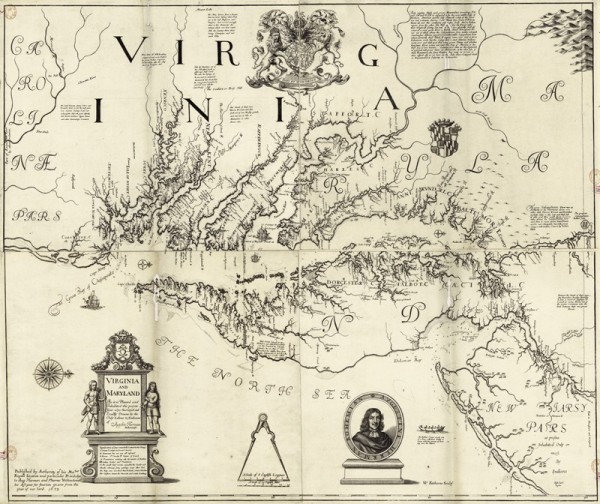

Augustine Herrman, Map of Virginia and Maryland, 1670. 31 1/2 x 37 3/8". (Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., MSA SC 5339-1-172.)

Detail of the map illustrated in fig. 1, showing the location of St. Mary’s City.

Costumed interpreters engaged in living history at the Godiah Spray Plantation, Historic St. Mary’s City, Maryland. (Courtesy, Historic St. Mary’s City; photo, Donald L. Winter.)

The Maryland Dove, a full-scale replica of the square-rigged ships that brought settlers to St. Mary’s City. (Courtesy, Historic St. Mary’s City; photo, Donald L. Winter.)

The reconstructed brick chapel at Historic St. Mary’s City. (Courtesy, Historic St. Mary’s City; photo, Donald L. Winter.)

The reconstructed brick statehouse of 1676. (Courtesy, Historic St. Mary’s City; photo, Donald L. Winter.)

Archaeological site, St. Mary’s City, showing foundations of Leonard Calvert’s House, which became the first Statehouse of Maryland. (Courtesy, Historic St. Mary’s City; photo, Alexander Henderson Morrison II.)

Medallion fragment, Westerwald, Germany, ca. 1620. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Historic St. Mary’s City; photo, Donald L. Winter.) Found in the moat surrounding Pope’s Fort.

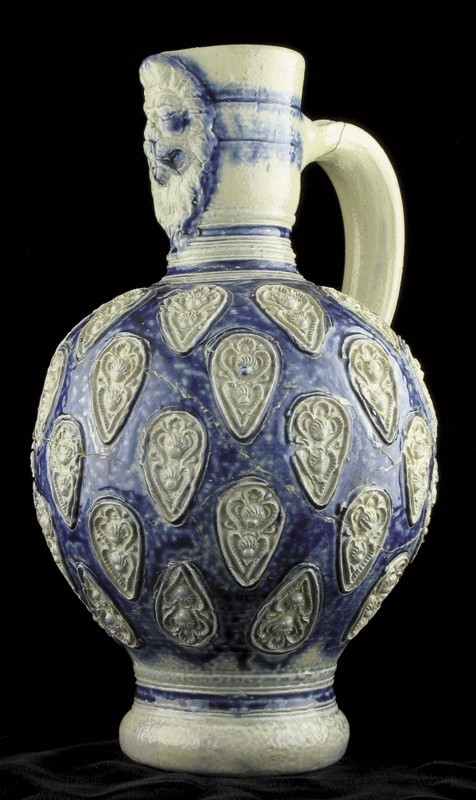

Ewer, Westerwald, Germany, ca. 1660. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/8". (Courtesy, Historic St. Mary’s City; photo, Donald L. Winter.)

Detail of the ewer illustrated in fig. 9.

Bottle or cruet, Donyatt, England, ca. 1670–1680. Sgrafitto-decorated slipware. H. 3 11/16". (Courtesy, Historic St. Mary’s City; photo, Donald L. Winter.) This view shows the rendering of a swan.

Reverse view of the vessel illustrated in fig. 11, showing the rendering of a rooster.

The Print House in St. Mary’s City following reconstruction, ca. 1675–ca. 1700. (Courtesy, Historic St. Mary’s City; photo, Donald L. Winter.)

