Sideboard table with carving attributed to Martin Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Mahogany with white oak; marble. H. 32 1/2", W. 62 3/4", D. 31 5/8". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) All dimensions were taken from the frame. The pieces of figured marble veneer forming the top are bonded to a gray stone core with a roughly worked rear edge. The solid molded edges are attached to the core in a manner similar to cross-banded moldings on wooden tops. The top has a complex history of breakage and repair. Most of the veneer pieces at the ends and all of the side moldings have been replaced; iron and steel splints have been added to the undersurface; and losses on the top have been filled.

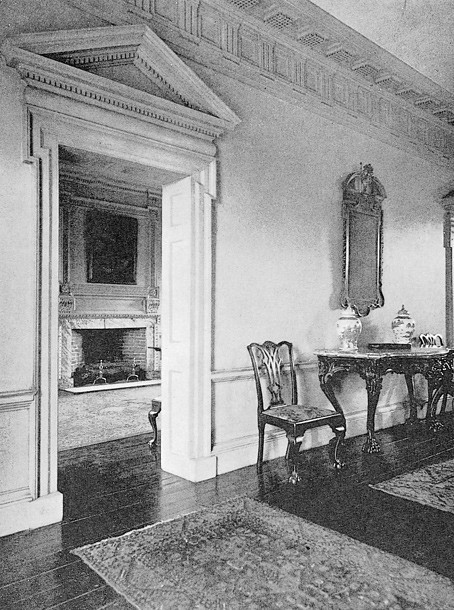

View of the hall in Mount Pleasant showing the sideboard table illustrated in fig. 1. (Philip B. Wallace, Colonial Houses: Philadelphia, Pre-Revolutionary Period [New York: Architectural Book Publishing Co., 1931], p. 157.)

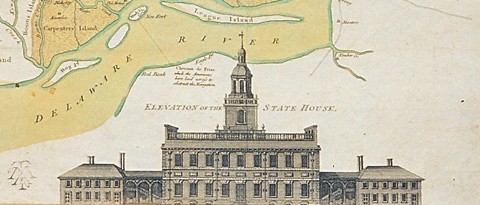

Elevation of the north façade of the Pennsylvania State House shown on Matther A. Lotter, A PLAN of the City and Environs of PHILADELPHIA, Pennsylvania, 1777. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

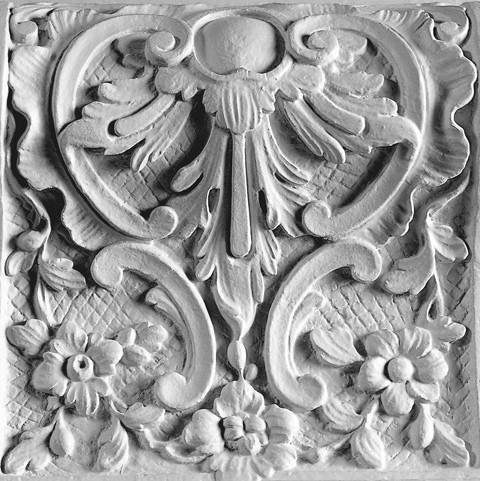

Frieze appliqué in the stair tower of the Pennsylvania State House. (Courtesy, Independence Hall National Historic Site; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the appliqué on the frieze of the tabernacle frame in the Assembly Room of the Pennsylvania State House. (Courtesy, Independence Hall National Historic Site.)

Detail of the appliqué on the frieze of the tabernacle frame in the Assembly Room of the Pennsylvania State House. (Courtesy, Independence Hall National Historic Site.)

Desk-and-bookcase with carving attributed to the shop of Samuel Harding, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1740–1755. Walnut with tulip poplar, yellow pine, and white cedar. H. 112", W. 40 3/4", D. 23 3/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the tympanum appliqué on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 7. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The appliqués on either side of the bookcase shell are so undercut that they make little contact with the tympanum and appear to float over it.

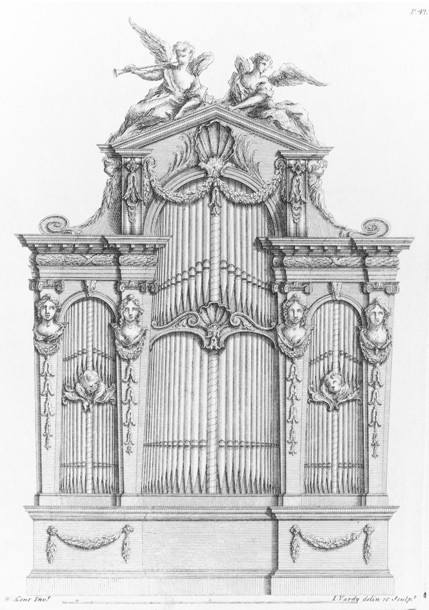

Design for an organ case illustrated on pl. 47 in John Vardy’s Some Designs of Mr. Inigo Jones and Mr. William Kent (1744). The engravings in this book depict Kent’s designs from the early 1730s.

Detail of a tympanum appliqué attributed to Nicholas Bernard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, probably late 1740s. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The appliqué is on the upper section of a high chest or chest-on-chest attributed to the shop of Philadelphia cabinetmakers Henry Cliffton and Thomas Carteret. The lower section is missing.

Franklin stove, attributed to Warwick or Mount Pleasant Furnace, Chester or Berks County, Pennsylvania, ca. 1745. Cast iron. H. 31 1/2", W. 27 1/2", D. 35 3/4". (Courtesy, Mercer Museum of the Doylestown Historical Society; photo, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

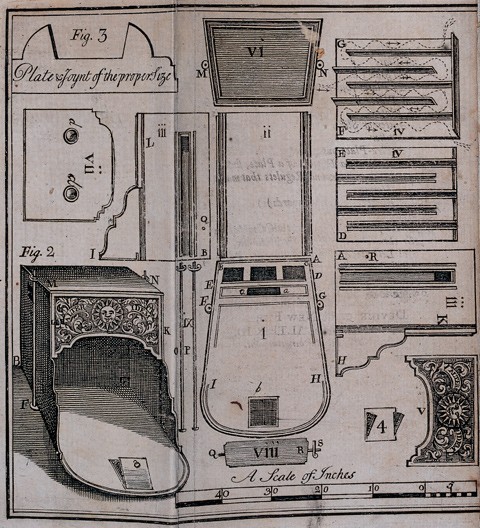

James Turner (act. 1744–1759) after Lewis Evans, design for Franklin’s Stove, illustrated in An Account of the New Invented Pennsylvanian Fire-places. (Courtesy, Library Company of Philadelphia; photo, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

High chest with carving attributed to Nicholas Bernard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, probably late 1740s. Walnut with tulip poplar, yellow pine, and white cedar. H. 91 1/2", W. 42 1/2", D. 24 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Philip Bradley Antiques.) The construction, knee carving, and underscale claw-and-ball feet on this piece have parallels in other Philadelphia case pieces from the mid- to late 1740s.

Detail of the right front foot of the high chest illustrated in fig. 13. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet of this chest are similar to those on the side chair illustrated in fig. 16.

Detail of the intaglio carving in the upper chamfer returns of the high chest illustrated in fig. 13. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This is the earliest intaglio carving associated with Nicholas Bernard. No other pieces with incising in this context are known.

Side chair with carving attributed to Nicholas Bernard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1750. Mahogany with white cedar. H. 41 1/2", W. 22 3/8, D. 17 1/2". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet of this chair are related to those on the earliest case furniture attributed to Bernard (see figs. 13, 14). They do not occupy the full thickness of the stock and have an extra joint in the rear talon.

Detail of the back of the side chair illustrated in fig. 16. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the front rail and knees of the side chair illustrated in fig. 16. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair with carving attributed to Nicholas Bernard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1755. Mahogany with white cedar. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The feet of this chair are larger than those on the Lambert chairs (see fig. 16) and are more typical of Philadelphia work from the 1750s. They occupy the full thickness of the stock, are more in scale with the leg, and do not have the extra rear knuckle. The carving on the back and knees activates the form, whereas the ornament on the Lambert chairs is simply visual static. Three of Bernard’s competitors carved chairs of this same basic design.

Sideboard table with carving attributed to Nicholas Bernard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1750–1755. Mahogany with yellow pine and tulip poplar. H. 29 1/4", W. 49 1/2", D. 20 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, gift of Claneil Foundation in memory of Lois McNeil.) This sideboard table is one of three related examples. For the rails of these tables, Bernard used complex background designs with foreground elements intended to dominate the flow of line.

Detail of the carving on the rail of the sideboard table illustrated in fig. 20.

