C H I P S T O N E

Sam Margolin

“And Freedom to the Slave”: Antislavery Ceramics, 1787–1865

In February 1788 Josiah Wedgwood sent the president of the Pennsylvania

Society for the Abolition of Slavery “a few Cameos on a subject which is

daily more and more taking possession of men’s minds on this side of the

Atlantic as well as with you.” Accordingly, Wedgwood added “it gives me

great pleasure to be embarked on this occasion in the same great and good

cause with you, Sir.” The president of the Pennsylvania society was

Benjamin Franklin and the “great and good cause” to which Wedgwood

referred was the eradication of human bondage. [1]

Society for the Abolition of Slavery “a few Cameos on a subject which is

daily more and more taking possession of men’s minds on this side of the

Atlantic as well as with you.” Accordingly, Wedgwood added “it gives me

great pleasure to be embarked on this occasion in the same great and good

cause with you, Sir.” The president of the Pennsylvania society was

Benjamin Franklin and the “great and good cause” to which Wedgwood

referred was the eradication of human bondage. [1]

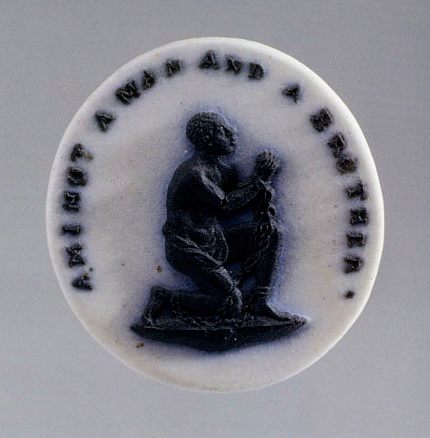

The jasperware cameos featured the image of a kneeling, black male slave

in chains, a design modeled by William Hackwood and adopted by the

Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1787 for use in its seal (fig.

1). Wedgwood reproduced the image for the founding of the society and

donated the cameos to friends and supporters of the cause.[2]

in chains, a design modeled by William Hackwood and adopted by the

Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1787 for use in its seal (fig.

1). Wedgwood reproduced the image for the founding of the society and

donated the cameos to friends and supporters of the cause.[2]

Wedgwood’s dedication to the antislavery movement developed in the

context of prevailing Enlightenment influences. He was closely associated

with the Lunar Society of Birmingham, composed of men who shared not

only a passion for scientific inquiry but also an interest in social and

industrial progress. In 1773 society member Thomas Day published The

Dying Negro, an epic poem which may have influenced Wedgwood to

become actively involved in suppression of the slave trade.

context of prevailing Enlightenment influences. He was closely associated

with the Lunar Society of Birmingham, composed of men who shared not

only a passion for scientific inquiry but also an interest in social and

industrial progress. In 1773 society member Thomas Day published The

Dying Negro, an epic poem which may have influenced Wedgwood to

become actively involved in suppression of the slave trade.

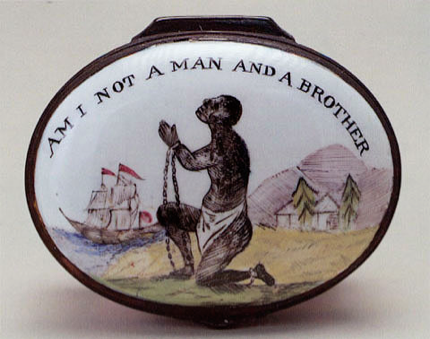

Thomas Clarkson, one of Britain’s leading abolitionists, indicated how the

cameos came to be widely disseminated, publicly visible, and a valuable

means of promoting the cause (fig. 2). Women, he reported, had them

incorporated into bracelets and hairpins so that eventually “the taste for

wearing them became general.” The medallions were also set into boxes,

and artisans applied the design to a variety of objects including plates,

pitchers, patch and snuff boxes, tea caddies, and tokens (fig. 3). “Thus

fashion,” observed Clarkson, “which usually confines itself to worthless

things, was seen for once in the honourable offce of promoting the cause of

justice, humanity and freedom.”[3]

cameos came to be widely disseminated, publicly visible, and a valuable

means of promoting the cause (fig. 2). Women, he reported, had them

incorporated into bracelets and hairpins so that eventually “the taste for

wearing them became general.” The medallions were also set into boxes,

and artisans applied the design to a variety of objects including plates,

pitchers, patch and snuff boxes, tea caddies, and tokens (fig. 3). “Thus

fashion,” observed Clarkson, “which usually confines itself to worthless

things, was seen for once in the honourable offce of promoting the cause of

justice, humanity and freedom.”[3]

