Workspace of Stephen Earp, Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts, 2017. (Photo, Stephen Earp.)

Lidded jar, Stephen Earp, Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts, 2012. Earthenware. H. 12". (Photo, John Polak.) The early-nineteenth-century redware of Connecticut and Long Island has inspired much of my redware production.

Hervey Brooks kiln at Old Sturbridge Village, Sturbridge, Massachusetts. (Courtesy, Old Sturbridge Village.)

Joe Jostes demonstrating at the Colonial Market & Fair, George Washington’s Mt. Vernon, 2016. (Photo, Stephen Earp.)

A collection of ovoid black-glazed jugs, American, ca. 1820–1830. Earthenware. (Private collection; photo, Gridley + Graves Photographers.)

Dish, attributed to the Smith Pottery, Norwalk, Connecticut, ca. 1840. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 13". (Courtesy, Norwalk Historical Society).

Dish, workshop of the Albright/Loy pottery, Alamance County, North Carolina, ca. 1800. Slip-decorated earthenware. D. 15 1/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museum and Gardens.)

Plate, Stephen Earp, Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts, 2011. Sgraffitto-decorated earthenware. D. 11". (Photo, John Polak.)

Pitcher, Ken Henderson, Bangor, Maine, 2006. Earthenware. H. 7". (Author’s collection; photo Stephen Earp.)

Charger, Joe Jostes, Salesville, Arkansas, 2016. Earthenware with cabled slip design detail. D. 13". (Courtesy, S&J Pottery.)

“Water under the Bridge” vase, Ephraim Pottery, Lake Mills, Wisconsin, 2009. Earthenware. H. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Ephraim Pottery.) The formal naturalism and technical explorations of the Art Pottery movement continue to inspire potters today, as we see here.

Moravian-style slipware dishes, Tammy Zettlemoyer, Fort Frederick Eighteenth Century Market Fair, Fort Frederick State Park, Big Pool, Maryland, 2017. (Courtesy, Tammy Zettlemoyer.)

Ned Foltz with sculptural redware, Reinholds, Pennsylvania, 2016. (Courtesy, Sam Shoemaker.)

Face jug, Wesley Muckey, Mohnton, Pennsylvania, 2016. Earthenware. H. 14". (Courtesy, Nolde Forest Pottery.)

Lidded jar, Greg Shooner, Oregonia, Ohio, 2016. Earthenware. H. 14". (Courtesy, Shooner Redware.)

Mary Farrell demonstrates making an Alamance County, North Carolina, slipware bowl of the type illustrated in fig. 17.

Bowl, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790-1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 3". (Private collection.)

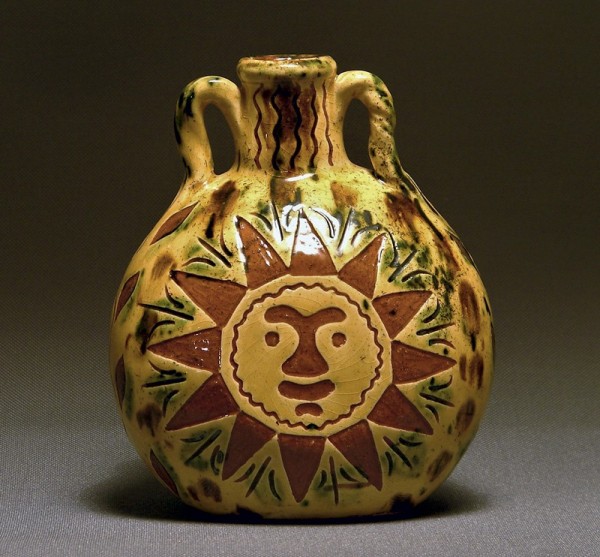

Costrel, Rick Hamelin and Garine Arakelian, Warren, Massachusetts, 2014. Earthenware. H. 6 3/4". (Courtesy, Rick Hamelin.)

English-style slipware charger, Ron Geering, Falmouth, Massachusetts, 2014. Earthenware. D. 13". (Courtesy, Ron Geering.)

Dish, Stephen Earp, Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts, 2016. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 13". (Photo, John Polak.) A similar pair of reclining deer on a plate in the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum of Colonial Williamsburg provided a prompt to explore compositions incorporating various animal and floral combinations.

