Miniature portrait, Jabez Vodrey, ca. 1827. Oil on copper. (Courtesy, the Vodrey family; photo, Helga Studio.) Probably painted as a keepsake for his wife, before he set sail for America in 1827.

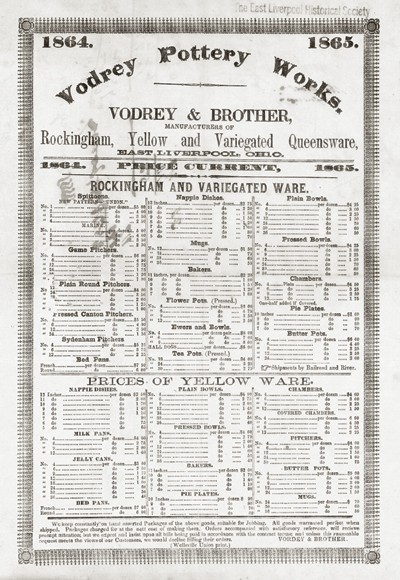

Price List, Vodrey Pottery Works, East Liverpool, Ohio, 1864–1865. (Courtesy, East Liverpool Historical Society.) The term Queen’s ware outlived any resemblance to the thin creamware perfected by Wedgwood and made by Jabez Vodrey in Louisville. As perpetuated by Vodrey’s sons, William H. and James N., and by other American potters, the term “yellow Queensware” had by the 1860s come to mean a high-fired stoneware of a deep straw color, made from the refractory clays found between coal seams. Collectors today know it as “yellowware.” The addition of a transparent brown coating (Rockingham glaze) or splashes of color (variegated) seems to have added twenty-five cents to the price of a dozen pressed bowls. The earliest record thus far found of Rockingham glaze being made in America is dated 1843.

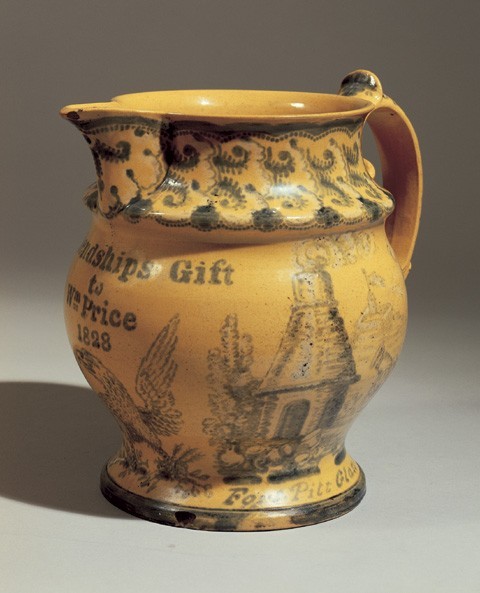

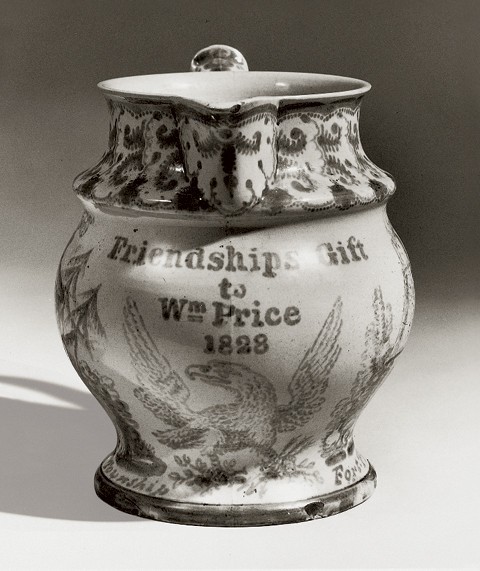

Pitcher, Frost & Vodrey, 1828. Yellow ware. H. 7". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania; photo, Helga Studio.) This pitcher was among the contents of a corner cupboard donated to the historical society in 1961 by Mrs. Frances W. Lane, a descendant of William Price, and was published many times as an example of midwestern manufacture. Not until the study of the Vodrey diary, however, did it become apparent that Frost & Vodrey must have been the potters who made it, and Sarah Vodrey, the decorator. Inscribed “Friendships Gift to Wm Price 1828,” its hand-painted scenes recall Price’s foundry, his round house, and his brief connection with the Fort Pitt Glass Works; an American eagle is emblazoned beneath his name under the spout.

