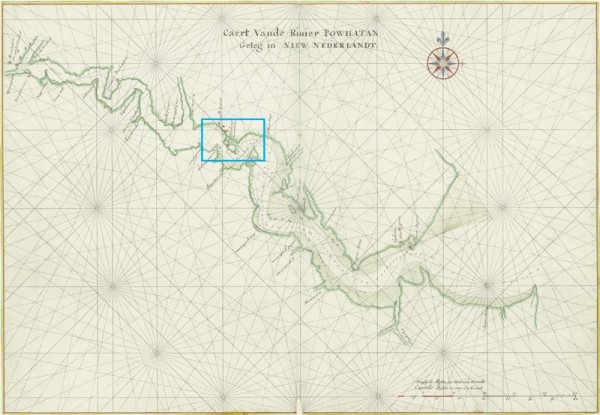

Johannes Vingboons (ca. 1616–1670), Caert Vande Riuier POWHATAN. Geleg in NIEW NEDERLANDT, [1617]. (Kaarten and Tekeningen, Maps and Plans Division, document 4. VELH 619.89, Algemmeen Rijksarchief, The Hague.) This map is believed to be a Dutch copy of an English original drawn in 1617. Michael Jarvis and Jeroen van Driel, “The Vingboons Chart of the James River, Virginia, circa 1617,” The William and Mary Quarterly 54, no. 2 (1997): 377–94.

Detail of the map illustrated in fig. 1 showing Jamestown Island.

Conjectural depiction of James Fort ca. 1608, based on the archaeological evidence. (Courtesy, National Geographic Society.)

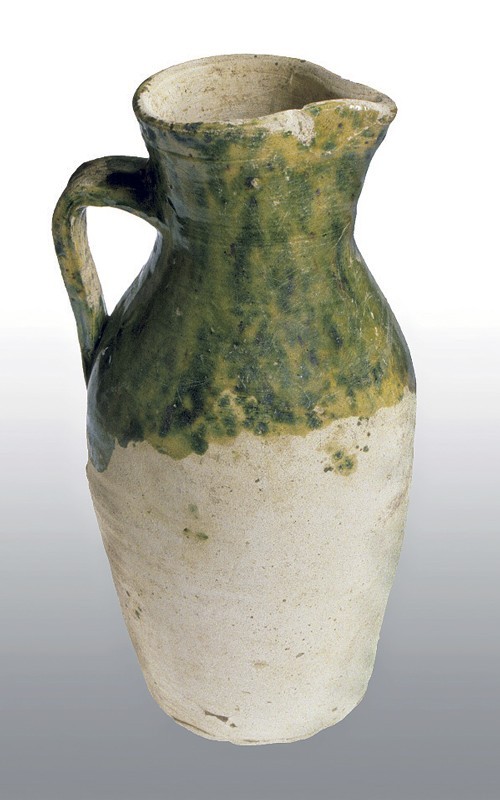

Drinking jug, Surrey-Hampshire, England, ca. 1600–1610. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 7 1/2". (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation, 688-JR.) These ceramics types are generally referred to in America as Border Ware, but in Britain this would be confused with ceramics from the Scottish borders.

Archaeologist excavating a drinking jug from James Fort’s bulwark trench, ca. 1610. (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation.)

Crucibles, Hesse, Germany, ca. 1608. Refractory clay. H. of bottom crucible 3 1/2". (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation, 151-JR.)

Bartmann jug medallion, Frechen, Germany, dated 1604. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation, 7913-JR.)

Mask of Bartmann jug found while water-screening materials from the ca. 1611–1617 well. (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation.)

Bartmann jug, Frechen, Germany, dated 1604. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Pedestal cup, Germany, ca. 1590–1617. Lead-glazed earthenware with slip decoration. H. 3 1/2". (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation, 6655-JR.)

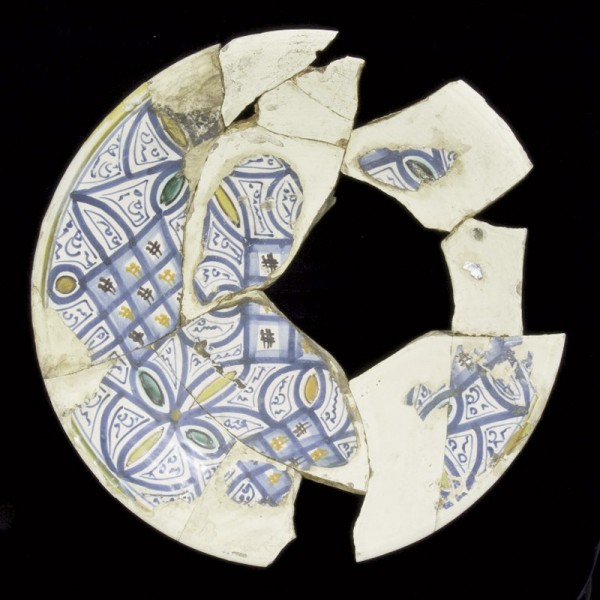

Dish, Montelupo, Italy, ca. 1580–1617. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Jamestown Foundation, 7919-JR.)

