C H I P S T O N E

Sam Margolin

“And Freedom to the Slave”: Antislavery Ceramics, 1787–1865

Ceramics in America, 2002

Figures

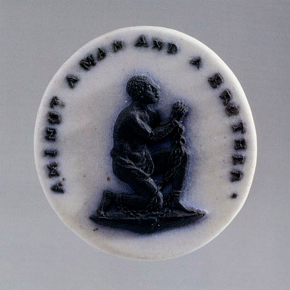

Figure 1 Medallion, Josiah Wedgwood,

Staffordshire, England, ca. 1787.

Jasperware. D. 1 1/8". (Chipstone

Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Design of chained and kneeling slave in

profile taken from the seal of the Society

for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

Staffordshire, England, ca. 1787.

Jasperware. D. 1 1/8". (Chipstone

Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Design of chained and kneeling slave in

profile taken from the seal of the Society

for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

Figure 2 Medallion, Josiah Wedgwood,

Staffordshire, England, ca. 1787.

Jasperware and silver. D. 1 7/8".

(Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin

Ashworth.)

Staffordshire, England, ca. 1787.

Jasperware and silver. D. 1 7/8".

(Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin

Ashworth.)

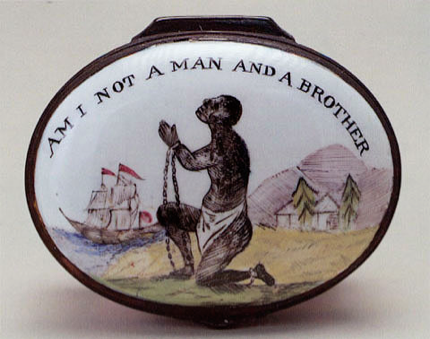

Figure 3 Patch box, England, ca. 1800. Painted

enamel on metal. L. 1 3/4". (Collection of Rex

Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

enamel on metal. L. 1 3/4". (Collection of Rex

Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Figure 4 Halfpenny token, 1668.

Copper. D. 7/8". (Collection of the

author; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Head

of black youth representing the Black

Boy Pub.

Copper. D. 7/8". (Collection of the

author; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Head

of black youth representing the Black

Boy Pub.

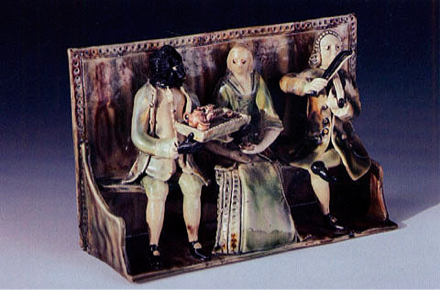

Figure 5 Figural group, Staffordshire England, ca. 1760.

Creamware. H. 5 3/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg

Foundation.)

Creamware. H. 5 3/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg

Foundation.)

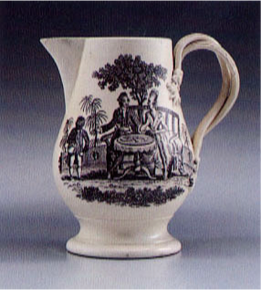

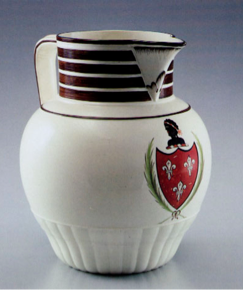

Figure 6 Cream jug, Staffordshire or

Yorkshire, England, 1780–1790.

Creamware. H. 4 1/2". (Collection of

the author; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

This jug, part of a larger tea service,

has twisted strap handles with

molded sprigs terminals and a black

transfer print of The Tea Party.

Yorkshire, England, 1780–1790.

Creamware. H. 4 1/2". (Collection of

the author; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

This jug, part of a larger tea service,

has twisted strap handles with

molded sprigs terminals and a black

transfer print of The Tea Party.

Figure 7 Jug, England, ca. 1800.

Pearlware. H. 9 1/2". (Collection

of the author; photo, Gavin

Ashworth.) Armorial crest

featuring blackamoor bust in

profile.

Pearlware. H. 9 1/2". (Collection

of the author; photo, Gavin

Ashworth.) Armorial crest

featuring blackamoor bust in

profile.

Figure 8 Detail of the crest illustrated

in figure 7.

in figure 7.

Figure 9 Soup plate, France, ca.

1810. Porcelain. D. 9 3/4". (Collection

of the author; photo, Gavin

Ashworth.) Blackamoor head and

legend “Asgre

1810. Porcelain. D. 9 3/4". (Collection

of the author; photo, Gavin

Ashworth.) Blackamoor head and

legend “Asgre

Lan Diogel ei Pherchen.”