Lidded mocha jar, Joe Jostes, Salesville, Arkansas, 2016. Earthenware. H. 10". (Courtesy, S&J Pottery.)

The Shooner wood-fired kiln in action. (Courtesy, Greg Shooner.)

Greg Shooner in his studio, 2017.

Dish, Stephen Earp, Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts, 2017. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 14". (Photo, John Polak.) In the delft style, the dish is inscribed “No handicraft can with our art compare, we make our pots of what we potters are.”

Plate, Don Carpentier, Eastfield Village, East Nassau, New York, 2010. Earthenware. D. 9". (Author’s collection, photo, John Pollak.) A circa 1760–style Staffordshire “tortoise-shell” pierced-and-glazed creamware plate.

Ceramic artist Eleanor Pugh demonstrating techniques of North Carolina slip decorating at Eastfield Village, East Nassau, New York, 2017. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Michelle Erickson demonstrating slip decorating of an early-eighteenth-century-style Staffordshire slipware cup. (Courtesy, Ceramics in America.)

America and Susquehannock, Michelle Erickson, Hampton, Virginia, 2017. Creamware. H. 29 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) Michelle Erickson was commissioned to design and create this pair of ceramic artworks. Based on eighteenth-century English cockle pots, these large-scale examples incorporate iconography inspired by a private collection of period prints, maps, and American furniture.

Lidded redware jar, Sue Skinner, Salesville, Arkansas, 2016. Earthenware. H. 9". (Courtesy, S&J Pottery.)

Tall sgraffito form, Ron Geering, Falmouth, Massachusetts, 2016. Earthenware. H. 17". (Coutesy, Ron Geering.)

Flower pots, Guy Wolff, Litchfield, Connecticut, 2018. Earthenware. (Photo, Visko Hatfield.)

The past isn’t dead. It isn’t even past. —William Faulkner

My initial education in ceramics was designed not only to ignore, but to actively shun early European and American traditions. And yet, today I work in several of them, such as redware and delftware (figs. 1, 2).

As a student in the 1980s, like many of my BFA classmates at the University of Iowa, I wanted to learn more about the rest of the world than the standard “time-line” view of history I was taught in high school. I enrolled in such courses as Sumptuary Arts of China and Japan, Art of Tribal Cultures, and Art of West Africa. In the pottery studio, the focus was on wood-firing, and on appreciating Chinese imperial porcelain and Japanese wood-fired stoneware, particularly through the writings of Bernard Leach, which we somehow blended with the Abstract Expressionism of Peter Voulkos.

The eclectic orientation of my classroom and studio experiences reflected a national trend in the 1980s toward a much-needed expansion of an earlier curricular focus on European and American leaders and thinkers to include other cultures and voices.[1] How this played out for us as ceramics students, unfortunately, was that nobody thought to examine the “unexotic” work of America’s colonial potters. We additionally disdained the potters of the Industrial Revolution, especially Josiah Wedgwood, whose name was seen as a byword for the impersonal, soul-crushing effects of the factory system.

A close reading of Leach, of course, reveals a more nuanced -appreciation of those historical ceramics, albeit with its share of glaring omissions (anything to do with America, for instance). As Mary Barringer, former editor of Studio Potter, relates, “Leach’s writings were spoon fed to students of the 1970s and early 1980s who had no serious understanding of the time periods in question.”[2] We lumped Euro-American ceramics into a vaguely defined “industrialization” category, and instead eagerly dived into Leach’s Sung dynasty and tea ceremony, along with the funky organic forms of Voulkos. Beyond that, with few exceptions, lay oblivion.

While the above description is a personal narrative, many potters of my generation can relate similar experiences. Andrea Gill of Alfred University’s Ceramic Program observes that American potters have for years preferred to draw fine-art inspiration from China and folk-art inspiration from Japan.[3] This attitude can still be seen today in Edmund De Waal’s 2015 porcelain travelogue The White Road. De Waal admits to a lack of interest in “the scholarship around small [European] kilns of the eighteenth century.”[4] He lambastes many European pottery forms (“a trembleuse, a chocolatier, a girandole”) as being frivolous and arcane, while reveling in the scholarship of Chinese kilns and, one could say, equally arcane Chinese forms (libation cups, monk’s-cap ewers, and kintua jars).[5]

I certainly had no problem with the perspectives described by Gill and De Waal when I graduated from the University of Iowa in 1986, nor in the following two years spent as an apprentice to Richard Bresnahan at St. John’s Pottery in Collegeville, Minnesota. I was attracted to St. John’s because of the in-depth exploration of the Japanese wood-fired tradition Bresnahan had experienced during his own apprenticeship to Nakazato Takashi, a Japanese National Living Treasure potter. Bresnahan indeed was (and is) well versed in this tradition. What he imparted to me, however, was the challenge to define my own role as an artisan in today’s society. To what end would I put my skills and abilities?