Front view of pitcher illustrated in fig. 3.

Reverse view of pitcher illustrated in fig. 3.

Photocopy of a rabbit figure attributed to the Lewis Pottery. (Photos, courtesy of the authors unless otherwise noted.) A Louisville resident remembered seeing this small white pottery rabbit in the collection of the Filson Club. About 4" long, it was a size that potters would have called a “toy.” When the authors

visited the collection, only an old 8" x 10" glossy remained in the file, inscribed on the back: “Photo of bunny made in the Lewis Pottery during the years of the pottery’s existence 1829–1836. Given by Miss Mary Lee Warren, Louisville, Ky Oct. 1948.” When the collection was revisited, the photo, too, had disappeared, leaving only this poor photocopy of the original to prove that the bunny ever existed.

The rabbit appears to have been press molded, with incised details at mouth and eyes, and given an applied tail. Its ears were broken. While there were some examples of press-molding found in the dig, there was nothing quite like the rabbit. However, the Vodreys did later have a pet rabbit for the boys—“to teach them tenderness,” Jabez wrote.

Profile of plate illustrated in fig. 7. (Photo, Helga Studio.)

Oval plaque, Jabez and Sarah Vodrey, 1839. Whiteware. W. 5 5/8". (Courtesy, the Vodrey family; photo by Helga Studio.) A glazed white-bodied plaque, press molded with the standing figure of a man leaning on his horse, holding a riding crop in one hand. The patch of grass is painted underglaze in olive green; the incised “rope” edge is black. This type of figure is seen on many relief-molded Staffordshire pitchers, and may have appeared on Staffordshire-made plaques as well.

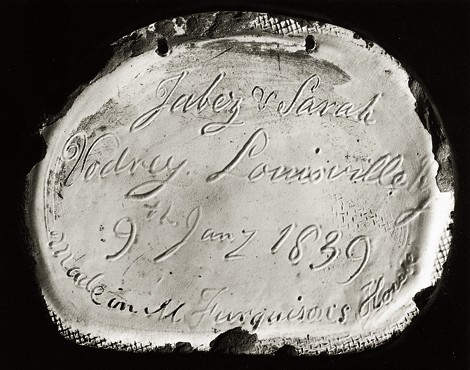

Reverse of plaque illustrated in fig. 9. Deeply incised on the back: “Jabez & Sarah/ Vodrey Louisville, Ky / 9th Jany 1839/ made in M Furguisons House.” Signed with the names of both Vodreys and dated only weeks before Jabez left Louisville to take over the management of the Troy Pottery, this plaque is the only irrefutable document of their work in Louisville.

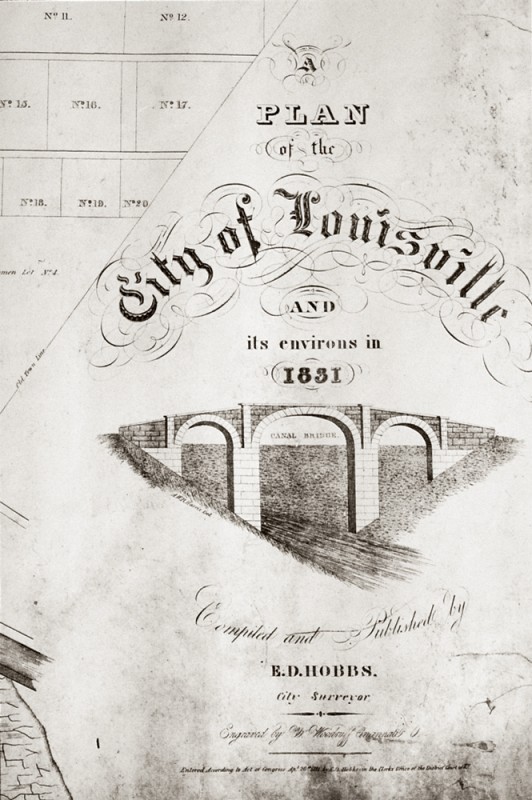

Title page from Plan of the City of Louisville And its environs in 1831. (Courtesy, Filson Club.)