Detail of the knee carving on the sideboard table illustrated in fig. 20.

Card table with carving attributed to Nicholas Bernard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1750–1755. H. 28 1/2", W. 36", D. 17" (closed). (Private collection; photo, Christie’s.)

Card table with carving attributed to the “Garvan high chest carver,” Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, probably late 1750s. H. 29", W. 36", D. 16 3/4" (closed). (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Sideboard table with carving attributed to Nicholas Bernard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1755. Mahogany with unidentified secondary woods; clouded limestone. H. 29 1/2", W. 49 7/8", D. 22 1/2". (Courtesy, Pendleton House Collection, Rhode Island School of Design.)

Detail of the knee carving on the sideboard table illustrated in fig. 25. (Photo, Luke Beckerdite.)

Chest-on-chest with carving attributed to Nicholas Bernard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1755–1760. Mahogany with tulip poplar, yellow pine, and white cedar. H. 97", W. 42 1/4", D. 24". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Dauphin County, Harrisburg, Pa.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the pediment of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 27. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Bernard used a pattern to lay out his cartouche ornaments. Occasionally he flipped the pattern to make the ornament face in the opposite direction.

Sideboard table with carving attributed to Nicholas Bernard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1755–1760. Mahogany. H. 30 3/4", W. 36", D. 19 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, gift of Henry Francis du Pont.)

High chest of drawers with carving attributed to Nicholas Bernard and Martin Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1760. Mahogany with tulip poplar, yellow pine, and white cedar. H. 94", W. 44", D. 23". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dressing table with carving attributed to Nicholas Bernard, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1760. Mahogany with tulip poplar, yellow pine, and white cedar. H. 32", W. 36", D. 21". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) All of the carving on the dressing table is attributed to Nicholas Bernard.

Detail of the relief-carved shell and flanking appliqués on the lower center drawer of the high chest illustrated in fig. 30.

Detail of the pediment of the high chest illustrated in fig. 30. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The double C-scroll ornament diVers significantly from the asymmetrical ones attributed to Bernard and their more elegant counterparts produced by the “Garvan high chest carver.”

Side chair with carving attributed to Nicholas Bernard, 1755–1760. Mahogany with tulip poplar and white cedar. H. 40 1/2", W. 21 1/4", D. 16 3/4". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This side chair and the example illustrated in fig. 36 share several construction features. The spaces created by their overlapping shoes are filled with thin glue blocks. These blocks also serve as the foundation for the larger quarter-round blocks glued inside the rear corners of the seat frame. The asymmetrical carving on the crest rail of this chair is virtually identical to that on several other chairs attributed to Bernard, and the shell on the front seat rail is similar to that in the center of the front rail of the card table illustrated in fig. 23.

Detail of the knee carving on the side chair illustrated in fig. 34. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair with carving attributed to Martin Jugiez, 1760–1765. Mahogany with yellow pine and white cedar. H. 40", W. 21 7/8", D. 16 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Although the carving on the crest rail and front seat rail is exceptional, the knee acanthus is relatively coarse. In general, eighteenth-century carvers expended more effort on ornament that was closer to the eye.

Detail of the cartouche on the crest rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 36. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

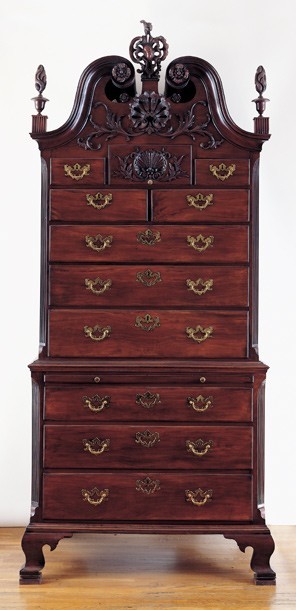

Chest-on-chest with carving attributed to Martin Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1760–1765. Mahogany with tulip poplar, yellow pine, and white cedar. H. 95 3/8, W. 39 1/2", D. 24". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the pediment of the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 38. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

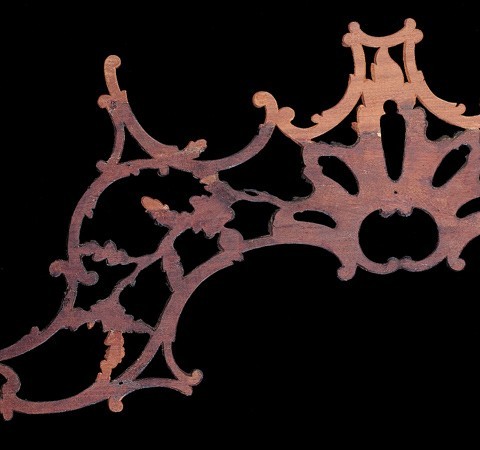

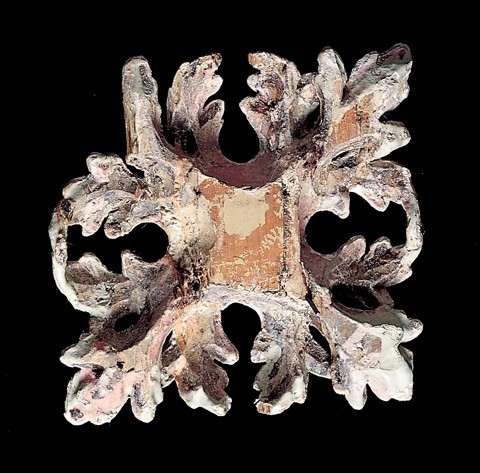

Detail showing the back of the tympanum appliqué on the chest-on-chest illustrated in fig. 38. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Tall clock case with carving attributed to Martin Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, c. 1770. Mahogany with white cedar. H. 97 1/2", W. 21 3/4", D. 12 5/8". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The movement is from the shop of London clockmaker William Addis, and the dial arch is inscribed “THE PHILADELPHIA PACKETT.”

Detail of the hood of the tall clock case illustrated in fig. 41. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair with carving attributed to Martin Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Mahogany. H. 39 1/2", W. 25 1/2", D. 23 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

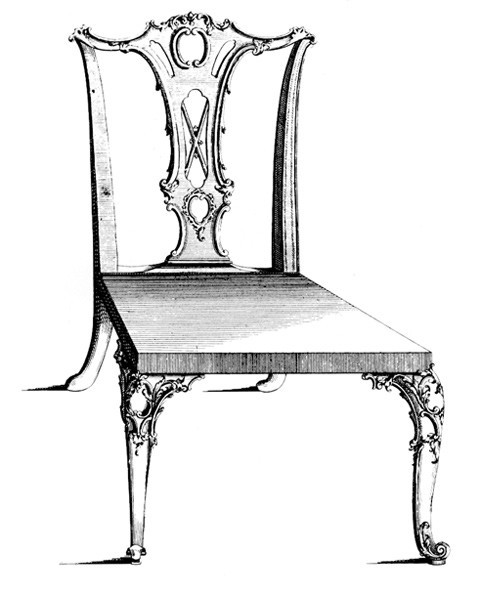

Design for a side chair shown on pl. 12 of the first and second editions of Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754, 1755). (Courtesy, Winterthur Library.) This design appeared on pl. 14 in the third edition (1764).

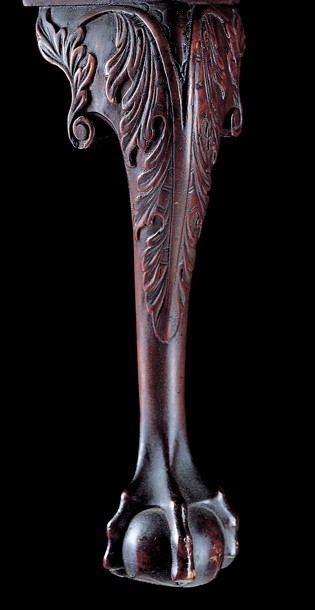

Detail of the carving on the leg and foot of the side chair illustrated in fig. 43. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left ear on the crest rail of the side chair illustrated in fig. 43. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the splat of the side chair illustrated in fig. 43. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair with carving attributed to Martin Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Mahogany with yellow pine and white cedar. H. 40 3/8, W. 22 7/8", D. 17 3/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

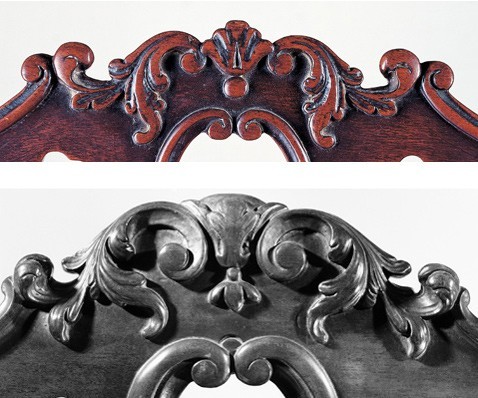

Detail showing the carving on the claw-and-ball-foot side chair (above) and scroll-foot side chair (below) attributed to Jugiez (figs. 43, 48). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Side chair with carving attributed to Martin Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1775. Mahogany with white cedar. H. 41 1/2", W. 21 7/16", D. 16 3/8. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the knee carving on the side chair illustrated in fig. 50. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Interior of St. Peter’s Church, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1763, with organ and case installed ca. 1764. (Courtesy, St. Peter’s Church; photo, Luke Beckerdite.)

