Left: Jug, Robert and Thomas Swaine, Prescot, Merseyside (Lancashire), England, ca. 1825. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16 5/8". Mark: SWAINE. Center: Bottle, probably Frechen, Germany, ca. 1660–1680. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/2". Right: Flagon, probably Frechen, Germany, mid-eighteenth century. Salt‑glazed stoneware. H. 12 1/2". (Author’s collection; unless otherwise noted, all photos by Jason Dowdle.)

Jug, attributed to Peter Herrmann, Baltimore, Maryland, ca. 1870s–1880s. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9". Mark: SLADE.JONES.&.CO / DEALERS IN GENERAL / MERCHANDISE / HAMILTON. NC (Author’s collection.)

Jug, Salisbury, Rowan County, North Carolina, ca. 1755–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware with copper and manganese oxides. H. 10 1/2". (Author’s collection.) This jug fragment was found beneath a Salisbury building during its demolition. Similarly colored ware has been collected nearby.

Left: Standing-eagle bottle, attributed to Rudolph Christ, Salem, Forsyth County (Stokes County before 1849), North Carolina, ca. 1800–1821. Lead-glazed earthenware with copper oxide. H. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) Right: Turtle bottle, attributed to Rudolph Christ, Salem, Forsyth County, North Carolina, ca. 1800–1821. Lead-glazed earthenware with colored oxides. L. 8 1/2". (Author’s collection.)

Left: Standing flask, Alamance County, North Carolina (old St. Asaph’s District, Orange County), ca. 1770–1790. Lead-glazed earthenware with slip-trailed decoration. H. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) Right: Bottle, Alamance County, North Carolina, ca. 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware with slip-trailed decoration. H. 6". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Left: Jug, Jamestown, Guilford County, North Carolina, dated 1834. Salt‑glazed stoneware. H. 15 3/4". Marks: “10” and “1834”. (Courtesy, Richard and Carol Hay.) Right: Jug, Nathan B. Dicks, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1890. Lead-glazed earthenware.

H. 5 1/2". Mark (inscribed): N. B. DICKS new market n.c. Jan 12 1890 1 Pt. (Courtesy, Elizabeth Edmonds.)

Ten-gallon, two-handle jug, Daniel Seagle, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1840–1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16". Mark: D.S. 10 (From Nancy Sweezy and Mark Hewitt, The Potter’s Eye: Art and Tradition in North Carolina Pottery [Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006]. Used by permission of the publisher.)

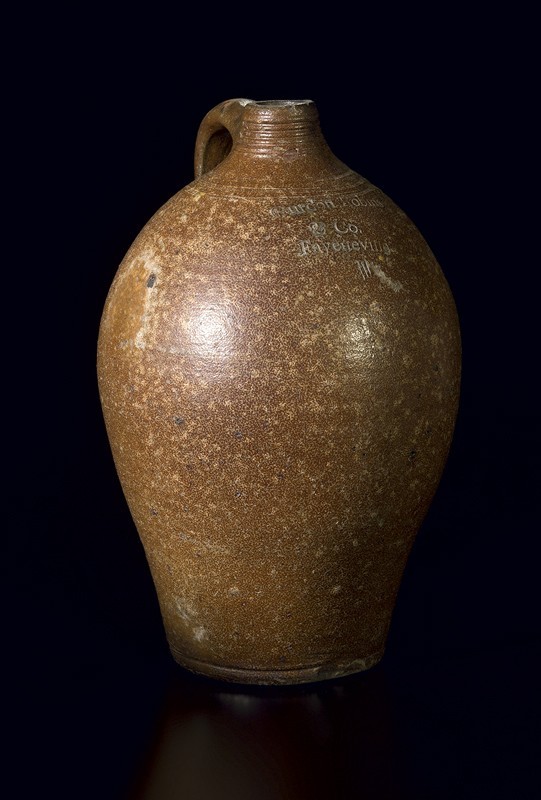

Three-gallon jug, attributed to Edward Webster, Fayetteville, North Carolina, ca. 1820–1823. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16 5/16". Mark: Gurdon Robins & Co. Fayetteville III (Courtesy, Quincy Scarborough.)

Four-gallon jug, attributed to Chester Webster, Randolph County, North Carolina, ca. 1840–1882. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 18". (Courtesy, Tommy and Ann Cranford.)

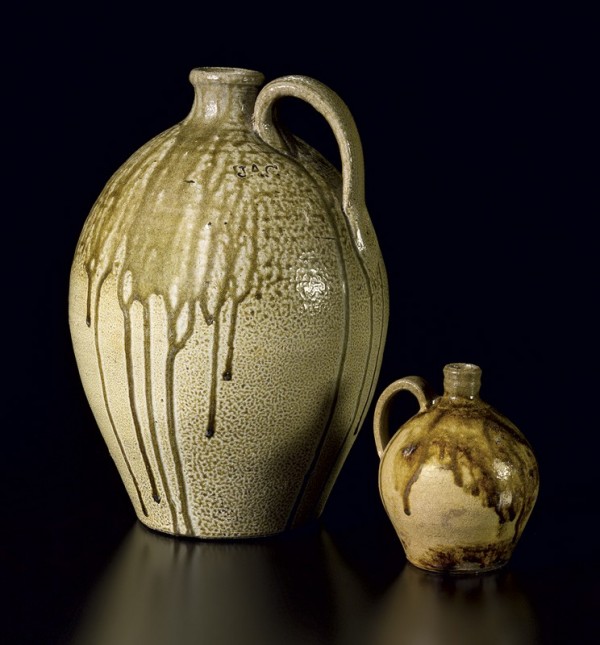

Left: Jug, John Anderson Craven, Randolph County, North Carolina, ca. 1850. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15". Mark: J.A.C. (Courtesy, David Ward.) Right: Jug, possibly Edward Stone, Buncombe County, North Carolina, ca. 1850–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 6 1/4". (Courtesy, Rodney H. Leftwich.) The glassy greenish-brown runs might be the result of applied slab glass. Most fly-ash runs are coincidental to a jug’s manufacture, yet they are so commonly found on North Carolina jugs that some effort may have been made to encourage them to satisfy customers’ preferences. The intentional addition of slab glass before firing was a simple way to add color and texture to a vessel’s surface.

Jug, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, ca. 1830–1860. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13". (Collection of Robert and Jimmie Hodgin; photo, Nancy Sweezy and Mark Hewitt, The Potter’s Eye: Art and Tradition in North Carolina Pottery [Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006]. Used by permission of the publisher.)