Dish, Montelupo, Italy, ca. 1580–1620. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 12 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Escudilla, Muel, Spain, ca. 1607–1610. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 1 3/4"; D. of bowl 4 1/2". (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation, 7944-JR.)

Escudilla, Muel, Spain, ca. 1600–1610. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Escudilla, Barcelona, Spain, ca. 1590–1610. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 4 7/8". (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation, 7417-JR.)

Pitcher, Portugal, ca. 1617–1624. Burnished earthenware. H 10 3/4". (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation, 2005-JR.)

Bowl fragment, Zhangzhou, China, ca. 1572–1620. Slip-decorated porcelain. (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation.) Mended section of one of two slip-decorated Chinese porcelain vessels found in disturbed contexts of James Fort.

Censer, Zhangzhou, China, ca. 1572–1620. Slip-decorated porcelain. (Courtesy, HIP / Art Resource, NY.)

Archaic mark on the Jamestown bowl base fragment (7915-JR) suggesting that the vessels were made in Jingdezhen. D. of footring 2".

Drinking cup, Essex, England, ca. 1610. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation, JR2718W-2158H.)

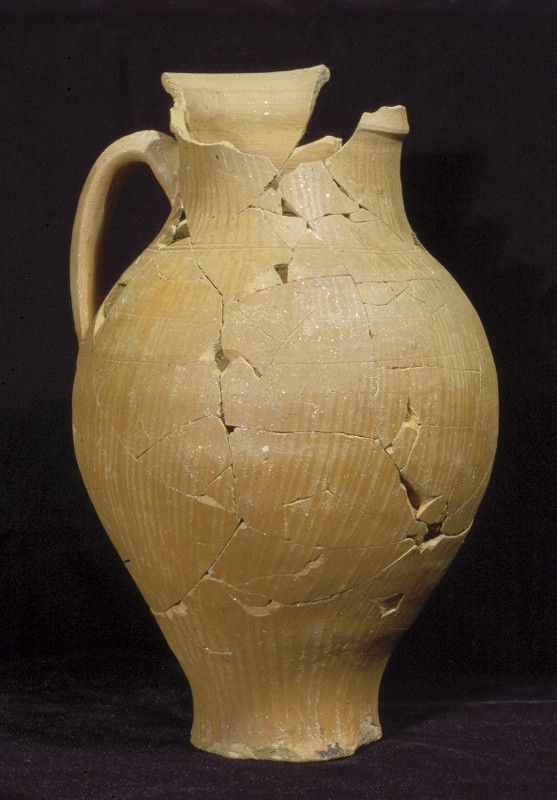

Storage jar, South Somerset, England, ca. 1610. Slip-decorated, lead-glazed earthenware. H. 14 3/4". (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation, 5212-JR.) This jar might have been made in the pottery kilns of Donyatt.

“There never was an Englishman left in a foreign country in such misery as we were in this new-discovered Virginia.”[1] This lament by colonist George Percy encapsulates the early years of the Jamestown settlement that in 1607 established England’s first permanent toehold on the banks of the James River in North America (figs. 1, 2). The historical records of the nascent colony are replete with accounts of privation and death from starvation, inadequate shelter, diseases, and warfare with the Virginia Indians. Archaeological investigation since 1994 of James Fort—the initial settlement sponsored by the joint-stock Virginia Company of London—has found in the ground evidence of the adversities faced by the colonists. These most notably include the skeletal remains of a victim of the survival cannibalism documented as occurring in the winter of 1609.[2]

Initially, the split-timber palisade enclosing one acre of land contained mud-and-stud barracks housing, rudimentary pit houses, storehouses, a church, and wells. Even early casualties were buried within the fort’s walls to hide the loss of men from the Indians. Using the archaeological evidence in combination with the historical record, a realistic image of the fort can be developed for the first time (fig. 3). Life was hard and uncertain, with conditions improving only slightly throughout the years that the Virginia Company held control of the colony (1607–1624).

Within this muddy, miserable milieu an unexpected, divergent narrative is told by the material culture. Unearthed from features of the fort dating to the Virginia Company period, many of the objects, and particularly the ceramics, are unusual for most contemporary English contexts. The ceramics represent wares from Asia and Europe that were not readily accessible to English consumers, as well as high-status examples of English wares that are rarely found archaeologically in England.[3]

The incongruous picture of life in the isolated settlement can be explained by the elite status of many of the early colonists, the importance of material culture in Jacobean English society to signal that status, and the access to exotic goods enjoyed by the sea captains and other mariners who sailed in and out of the Virginia entrepôt. Some colonists, it seems, were able to surround themselves with the types of wares that would signal their elevated status to the fort community of gentlemen, craftsmen, specialists, and laborers.

