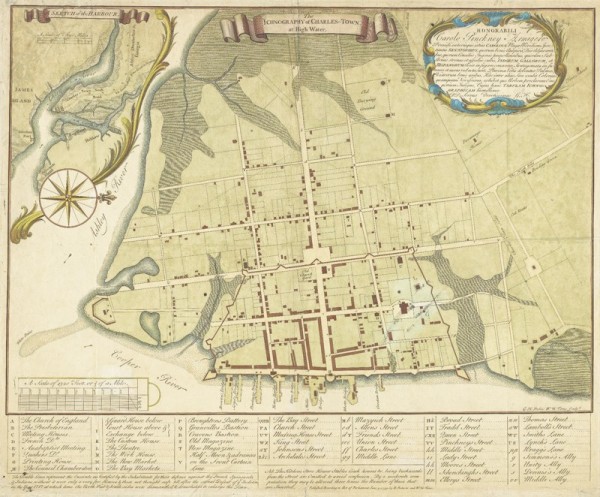

B. Roberts and William Henry Toms, Ichnography of Charles-Town at High Water, London, England, 1739. 13 x 18 3/8". (Courtesy, Brown University.) The map shows the outline of the walled city and growth beyond those fortifications.

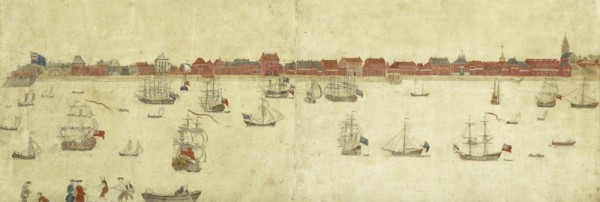

Bishop Roberts, Prospect of Charles Town, watercolor and ink on paper, Charleston, South Carolina, 1737–1738. 18 1/2 x 46 1/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) A fire in 1740 destroyed many of the buildings shown in this view.

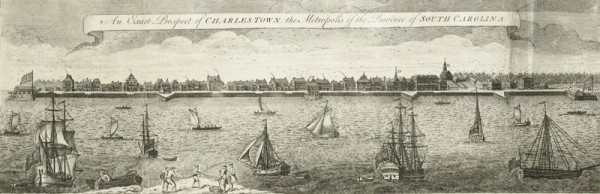

Bishop Roberts (painter) and William Henry Toms (engraver), An Exact Prospect of Charlestown, the Metropolis of the Province of South Carolina, London, England, 1739. 10 1/4 x 23 5/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) This engraving was based on Roberts’s watercolor illustrated in fig. 2.

John William Hill, Panorama of Charleston, 1851. Hand-tinted lithograph on paper. 24 x 41 1/2". (Courtesy, Gibbes Museum of Art / Carolina Art Association.)

Bowl fragments, Barbados, ca. 1800. Green lead-glazed earthenware. (Codrington Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These were recovered from excavations at Codrington College, St. John, Barbados.

Bowls, Barbados, twentieth century. Unglazed earthenware. D. 6 3/4". (Courtesy, Michael Stoner; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The bowl in front is typical of the modern form of Barbados redware (not of Barbadian clay) that was made for the Barbados tourism industry by Chalky Mount Pottery ca. 1990. The bowl in back is a modern reproduction of a 1690–1700 bowl excavated at Codrington College, St. John, Barbados.

Sarah Stroud Clarke, Drayton Hall Archaeologist and Curator of Collections, excavating a ditch feature that predates the ca. 1750 Drayton Hall. (Courtesy, Drayton Hall Preservation Trust.)

Teapot fragments, attributed to Pieter Adriaensz Kocks, The “Greek A” Factory, Delft, Netherlands, 1705–1720. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Drayton Hall, National Trust for Historic Preservation.)

Teapot, Pieter Adriaensz Kocks, The “Greek A” Factory, Delft, Netherlands, 1705–1720. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 4 3/4". (Courtesy, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.) This rare black delft, which was made for a short period at the beginning of the eighteenth century, was intended to mimic Chinese lacquer.

Building façade of the Planter’s Hotel, Charleston, South Carolina, 1920s. (Collections of The Charleston Museum.) This photo was taken before 1936, when the hotel was converted to a theater on the site of the original 1736 Dock Street Theatre.

Portion of the Dock Street Theatre privy revealed in an elevator shaft. (Courtesy, The Charleston Museum; photo, Martha Zierden.)

Teabowl, Fukien (Fujian) province, China, 1750s. Porcelain. D. 2 15/16". (Collections of The Charleston Museum; photo, Sean Money.)