Detail of the carving around the pipes of the organ case illustrated in fig. 52. (Photo, Luke Beckerdite.)

Detail of the carving on the lower section of the organ case illustrated in fig. 52. (Photo, Luke Beckerdite.)

View of the second-floor parlor in Mount Pleasant, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1764. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The large appliqué between the trusses on the chimneypiece is missing, but clear witness marks survive.

Detail of the large tympanum appliqué on the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 55. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The small flower at the top of the appliqué came from the side of a truss and is incorrect for the design.

Detail of the upper left flower at the top of the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 55. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the back of the flower illustrated in fig. 57. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

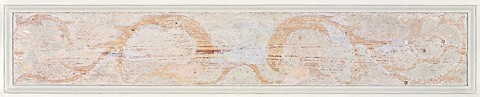

Detail of the witness marks for the appliqué originally installed on the frieze of the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 55. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing a chimneypiece from Whitby Hall. (Courtesy, Detroit Institute of Arts; City of Detroit Purchase, photograph © 1986.) This appliqué is attributed to the “Garvan high chest carver.” The small flowers in the lower crossetts were copied from examples illustrated on pl. 4 in Abraham Swan’s British Architect (1745).

Fireback, Marlboro Furnace, Frederick County, Virginia, ca. 1770. Cast iron. 34 1/2" x 31". (Courtesy, United States Army Engineer Museum, Fort Belvoir, Virginia; photo, Robert Hinds.)

Finial bust of John Locke attributed to Martin Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Mahogany. H. 10 1/2". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Bernard and S. Dean Levy, Inc. in honor of Bernard Levy, 1992.)

Finial bust of John Locke attributed to Martin Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Mahogany. H. 10 1/2". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Bernard and S. Dean Levy, Inc. in honor of Bernard Levy, 1992.)

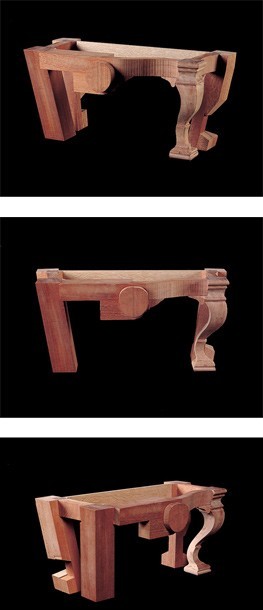

Side and frontal views of a model showing the relative stock dimensions and laminate scheme of the sideboard table illustrated in figs. 1, 63. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The surfaces of the front rail behind the laminates were planed.

Detail of the hewing marks on the top of the front rail of the sideboard table illustrated in figs. 1, 63. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the inner rails of the sideboard table illustrated in figs. 1, 63. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carving on the knee of the right front leg of the sideboard table illustrated in figs. 1, 63. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Jugiez carved right over the ends of the pins securing the mortise-and-tenon joints.

Detail of the right truss of the chimneypiece in the second-floor parlor of Mount Pleasant. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The truss and other carved components are yellow pine.

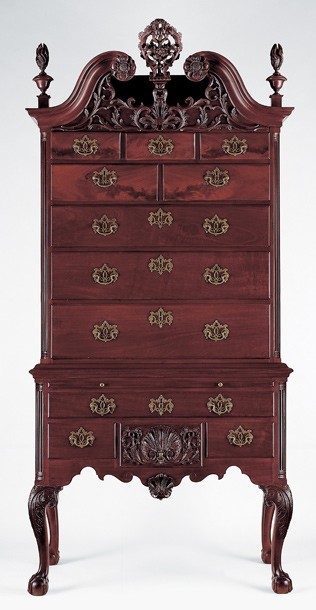

High chest with carving attributed to Martin Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770–1775. Mahogany with yellow pine, tulip poplar, and white cedar. H. 96 3/4", W. 45 1/2", D. 24 1/2". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

Detail of the carving on the lower right quarter-column of the high chest illustrated in fig. 69.

Detail of the carving on the drawer and skirt of the high chest illustrated in fig. 69.

Detail of the lion’s head on the sideboard table illustrated in figs. 1, 63. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the right side of the sideboard table illustrated in figs. 1, 63. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Design for a sideboard table attributed to Matthias Lock, England, ca. 1745. Pencil on paper. 8 3/4" x 6 7/8". (© V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London, www.vam.ac.uk.)

Design for a sideboard table attributed to William or John Linnell, England, 1750–1760. Ink and watercolor on paper. 2 1/4" x 4 1/2". (© V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London, www.vam.ac.uk.) Linnell’s drawing depicts a table in the Palladian style and makes no reference to the prevailing rococo. In the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries British architects, designers, and their patrons frequently visited Italy on the grand tour. They found inspiration for architecture and case furniture in Roman buildings and works by such later architects as Andrea Palladio but saw no classical tables or seating furniture to emulate. By default, they adopted aspects of contemporary northern Italian furniture design. Linnell’s drawing reflects this stylistic migration, which Jugiez completed when he crossed the Atlantic.

Sideboard table, Italy, 1740–1760. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Giuseppe Morazzoni, Il Mobile Veneziano [Milan: Görlich, 1958], pl. 155.)

Art historians and decorative arts scholars tend to consider sculpture and carving as mutually exclusive categories. Sculptors are regarded as artists, whereas carvers are viewed as artisans. These distinctions can be useful when considering a maker's self-perception, patronage, and intent, but they are almost useless in assessing quality. Although such judgments are inherently subjective, they gain validity to the extent that they recapture the attitudes and contexts of period makers and their patrons. Despite the current trend among decorative arts scholars to refrain from making aesthetic judgments, and despite the fact that objects made at different times or by different cultures cannot fairly be evaluated side by side, comparisons can and should be made between similar artifacts, just as they always have been. The concept that "you get what you pay for" was clearly prevalent among consumers in the past. A sideboard table whose origin has been debated for decades illustrates these points (fig. 1). Carved by Martin Jugiez during his partnership with Nicholas Bernard, this object is as much a work of sculpture as a piece of furniture. As the product of an atypical commission and an exceptionally talented artisan, the table challenges established notions of colonial American art and craft.[1]

The first widely published speculation that the sideboard table was American appeared in the June 1954 issue of Antiques. A column titled "In the Museums" reported that "an elaborately carved walnut side table with Sienna marble top . . . [had] recently been put on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art." Found in the Pennsylvania Hospital in 1926, the table "was for many years lent to the Museum and stood in the hall of Mount Pleasant in Fairmont Park" (fig. 2). The writer, Joseph Downs, chief curator for the Winterthur Museum, had observed:

The table is at once reminiscent of the lion period of 1730 in England; its massive proportions, combined with the lion-mask on its serpentine shaped apron and animal claw feet, point to the early Georgian period. At the same time, the lighter touches of rocaille ornament, flowering sprays and festoons are identical to those appearing in Chippendale's Director, especially the third edition of 1762. It is the subtle combination of these latter elements, to be observed repeatedly in Philadelphia furniture, as well as the discrepancy of date between these . . . details and the heaviness of the general design that points conclusively to its having been Philadelphia-made rather than English.