Looking to apply Bresnahan’s lessons, I traveled to Nicaragua as a ceramic technician for the craft assistance organization Potters for Peace. The focus on cultural preservation, so prevalent in Nicaragua at the time, motivated me upon my return home to make pots that had clear and direct connections to my physical, cultural, and historical surroundings. Ironically, after all my exploration of global ceramic traditions, so encouraged during my college years and afterward, I realized that I knew practically nothing about the ceramic history of my own backyard!

My introduction to this neglected heritage came in the form of Old Sturbridge Village (OSV) in Sturbridge, Massachusetts, where I worked as Master Potter from 1997 to 2003. OSV is one of the largest and oldest living- history museums in the United States. At OSV and similar institutions there existed, and still exists, a community of potters and other artisans dedicated to the preservation and advancement of traditional trades, techniques, and styles—what I refer to here as “traditional decorative arts” (fig. 3).[6]

The story of how this community came to be belongs to a chain of events that can be traced back to the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. There, the state of American crafts was judged against European achievements on display in those countries’ pavilions. The Philadelphia exhibit, and the ensuing American craft revival, were watershed moments for a previously languishing tradition of handmade pottery made and used in the U.S.[7] The writings of Barber, Watkins, Spargo, and others in the first decades of the twentieth century were also pivotal in preserving knowledge of, and interest in, earlier pottery efforts during this reevaluation of American ceramic achievement.

World War I had an equally momentous impact on handmade pottery in general and on traditional pottery-making specifically. Charles Zug’s exhaustive study Turners and Burners documents how that war’s shortages and rationing caused many traditional Southern stoneware potteries to close.[8] But the war also prevented American tourists from traveling to Europe.[9] A wave of nationalistic patriotism in reaction to the war coincided with the rise of the automobile to extend a predominantly upper-class tourist industry to include middle-class interests and the heritage of regional artistic activities within the U.S.[10]

Tourism had—and still has—a profound effect on pottery traditions of all types across the United States. As early as the 1880s, the Santa Fe Railroad’s Indian Department used Pueblo burnished and pit-fired pottery to promote the Southwest as “America’s Orient,”[11] leading to national awareness of and respect for the work of Pueblo potters. In 1921 Jacques Busbee founded Jugtown Pottery in Seagrove, North Carolina, in order to capitalize on a growing tourist interest in Southern stoneware.[12] In Massachusetts, the Peabody Historical Society hired John Donovan, an elderly potter who had worked for several regional redware shops, to make pots at the museum as “New England’s last redware potter.”[13] Redware potters of Pennsylvania also benefited from this shift to a tourist-oriented market. Folk-life shows such as the Colonial Market & Fair in George Washington’s Mount Vernon (Virginia) and the Kutztown (Pennsylvania) Folk Festival, featuring work made in traditional styles, appeared from the 1920s onward (fig. 4).[14] Later open-air museums, historical reenactments, and Rendezvous encampments of the living-history movement found fertile ground in this environment.[15]

As I progressed at OSV, I absorbed the imperative of stylistic accuracy, typified by the preservation-oriented orthodoxy common among living-history museum staff. I also began to appreciate aspects of traditional Euro-American pottery styles that I hadn’t considered before. Redware, the most popular and widely practiced of these styles in the U.S. today, seemed to tap into a universal level of craft expression, including clear parallels with rural Nicaraguan and Japanese “folk” pottery. Each of these traditions was shaped and influenced by the limits of its immediate environment, and to a large degree each was made for and by agrarian communities (i.e., farmer-potters), mainly utilizing whatever local materials were at hand as their kilns and forms developed to meet the needs of local economies. Now, each caters to a more urbane audience. I have often wondered what the great sixteenth-century Japanese tea-master Sen no Riky¯u might have thought of American redware if he had lived in the late eighteenth century, as he mined rural Japanese pottery villages for his tea equipage.