Jar and bowl, Charleston area, South Carolina, eighteenth century. Low-fired earthenware. H. of jar 6", D. of bowl 11 1/16". (Courtesy, The Charleston Museum; photo, Sean Money.) Typical vessel forms for colonoware are globular jars and open bowls. These vessels were found at the Meeting Street Office site and Heyward-Washington House, respectively.

Colonoware plate fragments, Charleston area, South Carolina, eighteenth century. Low-fired earthenware. D. 7 5/8". (Courtesy, The Charleston Museum; photo, Sean Money.) These unusual colonoware plates are from the Meeting Street Office site (left) and Heyward-Washington House (right). The rim of the vessel on the left features painted black dots reminiscent of delftware; the vessel on the right is impressed with the edge of a cockleshell or unknown tool.

Teapot fragments, John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, The Charleston Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Note the incorporation of the molded Barleycorn design on the panels of the vessel.

Teabowl fragment, John Bartlam, Cain Hoy, South Carolina, 1765–1770. Soft-paste porcelain. Extrapolated h. of bowl 3 15/16". (The Charleston Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Teapots, Yixing, China, (left) ca. 1825; (right) ca. 1750. Unglazed stoneware. H. of left example 3 3/4". (Courtesy, The Charleston Museum; photo, Sean Money.) The fragmentary teapot illustrated on the right was recovered from the ca. 1770 privy fill at the South Carolina Society Hall, Meeting Street.

Pièrre Eugene du Simitiere (b. Pierre-Eugène du Cimetière, 1736–1784), Drayton Hall S.C., dated 1765 on reverse. Watercolor on paper. 8 3/8" x 12 1/2". (Courtesy, J. Lockard Collection; photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and Craig McDougal.) The watercolor depicts the original design and eighteenth-century appearance of Drayton Hall, North America’s earliest example of fully executed Palladian architecture.

Teapot with archaeologically recovered fragments, probably Staffordshire, England, 1765–1770. Unglazed stoneware. H. 4 7/16". (Courtesy, Drayton Hall Preservation Trust and Drayton Hall, National Trust for Historic Preservation.) Modeled after a Chinese Yixing example, this is the only known example of this type of English dry-bodied stoneware found in an American archaeological context.

Punch bowls. (Left) England, ca. 1760. Tin-glazed earthenware. Inscribed: “Success to Trade”. (Right) China, ca. 1760. Chinese export porcelain. D. 11". (Collections of The Charleston Museum; photo, Sean Money.)

Heyward-Washington House, Charleston, South Carolina, ca. 1772. (Photo, Sean Money.) The brick double house built by Thomas Heyward in 1772 was at least the third home on the Church Street site. Excavations by Elaine Herold in 1975–1977 and Martha Zierden in 2002 revealed structures and deposits spanning the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The property is a historic house museum owned by The Charleston Museum.

Earthenwares, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1760–1780. Slip-trailed wares, clouded wares, and lead-glazed earthenware. D. of center dish 9 5/16". (Collections of The Charleston Museum; photo, Sean Money.) The objects in this group were recovered in Charleston, South Carolina.

Pipkin or sauce pot, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1760–1780. Lead-glazed earthenware. L. including handle 9 5/16". (Collections of The Charleston Museum; photo, Sean Money.)

Children’s cups, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, England, 1810–1830. Pearlware, creamware, and whitewares. H. 2 5/8". (Collections of The Charleston Museum; photo, Sean Money.) These cups were archaeologically recovered from Charleston Place, Heyward-Washington House, and the Meeting Street Office site.

Children’s cup, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, England, 1810–1830. Pearlware, D. 2 5/8". Inscribed: “A PRESENT FOR WILLIAM” (Collections of The Charleston Museum; photo by Sean Money.)

The city of Charleston has a complex history that is reflected in a variety of archaeological ceramics. Charleston is known as the birthplace of the nation’s historic preservation movement and the center of a vibrant Gullah culture, whose ancestors were enslaved Africans. The first shots of the Civil War were fired there. Founded in 1773, The Charleston Museum is considered America’s first museum.