George Percy, who made the complaint at the beginning of this essay, was one of the privileged gentlemen counted among the colony’s elite. As the eighth son of the eighth Earl of Northumberland, Percy was “the highest-born gentleman of the settlement” at the time of his arrival and served as the colony’s leader from September 1609 to May 1610 and then briefly in 1611.[4] While resident in the colony, Percy received a steady stream of supplies from his brother in London, Henry Percy the ninth Earl of Northumberland. Among the many “necessaries” sent to Virginia were elements of arms and armor (some “hatched with goulde”), “diverse sewts” of clothing, gold buttons and lace, a feather bed with “a Coveringe of tapestrie,” twelve pairs of shoes and six pairs of boots. Foodstuffs were also shipped to fulfill Percy’s stated obligation as governor “to keep a continuall and dayly Table for Gentlemen of fashion,” while the other settlers had to make do with the daily allowance out of the Company store of “a pound of meale a day and a little Oatmeale” per person. Even “readie money” was delivered so Percy would not be caught short in case his credit was not honored by visiting seafarers with commodities to sell, such as the “Tobacco and other Commodities” he purchased from mariner Robert Markam, who likely had just come from the West Indies.[5]

Percy’s visibly elevated status represented the position held to some degree by most of the colony’s gentlemen, especially if they were also shareholders in the joint-stock Virginia Company. With their extraordinary privileges, the colony’s gentlemen could not only eat better than the rest, they could also embellish their wilderness setting with the material culture of the English gentry. Freed by their distance from England of the normal regulatory controls, the upper echelon of the Jamestown society could also afford themselves of material luxuries that were made accessible by visiting Dutch merchant ships as well as by the English supply ships arriving by way of the Caribbean.

Jamestown Island’s 1,500 acres have yielded hundreds of thousands of ceramic sherds and vessels among the more than three million artifacts recovered since archaeological investigations began in the waning years of the nineteenth century. Cooperatively managed by the National Park Service (NPS) and Preservation Virginia (PV), the island’s western end held the 1607 English settlement of James Fort that expanded eastward into New Town in the 1620s. Jamestown served as the colony’s capital through the seventeenth century, and most of the ceramics date to that era. Reflecting a time before restrictive English mercantile policies and before English ceramics came to dominate American households, the Jamestown ceramic collection from NPS and PV excavations includes a cosmopolitan array of pottery and porcelain from Europe and Asia. The culturally diverse material culture of seventeenth-century Virginia was tied together by a global network “so that even an Englishman in the Virginia wilderness could eat Spanish raisins from Italian dishes, drink his water from French flasks, and pour German wine from Belgian jugs into Chinese cups.”[6]

Surrey-Hampshire Border Ware Drinking Jug

One of the biggest disappointments for the early Jamestown colonists was the realization that once they had consumed all their stores of beer, aqua vita, and sack there would be nothing but water to drink. The colonists attempted to make their own beer from the start but found that Virginia’s extreme heat spoiled their malted grains. The lucky ones with money or goods of value could trade for the beer that was a standard provision aboard each arriving ship. Captain John Smith observed that the mariners on these “floating taverns” would readily pilfer the stores of beer and food intended for their return voyages “to sell, give or exchange with us for money, Saxefras, furres, or love.”[7]

The spouted jug illustrated in figure 4 is a Surrey-Hampshire Border Ware drinking vessel associated with beer. Found intact among slaggy waste from glassmaking trials in the fort’s bulwark trench, it was probably lost sometime between 1608 and 1610 (fig. 5). Another complete drinking jug in this ware was recovered from the Sea Venture that had been sailing to Virginia in 1609 when it shipwrecked in Bermuda. Many of these vessels were excavated from late-sixteenth- and early-seventeenth-century contexts at the Inns of Court in London, which maintained detailed accounts in which bulk orders for “beer pottes” from the potteries situated along the borders of Surrey and Hampshire counties in England were frequently mentioned. These “green pots” frequently had to be replaced as a result of theft and breakage, the latter often from students expressing displeasure at their professors.[8]

Hessian Crucibles

While researching in the National Park Service (NPS) collections at Jamestown in the late 1980s, the renowned archaeologist Ivor Noël Hume made a prophetic discovery. In a box marked “found near the Pocahontas monument” he noticed the joined Hessian crucibles illustrated in figure 6, which, in his opinion, indicated the location of the long-lost James Fort.[9] The crucibles had been unearthed on property belonging to the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (APVA; now Preservation Virginia) during utility work in 1938, and as archaeologists discovered almost sixty years later, the Pocahontas statue had unwittingly once stood in the midst of the English fort.[10]

The two beaker-shaped refractory clay vessels were luted together with a clay wrap to create a sealed environment for an industrial process, and then cracked open on one side to remove the contents. Remnants of molten glass still adhere to the interior surfaces.[11] Although the crucibles were from a disturbed context, they mended with a sherd found in 1995 by Preservation Virginia archaeologists in a sealed fort context dated to 1610 (Pit 1).[12] This early date and the small size of the crucibles indicate the “tryal of glasse” by German glassmakers sent to the colony in 1608 by the Virginia Company.[13] Analysis using SEM-EDS of a sample of Jamestown crucible fragments revealed that the vessels were produced in the Hessian region of Germany.[14] The investment in Hessian industrial wares, which were considered the very best throughout the seventeenth century, shows the importance the Virginia Company placed on the pursuit of glassmaking in the New World.