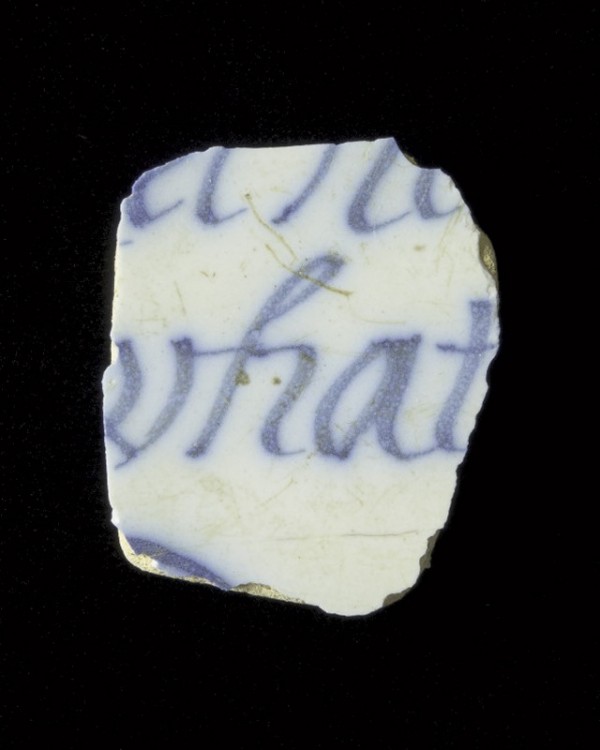

Plate fragment, English, 1680–1700. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 7/8". Hand-painted in cobalt: “[undecipherable] / what . . . ” (Courtesy, Historic St. Mary’s City; photo, Donald L. Winter.)

Merryman plate, one of a set of six, probably Dutch, possibly British, ca. 1684. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 1/8". (Courtesy, Historic Deerfield; photo, Silas D. Hurry.)

Morgan Jones pitcher in situ, St. Mary’s City, 1977. (Courtesy, Historic St. Mary’s City; photo, Garry Wheeler Stone.)

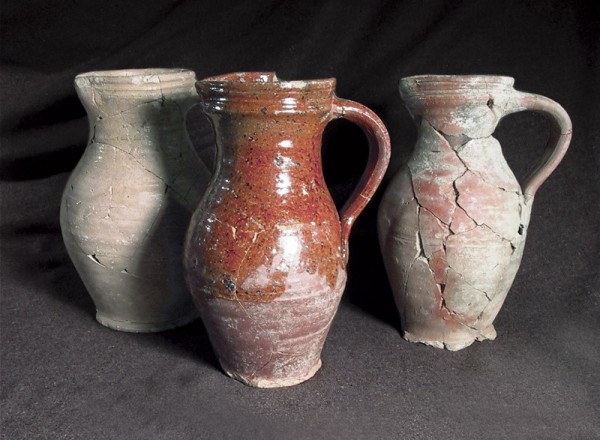

Pitchers, Morgan Jones, St. Mary’s County, Maryland, or Westmoreland County, Virginia, 1661–1680. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. (left to right) 9 5/8", 9 5/8", 9 7/8". (Courtesy, Historic St. Mary’s City; photo, Donald L. Winter.)

Interior of the St. John’s Site Museum. (Courtesy, Historic St. Mary’s City; photo, Donald L. Winter.)

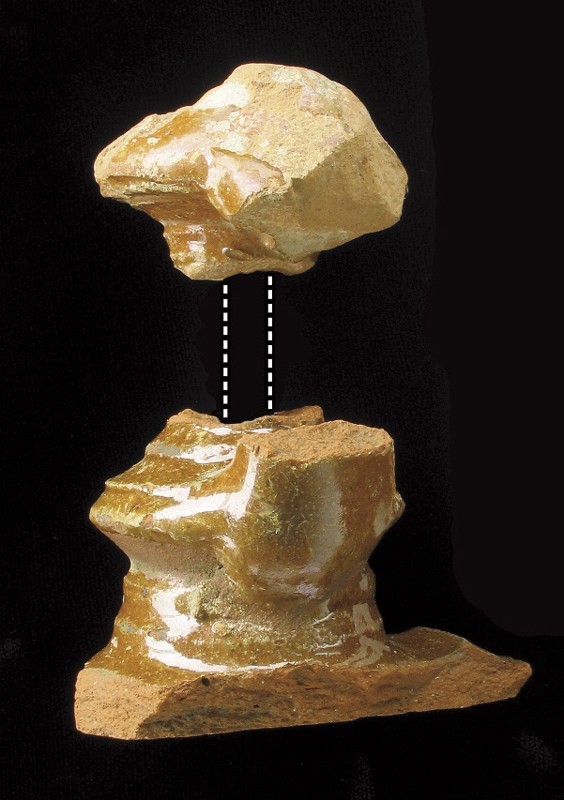

Candlestick fragments, Surrey-Hampshire, England, 1600–1650. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic St. Mary’s City; photo, Donald L. Winter.) The top element of this Border Ware candlestick was found in 1974, the bottom in 2003.