The English colony known as Carolina was a relatively late endeavor in British North America. Settlers arrived in the harbor formed by the Ashley and Cooper Rivers in 1670. This southern outpost was part of Spanish lands known as La Florida, and the colony’s early decades were shaped by tensions between Spanish Florida and English Carolina. The proximity of the Spanish settlement also created opportunities for trade, sanctioned and unauthorized. The colony attracted a diverse group: Englishmen, Scots, French Huguenots, English Dissenters, Jews. Settlers from British Caribbean islands, particularly Barbados, transported a cultural model of political acumen, economic improvement, and a plantation system based on slave labor. African slaves were among the earliest residents.[1]

The port city developed in tangent with the region’s plantation economy, and those rural sites augment our knowledge about the material culture of Carolina. This interplay between town and country continues to drive the cultural landscape of Charleston.[2] Deerskins traded from Native Americans, cattle, and timber supported the colony before rice made landowners wealthy. First introduced to Charleston in the 1680s, the commercial success of rice and indigo led to slow but steady growth of the peninsular city known as Charles Town (fig. 1).

The Grand Modell plan drafted by the Lord Proprietors of Carolina, the English overseers who held the royal charters, provided a settlement plan for the colony. This plan imposed some order on land traversed by creeks and marshes. Colonists constructed a defensive wall surrounding sixty-two acres fronting the Cooper River, protecting the city from outside threats. With Charleston’s economic success, however, the city grew beyond the protective walls.[3]

By the 1730s inland swamp rice production turned a great profit. African slaves familiar with the terrain from work as cattle hunters cleared freshwater swamps and built dams, gates, ditches, and canals to flood and drain rice fields.[4] Fires and hurricanes struck regularly, but the population and the city grew relentlessly during the eighteenth century (figs. 2, 3).

The per capita income of whites was among the highest in the colonies. Furniture, silver, table- and teawares, textiles, paintings, and other symbols of wealth poured into the colony. Imports were matched by products from local craftspeople and their slaves. Personal wealth was displayed in new public buildings and private homes.[5]

Charleston was occupied by the British during the American Revolution, but the war only briefly interrupted economic growth. Tidal rice culture increased the production per acre and Sea Island cotton became profitable. After a national depression in 1819, Charleston’s economy began a decline. New rail and steam networks bypassed Charleston, and by the 1850s the fourth largest colonial city fell to twenty-second (fig. 4).[6]

As the Civil War approached, South Carolina led the fiery rhetoric that defended slavery and called for secession from the United States. Confederate artillery opened fire on Fort Sumter in April 1861. Bombardment of the city caused some damage, but not as much as the Great Fire of 1861 that cut a diagonal swath across the peninsula. The emancipation of enslaved laborers and the vicissitudes of international markets effectively ended profitable rice production. Phosphate mining, lumbering, and truck farming diversified the postbellum economy, but it was not until the mid-twentieth century that Charleston’s economy rebounded. Economic stagnation had inadvertently preserved much of the city’s architectural heritage. Appreciation of the history and architecture was fostered by the Charleston Renaissance movement in the early twentieth century; the city’s first reported archaeological discovery—the defensive wall—occurred in 1929.[7]

Charleston’s rich archaeological heritage has been explored through dozens of excavation projects spanning five decades.[8] Since the 1960s, archaeological excavation of Charleston’s urban sites has included public buildings and spaces, defensive features, commercial properties, markets, and residences. Most are the homes of wealthy merchants and planters, but some are more modest dwellings of the city’s middling and poor. Townhouse sites include those open to the public as house museums and private residences. The Charleston Museum, the Drayton Hall Preservation Trust, Historic Charleston Foundation, and South Carolina State Parks house archaeological collections from contexts spanning the late seventeenth to the late nineteenth centuries. The Charleston Museum curates nearly three million artifacts, while Drayton Hall houses over one million. Ceramics cover the entire spectrum of earthenwares, stonewares, and porcelains made and used throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. A port city with a global reach, Charleston’s collection is dominated by British ceramics, but includes wares from Asia, the Caribbean, France, and Spain.

Barbadian Redware

Barbadian Redwares are wheel-thrown, kiln-fired earthenwares manufactured by enslaved Africans on the Caribbean island of Barbados.[9] Barbadian Redware is apparently rare in Charleston (fig. 5) but has appeared in two archaeological sites to date: Charles Towne Landing State Historic Site and St. Giles Kussoe. The presence of these fragments suggests a cultural connection between Barbados and Charleston.[10] The historical relations between Barbados and the South Carolina Lowcountry are compelling. From the aborted settlement at Cape Fear in 1664 to the first permanent colony at Charles Town in 1670, the progeny of Barbadian planters brought the Barbados cultural hearth to South Carolina.[11]

Using local clay resources, Barbadian potters produced sugar molds and molasses jars required by the island’s sugar economy. Beginning in the mid-seventeenth century, the “Sugar Revolution” made locally produced processing vessels ubiquitous in Barbados (fig. 6). Just five years after its initial introduction to Barbados, sugarcane supplanted both tobacco and cotton, transforming the island into a vast network of sugar-production complexes that included mills, boiling houses, curing facilities, and potteries. Slave holdings in excess of 300 people of African descent were present at nearly every plantation. By 1650 Barbados was the leading producer of sugar in the English realm, and the leading producer of red-earthenware sugar wares and a whole array of domestic wares.