Frechen Bartmann Jug

One of the most common vessel forms in the early James Fort contexts are the salt-glazed stoneware jugs made in Frechen, Germany. Jamestown is not unique in this ceramic preference. Frechen stoneware is commonly found in seventeenth-century contexts of colonial America and on shipwrecks from the period. It has been estimated that it was the most widely traded German ceramic, with ten million vessels imported through London in the early seventeenth century.[15] England had not yet developed stoneware or glass bottle industries, and these robust vessels were the most satisfactory containers for storing and shipping liquids, particularly beer and wine.

The Frechen jug represented by the fragments in figures 7 and 8 was at one time quite magnificent. Known as a Bartmann (“bearded man”) jug or Bellarmine, it is adorned on the neck with the face of a bearded man. In addition, the jug once had three large medallions on its body, like the parallel intact vessel in figure 9. The medallions depict a crowned double-headed eagle, an ancient symbol that was adopted as the heraldic emblem of the Germanic Holy Roman Empire. From 962 until 1806 German kings ruled the empire, of which the pope was the spiritual head. By the time of the Jamestown settlement, the position of emperor was dominated by the Catholic dynasty of Austrian Habsburgs. The James Fort jug, advertising political loyalty with the Spanish-Habsburg dominion, was found in a fort well dating circa 1611–1617. It most assuredly was owned by one of the fort’s gentlemen who identified with the status and power represented by the medallion despite abounding Catholic-Protestant rivalries. This conflicted sentiment was expressed by Jamestown colonist Edward Maria Wingfield in 1608 when he admitted that he “always admired any noble vertue & prowess, as well in the Spaniards” but added that he “always distrusted and disliked their neighborhoode.”[16] It is interesting to note that the jug bears the date 1604, the year that confirmed pacifist King James I negotiated the end of the nineteen-year Anglo-Spanish war with the Treaty of London.

Weser Slipware Pedestal Cup

When a Weser slipware two-handle pot was found in Hampton in the late 1960s (Robert Hunter, “Hampton, Virginia,” fig. 7, in this volume), it was only the second example of the German ware identified from a Virginia colonial site. The other was a dish sherd from the Chesopean site in Virginia Beach.[17] It would take another forty years before excavations of James Fort would uncover a few more examples. Even so, the pedestal cup illustrated in figure 10 is unique because all of the other Weser ware sherds from Jamestown are from dishes.[18] The diminutive cup is also rare in the corpus of known products from the Weser kilns.[19] It must have had a specialized purpose, but for now that remains unknown.

The cup was found in a fort cellar that had been backfilled in 1617. The cellar was adjacent to two row houses constructed in 1611 as residences for the colony’s governor and his councillors, suggesting that the vessel was a discard from one of those high-status households.

Weser ware was made in kiln sites all along the Weser River, which was the route to Bremen for export. Until about 1620 most of the light-bodied ware went to the Netherlands, and was redistributed by Dutch traders throughout Europe. The Weser ware in Britain is believed to be a result of this commerce.[20] In America the ware is rare and is believed to be part of the Dutch trade as well. The Dutch were particularly active in Virginia from the first quarter of the seventeenth century, and even established permanent trading posts along the waterways to expedite commerce with the English settlers for tobacco. In addition to the three Virginia sites, Weser ware has been found on two circa 1600–1620 Iroquois sites in New York State that also contained a large number of trade goods typically carried by the Dutch.[21]

Montelupo Dish

The polychrome dish shown in figure 11 was found in the same fort cellar as the Weser slipware pedestal cup and, like the cup, probably was a “display ware” belonging to one of the colony’s gentlemen. Hand-painted with a lozenge net design inspired by Islamic influences, this tin-glazed earthenware known as maiolica was made in Montelupo, Italy.[22] Located between Pisa and Florence, Montelupo was the source of most of the Italian imports into England in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.[23]

Even though the Jamestown dish is a singular find from a colonial American context, variations of the lozenge net design are the most common motifs found on Montelupo wares in the British Isles during the early modern period (fig. 12). The similarly decorated dishes, although few in number, have wide distribution in Britain, including Bristol, Canterbury, Devon, London, Somerset, east Yorkshire, Ireland, and even a circa 1600 Spanish shipwreck off the coast of Scotland.[24] The latter is possibly the result of an early-seventeenth-century agreement between Manises in Valencia, Spain, and Pisa in Tuscany, Italy (the port of export for Montelupo) to deal in each other’s pottery.[25]

From the sixteenth century onward, maiolica from Montelupo was considered fine enough to be suitable for diplomatic gifts and wealthy patrons, challenging the dominance held by Spanish lustreware in the previous century. One of Jamestown’s elite—possibly Lord De La Warr, who arrived in 1610 as the colony’s new governor and the wealthiest man to set foot in the settlement—was a participant in the new consumerism that saw value in objects not only for the materials from which they were made but for their rarity and novelty.