African Images in English Society

Promoting the cause was a task made all the more diffcult, however, by the

less than complimentary manner in which blacks were often portrayed in

Anglo-American culture. Much of the negative attitude derived from the

specific and powerful meanings that English society associated with the

word “black” well before the introduction of Africans to England in the

1550s. Some pre-sixteenth-century definitions in the Oxford English

Dictionary including “deeply stained...dirty, malignant...foul, iniquitous,

atrocious, horrible, wicked,” exemplify decidedly negative connotations.

Consistent with this view, Queen Elizabeth I sought to banish blacks from

the kingdom in 1601, declaring her “discontent...at the great numbers of

negars and Blackamoors which...are crept into this realm.” [4] But the very

fact that the population of Africans (whose immigration to the country was

by no means voluntary) was increasing suggests that not everyone in

England was repulsed by their presence. In fact, blacks were gaining

popularity among the English gentry as domestic servants and status

symbols, a fashion trend that continued throughout the seventeenth and

most of the eighteenth centuries.

less than complimentary manner in which blacks were often portrayed in

Anglo-American culture. Much of the negative attitude derived from the

specific and powerful meanings that English society associated with the

word “black” well before the introduction of Africans to England in the

1550s. Some pre-sixteenth-century definitions in the Oxford English

Dictionary including “deeply stained...dirty, malignant...foul, iniquitous,

atrocious, horrible, wicked,” exemplify decidedly negative connotations.

Consistent with this view, Queen Elizabeth I sought to banish blacks from

the kingdom in 1601, declaring her “discontent...at the great numbers of

negars and Blackamoors which...are crept into this realm.” [4] But the very

fact that the population of Africans (whose immigration to the country was

by no means voluntary) was increasing suggests that not everyone in

England was repulsed by their presence. In fact, blacks were gaining

popularity among the English gentry as domestic servants and status

symbols, a fashion trend that continued throughout the seventeenth and

most of the eighteenth centuries.

Contemporary paintings of English aristocrats often included black

attendants, generally ascribing to the Africans a status comparable to that

of household pets. These graphic representations generally depicted the

servant either gazing earnestly at his or her white master or mistress or as

a “mute background figure...unnoticed and unacknowledged...barely more

than a blob of black paint, a shadowy figure with no personality or

expression.” [5] The black servants portrayed in mid-eighteenth-century

Staffordshire figural groups typically display unflattering, almost apelike

characteristics: protruding lower jaw, low and massive brow, and

exceptionally long arms (fig. 5). This diminished image of the black servant

was further reinforced by the mass production of the late eighteenth-

century transfer print of The Tea Party in which the features of the pet dog

appear to have been rendered with greater care than those of the black

houseboy (fig. 6).

attendants, generally ascribing to the Africans a status comparable to that

of household pets. These graphic representations generally depicted the

servant either gazing earnestly at his or her white master or mistress or as

a “mute background figure...unnoticed and unacknowledged...barely more

than a blob of black paint, a shadowy figure with no personality or

expression.” [5] The black servants portrayed in mid-eighteenth-century

Staffordshire figural groups typically display unflattering, almost apelike

characteristics: protruding lower jaw, low and massive brow, and

exceptionally long arms (fig. 5). This diminished image of the black servant

was further reinforced by the mass production of the late eighteenth-

century transfer print of The Tea Party in which the features of the pet dog

appear to have been rendered with greater care than those of the black

houseboy (fig. 6).