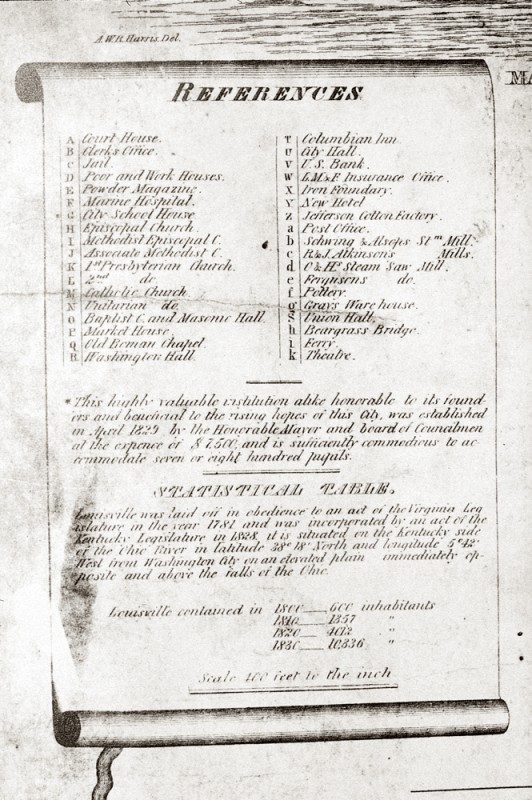

Location index to the Plan of the City of Louisville. The pottery is referenced as “f”. (Courtesy, Filson Club.)

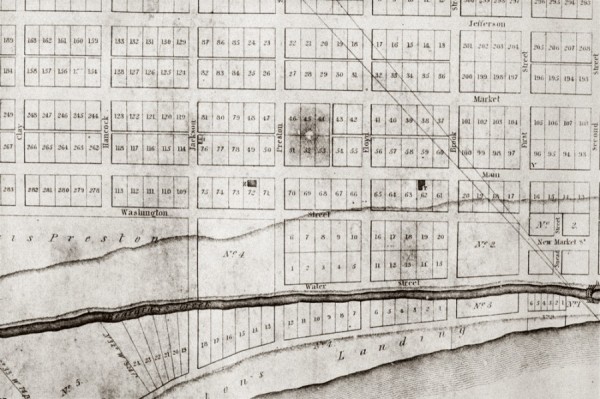

Detail of the Plan of the City of Louisville, showing the location of the pottery on Lot 76. (Courtesy, Filson Club.)

View of the Lewis Pottery site as an asphalt-covered parking lot.

Site Director Kim McBride guides the backhoe operator in clearing the asphalt and modern overburden, while archaeologist Jay Stottman (left) maps the trenches.

Archaeologist Bob Genheimer exposes remains of a kiln foundation.

Artifacts were carefully separated by hand from potters’ clays kept moist in the earth, too viscous to be sifted.

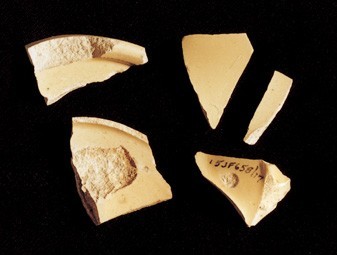

White-bodied, embossed-edge sherds, Lewis Pottery, 1829–1837. To be able to supply white plates, made from native materials, for the dinner tables of the nation was to an American fineware potter the pinnacle of success. And once Staffordshire potters began to export white-bodied ware shortly after the War of 1812, it became an imperative.

These four fragments of plate rims are certainly white bodied—despite the stains absorbed from being in the earth for 170 years—and proof that the Lewis Pottery did achieve that goal, unheralded though the company was. The details of the mold are sharp, and the rim design borrows liberally from the variety of embossed edges popular since the 1780s and still a favorite import in the 1820s and 1830s. They might well have been decorated with underglaze blue had they not been discarded. A two-line invoice for a small amount of calcined cobalt was copied into the Louisville pages of the diary:

Messrs. Lewis & Vodrey September 29th 1833

to 1/2 lb of Blue Calx $3.50

This seems outrageously expensive for such a small amount, but calx was a refined form of cobalt and such a potent coloring agent that it went far. Surprisingly, there was almost no evidence of blue decoration in what was found at the dig.

Plates, Staffordshire, 1820–1835. Pearlware. (Private collection; photo, Hans Lorenz.) Examples of embossed-edge plates trimmed in both blue and green made in Staffordshire and exported to the United States in huge quantities in the 1820s.