Jug fragment, Westerwald, Germany, dated 1646. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Historic St. Mary’s City; photo, Donald L. Winter.)

Abraham Diepraam (1622–1670), The Barroom (detail), 1665. Oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Rijksmuseum.)

One of the deflt drinking bowls in situ at the St. John’s site. (Courtesy, Historic St. Mary’s City; photo, Alexander Henderson Morrison II.)

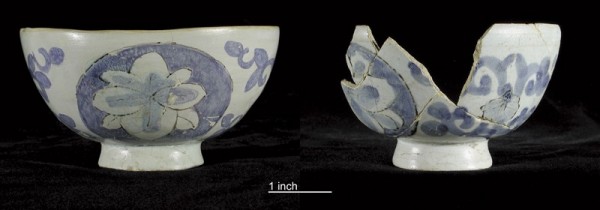

Bowls, Northern Netherlands, 1680–1700. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. (left) 3 5/16", (right) 3 1/4". (Courtesy, Historic St. Mary’s City; photo, Donald L. Winter.) These drinking bowls were excavated from redeposited cellar fill at the St. John’s site.

Tea bowl or coffee cup, Kütahya, Turkey, 1690–1710. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 2 5/8". (Courtesy, Historic St. Mary’s City; photo, Donald L. Winter.) This Ottoman-period vessel is from the Garret Van Sweringen site, St. Mary’s City.

Artist’s conception of Van Sweringen’s Inn in 1692. (Courtesy, Historic St. Mary’s City; artwork, Leslie Barker, 2006, © Leslie Barker.)

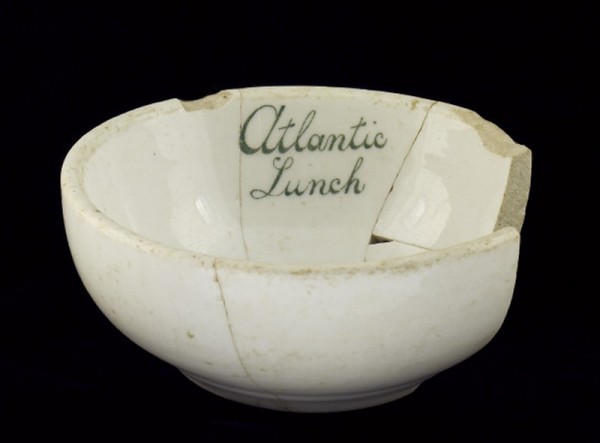

Bowl, Carr China, Grafton, West Virginia, ca. 1911. Vitreous stone china. D. 5". (Courtesy, Historic St. Mary’s City; photo, Donald L. Winter.)

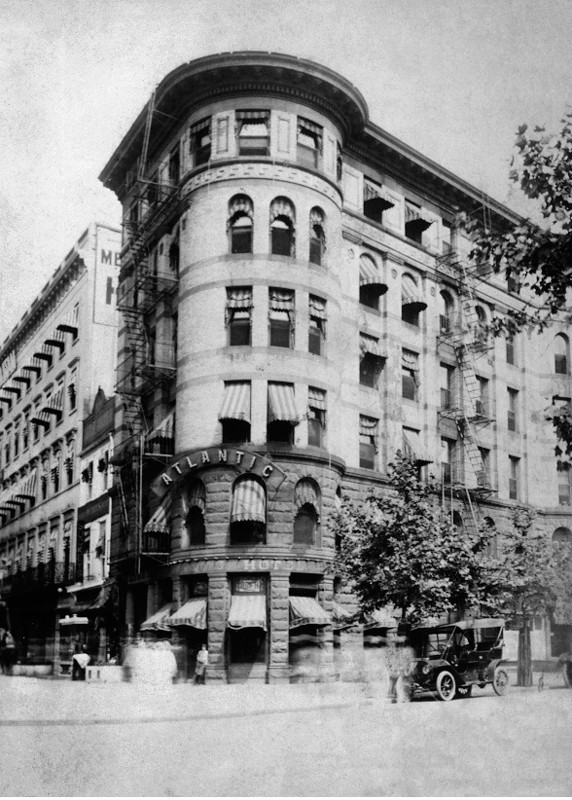

The Atlantic Hotel in Washington, D.C., early twentieth century. (Photo, Mrs. Harry Carroll Dalton.)