Africans in English society appear to have been as much objects of curiosity

and fascination as disdain, however. In addition to their appearance on

trade cards, maps, and coats of arms, figures of African adults and children

were employed on signboards, ubiquitous in eighteenth-century London, to

advertise occupations as varied as those of cheesemongers, haberdashers,

and oilmen. [6] The particular motifs of the blackamoor’s head (usually in

profile) and the black boy (or, occasionally, the black girl) have been

identified as characteristic of the linen drapers and pewterers, respectively.

Both designs also were widely used by tobacconists and public houses, or

pubs, as mention of the “Black Boy in Bucklersbury” tavern in Ben Jonson’s

early seventeenth-century play Bartholomew’s Fair suggests (Act 1, scene

1). [7] Such images may not have been quite as omnipresent in America, but

references such as the 1735 newspaper announcement of a Philadelphia

merchant relocating to Market Street under “the sign of the Black Boy”

indicate that they certainly existed (fig. 4).[8]

and fascination as disdain, however. In addition to their appearance on

trade cards, maps, and coats of arms, figures of African adults and children

were employed on signboards, ubiquitous in eighteenth-century London, to

advertise occupations as varied as those of cheesemongers, haberdashers,

and oilmen. [6] The particular motifs of the blackamoor’s head (usually in

profile) and the black boy (or, occasionally, the black girl) have been

identified as characteristic of the linen drapers and pewterers, respectively.

Both designs also were widely used by tobacconists and public houses, or

pubs, as mention of the “Black Boy in Bucklersbury” tavern in Ben Jonson’s

early seventeenth-century play Bartholomew’s Fair suggests (Act 1, scene

1). [7] Such images may not have been quite as omnipresent in America, but

references such as the 1735 newspaper announcement of a Philadelphia

merchant relocating to Market Street under “the sign of the Black Boy”

indicate that they certainly existed (fig. 4).[8]

While many of these representations were patronizing to various degrees,

not all were inherently derogatory or condescending. The use of African

images in conjunction with heraldic crests conveys a sense of dignity, even

nobility, conforming to contemporary European notions of the “noble

savage” (figs. 7, 8, 9 and 10). But whether portrayed as pet-like servants,

quaintly exotic figures, or noble savages, such depictions of Africans in

Anglo-American popular culture all failed to convey the harsh and often

brutal realities of chattel slavery in America and the West Indies (fig. 11).

not all were inherently derogatory or condescending. The use of African

images in conjunction with heraldic crests conveys a sense of dignity, even

nobility, conforming to contemporary European notions of the “noble

savage” (figs. 7, 8, 9 and 10). But whether portrayed as pet-like servants,

quaintly exotic figures, or noble savages, such depictions of Africans in

Anglo-American popular culture all failed to convey the harsh and often

brutal realities of chattel slavery in America and the West Indies (fig. 11).

Abolition Images

To persuade others of the rightness of their cause, abolitionists first had to

make a convincing case for the essential humanity of black people. Perhaps

it was for this reason that the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade

chose the specific wording “Am I Not a Man and a Brother” for use on its

seal and, consequently, Wedgwood’s cameo. Before Englishmen and

Americans could regard slaves as brothers, they would first have to

consider them human beings.

make a convincing case for the essential humanity of black people. Perhaps

it was for this reason that the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade

chose the specific wording “Am I Not a Man and a Brother” for use on its

seal and, consequently, Wedgwood’s cameo. Before Englishmen and

Americans could regard slaves as brothers, they would first have to

consider them human beings.

In the late eighteenth century, however, evangelical and Enlightenment

influences gave rise to a growing impulse toward humanitarianism and a

mood of sentimentality that produced greater empathy with the slave’s

plight.[9] Among the foremost literary efforts was William Cowper’s seven-

stanza poem The Negro’s Complaint, cited by Clarkson as an influential

popular work that spread throughout England “where it was sung as a

ballad; and where it gave a plain account of the subject, with an

appropriate feeling, to those who heard it.” [10]

influences gave rise to a growing impulse toward humanitarianism and a

mood of sentimentality that produced greater empathy with the slave’s

plight.[9] Among the foremost literary efforts was William Cowper’s seven-

stanza poem The Negro’s Complaint, cited by Clarkson as an influential

popular work that spread throughout England “where it was sung as a

ballad; and where it gave a plain account of the subject, with an

appropriate feeling, to those who heard it.” [10]