Downs did not cite any tangible evidence for his attribution, and subsequent opinion about the table has fluctuated greatly. It has been hailed as a masterpiece, considered out of period, exhibited as a Philadelphia icon, relegated to storage, loaned to City Hall as a furnishing prop, attributed to England or Ireland, and reattributed and published as Philadelphia. In the 1999 exhibition catalogue Worldly Goods: The Arts of Early Pennsylvania, 1680-1758, Jack Lindsey reported that the table was "commissioned about 1751-52 by Joshua Crosby, the first president of Pennsylvania Hospital and presented to the . . . building in 1755." While Lindsey was correct in attributing this object to Philadelphia, the dates cited by him are too early to have referred to the sideboard table. Jugiez does not appear in Philadelphia records before 1762, and the earliest carving associated with him dates no earlier than the late 1750s. Moreover, the table bears no relationship to work associated with Bernard or any of his early contemporaries.[2]

Nicholas Bernard's Training and Early Career

Evidence suggests that Nicholas Bernard either trained with or worked in the shadow of Samuel Harding, one the most important carvers active in Philadelphia during the first half of the eighteenth century. The benchmark for Harding's work and that of other artisans influenced by him is architectural carving in the Pennsylvania State House, known today as Independence Hall (fig. 3). The State House was one of the most important building projects undertaken in colonial Philadelphia.[3]

Construction of the stair tower, where much of the architectural carving survives, began in 1749/50. Seven years later Harding submitted a bill for more than £195.13.11 worth of carving, although he began furnishing ornaments by 1753. His shop provided 400 feet of molding, 146 banisters, 76 floral appliqués, 58 stair brackets, 33 leaf appliqués, 32 trusses, 30 capitals, 29 garlands, 8 flame finials, 6 stair posts, 5 friezes, 4 angles, 2 tabernacle frames, 2 pediment frames, and 2 keystones with "faces." The most ornate appliqués listed in his bill were installed in the stair tower (fig. 4). Composed of a central flower flanked by C-scrolls, leaves, and husks, these appliqués resemble those on a seminal group of Philadelphia case pieces from the 1740s. Harding's carving in the State House is much more typical of work from this decade than that from the 1750s. This should come as no surprise given the fact that construction of the State House began during the 1730s, and architectural carving and furnishings for public buildings tended to be conservative. The appliqués in the stair tower are also related to the carving on a larger, and possibly earlier, appliqué over the tabernacle frame in the Assembly Room (figs. 5, 6). The only other artisan who submitted a bill for carving in the State House was Brian Wilkinson. He probably trained with his father, Anthony, who was active in Philadelphia by 1720.[4]

The earliest work attributed to Harding appears to date from the 1740s and includes the carving on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in figure 7. The rosettes and acanthus match those in the stair tower of the State House (figs. 4, 8), and the tympanum shell is a slightly smaller version of the one on the frieze appliqué in the Assembly Room (fig. 5). William Kent and other Palladian designers employed similar shells, which were apparently derived from collected specimens. John Vardy illustrated one in a design for an organ case (fig. 9) in his influential book, Some Designs of Mr. Inigo Jones and Mr. William Kent (1744). As the carving on the desk-and-bookcase suggests, Harding appears to have been an immigrant fluent in the fashionable London mode of the 1720s and 1730s. The maturity of his earliest Philadelphia work indicates that his design vocabulary developed at the bench during his training rather than having been inspired by published sources. Through his own work and that of artisans he trained and influenced, Harding had a profound impact on Philadelphia carving styles. His high-relief central shell with flanking sprays of acanthus leaves remained the dominant composition for Philadelphia tympanum appliqués through much of the 1760s, and his relief-carved shell with flanking acanthus defined the concept of the shell drawer through the eighteenth century.[5]

Harding's influence is evident in a tympanum appliqué attributed to Nicholas Bernard (fig. 10). Although the shell is different from that on the pediment of the preceding desk-and-bookcase, the acanthus leaves flanking it are obviously based on those illustrated in figures 4 and 8. In addition to compositional similarities, the imprint of Harding's vocabulary is also apparent in Bernard's outlining and shading cuts. The tympanum appliqué probably dates from the late 1740s based on its relationship to the ornament on a Franklin stove (fig. 11) apparently cast tween 1742 and 1748 (fig. 12) and the carving on the high chest illustrated in figures 13-15. The cabinet shop responsible for this chest was active in Philadelphia by the early 1730s, producing cabriole-leg furniture with carved "Spanish feet" and scrolled skirts with strong Irish overtones. Bernard's work is also found on a slightly later high chest and matching dressing table (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation) signed "Henry Cliffton/Thomas Carteret" and dated November 15, 1753.[6]

By the late 1740s the stylistic vocabulary established by Harding must have seemed confining to the younger generation of Philadelphia carvers. To capture the imagination of their clients, they entered into a period of exuberant experimentation. This "early spring" of the Philadelphia rococo cannot accurately be called "Chippendale" since it occurred before the publication of the Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker's Director (1754) and remained linked to earlier styles. Its influences were imports-furniture, silver, engravings, and other media-rather than published designs.

A side chair from a set that reputedly descended in the Lambert family of New Jersey shows Bernard working in this new mode (figs. 16-18). The chair is covered with leaves, flowers, and other naturalistic ornament, but the frame is essentially early Georgian and the feet are akin to those first produced during Harding's era. Decorative arts scholars have traditionally dated the Lambert chairs much too late. They clearly predate the more popular shell-eared chairs carved by Bernard during the mid- to late 1750s (fig. 19).

Bernard's style emphasized the control of line over the sculpting of mass. A Lambert chair could be expressed almost completely in a drawing. The same approach is evident in the carving on three similar sideboard tables (figs. 20-22) and a turret-corner card table attributed to Bernard (fig. 23). When viewed from a distance, the contrast between the carved background and foreground elements of the rails is nearly imperceptible and the surface simply appears complicated. The effect is rich, but not clear. Because this work was less about carving than drawing, it did not fully exploit its medium-a fact that is clear from comparison of Bernard's work with the ornament on a card table attributed to the "Garvan high chest carver," which is visually graphic and powerful (fig. 24). Judging from the scarcity of surviving examples, Bernard's extremely opulent mode was not widely embraced by Philadelphia consumers. This is not to say that he was unsuccessful as an independent artisan. On the contrary, he did contract carving in a less ornate manner for an enormous group of chairs, tables, and case pieces made from the late 1740s to at least the late 1750s.[7]

Several objects attributed to Bernard have well-integrated incised and relief ornament. The intaglio carving on the demilune sideboard table shown in figure 25 carries the curved lower line of the rails up to frame the reserve above the knee where the incised husks redirect the line to the knees below (fig. 26). In general, Bernard's relief carving reads much better when it is set against a plain ground than against an articulated surface, like that on the rails of the aforementioned sideboard tables and card table. Througout his career, Bernard relied on his mastery of line and his ability as a draftsman to resolve design problems and accommodate the changing tastes of his clients.

Bernard's mature working style is reflected in the carving on the chest-on-chest illustrated in figure 27. His designs and techniques were well integrated, and he worked intuitively, efficiently, and quickly. The stiff gestures found in his earliest work are gone, the formerly awkward transition from the shell to the acanthus has been resolved, and the leaves are skillfully modeled with realistic twists and turns (see figs. 10, 28). Bernard occasionally used a modified version of this shell-and-acanthus design as an ornament for sideboard table façades (fig. 29). The cartouche ornament is similar to those found on several case pieces attributed to Bernard. These ornaments, which were probably laid out with a pattern, are the most sculptural work associated with Bernard.

A high chest and matching dressing table that appear to date from the late 1750s are among the latest furniture with carving attributed to Bernard. The knees, shell drawers, and feet are his work (figs. 30-33), but the tympanum appliqué is obviously by a more confident and skilled hand. The appliqué is cut from a single board rather than being composed of three separate pieces (center shell and right and left acanthus elements; fig. 33). Although it gives the impression of bilateral symmetry, it appears to have been drawn freehand with only a centerline and the shape of the tympanum as references. Carved rapidly and assuredly, the appliqué differs significantly from those associated with Bernard and other carvers influenced by Samuel Harding. Someone new was in town.[8]

Martin Jugiez

Bernard's stylistic vocabulary had become relatively entrenched by the mid-1750s. Although he had previously received the patronage of many Philadelphia consumers and artisans, as a working carver he had little impact on the further development of the rococo. Other tradesmen, particularly the "Garvan high chest carver," had captured the market. Bernard apparently stopped carving by the early 1760s and focused almost entirely on managerial tasks and marketing. The catalyst for this change was Martin Jugiez. Although his origin and even the spelling and pronunciation of his name remain a mystery, Jugiez was undoubtedly an immigrant. The earliest carving attributed to him indicates that he arrived with a fully developed working style that differed significantly from any established Philadelphia mode.[9]

No European furniture carving related to Jugiez's Philadelphia work has been identified. It is possible that he apprenticed with a master who specialized in house, ship, coach, or stone carving. An artisan with Jugiez's talent could, with the right connections, have found employment almost anywhere in the Western world. The lack of readily identifiable antecedents and the novel quality of his work might be explained if he had worked on the Continent before immigrating to Philadelphia. Except in rare instances when Jugiez was copying another carver's design, his work is not derivative of anything.