St. Mary’s City was the founding site and first capital of Maryland, established in 1634 and the first of the proprietary colonies. A proprietary colony was actually the possession of one person or group of persons and ownership passed down through the family. Maryland was the possession of the Lords Baltimore, the Calvert family.

George Calvert was the first Lord Baltimore and he had served as the Secretary of State for James I of Great Britain. Calvert had an interest in colonial development and, while still the principal secretary, had invested in a colonial endeavor in Newfoundland. Following his resignation as secretary in 1625, Calvert announced his conversion to Roman Catholicism.

For his service, King Charles I raised Calvert up into the Irish nobility as Lord Baltimore. Calvert emigrated to his Newfoundland possession in 1628. After a severe winter in residence and numerous trials and setbacks, Calvert abandoned his colony and sailed south to Jamestown, where he was met with a less than enthusiastic welcome on account of his Roman Catholicism. Calvert refused to take the Oath of Supremacy demanded by the Virginians, but did like the look of the land and the more salubrious climate. He returned to England and began the process of lobbying his monarch for a new grant of land in the area of the Chesapeake Bay. George Calvert died before the grant was finalized, so it fell to his son Cecil, the second Lord Baltimore, to organize the settlement of what came to be known as Maryland, named for Henrietta Maria, wife of Charles I.

Maryland was founded at St. Mary’s in 1634 with Cecil’s brother Leonard Calvert as governor. In order to allow Roman Catholics to practice their faith, the Calverts decreed that all Christian religions were allowed. The first years proved successful, with numerous investors who gained the rights to property by transporting labor to the new colony.

From fairly early on, the colony focused on the growing of tobacco for export. However, things did not remain calm in the colony with the coming of the English Civil War. In 1645 the colonial government was overthrown by an English privateer, Richard Ingle, who joined with disgruntled Protestants. Leonard Calvert escaped to Virginia, and eventually returned with mercenaries and retook the colony. Leonard died shortly thereafter.

The Calvert policy of religious tolerance was codified in 1649 in the passage of a law entitled “An Act Concerning Religion.” During the Commonwealth period, the Calverts again lost control of the colony until it was restored to them by Oliver Cromwell. With the restoration of the Stuart monarchy in England and the active involvement of the Calverts in the affairs of the colony, Maryland entered a “golden age.” Cecil Calvert’s son Charles was governor while Cecil’s half-brother Philip served as chancellor.

A period of peace, expansion, and growth lasted for a number of decades. Cecil Calvert died in 1676 and Charles became the third Lord Baltimore. Philip Calvert died in 1683. In 1689, while Charles Calvert was in England, another revolt was staged by the Protestants that roughly coincided with the Glorious Revolution in England. As James II, a Catholic, was deposed from the throne of England in favor of his Protestant daughter Mary and her husband, William, so did Maryland fall from the hands of the Catholic Calverts, not to be returned until the conversion of Charles’s son to Protestantism in the eighteenth century. With the fall of the Catholic government, the capital was moved from St. Mary’s City to Annapolis. The city was rather quickly abandoned and converted into individual plantations (figs. 1, 2).

St. Mary’s City ceased to be a city with the end of the seventeenth century, and the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were rather quiet times. In 1840 what is now St. Mary’s College of Maryland was established as a “monument” school to commemorate the founding site of the state. In the 1960s, in an effort to bring about economic development through tourism, Historic St. Mary’s City was established by the state of Maryland. The museum has grown from an original holding of one-quarter acre to an outdoor history museum of more than 840 acres (figs. 3-6). Since shortly after the establishment of the museum, archaeology has been one of the prime movers in discovering and re-creating this unique Tidewater treasure. All of the ceramics included in this article are the result of sustained archaeological research spanning nearly fifty years.