Black Delftware Teapot, Drayton Hall

John Drayton (1715–1779) purchased Drayton Hall on March 2, 1738. Based on a 1737 advertisement for the property, it is clear that structures were present at the time of purchase. The ad references a “very good Dwelling house, Kitchen, and several out-houses, with a very good orchard consisting of all sorts of fruit trees.”[12] Recent documentary and archaeological research (fig. 7) reveals that from 1718 to 1734 the owner of the property was Francis Yonge.[13] Yonge served as South Carolina’s surveyor general from 1716 to 1719 and as colonial agent from 1721 to 1733. As agent, he frequently traveled to London on behalf of South Carolina colonists. This transatlantic mobility might account for the rare material culture found in “pre-Drayton” archaeological contexts. Of particular note was the discovery of six fragments from an early-eighteenth-century Dutch black delft teapot (fig. 8).

Black delft was produced by a handful of Dutch factories from about 1670 to 1740. Intact black delft vessels are extremely rare; only about sixty-five are known. Based on the style of the black background around the polychrome decoration, the recovered fragments are almost certainly from The “Greek A” Factory (1674–1722). Many of the surviving examples were produced between 1701 and 1722 and are marked “PAK” for Pieter Adriaensz Kocks. The decorations on the Drayton Hall fragments are very similar to those on a teapot in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (fig. 9).[14] These rare fragments are the only recognized archaeological examples of this variety of delft in North America.

Chinese Export Porcelain Teabowl, Dock Street Theatre

Charleston’s prosperity supported a rich material and social world, manifest in the construction of the second colonial theater in the United States—Dock Street Theatre, built in 1736 but destroyed by fire in 1754. A 2008 renovation project of the later 1809 building revealed a brick foundation beneath a concrete floor and three feet of sterile sand fill (fig. 10). Archaeologists called to the site determined that it was a privy, filled with dark organic soil and debris (fig. 11). The soil held only a few ceramic and glass artifacts, but they were large and readily identifiable as types from the second quarter of the eighteenth century.[15] This small feature and archaeological collection reflect the activities and clientele of an early colonial social center.[16]

Chinese export teawares come from archaeological deposits throughout Charleston, and proliferate after the 1730s, when rice made Charleston wealthy. Most eighteenth-century teabowls have low rounded shoulders, but a Chinese porcelain vessel from Dock Street is fairly unusual, with straight, flaring sides and a narrow foot ring (fig. 12). The style of the bowl can be dated to the first quarter of the eighteenth century and attributed to the Fukien (Fujian) province, via the Dutch trade.[17]

Other teawares from the Dock Street deposit were English white salt-glazed stonewares. Pollen preservation was good and analysis identified a number of flowering plants such as carnations, lilies, and honeysuckle that might represent floral arrangements or decoration. The equally robust animal remains included small bones from the end of chickens’ wings. Zooarchaeologist Elizabeth Reitz suggests that the flight feathers from these wing bones were used in the theater as quill pens or as plectra for a harpsichord.

Colonoware

Colonoware is South Carolina’s contribution to the pottery world, and the low-fired, unglazed earthenware is as ubiquitous as it is contentious. This ware is found on almost every plantation site in coastal South Carolina, particularly in slave quarters, where it sometimes accounts for more than half of the recovered ceramic fragments. It is also part of all urban site collections.

The pottery was first identified as “Colono-Indian ware” and attributed to trade with Native Americans. In the late 1970s archaeologists began excavating plantation sites and recovered the ware in great quantity. Ron Anthony, Leland Ferguson, Pat Garrow, and Thomas Wheaton then suggested most of this earthenware was the product of African-American potters.[18] Since then, scores of archaeologists have analyzed thousands of colonoware fragments and defined varieties. Today, many researchers feel that colonoware is our best example of “tangible interaction,” material culture resulting from cultural syncretism.