The precise date when Jugiez arrived in Philadelphia is not known. By the winter of 1762, he and Bernard had established their partnership and begun offering "all sort of Carving in Wood or Stone." In November of that year, the Pennsylvania Gazette reported: "Just imported . . . from London, and to be sold by BERNARD and JUGIEZ . . . at their Looking-Glass Store on Walnut-Street between Front and Second-Streets . . . A Compleat assortment of Looking-Glasses, framed in the newest Taste, Picture Frames, Sconces, Chimneypieces, Ornaments for Ceilings, Pictures Framed and Glazed, [and] a neat Harpsichord." This advertisement describing a well-stocked store with credit abroad suggests that the partnership had been established for some time.[10]

The impact of Jugiez's arrival and the differences between his and Bernard's styles are demonstrated by two chairs made in the same shop (figs. 34, 36). The side chair illustrated in figure 34 dates from the late 1750s and has knees with bilaterally symmetrical leaves separated by a V-shaped dart articulated with intaglio lunettes (fig. 35). Bernard frequently used this design for the knees of chairs, case furniture, and tables (see figs. 18, 30, 31). His carving is typically workmanlike, but not exceptional. In contrast, the chair carved by Jugiez (fig. 36) seems an entirely new species. The asymmetrical cartouches on the crest and seat rail have a three-dimensional quality rarely encountered on Philadelphia seating furniture (fig. 37).

Jugiez and the journeymen and apprentices he supervised appear to have been responsible for nearly all of the carving produced during his partnership with Bernard. Two high chests from the same shop as the matching high chest and dressing table illustrated in figures 30 and 31 date from the early 1760s, and Jugiez did all of their carving. By that time, Bernard was deeply involved in selling the firm's carving as well as looking glasses, furniture, and smaller decorative items they imported. During the 1760s he traveled to Boston, New York, and Charleston, placing similar advertisements in the leading newspapers of each city. Bernard evidently met with some success, since architectural carving by his and Jugiez's firm is found in houses as far south as New Bern, North Carolina. This business arrangement had distinct advantages for both men. Bernard profited from Jugiez's abilities as a designer and from his enormous skill and productivity, while Jugiez benefited from the local connections Bernard had made in his earlier career.[11]

Bernard and Jugiez worked for several of the city's leading furniture makers, including Benjamin Randolph, Thomas Affleck, and William Wayne. The carving on the chest-on-chest illustrated in figure 38 was probably contract work commissioned by a cabinetmaker, but the patron remains unidentified. Like all of Jugiez's relief-carved shells, the one on the upper drawer was derived from those carved by Bernard (figs. 32, 39). Jugiez simply used a different sequence of cuts to establish the outline and inserted his own flower and leaf elements in the center. His finials were also inspired by Bernard's, with each of the flame's three elements undulating in a continuous serpentine line. Jugiez's approach to the design of a tympanum appliqué in conjunction with a shell drawer is, however, a marked departure from that of his partner. Bernard's compositions tend to be clogged and repetitive (fig. 28), whereas his partner's designs achieve a more unified result. On the chest-on-chest, Jugiez's scrolls create a theater for his naturalistic elements (fig. 39). His use of tightly coiled scrolls at the bottom of the appliqué creates tension in the negative space and visually lifts and integrates the drawer.[12]

Jugiez produced a wide range of tympanum appliqués; however, there is no evidence that he used patterns (fig. 40). His speed, confidence, and capacity to work three-dimensionally are evident in his long modeling strokes, which often change direction, and bold undercutting (figs. 57, 58). Often Jugiez's cuts removed an astonishing amount of wood, which makes his work appear reckless to the modern eye. Jugiez invariably exploited the full thickness of his stock, working all the way from front to back. Even when doing relief carving, his approach was to mimic an appliqué. He would quickly drop the ground around his design to create an effect in solid stock resembling cut-card work in silver.

Whereas Bernard can be seen as a professional carver with a linear style, his partner was conceptually a sculptor. Jugiez had a profound understanding of how the individual section of carving he was working on would relate to the whole and how his work would look when viewed from a distance. As Thomas Sheraton noted:

It requires some command of the mind, for the carver to work so close as to suit considerable height or distance; in which case, his eye . . . must not govern him . . . but his judgement must take the lead, and constantly suggest to him the folly of finishing, in a tender manner, those flowers, and foliage . . . which are only to be viewed at a distance.[13]

Jugiez was obviously capable of producing fine detail, but expressive gestures and expediency were his main concerns. On several of his appliqués, he used one small gouge to detail one side and a different one for the other side. Jugiez presents a standard of craftsmanship at odds with the modern notion that the more time that is spent in making an object, the more precious the result.

The appliqué that Jugiez carved for the chest-on-chest illustrated in figure 38 is similar to one on a Philadelphia tall case clock with a movement by William Addis (figs. 39, 41, 42). The carving on the hood frames the arch in much the same way that the appliqué on the chest-on-chest frames the shell drawer. Both appliqués have deeply carved and pierced acanthus leaves in the center, a motif that Jugiez used repeatedly in furniture and architectural work. The leaves on the clock were sculpted with powerful modeling cuts, then shaded with minimal concern for finish detail.

The cabinet shop that produced the Addis case apparently had an in-house carver but commissioned work from specialists based on client demand. As the recently discovered Prices of Cabinet and Chair Work (1772) reveals, some Philadelphia carvers received set fees for standard ornaments for furniture supplied by cabinetmakers and merchants. Within the constraints of piecework contracting, carvers could increase their income only by working faster. As a consequence, they developed rapid but acceptable shorthand styles. Jugiez had the ability to tailor his style to suit his clients' tastes and budgets, from the most high-concept commission to the most time-pressured piecework.[14]

Jugiez's range of work is illustrated by three sets of chairs. In many respects, the ornament on the side chair illustrated in figure 43 is more akin to architectural carving than standard relief work on furniture. This is most clearly seen in the extreme depth of the acanthus leaves at the center of the crest rail and on the knees. The back and front legs were copied from a design for a side chair illustrated on plate 12 in the first and second editions of Thomas Chippendale's The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker's Director (1754, 1755) (fig. 44). Jugiez's chair is more sculptural than its prototype. Its cabriole legs have greater mass and more powerful sweep, their curve accentuated by deeply carved scrolls and leaves. In a departure from the Director design, the cabochons and leaves circling the scrolls of Jugiez's feet are pierced, undercut, and carved completely in the round (fig. 45). They attest to the tremendous control he maintained over his tools and material while working quickly. In a similar fashion, he carved the shell ears of the crest and small acanthus clusters flanking the lower piercing of the splat so deeply that he nearly reached the back of his stock (figs. 46, 47).[15]

Jugiez expended much less effort on another set of chairs with backs based on the same Director engraving (fig. 48). The modeling and shading of the shells and leaves on the crest and splat are in much lower relief than the corresponding details of the scroll-foot chair (fig. 49). The purchaser of the simpler set was operating in the piecework system, and his choice of cabriole legs with shallow acanthus carving and claw feet reflected local taste. He probably paid only slightly more than he would have for a standard chair with a carved splat. In contrast, the patron who commissioned the scroll-foot chairs wanted seating that was unmistakably London in character and was willing to pay more for Jugiez's fully developed interpretation of Chippendale's design. Another chair with ornament attributed to Jugiez (fig. 50) represents an even more vivid departure from the commissioned carving on the scroll-foot chair. Jugiez's handling of the crest and knee ornament reflects the pressures of a piecework system in their poorly conceived design and slipshod execution (fig. 51).

