traditional Philadelphia form, having a compressed ball surmounted by a fluted Doric column and claw-and-ball feet. Courtenay’s feet are among the most robust from eighteenth-century Philadelphia, having deeply modeled tendons and prominent knuckles articulated with fine lines at each joint.

The merging of Philadelphia and London styles is epitomized by a suite of furniture—six side chairs, two card tables, and one easy chair—that descended in the family of Germantown merchant David Deshler (figs. 68, 69). All of the objects have cabriole legs and claw-and-ball feet that resemble contemporaneous and earlier Philadelphia work more than London rococo furniture. In contrast, the carving is fully in the London style, rendered in high relief, and strategically placed to emphasize the flow of each component. The latter is most evident in the leafage on the crest (fig. 70), splat, and legs of the chairs and rails and legs (fig. 71) of the tables. As decorative arts scholar Martha Willoughby has observed, several of the carved details appear to have been inspired by ornaments on a ceiling design illustrated on plate 11 in Johnson’s Hundred & Fifty New Designs. Her research also suggests that David Deshler commissioned the suite around the time of his daughter Esther’s marriage to merchant John Morton on September 29, 1769. If so, that would have been when Pollard assumed the role of Randolph’s principal carver after Courtenay left to establish his own shop.

The documentary information and carving presented in this essay indicate that design books, portfolios of drawings and engravings compiled by émigré craftsmen, and individual craftsmen like Hercules Courtenay and John Pollard were responsible for the transfer of London rococo style to Philadelphia, where there was a demand for the latest English furniture designs as well as for conservative forms decorated with “modern” ornament. The work associated with Courtenay also prompts speculation about Thomas Johnson and the probable appearance of the designer’s carving. Given the former’s training, it is logical to assume that his work resembled that of his master. This supposition is supported by comparisons of Courtenay’s carving and corresponding details shown in engravings by his master. As the leafage carved on the knees of the pier table and illustrated on the frieze design in plate 2 in A New Book of Ornaments . . . Design’d for Tables & Frizes for Chimneypieces reveals, Courtenay’s and Johnson’s carving styles—the latter’s echoed in his drawing—were closely aligned (figs. 65–67), as were, presumably, those of other Johnson apprentices. This should be borne in mind by furniture historians when considering furniture and architectural carving suspected of having been done in Johnson’s shop. The furniture associated with Courtenay also indicates that scholars should look beyond objects that resemble Johnson’s published designs in considering the latter’s work. As Johnson wrote in 1758, “Tis a duty incumbent on an Author to endeavor at pleasing every Taste.”[30]

For more on Courtenay, Pollard, and Randolph, see Luke Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part III: Hercules Courtenay and His School,” Antiques 131, no. 5 (May 1987): 1044–64; Luke Beckerdite and Leroy Graves, “New Insights on John Cadwalader’s Commode-Seat Side Chairs,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2000), pp. 152–68; and Andrew Brunk, “Benjamin Randolph Revisited,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), pp. 5–82.

Helena Hayward, Thomas Johnson and the English Rococo (London: Alec Tiranti, 1964); entry for Thomas Johnson in Dictionary of English Furniture Makers, 1660–1840, edited by Geoffrey Beard and Christopher Gilbert (Leeds, Eng.: W. S. Manney and Son for the Furniture History Society, 1986), pp. 491–92. Jacob Simon, “Thomas Johnson’s The Life of the Author,” Furniture History 39 (2003): 1-64. The title page for Johnson’s autobiography reads: “No. VI. An Appendix to Summer Productions; or, Progressive Miscellanies: Being the Life of the Author, Written by himself, and Illustrated with applicable Quotations from Blackmore, Cowley, Dryden, Milton, Otway, Shakespeare and others. And Embellished With Copper-plates suitable to the several Subjects.” The book was printed for Johnson in 1793, and a copy is in the collection of the Library and Museum of Freemasonry in London. All of the citations in this article are from that copy, which furniture scholar Martha Willoughby photographed for the author.

Simon, “Thomas Johnson’s The Life of the Author,” pp. 2–4. Thomas Johnson, Life of the Author, pp. 5, 8, 14–21.

Simon, “Thomas Johnson’s The Life of the Author,” p. 5. Johnson, Life of the Author, pp. 23–29.

Simon, “Thomas Johnson’s The Life of the Author,” p. 5. Johnson, Life of the Author, pp. 30–31: “[Mr. Seal] asked me, if I could carve a lion, for her head / I told him, I had not the least doubt of it. He being a very high party man, the ship was called the Jenny, (after Miss Jenny Cameron.)—There was a figure of Miss Jenny, with a white rose in her breast; and a great deal of ornament in her stern. This job was agreed on, and finished to the owner’s satisfaction.”

Simon, “Thomas Johnson’s The Life of the Author,” p. 6. Johnson, Life of the Author, pp. 32–33.

Simon, “Thomas Johnson’s The Life of the Author,” p. 6. Johnson, Life of the Author, pp. 33–42.

Simon, “Thomas Johnson’s The Life of the Author,” pp. 6–7. Johnson, Life of the Author, pp. 42–44.

Simon, “Thomas Johnson’s The Life of the Author,” pp. 7–8. Johnson, Life of the Author, pp. 45–47: Whittle clearly had a high regard for Johnson’s work, since he hired him to produce a “frame bespoke for his Royal Highness the Prince of Wales.” Johnson “made the model, and executed the principal; which frame, when done, came to £240.” Johnson’s autobiography notes that the frame was destroyed in a fire that consumed the house of Whittle’s son-in-law and partner Samuel Norman. Johnson worked for Norman for years after Whittle’s death, but Norman violated the terms of their agreement and the relationship ended.