Spanish Lustreware Escudilla

The iridescent metallic decoration on the small tin-glazed earthenware bowl (escudilla) in figure 13 is from the addition of copper oxides.[26] Known as lustreware, this type of Hispano-Moresque pottery was produced in Spain between the twelfth and eighteenth centuries. Many of the designs reflect Islamic motifs from the influence of immigrant Persian potters who, since the eighth century, had been making lustrewares in response to the Quran’s prohibition against the use of gold and silver table services.[27]

Escudilla means “bowl,” often one with two handles; like the English porringer, it was used for soups, broths, and pottages. This escudilla was found in a James Fort well dating circa 1608–1610. The motifs of wading bird and split flowers (flores partidas) are typical of the Morisco potters working in the Aragon town of Muel (fig. 14). Moriscos were former Muslims of Arab North African descent who worked under the protection of upper-class patrons.[28] This protection ceased, as did the pottery production, when the Moriscos were officially expelled from Muel in 1610. Neutron Activation Analysis (NAA) of the James Fort escudilla confirmed that it was from Muel, making it the first recognized vessel from that town in North America.[29]

A second escudilla (fig. 15) found in the same context is decorated on the interior base with a pinwheel design (rodavientos). This design is typical of the motifs used by Catalan potters, and that attribution has been confirmed by NAA.[30] These wares are rare in Britain except in mariner communities, such as Limehouse in London, or in merchant areas of port cities.[31] In the New World, the largest collection of Spanish lustreware has been found in Santo Domingo; the ware is otherwise known in Florida, Newfoundland, and Jamestown, where it is thought to be the result of individual trade and not one controlled by merchants.[32]

Portuguese Merida-Type Pitcher

When the earthenware pitcher illustrated in figure 16 was discovered at the bottom of a brick-lined James Fort well, the archaeologists were reluctant to accept the curatorial assessment that placed its context within the second decade of settlement. They were searching for the fort’s western palisade wall, and when the well was located, they were convinced that it was the 1608 well that had been documented as having been dug in the fort by the colonists. It was only after further excavation revealed the well lay outside the fort’s perimeter that the research team was in accord.[33] The subsequent discoveries of a parallel pitcher on a 1622 Spanish shipwreck off the Florida coast and a similar vessel located in the post-1618 settlement of Renews, Newfoundland, further confirmed the original curatorial assessment.[34]

While commonly known as “Merida-type ware” since the 1960s, this is a misnomer because Merida lies in Spain and chemical analysis of the clays has shown that this red-bodied micaceous ware was made in Portugal. The major production centers are considered to be Lisbon, Aveiro, and Coimbra, although further research is required to refine the data.[35]

Portuguese redwares are not common in Jamestown contexts and, besides the pitcher, are represented by shallow bowls, costrels, and olive jars. They do not occur in the settlement’s earliest contexts but start appearing with assemblages that include Portuguese tin-glazed wares and North Italian wares—ceramics believed to have been transported to the colony by Dutch merchants beginning in the 1620s. The unglazed Portuguese pitchers, used to serve water and to keep it cool, were noted for maintaining water with “excellent smell and taste of the clay.”[36] This might help to explain the vessel’s appearance in Jamestown, where the English colonists often had to rely on water rather than their customary alcoholic beverages.

Slip-Decorated Chinese Porcelain Saucer and Bowl

Thirty-one sherds of two unique Chinese porcelain vessels—possibly a saucer and a bowl—have been found scattered in several disturbed contexts of James Fort (fig. 17). The vessels are unusual in that the exterior decoration consists of white-slipped designs over a deep blue ground. The thick white porcelain clay slip depicting the traditionally Chinese design of dragons in pursuit of a flaming pearl is further embellished with incised or sgraffito decoration. The interior surfaces are undecorated.

Initially it was thought that these vessels were made in the provincial kilns of Zhangzhou in the province of Fujian. Until recently, porcelain from this area was commonly known in the West as Swatow for Shantou, the port in Guangdong province believed to be exporting the ware.[37] The Jamestown sherds are very similar to a Zhangzhou censer in the Museum of East Asian Art in Bath, England (fig. 18).[38] Then the bowl base was found, which bears an archaic Chinese mark associated with special and important vessels of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries (fig. 19). The mark reads “yu tang jia qi” (“exquisite vessel from jade hall”), an imaginary beautiful place and the preeminent scholarly institution of the inner court. This type of underglaze blue basal mark is generally found on wares made in private (i.e., non-imperial) kilns in Jingdezhen. No vessels from Zhangzhou kilns have been documented with this mark, although archaeological research in this area is very preliminary.[39] For now, these blue-and-white slip-decorated porcelain vessels from James Fort remain unique finds in colonial America.