Like most of their competitors, Bernard and Jugiez's shop furnished architectural carving for public buildings and the homes of the city's elite. They provided a variety of components for St. Peter's Church (1763), Mount Pleasant (1764), Cliveden (1766), and the town houses of Samuel Powell (1769) and John Cadwalader (1771). The organ case in St. Peter's Church (figs. 52-54) and the major chimneypiece trusses and appliqué in the second-floor drawing room of Mount Pleasant (figs. 55, 56) are the most elaborate architectural work attributed to Jugiez. The pipes of the organ are crowned with large C-scrolls and complex leaves that are deeply modeled and heavily undercut (fig. 53). On the case below are elaborate floral garlands suspended from bows and tattered acanthus leaves (fig. 54) that resemble those at the top of the chimneypiece appliqué in Mount Pleasant (figs. 55, 56). The organ case may be a year or so later than the carving in St. Peter's. If so, the ornament on it may have been carved in the same year as the work in Mount Pleasant, which was completed in the fall of 1764.[16]

The woodwork in Mount Pleasant is documented to Thomas Nevell, a builder who learned his trade in Philadelphia and worked on the Pennsylvania State House. Nevell may have been responsible for the design of several details that Jugiez carved for Mount Pleasant. The small floral appliqués on the chimneypiece (fig. 57) appear to have been derived from an example recommended for the Doric order in Abraham Swan's British Architect (1745). In characteristic fashion, Jugiez undercut the flowers very deeply (fig. 58)-so much so that only two of these fragile components have survived. Although long since removed, the large appliqué between the chimneypiece trusses may also have had elements inspired by Swan's designs (fig. 59). A longer and more complex version attributed to the "Garvan high chest carver" was originally installed in Whitby Hall, another house with woodwork attributed to Nevell (fig. 60). The Whitby Hall appliqué has bird heads grasping acanthus leaves in their beaks, a detail found on one of Swan's stair bracket designs. Witness marks for the appliqué in Mount Pleasant suggest that it had bird heads adjacent to a pierced center shell.[17]

A fireback pattern that Jugiez carved for ironmaster Isaac Zane in Winchester, Virginia, required as much, if not more, skill than most of his architectural work (fig. 61). On December 20, 1770, Zane's brother-in-law John Pemberton paid Bernard and Jugiez the considerable sum of eight pounds "for the Arms of Earl of Fairfax for a Pettern for the back of a chimney." Although the casting shows the lion in profile, the animal's mane, forehead, eyes, and nose are virtually identical to those of the lion on the sideboard table (fig. 1). The naturalism and depth of this casting are particularly impressive when one considers that Jugiez had to avoid undercuts that would prevent the pattern from cleanly drafting out of the foundry sand. Even when working in this imposed low relief, Jugiez's sculptural capacity was remarkable. The horse and lion read as actual creatures rather than representations, whereas their counterparts on British firebacks are typically abstract and considerably more shallow.[18]

Bernard and Jugiez's advertisements indicate that they produced other coats of arms that were either larger or more elaborate than those depicted on the Fairfax casting. In the October 12, 1765, issue of the South Carolina Gazette, Nicholas Bernard advertised "the Kings Coat-of-Arms carved in wood, suitable for a State House or Court-House." Armorials must have been a stock item for their firm since they placed similar notices in other colonial newspapers. Bernard's marketing evidently met with some success. In February 1768 the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly approved the payment of £73.10 to him for the "King's Arms in the Council Chamber." This represented approximately £17.17 in Philadelphia currency and was more than twice the cost of the pattern for the Fairfax fireback.[19]

At least three finial busts of English philosopher John Locke can also be attributed to Jugiez based on the modeling of their facial features and hair. The most realistic example (fig. 62) was made for an elaborate Philadelphia desk-and-bookcase with a pitched pediment and a pierced, leaf-carved tympanum. This bust has extremely naturalistic facial contours, well-defined nose and lips, and eyes with heavy lids-features found on the best contemporary ceramic and plaster versions of Locke. Like most figural busts produced by eighteenth-century Philadelphia carvers, Jugiez's were probably derived from imports. In 1765 he and Bernard advertised a "variety of neat figures and busts in plaister of Paris, with brackets for ditto."[20]

The Lion Table: Art or Craft?

Martin Jugiez's creative capacity is most evident in the sideboard table illustrated in figures 1 and 63, perhaps the most sculptural piece of colonial American furniture. Its dynamic form and startling muscularity required enormously heavy stock. The front legs were cut from mahogany beams eight inches square, and the front rail was formed from similar stock with laminates making the center 14 inches high and 10⁄÷™ inches thick (fig. 64). The construction of the table resembles heavy timber framing, indicating that it is not the product of a cabinet shop. All of the primary stock was sawn and, remarkably, hewn prior to fabrication (fig. 65); the only planed surfaces are on the front rail behind the laminates and the rear rail. To assemble the frame, the maker used eight large mortise-and-tenon joints and secured them with enormous half-inch pins. This hastily framed structure was not intended to form a skeleton; it was simply a means of providing Jugiez with sufficient material—a mass that he sawed, hacked, and carved until the table emerged (fig. 66). By the time the table was completed, Jugiez had removed more wood than remained. This approach is traditional for reductive sculpture.

The carving on the lion table provides conclusive evidence that it is a product of Jugiez's hand. The scrolls and leaves on the front knees are high-relief versions of those on the chimneypiece trusses in the second-floor parlor of Mount Pleasant (figs. 67, 68). Beneath both sets of leaves are naturalistic swags of leaves, flowers, and buds-details that Jugiez also used on the chimneypiece trusses in Cliveden and the organ case in St. Peter's Church (fig. 54). Similar elements also appear on the urn-and-flower ornament and quarter-columns of a matching high chest (figs. 69, 70) and dressing table attributed to him. Likewise the confronting C-scrolls on the front rails of these two case pieces are an analogue of those framing the lion's head (figs. 71, 72). In modeling the lion's brow, Jugiez used shallow gouges with the blade turned upside down. The same approach is evident in his sculpting of the forehead on the Locke bust (fig. 62) and facial contours of the lion on the Fairfax fireback (fig. 61). The gestures of Jugiez's figural subjects are invariably bold and animated.

Both the form and ornamental composition of the table are distinctive, and everything about it is indicative of a commissioned object. From a design standpoint, the table is a hybrid of a conventional sideboard table with four legs and a console table with dramatically receding front legs. The rear legs mimic the front ones in their movement off plumb and toward the center of the table (fig. 73), a feature that occasionally is found on eighteenth-century Italian examples. The marble top imposed the only limitation on the lion table's plan, dictating the basic shape, width, and depth of the rails. Patrons typically purchased finished slabs before commissioning their frames, since the cost of marble often exceeded the cost of the frame that supported it. The distinctive shape of the marble on the lion table recalls the inventory of London cabinetmaker William Linnell (d. 1763) whose shop contents included "2 marble Siena slabs, sweept in the French taste."

A pencil drawing of a sideboard table attributed to Matthias Lock (ca. 1740-1770; fig. 74) and an ink-and-wash drawing of another example attributed to William (ca. 1703-1763) or John Linnell (1729-1796; fig. 75) relate to Jugiez's table, but both designs were intended for construction using standard cabinetmaking techniques. This is particularly evident in Lock's drawing, which depicts a conventional rectangular frame with an applied frieze and legs joined at right angles. The table in the Linnell drawing is much closer to Jugiez's in the scale of its legs, reticulated rail, and C-scrolls framing its large lion's head.[21]

Many British tables of this genre were influenced by the designs of Palladian architects like William Kent, who were familiar with northern Italian furniture styles of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. An Italian sideboard table similar to the one shown in figure 76 or a British derivative could have provided inspiration for both Linnell's and Jugiez's designs, but the latter's table is largely the product of his imagination (fig. 63). Many examples of courtly European furniture have carving as accomplished as that on the lion table, but few can match its animated and expressive power. Jugiez apparently conceived the entire object as the embodiment of a lion rather than a table decorated with a lion's head. Although clearly functional, the table looks as though it is ready to pounce. There can be little doubt that Jugiez was attempting to create something outside the context of contemporary Philadelphia design, an object that fulfilled his patron's expectations while allowing him to exploit fully his talents as a designer and a carver. For American artisans deprived of courtly sponsorship, the distinction between art and craft depended on opportunity.[22]

Little is known about Bernard and Jugiez's work during the Revolutionary War, but by 1783 they were operating separate businesses. The Philadelphia tax assessment for that year listed Bernard as a shopkeeper in the South Ward and Jugiez as a carver in the Middle Ward. It is possible that Bernard continued to manage Jugiez's business, just as he had in previous years. The bonds of friendship that formed during their partnership clearly persisted. When Bernard signed his last will and testament in 1789, he requested that his family care for Jugiez if he became "necessitated." Jugiez died in 1815, leaving $100 to his nephew Jerome and the remainder of his estate to "my beloved Friend John Bernard [Nicholas's son] and his Heirs."