The ware was common throughout the eighteenth century, though recent excavations expand the date range. At least some of the ware was likely produced for sale, either in Charleston markets or to individual plantations.[19] Other vessels were made on plantations, where they were used and discarded. A late-eighteenth-century variety appears to be the product of Catawba potters from the western piedmont of South Carolina, traveling and selling their wares.[20] Regardless of the source, colonowares were routinely used in the kitchens of white slave-owning families and in the cabins of the enslaved. The most common forms are shallow open bowls and globular jars (figs. 13, 14). Occasionally, colonowares copy European forms.

John Bartlam’s Ceramics

Charleston’s ceramic market was dominated by wares from Europe and Asia. Only two potters have been identified that worked in colonial South Carolina, and only one has been documented archaeologically. In 1763 master potter John Bartlam immigrated to Carolina from the Staffordshire region of Britain to search for clays appropriate for English-style tablewares. He found good clay at Cain Hoy on the Wando River north of Charleston. By 1765 Bartlam had established a pottery manufactory where he employed African-Americans as apprentices. In 1769 he moved his business to Charleston and remained there until 1773. Bartlam then moved his efforts to Camden, South Carolina and developed a marketable “Queen’s Ware” that he exported to Charleston.

George Terry, Brad Rauschenberg, and Stanley South searched for the Cain Hoy pottery for decades. They found the site just as the property was subdivided into small lots and sold for development. South excavated three lots with Carl Steen and Jim Legg in 1991–1992.[21] Although a kiln was not found, the recovery of bisque ware, wasters, and unique pottery styles is proof that Bartlam’s pottery at Cain Hoy was discovered. Lisa Hudgins completed analysis of Bartlam’s pottery and refined the criteria for identifying Bartlam’s wares, described in detail in the 2007 and 2009 volumes of Ceramics in America.[22]

John Bartlam’s Cain Hoy products include lead-glazed earthenware, cauliflower- and pineapple-shaped wares, and Whieldon-type wares (fig. 15). Bartlam also experimented with soft-paste porcelain, a white-bodied ware decorated in blue (fig. 16).[23] Only a few complete examples of Bartlam’s wares have been documented.

Chinese Yixing Teapot

I received a most fortuitous telephone call from architect Joe Opperman in the fall of 1994. Workers adding an elevator shaft to the South Carolina Society Hall on Meeting Street had encountered a deposit of relatively intact artifacts. Would the museum like to pick them up? You bet! The box of artifacts appeared to be from a privy pit or trash pit that had been filled in the 1770s. A lovely sprigged creamware teapot protruded from the soil profile; the college intern accompanying me quickly rescued it.

This time capsule contained ceramics that were popular in the third quarter of the eighteenth century and were likely used together, or at least discarded together. Also included were familiar molded plates in Whieldon ware, white salt-glazed stoneware, and feather-edged creamware. Kitchen wares included a combed and trailed slipware bowl from the Staffordshire potteries in England, and black lead-glazed redware pots and pans plus a small cook pot from Philadelphia potteries. A Moustiers yellow-on-white bowl came from France; a small storage jar was Spanish. There was even a large colonoware bowl.[24] One vessel, though, was unique to Charleston: a Yixing stoneware teapot, the only known archaeological example in South Carolina. Its relatively large size suggests that it was made for the Western market. Its recovery with the other ceramics illustrates the global reach of Charleston’s mercantile community. The vessel is shown here with a circa 1825 example of Yixing stoneware from The Charleston Museum’s decorative arts collection (fig. 17).

Dragon Teapot, Drayton Hall

Drayton Hall (ca. 1750) is the earliest and finest example of Georgian Palladian architecture in North America. Its builder, John Drayton (1715–1779), composed his home in the style of an English country estate (fig. 18). Through archaeological excavations of the property, initiated in 1975 by the National Trust for Historic Preservation and continuing now by the Drayton Hall Preservation Trust, it is clear that the material culture chosen to furnish the home was equally refined and at the cutting edge of English fashion. One distinctive example is represented by seven fragments of an English dry-bodied stoneware teapot, likely made in 1765–1770 in Staffordshire, England (fig. 19).[25]

The stoneware fragments have a dark-brown paste with buff-colored slip and mold-applied decoration in brown. The sprig-molded decorations feature a central, stylized Chinese dragon motif with an elaborate floral border along the base and shoulder of the vessel. The teapot is cylindrical, and intact examples show that the handles of these vessels are in the shape of molded bamboo. The fragments are a remarkable find for Charleston and in general; no evidence of this style of teapot being used in a colonial American context was known until this discovery at Drayton Hall.