Jug, Nicholas Fox, Chatham County, North Carolina, ca. 1818–1858. Salt-glazed stoneware with incised circumferential bands. H. 19 1/2". Mark: N FOX [twice]. (Courtesy, North Carolina Pottery Center.) Highlighted by a distinctive salt-glaze “orange peel” surface and incidental kiln arch drips, this sturdy and handsome jug exemplifies the best of North Carolina’s eastern Piedmont stoneware production. Jugs made by Nicholas and his son Himer often bore an impressed Masonic “square and compass” symbol, suggesting that the potters were Freemasons.

Jug, William Nicholas Craven, Randolph County, North Carolina, ca. 1845–1857. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14 11/16". Marks, in cobalt blue (inscribed): S[t]ate / of nc / randolph / county; (stamped): W.N. CRAVEN (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Jug, David Hartzog, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1830–1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 12 7/8". Mark: DAVIDHARTZOGHISMAKE. [The 'S' is backwards.] (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

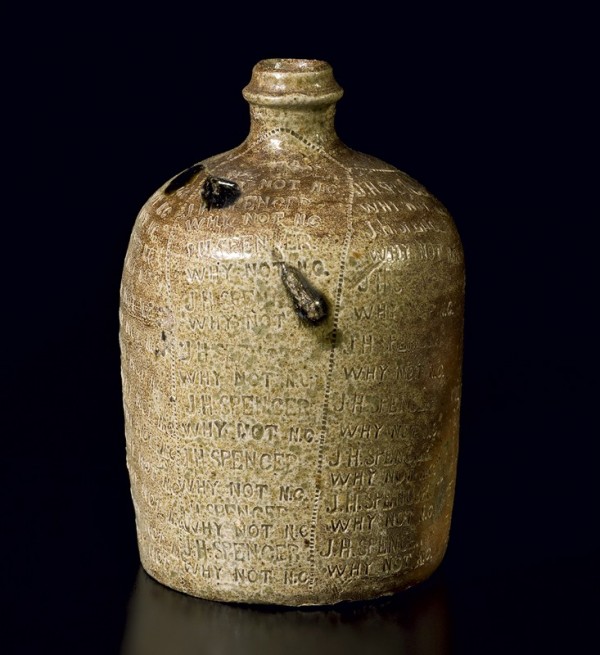

Bottle, Jordan Harris Spencer, Why Not, Randolph County, North Carolina, ca. 1868-1926. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8". Mark: J. H. SPENCER / WHY NOT N.C. [multiple times]. (Courtesy, Tommy and Ann Cranford.)

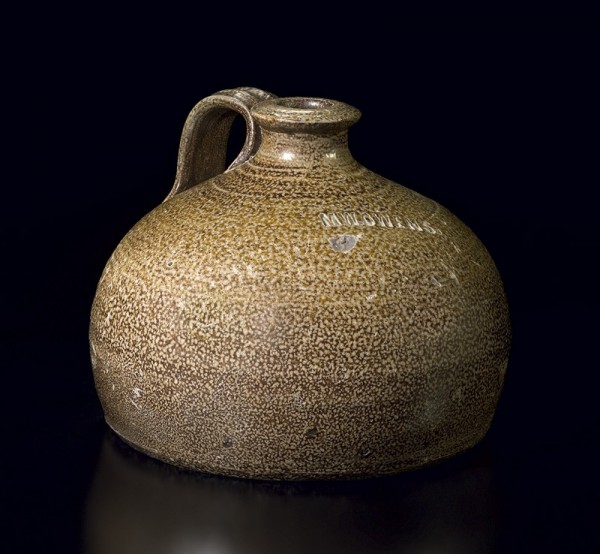

Buggy jug, Manley William Owen (or Owens), Randolph County, North Carolina, ca. 1880–1900. Salt‑glazed stoneware. H. 5 1/2". Mark: MW. OWENS. (Author’s collection.) As its name indicates, this modified tall jug was made short and wide, ensuring its stability when placed on the floorboards of a buggy or wagon.

Left: Rundlet, Nathaniel H. Dixon, Chatham County, North Carolina, ca. 1848–1863. Salt-glazed stoneware. L. 11". Mark: N. H. DIXON. (Courtesy, Steve Garner.) Right: Rundlet with bail handle, possibly Baxter Welch pottery shop, Harpers Crossroads area, Chatham County, North Carolina, mid-nineteenth century. High-fired earthenware. L. 7 1/2". (Author’s collection.) Rundlets were popularly used for transportation and storage of whiskey, beer, cider, and brandy. Some, like the smaller one seen on the right with a pouring spout protruding from its bung hole, could also be used for serving in a home or tavern.

Ring bottles. Left: Piedmont region, North Carolina, late eighteenth–mid-nineteenth century. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 9". (Author’s collection.) Right: William Henry Hancock, Moore County, North Carolina, ca. 1865–1900. Salt-glazed stoneware. D. 8". Mark: W. H. HANCOCK (Courtesy, North Carolina Pottery Center.) A footed ring-bottle form, allowing the jug or bottle to stand upright, is also known.

Jugs, James Otis Trull, Buncombe County, North Carolina, 1911–1912. Left: Single-chamber monkey jug, dated September 15, 1911. Albany slip–glazed stoneware. H. 9 3/4". Mark (inscribed): Sept 15 1911 Preasented by J O Trull (Courtesy, Rodney H. Leftwich.) Right: Long-necked jug, dated August 1912. Albany slip–glazed stoneware with fly-ash highlights. H. 7". Mark (inscribed): Made By J. O. Trull for C. B. Brock Candler R.F.D. August 1912 (Author’s collection.) No one knows with certainty how the term monkey jug came to be applied to a bulbous-bodied jug with a strap handle overhead and multiple openings. Similar jugs are common in Spain, Africa, and the Caribbean. Typically, one spout is for pouring and the other opening allows air to come in, improving the outflow of the jug’s contents.

Double-chambered monkey jugs, Vale, North Carolina. Left: attributed to William D. Bass, 1900–1935. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 9 1/2". (Courtesy, North Carolina Pottery Center.) Right: Harvey or Enoch Reinhardt, Reinhardt Bros. Pottery, ca. 1932–1936. Agateware (swirl) with clear glass glaze. H. 10 7/8". Mark: REINHARDT BROS. / VALE, N.C. (Author’s collection.) Like other, more whimsical jug shapes, there is no clear explanation for why some potters made double‑chambered monkey jugs.

Left: Saddle jug, Thomas Ritchie, Lincoln or Catawba County, North Carolina, ca. 1846–1900. Alkaline‑glazed stoneware. H. 7 1/2". Mark: TR 2 (Courtesy, Scott and Wendy Smith.) Right: Pinch bottle with cup/lid, Lincoln or Catawba County, North Carolina, late nineteenth–early twentieth century. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 6 3/4". (Author’s collection.)