Rhenish Westerwald Stoneware from Pope’s Fort Moat

Westerwald blue and gray stonewares are among the most diagnostic seventeenth-century ceramics typically found in Chesapeake archaeological sites. A fragment of a large blue-and-gray Rhenish stoneware jug was found in 1981 during the search for Leonard Calvert’s house (figs. 7, 8). As part of this work, evidence of a long-forgotten English Civil War fortification known as “Mr. Pope’s Fort” was encountered while replacing a modern septic tank associated with an 1840s plantation house. The “fort” was a dry moat and palisade that was built around Leonard Calvert’s house by Nathaniel Pope, who had joined Richard Ingle in a revolt to overthrow the Calvert colony in the name of Parliament. Ingle had arrived in the colony with letters of marque and in the service of Parliament against the Stuart king.[1]

The fragment illustrated in figure 8, found in the moat, is part of a medallion that depicts an individual with a huge bunch of grapes. A similar but more complete fragment is illustrated in Gisela Reineking-von Bock’s Steinzeug and bears the date 1617.[2] The medallion found in the moat also references Numbers 13:23–33 in the King James Version of the Bible: “And they came unto the brook of Eshcol, and cut down from thence a branch with one cluster of grapes, and they bare it between two upon a staff.” The jug probably had two of these medallions, as suggested by other fragments that were found.

A reexamination of pottery previously recovered from the John Hicks site has identified a Westerwald fragment that bears an identical cartouche.[3] The Hicks site dates to the second quarter of the eighteenth century but the seventeenth-century fragment appears to have been collected as a curiosity by its eighteenth-century occupants.

Westerwald Stoneware Ewer from Smith Outbuilding

Excavations in Historic St. Mary’s City have yielded rather remarkable examples of the art of the stoneware potters of the Rhine Valley in what is now Germany (fig. 9).[4] This salt-glazed stoneware ewer, with its tightly constricted neck, is decorated in cobalt blue and embellished with crisp sprig-molded decoration. At one time it had a metal mount and lid. The vessel bears an elaborately molded masquette of the face of a lion. Reineking-von Bock illustrates a fair number of comparable vessels, and a very similar though much more fragmentary example was recovered in excavations at the St. John’s site in St. Mary’s City.[5]

Our specimen was found in a cellar hole previously excavated by Henry Chandlee Forman, an archaeologist working in St. Mary’s in the 1930s and 1940s.[6] When we removed Dr. Forman’s fill, a distinct cultural feature was apparent in the floor of the cellar. Excavation of this subfloor intrusion yielded all of the fragments of the vessel illustrated in figure 9, along with the remains of at least nine very elaborate façon de Venise drinking glasses.[7] This association suggests to us that a domestic catastrophe of some magnitude in the household caused these valuable albeit fragile household objects to break. It was perhaps a mishap that a servant attempted to mitigate by burying the “evidence” in a hole dug into the floor of a cellar.

Donyatt Sgraffito Bird Bottle

This small vessel appears to be either a cruet or a petite bottle. It was discovered by Henry Chandlee Forman in the same refuse-filled cellar that yielded the lion-faced jug described above.[8] The vessel has a reddish paste and is overall slipped with white clay. The clay was scratched through in the style of decoration known as sgraffito. The decoration depicts two different types of birds, apparently a swan (fig. 11) and a rooster (fig. 12). The letter “F” is inscribed opposite the now-missing handle.

Archaeologist Taft Kiser helped us identify the bottle as Donyatt slipware, an identification subsequently confirmed by Richard Coleman-Smith, who directed major investigations into the Donyatt potteries in Somerset, U.K.[9] Fragments of at least one additional Donyatt dish were identified in the same deposit.

While the Donyatt potteries were in operation from the mid-thirteenth century through the early twentieth century, examples always appear as a minority ware on colonial sites in North America. Publishing their results in 2005, Coleman-Smith, Kaiser, and Michael Hughes identified only thirty-three examples of Donyatt on seventeenth- and eighteenth-century sites in Maryland and Virginia.[10] All of the Maryland examples were from St. Mary’s City. The authors point out that this is a surprisingly small amount considering that hundreds of examples of North Devon sgraffito have been discovered in the same region.[11]

Merryman Plate Fragment

Excavations at the Print House site, thought to have been the shop of colonists William and Dinah Nuthead (fig. 13), recovered a fragment of a delft plate with the word “what” in blue script (fig. 14). Our research of antique delft inscriptions suggested that the fragment was from what is known as a “Merryman” plate (fig. 15).