A Tale of Two Punch Bowls

Fragments of punch bowls are common finds at Charleston sites, particularly at the townhouses of the city’s gentry. The vessels were part of communal, celebratory drinking and came in a number of ceramic types and range of sizes. In late-eighteenth-century Charleston, there was evidently much to celebrate. Two relatively complete examples tell different parts of the Charleston story (fig. 20).

A British delftware punch bowl proclaiming “Success to Trade” came from the Exchange and Customs House (fig. 20, left). Built in 1771, the grand public building dominated the harbor and was visual testament to the city’s economic success. Excavations inside the building in 1965 and 1986 revealed the Half Moon Battery, part of the city’s early defenses, and produced collections spanning the eighteenth century.[26]

Excavations in the 1970s of the yard of the Heyward-Washington House by Dr. Elaine Herold produced an archaeological collection unparalleled in size and scope.[27] Thomas Heyward, signer of the Declaration of Independence, built this imposing townhouse in 1772 (fig. 21). He and his brother-in-law George Abbot Hall were imprisoned in St. Augustine during the 1780s British occupation of Charleston. However, their wives remained in the Charleston house during their period of imprisonment. After the Revolution, the Heywards moved to their plantation, and the empty townhouse was rented to President Washington during his 1791 tour of Southern states. A nearly complete bowl of Chinese export porcelain (see fig. 20, right) was recovered in the excavations among other examples of Chinese porcelain sets of teaware, saucers, plates, and serving vessels.

Earthenwares from Philadelphia

Utilitarian earthenwares are a significant part of Charleston’s ceramic assemblage (fig. 22). As the colonial period progressed, an increasing number of them were produced in the mid-Atlantic colonies, particularly by potters in Philadelphia. Advertisements in Charleston’s colonial newspapers reveal a lively trade with that city. The ads suggest that foodstuffs such as butter, flour, and bread regularly arrived from Pennsylvania; the archaeological record suggests shipments of American-made earthenwares also landed in Charleston on a regular basis. Charleston merchant Thomas Shute’s 1770 ad in the South-Carolina Gazette touted goods from Philadelphia, including “milk pans, large and small jugs, chamber, butter, and flower pots, jars, quart and pint mugs, porringers, and a variety of small items.”[28]

Carl Steen describes three types of decorated earthenwares that are common in Charleston. Trailed wares are large, red clay bowls or pans with flaring sides, decorated with trailed lines of white slip under a lead glaze. Combed wares are drape-molded plates with coggled edges, decorated with thick bands of white slip, combed into wavy lines. Clouded wares are small pedestaled bowls with a clear lead glaze on the exterior and a poured or sloshed slip filling the interior. In addition, there are undecorated lead-glazed earthenwares in various forms, from pitchers to open bowls to small cooking pots (fig. 23). Most Charleston sites yield earthenwares that were manufactured in the Philadelphia region; in the second half of the eighteenth century they make up nearly two percent of Charleston ceramics.[29]

Children’s Cups from Charleston Place

Charleston Place is the name of a luxury hotel that was erected in 1981 one block from the Charleston Market. The project was the cornerstone of Charleston’s revitalization efforts of the late 1970s and the first large-scale contract project required by federal mandate. Systematic excavations of dozens of individual properties by Nicholas Honerkamp of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga were followed by monitoring and salvage by The Charleston Museum. Those undertakings produced archaeological collections that span the nineteenth century, when the block bustled with commercial activity. Merchants built multistory structures along the front of long, narrow lots; they plied wares from shops on the ground floor and lived in rooms above. Fires in 1835 and 1838 destroyed portions of the block, making way for new masonry buildings. By the close of the nineteenth century, buildings covered eighty percent of the block.

Most of the archaeological deposits and features reflect the domestic lives of residents in the upper floors, although a few deposits of artifacts from the ground-floor retail and commercial establishments have been identified. Among the thousands of artifacts were small cups for children (fig. 24). Numerous vessels in pearlware, creamware, whiteware, and canary ware came from features filled between 1800 and 1840, the period when children’s ceramic items were popular.[30] The cups featured underglaze decoration, or enameling over a clear lead glaze, emblazoned with a name or a whimsical saying. Many of the prints illustrate benign children’s games, but the cup with the inscription “A PRESENT FOR WILLIAM” shows a scene of a dead cat hung from a tree (fig. 25).

Walter Edgar, South Carolina: A History (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1998).

Martha A. Zierden and Elizabeth J. Reitz, Charleston: An Archaeology of Life in a Coastal Community (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2016).

Jonathan Poston, The Buildings of Charleston: A Guide to the City’s Architecture (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press for the Historic Charleston Foundation, 1997).