Puzzle jug, Baxter Welch Pottery, Harpers Crossroads, Chatham County, North Carolina, ca. 1900. Salt‑glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Quincy Scarborough.) A purely whimsical form, this jug has a single spout but three miniature jugs masterfully mounted to its top. None of the small jugs opens into the larger host jug, which disqualifies it from being a true puzzle jug in the way of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century European examples. Nevertheless, someone three sheets to the wind might be amusingly befuddled when chasing a swig from this peculiar jug.

A typical moonshine still. (From Margaret W. Morley, The Carolina Mountains [1913]; photo, Courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina, N71.11.153.)

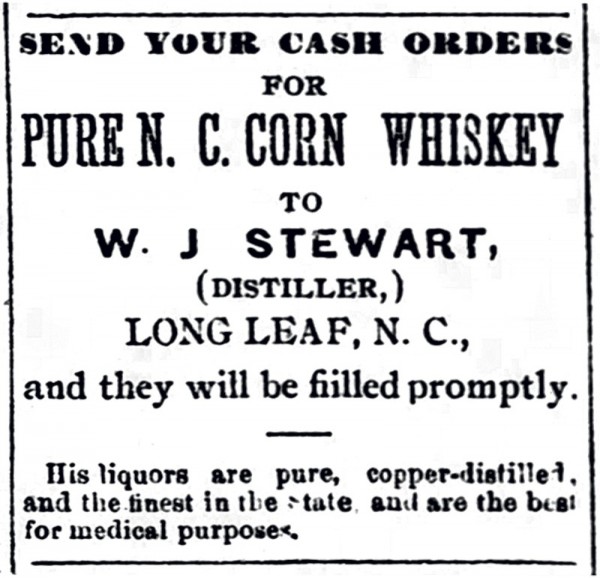

Advertisement for W. J. Stewart, potter and distiller, of Long Leaf, Moore County, North Carolina, who reportedly made whiskey on one side of his creek and jugs for it on the other side. (From The Carthage [N.C.] Blade, May 9, 1893.)

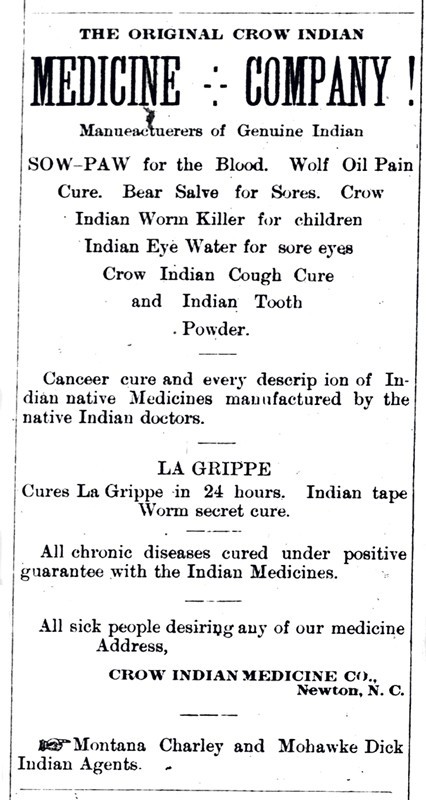

Advertisement for Crow Indian Medicine Co.’s Genuine Indian Sow Paw in Raleigh (N.C.) Signal, September 26, 1891.

Patent-medicine bottle, Lincoln or Catawba County, North Carolina, ca. 1892. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 6". Mark: GENUINE INDIAN / SOW PAW. (Courtesy, Scott and Wendy Smith.)

Jug, Luther Seth Ritchie, Catawba County, North Carolina, ca. 1895–1905. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/4". Mark: FROM J. C. SOMERS STATESVILLE, N.C. (Courtesy, L. A. and Suzan Rhyne.)

Stacker, or shoulder jugs. Left: ca. 1900. H. 11". Mark (incised): Lamort & Golay / Tryon N.C. (Courtesy, Scott and Wendy Smith). Center: C. C. Ballard, Wilkes County, North Carolina, ca. 1880. H. 8 1/4". (Author’s collection.) Right: ca. 1885–1900. H. 10 1/2". Mark (incised): Jay Bradley / Best Copper Distilled / Corn & Rye Whiskies / Jarretts / N.C. (Courtesy, Pem Woodlief.) Lamort and Golay were vintners and wine distributors in Tryon, Polk County, N.C. Jay Bradley operated a saloon in the state’s mountainous Nantahala Valley, at Jarretts, N.C., where he also produced corn and rye whiskey. The potter C. C. Ballard produced a hand-turned stacker jug festooned with a slab of glass melted over one side. In the early part of the twentieth century, Wilkes County, where the Ballard jug was made, was noted for its moonshining. The region’s fast-driving bootleggers triggered the creation of NASCAR racing.

“Swiglet” jugs, attributed to Auman Pottery, Seagrove, Randolph County, North Carolina, ca. 1928. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. of both 3 1/4". Marks (inscribed): Left, Al Smith; right, REGARDS TO O. J. COFFIN SHUCKS AND NUBBINS Z. H. RUSH (Author’s collection.)

Kennedy Pottery, North Wilkesboro, Wilkes County, North Carolina, ca. 1933. (Courtesy, Charles G. Zug III; photo, Ray A. Kennedy.) Claude L. Kennedy (left), Bulo Jackson Kennedy (center), and Converse Harwell mockingly pretend to pour their jug’s intended product into mugs of their own manufacture. For many years, the Kennedys, who employed a bevy of skilled potters, supplied jugs of many sizes to nearby moonshiners and government-licensed distillers.