Rim sherds from London-shape “dipt” creamware bowls, Lewis Pottery, 1829–1837. One great challenge in ceramic archaeology is identifying the vessel forms; another, is accepting that this identification is never certain. When all the bits and pieces were washed, numbered, and recorded as to where they were found, they were sorted by glaze, color, texture, thickness—any visual means of grouping them. After these ceramic groups were transported to Cincinnati, Bob Genheimer’s corps of volunteers glued and assembled the hundreds of jigsaw puzzles. Then, aided by Vodrey’s own notes and accounts, by research into contemporary production here and abroad, by visualizing the invisible parts, by guess and by gosh, we reached conclusions—or we did not.

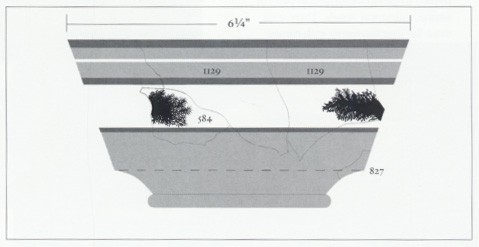

Sherds from cream-color bowls banded in brown and white, Lewis Pottery, 1829–1837. Twenty-five white-bodied sherds were glazed a cream color. They were from bowls of varying sizes and thicknesses and had differing sets of narrow brown and opaque white slip bands, each line 1/8" wide. The bowl above had a projected diameter of 8".

Projected drawing of bowl shape based on sherds illustrated in fig. 22. (Drawing by Diana Stradling.)

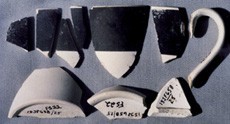

Cup, Lewis Pottery, 1829–1837. Cream-colored banded in brown and white. H. 1 3/4". Four large sherds, all apparently clear-glazed with very fine crazing, over a cream-colored body, assembled into an S-curved teacup, the flaring rim thinned at the edge. A small hole between the sherds indicates where a handle may have been attached. Decorated with bands of colored slip, the lower line of brown glaze has completely peeled away, perhaps because it was applied onto the tan slip and not directly onto the body. The shape of the cup, with a different handle, can be found among the early numbers—131 and 136—in the first pattern book of W. Ridgway & Co., a firm established early in 1831. Vodrey must have adapted the shapes he admired among the imported Ridgway designs he had seen at Mr. Kerr’s “house of splended ware from Allcocks, Ridgeways,” which he wrote about in 1836. The Kerrs later operated a “China Hall” in Philadelphia at the time of the Centennial in 1876, at 1218 Chestnut Street, and another in Ireland.

Sherds, Lewis Pottery, 1829–1837. Slip decorated in Common Cable pattern. A total of thirteen small sherds, all biscuit- and white-bodied, are in this group; one or two have marbleized slip and some are feathered at the edges.

Fragments of cylindrical mugs, or canns, Lewis Pottery, 1829–1837. H. 2 1/2". Nine white-bodied biscuit sherds seemed to group themselves as parts of similar, cylindrical vessels. There were three flat base fragments with turned footrims, wall fragments that were vertical when stood on their rims, and one molded handle. A wide band of brown slip had been applied to the walls, then had been shaved flat and smoothed, the turner’s tool leaving traces of horizontal scoring. The upper terminal of the white handle had brown slip adhering to it, and a corresponding lack of slip on a rim fragment revealed its probable location; a shallow flake out of a base was probably where the lower terminal had been attached. From these observations, an overall measurement of the vessel could be projected.

Mugs of a similar size and shape were designated “square chocolates” by Leeds and other English potteries. Vodrey’s odd choice of decoration—the broad band of brown slip on the white body—suggests that he may have had this function in mind for these cups.