Figure 10 Detail of the soup

plate illustrated in fig. 9. The

Latin legend translates as “A

pure conscience is a safeguard

to its possessor.”

plate illustrated in fig. 9. The

Latin legend translates as “A

pure conscience is a safeguard

to its possessor.”

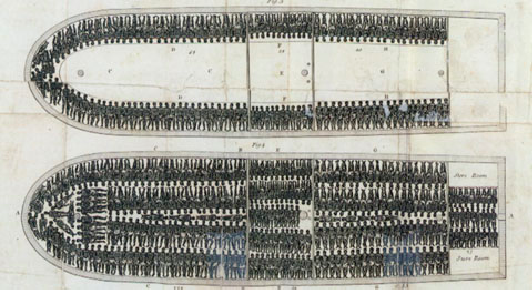

Figure 11 Detail of an engraving, from Thomas Clarkson’s History of the

Abolition of the African Slave Trade, London, 1807. Influential figures such

as Thomas Clarkson were given the responsibility of collecting information

to support the abolition of the slave trade. This included interviewing

20,000 sailors and obtaining equipment used on the slave ships such as

iron handcuffs, leg-shackles, thumb screws, instruments for forcing open

slaves’ jaws, and branding irons. In 1787 he published his pamphlet, A

Summary View of the Slave Trade and of the Probable Consequences of Its

Abolition. After the abolishment of the British slave trade in 1807, Clarkson

published his book History of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade.

Abolition of the African Slave Trade, London, 1807. Influential figures such

as Thomas Clarkson were given the responsibility of collecting information

to support the abolition of the slave trade. This included interviewing

20,000 sailors and obtaining equipment used on the slave ships such as

iron handcuffs, leg-shackles, thumb screws, instruments for forcing open

slaves’ jaws, and branding irons. In 1787 he published his pamphlet, A

Summary View of the Slave Trade and of the Probable Consequences of Its

Abolition. After the abolishment of the British slave trade in 1807, Clarkson

published his book History of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade.

Figure 12 Child’s mug, England, ca. 1840.

Whiteware. H. 2 1/2". (Collection of Rex

Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This

enamel-colored black transfer print

depicts the capture of native Africans by

European slavers, along with the opening

verse from William Cowper’s The Negro’s

Complaint: “Forcd from home and all its

pleasures/Afric’s coast we left forlorn/To

increase a stranger’s treasures/O’er the

raging billows borne.”

Whiteware. H. 2 1/2". (Collection of Rex

Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This

enamel-colored black transfer print

depicts the capture of native Africans by

European slavers, along with the opening

verse from William Cowper’s The Negro’s

Complaint: “Forcd from home and all its

pleasures/Afric’s coast we left forlorn/To

increase a stranger’s treasures/O’er the

raging billows borne.”

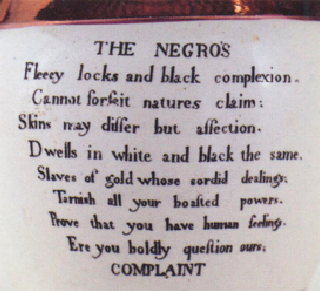

Figure 13 Jug, Staffordshire or Sunderland, ca.

1820. Pearlware. H. 4 1/2". (Collection of Rex

Stark; photo Gavin Ashworth.) This jug with

copper and pink luster trim shows a transfer-

printed variation of the Wedgwood plaque

design. This one features a frontal view of a

chained and seated slave, and verses from

William Cowper’s The Negro’s Complaint on the

other side. Note the reversal, most likely

unintentional, of “I” and “Not” in the printed

motto.

1820. Pearlware. H. 4 1/2". (Collection of Rex

Stark; photo Gavin Ashworth.) This jug with

copper and pink luster trim shows a transfer-

printed variation of the Wedgwood plaque

design. This one features a frontal view of a

chained and seated slave, and verses from

William Cowper’s The Negro’s Complaint on the

other side. Note the reversal, most likely

unintentional, of “I” and “Not” in the printed

motto.

Figure 14 Detail of the reverse of the jug

illustrated in fig. 13. This stanza from The

Negro’s Complaint reads (italics mine):

“Slaves of gold, whose sordid dealings/

Tarnish all your boasted powers,/Prove that

you have human feelings/Ere you proudly

question ours!”

illustrated in fig. 13. This stanza from The

Negro’s Complaint reads (italics mine):

“Slaves of gold, whose sordid dealings/

Tarnish all your boasted powers,/Prove that

you have human feelings/Ere you proudly

question ours!”