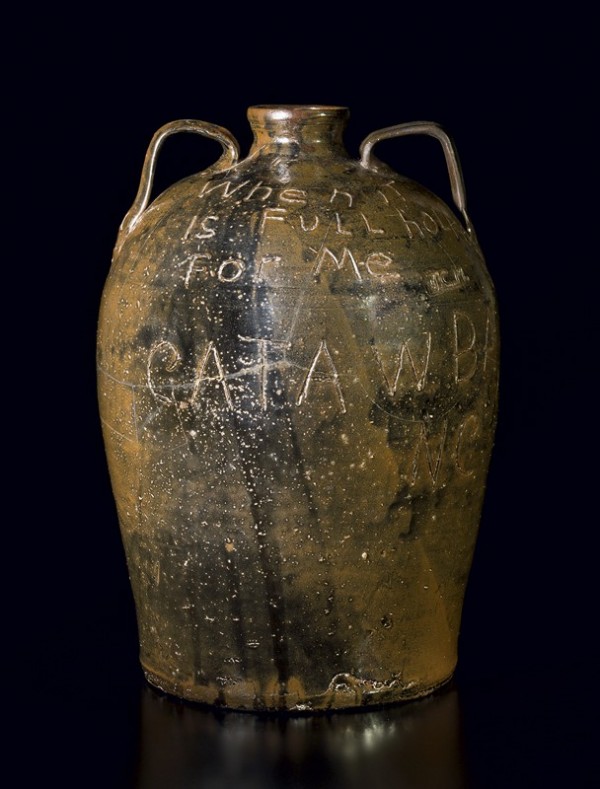

Five gallon, two-handle jug, T. Casey Meaders, Catawba, Catawba County, North Carolina, ca. 1922–1940. Albany slip glazed stoneware. H. 17 3/4". Marks (inscribed): When IT / IS FULL hollow [holler] / For Me / T.C.M. / CATAWBA / N.C.; on opposite side: Mr. Will Hedrick On The Road To Cat-fish. (Courtesy, L. A. and Suzan Rhyne.)

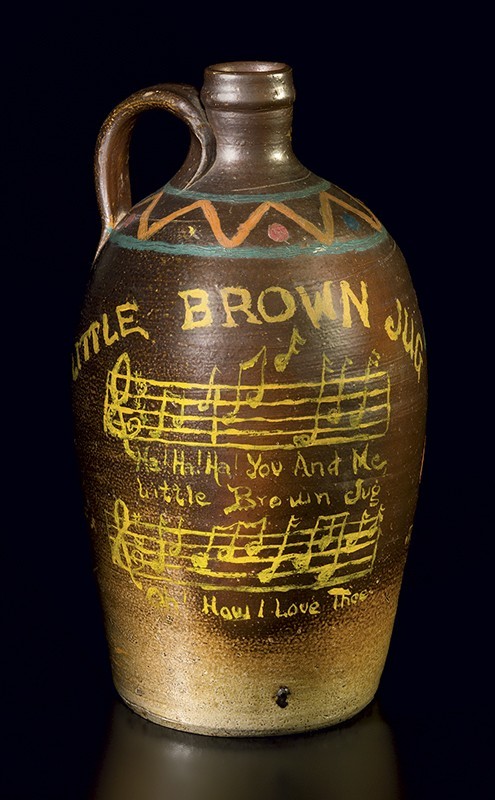

Jug, Jacob Dorris Craven, Randolph County, North Carolina, ca. 1860–1890. Albany slip-glazed stoneware. H. 12". Mark: J. D. CRAVEN (Author’s collection.) Decorated with painted-on chorus from the song “The Little Brown Jug,” words and music by Joseph Eastburn Winner, circa 1869. Originally written as a drinking song, “The Little Brown Jug” retained its popularity for many decades, including the years of Prohibition. In 1939 Big Band leader Glenn Miller recorded one of the best-known versions of it.

The history of jug making in North Carolina is inseparably tied to the manufacture, storage, transportation, and consumption of beverage alcohol. From the 1750s into the twentieth century, the state’s potters and distillers produced ample supplies of jugs and alcohol.

North Carolina’s first colonists quickly set up stills to manufacture alcoholic beverages, especially whiskey made from corn, rye, barley, or wheat. Poorly constructed and badly maintained roads—and, before the 1830s, the absence of railroads—made transporting farmers’ grain crops from one region to another a difficult and inefficient task. Distilled spirits made from these grains were much easier to transport, and the revenue gained from their sale contributed significantly to farmers’ incomes. Although distillers’ jobs were unencumbered by regulation, that was not true for long.

In 1791, following the Revolutionary War, the newly formed federal government levied a tax on whiskey. This first excise tax was championed by Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, who saw it as a way to retire the sizable war debt. Strong opposition to the tax, however, led to the Whiskey Rebellion. The tax was eventually repealed in 1803.

Whiskey was taxed once again after the Civil War, and legal distilleries were licensed and regulated by the U.S. Treasury Department, whose agents, known as “revenuers,” were responsible for collecting the tax. Yet for every tax-paying operation there were many more illegal stills run “in the pale moonlight” by so-called moonshiners.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the jug makers of North Carolina’s Piedmont (mid-state) and Mountain (western) regions were well positioned to supply containers for the storage and transportation of both legally and illicitly distilled spirits. In the early 1890s nearly twenty registered stills and an unknown number of unregulated ones were located in Randolph County alone. Reports of lawful and unlawful distilleries were similar across the state, county by county.

Instituted by law in the early years of the twentieth century, prohibition did little to reduce the production (or consumption) of distilled spirits in North Carolina. Wilkes County, in the foothills of the western Piedmont, gained the reputation as the state’s “moonshine capital.” The history of NASCAR stock-car racing is inextricably tied to stories of Wilkes County’s notorious “bootleggers,” whose fast cars transported loads of no-tax-paid whiskey over the area’s narrow, hilly, and curvy roads. And even though Wilkes County was known as the moonshine capital, many other counties rivaled its output of “white lightning.”

Whiskey was not the only alcoholic commodity produced by distillers. In the nineteenth century North Carolina was also the nation’s leading producer of wine. French vintners, among them Bordeaux’s A. J. Lemort, produced quality claret, sauternes, and sherry wines near Tryon, North Carolina.[1] Apple crops from western North Carolina and fruit crops from other regions were transformed into brandies.

Centuries before the first colonial settlers arrived in the sixteenth century, the area’s Native Americans made unglazed, low-fired pottery.[2] Later on, enslaved Africans, and perhaps some Native Americans as well, made colonoware.[3] The products of those potters certainly did not meet the first settlers’ requirements for leak-free, jug-like containers, however. That task fell to the area’s eighteenth-century colonial potters.

North Carolina’s colonization began along the Atlantic coast and spread westward as the area’s population increased. Jugs, like crocks, churns, and other vessels, were essential to the region’s residents for commercial and household use. To date, no example of locally made glazed earthenware or stoneware produced from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century in the coastal zone has been identified. However, extant jugs, primarily of English and German manufacture, have been found in association with old eastern estates and plantations and in excavated sites. Bellarmines and flagons, like the examples shown in figure 1, have been identified archaeologically in places such as Brunswick Town, on the Cape Fear River, which was laid out in 1725, and elsewhere along the coast.[4] Likely of German (Frechen) manufacture, vessels such as these were perhaps brought to the colony by British merchants. From 1725 to 1745 William Rogers, called the “Poor Potter” of Yorktown, Virginia, made at least four shipments of pottery to North Carolina ports in violation of British trade regulations.[5] Yorktown ware went to New England and West Indies ports, but the most popular destinations for it were Maryland and North Carolina.[6] Many “juggs” were delivered by ships landing near Brunswick Town and Wilmington in 1785.[7] In the early 1800s English brown salt-glazed stoneware bearing shop marks such as “SWAINE” (see fig. 1) and “YATES” was delivered to the state’s ports for purchase by coastal inhabitants. Plentiful examples of nineteenth-century stoneware originating in New York (e.g., Clarkson Crolius), Baltimore (e.g., Peter Herrmann), and other northern locales have been collected in the state’s eastern counties, suggesting that these potters were coastal suppliers. Herrmann went so far as to stamp-mark North Carolina–bound jugs, like the one shown in figure 2, with the names of merchants and the towns in which they were located.