Starting around 1680 and continuing through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Merryman plate sets were made in England and the Netherlands. Relatively rare in museum collections, fragments of only two have been found on archaeological sites in North America.[12] All appear to have been decorated in cobalt and contained the same basic lines of doggerel verse:

What is a Merryman

Let him do what he can

To entertain his guests

With wine and merry jest

But if his wife does frown

All merriment goes down

The motif was particularly popular in the 1680s and 1690s—dated examples occur as early as 1682—and had an arabesque style of decoration. It made a comeback in the 1720s–1740s, when the decoration was dominated by a simple wreath surround.[13]

Some have suggested that the display of these plates in a household represents a turn toward gentility; this author believes the sentiment reflects a common theme of hospitality and the need for restraint created by the tempering influence of a female presence.[14]

Morgan Jones Pitchers

During the 1600s almost all manufactured goods used by Maryland’s settlers were imported from England or Europe. Few of the craftsmen who settled in the Chesapeake region actually pursued their profession in Maryland, as it was generally more profitable to grow tobacco. An exception is Maryland’s first recorded potter, Morgan Jones.

Jones immigrated in 1661 as an indentured servant to Robert Slye, one of the most successful merchants in seventeenth-century Maryland. Slye’s plantation was located near Bushwood on the Wicomico River in St. Mary’s County. When Slye died in 1671, his probate inventory listed a building called a “potthouse” as well as a large number of butter pots, milk pans, and porringers.[15]

After his service to Slye, it seems that Jones migrated to Virginia. By 1669 he was running a pottery kiln at Glebe Harbor in Westmoreland County that was excavated in 1973 by William Kelso and Edward Chappell.[16] Pottery attributed to Morgan Jones, earthenware with a lead glaze in brown, tan, and orange colors, is one of the most common types of ceramics found on sites in St. Mary’s City dating to the 1660s and early 1670s (fig. 16). Characteristic shapes include pitchers (fig. 17), cups, pans, and small bowls. Examples of his work have been found on a number of seventeenth-century sites in Maryland and Virginia.[17] Jones appears to have been very successful. One of his business partners in Virginia, John Quigley, later became the principal contractor for building Maryland’s first brick statehouse in 1676.

Border Ware Candlestick

Excavations at the St. John’s site in St. Mary’s City were undertaken beginning in 1972. The site, which was occupied from 1638 to circa 1715, had decayed and was torn down to make way for agriculture. After a hectic campaign of intense investigations lasting through 1976, the museum at Historic St. Mary’s City built a “temporary” structure over the architectural remains with the hope of developing the site into a major museum. More than thirty years later, in 2008, the St. John’s Site Museum finally became a reality (fig. 18).

As part of the effort to construct the museum, a fresh campaign of excavations was undertaken and thousands of additional artifacts were discovered. The 1970s excavations had yielded the top element of the object illustrated in figure 19. It was not until 2003 that the bottom piece shown, a basal fragment, was discovered. With the assistance of Bly Straub and Jacqui Pearce, it was identified as a Border Ware candlestick. Border Wares subsume a range of pottery made in related kilns in the area of the border of Surrey and Hampshire counties southeast of London. Pearce directed a major analysis of these ceramics, which was published in 1992.[18]

Border Wares occur in a number of distinct types. The most common variety found in St. Mary’s City is a white clay body variant that at one time was known as Surrey Ware. Our specimen correlates nicely to other candlestick forms identified by Pearce in her analysis.

Westerwald Jug with Applied Lion

Discovered in the late 1980s, this stoneware fragment was found on the shore not far from where the Maryland Dove, a replica of a seventeenth-century English trading ship that accompanied Lord Baltimore’s original expedition to Maryland, is moored. The jug has two lions-passant applied sprigs flanking an armorial crest (fig. 20) that might be that of a Roman Catholic cardinal. Careful examination of the fragment allowed us to decipher a date of 1646.

A quick search through standard sources on Westerwald stoneware came up with a very convincing parallel in the form of a complete jug with the date 1648.[19] The central medallion crest is different than our specimen, but the style and execution are quite similar. Subsequent examination of additional fragments of Westerwald stoneware in the collection has led to the identification of other specimens that have the same flanking lion motif. Many of these specimens are quite small and are identifiable only because we have seen the complete decoration on the large fragment.