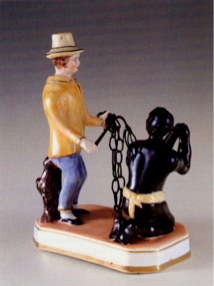

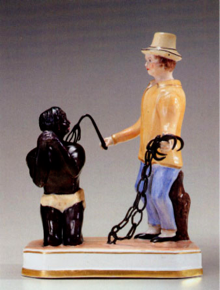

Figure 15 Figural group, France or

England, ca. 1820. Porcelain. H. 6 1/4".

(Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin

Ashworth.) A late eighteenth-century

antislavery pamphlet by William Fox

included a section on punishment in

which a Royal Navy admiral attested

that the flogging of slaves was much

more severe than that administered to

sailors aboard English men-of-war.

More explicitly, an English general

asserted “there is no comparison

between regimental flogging, which

only cuts the skin, and the plantation,

which cuts out the flesh.”

England, ca. 1820. Porcelain. H. 6 1/4".

(Collection of Rex Stark; photo, Gavin

Ashworth.) A late eighteenth-century

antislavery pamphlet by William Fox

included a section on punishment in

which a Royal Navy admiral attested

that the flogging of slaves was much

more severe than that administered to

sailors aboard English men-of-war.

More explicitly, an English general

asserted “there is no comparison

between regimental flogging, which

only cuts the skin, and the plantation,

which cuts out the flesh.”

Figure 16 Reverse view of the

figural group illustrated in fig.

15.

figural group illustrated in fig.

15.

Figure 17 Mug, England, ca. 1850.

Porcelain H. 3". (Collection of Rex Stark;

photo, Gavin Ashworth.) In elaborate gold

script: “Health to the Sick/ Honour to the

Brave/Success attend true Love/ And

Freedom to the Slave.”

Porcelain H. 3". (Collection of Rex Stark;

photo, Gavin Ashworth.) In elaborate gold

script: “Health to the Sick/ Honour to the

Brave/Success attend true Love/ And

Freedom to the Slave.”

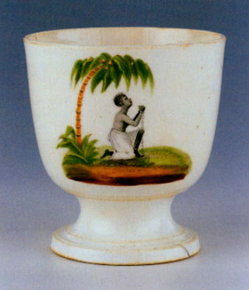

Figure 18 Sugar bowl, England,

1820–1830. Bone china. H. 4 5/8".

(Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg

Foundation.) The decoration of the

kneeling slave in the tropical

environment is enameled over the

glaze suggesting that it may have

been produced for a special anti-

slavery fair or occasion.

1820–1830. Bone china. H. 4 5/8".

(Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg

Foundation.) The decoration of the

kneeling slave in the tropical

environment is enameled over the

glaze suggesting that it may have

been produced for a special anti-

slavery fair or occasion.

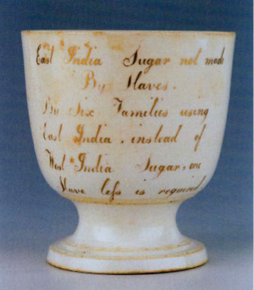

Figure 19 Reverse of the sugar

bowl illustrated in fig. 18. Legend

reads: “East India Sugar not

made/By Slaves/By Six families

using/East India, instead of/West

India Sugar, one/Slave less is

required.” The wording represents a

somewhat sanitized version of Fox’s

formulation that “A family that uses

5 lb. of sugar per week...will, by

abstaining from the consumption 21

months, prevent the slavery or

murder of one fellow creature” and

tactfully omits the pamphleteer’s

more gruesome analogy “that in

every pound of sugar used...we may

be considered as consuming two

ounces of human flesh.”

bowl illustrated in fig. 18. Legend

reads: “East India Sugar not

made/By Slaves/By Six families

using/East India, instead of/West

India Sugar, one/Slave less is

required.” The wording represents a

somewhat sanitized version of Fox’s

formulation that “A family that uses

5 lb. of sugar per week...will, by

abstaining from the consumption 21

months, prevent the slavery or

murder of one fellow creature” and

tactfully omits the pamphleteer’s

more gruesome analogy “that in

every pound of sugar used...we may

be considered as consuming two

ounces of human flesh.”

Notes:

• perhaps the captions should be

in scrolling boxes so this grid page

looks neater?

in scrolling boxes so this grid page

looks neater?

Ceramics in America 2002

Full article

Contents