OSV also led me to appreciate various types of redware on a more formal level (figs. 5-7). Plain brownware, the most ubiquitous type of historical redware, conveyed a quiet self-assurance that is pure elegance in its expression of form and volume. Slipwares, particularly from Norwalk, Connecticut, offered quirky, often enigmatic (to my modern eye) adages fluidly sprawled in Spencerian script across plates and chargers, resulting in a unique home-grown calligraphic style. The Moravian and Quaker potting communities of North Carolina created an unparalleled body of exuberant floral slipware.

Northern Palatinate German immigrants brought their own distinct sgraffito approach, called “tulipware” by Barber, to local pottery making in southeastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey.[16] Several years after becoming involved in this work, I learned an interesting aside about the tenacity of the original German immigrant tulipware potters. During the first several decades after they established communities here, these Germans were reviled as ignorant and wholly alien foreigners by previously established populations.[17] Yet the tulipware potters persisted. After declaring for the patriot cause during the Revolutionary War, they proudly displayed their heritage through their pottery and other decorative arts. Tulipware flourished after the war. This style has now become the most popular type of redware produced in the U.S. today (fig. 8).

Looking further, what I once dismissed as “factory work” now appeared as a vast range of fascinating ceramic expression. The proto-industrial output of blue-and-white delftware offered complex cultural and artistic feedback loops spanning continents and centuries. The nineteenth-century transformation of English Rockingham into its American incarnation resulted in a polychrome wonder that at times seemed to me like an “American T’ang” glazing style (fig. 9). Techniques and styles blossomed at a rapid-fire rate between the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, from early English slipware, agateware, scratch-blue stoneware, and creamware to transfer-print and flow-blue ironstone. And then, of course, there was mocha, or “dipped ware, with its explosion of color and design.[18] British ceramics decorated in the mocha tradition incorporated the boldest and most daring application of slips I had ever seen (fig. 10).

All these developments occurred during a period of unmatched, freewheeling exploration in ceramics in the United States and Europe. These often unrecognized or underappreciated traditions have profoundly impacted the essential fabric of today’s ceramic arts world, from the development of our materials supply system, to wheel and kiln designs, production techniques such as slip casting and ceramic decals, glaze chemistry, and more. The range and depth of this new (to me) field of activity was astonishing. How could we, as students back in the 1980s, have missed this story?

Too many of my generation’s teachers, informed and inspired by a selective reading of Leach and of history in general, soured our interest in these Euro-American traditions. Too many within my generation who now teach in ceramic fine-arts programs have, in turn, neglected to expose the next generation of ceramic artists to any broad historical ceramic appreciation at all. Instead, according to Andrea Gill, “the time-line approach is overshadowed by teachers going deep into one subject, then teaching that to beginning students.”[19] I believe many of today’s potters are not so antagonistic to those earlier Euro-American styles as much as they are ignorant about them (fig. 11).

But, times are changing. For inspiration potters can now access nearly all of the world’s cultural heritage at the tap of a screen. The growing allure of traditional pottery today seems most clearly expressed by interest in the wood- and salt-fired stoneware of North Carolina.[20] Southern stoneware, along with the earthenware traditions of southwestern Pueblo cultures, are the most widely recognized traditional American ceramic styles, and a number of publications, exhibits, conferences, and even entire museums are dedicated to their preservation and advancement. They certainly belong in the greater narrative of ceramics made and used in the United States, both historically and today.

I wish to highlight another group of ceramic artists working in many of the other Euro-American styles mentioned previously. These artists occupy a complicated position in today’s ceramic scene. Some contemporary ceramic art colleagues consider them to be (with notable exceptions) anachronisms who make only “reproductions,” and offer nothing new, unique, or original. Ceramic arts programs rarely encourage the study of these artists or the styles in which they work. And, if one were not born and raised in a community or culture that originated these styles, nor learned them directly from a “tradition bearer,” one is considered an interloper by some of the public and private arts agencies that support traditional crafts.