In the early 1990s, while developing the installation of an exhibit that featured artifacts from the two Chesapeake colonial capitals, St. Mary’s City and Jamestown, we decided to include a reproduction of a Dutch genre painting as part of a display on early taverns or ordinaries in the colonial Chesapeake. The original painting, owned by the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, is entitled The Barroom and was painted in 1665 by Abraham Diepraam (fig. 21). It depicts the interior of a seventeenth-century tavern, and sitting on the floor by a chair is an identical jug to the one whose fragments we had found in St. Mary’s.

Matched Tin-Glazed Drinking Bowls

Pottery vessels found in seventeenth-century archaeological contexts are seldom seen as sets or matched specimens. A notable exception are the small tin-glazed bowls illustrated in figures 22 and 23. Painted in multiple hues of blue with black outlining and detailing, these vessels are thought to be small drinking bowls; the capacity of each is slightly more than one cup. The blue decoration represents a floral panel motif—possibly large peonies and alternating floral sprays—that repeats around the vessel. The black outlining is known in Holland as trekking (“drawing”). Inside each vessel is a black line indicating a fill level for the bowl. Both vessels have well-formed, relatively tall footrings.

These rare matching bowls were excavated at the important St. John’s site, which had been first occupied in 1638 as a tobacco planter’s home and later was used as a place where the general assembly met and Maryland’s official records were kept. Later in the seventeenth century, the site was used as a home and tavern. Stylistically, the Dutch bowls date to the last quarter of the seventeenth century or the very early eighteenth century. Unfortunately, they were found in redeposited fill within a cellar hole, so deposition dates do not help us tie down the period of use.

Punch consumption was rather common in early Maryland, based on its mention in seventeenth-century pricing lists passed by the general assembly to regulate ordinaries in the colony. Most of these price lists mention both “Rum Punch” and “Brandy Punch” to further describe the libation.[20]

Ottoman-Period Pottery

Beginning in the sixteenth century and through the eighteenth, Kütahya was the center of ceramic production in Turkey, succeeding Iznik (formerly Nicaea). Iznik is located between Kütahya and Istanbul and had served as the principal production site for highly decorated Turkish ceramics in the preceding centuries. Both Iznik and Kütahya were well known for their decorative tiles in addition to their ceramic vessels. Produced by Armenian Christians, these brightly decorated ceramics in a range of rich colors were shipped throughout the Islamic world and imported into Europe.

Eighteenth-century Turkish ceramics have been identified on only four other archaeological sites in North America—two in Williamsburg, Virginia, and two in Nova Scotia, Canada.[21] The Williamsburg examples came from Raleigh Tavern and Weatherburn’s Tavern, and the Canadian examples are from Fortress Louisburg and Canso on Cape Breton.

Our specimen was discovered at Garrett Van Sweringen’s Inn in St. Mary’s City (fig. 24). Van Sweringen operated a private lodging house in St. Mary’s City, and according to his will dated 1698 his holdings included a building referred to as a “coffee house” (fig. 25). The Canadian and Williamsburg examples clearly date to the eighteenth century, whereas our example may date to either the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century. The number of fragments recovered at Van Sweringen’s Inn suggests that more than one vessel was present.

Atlantic Lunch Bowl

The ceramic bowl illustrated in figure 26 was discovered in 1972 during excavations at the Tolle-Tabbs site, on the outskirts of St. Mary’s City. Made of highly vitreous “stone china,” the bowl is inscribed “Atlantic / Lunch” on the interior rim and the bottom bears the maker’s mark of Carr China (Grafton, West Virginia) and the description “Hotel Dept.” The bowl was the focus of an intense oral history project in the early 1970s by George L. Miller, leading to the publication in 1984 of a celebrated article entitled “Ode to a Lunch Bowl.”[22]

The Atlantic Lunch was a restaurant in the basement of the Atlantic Hotel in Washington, D.C. (fig. 27). It was operated by the Carroll family, who had deep connections to St. Mary’s County during the early twentieth century. Miller’s research revealed that the lunchroom served as a principal nexus and link to southern Maryland for individuals who went to the city for work and “functioned as an outpost for St. Mary’s County for over half a century.”[23] Family descendants have come to see this rather obscure artifact, which illustrates how a humble object can remind us of how a sense of community extended beyond the geographic boundaries of early-twentieth-century St. Mary’s County.