Employing a combination of visual imagery and verse, nineteenth-century

British potters produced a variety of wares designed to arouse sympathy

for the slave. Many themes were evoked, including depictions of the

anguish of family separation and graphic portrayals of slavery’s horrors

(figs. 12, 13, 14, 15 and 16). Other ceramic pieces reveal a more subtle

approach to promoting the abolitionist cause. One strategy was to

incorporate the message into the familiar, traditional form of the rhyming

couplet commonly applied to English hollow ware (fig. 17). A popular verse

that has its origins in the eighteenth century but was employed on later

nineteenth-century earthenware proclaims:

British potters produced a variety of wares designed to arouse sympathy

for the slave. Many themes were evoked, including depictions of the

anguish of family separation and graphic portrayals of slavery’s horrors

(figs. 12, 13, 14, 15 and 16). Other ceramic pieces reveal a more subtle

approach to promoting the abolitionist cause. One strategy was to

incorporate the message into the familiar, traditional form of the rhyming

couplet commonly applied to English hollow ware (fig. 17). A popular verse

that has its origins in the eighteenth century but was employed on later

nineteenth-century earthenware proclaims:

Health to the Sick

Honour to the Brave

Success attend true Love

And Freedom to the Slave

Certain designs used by both British and other European potters not only

aroused sympathy for slaves but also goaded supporters of the abolitionist

cause to positive action. One option open to the average consumer was to

refuse to purchase goods produced by slaves. William Fox’s 1791

pamphlet, An Address to the People of Great Britain on the Propriety of

Abstaining from West India Sugar & Rum, apparently provided the impetus

for just such a campaign. [11] This early example of what came to be known

as a “boycott” in the late nineteenth century is manifest in the injunction

enameled on early nineteenth-century earthenware and bone china not to

buy West Indian sugar that had been brought to market through the

exploitation of slave labor (figs. 18, 19).

aroused sympathy for slaves but also goaded supporters of the abolitionist

cause to positive action. One option open to the average consumer was to

refuse to purchase goods produced by slaves. William Fox’s 1791

pamphlet, An Address to the People of Great Britain on the Propriety of

Abstaining from West India Sugar & Rum, apparently provided the impetus

for just such a campaign. [11] This early example of what came to be known

as a “boycott” in the late nineteenth century is manifest in the injunction

enameled on early nineteenth-century earthenware and bone china not to

buy West Indian sugar that had been brought to market through the

exploitation of slave labor (figs. 18, 19).

[1] The Selected Letters of Josiah

Wedgwood, edited by Anne Finer and

George Savage (London: Cory, Adams,

and Mackay, 1965), p. 311; Robin Reilly,

Josiah Wedgwood 1730–1795 (London:

Macmillan, 1992) p. 287.

Wedgwood, edited by Anne Finer and

George Savage (London: Cory, Adams,

and Mackay, 1965), p. 311; Robin Reilly,

Josiah Wedgwood 1730–1795 (London:

Macmillan, 1992) p. 287.

[2] Reilly, Wedgwood, p. 286.

Figure 1 Medallion, Josiah Wedgwood, Staffordshire, England,

ca. 1787. Jasperware. D. 1 1/8". (Chipstone Foundation; photo,

Gavin Ashworth.) Design of chained and kneeling slave in

profile taken from the seal of the Society for the Abolition of

the Slave Trade.

ca. 1787. Jasperware. D. 1 1/8". (Chipstone Foundation; photo,

Gavin Ashworth.) Design of chained and kneeling slave in

profile taken from the seal of the Society for the Abolition of

the Slave Trade.

[3] Thomas Clarkson, The History of the

Rise, Progress, and accomplishment of

the Abolition of the African Slave-Trade

by the British Parliament (1808; reprint,

London: Frank Cass & Co., 1968), p. 192.

Rise, Progress, and accomplishment of

the Abolition of the African Slave-Trade

by the British Parliament (1808; reprint,

London: Frank Cass & Co., 1968), p. 192.