Converse D. Clowse, Economic Beginnings in Colonial South Carolina, 1670–1730 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press for the South Carolina Tricentennial Commission, 1971); Richard D. Porcher Jr. and William R. Judd, The Market Preparation of Carolina Rice: An Illustrated History of Innovations in the Lowcountry Rice Kingdom (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2014); Hayden R. Smith, “Rich Swamps and Rice Grounds: The Specialization of Inland Rice Culture in the South Carolina Lowcountry, 1670–1861,” Ph.D. diss., University of Georgia, 2012; Peter H. Wood, Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1974).

Walter J. Fraser, Charleston! Charleston! The History of a Southern City (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1989); Bernard Herman, Townhouse: Architecture and Material Life in the Early American City, 1780–1830 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005); Maurie D. McInnis and Angela Mack, eds., In Pursuit of Refinement: Charlestonians Abroad, 1740–1860, exh. cat. (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press for the Gibbes Museum of Art, 1999).

Porcher and Judd, Market Preparation of Carolina Rice; Richard D. Porcher and Sarah Fick, The Story of Sea Island Cotton (Charleston, [S.C.]: Wyrick and Co., 2005); Theodore Rosengarten, “The Southern Agriculturist in an Age of Reform,” in Intellectual Life in Antebellum Charleston, edited by Michael O’Brien and D. Moltke-Hansen (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1986), pp. 279–94; Theodore Rosengarten, Tombee: Portrait of a Cotton Planter (New York: William Morrow, 1986).

Sidney R. Bland, Preserving Charleston’s Past, Shaping Its Future: The Life and Times of Susan Pringle Frost, 2nd ed. (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1999); James M. Hutchisson and Harlan Greene, eds., Renaissance in Charleston: Art and Life in the Carolina Low Country, 1900–1940 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2003).

All Charleston Museum site reports, including the Archaeological Contributions series, are available online at www.charlestonmuseum.org/research/archaeology-reports.

J. Harry Bennett, Bondsmen and Bishops: Slavery and Apprenticeship on the Codrington Plantations of Barbados, 1710–1838 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1958); Jerome S. Handler, “A Historical Sketch of Pottery Manufacture in Barbados,” The Journal of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society 30, no. 3 (1963): 129–53; Thomas C. Loftfield and James B. Legg, “Archaeological Evidence of Afro-Barbadian Life at Springhead Plantation, St. James Parish, Barbados,” The Journal of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society 43 (1993): 32–49; Michael J. Stoner, “Codrington Plantation: A History of a Barbadian Ceramic Industry,” master’s thesis, Armstrong Atlantic State University, 2000; Michael J. Stoner, “Material Culture in the City: Barbadian Redwares in Bridgetown,” The Journal of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society 49 (2003): 254–68.

Andrew Agha, “St. Giles Kussoe and ‘The Character of a Loyal States-man’: Historical Archaeology at Lord Anthony Ashley Cooper’s Carolina Plantation,” report on file, Historic Charleston Foundation, Columbia, S.C., 2012; Michael J. Stoner and Stanley A. South, “Exploring 1670 Charles Towne: 38CH1A/B, Final Report,” South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology Research Manuscript Series 230, Columbia, S.C., 2001.

Jack P. Greene, The Quest for Power: The Lower Houses of Assembly in the Southern Royal Colonies, 1689–1776 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Institute of Early American History and Culture at Williamsburg, Va., 1963); Jack P. Greene, Imperatives, Behaviors, and Identities: Essays in Early American Cultural History (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1992).

Property advertisement, The South Carolina Gazette, December 15, 1737.

Susan Baldwin Bates and Harriott Cheves Leland, Proprietary Records of South Carolina, Volume Three: Abstracts of the Records of the Surveyor General of the Province, Charles Towne, 1678–1698 (Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2007); Shi-pei Chu, “Francis Yonge, The First Regular Colonial Agent for South Carolina,” master’s thesis, University of South Carolina, 1960; Henry A. M. Smith, Rivers and Regions of Early South Carolina, 3 vols. in 1 (Spartanburg, S.C.: Reprint Co., in association with the South Carolina Historical Society, 1988).

Robert D. Aronson, Dutch Delftware: Including Selections from a Distinguished Manhattan Collector (Amsterdam: Aronson Antiquairs of Amsterdam, 2009); Caroline Henriette de Jonge, Delft Ceramics (New York: Prager Publishers, 1969).

Martha Zierden et al., The Dock Street Theatre: Archaeological Discovery and Exploration, Charleston Museum Archaeological Contributions 42 (Charleston, S.C.: Charleston Museum, 2009).