Essex Black-Glazed Ware, Double-Handled Cup

In the early seventeenth century, London’s utilitarian wares were provided mainly from Harlow in west Essex, Woolwich and Deptford in London, and from the potteries along the border between Surrey and Hampshire counties. Since the early Jamestown colony was provisioned by London merchants, it is not surprising that vessels from these three areas are common in the fort excavations. What is surprising is the number of unusual vessel forms from these production areas that were recovered from the early Jamestown contexts. The Essex black-glazed ware, double-handled cup found in the circa 1608–1610 James Fort well is an example (fig. 20).

Essex black wares are composed of a red-bodied iron-rich clay that is covered with a lustrous interior and exterior black glaze. Scientific analysis of the glaze suggests that it was created by adding brass-derived copper to a lead glaze, which in turn interacted with the iron-rich fabric.[40] Cylindrical and flared mugs—known as tygs—are the most common black-ware forms and are thought to have been influenced by tin-glazed earthenware, German stoneware, and contemporary metal forms. The mugs are typified by cordoning just below the rim and above the base.[41]

The double-handled cup from the well exhibits both the characteristic glossy black glaze and top and bottom cordoning of the Essex drinking vessels, but is unusual in that it also has a rounded bunghole near the base on one side. Bung-hole jars or cisterns are common in the Harlow repertoire but these are much larger plain, lead-glazed earthenwares. No parallel has been discovered thus far for the Jamestown cup, but it has been suggested that it could be an early form of a specialized vessel known as a posset pot.[42] It does not have the typical integral spout of most posset pots,[43] but the two-handled vessel reflects the shape of these pots, which were used to sip a whey-alcohol mixture from the bottom of a spiced and curdled milky drink, often used medicinally to treat colds and other illnesses. The bung hole could have been supplied with a spout of another material to serve this purpose.

South Somerset Storage Jar

Wares made in the southwestern region of England, such as this large jar (fig. 21) found in the same fort well as the previous vessel, are rare in the early Jamestown contexts. The Virginia Company of London was in control of the colony from 1607 to 1624, and pottery supplied by London-area merchants predominates the similarly dated archaeological assemblages. Many of these merchants were investors in the company and hoped to profit not only by the resources found and developed in Virginia, but also by supplying the settlement. Once the company was dissolved, commercial involvement with Virginia required investing in plantation development, which most London merchants were loath to undertake, and their monopoly on trade was relaxed.[44]

Rather than representing a regular source of supply, the early context of the jar suggests that it is the result of a June 1609 stopover in Plymouth, Devon, made by Virginia-bound ships from London. A fleet of nine vessels assembled in Plymouth to coincide with the arrival, from Lyme Regis, of Sir George Somers, the newly appointed Admiral of Virginia. The fleet also took on “some necessaries,” as some provisions could be acquired more cheaply outside of London.[45]

The storage jar was presumably a provisioning container for a comestible purchased in Plymouth. It had been wheel-thrown in two parts, with the join covered on the exterior by a strip of thumb-impressed clay. A similar strip reinforces the rim exterior. The pot is glazed on the interior and on the exterior shoulder with an olive-green lead glaze. Under the exterior glaze is a band of white slip through which a series of finger-wiped wet sgraffito arcs. A similar jar was found in a 1620–1622 context in a settlement adjacent to Jamestown and in excavations of a kiln dating to the first half of the seventeenth century in Donyatt, Somerset.[46].

George Percy, “Observations Gathered Out of a Discourse of the Plantation of the Southern Colony in Virginia by the English, 1606. Written by that Honorable Gentleman, Master George Percy,” in The Genesis of the United States: A Narrative of the Movement in England, 1605–1616 . . . , edited by Alexander Brown, 2 vols. (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1890), 1:167.

James Horn, William, Douglas Owsley, and Beverly Straube, Jane: Starvation, Cannibalism, and Endurance at Jamestown (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and Preservation Virginia, 2013).

Beverly A. Straube, “European Ceramics in the New World: The Jamestown Example,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 47–71; Beverly A. Straube and Jacqueline Pearce, “The Double Dish Dilemma,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 215–17; Beverly A. Straube, “A Peacock’s Flight . . . across 100 Years,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), pp. 199–201; Beverly A. Straube, “The Prodigal Son Returns to Jamestown,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2003), 262–65; Beverly A. Straube, “This Little Piggy Went to Virginia,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2005), pp. 217–19; Beverly A. Straube, “A Roman Oil Lamp Illuminates 17th-Century Jamestown,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2008), pp. 279–83; Beverly A. Straube, “‘Captain John Smith’s Pots’: A Brief Survey of the First English Pottery Brought to Jamestown, Virginia,” in Amanda Dunsmore, ed., This Blessed Plot, This Earth: English Pottery Studies in Honour of Jonathan Horne (London: Paul Holberton, 2011), pp. 159–71.