[4] David Dabydeen, Hogarth’s Blacks:

Images of Blacks in Eighteenth-Century

English Art (Athens, Ga.: University of

Georgia Press, 1987), pp. 21–26. See

also Hugh Honour, The Image of the

Black in Western Art, vol. 4, From the

American Revolution to World War I,

part 1, Slaves and Liberators

(Cambridge: Harvard University Press,

1989).

Images of Blacks in Eighteenth-Century

English Art (Athens, Ga.: University of

Georgia Press, 1987), pp. 21–26. See

also Hugh Honour, The Image of the

Black in Western Art, vol. 4, From the

American Revolution to World War I,

part 1, Slaves and Liberators

(Cambridge: Harvard University Press,

1989).

[5] Dabydeen, Hogarth’s Blacks, p. 18.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ambrose Heal, The Signboards of Old

London Shops: A Review of the Shop

Signs employed by the London Tradesmen

during the XVIIth and XVIIIth Centuries

(New York: Benjamin Blom, Inc., 1972),

pp. 21–22. Jacob Larwood and John C.

Hotten, The History of Signboards, from

the Earliest Times to the Present Day, 6th

ed. (London: John C. Hotten, n.d.), p.

432. Preface dated June 1866.

London Shops: A Review of the Shop

Signs employed by the London Tradesmen

during the XVIIth and XVIIIth Centuries

(New York: Benjamin Blom, Inc., 1972),

pp. 21–22. Jacob Larwood and John C.

Hotten, The History of Signboards, from

the Earliest Times to the Present Day, 6th

ed. (London: John C. Hotten, n.d.), p.

432. Preface dated June 1866.

[8] Phillip Lapansky, “Graphic Discord:

Abolitionist and Antiabolitionist Images” in

The Abolitionist Sisterhood: Women’s

Political Culture in Antebellum America,

edited by Jean Fagan Yellin and John C.

Van Horne (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell

University Press, 1994), p. 216.

Abolitionist and Antiabolitionist Images” in

The Abolitionist Sisterhood: Women’s

Political Culture in Antebellum America,

edited by Jean Fagan Yellin and John C.

Van Horne (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell

University Press, 1994), p. 216.

[9] Winthrop D. Jordan, The White Man’s

Burden: Historical Origins of Racism in the

United States (New York: Oxford

University Press, 1982), pp. 142–43;

Betty Fladeland, Men and Brothers: Anglo-

American Antislavery Cooperation

(Urbana: University of Illinois Press,

1972), p. 13.

Burden: Historical Origins of Racism in the

United States (New York: Oxford

University Press, 1982), pp. 142–43;

Betty Fladeland, Men and Brothers: Anglo-

American Antislavery Cooperation

(Urbana: University of Illinois Press,

1972), p. 13.

[10] Clarkson, Abolition of the African

Slave-Trade, pp. 190–91.

Slave-Trade, pp. 190–91.

[11] William Fox, An Address to the

People; Correspondence of Josiah

Wedgwood 1781–1794 (Didsbury,

Manchester, Eng.: E. J. Morten Ltd,

1906), 3: 183.

People; Correspondence of Josiah

Wedgwood 1781–1794 (Didsbury,

Manchester, Eng.: E. J. Morten Ltd,

1906), 3: 183.

[12] Ibid., p. 183.

Figure 2 Medallion, Josiah Wedgwood, Staffordshire, England,

ca. 1787. Jasperware and silver. D. 1 7/8". (Collection of Rex

Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

ca. 1787. Jasperware and silver. D. 1 7/8". (Collection of Rex

Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Figure 3 Patch box, England, ca. 1800. Painted enamel on

metal. L. 1 3/4". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin

Ashworth.)

metal. L. 1 3/4". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin

Ashworth.)

Figure 4 Halfpenny token, 1668. Copper. D. 7/8". (Collection of the author; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Head of black youth representing the Black Boy Pub.

Figure 5 Figural group, Staffordshire England, ca. 1760. Creamware. H. 5 3/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Figure 6 Cream jug, Staffordshire or Yorkshire, England, 1780–1790. Creamware. H. 4 1/2". (Collection of the author; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This jug, part of a larger tea service, has twisted strap handles with molded sprigs terminals and a black transfer print of The Tea Party.