Zierden and Reitz, Charleston, pp. 122–25.

Robert Leath, director of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA), email communication, November 12, 2008; Elinor Gordon, ed., Chinese Export Porcelain: An Historical Survey, Antiques Magazine Library 3 (New York: Main Street/Universe Books, 1975); Robert Leath, “After the Chinese Taste: Chinese Export Porcelain and Chinoiserie Decoration in Eighteenth-Century Charleston,” Historical Archaeology 33, no. 3 (1999): 48–61.

Ronald W. Anthony, “Tangible Interaction: Evidence from Stobo Plantation,” in Another’s Country, edited by J. W. Joseph and Martha A. Zierden (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002), pp. 45–64; Leland Ferguson, Uncommon Ground: Archaeology and Early African America, 1650–1800 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992); Thomas Wheaton and Patrick Garrow, “Acculturation and the Archaeological Record in the Carolina Lowcountry,” in The Archaeology of Slavery and Plantation Life, edited by Theresa A. Singleton (New York: Academic Press, 1985), pp. 239–59.

J. W. Joseph, “Colonoware for the Village—Colonoware for the Market,” South Carolina Antiquities 36 (2004): 72–86.

Brett H. Riggs, R. P. Stephen Davis, and Mark R. Plane, “Catawba Pottery in the Post-Revolutionary Era: A View from the Source,” North Carolina Archaeology 55 (2006): 60–88; Carl Steen, “An Archaeology of the Settlement Indians of the South Carolina Lowcountry,” South Carolina Antiquities 44 (2012): 19–34.

Stanley A. South, John Bartlam: Staffordshire in Carolina, Research Manuscript Series 231 (Columbia: South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2004)

Lisa Hudgins, “John Bartlam’s Porcelain at Cain Hoy: A Closer Look,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), pp. 203–8; Lisa Hudgins, “Staffordshire in America: The Wares of John Bartlam at Cain Hoy, 1765–1770,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2009), pp. 69–80.

Robert Hunter, “John Bartlam: America’s First Porcelain Manufacturer,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), pp. 193–96.

Martha Zierden, “The Archaeological Signature of Eighteenth-Century Charleston,” in Material Culture in Anglo-America: Regional Identity and Urbanity in the Tidewater, Lowcountry, and Caribbean, edited by David S. Shields (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2009), pp. 267–84.

Diana Edwards and Rodney Hampson, English Dry-Bodied Stoneware: Wedgwood and Contemporary Manufacturers, 1774–1830 (Woodbridge, Suffolk, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1998); Nancy Gunson, “Red Stoneware,” in Stonewares & Stone Chinas of Northern England to 1851: The Fourth Exhibition from the Northern Ceramic Society, edited by T. A. Lockett and P. A. Halfpenny (Stoke-on-Trent, Eng.: City Museum and Art Gallery, 1982), pp. 53–58; Robert Hunter, “Digging in the Drawers at Drayton Hall: A Discovery of a Staffordshire Stoneware Teapot at Drayton Hall,” Ceramics in America Blog, http://www.chipstone.org/post.php/17/A-Discovery-of-a-Staffordshire-Stoneware-Teapot-at-Drayton-Hall/ (posted July 9, 2014).

Elaine Herold, “Archaeological Research at the Exchange Building, Charleston, SC: 1979–1980,” report on file, The Charleston Museum, Charleston, S.C., 1981.

Elaine Herold, “Preliminary Report on the Research at the Heyward-Washington House,” report on file, The Charleston Museum, Charleston, S.C., 1978; Martha Zierden and Elizabeth Reitz, Charleston through the Eighteenth Century: Archaeology at the Heyward-Washington House Stable, Archaeological Contributions 39 (Charleston, S.C.: The Charleston Museum, 2007).

Carl Steen, “Pottery, Intercolonial Trade, and Revolution: Domestic Earthenwares and the Development of an American Social Identity,” Historical Archaeology 33, no. 3 (1999): 62–72.

Deborah L. Miller, Meta F. Janowitz, and Allan S. Gilbert, “Identifying Red, Brown, and Black Philadelphia ‘China’ through Compositional Analysis: Initial Results,” American Ceramic Circle Journal 19 (2017): 97–121; Zierden, “Archaeological Signature of Eighteenth-Century Charleston,” pp. 267–84.

Martha Zierden and Debi Hacker, Charleston Place: Archaeological Investigation of the Commercial Landscape, Archaeological Contributions 16 (Charleston, S.C.: The Charleston Museum, 1987).