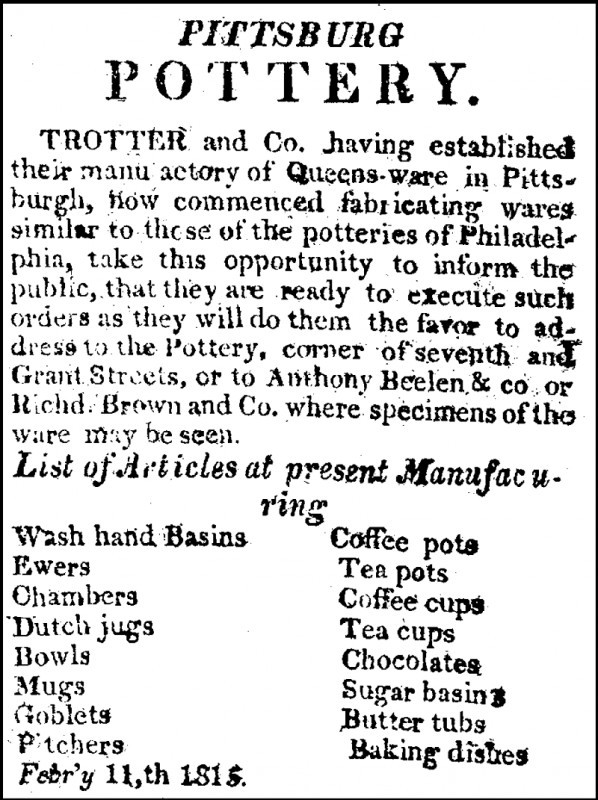

Newspaper advertisement for the Pittsburg Pottery, 11 February 1815. (Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.) Chocolates, mugs, and cups, but no saucers or plates, were being made by Alexander Trotter. An ambitious potter, he left Philadelphia to form his own company but his western venture succumbed to bad times after the end of the War of 1812. By 1819, he had moved again to try his luck in Baltimore.

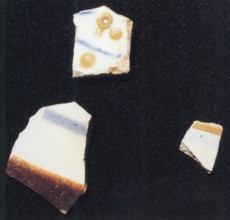

Sherds from unidentified vessels, Lewis Pottery, 1829–1837. Whiteware. The only traces of blue found on fragments at the Lewis Pottery site appeared on these tiny sherds. The dollop of yellow-green had a burst bubble in its center. Many had a smooth, opaque enamel-like surface.

Unglazed lid fragments, Lewis Pottery, 1829–1837. There were three intriguing sherds each with a layer of black clay embedded at the core. In one, the1/16" thickness was so consistent and precisely centered between cream-colored layers that it appeared to be a deliberately placed lamination. However, in the two assembled pieces shown above the black layer wobbles in thickness, and does not extend to the edge, or to the center of the lid, where an empty crater marks the spot where a finial had blown off during firing.

Opinions vary about the cause or intent—one expert suggesting that clays with different expansion rates might have been utilized to counteract a tendency to warp; another, that the black layer is the result of bloat caused by accidental conditions in the kiln.

The lid illustrated in figure 29 bears a strong resemblance to the family’s “cookie jar,” believed to have been made by Jabez at a somewhat later date, possibly in Troy. Interestingly, its large, flat lid was made without a finial.

Two similar, smaller jars in the East Liverpool Museum of Ceramics have been attributed to the East Liverpool pottery of Vodrey & Brother in the 1860s. These jars were also made without finials.

Sherds from salve jars, Lewis Pottery, 1829–1837. Five fragments that appear to be from ointment pots or jars of a yellowish enamel-type glaze. One retains an arc of a foot ring; another interior piece retains a bit of the vessel wall. A druggist named Peter Gardner was listed in the Louisville City Directory for the Year 1832 “at Mr. Lewis; s[outh] s[ide] Main b.[etween] Jackson and Preston.” This explains the finding of small round jar fragments found among the pottery wasters. Gardner probably had his pharmacy in the pottery store that was located on the side of the Lewis property. There were no subsequent directories until 1838, and he is not listed again.

Tobacco pipes, Lewis Pottery, circa 1815–1840s. Earthenware and stoneware. Tobacco pipes were everywhere on the lot. Some were complete, but most were in pieces; some were warped, and some all but melted; some were saltglazed stoneware, redware, even yellow ware—mementos of every potter who ever worked the site. All were the short, stubby shape typically found in American archaeology in date contexts through the late nineteenth century, the kind that were meant to have a stiff reed stem inserted into the stub.

Tobacco pipes, Lewis Pottery, 1829–1837. Whiteware. There were no white biscuit earthenware pipes and no long stems, broken or otherwise, of the sort still being imported from England. But there were, scattered throughout, white-bodied pipes with a longer bowl shape than all the others, which had an innovative ivory white glaze—smooth and opaque, like that found on some of the decorated sherds at the site—and these had to have been made by Vodrey. We know that by 1838 Vodrey was experimenting with marbled and painted pipes, the latter being decorated with underglaze color. In 1839 he was selling plain and marbled pipes at $1 per hundred, while painted pipes were at $1.50 per hundred. He had been making pipes since his arrival in Pittsburgh in 1827 and to him they were something of a bread-and-butter line. They were priced by the hundred but were often shipped by the barrel, as many as five thousand at a time. In constant demand, they represented a steady income to the potter.