Yet this loosely defined group represents a substantial portion of traditionally oriented potters in the U.S. today (fig. 12). Patrons of museum gift shops, Americana galleries, and living-history and traditional decorative arts events—the lifeblood of many of these artists—appreciate the clear historical reference points in the potters’ work.[21] And practitioners of those styles offer unique and valuable insights into the study of past ceramic achievements. In the words of redware potter Sue Skinner of Salesville, Arkansas, “We do a lot of explaining.”[22]

Many potters working in historical styles today profess to be self-taught, although this term mainly refers to how they learned this specific type of work rather than how they learned pottery making in general. A few, like Pennsylvania’s Wesley Muckey of Mohnton and Sam Shoemaker of Reinholds, belie the notion that redware died out from the industrialization of the nineteenth century. These two learned from potters with direct connections to nineteenth-century tulipware: Shoemaker is the nephew of Ned Foltz (who is still active), and Muckey began making redware when he was sixteen years old, working for Lester Brenninger (who passed away in 2011) (figs. 13, 14). Foltz and Brenninger, two legendary pioneers of contemporary redware, studied at Stahl’s Pottery in Powder Valley, Pennsylvania, in the 1950s. Stahl’s opened its doors in 1840, and, as a beneficiary of the early-twentieth-century tourism boom, lasted until the 1970s.

Certain regions, particularly southeastern Pennsylvania, provide potters with a compelling context for making work reflective of distinct local historical styles. Wesley Muckey, for example, reports little need to travel much beyond local festivals. Customers looking for his unique interpretations of Pennsylvania tulipware generally come to his Nolde Forest Pottery or find him on the internet.[23]

But anything can spark the flame. The Mercer Museum’s Folk Fest in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, inspired redware potter Denise Wilz of Macungie, Pennsylvania. “It used to be a really hot show, one of the best,” Wilz says. “You could see all these people making this work and demonstrating their techniques. It was stunning.”[24] Redware potter Greg Shooner of Oregonia, Ohio, relates how his first encounter with the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s tulipware collection inspired him to dedicate his career to that authentic look, rather than the more kitschy reflections of redware prevalent in the late 1970s and early 1980s (fig. 15).[25] Another redware and colonoware potter, Tammy Zettlemoyer of Hamburg, Pennsylvania, first planned on attending the Alafia River Rendezvous in Homeland, Florida, for two weeks and ended up staying seven. “This was the beginning of my life in the national [living-history] circuit.”[26]

Interest in and revivals of past ceramic achievements have been witnessed throughout history. Ancient Romans and Chinese reveled in re-creating earlier work. The nineteenth-century workshops of Deruta, Italy, elaborated and expanded earlier Spanish and Italian lusterware traditions.[27] Some of the late-nineteenth-century German Gothic Revival potters utilized original sixteenth-century Siegburg molds in their work.[28]

Many of today’s traditional decorative-arts potters continue to recognize value in the “reproduction” approach, which offers an inviting and affordable option for anyone interested in owning examples of these styles. Since 1977, Mary Farrell of Westmoore Pottery in North Carolina has provided invaluable contributions to the educational mission of museums and historic sites across the country with her reproduction redware and stoneware (figs. 16, 17). Mary was presented with a Barringer Award for Excellence by the North Carolina Society of Historians in 2010.[29] Furthermore, according to redware potter Rick Hamelin of Warren, Massachusetts, customers generally appreciate not just the items they purchase, but the stories behind those items (fig. 18). These stories, written in ceramics, touch upon many of our nation’s greatest successes and its most challenging chapters: from tulipware and the immigrant experience, to delftware and international trade, face jugs and slavery, colonoware and the Native American colonial-era experience, or transfer print and the effects of industrialization, to name a few.

According to Lori Bolduc, an Italian maiolica-inspired potter of Snohomish, Washington, “this technique [i.e., reproduction] is absolutely required to learn a particular style. It puts me in the mind of the original makers—breaking down the process into its elements. Once one knows the rules of the style, it is easy to take it where you want to go as a modern artist. And that is the fun part.”[30]

Furthermore, most of today’s historically oriented potters have at least occasionally accepted reproduction commissions as a supplement to their regular production. Besides, what potter has not, at some point, pondered the challenge of trying their hand at such efforts—if only as an exercise in how close their own skills might come to that mark? Ron Geering of Woods Hole, Massachusetts, describes his early efforts at making replicas as “mainly to satisfy myself that I could do it,” before developing his own approach to English slipware and sgraffito (fig. 19).[31] But as Rick Hamelin warns, “a danger with doing reproduction work is that the client might or might not agree to the exactness of the finished product.”[32]