During the late 1750s Samuel Harding died, William Rush was born, and Martin Jugiez immigrated. This confluence marked the end of the first generation of Philadelphia carving, the birth of one of the most celebrated artists of the new republic, and the arrival of an ingenious carver who bridged the two eras. Apparently the only major carver of the Philadelphia rococo to survive the yellow fever epidemics and the onset of the federal style with both his life and livelihood intact, Jugiez continued to ply his trade into the new century. Simultaneously, Rush emerged from his training as a ship carver and became an important public figure, considered by some to be America's first sculptor. But does his work really demonstrate the uncanny ability to think and work in three dimensions manifest in the most sculptural work by Martin Jugiez? To fairly address this question, the lion table must be summoned as a witness.[23]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article the authors thank Glenn Adamson, Philip Bradley, Dudley and Constance Godfrey, Fred Hoover, Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley, Jerold D. Krouse, Rob McCullough, David deMuzio, Susan Newton, Philip Ruhl, Robert Trent, and the institutions and collectors who generously allowed us to study and photograph their objects. We are especially grateful to the late Marjorie Miller for her love, support, and interest in this project.

Although modern decorative arts scholars often criticize aesthetic studies such as Albert Sack’s Fine Points of Early American Furniture, which places objects under the categories of “good,” “better,” and “best,” this approach is not entirely without merit (Sack, Fine Points of Early American Furniture [New York: Crown Publishers, 1950]). The turned great chairs illustrated on p. 13 of Sack’s book are an excellent case in point. All were made in New England at approximately the same date, and all are from a predominantly Anglo-American cultural context. The turner who produced the chair identified as “best” was considerably more skilled than the makers of the “good” and “better” examples. Skill and workmanship have always been important considerations for consumers. Artisans who made things that were poorly designed or badly constructed rarely prospered in their trade (see Eleanore P. Gadsden, “When Good Cabinetmakers Made Bad Furniture: The Career and Work of David Evans,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite [Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2000], pp. 65–88). Sack’s assertion that a Rhode Island block-front chest with carved shells is better than a Massachusetts block-front without shells is not valid since the objects were made in different cities for patrons with different cultural backgrounds and tastes (Sack, Fine Points, p. 103). For more on Bernard and Jugiez, see Luke Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops Part II: Bernard and Jugiez,” Antiques 128, no. 3 (September 1985): 498–513.

“In the Museums” in Antiques 65, no. 6 (June 1954): 498. Bill from Belfi Bros. to Pennsylvania Museum of Art, June 30, 1926, for “removing . . . top [from the lion table], repairing and furnishing new marble necessary [for repairs].” The Philadelphia Museum of Art paid for the restoration in exchange for the loan of the table from the Pennsylvania Hospital. In 1949 the hospital sold the table to Carl M. Williams who was acting as an agent for Lawrence J. Morris (James Sommers Smith to Fiske Kimball, November 10, 1949; and M. T. Wright Jr. to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, November 14, 1949). Joe Kindig Jr. apparently purchased the table from Morris’s estate and subsequently sold it to the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Accession file, Philadelphia Museum of Art). Philip B. Wallace, Colonial Houses: Philadelphia, Pre-Revolutionary Period (New York: Architectural Book Publishing Co., 1931), p. 157. Jack Lindsey et al., Worldly Goods: The Arts of Early Pennsylvania, 1680–1758 (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1999), p. 150. Lindsey does not cite a source for Crosby’s gift, and the authors have found no evidence that the table was in the Pennsylvania Hospital during the eighteenth century.

For more on the construction of the State House, see Edward M. Riley, “The Independence Hall Group,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 43, no. 1 (March 1953): 7–25; Beatrice Garvan, “The State House (Independence Hall),” in Philadelphia: Three Centuries of American Art (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1976), pp. 41–42. For Harding, see Luke Beckerdite, “An Identity Crisis: Philadelphia and Baltimore Furniture Styles of the Mid Eighteenth Century,” in Shaping a National Culture: The Philadelphia Experience, 1750–1800, edited by Catherine E. Hutchins (Winterthur, Del.: Winterthur Museum, 1994), pp. 250–75. In 1735 Philadelphia house joiner Edmund Wooley billed John Penn £5 for elevations and floor plans for the State House. Wooley was about ten years old when his family emigrated from England in 1705. Although his apprenticeship remains a mystery, both the form and detail of the State House attest to his knowledge of early-eighteenth-century British architectural styles. Engravings from Colin Campbell’s Vitruvius Britannicus and James Gibbs’s Book of Architecture (1728) are often cited as sources for his design, and both publications were available through the Library Company of Philadelphia (Garvan, “The State House,” pp. 41–42). Wooley’s training during the 1710s may account for the baroque aspect of certain exterior and interior details. The center hall has a heavy Doric entablature, fluted columns, and elliptical arches with raised panels and carved Indian heads. These details were probably installed about 1750, when the hall, Assembly Room, and Supreme Court Chamber were completed (Riley, “Independence Hall Group,” p. 17).

Riley, “Independence Hall Group,” p. 17. For case pieces with related appliqués, see Morrison H. Heckscher, American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art; II, Late Colonial Period: The Queen Anne and Chippendale Styles (New York: Random House, 1985), pp. 306–7, no. 198; Sack, Fine Points, p. 165 (center and bottom); and Beckerdite, “Identity Crisis,” p. 273, fig. 34. Wilkinson’s bill was submitted in 1756 and totaled £85.8.10. For more on the Wilkinsons, see R. Curt Chinnici, “Pennsylvania Clouded Limestone: Its Quarrying, Processing, and Use in the Stone Cutting, Furniture, and Architectural Trades,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), pp. 107–9.

For a preconservation view of this desk-and-bookcase, see Sotheby’s, The Collection of Mrs. Lamont du Pont Copeland, New York, January 19, 2002, lot 43. Harding is described as an immigrant because there is no Philadelphia antecedent for his work. Michael I. Wilson, William Kent: Architect, Designer, Painter, Gardener, 1685–1748 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984), p. 117, fig. 40. Kent used a similar shell for the headboard of a state bed at Houghton (p. 107, fig. 29). Harding’s vocabulary reflects his training, which presumably occurred in Britain during the 1720s and/or 1730s. Immigrant carver Henry Hardcastle, who worked in New York and Charleston during the 1750s, was the most skilled American exponent of this style. For more on him, see Luke Beckerdite, “Origins of the Rococo Style in New York Furniture and Interior Architecture,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1993), pp. 15–39.

The other sideboard tables are illustrated in Charles Hummel, A Winterthur Guide to American Chippendale Furniture: Middle Atlantic and Southern Colonies (New York: Crown Publishers for the Winterthur Museum, 1976), pl. 14; and Sotheby’s, Property from a Private West Coast Collection, New York, December 4, 2003, lot 59. The entire body of furniture carving attributed to Bernard is too large to cite. For important pieces not illustrated in this article, see Loan Exhibition of Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Century Furniture & Glass . . . for the Benefit of the National Council of Girl Scouts (1929; reprint, New York: By the Council, 1977), no. 651 (high chest); William Macpherson Hornor, Blue Book: Philadelphia Furniture from William Penn to George Washington (Philadelphia: By the author, 1935), pls. 76 (card table), 102 (chest-on-chest), 131 (sideboard table), 142 (dressing table), 153 (high chest base), 182 (high chest), 183 (dressing table), 185 (dressing table), 193–94 (desk-and-bookcase), 232 (side chair), 234 (card table), 336 (side chair); Eighteenth-Century American Arts: The M. and M. Karolik Collection (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1950), no. 83 (side chair); Joseph Downs, American Furniture, Queen Anne and Chippendale Periods in the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum (New York: Macmillan Co., 1952), pls. 37 (armchair), 126–28 (side chairs), 185 (chest-on-chest), 271 (settee), 360 (sideboard table); F. Lewis Hinckley, Dictionary of the Historic Cabinet Woods (New York: Bonanza Books, 1960), p. 123, fig. 119 (high chest); Hummel, A Winterthur Guide to American Chippendale Furniture, possibly no. 103; Patricia E. Kane, 300 Years of American Seating Furniture: Chairs and Beds from the Mabel Brady Garvan and Other Collections at Yale University (Boston: New York Graphic Society for Yale University Art Gallery, 1976), no. 114 (side chair); Heckscher, American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, no. 51 (side chair); Christopher P. Monkhouse and Thomas S. Michie, American Furniture in Pendleton House (Providence: Rhode Island School of Design, 1986), no. 110 (side chair); J. Michael Flanigan, American Furniture from the Kaufman Collection (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1986), pp. 24–25 (side chair), 26–27 (side chair), 86–89 (high chest and matching dressing table); Treasures of State: Fine and Decorative Arts in the Diplomatic Reception Rooms of the U.S. Department of State, edited by Alexandra W. Rollins (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1991), nos. 18 and 19 (high chest and dressing table shells, rail appliqué, and legs—all other carving modern), 31 (pair of side chairs), 68 (pillar-and-claw tea table); David Warren et al., American Decorative Arts and Paintings in the Bayou Bend Collection (Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1998), no. 119 (sideboard table, mate to fig. 25), no. 132 (high chest); Deborah Anne Federhen, “Politics and Style: An Analysis of the Patrons and Products of Jonathan Gostelowe and Thomas Affleck,” in Hutchins, ed., Shaping a National Culture, p. 286, fig. 1 (chest-on-chest); Luke Beckerdite and Alan Miller, “Furniture Fakes in the Chipstone Collection,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), pp. 81–82, figs. 55–57 (dressing table); Selections from the Collection of Vincent Dyckman Andrus (New York: Bernard & S. Dean Levy, 2004), cover, p. 22 (dressing table).