Simon, “Thomas Johnson’s The Life of the Author,” p. 10. Johnson, Life of the Author, p. 46: Johnson notes that he had initially taken “a small house in Queen-Street, near the Seven Dials,” but it proved too small. Whittle’s and Viall’s patronage enabled him to move to a larger house on Grafton Street, St. Ann’s, Soho.

For the dates, number of plates, issuing specifications, and prices of Johnson’s published work, see Simon, “Thomas Johnson’s The Life of the Author,” pp. 19–20. For more on A New Book of Ornaments By Thos. Johnson Carver, Design’d for Tables & Frizes for Chimneypieces; Useful for Youth to Draw After, see Helena Hayward, “Newly Discovered Designs by Thomas Johnson,” Furniture History 11 (1975): 40–47; and Morrison H. Heckscher, “English Furniture Pattern Books in Eighteenth-Century America,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1994), p. 192.

Heckscher, “English Furniture Pattern Books,” pp. 191–92. For Cloverfields, see Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part III,” pp. 1052–55.

Heckscher, “English Furniture Pattern Books,” p. 192. Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part III,” pp. 1052–53, 1056–57; Luke Beckerdite, “Pattern Carving in Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2014), pp. 120–22.

For the looking-glass design, see Elizabeth White, Pictorial Dictionary of British 18th Century Furniture Design: The Printed Sources (Woodbridge, Suffolk, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1990), p. 333 (lower right). Beckerdite, “Pattern Carving,” p. 124.

Morrison H. Heckscher, “Gideon Saint: An Eighteenth-Century Carver and His Scrapbook,” Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art 27 (February 1969): 299–311.

Robert Campbell, The London Tradesman (1747; reprinted, Newton Abbot; Eng.: David & Charles Reprints, 1969). Simon, “Thomas Johnson’s The Life of the Author,” pp. 7, 12.

See Beatrice Garvan’s entry for Courtenay in Philadelphia: Three Centuries of American Art (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1976), p. 111; Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part III,” pp. 1045–56. Pennsylvania Gazette, August 14, 1769

Samuel Powel Ledger, 1760–1793, p. 129, Historical Society of Pennsylvania (hereafter HSP), Philadelphia; Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part III,” p. 1048; Brunk, “Benjamin Randolph Revisited,” p. 6.

Richard H. Randall Jr., “Designs for Philadelphia Carvers,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1996), pp. 57–62. Beckerdite, “Pattern Carving,” pp. 116–17.

Incoming Correspondence, Bills, and Receipts, 1770, box 2, folder 17, General John Cadwalader section, Cadwalader Papers, HSP (hereafter CJCS). Courtenay’s bill to Cadwalader is reproduced in Nicholas B. Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur in Philadelphia: The House and Furniture of General John Cadwalader (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1964), p. 12. See also Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part III,” p. 1051. For more on the Fairfax chimney back and Bernard and Jugiez, see Luke Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part II: Bernard and Jugiez,” Antiques 128, no. 3 (September 1985): 498–509; and Luke Beckerdite and Alan Miller, “A Table’s Tale: Craft, Art, and Opportunity in Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 2–45. Logan Papers, vol. 30, pp. 63–64, HSP. Courtenay’s bill to Dickinson is reproduced in Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, p. 143.

Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 41 (1917): 202. Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part III,” p. 1063.

Brunk, “Benjamin Randolph Revisited,” pp. 6, 18, 76, 79.

Simon, “Thomas Johnson’s The Life of the Author,” p. 5.

Brunk, “Benjamin Randolph Revisited,” pp. 29–36. Like Courtenay, Pollard may have been indentured to Randolph. Entries in the cabinetmaker’s account book record rent payments made for Pollard on December 7, 1765 and July 22, 1766.

John Cadwalader Waste Book, box 8, GJCS p. 53. The payment to Peale was for “2 minature & 3 portrait Paintings in full.” For more on the sitters, see Wainwright, Colonial Grandeu, pp. 108–11, 114–15. Some scholars have argued that the chair in Lambert’s portrait is from a different set because it has plain stiles; however, evidence suggests otherwise. Peale’s portrait of the John Cadwalader family depicts one of the commode-front tables owned by Cadwalader. The table and chair in the paintings show similar degrees of artistic license when compared with the actual objects. Beckerdite and Graves, “New Insights on John Cadwalader’s Commode-Seat Side Chairs.” John Cadwalader Waste Book, 1769–1771, box 8, p. 63, CJCS.

Brunk, “Benjamin Randolph Revisited,” p. 76. For the earliest advertisement by Pollard and Butts, see Pennsylvania Gazette, February 22, 1773. Plates 1–5 in Matthias Lock, The Principles of Ornament, or the Youth’s Guide to Drawing of Foliage (1769) illustrate the principle of placing more complex designs closer to the eye. Similarly, Thomas Sheraton’s Cabinet Dictionary (1803) states:

Figures, foliage, and flowers are the three great subjects of carving; which, in the finishing, require a strength of delicacy suited to the height or distance of the object from the eye. . . . It requires some command of the mind, for the carver to work so close as to suit considerable height or distance; in which case, his eye, in working at so short a distance, must not govern him. . . but his judgement must take the lead, and constantly suggest to him the folly of finishing, in a tender manner, those flowers, and foliage. . . which are only to be viewed at a distance.

Cadwalader Waste Book, p. 63.

Pennsylvania Gazette, February 22, 1773. Brunk, “Benjamin Randolph Revisited,” pp. 55, 79. Randolph’s bill for architectural carving is transcribed in Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, p. 21. Incoming Correspondence, Bills, and Receipts, 1770, box 2, GJCS. Courtenay’s bill is reproduced in Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur, p. 12

Heckscher, “English Furniture Pattern Books,” p. 192.

Simon, “Thomas Johnson’s The Life of the Author,” p. 11.