Figure 7 Jug, England, ca. 1800. Pearlware. H. 9 1/2". (Collection of the author; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Armorial crest featuring blackamoor bust in profile.

Figure 8 Detail of the crest illustrated in figure 7.

Figure 9 Soup plate, France, ca. 1810. Porcelain. D. 9 3/4". (Collection of the author; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Blackamoor head and legend “Asgre

Lan Diogel ei Pherchen.”

Figure 10 Detail of the soup plate illustrated in fig. 9. The Latin legend translates as “A pure conscience is a safeguard to its possessor.”

Figure 11 Detail of an engraving, from Thomas Clarkson’s History of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade, London, 1807. Influential figures such as Thomas Clarkson were given the responsibility of collecting information to support the abolition of the slave trade. This included interviewing 20,000 sailors and obtaining equipment used on the slave ships such as iron handcuffs, leg-shackles, thumb screws, instruments for forcing open slaves’ jaws, and branding irons. In 1787 he published his pamphlet, A Summary View of the Slave Trade and of the Probable Consequences of Its Abolition. After the abolishment of the British slave trade in 1807, Clarkson published his book History of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade.

Figure 12 Child’s mug, England, ca. 1840. Whiteware. H. 2 1/2". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This enamel-colored black transfer print depicts the capture of native Africans by European slavers, along with the opening verse from William Cowper’s The Negro’s Complaint: “Forcd from home and all its pleasures/Afric’s coast we left forlorn/To increase a stranger’s treasures/O’er the raging billows borne.”

Figure 13 Jug, Staffordshire or Sunderland, ca. 1820. Pearlware. H. 4 1/2". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo Gavin Ashworth.) This jug with copper and pink luster trim shows a transfer-printed variation of the Wedgwood plaque design. This one features a frontal view of a chained and seated slave, and verses from William Cowper’s The Negro’s Complaint on the other side. Note the reversal, most likely unintentional, of “I” and “Not” in the printed motto.

Figure 14 Detail of the reverse of the jug illustrated in fig. 13. This stanza from The Negro’s Complaint reads (italics mine): “Slaves of gold, whose sordid dealings/ Tarnish all your boasted powers,/Prove that you have human feelings/Ere you proudly question ours!”

Figure 15 Figural group, France or England, ca. 1820. Porcelain. H. 6 1/4". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) A late eighteenth-century antislavery pamphlet by William Fox included a section on punishment in which a Royal Navy admiral attested that the flogging of slaves was much more severe than that administered to sailors aboard English men-of-war. More explicitly, an English general asserted “there is no comparison between regimental flogging, which only cuts the skin, and the plantation, which cuts out the flesh.”

Figure 16 Reverse view of the figural group illustrated in fig. 15.

Figure 17 Mug, England, ca. 1850. Porcelain H. 3". (Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) In elaborate gold script: “Health to the Sick/ Honour to the Brave/Success attend true Love/ And Freedom to the Slave.”

Figure 18 Sugar bowl, England, 1820–1830. Bone china. H. 4 5/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) The decoration of the kneeling slave in the tropical environment is enameled over the glaze suggesting that it may have been produced for a special anti-slavery fair or occasion.

Figure 19 Reverse of the sugar bowl illustrated in fig. 18. Legend reads: “East India Sugar not made/By Slaves/By Six families using/East India, instead of/West India Sugar, one/Slave less is required.” The wording represents a somewhat sanitized version of Fox’s formulation that “A family that uses 5 lb. of sugar per week...will, by abstaining from the consumption 21 months, prevent the slavery or murder of one fellow creature” and tactfully omits the pamphleteer’s more gruesome analogy “that in every pound of sugar used...we may be considered as consuming two ounces of human flesh.”

Figure 4 Halfpenny token, 1668. Copper. D. 7/8". (Collection

of the author; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Head of black youth

representing the Black Boy Pub.

of the author; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Head of black youth

representing the Black Boy Pub.

Ceramics in America 2002

Show all Figures only

Contents

Notes:

• Sliding/scrolling colums left and right of article

colum for the foot notes and for the figures.

colum for the foot notes and for the figures.

• figs in text anchored to the images in left

column.

column.