North Carolina’s first known colonial potters established their shops in the 1750s in the Piedmont region’s rolling hills, far to the west of Coastal Plain settlements. Johannes Adam (John Adams) might have been the first, settling in Salisbury, Rowan County, in 1755. The jug remnant shown in figure 3 was recovered from under a Salisbury building during demolition and could be a Rowan County product. Later that same year, potter Gottfried Aust set up a pottery for the Moravian settlement at Bethabara. He subsequently established a second one at the new Moravian town called Salem nearby. His first kilnload of ware was produced in 1756. Aust, Rudolph Christ (who probably made the vessels shown in figure 4), and several other master potters served the Moravians and nearby residents for a century and a half.[8]

In old Orange County’s St. Asaph’s District (now southern Alamance County), Martin Loy established his own shop to supply the area’s growing population. He, or someone trained in his pottery, probably fashioned the flask and bottle shown in figure 5.[9]

Quaker potters probably came to the Guilford-Randolph county area in the mid-1700s. Family tradition has it that Peter Dicks (ca. 1720–1796) and Phillip Hoggatt (ca. 1687–1783) were potters. The region’s Quaker potters made vessels of many sorts, including jugs like the ones shown in figure 6. Among the first Quaker potters were William Dennis (1769–1847), Peter Dicks (1771–1843), Thomas Beard (1768–1820), and Mahlon Hoggatt (1772–1850).[10]

Some of the region’s potters made lead-glazed earthenware only; others made sturdy stoneware as well. In the eastern Piedmont, salt glaze was the preferred stoneware coating. In the Catawba Valley region to the west (primarily Catawba and Lincoln counties today), alkaline-glazed stoneware was produced. The stunning ten-gallon jug shown in figure 7, alkaline-glazed with applied glass runs, was made by the Catawba Valley’s premier nineteenth-century potter Daniel Seagle (ca. 1805–1867).[11]

A savvy Fayetteville (Cumberland County) merchant named Gurdon Robins, noting the need for locally produced stoneware, employed three potting brothers from Hartford, Connecticut—Chester, Edward, and Timothy Webster—to make stoneware for him. The Gurdon Robins & Company pottery began operation around 1820. Its workers created many kinds of vessels, such as the salt-glazed jug shown in figure 8, but the business closed after a few years. Edward Webster (1801–1884) continued his pottery making in Fayetteville until about 1838. Chester Webster (1799–1882) was drawn inland to Randolph County to work for the Craven family of potters, who had settled there as early as the 1760s. The magnificent jug illustrated in figure 9, bearing an incised drawing of a heron, was made by Chester Webster following his relocation from Fayetteville to near Coleridge, Randolph County. For many years the maker was known merely as the “bird and fish potter” after the many incised images found on his ware, but the discovery of a single example bearing the name c. webster helped to resolve the mystery of his identity.[12]

By the mid-nineteenth century, jug makers populated North Carolina’s Piedmont and Mountain regions. The salt-glazed jug shown in figure 10, its shoulder dripping with fly-ash runs, was made by Randolph County’s John Anderson Craven (1824–1859), one of the most skilled of his family’s numerous turners. The much smaller jug positioned beside it is from far-western Buncombe County, and may be the product of former South Carolina Edgefield District potter Edward Stone (b. ca. 1817), who had arrived in the state by 1844. Finished with alkaline glaze, its upper surface bears a molasses-like cap of drips and runs. This may have resulted from heavy fly-ash accumulation, but slab glass might have been laid over the jug’s top before firing to achieve the desired result. The frequent occurrence of fly-ash runs and applied glass decoration on North Carolina stoneware jugs suggests that the appearance was a feature preferred by some customers.

The eye-catching jug illustrated in figure 11 is attributed to Alamance County’s Solomon Loy (ca. 1805–ca. 1860), whose family may have made pottery in Berks County (Pennsylvania) and Virginia before coming to North Carolina in 1755. Jewel-like in appearance, a jug like this one with its fly-ash runs, glassy kiln arch drips, and underlying salt glaze would be one of its owner’s prized possessions, as well as a source of pride to the potter who made it.

Made just a few miles away from Solomon Loy’s kilns, the jug shown in figure 12 is twice marked N FOX for its maker, Nicholas Fox (1797–1858) of Chatham County. Fox’s father, Jacob, may have made pottery before him. Two of Nicholas’s sons, Himer (1826–1909) and Daniel (1845–1915), and three of his nephews turned ware. His sister, Elizabeth, married potter Anderson Craven (1801–1872). Known for their beautifully rounded bodies, pebbled salt-glaze surfaces, incised bands of lines, and stamped-in Masonic symbols, Fox jugs are among the state’s most striking examples.

William Nicholas Craven (1820–1903), son of Anderson and Elizabeth Fox Craven, made the fine jug illustrated in figure 13 before departing the state around 1857 for Missouri and Illinois, where he continued to turn ware. Though inconsequential to this particular jug’s functionality or durability, the addition of the cobalt-blue inscription of the location of its manufacture, as well as a bit of cobalt blue at the handle terminals and a drawn starburst on the side, suggest that it might have been custom-made for a friend, a nearby neighbor, or a county dignitary. No other example like it has been found.

Similarly, while the functional quality of David Hartzog’s (1808–1883) alkaline-glazed jug (fig. 14) is not increased by the addition of glass over its handle, iron slip over its side, and the band of stamped letters, the enterprising Catawba Valley potter, knowing that his neighbor and one of his nearest competitors was the superb master potter Daniel Seagle, may have made an extra effort to set his vessel apart from all others. The time required for the application of incised lines, the placement of glass on the jug’s handle and iron slip on its shoulder and side, and the letter-by-letter stamping of his name likely exceeded the time needed to turn and glaze the jug.