Regardless of these considerations, some observers still consider this work, as a whole, to be merely “copying what someone else has already done.” As Mary Barringer suggests, this situation can at least partly be due to the general tendency of Euro-American traditional potters to “over-emphasize their sources of inspiration.” Barringer continues, “nobody doing wood-fired tea wares today [for example] will say they are making Japanese knock-offs. It’s all about them as makers in their own right.”[33]

In contrast, most, if not all, traditional decorative-arts potters have no difficulty emphasizing their sources of inspiration, whether or not they consider their own work to be reproductions (fig. 20). Sue Skinner maintains that “we are honest,” pointing out that no work, traditional or contemporary, exists within or comes from a vacuum (fig. 21).[34] A major aspect of working in any style is the acceptance of definitions and boundaries as road maps for further exploration. As such, many of the potters mentioned here focus, as Greg Shooner and Mary Spellmire-Shooner explain, on “accuracy in style, rather than dimension” in their work. The Shooners in particular have created a body of work, including lead glazes and stressed surfaces, that is breathtakingly authentic in its own right and in its reflection of historical redware (figs. 22, 23).

When I mention to other potters that I make redware, I occasionally hear the reply “so you make reproductions, then?” It is almost as if we are speaking past each other using different languages. I suspect this confusion could be clarified from a deeper study of the traditional decorative arts, beginning within the fine-arts curriculum. The fine-arts perspective values first and foremost the uniqueness of individual vision, with all efforts evaluated primarily according to that criteria. The traditional decorative arts perspective equally appreciates fidelity of style, and how the individual vision addresses the collective tradition (fig. 24). As mocha practitioner Joe Jostes, husband of Sue Skinner and co-owner of S&J Pottery in Salesville, Arkansas, succinctly puts it, “It’s like the blues. You do your riff, I do mine, but it’s all the blues.”[35]

Education plays an important role in many potters’ decision to become involved in this work, for both personal and professional reasons. Ken Henderson, an Old Sturbridge Village alumnus, echoes a common experience of those potters who began making this work via the living-history movement: “OSV instilled in me the importance of personal research. I knew that I could and should learn more.”[36]

Don Carpentier, another legendary figure in the field of traditional ceramic activity, created his own living-history “Eastfield Village” in East Nassau, New York, in order to preserve and promote early trades, particularly his meticulously produced mocha, machine-lathed, shell-edge, and tortoiseshell-glazed pottery (fig. 25). Carpentier passed away in 2014, but Eastfield Village continues to be an important laboratory for “experimental archaeology,” the study of historical techniques designed to increase knowledge of, and generate new ideas about, past material-culture developments (fig. 26).

Another prominent figure in experimental ceramic archaeology is Michelle Erickson of Hampton, Virginia. Her important contributions to this field have been featured in many venues, including several past issues of Ceramics in America.[37] Erickson’s experimental archaeology work, like Carpentier’s regular production, is remarkably exacting in its adherence to historical antecedents. Erickson also stands out as perhaps the most nationally, and internationally, recognized ceramic artist to successfully combine a long study and technical mastery of traditional forms and styles with contemporary commentary (figs. 27, 28).

Tensions between originality and historical authenticity have also, unfortunately, affected relationships among some advocates for traditional decorative arts, dating as far back as 1976. Then, Ivor Noël Hume criticized “the burgeoning manufacture of reproductions, fakes, and unabashedly modern and totally worthless objects designed specifically for the ‘collector market.’”[38] Spikes of interest in this work following national anniversaries came in for particular scorn from Hume, “[f]or at such times anything remotely relevant becomes available in replica.”[39]

Much has changed since the 1970s when, as Joe Jostes recounts, “everyone was just feeling their way forward.”[40] More important, folklorist Lynn Martin Graton recounts that today fewer and fewer people are born into commonly recognized traditional circumstances. Not only have markets dramatically altered over the years, but “certain outsiders make many personal sacrifices to preserve [and] master the technical demands of those traditions, and express them with artistic depth and with cultural sensitivity.”[41] Graton suggests that original guidelines pertaining to traditional work are now perhaps both too rigid and too vague in deciding “who’s in and who’s out” as arts agencies and others consider how such “traditional” work is defined.