For preconservation views of the high chest and dressing table, see Sotheby’s, Highly Important Americana from the Collection of Stanley Paul Sax, New York, January 16–17, 1998, lot 522.

Pennsylvania Gazette, November 25, 1762.

Jugiez took Robert Doughery as an apprentice for a term of four years on May 15, 1773, and Daniel Fegan as an apprentice for a term of seven years, eleven months, and twenty-three days on April 30, 1773. Records of indentures of individuals bound out as apprentices, servants, etc.: and of German and other redemptioners in the office of the Mayor of the city of Philadelphia, October 3, 1771 to October 5, 1773 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1973), pp. 224–25, 218–19. Bernard may have continued to carve claw feet during his partnership with Jugiez. Formerly in the collection of John C. Toland, the high chest carved entirely by Jugiez is illustrated in Edgar G. Miller Jr., American Antique Furniture: A Book for Amateurs, 2 vols. (1937; reprint, New York: Dover, 1966), 1: 376, no. 660. The ornaments, rosettes, and finial shown on the Toland chest are new, and the backboards of the pediment are missing. The other high chest is in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. It is illustrated in Loan Exhibition of Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Century Furniture & Glass . . . for the Benefit of the National Council of Girl Scouts, no. 658. Mabel M. Swan, “Boston’s Carvers and Joiners,” Antiques 53, no. 3 (March 1948): 201; Rita Susswein, “Pre-Revolutionary Furniture Makers of New York City,” Antiques 25, no. 1 (January 1934): 36; South Carolina Gazette, October 12, 1765.

Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops Part II.” On August 4, 1771, Nicholas Bernard took a “note of hand for forty pounds payable in Six Months” from Randolph (Benjamin Randolph Receipt Book, 1763–1777). Thomas Affleck’s bill to John Cadwalader for furniture made between October 10, 1770, and January 14, 1771, includes charges of £37 to “Mr. [James] Reynolds for Carving the Above” and £24.4 to Bernard and Jugies “Ditto for Ditto.” This bill is illustrated in Nicholas B. Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur in Philadelphia: The House and Furniture of General John Cadwalader (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1964), p. 44. A high chest by William Wayne has carving attributed to Jugiez (Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops Part II,” pp. 508–10, figs. 20, 20a, 20b).

Thomas Sheraton, The Cabinet Dictionary, 2 vols. (1791; reprint, New York: Praeger Publishers, 1970), 1: 134.

For examples of the in-house carver’s work, see Heckscher, American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 307–8, no. 199; and David Conradsen, Useful Beauty: Early American Decorative Arts from St. Louis Collections (St. Louis: St. Louis Museum of Art, 1999), pp. 80–81. A case from this same shop with carving attributed to the London immigrant carver John Pollard is illustrated in William H. Diston and Robert Bishop, The American Clock (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1976), pp. 20–21. Prices of Cabinet and Chair Work (Philadelphia: James Humphreys, 1772). The only known copy of this book is in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Several copies of this influential publication were in Philadelphia during the period. Bernard and Jugiez’s occasional client Thomas Affleck may have brought a copy of the Director to the city when he emigrated from London in 1763. His 1794 estate inventory listed “Shippendale’s Designs.” For more on Chippendale’s Director and its use in Philadelphia, see Morrison H. Heckscher, “English Furniture Pattern Books in Eighteenth-Century America,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1994), pp. 185–88.

Abraham Swann, The British Architect (1758; reprint, London: Da Capo Press, 1967), pls. 4 (flower), 39 (bracket). The trusses of the chimneypiece in the first-floor parlor at Mount Pleasant appear to have been derived from those on the chimneypiece illustrated in pl. 50. Bernard and Jugiez also used similar trusses for a chimneypiece in Cliveden.

John Bivins Jr., “Isaac Zane and the Products of Marlboro Furnace,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 9, no. 1 (May 1985): 43–44. Bernard and Jugiez carved additional patterns for Zane. In March 1776 the ironmaster wrote Joseph Pemberton, “I should be glad to pay Bernard & Jugiez but I have not an exact account of the debt.” Bernard and Jugiez probably provided patterns for other furnaces. On June 22, 1772, Bernard acquired one-fifth interest in Martic Forge in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania (Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops Part II,” p. 512). The following year Jugiez and a Philadelphia tallow chandler named John Jackson provided security for a loan of £222.15.8 to James Haldane, a brass founder and coppersmith who moved from Philadelphia to Norfolk, Virginia (Norfolk County Deed Book 26, p. 132a, microfilm copy in the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Winston-Salem, N.C.).

South Carolina Gazette, October 12, 1765.

The egg-and-tongue molding and fluted frieze of Lock’s design suggest that he drew it about 1740, when he was still influenced by Palladian classicism and only beginning to experiment with the new rococo style. Another Lock drawing of about the same date depicts a sideboard table that is more classically inspired. The base of a table from Ditchley House (Temple Newsam, Leeds Art Gallery) matches the latter drawing. For more on these designs, see Peter Ward-Jackson, English Furniture Designs of the Eighteenth Century (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1958), pp. 38–41. Helena Hayward and Pat Kirkham, William and John Linnell: Eighteenth-Century London Furniture Makers, 2 vols. (New York: Rizzoli in association with Christie’s, 1980), 1: 1–5. William Linnell’s accounts indicate that sculptural carving was part of his shop’s repertoire. On October 8, 1740, he charged Richard Hoare £11.11 for “making and carving” a pair of mahogany card tables, “with lions heads [and vines] on the knees,” paw feet, and a front rail with festoons and a “Bacchanalians head” (p. 141). Hayward and Kirkham speculated that John Linnell became the principal designer in the firm by the mid-1750s (p. 20). The drawing illustrated in figure 75 may have been executed at about that time. The strong similarities between the Linnell drawing and Jugiez’s table raise several questions. Did Jugiez work in Linnell’s shop before immigrating to Philadelphia? Were engraved designs based on this drawing available in England or her colonies? Was the Linnell drawing based on an existing table that either Jugiez or his patron saw in England? Although the names of all the journeymen and apprentices who worked for the Linnells are not known, Jugiez’s work differs significantly from carving documented and attributed to their firm, or any other London shop, for that matter. No engraved furniture designs by William or John Linnell are known, nor is there any evidence in the historical record that they issued them. John Linnell did, however, produce conceptual drawings for his patrons and working drawings for journeymen and apprentices. Most of Linnell’s drawings were original designs, but some may have been copied or inspired by existing forms. If the drawing was based on an existing object, it would help explain why their firm was producing outdated furniture in the mid-1750s. Patrons occasionally commissioned old-fashioned furniture to fill in existing suites or replace damaged objects. The Linnells produced furniture and architectural ornaments with lion’s heads. On July 15, 1758, William charged the earl of Coventry £4.16 “for wood and joyners work to get out a chimney and carving the same very neat by drawing in the French taste with lions faces in the frieze £4.16.0” (ibid., p. 149).

Obviously, the production of the lion table required substantial patronage. It is easy to imagine it sitting in an important public building with a coat of arms suspended on the wall above or in the house of a wealthy Philadelphian who had seen a similar table while on the grand tour. Philadelphia merchant John Cadwalader and his wife Elizabeth (Lloyd) owned a marble-top table comparable to the one carved by Jugiez. The Cadwaladers’ table has elements taken from two designs in Chippendale’s Director, and its carving is attributed to John Pollard, an immigrant who worked for Benjamin Randolph before establishing his own shop. For more on this table, see Leroy Graves and Luke Beckerdite, “New Insights on John Cadwalader’s Commode-Seat Side Chairs,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2000), pp. 159–60.

Between 1797 and 1799 Jugiez supplied the Scamozzi Ionic capitals for pillars in the rotunda of the Pennsylvania Hospital (Beatrice B. Garvan, “Pennsylvania Hospital,” in Philadelphia: Three Centuries of American Art, p. 64).