If his aim was to bring attention to his pottery skill, Jordan Harris Spencer (1847–1926) succeeded when he stamped the entire surface of a salt-glazed stoneware jug with his name and shop location (fig. 15). Why Not, an unincorporated community located near Seagrove, in Randolph County, was home to numerous nineteenth-century potters and today hosts many turners along what is called North Carolina’s “Pottery Highway.”

North Carolina potters offered a variety of specialized jug forms. Manley William Owen (or Owens) (1855–1910) created buggy jugs like the one shown in figure 16 by converting what otherwise would have been the upper portion of a much taller vessel into a short, squat one. With its low center of gravity, this form was less likely to tip over when placed on a wagon’s floorboards—and had the added benefit of keeping “wagoned” (i.e., illicit) liquor out of sight from the law.[13] His father, James J. Owen (1830–1905), was known for creating a form that he called a “Patent Jar,” which might have been used for fermentation.

Rundlets were made to store, transport, and pour beer, brandy, cider, and whiskey. The salt-glazed example with cobalt-blue bands illustrated in figure 17 was made by Nathaniel H. Dixon (1827–1863), who worked alongside his mentor, Nicholas Fox, before opening his own Chatham County shop. The other rundlet, a high-fired earthenware example with bail handle and pouring spout, was found in Chatham County near Harpers Crossroads, where Baxter Welch (1868–1947) employed some of the region’s most capable potters.

Ring jugs, like the ones shown in figure 18, represent the most enigmatic jug shape made by North Carolina’s potters. The form is not unique to the state, but the purpose of it is a mystery, even though examples were made throughout all of North Carolina’s pottery-making regions. Holding scarcely a pint of liquid, their practicality is questionable. They have been described as “harvest” or “mower’s” jugs, for taking a beverage to the fields or workplace. Some speculate that it’s merely a whimsical form, intended to showcase a potter’s prowess at the wheel. The notion has been raised that ring jugs had some symbolic meaning or a conjuring role, but such use remains in question.[14] Regardless of their intended purpose, the significant number of extant examples found within the state and dating to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries suggests that a considerable market existed for them.

In North Carolina’s mountains, potter James Otis Trull (1884–1958), among others, made a harvest-jug form called a “monkey jug,” which had a bulbous lower body and a pouring spout to aid in its use (fig. 19). With its topside handle, the monkey jug would have been easy to carry from a still to a tavern or home; the tall-necked jug shape seen in the example beside it might be unique to Trull. The examples illustrated in figure 19 were specifically made as presentation pieces and were signed by Trull.

Double-chambered monkey jugs, like the examples shown in figure 20, were most commonly created by the potters in the state’s Catawba Valley and mountains. The plain-colored alkaline-glazed example is attributed to the hand of William D. Bass (1874–1960), and the two-color agateware version is signed Reinhardt Bros. and was made in the 1930s at a Vale, North Carolina, shop run by brothers Harvey (1912–1960) and Enoch (1903–1978) Reinhardt. Double-chambered monkey jugs are made up of two stacked jugs, each one closed off from the other, allowing its owner to carry two different beverages at one time.

Called a “saddle jug” by some, the small flat-sided jug marked TR shown in figure 21 was made by Thomas Ritchie (1825–1909). Its name is derived from the belief that with its flattened sides it would fit neatly into a saddlebag. Since much larger versions of the form were made, the shape might have been preferred for tightly packing multiple jugs in wagon beds or crates. This small one could easily function as a flask. The unsigned pinch bottle, with its dual-purpose cup-lid, also shown in figure 21, accommodated tabletop serving and travel. Both examples are alkaline-glazed, as was customary for Catawba Valley stoneware.

Perhaps the most peculiar of all the shapes made in North Carolina is the “puzzle jug” (fig. 22). Unlike true puzzle jugs, this one made at Chatham County’s Baxter Welch pottery shop is a regular jug with a side-mounted spout but with the addition of three nicely turned small jugs (which do not have openings to the larger jug) applied to its top.

W. J. Stewart (1848–1932) was one of North Carolina’s most resourceful potters. Stewart made jugs on one side of his creek, and distilled whiskey on the other side (fig. 23). His government-regulated still and his pottery shop were located in Moore County’s Long Leaf community. In 1893 he advertised that he made “PURE N. C. CORN WHISKEY” and that “His liquors are pure, copper-distilled, and the finest in the state and are the best for medical purposes” (fig. 24).[15]

The claim that whiskey had medical purposes was hardly unique to Stewart. Old Christmas Whiskey, a brand manufactured near Warrenton, North Carolina, in the early 1870s for Christmas, Foote, and Co., was distilled by John J. Eades, a man said to be “the most celebrated Distiller in the State.” Recommended by its promoters to “all invalids . . . for its fine medicinal qualities,” this whiskey was declared to be the “best and purest Corn and Rye Whiskey ever offered for sale in North Carolina,” and was “guaranteed to be above proof, and twenty degrees stronger than Northern Whiskey.”[16] The brand had its detractors. A correspondent to the Biblical Recorder called Warren County’s “Christmas whiskey” the “bluest and meanest, and the most unfailing dead-shot ever invented,” advising its consumers “who are bent of self-destruction, to use some other poison so as not to die in fits of drunken madness.”[17]

Terms like moonshine, mountain dew, white lightning, popskull, and tanglefoot have been used to describe North Carolina whiskey. Another name for it, sow paw, may have been introduced to the area by Dr. Julian B. Ayer, alias Montana Charley, who touted his Genuine Indian Sow Paw “medicine . . . for the blood.” Ayer claimed that his medicines, including Wolf Oil (“instantly cures all pain”), and Worm Killer for Children (“the safest and best”) were prepared from original Indian formulas “free from poisons, perfectly safe to take and Swift to cure.”[18] In late August 1890 the name Sow Paw appears in an Anderson, South Carolina, newspaper. Montana Charley and his wild west show, complete with Indians, might have appeared in South Carolina before he set up his show in Catawba County, North Carolina, in 1890. By May 1891 the Crow Indian Medicine Company was manufacturing its medicine at Blackburn, the epicenter of Catawba County pottery-making (fig. 25).[19] The bottle shown in figure 26 likely was made by a Catawba or Lincoln County potter. It is coated with alkaline glaze and bears stamped lettering under the glaze: GENUINE INDIAN SOW PAW.[20]

Dr. Ayer called his concoction medicine, but soon the term sow paw was synonymous with whiskey. A Statesville observer noted in January 1892 that in his town “egg nog, punch, Tom and Jerry, &c, are becoming obsolete,” replaced by a “fashionable drink” called “Sow Paw,” “an acid enigma, portable in jugs and sold and drunk in back lots.”[21] In Catawba County, it was said that “Sow-paw has been flowing almost as freely as water.”[22] The term sow paw was used far and wide for “white corn licker,” as a Morganton (Burke County) writer explained it.[23] In Chatham County, a moonshiner known as the “Red Fox” was said to know “what time the moon is best for the Chatham sow-paw.”[24]