Furthermore, not all arts organizations share these stricter guidelines. Early American Life’s National Directory of Traditional Craft focuses exclusively on the quality and scholarship of the work rather than personal biography. The directory provides a wonderful starting point for anyone interested in learning “who’s who” in this traditional decorative-arts sphere. Most of the artists mentioned in this article (full disclosure, myself included) have at some point been listed in the directory, and for the most part the ceramic artists mentioned in this article feel an irresistible kinship with historical Euro-American styles. “The intimate narrative of daily life displayed on much early American redware fits my sense of whimsy,” adds Sue Skinner. Such figurative representations offer a perfect prism through which Skinner presents her own fanciful combinations of characters acting out life’s comedy and drama (fig. 29).

The potters featured here, and many of their colleagues working in traditional decorative-arts styles, have assumed a degree of responsibility to the heritage represented by these styles in order to avoid the glib “sampling” or blatant appropriation that too easily can define approaches to the historical record. Their work offers valuable lessons to students of historical pottery by respectfully addressing preservation and evolution—in other words, originality and historical authenticity—often in the same piece. According to Ron Geering, “I have always felt strongly that traditional craftspeople should intimately know the work of their predecessors but must use this knowledge to make work that represents their own personal abilities, world view, attitude, and the social situation they find themselves in.” The main thing, according to Geering, is that “you need to make a contribution” (fig. 30).[42]

I believe that, taken on its own merits, contemporary work that reflects, interprets, and promotes traditional Euro-American pottery styles is being produced at its highest level ever, with the best of its practitioners propelling these traditions forward in ways that celebrate past achievements while adapting to modern circumstances.

In her 2015 book Big Magic Elizabeth Gilbert addresses the tricky path these potters often navigate between preservation and innovation:

So what if we repeat the same themes? So what if we circle around the same ideas, again and again, generation after generation? So what if every new generation feels the same urges and asks the same questions that humans have been feeling and asking for years? We’re all related, after all, so there’s going to be some repetition of creative instinct. Everything reminds us of something. But once you put your own expression and passion behind an idea, that idea becomes yours. Anyhow, the older I get, the less impressed I become with originality. These days, I’m far more moved by authenticity. Attempts at originality can often feel forced and precious, but authenticity has quiet resonance that never fails to stir me. Just say what you want to say, then, and say it with all your heart. . . . If it’s authentic enough, believe me it will feel original.[43]

Guy Wolff of Litchfield, Connecticut, explains his motivation for working in these historical styles in a manner that eloquently invites other potters to further exploration: “When you see a historic pot, your breath stops. Why does it have so much vigor and honesty? You can’t replicate that, but you can spend a lifetime trying to figure it out” (fig. 31).[44]

I can’t speak for, or even know, the full range of potters working in historical Euro-American styles today. But what we do as makers of these works has the potential to influence others’ interest in and opinions about the historical record. It is important for us to continually ask what we want to impart. What are we leaving out? Even more important, to what end is this work being done? Let the conversation continue.

History on Trial, ed. Gary B. Nash, Charlotte Crabtree, and Ross E. Dunn (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1997), p. 79.

Personal communication with Mary Barringer, September 2, 2016.

Personal communication with Andrea Gill, August 20, 2016.

Edmund de Waal, The White Road: A Pilgrimage of Sorts (London: Random House, 2015), p. 18.

Ibid., pp. 17, 72, 80, 97.

When asked in an interview about the distinction made between “art” and “decorative arts,” Michelle Erickson stated, “For me it doesn’t really make any sense. Largely art is not useful—it’s decorative. And for some reason, ‘decorative arts’ includes a lot of utilitarian objects.” Lauren Oyler, “Feminist Ceramicist Michelle Erickson Makes Pottery Political,” Broadly (August 14, 2015), https://broadly.vice.com/en_us/article/qkg9jp/feminist-ceramicist-

michelle-erickson-makes-pottery-political (accessed January 24, 2019).

Edwin Atlee Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1909), p. 294.

Charles Zug, Turners and Burners: The Folk Potters of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: -University of North Carolina Press, 1986), p. 389.

Marguerite S. Shaffer, See America First: Tourism and National Identity, 1880–1940 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Press, 2001), p. 100.

Ibid., pp. 33, 132.

Ibid., p. 59.

Zug, Turners and Burners, p. 393. Note also Busbee’s decision to focus “on the wares of the Han, Tang, and Sung Dynasties, which are best noted for their powerful forms, monochromatic glazes, and lack of elaborate surface decoration” in order to better appeal to a modern tourist market.