Timothy B. Riordan, The Plundering Time: Maryland and the English Civil War, 1645–1646 (Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 2003), passim.

Gisela Reineking-von Bock, Steinzeug: Kunstgewerbemuseum der Stadt Köln, Kataloge des Kunstgewerbemuseums Köln 4 (Cologne: J. P. Bachem, 1971), fig. 565.

John Hicks was the eighteenth-century owner of the land that seventeenth-century St. Mary’s City occupied.

Henry M. Miller et al., A Search for the “City of Saint Maries”: Report on the 1981 Excavations in St. Mary’s City, Maryland, St. Mary’s City Archaeology Series 1 (St. Mary’s City, Md.: Historic St. Mary’s City Commission, 1983); and Henry M. Miller et al., A Summary on the 1981–1984 Archaeological Excavations in St. Mary’s City, Maryland, St. Mary’s City Archaeology Series 2 (St. Mary’s City, Md.: Historic St. Mary’s City Commission, 1986).

Reineking-von Bock, Steinzeug, figs. 514, 517, 518, and 519.

Henry Chandlee Forman, “Some Pioneering Excavations in Virginia and Maryland,” Maryland Archeology 22, no. 2 (1986): 10, 11.

Anne Dowling Grulich, Façon de Venise Drinking Vessels on the Chesapeake Frontier: Examples from St. Mary’s City, Maryland, Historic St. Mary’s City Research Series 7 (St. Mary’s City, Md.: Historic St. Mary’s City, 2004), pp. 16, 17.

Forman, “Some Pioneering Excavations in Virginia and Maryland.”

Richard Coleman-Smith and Terry Pearson, Excavations in the Donyatt Potteries (Chichester, U.K.: Phillimore, 1988).

Richard Coleman-Smith, R. Taft Kiser, and Michael J. Hughes, “Donyatt-Type Pottery in 17th- and 18th-Century Virginia and Maryland,” Post-Medieval Archaeology 39, no. 2 (2005): 294–310.

Merry Abbitt Outlaw, “Scratched in Clay: Seventeenth-Century North Devon Slipware at Jamestown, Virginia,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), pp. 17–38.

Silas D. Hurry, “What Is ‘What’ in St. Mary’s City?” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2005), pp. 220–22.

Louis L. Lipski and Michael Archer, Dated English Delftware: Tin-Glazed Earthenware, 1600–1800 (London: Philip Wilson for Sotheby Publications; New York: Harper & Row, 1984).

Cary Carson, Ronald Hoffman, and Peter J. Albert, eds., Of Consuming Interests: The Style of Life in the Eighteenth Century (Charlottesville: Published for the United States Capitol Historical Society by the University Press of Virginia, 1994).

Transcription of Robert Slye’s Probate Inventory, ms. on file, Historic St. Mary’s City, Maryland, n.d.

William M. Kelso and Edward A. Chappell, “Excavation of a Seventeenth Century Pottery Kiln at Glebe Harbor, Westmoreland County, Virginia,” Historical Archaeology 8 (1974): 53–63.

Beverly Straube, “The Colonial Potters of Tidewater Virginia,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 21, no. 2 (Winter 1995): 24–27.

Jacqueline Pearce, Post-Medieval Pottery in London, 1500–1700, Volume 1: Border Wares (London: HMSO, 1992).

Reineking-von Bock, Steinzeug, fig. 567.

Archives of Maryland Online, “Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly, October 1678–November 1683, http://aomol.msa.maryland.gov/000001/000007/html/index.html (accessed February 14, 2017).

Audrey Noël Hume, Food, Colonial Williamsburg Archaeological Series 9 (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1978); Denise Hansen, Eighteenth Century Fine Earthenwares from Grassy Island, Research Bulletin 247 (Ottawa: Environment Canada, Parks, 1986); Heidi Moses, Parks Canada, personal communication, August 2, 2005; and Lynda Carroll, “Could’ve Been a Contender: The Making and Breaking of ‘China’ in the Ottoman Empire,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 3, no. 3 (September 1999): 177–90.

George L. Miller, “Ode to a Lunch Bowl: The Atlantic Lunch as an Interface Between St. Mary’s County, Maryland, and Washington, D.C.,” Northeast Historical Archaeology 13, no. 1 (1984): 2–8.

Ibid., p. 6.