After the Civil War, jug makers could scarcely keep up with the demand for their products. As a Chatham County shop owner described, “two men are kept at work all the while and at certain seasons a dozen, and . . . there is a ready sale for the jugs.” His jugs sold at the grand price of ten cents per gallon.[25]

In 1884 nearly a dozen “jug factories,” as the pottery shops were sometimes called, were operating in the Catawba Valley. The Speagle and Johnson shop produced up to seven hundred gallons of jugs weekly. One Mooresville man purchased 1,500 gallons of jugs in a single order.[26] In 1890 William Weaver (1846–1925) made jugs in Brindletown, in Burke County, and brothers David (1866–1951) and George Donkel (1870–1956) left the Catawba Valley to set up a jug factory in mountainous Buncombe County.[27] Around 1892 M. J. Ritchie opened up the River Bend jug factory near Rozzelle’s Ferry in Gaston County.[28] Ritchie made weekly trips to Charlotte, selling as many as 250 jugs in a single visit.[29] During the Christmas season, wagonloads were delivered to Charlotte daily.[30] In Catawba County’s Blackburn community, Luther Seth Ritchie (1867–1940) erected a large pottery shop about 1894 that had as many as four “jug machines.”[31] Catawba County ware shops were said at the time to be “thicker than still-houses ever were in Wilkes [County].”[32]

By 1899 plans were made to add a telephone line between the Catawba Valley village of Blackburn and the town of Newton. “It will be a great advantage to these jug makers to telephone to their customers at Statesville,” claimed one reporter, “to those liquor dealers if they need anything in the shape of a jug.”[33] One who may have benefited most from the phone line was Luther “Uncle Seth” Ritchie. One of his customers was Statesville’s J. C. Somers & Co., a wholesale liquor house that distributed sweet and dry wines from the To-Kalon Vineyard in Napa County, California, as well as Somers’s own line of Iredell County whiskey. His whiskey brands included Catawba Chief Corn, Hunting Creek Rye, Poplar Log Corn, Red River Rye, and Somers Private Stock. The jug shown in figure 27 was made by Ritchie for J. C. Somers & Co.

North Carolina’s jug business boomed before Christmas each year to accommodate the transport and consumption of overflowing quantities of “Christmas whiskey.” In 1879 “revenuers,” aiming to destroy Enoch Callicott’s Montgomery County still, had found it “in full blast” just days before Christmas. Moonshiners George Luther and John Callicott escaped from the still, leaving the officers free to “cut down all the old stands, and cut the old still,” and to let loose the men’s horses. Luther and Callicott did not take kindly to the destruction of their still, and let the officers know it when they “fired on them from the bushes, at a distance of about one hundred yards, with squirrel rifles.” The still-raiding deputy estimated that the county was occupied by a desperado “gang” of blockaders, about twenty-five in number.[34]

A Wilmington reporter, speaking of Johnston County’s moonshine business in December 1890, noted, “The manufacture of ‘Christmas whiskey’ is very brisk and hence the revenue officials are specially active just now.”[35] “Revenue officers spoiled Christmas for some Gaston county people,” according to an 1898 report. “They raided in that county . . . and captured a moonshine plant three miles west of Dallas. Chris. Mauney was hard at work operating the plant when the Philistines swooped down upon it and captured him.” Over in the county’s Little Mountain section, revenuers raided another still, and “blasted the hopes and prospects of those who depended on sowpaw for a jolly Christmas.”[36]

Those who wanted their Christmas whiskey went to great lengths to get it, sometimes at significant personal cost. South Carolinian G. B. Kelly, from Darlington County, crossed over into Anson County, North Carolina, to acquire his supply of Christmas whiskey, in violation of South Carolina dispensary law. En route, his whiskey-laden buggy was halted by a posse of South Carolina lawmen armed with double-barrel shotguns. One of the men discharged his gun, sending a blast to the young man’s head. He died two days later.[37]

Dispensary-law violations and raids on stills notwithstanding, the Christmas whiskey business kept many jug makers busy. A 1904 newspaper account declared that, “The sow paw business is evidently looking for Christmas . . . the jug makers in Catawba county are so rushed with orders that they can hardly meet demands.”[38] But in the waning years of the nineteenth century and the early years of the twentieth, North Carolina’s jug trade suffered many challenges, including competition from out-of-state suppliers.

Georgian W. M. Fisk employed George Flesher to make jugs for him at a penny apiece, then retailed them in Charlotte in 1895 for six and seven cents each. Described as more ornamental than locally available jugs, “Fisk had no trouble in disposing of them.”[39] In 1906 one of the state’s merchants predicted the demise of jug-making in Union County. “Do you know,” he said, “that the making of jugs is going to soon be a lost industry in Union County? They will keep on making crocks and churns perhaps, but not jugs. Since the prohibition rules have become so strict and the people who are bound to have their liquor send off for it, there has become an overabundance of jugs. Liquor is shipped here in gallon jugs of a better grade than those made in the county, and this is making them cheap and plentiful.”[40] Some of the county’s jugmakers whose trade was at risk included Thomas (1837–1909) and Isaac Gay (1835–1904), William F. Outen (1860–1946), and James “Jug Jim” Broom[e] (1869–1957).

Near the beginning of the twentieth century, “manufactured” jugs increasingly found their way into North Carolina. Two examples, called “stacker” or “shoulder” jugs, are illustrated in figure 28, along with a handmade jug by Wilkes County’s C. C. Ballard (1860–1925) that mimics their shape. Combined with the increasing use of glass containers, the growing preference by distillers and buyers for these jugs made it difficult for old-school Carolina jugmakers to maintain their business.

Nothing had greater negative effect on North Carolina’s jug business than Prohibition’s “anti-jug” forces. Writing from the heart of the Catawba Valley’s jug-making region, a 1910 Hickory Democrat correspondent made clear his wish to see the jug trade diminish when he wrote: “Whether the liquor comes from a bar-room, a blind tiger, a drug store, a distillery the result is the same. The liquor coming in jugs has the same old effect. It won’t be long till we get national legislation to stop this jug trade. If we can drive out the bar room can’t we stop the jugs! If we can dam up a river can’t we dam up a branch?”[41]

Efforts to bring about such prohibitions began in North Carolina as early as 1852. In 1903 the Watts Act restricted the sale or manufacture of liquor to incorporated towns; two years later the Ward Law extended the restriction to towns that had fewer than one thousand residents.[42] Full statewide prohibition was enforced in January 1909, a full eleven years before implementation of the Eighteenth Amendment to the U. S. Constitution in January 1920.