Thanks to Rick Hamelin for this information. Watkins discussed John Donovan several times in her book Early New England Potters and Their Wares (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1950), pp. 64, 65, 71, 93, 112, 113, but failed to note that he first worked at the Lamson Dodge pottery in New Hampshire. From there he traveled to East Brookfield, Keene, and Peabody.

Shaffer, See America First, p. 288. Shaffer notes how the Arts and Crafts movement “emerged in the early decades of the twentieth century as an ambiguous antimodernist response to the increasing fragmentation and rationalization of modern urban-industrial living.” Middle-class Americans increasingly sought “authentic” experience,” “real” life, and self-fulfillment through craftsmanship, romantic nature, and more “primitive” ethnic others. These forays into an idealized pre-modern past served as a palliative for the ills of urban-industrial society.

Thanks to Joe Jostes and Tammy Zettlemoyer for their descriptions of Rendezvous encampments. The Rendezvous circuit includes participants in period costumes re-creating aspects of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, particularly the fur trade. Some Rendezvous encampments last as long as two weeks, and are occasionally “closed camps”—i.e., open to the public for only a few hours on certain days.

Edwin Atlee Barber, Tulip Ware of the Pennsylvania-German Potters (New York: Dover Publications, 1926), p. 87. Barber draws the name from the original German “Tulpenware.”

Liam Riordan, Many Identities, One Nation; The Revolution and Its Legacy in the Mid-Atlantic (Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press, 2007), p. 31.

Jonathan Rickard, Mocha, and Related Dipped Wares, 1770–1939 (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2006), p. 50.

Personal communication with Andrea Gill, August 20, 2016.

“Tales of a Red Clay Rambler,” episode 50, interview with Matt Jones, podcast audio, January 29, 2014, http://carterpottery.blogspot.com/2014/01/matt-jones-on-tales-of-red-clay-rambler.html.

According to Historic Deerfield gift-shop manager Tina Harding, the unrelated business income tax (UBIT) regulates the items nonprofits can make for resale that can be purchased without paying sales tax. For an item to qualify for the UBIT exemption, it must reasonably relate to the mission of the institution. Personal communication with Tina Harding, August 30, 2016.

Personal communication with Sue Skinner, July 27, 2016.

Personal communication with Wesley Muckey, October 18, 2016.

Personal communication with Denise Wilz, September 3, 2016.

Personal communication with Greg Shooner, September 5, 2016.

Personal communication with Tammy Zettlemoyer, January 25, 2017.

Alan Caiger-Smith, Luster Pottery (New York: New Amsterdam Books, 1985), p. 129.

Ivor Noël Hume, If These Pots Could Talk (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2001), p. 109.

www.westmoorepottery.com/pages/About-Us.html (accessed February 12, 2019).

Personal communication with Lori Bolduc, July 13, 2016.

Personal communication with Ron Geering, July 20, 2016.

Personal communication with Rick Hamelin, August 22, 2016.

Personal communication with Mary Barringer, September 2, 2016.

Personal communication with Sue Skinner, July 27, 2016.

Personal communication with Joe Jostes, August 17, 2016.

Personal communication with Ken Henderson, August 22, 2016.

Michelle Erickson and Robert Hunter, “Dots, Dashes, and Squiggles: Early English Slipware Technology,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 94–114; Michelle Ericson and Robert Hunter, “Swirls and Whirls: English Agateware Technology,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2003), pp. 87–110; Michelle Erickson and Robert Hunter, “Making a Bonnin and Morris Pickle Stand,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Easthampton, Mass.: Antique Collectors’ Club for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), pp. 141–64; Michelle Erickson and Robert Hunter, “Making a Moravian Squirrel Bottle,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter and Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2010), pp. 200–216; Robert Hunter and Michelle Erickson, “Making a Moravian Faience Ring Bottle,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter and Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2010), pp. 190–99.

Ivor Noël Hume, All the Best Rubbish (New York: Harper & Row, 1974), p. 52.

Ibid., p. 147.

Personal communication with Joe Jostes, August 17, 2016.

Lynn Martin Graton, “The Evolving Focus of Public Sector Support for Folk & Traditional Arts,” presented to the New Hampshire State Council on the Arts, May 11, 2006.

Personal communication with Ron Geering, July 20, 2016.

Thanks to Eric Smith for sharing this quote. Elizabeth Gilbert, Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear (New York: Penguin Random House, 2015).

Personal communication with Guy Wolff, September 6, 2016