John W. Shirley, “George Percy at Jamestown 1607–1612,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 57, no. 3 (1949): 226–43.

Ibid., pp. 235–39.

Taft Kiser, “The Ceramics Missed by the Muster: Jordan/Farrar,” paper presented at the Society for Historical Archaeology Conference in Vancouver, British Columbia, January 1994.

John Smith, “The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Iles . . . ,” in Phillip L. Barbour, ed., The Complete Works of Captain John Smith (1580–1631), facsimile ed., 3 vols. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, Va., 1986), 2:143.

L. G. Matthews and H.J.M. Green, “Post-Medieval Pottery of the Inns of Court,” Post-Medieval Archaeology 3, no. 1 (1969): 1–17.

Ivor Noël Hume, The Virginia Adventure: Roanoke to James Towne, an Archaeological and Historical Odyssey (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), p. 428.

In 1893 the APVA had acquired 22 1/2 acres of Jamestown Island.

Chemical analysis of the glass revealed that it was compositionally distinct from typical potash glass (Waldglas) produced in Germany. The difference is interpreted as adaptive measures of the glassmakers in light of scarce resources. J. Victor Owen, John D. Greenough, and Beverly Straube, “Compositional Characteristics of Jamestown ‘Tryal’ Glass (Virginia, ca. 1608),” Historical Archaeology 48, no. 4 (2014): 76–94.

Beverly Straube and Nicholas Luccketti, 1995 Interim Report on the APVA Excavations at Jamestown, Virginia (Richmond, Va.: Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, 1996), pp. 22–23.

Glass was normally produced in large refractory-clay siege pots, 10–16 1/2 inches in height that could hold between 65 and 145 pounds of the melted glass batch. J. C. Harrington, A Tryal of Glasse: The Story of Glassmaking at Jamestown (1952; reprint, Richmond, Va.: Dietz Press, 1972). Small crucibles were used for working with precious metals and for experimentation.

Marcos Martinón-Torres and Thilo Rehren, “Analysis and Interpretation of Some Crucible Fragments from Jamestown,” unpublished manuscript on file at the Jamestown Rediscovery Center, Historic Jamestown, Virginia.

David Gaimster, German Stoneware, 1200–1900: Archaeology and Cultural History (London: British Museum Press, 1997).

Edward Maria Wingfield, “A Discourse of Virginia,” 1608, Lambeth Palace Library, MS 250, fols. 382–95 (cited in Phillip L. Barbour, ed., The Jamestown Voyages Under the First Charter, 1606–1609, 2 vols. [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press for the Hakluyt Society, 1969], 1:229).

The Chesopean site was excavated in 1955 by avocational archaeologist Floyd Painter.

Since 1994, the Jamestown Rediscovery Project has recovered only thirty-nine sherds of Weser ware, all from hammer-headed dishes, and some probably belonging to the same vessel. Personal communication with Merry Outlaw, 2016.

Personal communication with Hans Georg-Stephan, 2006.

John G. Hurst and David Gaimster, “Werra Ware in Britain, Ireland and North America,” Post-Medieval Archaeology 39, no. 2 (2005): 278.

James W. Bradley and Monte Bennett, “Two Occurrences of Weser Slipware from Early 17th Century Iroquois Sites in New York State,” Post-Medieval Archaeology 18, no. 1 (1984): 301–4.

There are sixteenth-century Iranian lusterware bowls and dishes with the same decorative motif. Fausto Berti, Il Museo della Ceramica di Montelupo / The Ceramics Museum of Montelupo (Florence, Italy: Polistampa, 2008), p. 334.

John G. Hurst, “Italian Pottery Imported into Britain and Ireland,” in Timothy Wilson, ed., Italian Renaissance Pottery: Papers Written in Association with a Colloquium at the British Museum (London: Published for the Trustees of the British Museum by British Museum Press, 1991), pp. 212–31.

Cynthia Gaskell Brown, ed., Castle Street: The Pottery, Plymouth Museum Archaeological Series 1 (Plymouth, Eng.: Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery, 1979); Duncan H. Brown and Celia Curnow, “A Ceramic Assemblage from the Seabed near Kinlochbervie, Scotland, UK,” International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 33, no. 1 (April 2004): 29–53; Hurst, “Italian Pottery Imported into Britain and Ireland,” pp. 212–31; K. J. Barton, “The Excavation of a Medieval Bastion at St. Nicholas’s Almshouses, King Street, Bristol,” Medieval Archaeology 8, no. 1 (1964): 184–212; Hugo Blake, “Italian Wares,” in Roberta Gilchrist and Cheryl Green, eds., Glastonbury Abbey: Archaeological Investigations, 1904–79 (London: Society of Antiquaries, 2015), pp. 269–70.