As much support as Prohibition had among anti-alcohol forces, it was as often resisted or ignored altogether. The small jug shown on the left in figure 29, made at Randolph County’s Auman Pottery, bears the name of 1928 anti-Prohibition presidential candidate Al Smith. Enough examples like it exist to suggest that they were made to promote his candidacy. The Auman example seen to the right in figure 29 was presented to Smith’s contemporary, Oscar Jackson Coffin. Coffin, the University of North Carolina’s first School of Journalism dean, when asked about a post-Prohibition drink called “near-beer” said, “Whoever named it was a helluva judge of distance.” Coffin authored a column called “Shucks and Nubbins” for the Greensboro Daily News.

Wilkes County’s Kennedy Pottery supplied jugs to local moonshiners long after North Carolina’s prohibition laws were in place. In figure 30, a photograph taken several years after passage of the Eighteenth Amendment shows workers playfully demonstrating the usefulness of their ware for pouring and drinking.

Casey Meaders (1881–1945) moved away from his famous Georgia family of potters in about 1922 to work as a North Carolina journeyman before opening his own shop in Catawba County. He most likely made the drinking-themed five-gallon, two-handle jug illustrated in figure 31 for his neighbor William Hedrick (b. ca. 1871), whose name is inscribed on it.

The simple yet iconic Jacob Dorris Craven (1826–1895) jug shown in figure 32 might have been made in Randolph County to haul corn whiskey from a still to home, perhaps for someone’s stash of Christmas whiskey. Regardless of its first use, a past owner hinted at its purpose when the chorus of a well-known drinking song called “The Little Brown Jug” was painted onto it.

Prohibition did not end the consumption of alcohol in North Carolina, nor did it and other contrary forces end jug-making altogether. Yet, the heyday of jug-making for the alcohol trade was over by the 1920s, nearly two centuries after the first clay jug was turned on a North Carolina wheel.

Asheville (N.C.) Citizen Times, December 24, 1900, p. 7. Retired Union Army General Ulysses Doubleday brought A. J. Lamort of Bordeaux, France, and Lamort’s brother-in-law, a Mr. Golay of Switzerland, to Tryon, North Carolina, to grow grapes and make wine. Asheville (N.C.) Citizen Times, April 18, 1937, p. 2.

As early as 2500 B.C., Late Archaic–period Stallings series pottery was made in North Carolina. H. Trawick Ward and R. P. Stephen Davis Jr., Time before History: The Archaeology of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), p. 76.

Colonoware refers to low-fired, hand-built pottery found on colonial sites whose shapes sometimes mimic European forms.

Stanley South, Archaeology at Colonial Brunswick (Raleigh: Office of Archives and History, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 2010), p. 202.

Norman F. Barka, Edward Ayers, and Christine Sheridan, The “Poor Potter” of Yorktown: A Study of a Colonial Pottery Factory, Yorktown Research Series 5 (Denver, Colo.: Denver Service Center, United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, June 1984), vol. 1, p. 177.

Ibid., p. 174.

Charles G. Zug III, Turners and Burners: The Folk Potters of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), pp. 31–32.

For more about North Carolina’s Moravian potters, see Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter and Luke Beckerdite (Milwaukee, Wis.: Chipstone Foundation, 2009).

For more about North Carolina’s St. Asaph’s District potters, see Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter and Luke Beckerdite (Milwaukee, Wis.: Chipstone Foundation, 2010).

Hal Pugh and Eleanor Minnock-Pugh, “The Quaker Ceramic Tradition,” in ibid., pp. 68, 78, 85.

Seagle might have learned the trade from his father, Adam (ca. 1767–1834), while in Pennsylvania. Others who worked alongside him and excelled at pottery making were his son, James Franklin Seagle, his son-in-law John Goodman, Daniel Holly, and Isaac Lefevers.

The products Webster made in Randolph County differ somewhat from those made by him and his brothers in Fayetteville, perhaps due to his association with Craven family potters, who were established in the area as early as the 1760s.

Zug, Turners and Burners, p. 310.

The shape is reminiscent of the ouroboros, a circular symbol depicting a snake consuming its own tail; it is considered symbolic of infinity or wholeness. Examples of spouted ring vessels are known from the Mogollon culture (ca. 200–1450) of the American Southwest.

Carthage (N.C.) Blade, May 9, 1893, p. 3.

Tarborough (Tarboro, N.C.) Southerner, April 11, 1872, p. 1.

Biblical Recorder (Raleigh, N.C.), February 5, 1873, p. 2.

Newton (N.C.) Enterprise, May 1, 1891, p. 3.

Ibid.

Special thanks to Scott Smith, who identified Dr. J. B. Ayer (a.k.a. Montana Charley) as the purveyor of Genuine Indian Sow Paw.

Mecklenburg Times (Charlotte, N.C.), January 1, 1892, p. 2.

Ibid., January 29, 1892, p. 4.

Asheville (N.C.) Citizen-Times, July 10, 1900, p. 2.

News and Observer (Raleigh, N.C.), July 17, 1895, p. 8.

Newton (N.C.) Enterprise, September 28, 1900, p. 1.

Weekly State Chronicle (Raleigh, N.C), May 24, 1884, p. 1.

Hickory (N.C.) Press, January 30, 1890, p. 5.

Daily Journal (New Bern, N.C.), November 16, 1892, p. 1.

Mecklenburg Times (Charlotte, N.C.), February 8, 1894, p. 4.

Ibid., December 20, 1894, p. 4.

Hickory (N.C.) Press, February 22, 1894, p. 5.

Newton (N.C.) Enterprise, July 17, 1903, p. 3.

Times-Mercury (Hickory, N.C.), May 3, 1899, p. 2.

Observer (Raleigh, N.C.), December 23, 1879, p. 3.

Wilmington (N.C.) Messenger, December 20, 1890, p. 1.

Wilmington (N.C.) Morning Star, January 2, 1898, p. 2.

Messenger and Intelligencer (Wadesboro, N.C.), December 17, 1896, p. 3.

Oxford (N.C.) Public Ledger, December 22, 1904, p. 7.

Charlotte (N.C.) Observer, August 8, 1895, p. 4.

Monroe (N.C.) Journal, April 10, 1906, p. 1.

Hickory (N.C.) Democrat, May 12, 1910, p. 1.

K. Todd Johnson, “Prohibition,” Encyclopedia of North Carolina, edited by William S. Powell (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), p. 916.