Brown and Curnow, “A Ceramic Assemblage,” p. 45 (citing Gaetano Guasti, Di Cafaggiolo e d’altre fabbriche di ceramiche in Toscana [Florence, 1902], p. 368).

Copper and/or silver oxides were added to bisque-fired and glazed-fired earthenware vessels just before a third firing in a reducing atmosphere.

Alejandra Gutiérrez, Mediterranean Pottery in Wessex Households (13th to 17th Centuries), BAR British Series 306 (Oxford, Eng.: J. and E. Hedges, 2000), p. 185.

It had been recorded in 1585 that almost all of the residents of Muel were potters, and that the only “old Christians” were the priest, the notary, and the tavern keeper. Balbina Martínez Caviró, Cerámica Hispanomusulmana: Andalusí y Mudéjar (Madrid: El Viso, 1991), p. 236.

The NAA was conducted by Javier Garcia Iñañez and Robert J. Speakman; the unpublished results were conveyed to me in 2010.

Ibid. This vessel tested for Barcelona.

Douglas Killock et al., “Pottery as Plunder: A 17th-Century Maritime Site in Limehouse, London,” Post-Medieval Archaeology 39, no. 1 (2005): 1–91.

John G. Hurst, David S. Neal, and H.J.E. van Beuningen, Pottery Produced and Traded in North-West Europe, 1350–1650, Rotterdam Papers 6 (Rotterdam: Foundation “Dutch Domestic Utensils”: Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, 1986), p. 49. Fifty-seven sherds of Spanish lustreware, many of which relate to the same vessels, have been found in the Jamestown Rediscovery excavations.

Beverly Straube, “A faire Well of fresh water . . . ,” in William M. Kelso and Beverly A. Straube, Jamestown Rediscovery, 1994–2004 (Richmond, Va.: Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, 2004), p. 131.

Sean Kingsley, Ellen Gerth, and Michael Hughes, “Ceramics from the Tortugas Shipwreck: A Spanish-Operated Navio of the 1622 Tierra Firma Fleet,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2012), pp. 77–97; Sarah Newstead, “Merida No More: Portuguese Redware in Newfoundland,” master’s thesis, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 2008, pp. 84–85.

From visual inspection, the pitcher from James Fort with its distinctive vertical burnishing is considered to be from Aveiro. Kingsley, Gerth, and Hughes, “Ceramics from the Tortugas Shipwreck,” pp. 93–94.

Alejandra Gutiérrez, “Portuguese Coarsewares in Early Modern England: Reflections on an Exceptional Pottery Assemblage from Southampton,” Post-Medieval Archaeology 41, no. 1 (2007): 73.

Teresa Canepa, “The Portuguese, Spanish and Dutch Trade in Zhangzhou Porcelain (Part I),” Fujian Wenbo 72 (September 2010): 63.

Teresa Canepa, Zhangzhou Export Ceramics: The So-Called Swatow Wares (London: Jorge Welsh Books, 2006), pp. 31–32.

This information thanks to ceramics scholar Teresa Canepa and to Chinese archaeologist Li Jia’an; Jan-Erik Nilsson (http://gotheborg.com/glossary/jadehall.shtml).

Mike Hughes, “Scientific Study of the Glazes,” in Wally Davey and Helen Walker, eds., The Harlow Pottery Industries. Medieval Pottery Research Group Occasional Paper 3. ([London]: Medieval Pottery Research Group, 2009), pp. 161–163.

Wally Davey and Helen Walker, eds., The Harlow Pottery Industries, Medieval Pottery Research Group Occasional Paper 3 ([London]: Medieval Pottery Research Group, 2009), pp. 41–53; David Barker, “North Staffordshire Post-Medieval Ceramics: A Type Series; Part 2: Blackware,” Staffordshire Archaeological Studies, n.s. 3 (1986): 58.

Straube, “‘Captain John Smith’s Pots.’”

For a spoutless posset pot, see Aileen Dawson, English & Irish Delftware, 1570–1840 (London: British Museum Press, 2010), pp. 188–89.

Theodore Rabb, Enterprise and Empire: Merchant and Gentry Investment in the Expansion of England, 1575–1630 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1967), p. 103.

Phillip L. Barbour, ed., The Jamestown Voyages under the First Charter, 1606–1609: Documents Relating to the Foundation of Jamestown and the History of the Jamestown Colony . . . , 2 vols. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press for the Hakluyt Society, 1969), 1:212, 2:279; James A. Williamson, ed., The Observations of Sir Richard Hawkins [edited from the text of 1622] (London: Argonaut Press, 1933), p. 10.

Ivor Noël Hume and Audrey Noël Hume, The Archaeology of Martin’s Hundred (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology; Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2001), pp. 237–38; Richard Coleman-Smith and Terry Pearson, Excavations in the Donyatt Potteries (Chichester, Eng.: Phillimore, 1988), pp. 248–49.